Abstract

Research on the impact of changes in air pollutant concentrations during peak traffic hours on hospital admissions for respiratory diseases (RD) is limited. This study utilized a distributed lag nonlinear model (DLNM) to investigate this effect. Between 2014 and 2019, a total of 109,419 RD patients were hospitalized across seven hospitals in Lanzhou, China. Except for ozone (O3), fine particulate matter (PM2.5), inhalable particulate matter (PM10), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and carbon monoxide (CO), which increased by 10 µg/m3 (1 mg/m3 for CO), the relative risk (RR) values of hospitalization for RD were 1.0211 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.0090, 1.0333] (lag0-7), 1.0026 ( 95% CI 1.0010, 1.0043) (lag0), 1.0615 (95% CI 1.0355, 1.0882) (lag0-7), 1.0650 (95% CI 1.0478, 1.0824) (lag0-7) and 1.1229 (95% CI 1.0686, 1.1800) ( lag0-7), respectively. The stratified analyses revealed that air pollutants, except for O3, affected both males and females. PM2.5, PM10, NO2, and CO had a greater impact on individuals aged < 15 years, while SO2 had a more pronounced effect on those aged ≥ 65 years. The impact of air pollutants on RD hospitalizations was more significant during the cold season. It was recommended that people reduce short-term outdoor exposure during peak traffic hours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution refers to the release of harmful substances into the atmosphere, caused by human activities or natural processes1. When these pollutants are emitted in higher concentrations and for longer durations than the ability of air to purify itself, they cause changes in the composition and concentration of the atmosphere, leading to the formation of pollution. The effects of pollution resulting from human activities, especially industrial and vehicle emissions, are typically more widespread and severe than those caused by natural processes2. With the acceleration of industrialization and insufficient attention to environmental protection measures, incidents of air pollution have become more frequent, posing a serious threat to human health3.

Nearly 99% of the global population lives in areas where air quality does not meet the World Health Organization’s guidelines4. Air pollution has become a major public health issue and leads to significant economic losses worldwide. It contributes to a wide range of adverse health outcomes, including respiratory, cardiovascular, immune system, and metabolic diseases5,6.

Previous studies have primarily focused on the health effects of daily 24-hour average concentrations of air pollutants. However, in reality, air pollutant concentrations fluctuate and change throughout the day. Using daily average concentrations as indicators overlooks this variation and may result in biased interpretations of the actual health effects7. A significant association between air pollutants and adverse health outcomes exists, even at low average daily concentrations8. This could be due to hourly periods of exposure to high levels of contaminants9. Currently, several studies have examined the health effects of higher concentrations of air pollutants10,11. However, changes in peak hourly concentrations of air pollutants do not have detrimental effects on all diseases. A study found that while fluctuations in peak hourly PM2.5 concentrations were linked to increased mortality from ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, no harmful effects were observed on mortality from acute myocardial infarction in Guangzhou, China12. Additionally, outdoor activities like commuting and exercising lead to increased exposure to air pollutants13. It could lead to adverse health effects.

Numerous studies have examined the effects of changes in daily average concentrations of air pollutants on RD. However, research focusing on the impact of air pollution during peak traffic hours on RD remains scarce. The aim of this study was to explore the effects of changes in air pollutant concentrations during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalizations.

Results

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of RD hospitalizations, air pollution during peak traffic hours, and meteorological factors from 2014 to 2019. A total of 109,419 RD-related hospitalizations were recorded, with an average of 49.94 hospitalizations per day. Among these, 64,403 were male and 45,016 were female. The number of individuals in the age groups < 15, 15–64, and ≥ 65 years were 34,034, 40,843, and 34,542, respectively. The average concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, and O3 during peak traffic hours were 45.05, 110.44, 19.39, 41.50, and 48.86 µg/m2, respectively. The average CO concentration was 1.19 mg/m2. The average daily temperature was 11.34 °C, and the average relative humidity was 51.03%.

Figure 1 illustrate the changes in RD admissions and concentrations of the six air pollutants during peak traffic hours from 2014 to 2019 in Lanzhou, China. The hospital admission volume of RD shows an overall increasing trend during the research period. The concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 show minimal changes, with only a brief peak during the summer. SO2 and CO concentrations are higher in winter and spring, and lower in summer and autumn. NO2 concentrations remained relatively stable from 2014 to 2017, with a pattern of higher levels in winter and spring and lower levels in summer and autumn from 2017 to 2019. O3 concentrations were relatively stable from 2014 to 2017, but exhibited higher levels in summer and autumn and lower levels in winter and spring from 2017 to 2019.

Table S1 presents the Spearman correlations between air pollution during peak traffic hours and the major meteorological factors. PM2.5 and PM10, as well as SO2 and CO, show strong positive correlations with each other. O3 is negatively correlated with all other air pollutants. The remaining air pollutants exhibit low positive correlations with each other. Temperature shows a low positive correlation with O3 and a low negative correlation with all other air pollutants. Relative humidity has a low negative correlation with all air pollutants, and temperature and relative humidity are also weakly negatively correlated.

Table 2 illustrates the impact of each 10 µg/m2 (1 mg/m2 for CO) increase in air pollutant concentration during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalization. PM2.5 showed harmful effects at lag0, lag0-2 ~ lag0-7, with the maximum effect occurring at lag0-7 (RR = 1.0211, 95% CI 1.0090, 1.0333). PM10 had a harmful effect at lag0 (RR = 1.0026, 95% CI 1.0010, 1.0034). SO2 exhibited harmful effects at lag6 ~ lag7 and lag0-4 ~ lag0-7, with the largest effect observed at lag0-7 (RR = 1.0615, 95% CI 1.0355, 1.0882). NO2 had harmful effects at lag0, lag3, lag6, and lag0-1 ~ lag0-7, with the most significant effect occurring at lag0-7 (RR = 1.0650, 95% CI 1.0478, 1.0824). CO showed harmful effects at lag6 ~ lag7 and lag0-1 ~ lag0-7, with the largest effect appearing at lag0-7 (RR = 1.1229, 95% CI 1.0686, 1.1800). No harmful effects of O3 on RD hospitalization were observed in this study.

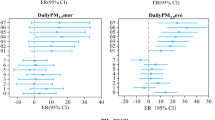

Figure 2 illustrates the exposure-response (E-R) curves for the concentrations of six air pollutants during peak traffic hours in relation to RD hospitalizations. Except for PM10 and O3, the effects of PM2.5, SO2, NO2, and CO on RD hospitalizations were generally linear. As the concentration of air pollutants increased, the risk of RD hospitalization rose steadily, with no evident threshold.

Table S2 presents the effects of each 10 µg/m2 (1 mg/m2 for CO) increase in air pollutant concentration during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalization by gender. PM2.5 had adverse effects on both males and females at lag0, lag0-3 ~ lag0-7, and lag0-2 ~ lag0-7, with the maximum effect observed at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.0213 (95% CI 1.0087, 1.0340) for males and 1.0207 (95% CI 1.0071, 1.0345) for females. PM10 showed harmful effects at lag0 for both genders, with RR values of 1.0029 (95% CI 1.0012, 1.0047) for males and 1.0023 (95% CI 1.0003, 1.0042) for females. SO2 negatively impacted both genders at lag6, lag0-5 ~ lag0-7, and lag6 ~ lag7, lag0-2 ~ lag0-7, with maximum effects at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.0535 (95% CI 1.0265, 1.0813) for males and 1.0728 (95% CI 1.0432, 1.1032) for females. NO2 had harmful effects at lag0, lag6, lag0-1 ~ lag0-7, and lag0, lag2, lag6 ~ lag7, lag0-1 ~ lag0-7, with the largest effects at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.0608 (95% CI 1.0429, 1.0790) for males and 1.0707 (95% CI 1.0513, 1.0905) for females. CO also showed detrimental effects at lag6, lag0-1 ~ lag0-7, and lag6 ~ lag7, lag0-2 ~ lag0-7, with maximum effects at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.1181 (95% CI 1.0617, 1.1776) for males and 1.1297 (95% CI 1.0682, 1.1947) for females. No harmful effects of O3 were observed in either gender.

Table S3 presents the effects of each 10 µg/m2 (1 mg/m2 for CO) increase in air pollutant concentration during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalization across age groups. PM2.5 had harmful effects on individuals aged < 15 and ≥ 65 years at lag0, lag3 –lag6, lag0-1–lag0-7, and lag7, lag0-3–lag0-7, respectively, with maximum effects at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.0490 (95% CI 1.0317, 1.0665) for individuals aged < 15 years and 1.0243 (95% CI 1.0096, 1.0394) for individuals aged ≥ 65 years. PM10 negatively affected individuals aged < 15, 15–64, and ≥ 65 years at lag0, lag0-1 ~ lag0-7, and lag0, respectively, with RR values of 1.0065 (95% CI 1.0026, 1.0104) for < 15 years, 1.0025 (95% CI 1.0002, 1.0048) for 15–64 years, and 1.0029 (95% CI 1.0008, 1.0050) for ≥ 65 years. SO2 showed harmful effects on individuals aged < 15 and ≥ 65 years at lag1, lag6, lag0-5 –lag0-7, and lag6, lag7, lag0-4–lag0-7, with maximum effects at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.0613 (95% CI 1.0251, 1.0987) for < 15 years and 1.0816 (95% CI 1.0495, 1.1146) for individuals aged ≥ 65 years. NO2 had harmful effects on individuals aged < 15, 15–64, and ≥ 65 years at lag0, lag3, lag6, lag0-1 ~ lag0-7, and lag0-1 ~ lag0-7 and lag6, lag0-1 –lag0-7, respectively, with maximum effects at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.0723 (95% CI 1.0489, 1.0961) for individuals aged < 15 years, 1.0445 (95% CI 1.0216, 1.0679) for 15–64 years, and 1.0570 (95% CI 1.0361, 1.0784) for individuals aged ≥ 65 years. CO had negative effects on individuals aged < 15 and ≥ 65 years at lag4 –lag6, lag0-2–lag0-7, and lag6 –lag7, lag0-3–lag0-7, with maximum effects at lag0-7. The RR values were 1.2051 (95% CI 1.1260, 1.2897) for < 15 years and 1.1430 (95% CI 1.0761, 1.2141) for individuals aged ≥ 65 years. No harmful effects of O3 on RD hospitalization across age groups were observed in this study.

Table S4 illustrates the impact of each 10 µg/m2 (1 mg/m2 for CO) increase in air pollutant concentration during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalization across different seasons. PM2.5, SO2, NO2, and CO showed harmful effects only during the cold season. The RR values were 1.0125 (95% CI 1.0000, 1.0252) for lag0-2, 1.0902 (95% CI 1.0553, 1.1262) for lag0-7, 1.0478 (95% CI 1.0277, 1.0683) for lag0-4, and 1.1997 (95% CI 1.1259, 1.2784) for lag0-7. PM10 had harmful effects in both warm and cold seasons at lag0, with RR values of 1.0030 (95% CI 1.0007, 1.0054) and 1.0024 (95% CI 1.0000, 1.0049), respectively. No detrimental effects of O3 were observed in either warm or cold seasons.

Table S5 presents the results of the two-pollutant model. Since PM2.5 and PM10 (r = 0.83), as well as CO and SO2 (r = 0.78), were highly correlated, both pairs were excluded from the two-pollutant model. For PM2.5, SO2, and CO, the introduction of additional pollutants reduced the harmful effects on RD hospitalization. In contrast, for PM10, NO2, and O3, the harmful effects remained largely unchanged. Table S6 presents the results of varying the degrees of freedom for the time variable. No significant changes were observed in the effect of air pollutant concentration changes during peak traffic hours on RD admissions, indicating that the model and results are reliable.

Discussion

The study employed DLNM to examine the short-term effects of changes in air pollutant concentrations during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalization in Lanzhou, China. After adjusting for meteorological factors, PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, and CO during peak traffic hours all had a detrimental effect on RD hospitalization, with the exception of O3. The sensitivity to air pollutants during peak traffic hours varied by gender and age.

Currently, the mechanisms related to the effects of air pollutants on RD are not well defined. The dominant potential mechanisms are oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and phagocyte dysfunction14. PM2.5 increases lung oxidants, like malondialdehyde, while decreasing antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase, resulting in cellular damage in the lungs15. Additionally, PM2.5 exposure elevates inflammation biomarkers like Th1 and Th17 cytokines, further exacerbating systemic inflammation16,17. NO2 can enter the bronchioles and alveoli, leading to myxedema and impairing small airway function18. Air pollutants reduce the ability to recognize pathogens by regulating phagocyte receptor expression, impair phagocyte motility and phagocytosis, and increase cytokine and chemokine production19.

Numerous studies have highlighted the impact of air pollutant concentration changes on RD hospitalization. However, most have focused on daily average pollutant concentrations and found a positive association between higher concentrations and increased RD hospitalization risk20,21,22. This study focuses on the correlation between changes in air pollutant concentrations during peak traffic hours and RD hospitalization. Previous studies have also explored the impact of peak hourly pollutant concentration changes on health. Peak hourly concentration refers to the highest hourly concentration in a 24-hour period, serving as an indicator of daily population exposure. For instance, peak hourly concentrations of PM2.5 affect hypertension clinics, children’s lower respiratory tract infection clinics, and hospitalization rates23,24,25. These studies have shown that hourly peak concentrations of air pollutants can serve as a proxy for daily average concentrations. One study using peak traffic hour concentrations as a measure of population exposure found a significant risk of hospitalization for stroke in hypertensive patients in Beijing, China11. The study also considered the effects of air pollution during peak traffic hours and outdoor activities during that time. Our results showed that PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, and CO during peak traffic hours have harmful effects on RD hospitalization, except for O3. This aligns with previous studies on daily mean concentrations26. Whereas, our previous study results showed that the daily mean concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2 and CO were 48.97 µg/m3, 114.85 µg/m3, 21.14 µg/m3, 47.33 µg/m3 and 1.24 mg/m3, respectively, and the maximum eight-hourly O3 concentration was 88.24 µg/m3 over the same study time range for the same area27. This may indicate that peak traffic concentrations of air pollutants play a driving role in health effects. This also suggests that air pollutant concentrations during peak traffic hours can serve as a proxy for daily average concentrations, enabling a more comprehensive exploration of the health effects of air pollution from multiple perspectives.

However, a previous study on the effect of changes in average daily air pollution concentrations on RD hospitalization found that SO2 was not associated with the risk of RD hospitalization, whereas PM10 was linked to an increased risk of RD hospitalization in Lanzhou, China28. One source of airborne SO2 is vehicle exhaust emissions. Our study focused on the health effects of air pollutants during peak traffic hours, considering the increased exposure to the population during these times and their contribution to air pollutant concentrations. The present study further observed the adverse effects of SO2. This may suggest that changes in average daily concentrations may mask the potential adverse effects of some air pollutants. In contrast, changes in peak traffic air pollutant concentrations provide a more nuanced picture of exposure risk. Additionally, the health effects of PM10 on populations have been shown to be intermittent throughout the day29. Since our study focused only on the health hazards of air pollutants during peak traffic hours, this may explain why the harmful effects of PM10 on RD hospitalization were not observed as significant.

This study found a negative association between changes in O3 concentrations during peak traffic hours and the relative risk of RD hospitalization. The results regarding the impact of O3 on RD hospitalization are currently inconsistent30,31,32. Variations in the composition and concentration of air pollution, as well as local living conditions across different regions, may contribute to differences in the health effects of O3 33,34. Additionally, demographic factors (e.g., age and health status) may lead to varying responses to the health effects of O3, thereby influencing hospitalization risks35. However, the precise mechanisms underlying these effects require further investigation.

In this study, E-R curves for air pollutants during peak traffic hours and RD hospitalizations were plotted. These curves have important public health implications, as changes in effect estimates can help detect the harmful effects of air pollution on RD hospitalization. The curves for PM2.5, SO2, NO2, and CO were nonlinear and showed no thresholds. Therefore, local governments should implement strict measures to control pollutant emissions and protect residents’ health.

This study also found that different air pollutants have varying effects on RD hospitalization by gender, a finding consistent with previous studies36,37. This may be attributed to differences in physiological characteristics and lifestyle habits between men and women. Additionally, significant regional variations in air pollutant characteristics could explain the inconsistent findings. Age stratification in this study revealed that individuals < 15 years and ≥ 65 years are more susceptible. This is likely because children are still developing and have incomplete immune functions, while the elderly have more fragile health, making both groups vulnerable to harmful environmental factors. NO2 also has harmful effects on people aged 15–64 years. As one of the main sources of NO2 is vehicle emissions, the pollutant concentrations during peak traffic hours were used as a proxy for population exposure, with NO2 being particularly relevant to young people, such as commuters.

Overall, air pollutants during peak traffic hours have a stronger harmful effect in the cold season, which is consistent with previous findings on the seasonal impact of daily mean air pollutant concentrations on RD hospitalization28,37. During the cold season, reduced physical activity and limited ventilation may weaken immunity and increase susceptibility to respiratory diseases, thereby raising hospitalization risks. Additionally, the dry climate facilitates the spread of respiratory viruses, further elevating the likelihood of hospital admissions38. Additionally, the cold season coincides with the heating period in Lanzhou, China. The combustion of fossil fuels results in excessive air pollutant emissions, while the local climate and geographical conditions hinder pollutant dispersion. These factors collectively increase population exposure to pollutants.

The study explored the impact of air pollutant concentration changes during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalizations, considering factors such as commuting and outdoor exercise. This offers a novel perspective on assessing the health effects of air pollution. However, the study has several limitations. Firstly, like previous related research, it is an ecological study that uses pollutant concentrations from environmental monitoring stations as proxies for human exposure. This approach may underestimate actual exposure levels, potentially deviating from real-world conditions. Secondly, the study relied solely on inpatient records from seven large general hospitals in the region. Despite the substantial sample size, it did not encompass all patient data, limiting its representativeness. Additionally, the study was conducted in a single city, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the analysis focused on respiratory diseases as a broad category without further subdivision into specific conditions, such as upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Conclusion

This study examined the impact of peak traffic hours on population exposure and air pollution levels. The results revealed that PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, and CO negatively affect RD hospitalizations. Authorities should consider implementing traffic restrictions during peak hours to mitigate air pollution. Future research should further investigate the effects of traffic management on air quality and public health. Additionally, regional studies incorporating meteorological and geographic factors are recommended to provide a more comprehensive understanding of pollutant exposure.

Methods

Study area

Lanzhou (E 102° 36′–104° 35′, N 35° 34′–37° 00′), the capital of Gansu Province, China, is a significant industrial base, transportation hub, and a key city along the overland Silk Road Economic Belt. With a long history of industrial development, it specializes in petrochemicals, metallurgy, and machinery manufacturing. The city is nestled among mountains, with its urban area spread along both sides of the Yellow River, making it a typical river valley city. It features a temperate continental monsoon climate characterized by scarce precipitation, abundant sunshine, high evaporation, dry conditions, low wind speeds, and frequent static wind phenomena.

Inpatient data

Based on the healthcare infrastructure and geographic characteristics of Lanzhou, China, we selected seven large general hospitals to gather daily inpatient data for RD from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2019. These hospitals were chosen for their advanced medical equipment, high-quality services, and well-established electronic medical record systems. Additionally, Lanzhou’s unique topography—spanning approximately 40 km east to west but only 3–8 km north to south—further justified the selection, as these hospitals are strategically distributed to cover the population effectively39. Residential areas are concentrated along both sides of the Yellow River, with a west-to-east distribution. This ensures that the city’s densely populated areas are within a 15-kilometre radius of the seven hospitals40. These hospitals offer convenient medical services to local residents, making the hospitalization data collected in this study a reliable representation of respiratory disease hospitalizations in Lanzhou, China. The data includes gender, age, home address, admission time, hospital diagnosis, and International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes for the cases, focusing on respiratory diseases (ICD-10: J00-J99). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the hospitalization data were collected without identifiable personal information. Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the absence of identifiable participant information, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Lanzhou University School of Public Health waived ethical approval and informed consent. All research methods adhered to the guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. First, patients with missing information on age, gender, or home address were excluded. Second, data from patients whose residence was outside the four districts of central Lanzhou were removed. Finally, to avoid double-counting, only the first visit for patients with multiple visits during the study period was considered, as multiple visits could be due to follow-ups, transfers, or referrals.

Air pollutant data

Hourly air pollutant data from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2019 were collected from four air quality monitoring stations (Fig. 3) in the main urban area of Lanzhou, China. The pollutants include fine particulate matter (PM2.5), inhalable particulate matter (PM10), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), and ozone (O3). The monitoring methods for air pollutant concentrations followed national ambient air quality sampling standards, with professional personnel verifying and inspecting the data to ensure its accuracy and reliability. Peak traffic hours typically occur from 7:00 to 10:00 in the morning and from 16:00 to 19:00 in the evening. Considering residents’ morning and evening exercise routines and commuters’ walking patterns, we adjusted the peak traffic hours to 6:00 to 10:00 in the morning and 16:00 to 20:00 in the evening. We calculated the average air pollutant concentration during peak traffic hours for each day from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2019, using the concentration value as the population’s exposure for that day.

The location of four air quality monitoring stations in Lanzhou49.

Meteorological data

The data of daily meteorological information was obtained from China Meteorological Data Service Centre (http://data.cma.cn/) from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2019 in Lanzhou, China, which mainly includes the daily average temperature (MT) (°C) and Mean Relative Humidity (RH) (%). These meteorological data were collected and processed in accordance with the specification requirements for surface meteorological observations of the China Meteorological Administration (CMA), and the data were complete, valid and of good quality, with no missing values in the observations during the study period.

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses of daily hospital admissions for RD, peak concentrations of air pollutants, and meteorological factors. Statistical indicators included mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum (Min), percentiles (25th, 50th, 75th), and maximum (Max). We also plotted time series of RD admissions and peak pollutant concentrations to illustrate their trends. The Spearman’s rank correlation method was used to analyze the relationship between air pollutants and meteorological factors during peak traffic hours, with the correlation coefficient calculated at a significance level of α = 0.05.

The detrimental effects of air pollutants on RD hospitalizations are persistent and delayed. The DLNM was used to explore the relationship between air pollution and RD hospitalizations41. Previous studies have shown that the daily distribution follows a quasi-Poisson distribution, as RD hospitalizations are rare events38. To avoid over-discretization, a quasi-Poisson connection function was used. Each pollutant was modeled separately, with the effects of day of the week (DOW) and holidays controlled using categorical variables. A DLNM was then constructed to estimate the relationship between changes in air pollution concentrations during peak traffic hours and RD hospitalizations, combining a generalized additive model (GAM) with a quasi-Poisson distribution. The model used in this study is as follows:

where, t is the observation day. Yt is the dependent variable, indicating the number of RD admissions on day t. E(Yt) is the anticipated value of RD admission on that date. α is the intercept. \(\:\beta\:{X}_{t,l}\)is a cross-base function of the air pollution. Time is the time variable. \(\:MT\) is the temperature. \(\:RH\) is relative humidity. \(\:lag\) is the number of lag days. \(\:df\) is the degrees of freedom. \(\:ns\) is the natural cubic spline function. \(\:as.factor\left(\:\right)\) is the function used to control the categorical variables. \(\:Dow\) is a multicategorical variable representing the day of the week effect. \(\:Holiday\) is a binary categorical variable to represent the holiday effect.

Based on previous related studies and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), we determined the model parameters and degrees of freedom42,43,44,45. In the model, the cross-basis function for air pollutants was chosen to be linear with 3 df, while the cross-basis function for lag time was chosen to be polynomial with 4 df. The natural cubic spline function was used to control for long term trends and seasonality of the time variables with 7 df. Based on previous studies, the natural cubic spline function was also used to control for temperature and relative humidity with 3 df for each term34,46.

Previous studies have shown that air pollution has a lag effect on RD, which lasts no longer than seven days47,48. Therefore, the maximum lag for air pollutants was set at seven days in this study. The short-term impact of air pollutants during peak traffic hours on RD hospitalization was estimated using two models: single-day lag (lag0–lag7) and multi-day cumulative lag (lag0-1–lag0-7). Lag0 represents the effect of exposure on the same day, while lag1 reflects the effect of exposure on the previous day, and so on. Lag0-1 indicates the cumulative effect from the same day to the previous day, and so on. To examine the effect of air pollution on RD hospitalization across different populations and seasons, we stratified the study into subgroups based on gender (male and female), age (< 15 years, 15–64 years, ≥ 65 years), and seasons (May to October for the warm season, and November to April for the cold season). Subgroup analyses helped identify sensitive populations.

We then further assessed the significant differences between the effect estimates of the stratified analyses by calculating 95% CIs using the following equation:

where \(\:{\widehat{\text{Q}}}_{1}\) and \(\:{\widehat{\text{Q}}}_{2}\) indicate the estimates for two subgroups (e.g., male and female), \(\:\text{S}{\widehat{\text{E}}}_{1}\) and \(\:\text{S}{\widehat{\text{E}}}_{2}\) are their appropriate standard errors.

Additionally, based on the original single-pollutant model, we developed a two-pollutant model by including another air pollutant and controlling for it using a cubic spline function. According to the Spearman correlation results, two highly correlated air pollutants (r > 0.7) were not included in the same two-pollutant model to avoid the influence of strong covariance between variables on the results. To test the stability of the model, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the degrees of freedom of the time variable (df = 6, 7, 8, 9).

In this study, the effect estimates of changes in air pollutant concentrations during peak hours on RD hospitalizations were expressed as the RR and CI for every 10 µg/m2 (1 mg/m2 for CO) increase in RD concentration. All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.2 software.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the authors did not have permissions to share data but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sakti, A. D. et al. Multi-air pollution risk assessment in Southeast Asia region using integrated remote sensing and socio-economic data products. Sci. Total. Environ. 854, 158825 (2023).

Saleh, W. M., Ahmad, M. I., Yahya, E. B. & HPS, A. Nanostructured bioaerogels as a potential solution for particulate matter pollution. Gels (Basel, Switzerland) 9, 575 (2023).

Ren, Y., Yu, J., Zhang, G., Zhang, C. & Liao, W. The short- and long-run impacts of air pollution on human health: New evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 2385 (2023).

Bai, L., Wang, K., Liu, D. & Wu, S. Potential early effect biomarkers for ambient air pollution related mental disorders. Toxics 12, 454 (2024).

Glencross, D. A., Ho, T. R., Camiña, N., Hawrylowicz, C. M. & Pfeffer, P. E. Air pollution and its effects on the immune system. Free Radical Biol. Med. 151, 56–68 (2020).

Dominski, F. H. et al. Effects of air pollution on health: A mapping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Environ. Res. 201, 111487 (2021).

Lin, H. et al. Daily exceedance concentration hours: A novel indicator to measure acute cardiovascular effects of PM(2.5) in six Chinese subtropical cities. Environ. Int. 111, 117–123 (2018).

Calderón-Garcidueñas, L. et al. White matter hyperintensities, systemic inflammation, brain growth, and cognitive functions in children exposed to air pollution. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 31, 183–191 (2012).

da Silva, I., de Almeida, D. S., Hashimoto, E. M. & Martins, L. D. Risk assessment of temperature and air pollutants on hospitalizations for mental and behavioral disorders in Curitiba, Brazil. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 19, 79 (2020).

Moreno, T., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Viana, M. & Gibbons, W. Profiling transient daytime peaks in urban air pollutants: City centre traffic hotspot versus urban background concentrations. J. Environ. Monit. JEM 11, 1535–1542 (2009).

Zhao, Z. et al. Acute effect of air pollutants’ peak-hour concentrations on ischemic stroke hospital admissions among hypertension patients in Beijing, China, from 2014 to 2018. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 29, 41617–41627 (2022).

Lin, H. et al. Hourly peak PM(2.5) concentration associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in Guangzhou, China. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 27, 333–338 (2017).

Tainio, M. et al. Can air pollution negate the health benefits of cycling and walking?. Prev. Med. 87, 233–236 (2016).

Wang, Q. & Liu, S. The effects and pathogenesis of PM2.5 and its components on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 18, 493–506 (2023).

Ren, H. et al. Exposure to fine particulate matter induces self-recovery and susceptibility of oxidative stress and inflammation in rat lungs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 40262–40276 (2020).

Grilli, A. et al. Transcriptional profiling of human bronchial epithelial cell BEAS-2B exposed to diesel and biomass ultrafine particles. BMC Genomics 19, 302 (2018).

Gao, N. et al. Lung function and systemic inflammation associated with short-term air pollution exposure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in Beijing, China. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 19, 12 (2020).

Zhu, X. et al. Respiratory effects of traffic-related air pollution: A randomized, crossover analysis of lung function, airway metabolome, and biomarkers of airway injury. Environ. Health Perspect. 131, 57002 (2023).

Monoson, A. et al. Air pollution and respiratory infections: The past, present, and future. Toxicol. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 192, 3–14 (2023).

Wu, Z. et al. The lag-effects of meteorological factors and air pollutants on child respiratory diseases in Fuzhou, China. J. Glob. Health 12, 11010 (2022).

Lei, J. et al. Fine and coarse particulate air pollution and hospital admissions for a wide range of respiratory diseases: A nationwide case-crossover study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 52, 715–726 (2023).

Shin, H. H. et al. Sex-difference in air pollution-related acute circulatory and respiratory mortality and hospitalization. Sci. Total. Environ. 806, 150515 (2022).

Lin, X., Du, Z., Liu, Y. & Hao, Y. The short-term association of ambient fine particulate air pollution with hypertension clinic visits: A multi-community study in Guangzhou, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 774, 145707 (2021).

Liang, Z. et al. Three exposure metrics of size-specific particulate matter associated with acute lower respiratory infection hospitalization in children: A multi-city time-series analysis in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 816, 151636 (2022).

Xiao, D. et al. Three exposure metrics for fine particulate matter associated with outpatient visits for acute lower respiratory infection among children in Guangzhou, China. Front. Public Health 10, 876496 (2022).

Luo, L. et al. Short-term effects of ambient air pollution on hospitalization for respiratory disease in Taiyuan, China: A time-series analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 2160 (2018).

Zhang, W., Ruan, Y. & Ling, J. Short-term effects of NO(2) exposure on hospitalization for chronic kidney disease. Toxics 12, 898 (2024).

Jin, L., Zhou, T., Fang, S., Zhou, X. & Bai, Y. Association of air pollutants and hospital admissions for respiratory diseases in Lanzhou, China, 2014–2019. Environ. Geochem. Health 45, 941–959 (2023).

Han, M. H., Yi, H. J., Kim, Y. S., Ko, Y. & Kim, Y. S. Association between diurnal variation of ozone concentration and stroke occurrence: 24-hour time series study. PLoS ONE 11, e0152433 (2016).

Liang, S. et al. The influence of air pollutants and meteorological conditions on the hospitalization for respiratory diseases in Shenzhen City, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 5120 (2021).

Grzywa-Celińska, A., Krusiński, A., Dos Santos Szewczyk, K., Kurys-Denis, E. & Milanowski, J. Relationship between concentration of air pollutants and frequency of hospitalisations due to respiratory diseases. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. AAEM 31, 13–23 (2024).

Phung, D. et al. Air pollution and risk of respiratory and cardiovascular hospitalizations in the most populous city in Vietnam. Sci. Total. Environ. 557–558, 322–330 (2016).

Qin, L. et al. Seasonal association between ambient ozone and mortality in Zhengzhou, China. Int. J. Biometeorol. 61, 1003–1010 (2017).

Huang, Z. H. et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on respiratory diseases among young children in Wuhan city, China. World J. Pediatr. WJP 18, 333–342 (2022).

Luong, L. M. T. et al. Seasonal association between ambient ozone and hospital admission for respiratory diseases in Hanoi, Vietnam. PLoS ONE 13, e0203751 (2018).

Phosri, A. et al. Effects of ambient air pollution on daily hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in Bangkok, Thailand. Sci. Total. Environ. 651, 1144–1153 (2019).

Chang, Q., Zhang, H. & Zhao, Y. Ambient air pollution and daily hospital admissions for respiratory system-related diseases in a heavy polluted city in Northeast China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 10055–10064 (2020).

Jia, H. et al. Ambient air pollution, temperature and hospital admissions due to respiratory diseases in a cold, industrial city. J. Glob. Health 12, 04085 (2022).

Wu, T. et al. Acute effects of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) on hospital admissions for cardiovascular diseases in Lanzhou China: A time-series study. Environ. Sci. Eur. 34, 55 (2022).

Liu, Y., You, J., Dong, J., Wang, J. & Bao, H. Ambient carbon monoxide and relative risk of daily hospital outpatient visits for respiratory diseases in Lanzhou, China. Int. J. Biometeorol. 67, 1913–1925 (2023).

Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B. & Kenward, M. G. Distributed lag non-linear models. Stat. Med. 29, 2224–2234 (2010).

Xu, J. et al. Study on the association between ambient air pollution and daily cardiovascular death in Hefei, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 547–561 (2020).

Zhu, S. et al. Ambient air pollutants are associated with newly diagnosed tuberculosis: A time-series study in Chengdu, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 631–632, 47–55 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. Association of air pollution with the risk of initial outpatient visits for tuberculosis in Wuhan, China. Occup. Environ. Med. 76, 560–566 (2019).

Huang, K. et al. Association between short-term exposure to ambient air pollutants and the risk of tuberculosis outpatient visits: A time-series study in Hefei, China. Environ. Res. 184, 109343 (2020).

Szyszkowicz, M., Kousha, T., Castner, J. & Dales, R. Air pollution and emergency department visits for respiratory diseases: A multi-city case crossover study. Environ. Res. 163, 263–269 (2018).

Bai, L. et al. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution and acute bronchitis in children: Season and age as modifiers. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 426–433 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. Associations of short-term exposure to air pollution and emergency department visits for pediatric asthma in Shanghai, China. Chemosphere 263, 127856 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on hospitalization for acute lower respiratory infections in children: A time-series analysis study from Lanzhou, China. BMC Public Health 23, 1629 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution and collaboration of all those who participated in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wancheng Zhang, Ye Ruan and Jianglong Ling collected the data; Wancheng Zhang and Ye Ruan designed methodology; Jianglong Ling analysed the data; Wancheng Zhang led the writing of the manuscript. Ye Ruan, Wancheng Zhang and Jianglong Ling conceived the ideas, contributed critically to the drafts, and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The present study was considered exempt from institutional review board approval since the data used was collected for administrative purpose without any personal identifiers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Ruan, Y. & Ling, J. Short term effects of changes in air pollutant concentrations during peaks traffic hours on hospitalization for respiratory diseases. Sci Rep 15, 25466 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10532-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10532-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Dust air pollution and hospital visits for respiratory, cardiovascular, and eye diseases in Eastern Iran

Scientific Reports (2025)