Abstract

Micro wind power systems may serve as a source of low-carbon electricity that can be integrated into cities as opposed to utility-scale wind turbines. However, the electricity generation performance of wind turbines of all capacities is highly dependent on conditions at an installation site, which can vary widely even within the same municipal region. We assess the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions (LCGHGE) and energy payback time of a novel microturbine of 2.4-kW capacity with location-specific environmental data. Potential electricity generation was modeled in the areas surrounding two US cities with ambitious decarbonization efforts and abundant wind energy resources in different climates: Austin, Texas and Minneapolis, Minnesota. The effects of system lifetime and hub height on the potential electricity generation were investigated, which identified trade-offs in higher electricity generation for taller turbines yet higher LCGHGE from greater amounts of materials needed. The LCGHGE of micro wind modeled for Austin and Minneapolis range from 53 to 293 g CO2eq/kWh, which is higher than utility-scale wind energy but still lower than fossil fuel sources of electricity. This study highlights the variability in the LCGHGE and energy payback time of micro wind power across locations, demonstrating the value of geospatial analyses for life cycle climate change impact estimates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

New and existing low-carbon electricity sources will play a crucial role in efforts to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE). In the United States, fossil fuel combustion generates the majority of electric and non-electric energy demand, despite plans that promise to decrease GHGE across all sectors by 80% or more during the next three decades1. Cities across the United States have pledged to reduce GHGE even beyond the national commitments set forth in accordance with the Paris Agreement, largely by switching from carbon intensive fossil fuels to renewable energy systems and offsetting remaining emissions. However, these goals of substantial reductions in GHGE in the energy sector of urban areas may not necessarily be reached through conversion to 100% renewable energy, especially if novel distributed energy sources with potentially higher life cycle GHGE than their utility-scale counterparts need to be implemented to meet large populations’ electricity demands without adding long-distance transmission infrastructure and without contributing further to urban sprawl.

The life cycle GHGE (LCGHGE, also referred to as carbon footprint) associated with producing, maintaining, and decommissioning prospective energy systems must be considered for effective climate policy. Renewable energy systems require the use of materials and processes that generate GHGE, which may be non-negligible when divided by the electricity produced over the lifetime of the system, particularly for those that do not generate as much electricity as expected, either due to shortened lifespan of the system or unexpected inefficiencies. Furthermore, because the amount of electricity generated by most renewable energy systems varies greatly due to geographic and climatic factors, the life cycle impacts of a given device should be investigated through geospatial analysis to understand how the LCGHGE attributable to the electricity produced by a novel device differ by location.

Micro wind turbines, which do not have a standardized capacity range but are generally lower than 5 kW, are among the renewable energy solutions being considered for distributed electricity generation near cities2,3. Taking advantage of the nation’s high potential for wind power generation, wind capacity has expanded rapidly over the past decade in the US, even briefly surpassing coal and nuclear as the second largest source of electricity generation for a single day in the spring of 20224. The technical feasibility of harnessing wind energy is well established, particularly for utility-scale wind farms5. Large wind turbines (> 1 MW) that are properly sited in areas with high wind resources can generate electricity with minimal life cycle climate change impacts compared to other electricity resources, but there are some concerns over land use requirements, including appropriate spacing between structures, and audible or visual nuisances associated with utility-scale installations6. Integrated renewable energy technologies such as micro wind turbines can potentially be installed near urban centers and generate electricity without major land-use requirements. There are numerous designs for micro wind turbines, including horizontal and vertical axes, which can be installed at substantially lower heights than higher capacity turbines and therefore require less distance from buildings. This can provide new opportunities for situating future renewable electricity supply closer to consumers driving the demand, such as within cities, if this technology is determined to result in low LCGHGE.

Many previous life cycle assessments (LCAs) have been conducted to assess the LCGHGE of generating electricity from various wind turbines under different conditions, although some results are potentially becoming less relevant as many of these studies are now more than 10 years old and based on older climate datasets and turbine designs7. Recent studies are also available that address the variability of LCGHGE resultant from existing wind farms across locations8,9,10,11. Most wind turbines in operational wind farms are classified as large12, and wind energy LCAs tend to focus on existing installations. Khoie et al. (2021) focused on a 1.3 MW wind turbine located in the Texas Panhandle, and Alsaleh and Sattler (2019) studied a 2 MW turbine near Abilene, Texas10,11. Pilot-scale offshore wind farms have also been studied in the Mediterranean by Poujol et al. (2020)9. The results of these studies demonstrate a wide range of LCGHGE attributable to wind power, largely based on the amount of electricity produced over the lifetime of a device, which depends on both the technology and location. Dammeier et al. (2022) found a range of 4 to 56 g CO2/kWh across 26,821 wind farms installed as of 20198.

Reviewed reported LCGHGE for onshore wind power technologies range from 0.01 g CO2/kWh to over 2000 g CO2/kWh within the scientific literature13. Smaller wind turbines, however, are generally less efficient than larger turbines due to higher turbulence and more intermittent wind speeds at low altitude14,15. Very large turbines also use different transportation methods than smaller turbines, travel additional distances due to availability, and need different disposal methods11, thus separate assessments are required for smaller wind turbines. Additionally, these smaller wind turbines and wind farms with short lifetimes are likely to have higher impacts as less electricity is generated throughout their life cycle. One study found that there is generally a negative correlation between the carbon footprint and rotor diameter for wind technologies16. A geospatial life cycle assessment (LCA) of small wind turbines in Austria has demonstrated that their potential LCGHGE are greater than the maximum of 16 g CO2eq/kWh required to meet Grüner Strom label certification standards17. However, the LCGHGE of micro wind installed in most other locations are unknown, as very few studies have been carried out to date on the impacts of smaller wind turbines17.

Metropolitan areas with limited land resources for utility-scale wind farms but notable wind resources, comprehensive decarbonization targets, and increasing demands for electricity are promising regions for future installations of micro wind turbines. These areas serve as useful case studies for which to model the prospective LCGHGE of these novel systems with geographically specific data. Previous work examining the climate action plans and GHG inventorying practices of different US cities identified both Austin, Texas and Minneapolis, Minnesota as having particularly ambitious climate goals that prioritize life cycle thinking18. Minneapolis pledged in its 2013 climate action plan to reduce GHGE across all sectors by 80% by 2050 as compared to 2006 levels, and Austin committed to net-zero city-wide GHGE by 2040, followed by sustained negative emissions, in its 2021 climate equity plan19,20. The regions containing the cities of Austin, Texas and Minneapolis, Minnesota have high potential for implementing wind power systems; Texas and Minnesota rank first and eighth, respectively, in installed wind capacity among US states, with abundant wind resources and relatively flat landscapes21. Austin and Minneapolis decision-makers would need geospatial LCGHGE for micro wind in their regions to compare them to other electricity resources and guide energy planning with quantifiable reductions in GHGE in line with their climate action goals.

To determine the suitability of a novel, integrated renewable technology to help cities meet their GHG reduction commitments, LCA methods were used to calculate the carbon footprint of the electricity generation modeled for a 2.4 kW capacity micro wind turbine for different areas within Austin, TX and Minneapolis, MN based on geographically specific wind resource data. For each location, we investigated the effects of hub height and system lifetime on the life cycle impacts of the average 1 kWh of electricity generated by the device. The impacts were compared against the carbon footprint of alternative energy sources in these regions and used to determine the energy payback time for electricity generated in each location.

Methods

Turbine description and data collection

The Skystream 3.7 turbine was chosen to represent an existing micro wind energy technology in this analysis as detailed technical specifications for this design were available online (Table 1)22,23,24,25, which were used to inform the baseline input parameter values and the life cycle processes modeled (Fig. 1). The Skystream is also one of many wind turbines included in the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) System Advisor Model (SAM), which provides annual electricity generation calculated from hourly weather data (air pressure, temperature, and wind speed and direction) for the years 2007 to 2014 at fine spatial resolution across the US26,27. The turbine has been tested for performance potential by the Small Wind Certification Council (SWCC), which aligns with ISO standards and is accredited by the American Association of Laboratory Accreditation, and by the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), which provided the details on specific materials comprising the turbine elements as well as the basis for an additional high-performance scenario28,29,30.

The Skystream 3.7 consists of a three-blade, horizontal axis turbine with a tubular steel tower with galvanized finish, a permanent magnet brushless steel alternator estimated at 20 kg based on various retail options available, and water-resistant wiring. The fiberglass composite components, which include the nacelle and the three blades, are estimated at 28 kg in total mass. Small elements such as steel nuts and bolts for assembly have been excluded from the scope of this analysis, as has packaging, because these minor materials are assumed to cumulatively comprise less than 1% of the overall LCGHGE. The concrete base required to support the tower is 3.3 m3 in volume, but may change slightly based on soil type, climatic conditions, and tower height and mass in practice. We modeled the same volume of concrete support for both the minimum and maximum tower heights, assuming that the large volume recommended by the installation manual is capable of supporting either tower size24. The mass of the 30-meter tower (i.e., the maximum height supported by the device) is assumed to be three times the mass of the 10-meter tower (minimum tower height) in modeling the steel life cycle impacts.

Geographic scenarios

The geographic scenarios analyzed involved fifteen zip codes in Austin (78645, 78734, 78738, 78736, 78737, 78619, 78610, 78747, 78719, 78617, 78725, 78653, 78660, 78664, 78613) and 11 zip codes in Minneapolis (55412, 55411, 55405, 55410, 55419, 55417, 55406, 55414, 55413, 55418). These zip codes are directly against yet still within Minneapolis and Austin’s city limits; they are thus within the jurisdiction of the cities’ climate action plans. These peri-urban regions would potentially be the most suitable areas within the cities for micro wind turbine installation; more densely populated and highly developed neighborhoods would feature fewer opportunities for micro wind turbine installation as the turbine requires a lot size of 0.5 acres (0.2 hectares)25. It was outside of the scope of this study to consider the suitability of individual sites for installation, i.e., lot size and zoning requirements.

To develop the 26 geographically specific LCA scenarios, zip code level data on electricity generation over time by the Skystream 3.7 turbine was retrieved from NREL’s System Advisory Model (SAM) V 12.2 (Fig. 2). SAM uses sub-hourly weather data including wind speed and direction, assuming a shear coefficient of 0.14, wake losses of 1.1%, availability losses of 5.5%. electrical losses of 2%, turbine performance losses of 4%, environmental losses of 2.4%, and curtailment losses of 2.8%27. Its high temporal resolution of 15 min for location-specific wind speeds enables precise calculations for electricity generation over time. The weather data for the years 2007 to 2014 was used to calculate the average annual electricity generation by the micro wind turbine for each zip code scenario, which was then applied to represent the turbine’s electricity generation during its first year. Subsequently, this generation was decreased by a constant factor in calculating the electricity generated during each year of the turbine’s lifetime. Although the degradation in efficiency is unknown for micro wind technology, it is assumed in this study to be 0.5%, approximately matching the performance degradation rate of utility-scale wind turbines in the US that were installed prior to the Production Tax Credit31.

In addition to the geographic scenarios, an LCA scenario was developed to represent the conditions expected by the manufacturer for the turbine lifetime and the Small Wind Certification Council’s (SWCC) determination that the Skystream 3.7 turbine can theoretically generate 3420 kWh annually28. This SWCC scenario represents a high performance that is beyond the productivity achievable in the geographic scenarios assessed (Fig. 2), and it is roughly equivalent to placing the turbine in a location that experiences a constant wind speed of 5 m/s instead of the natural fluctuations that are modeled in the geographic scenarios28. Although this does not match the zip-code level amounts of electricity generated calculated in this study (Fig. 2), this total of 3420 kWh/year may be achievable if finer spatial resolution data for wind potential is used to site a turbine strategically within a zip code. For this SWCC scenario, a distance between the manufacturer and the installation site of 2000 km (the minimum distance of the geographic scenarios) and a turbine lifetime of 20 years were modeled.

Average annual electricity generation by zip code for a micro wind turbine at: (a) the minimum hub height of 10 m in Austin, Texas, (b) the maximum hub height of 30 m in Austin, Texas, (c) the minimum hub height in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and (d) the maximum hub height in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The white areas in the center of each map represent zip codes that were not analyzed due to higher population densities affecting potential land availability.

Functional unit & impact assessment methods

The climate change impact is scaled to the functional unit of 1 kWh electricity generated by the Skystream 3.7 turbine. The results are expressed in units of g CO2eq/kWh, with all non-CO2 GHGs normalized according to the sixth IPCC report’s 100-year horizon for global warming potentials relative to CO2. The analyses were performed in Mathematica 13.0 notebooks as looped sets of equations. Life cycle inventories were collected from the Ecoinvent 3 and USLCI databases, depending on availability and relevance, using SimaPro 9.2 (Table 2). Because the exact locations of manufacturer and vendors are unknown, market inventories were chosen where available, which include global average transportation impacts. The cut-off method was used in choosing inventories, which attributes zero burden or benefit to recycling. This method is more conservative in assessing environmental impacts and prevents overestimating the benefits of recycling materials that do not replace primary production of new materials32.

Energy payback time

The energy payback time (EPBT) of renewable energy systems determines the number of years until the system has generated the amount of energy that matches the energy demand of manufacturing, transporting, and ultimately disposing of the device. This is useful for planning a rapid energy transition under resource constraints and can help avoid siting renewable energy systems in poorly performing locations. Ideally, the EPBT of a renewable energy system would be a small fraction of its lifetime; a system with an EPBT close to the lifetime of the system would not be appropriate to implement from a resource conservation standpoint. Results from EPBT studies can be used to compare across technologies and locations. The same system boundaries as the LCA were followed for the EPBT analyses, and the same inventories were selected from databases in SimaPro 9.2 for consistency, with the fossil fuel demand impact category assessed using EPA TRACI 2.1. The EPBT analysis was also performed in Mathematica as a looped set of equations by essentially dividing the total fossil fuel energy estimated to manufacture and install the device by the average amount of electricity it can generate in a year.

Results and discussion

Geographic scenario results for Austin and Minneapolis

The life cycle greenhouse gas emissions (LCGHGE) results for the micro wind turbine are strongly influenced by the wind generation potential at each location. The impacts are highest in areas with lower electricity production over time, as expected in LCAs of renewable energy systems. For the minimum hub height (10 m) scenarios across the 15 peripheral zip codes of Austin, Texas, the LCGHGE range from 77 to 276 g CO2eq/kWh. The range of results shifts to 91 to 236 g CO2eq/kWh in the same locations when the maximum hub height of 30 m is modelled instead, with only one of the zip codes showing a decrease in LCGHGE at maximum hub height. This suggests that even though increasing the hub height of the device generally increases the electricity production, it does not necessarily reduce the LCGHGE in all locations. Because of the high carbon intensity of steel production, there appears to be a limit to the benefits of increasing the hub height of the device (Fig. 3). The difference between minimum and maximum hub height results is even more apparent in Minneapolis, where the LCGHGE at the minimum hub height modelled range from 219 to 293 CO2eq/kWh, and from 176 to 239 g CO2eq/kWh at the maximum hub height. Unlike the Austin scenarios, all Minneapolis geospatial scenarios showed a decrease in LCGHGE at maximum hub height. According to the data retrieved, the electricity generation potential is much greater in Minneapolis at the higher hub height compared to the difference between hub heights in Austin. In every studied zip code across Minneapolis, electricity generation increased at least 100% at the 30-meter hub height relative to the minimum hub height, whereas only one zip code in Austin achieved the same magnitude of increase.

The entire range of LCGHGE of electricity generated by a micro wind turbine installed in the zip codes analyzed in Austin and Minneapolis is lower than the LCGHGE attributable to coal- or natural gas-fired electricity, the primary sources of fossil-based electricity in the US33,34. The micro wind LCGHGE results are also lower than regionalized emissions factors as calculated on a life cycle basis for the respective counties, and those reported by eGRID for the respective grid connections35,36. Austin is contained within Travis County, and Minneapolis within Hennepin County, where Chen & Wemhoff (2021) determined grid electricity LCGHGE to be 430 and 549 g CO2eq/kWh, respectively35. The 2025 US EPA update to the eGRID Power Profiler reports direct combustion emissions factors of 336 g CO2eq/kWh for the ERCOT region consisting of most of Texas, including the Austin area, and 420 g CO2eq/kWh for the MROW region that includes Minneapolis, for the year 202137.

Average life cycle greenhouse gas emissions (LCGHGE) by zip code for a micro wind turbine at: (a) the minimum hub height of 10 m in Austin, Texas, (b) the maximum hub height of 30 m in Austin, Texas, (c) the minimum hub height in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and (d) the maximum hub height in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The incomplete value for the zip code 78,719 located in the Southeast of Austin is 133 g CO2eq/kWh.

Because the LCGHGE of a given renewable energy system are often highly dependent on the amount of electricity generated throughout the operational lifetime38,39, extending the lifetime of a system can decrease the LCGHGE, if the contribution of decreased efficiency with aging and more frequent or intensive maintenance or replacement of parts does not negate the benefits. We investigated the effect of extending the lifetime of the micro wind turbine from 20 to 30 years, assuming that the device would remain functional over this timespan without requiring replacement of major parts, as 30 years is within the estimated lifetime range of many utility-scale wind turbines40 and the actual lifetimes of micro wind systems are currently unknown. Increasing the lifetime of the device does substantially decrease the LCGHGE of an average kilowatt-hour of electricity generated by a micro wind turbine modeled for conditions in Austin and Minneapolis, by about 32% across the scenarios, as expected (Fig. 4).

Extended lifetime scenario results of average life cycle greenhouse gas emissions (LCGHGE) by zip code for a micro wind turbine at: (a) the minimum hub height of 10 m in Austin, Texas, (b) the maximum hub height of 30 m in Austin, (c) minimum hub height in Minneapolis, Minnesota, (d) maximum hub height in Minneapolis.

SWCC scenario results

The SWCC scenario results effectively represent the “best case” scenario for the LCGHGE of the microturbine due to the higher estimated electricity generation28. Increasing the electricity generation to 3420 kWh per year for the full 20 years of operation reduces the impact to 56 g CO2eq/kWh in our model (Table 3). However, the zip-code level annual electricity output as calculated by the NREL System Advisor Model only surpassed a cumulative 3000 kWh/year at the 30-m (maximum) hub height, and only in a few zip codes in Austin. This suggests that, although the amount of electricity generated in this scenario is not technically impossible, it is unlikely that the device could meet this productivity in most of our studied regions. This is particularly less likely to occur longer into the lifetime of the turbine due to degrading performance. Still, this information could be useful for selecting optimal installation sites; locations that result in at least approximately 3420 kWh of annual generation under realistic calculations at high temporal resolution could be considered suitable for providing low-carbon electricity with micro wind turbines.

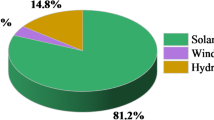

The life cycle GHGE of generating electricity with this novel microturbine in the case study locations and even in the high-performance SWCC scenario are higher than most reported emissions for utility-scale wind electricity, although lower than those of grid electricity at 430 g CO2eq/kWh in Austin and 549 g CO2eq/kWh in Minneapolis8,35,41. Previous studies have demonstrated that smaller wind turbines generally have higher associated LCGHGE than utility-scale turbines due to higher material needs relative to their electricity output16,42. However, there are still benefits to smaller-scale systems such as their lower land-use requirements and their ability to be integrated into urban environments3. As in utility-scale wind turbine LCAs19, the raw material extraction and manufacturing phases contribute the majority of the life cycle GHG emissions for the micro wind turbine, and end-of-life management activities contribute the least (Fig. 5).

Energy payback time

There is a relatively tight range of results for the energy payback time (EPBT) in both study locations. Across the zip codes assessed in Austin, the average EPBT ranges from 0.45 to 1.61 years under minimum hub height conditions and 0.5 to 1.3 years under maximum hub height conditions. These results are slightly higher across the studied zip codes in Minneapolis; the minimum hub height EPBT ranges from 1.3 to 1.7 years and the maximum hub height EPBT ranges from 1 to 1.3 years (Fig. 6). As with the LCA results, the lowest energy payback times correspond to areas of consistently high wind speeds. These results are more aligned with the EPBT of electricity from other wind turbines in the literature. A comparison of a 250 W and 4.5 MW turbine in France by Tremeac and Meunier (2009) determined that the smaller turbine had an EPBT of just over 2 years and the larger turbine showed an EPBT of 0.6 years43. Other studies have reported that the EPBT of wind turbines is generally less than one year, across various sizes of turbines44,45,46. No degradation was modelled for the energy payback analysis, as the effect would be nonexistent or negligible in all scenarios as it was applied on an annual timestep.

Upfront greenhouse gas burden

Although one of the best ways to compare the LCGHGE of alternative sources of electricity is on the basis of a kWh delivered, this does not accurately reflect the temporal distribution of emissions associated with renewables compared to fossil fuel alternatives. In contrast to fossil fuel-sourced electricity, the vast majority of the climate change impacts resultant from renewable energy systems occur from manufacturing the devices. The upfront greenhouse gas burden was estimated using the same process equations, except landfilling, simply not scaled to any amount of electricity generation. Using our baseline parameters and 2,000 km for transportation distance, the upfront greenhouse gas burden was 3641 kg CO2eq/turbine. The upfront greenhouse gas burden is reduced to 3581 kg CO2eq/turbine when assessing on a cradle-to-gate scope without shipping impacts. This value can be used to estimate the geospatial carbon footprint for any location covered in the System Advisor Model by NREL by dividing the upfront burden by the amount of electricity the device can generate over its lifetime. This can also be used for GHG inventory purposes, for a more accurate understanding of the relatively high emissions resultant from the energy transition short-term to meet net-zero goals on a long-term basis.

Recommendations and future research

Based on the results of this analysis, there may be ways to minimize the LCGHGE associated with producing electricity from micro wind in urban settings. Because the LCGHGE greatly depend on the amount of electricity generated over the lifetime of the device, increasing the lifetime or otherwise increasing the total generation ultimately decreases the associated GHGE per kWh delivered. Results suggest that increasing the lifetime by replacing and refurbishing parts as they age past the manufacturing guidelines may further decrease the life cycle carbon footprint, although we did not model the need for additional parts. Future research to assess the relative effects of replacing individual components on the lifetime and LCGHGE is needed. The mass of steel contributes significantly to the overall LCGHGE, especially for the maximum hub height scenarios, suggesting it is not always advantageous to install the maximum allowable tower at a given site. Both steel and concrete are currently active areas of research for decarbonization due to the high carbon intensity of their production processes47,48. Future research could investigate how technological advancements in cement and/or metals manufacturing affect the LCGHGE and EPBT of micro wind turbines.

The data used for this study, reflecting conditions from 2007 to 2014, may not be entirely representative of current or future wind resource availability, but was the best data fit given the hub height of this particular wind turbine, as more recent wind data is only available for higher hub heights. Additional research on the potential effects of climate change on wind speeds and consistency, as well as more recent data, could yield more relevant results for planning. Using data with a finer spatial resolution or point data within studied zip codes may help find the most suitable sites, in terms of both land requirements and minimizing LCGHGE.

Climate action policy implications

Switching from coal and natural gas-fired electricity to renewable energy is one of the main ways cities plan to reduce GHG emissions in the coming decades. Climate action plans and GHG inventories that ignore the LCGHGE of renewably sourced electricity overestimate the net reduction in emissions achieved by switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy systems that still require some infrastructure and therefore have a measurable carbon footprint18. Many cities’ GHG inventories, including Austin and Minneapolis, currently assume that electricity produced from any renewable energy system has zero associated emissions, but some cities have expressed interest in incorporating LCA results into their GHG inventories for more accurate estimates19,20. This work can be useful for policy-makers interested in including LCGHGE of renewable energy systems into their greenhouse gas inventories. Our results demonstrate that using LCA input data at a higher spatial resolution than municipal or regional scale and that assessing geographic scenarios delineated even at sub-city scales can help optimize the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy technologies, by ensuring that decision-makers have the necessary knowledge to choose the option with the lowest carbon footprint for a given location, or the site with the lowest resulting carbon footprint for a given technology. For our study locations, this specific technology does not appear to be suitable for generating electricity with the lowest possible emissions on a life cycle basis, especially compared to utility-scale renewable systems. Future research could investigate other options for novel, integrated renewables with lower life cycle emissions.

Conclusions

This research contributes to the growing field of geospatial life cycle assessment for renewable energy systems, identifying geographic differences in the carbon footprint of micro wind power that exist even at the sub-municipal scale. Our results demonstrate that the carbon footprint of new technologies should be assessed at the finest spatial resolution feasible for the most accurate understanding of the renewable resource harnessed, in this case wind. We found that throughout Austin and Minneapolis, the LCGHGE and EPBT of electricity generated by a microturbine vary appreciably and are largely dependent on the local wind speeds over time. Furthermore, although a larger amount of electricity can be generated due to higher wind speeds at the maximum hub height of 30 m compared to the minimum hub height of 10 m, the LCGHGE associated with the increase in infrastructure materials can reduce the benefits to the overall LCGHGE of micro wind power.

Data availability

All files to reproduce the analysis will be made available by the authors upon request. They are not openly shared due to the terms of use for Ecoinvent life cycle inventory data.

References

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2021). Electric Power Annual (2020). http://www.eia.gov/electricity/annual/pdf/epa.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2022.

Project Drawdown, Micro Wind Turbines, Drawdown.Org (n.d.). https://drawdown.org/solutions/micro-wind-turbines. Accessed 1 April 2024.

Gil-García, I. C., García-Cascales, M. S. & Molina-García, A. Urban wind: An alternative for sustainable cities. Energies 15, 4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/EN15134759 (2022).

U.S. Energy Information Administration. Wind was the second-largest source of US electricity generation on March 29. (n.d.). https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=52038. Accessed 2 Nov 2022.

Archer, C. L. & Jacobson, M. Z. Evaluation of global wind power. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 110, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JD005462 (2005).

Wang, S. & Wang, S. Impacts of wind energy on environment: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 49, 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2015.04.137 (2015).

Dolan, S. L. & Heath, G. A. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of Utility-Scale wind power: systematic review and harmonization. J. Ind. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00464.x (2012).

Dammeier, L. C., Bosmans, J. H. C. & Huijbregts, M. A. J. Variability in greenhouse gas footprints of the global wind farm fleet. J. Ind. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/JIEC.13325 (2022).

Poujol, B. et al. Site-specific life cycle assessment of a pilot floating offshore wind farm based on suppliers’ data and geo-located wind data. J. Ind. Ecol. 24, 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/JIEC.12989 (2020).

Khoie, R., Bose, A. & Saltsman, J. A study of carbon emissions and energy consumption of wind power generation in the panhandle of Texas. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy. 23, 653–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10098-020-01994-W/FIGURES/8 (2021).

Alsaleh, A. & Sattler, M. Comprehensive life cycle assessment of large wind turbines in the US. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy. 21, 887–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10098-019-01678-0/TABLES/18 (2019).

Hartman, L. Wind Turbines: the Bigger, the Better, Department of Energy. (2022). https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/wind-turbines-bigger-better. Accessed 31 Aug 2022.

Carbajales-Dale, M. Life cycle assessment: A meta-analysis of cumulative energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions for wind energy technologies. In Wind Energy Engineering: Handbook of Onshore Offshore Wind Turbines 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-99353-1.00028-1 (2023).

KC, A., Whale, J. & Urmee, T. Urban wind conditions and small wind turbines in the built environment: A review. Renew. Energy. 131, 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RENENE.2018.07.050 (2019).

Reja, R. K. et al. A review of the evaluation of urban wind resources: Challenges and perspectives. Energy Build. 257, 111781. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENBUILD.2021.111781 (2022).

Bhandari, R., Kumar, B. & Mayer, F. Life cycle greenhouse gas emission from wind farms in reference to turbine sizes and capacity factors. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123385. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2020.123385 (2020).

Zajicek, L., Drapalik, M., Kral, I. & Liebert, W. Energy efficiency and environmental impacts of horizontal small wind turbines in Austria. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 59, 103411. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SETA.2023.103411 (2023).

Pfadt-Trilling, A. R. & Fortier, M. O. P. Greenwashed energy transitions: are US cities accounting for the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of energy resources in climate action plans? Energy Clim. Change. 2, 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egycc.2020.100020 (2021).

City of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Climate Action Plan. (2013). http://www.minneapolismn.gov/www/groups/public/@citycoordinator/documents/webcontent/wcms1p-109331.pdf. Accessed 18 May 2020.

City of Austin, Austin Climate Equity Plan. (2021). http://austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Sustainability/Climate%20Equity%20Plan/Climate%20Plan%20Full%20Document__FINAL.pdf. Accessed 8 November 2021.

Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, WINDExchange: U.S. Installed and Potential Wind Power Capacity and Generation, Department of Energy. (2022). https://windexchange.energy.gov/maps-data/321. Accessed 4 Sept 2022.

Desert Power Inc, Skystream 3.7 Technical Specifications. (n.d.). http://www.desertpowerinc.com/pdf/0370_skystream_spec.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2022.

Southwest Windpower Inc, Skystream 3.7 Owners Manual. (n.d.). https://shop.solardirect.com/pdf/wind-power/skystream_manual.pdf. Accessed 24 April 2022.

Southwest Windpower Inc, Skystream Segmented Tower Manual. (n.d.). https://shop.solardirect.com/pdf/wind-power/skystream_segmented_tower_manual.pdf. Accessed 24 April 2022.

Skystream 3. 7 Brochure, Skystreamenergy.Com (n.d.). https://shop.solardirect.com/pdf/wind-power/skystream_brochure.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2022.

Blair, N. et al. System Advisor Model (SAM) General Description (Version 2017.9.5). (2018). https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/70414.pdf. Accessed 17 March 2022.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory, System Advisor Model. (2021).

Small Wind Certification Council, Summary Report SWCC-10-20. (2019). https://smallwindcertification.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Summary-Report-10-20-20190709.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2022.

Accreditation—Small Wind Certification. (n.d.). https://smallwindcertification.org/company/accreditation/#. Accessed 23 July 2024.

Small Wind Certification Council, Standards. (n.d.). https://smallwindcertification.org/resources/standards/. Accessed 19 Sept 2024.

Hamilton, S. D., Millstein, D., Bolinger, M., Wiser, R. & Jeong, S. How does wind project performance change with age in the united states?? Joule 4, 1004–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOULE.2020.04.005 (2020).

Zink, T. & Geyer, R. Material recycling and the myth of landfill diversion. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12808 (2019).

Whitaker, M., Heath, G. A., O’Donoughue, P. & Vorum, M. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of Coal-Fired electricity generation. J. Ind. Ecol. 16, S53–S72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00465.x (2012).

O’Donoughue, P. R., Heath, G. A., Dolan, S. L. & Vorum, M. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of electricity generated from conventionally produced natural gas. J. Ind. Ecol. 18, 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12084 (2014).

Chen, L. & Wemhoff, A. P. Predicting embodied carbon emissions from purchased electricity for united States counties. Appl. Energy. 292, 116898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116898 (2021).

US EPA, eGrid with 2021 Data. (2023). https://www.epa.gov/egrid/download-data. Accessed 27 Feb 2023.

US EPA, Summary Data eGrid with 2023 Data. (2025). https://www.epa.gov/egrid/summary-data. Accessed 22 Jan 2025.

Amponsah, N. Y., Troldborg, M., Kington, B., Aalders, I. & Hough, R. L. Greenhouse gas emissions from renewable energy sources: A review of lifecycle considerations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 39, 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2014.07.087 (2014).

Asdrubali, F., Baldinelli, G., D’Alessandro, F. & Scrucca, F. Life cycle assessment of electricity production from renewable energies: Review and results harmonization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 42, 1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2014.10.082 (2015).

Mello, G., Ferreira Dias, M. & Robaina, M. Wind farms life cycle assessment review: CO2 emissions and climate change. Energy Rep. 6, 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EGYR.2020.11.104 (2020).

Mendecka, B. & Lombardi, L. Life cycle environmental impacts of wind energy technologies: A review of simplified models and harmonization of the results. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 111, 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2019.05.019 (2019).

Caduff, M., Huijbregts, M. A. J., Althaus, H. J., Koehler, A. & Hellweg, S. Wind power electricity: The bigger the turbine, the greener the electricity? Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 4725–4733. https://doi.org/10.1021/ES204108N/SUPPL_FILE/ES204108N_SI_001.PDF (2012).

Tremeac, B. & Meunier, F. Life cycle analysis of 4.5 MW and 250 W wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13, 2104–2110. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2009.01.001 (2009).

Crawford, R. H. Life cycle energy and greenhouse emissions analysis of wind turbines and the effect of size on energy yield. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13, 2653–2660. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2009.07.008 (2009).

Guezuraga, B., Zauner, R. & Pölz, W. Life cycle assessment of two different 2 MW class wind turbines. Renew. Energy. 37, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RENENE.2011.05.008 (2012).

Bonou, A., Laurent, A. & Olsen, S. I. Life cycle assessment of onshore and offshore wind energy-from theory to application. Appl. Energy. 180, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APENERGY.2016.07.058 (2016).

Pisciotta, M. et al. Current state of industrial heating and opportunities for decarbonization. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 91, 100982. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PECS.2021.100982 (2022).

Daehn, K. et al. Innovations to decarbonize materials industries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021. 7 (7), 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-021-00376-y (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship Program (award #2139297) for funding Alyssa Pfadt-Trilling in this research. This work was also funded in part through NSF Grant #2316124 (originally #2046512 before institutional transfer), as its first iterations were completed in the Geospatial Life Cycle Assessment course developed by corresponding author Fortier through this grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P-T. conceptualized the study, performed the analyses, and wrote the main manuscript text. M-O.P. supervised the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors secured funding, developed methodology, and contributed to data visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pfadt-Trilling, A.R., Fortier, MO.P. Carbon footprint and energy payback time of a micro wind turbine for urban decarbonization planning. Sci Rep 15, 25237 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10540-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10540-x