Abstract

With the exponential growth in the quantity and complexity of malware, traditional detection methods face severe challenges. This paper proposes GCSA-ResNet, a novel deep learning model that significantly enhances malware detection performance by integrating the Global Channel-Spatial Attention (GCSA) module with ResNet-50. The core innovation lies in the GCSA module, which for the first time collaboratively designs channel attention, channel shuffling, and spatial attention mechanisms to simultaneously capture local texture features and global dependency relationships in visualized malware images. Compared with existing attention models such as SE and CBAM, GCSA strengthens cross-channel information interaction through channel shuffling operations and employs spatial attention with a 7 × 7 convolutional kernel to more effectively model long-range spatial correlations. Experiments on the Malimg and Microsoft BIG 2015 datasets demonstrate that GCSA-ResNet achieves over 98.50% accuracy, representing a performance improvement of more than 0.5% compared to baseline models. Quantitative results show that the model maintains stable performance in precision, recall, and F1-score, while reducing false positive rates by 40–50%. These advancements effectively address the limitations of existing methods in feature degradation and cross-family misclassification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of information technology has positioned malware as one of the most significant threats in the realm of cybersecurity. The variety and volume of malware are growing exponentially, with attack methodologies becoming increasingly sophisticated. From traditional viruses and worms to advanced persistent threats (APTs) and ransomware, the targets of malware attacks span individual users, enterprises, and even national critical infrastructure. According to the latest cybersecurity reports, the number of new malware samples detected globally each day has surpassed millions, posing severe challenges to traditional malware detection techniques. Conventional detection methods primarily rely on signature matching and heuristic analysis, which often fall short when confronted with novel malware variants and obfuscation techniques. Consequently, the efficient and accurate detection and classification of malware have emerged as critical issues in the field of cybersecurity.

Currently, most deep learning-based malware classification and detection methods1 involve converting malware samples into visual representations, where convolutional neural networks automatically extract high-dimensional features from these malware images to determine the family to which the samples belong. These deep learning-based approaches do not require executing the malicious code, retaining the advantage of static analysis methods in terms of low resource consumption. Moreover, during the visualization process, they can effectively leverage the characteristic features of malware families, making them resistant to obfuscation and packing techniques, thereby improving classification accuracy.

Although deep learning has demonstrated significant potential in malware detection, its practical application still faces challenges such as data imbalance and poor model interpretability. For instance, CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module)2 employs global average pooling and max pooling to generate channel attention, but such simplistic aggregation may lose critical local features, potentially lacking sensitivity to subtle yet decisive patterns in malware images. Meanwhile, the SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation)3 module entirely overlooks spatial attention, whereas spatial relationships (e.g., texture distribution) in malware visualization are crucial for classification. This study aims to explore the application of ResNet model variants in malware detection and classification, addressing the limitations of traditional methods and existing deep learning models in this domain.

· We designed a Global Channel-Spatial Attention (GCSA) module to enhance the expressive power of input feature maps. This module combines channel attention, channel shuffle, and spatial attention mechanisms to capture global dependencies within feature maps.

· Single neural network models often struggle to accurately capture the intricate details of images in classification tasks and exhibit insufficient generalization capabilities, leading to fluctuating classification effectiveness across different scenarios and data distributions. The integration of GCSA with ResNet effectively addresses these issues.

· The GCSA-ResNet model combines various structures, with GCSA comprehensively considering global channel and spatial characteristics and thoroughly mixing the extracted low-level features, which are then subjected to high-level feature extraction through ResNet4. This integrated feature extraction helps reduce misjudgments and biases in the model’s understanding of complex images, achieving superior classification performance in multi-class tasks compared to other hybrid neural network models.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. Related work presents a comprehensive review of related work in malware visualization and detection, with particular emphasis on recent advancements in deep learning-based methodologies. Section Model design provides a detailed exposition of the proposed GCSA-ResNet architecture, encompassing both the novel Global Channel-Spatial Attention mechanism and its seamless integration with the ResNet framework. Section Experiments and results systematically documents the experimental methodology, including dataset specifications, evaluation protocols, and comparative analysis against state-of-the-art techniques. Finally, Sect. Conclusions concludes the paper by summarizing key findings and outlining promising avenues for future research.

Related work

Malware detection

In recent years, deep learning technologies have achieved remarkable success in areas such as image recognition and natural language processing5. Their robust feature extraction and pattern recognition capabilities offer new perspectives for malware detection and classification. By transforming malware binary files into images or sequential data, deep learning models can autonomously learn the characteristics of malware, enabling effective detection and classification. For instance, Daniel Gibert and Carles Mateu6 introduced a file-agnostic deep learning approach that extracts a set of discriminative patterns from visualized images of malware, utilizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) to efficiently group malware into families, thereby showcasing its robust performance. Abien Fred M. Agarap7 proposed an intelligent anti-malware system that combines deep learning (DL) models with Support Vector Machines (SVM) for malware classification. The system trained three DL models—CNN-SVM, GRU-SVM, and MLP-SVM—for malware family classification, with the GRU-SVM model demonstrating the highest prediction accuracy. Cornelius Paardekooper8 employed Genetic Algorithms (GA) to optimize the topology and hyperparameters of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for image-based malware classification. The algorithm generates new network architectures through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, automatically designing efficient and compact CNN networks that reduce resource consumption while maintaining or enhancing classification performance. Marcelo Invert Palma Salas9 utilized the Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge dataset to adapt models via transfer learning for malware classification tasks, improving efficiency and accuracy. Bassam Al-Masri10 proposed a DCNN-based architecture for malware classification, which first converts malware binary files into 2D grayscale images and then trains a custom dual CNN for multi-class malware classification. Zhong, Fangtian11 introduced the VisMal framework, which transforms malware samples into images and applies Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization to enhance the similarity between regions of malware images within the same family. Chaganti, Rajasekhar12 proposed an efficient neural network model, EfficientNetB1, for malware family classification using byte-level image representations. Bao, Huaifeng13 presented MalAtt, a unified feature engineering approach for malware classification that derives integrated embeddings from heterogeneous static and dynamic information, employing a hierarchical attention encoder module to progressively extract semantic features from static and dynamic embeddings. A collaborative attention module was introduced to model the associations between high-level static and dynamic features. Ismail, Setia Juli Irzal14 proposed a self-supervised learning-based method for malware classification using image representations. Miao, Chunyu15 proposed a novel lightweight malware detection method based on knowledge distillation, where a student network learns valuable hints from a teacher network to achieve a lightweight model with improved performance. Darem, Abdulbasit A16. introduced a novel malware detection method based on deep learning, integrating four base classifiers: LightGBM, XGBoost, CNN, and LSTM.

Lu, Qikai17 designed a file-size-aware two-stage framework combining SeqConvAttn and ImgConvAttn to balance the accuracy and latency of real-time classification. Kale, Gulsade18 employed a Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) in machine learning (ML) to select key and decisive features for malware detection. Andrade, Eduardo de O19. used word embedding algorithms and Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM) to address binary and multi-class malware classification problems. Alandjani, Gasim20 proposed a novel deep network with dual attention feature refinement on a dual-branch deep network, utilizing lightweight spatial asymmetric attention to refine the extracted features of its backbone and introducing multi-head attention to correlate learned features from network branches. Gao, Xianwei21 proposed a novel packed malware family classification framework combining a Packer detector, malware classifier, and Packer Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Chong, Xulei22 proposed a malware family classification method based on the fusion of Efficient-Net and 1D-CNN, extracting texture features of malware using a 2D convolutional architecture network and local adjacent information features using a 1D convolutional network, fusing deep features from different networks and modifying both networks simultaneously during backpropagation. Edward Raff23 explored the challenge of processing extremely long sequence inputs within the field of machine learning, particularly in cybersecurity applications, developing a new temporal max pooling method that renders the required memory independent of sequence length T, and improving the MalConv architecture by introducing GCG. Wu, Xuan24 proposed a novel TCN-BiGRU deep learning method combining Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Units (BiGRU). Chen, Zhiguo25 used forward feature stepwise selection techniques to combine reasonable binary and assembly malware features, generating new efficient fusion features. Ashawa, Moses26 proposed an enhanced image-based malware classification system using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and ResNet-152 and Vision Transformer (ViT). Cheng-Jian Lin27 investigated the application of Taguchi method-based Deep Learning Networks (TDLN) in malware family classification, with the DLN architecture comprising three convolutional layers, three ReLU activation functions, three max pooling layers, and one fully connected layer. The Taguchi method was used to optimize DLN parameter combinations. Farfoura, Mahmoud E28. designed a machine learning (ML) model architecture specifically for malware detection, enabling real-time and accurate malware identification, using an interpolation-based feature dimensionality reduction technique (IFDRT) that significantly reduces the feature space while retaining critical information for malware classification.

Model design

Global Channel-Spatial attention

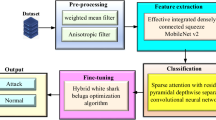

In traditional Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the relationships between channels are often overlooked, despite their critical importance in capturing global information. Neglecting these inter-channel dependencies can prevent the model from fully exploiting the information within feature maps, thereby limiting its ability to extract global features. To address this issue, we propose a Global Channel-Spatial Attention Module (GCSA), designed to enhance the expressive power of input feature maps. This module effectively captures global dependencies within feature maps by integrating channel attention mechanisms, channel shuffle operations, and spatial attention mechanisms. The specific workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Channel attention

To enhance the dependencies between channels, we introduce a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) in the channel attention submodule, which reduces redundant information among channels while highlighting critical features. Specifically, the input feature map first undergoes a dimensional permutation, transforming from C×H×W to W×H×C, thereby placing the channel dimension in the last position. Given the input feature map\(\:{F}_{input}\in\:{R}^{C\times\:H\times\:W}\), the following operations are initially performed:

Next, we model inter-channel dependencies using a two-layer MLP architecture: the first MLP layer reduces the number of channels to 1/4 of the original dimension with ReLU activation introducing nonlinearity, while the second MLP layer restores the channel dimension to its original size. This design effectively captures global dependencies among channels. The two MLP layers employ weight matrices W₁ and W₂ respectively, where \(\:{W}_{1}\in\:{R}^{\frac{C}{r}\times\:C}\:\)and\(\:{\:W}_{2}\in\:{R}^{C\times\:C/r}\) (with reduction ratio r = 4), forming a bottleneck structure that efficiently models channel-wise relationships.

Here, we set the reduction ratio r = 4 to achieve efficient channel compression, where δ(·) denotes the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function and σ(·) represents the sigmoid activation function. The weight matrices W₁ and W₂ are initialized following Xavier normal distribution to maintain stable gradient flow during training.

Subsequently, the feature map is restored to its original dimensions (C×H×W) through an inverse permutation operation P⁻¹(), followed by the generation of a channel attention map using a sigmoid activation function. Finally, the input feature map is element-wise multiplied with the channel attention map to produce enhanced features through channel-wise scaling. In this manner, the channel attention submodule effectively improves the representational capacity of feature maps while mitigating the adverse effects of redundant information on model performance.

where \(\:{F}_{channel}\)represents the enhanced feature map, \(\:\otimes\:\)denotes element-wise multiplication, and the output dimension is strictly kept as C×H×W.

Channel shuffle

To further enhance the information mixing and sharing capabilities of the feature map, we introduce a channel shuffle operation. Although the channel attention mechanism effectively captures inter-channel dependencies and highlights significant features, the information between channels may still not be fully mixed after channel attention enhancement, which could limit further improvement in feature representation. To address this issue, the enhanced feature map is divided into several groups (e.g., 4 groups), each containing C/4 channels, where C is the total number of channels. Subsequently, the grouped feature map undergoes a transpose operation to shuffle the channel order within each group. Finally, the shuffled feature map is restored to its original shape C×H×W. This channel shuffle operation promotes information interaction between different channels, thereby better mixing feature information and enhancing feature representation. This design not only fully leverages the effects of channel attention but also further improves the overall performance of the model.

Initially, a group permutation operation is conducted, wherein the Fchannel is partitioned into g = 4 distinct groups, each comprising C/g channels.

Subsequently, inter-group connectivity is constructed via a transpose operation.

where\(\:{F}_{shuffle}\) represents the shuffled feature map, and \(\:{F}_{channel}\)denotes the number of channels in the input feature map.

Spatial attention

In the spatial attention submodule, we designed a convolution-based spatial attention mechanism to fully leverage the spatial information within the feature map. While channel attention and channel shuffle operations effectively capture inter-channel dependencies and enhance feature representation, they may not fully exploit information along the spatial dimension, which is equally critical for capturing both local and global features in images. Neglecting spatial information could result in the loss of important details in the feature map, thereby limiting the model’s performance.

To address this issue, the spatial attention submodule processes spatial information through two 7 × 7 convolutional layers. First, the input feature map passes through a 7 × 7 convolutional layer, reducing the number of channels to one-fourth of the original count. Subsequently, the feature map undergoes non-linear transformation via batch normalization and a \(\:ReLU\) activation function. Next, a second 7 × 7 convolutional layer restores the channel count to the original dimension C, followed by another batch normalization layer to stabilize the training process. Finally, a spatial attention map is generated through a \(\:Sigmoid\) activation function, highlighting the important spatial regions within the feature map. The shuffled feature map is then element-wise multiplied by the spatial attention map to produce the final output feature map. Through this mechanism, the spatial attention submodule effectively captures spatial dependencies, further enhancing the model’s ability to represent both local and global features.

The spatial attention submodule takes the output feature map \(\:{F}_{shuffle}\in\:{R}^{C\times\:H\times\:W}\) from the channel shuffle operation as input, where two convolutional layers employ kernel weights \(\:{W}_{3}\in\:{R}^{C/r\times\:C\times\:7\times\:7}\) and \(\:{W}_{3}\in\:{R}^{C/r\times\:C\times\:7\times\:7}\), respectively.

In this formulation, \(\:{F}_{spatial}\) represents the spatially refined feature map, with σ(·) indicating the Sigmoid activation function. Crucially, the output maintains the original dimensional structure of C × H × W without alteration.

The rationale for employing a 7 × 7 convolutional kernel in spatial attention can be explained as follows: In conventional CNNs, while 3 × 3 convolutions can progressively expand the receptive field through stacking, multiple layers are required to achieve global perception. However, for spatial attention mechanisms, a single 3 × 3 convolution can only model local pixel relationships (9-neighborhood), making it difficult to directly capture long-range dependencies across distant regions in the image. In contrast, a 7 × 7 convolution covers a 49-neighborhood, enabling direct modeling of broader spatial contexts. This design allows the attention mechanism to capture long-range dependencies in a single layer while reducing the need for multiple attention blocks.Moreover, small convolutional kernels tend to produce attention maps that overemphasize local details, leading to abrupt changes in attention weights between adjacent regions (i.e., “fragmentation”). Such non-smooth attention distributions may disrupt feature continuity and, in malware detection tasks, result in pixel misalignment or boundary artifacts. The wider coverage of a 7 × 7 kernel inherently provides low-pass filtering characteristics, generating smoother and more coherent attention distributions.

Output feature map

The final output feature map incorporates enhanced features derived from channel attention, channel shuffle, and spatial attention mechanisms. Table 1 presents the parameter size of the GCSA model.

In malware detection tasks, the input feature map is typically an RGB image converted from a malware binary file. Initially, the channel attention submodule captures inter-channel dependencies through a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), emphasizing features from important channels and thereby reducing the impact of redundant information on model performance. Subsequently, the channel shuffle operation further mixes information across different channels, enhancing feature representation. Finally, the spatial attention submodule captures spatial dependencies via 7 × 7 convolutional layers, highlighting critical local regions in the image (e.g., code segments or resource segments), thereby enabling a more comprehensive extraction of malware features.

Mechanisms for preventing feature degradation

(1)Feature Enhancement via Multiplication (Not Replacement): Both attention branches employ multiplicative operations rather than replacement operations, preserving the fundamental information of original features. This residual-style design ensures the network can always trace back to initial features, preventing loss of critical information during attention processing.(2)Progressive Feature Transformation: The channel attention uses fully connected layers for dimension reduction-expansion (rate = 4), while the spatial attention employs 7 × 7 convolution kernels combined with BN and ReLU. Such progressive nonlinear transformations better preserve feature expressiveness compared to direct, abrupt attention weighting.(3)Channel Shuffle Operation: A channel_shuffle operation is inserted between dual attention modules, regrouping and rearranging feature channels. This operation forces information interaction between different channel groups, preventing long-term suppression of certain channels that could lead to feature degradation - conceptually similar to ShuffleNet but applied between attention mechanisms.

The channel attention first calibrates feature channels to filter out noisy ones. Then, channel shuffle disrupts the channel order to break potential fixed inter-channel dependencies. Finally, spatial attention establishes spatial relationships on the reorganized channels. This “channel filtering → channel mixing → spatial filtering” pipeline aligns better with feature processing logic than traditional parallel attention approaches, simultaneously preventing feature degradation while maintaining spatial consistency.

Differences from CBAM

Channel Attention: CBAM employs dual pooling (Avg + Max) to capture more comprehensive statistical information, while GCSA achieves this through a linear layer (similar to the SE module but with ReLU added), resulting in lighter computation. GCSA allows flexible adjustment of the reduction ratio (rate), whereas CBAM’s MLP reduction ratio is fixed (typically 1/16 of the channel count).

Spatial Attention: CBAM generates a 2-channel feature map through channel compression (Avg + Max Pooling), followed by convolution. In contrast, GCSA directly applies convolution to multi-channel feature maps, preserving richer information. Additionally, GCSA incorporates BatchNorm and ReLU to enhance nonlinear expressiveness, while CBAM relies solely on simple convolution.

Channel Shuffling: A unique operation in GCSA, channel shuffling promotes cross-channel information interaction, akin to the concept in ShuffleNet, preventing feature stagnation.

Focus and Applicability: CBAM typically emphasizes globally salient regions (relying on pooling), making it suitable for object localization in natural images. On the other hand, GCSA prioritizes local high-frequency textures (due to channel shuffling and depthwise convolution), making it more effective for structured patterns in malware images (e.g., repetitive byte sequences). Consequently, GCSA outperforms CBAM in malware visualization classification tasks.

GCSA-ResNet

This study employs ResNet50 as the foundational architecture, which constructs deep networks through the implementation of bottleneck residual blocks. ResNet (Residual Network) represents a deep convolutional neural network architecture specifically designed to address the challenges of gradient vanishing and degradation in deep neural network training. By integrating the Global Channel-Spatial Attention (GCSA) module with ResNet-50 for malware detection tasks, the model’s feature extraction capability for visualized images of malware binary files is significantly enhanced. Distinct sections of malware (such as.text,.data, and.rsrc segments) typically exhibit unique texture and spatial distribution patterns in visualized images, which are crucial for distinguishing between different malware families or types. The incorporation of the GCSA module enables ResNet-50 to more effectively capture these local and global features, thereby improving both the accuracy and robustness of malware detection.

Specifically, we designed a sequential integration of the GCSA module with ResNet-50 to leverage the strengths of both components. The malware binary file is first converted into a grayscale image and fed into the GCSA module. Within the GCSA module, the channel attention submodule initially captures inter-channel dependencies, emphasizing features from important channels. This is followed by a channel shuffle operation to mix information across different channels, enhancing feature representation. Finally, the spatial attention submodule captures spatial dependencies, highlighting critical local regions in the image (e.g., code segments or resource segments). The enhanced feature map produced by the GCSA module is then passed to the ResNet-50 network, where its deep convolutional layers further extract high-level feature representations. This sequential design leverages the strengths of both components: the GCSA module refines the input features at an early stage, enhancing their expressive power, while ResNet-50 utilizes its robust deep feature extraction capabilities in subsequent stages to further uncover complex malware features(Fig. 2: GCSA-ResNet Architecture Diagram).

The architecture is primarily divided into three key components: the Stem, Body, and Head modules.The Stem module performs initial feature extraction from the raw input images, establishing a foundational representation for subsequent processing.The Body module consists of four stages of bottleneck residual blocks, progressively extracting deeper and more discriminative features through hierarchical learning.Finally, the Head module processes the high-level features and performs the ultimate classification task.

Stem

The Stem module of ResNet50 serves as the feature extraction front-end, fulfilling dual functions of primary visual feature encoding and dimensional transition. In this study, we designed a three-stage feature processing architecture for the Stem module: Initial feature extraction and downsampling are performed using a 7 × 7 convolutional kernel (stride = 2), followed by batch normalization (BatchNorm) and ReLU activation.A 3 × 3 max-pooling operation (stride = 2) is then applied to further reduce the feature map dimensions.Additionally, we integrated the proposed GCSA module at the junction between the Stem and Body sections, incorporating it into the Stem itself. This enhancement leverages channel attention to automatically suppress redundant features and spatial attention to reinforce critical regions.

After visualization, the malware is transformed into a 4-dimensional tensor suitable for input, with a shape of \(\:X\in\:{R}^{B\times\:3\times\:H\times\:W}\), where \(\:B\) represents the batch size, 3 denotes the number of channels in the input image (RGB), and \(\:H\) and \(\:W\) correspond to the height and width of the input image, respectively.

where \(\:{W}_{1}\) represents the convolutional kernel weights and \(\:{b}_{1}\) denotes the bias term.

Body

The primary function of the Body is to progressively extract high-level features by stacking Residual Blocks, while leveraging Residual Connections to mitigate gradient vanishing and network degradation in deep architectures. This enables the network to be trained more deeply and stably.Each Residual Block extracts features through convolutional layers and incorporates a skip connection that directly forwards the input to the output. This design allows the network to learn residual mappings (Residual Mapping), leading to more efficient optimization and training.

As illustrated in the figure(Fig. 3), the ResNet50 Residual Block consists of three convolutional layers:

1 × 1 convolution: reduces dimensionality (channel compression)

3 × 3 convolution: extracts Spatial features

1 × 1 convolution: restores dimensionality (channel expansion)

The model employs four stages of residual blocks (from \(\:Layer1\) to \(\:L\text{ayer4}\)) to extract advanced features. In ResNet50, each stage contains3,3,4,6 Bottleneck blocks, respectively. The computation for each BasicBlock can be expressed as:

In the formula, \(\:{W}_{a}\)and \(\:{W}_{b}\) represent the weight matrices of the first and second convolutional layers, respectively, while \(\:{b}_{a}\)and \(\:{b}_{b}\) denote the bias terms of the first and second convolutional layers, respectively. Through the computations in the body section, we obtain the final output feature map:

Head

The classification result is generated through global average pooling and a fully connected layer. The head section consists of three stages. First, global average pooling (GAP) is applied to compress the spatial dimensions (height and width) of each channel into a 1 × 1 size, thereby summarizing each channel’s feature map into a scalar value. This reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature map while preserving the channel dimensions. Next, a flattening operation is performed to convert the tensor into a 1D vector.

Finally, a fully connected layer maps the global feature vector to the class space, generating the final classification result.

where \(\:{W}_{fc}\) represents the weight matrix of the fully connected layer, and \(\:{b}_{fc}\) denotes the bias term.

Experiments and results

Dataset

Malware visualization

Malware visualization is the process of graphically representing the complex features, behaviors, and structures of malicious software, enabling researchers to better understand and analyze its characteristics. By sequentially mapping bytecode to image pixels, recurring byte sequences in malware can form distinct visual patterns, facilitating rapid identification of similar samples.Given a malware binary file, it is first parsed into a vector of 8-bit unsigned integers, which is then reshaped into a two-dimensional array. The mapping process employs a linear sequential filling algorithm: for a target image width W and an original byte vector of length L, the image height h is determined as \(\:h=L/W\). If L is not an integer multiple of W, the remaining pixel positions are zero-padded. This array is subsequently visualized as a grayscale image, where pixel values range from [0, 255],0 representing black and 255 representing white.The image width is fixed at a predefined value W = 256, while the height dynamically adjusts according to the file size (as illustrated in Fig. 4). To enhance feature discriminability, byte-to-pixel conversion follows a direct linear mapping: for a given byte \(\:b\in\:[0x\text{00,0}x{FF}]\), the corresponding pixel value P is computed as \(\:P=round(b\times\:\text{255/0x}{FF})\). This standardized normalization ensures consistent comparability across images generated from different files.

Figure 5 illustrates a visualization of a typical Trojan downloader, Dontovo A, which possesses the capability to download and execute arbitrary files. Notably, distinct sections of the malware (i.e., binary segments) exhibit unique textural characteristics within the image. Specifically, the.text section, which contains executable code, displays fine-grained textural patterns at its beginning, while the remaining portion is padded with zeros (represented as black regions), indicating zero-padding at the end of this section. The data section comprises both uninitialized code (manifested as black blocks) and initialized data (displaying fine-grained textures). Finally, the.rsrc resource section encompasses all resources of the module, which may include icons utilized by the application, among others.

We utilized the Malimg dataset and the Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (BIG 2015) dataset for our experiments.

Malimg

The Malimg dataset29 is an image dataset designed for malware classification, where malware samples are converted into grayscale images and categorized based on their malware families. The dataset comprises approximately 9,339 malware samples distributed across 25 distinct malware families. The images are formatted as grayscale, with sizes of either 64 × 64 or 128 × 128 pixels. The frequency distribution of malware families within the dataset is presented in the accompanying table(Table 2).

Microsoft malware classification challenge (BIG 2015)

The Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (BIG 2015)30 is a widely-used dataset for malware classification, comprising approximately 21,741 malware samples categorized into 9 distinct families. Each sample is provided in the form of binary files and disassembled code, encompassing a variety of malware behaviors and techniques. The dataset’s diversity and complexity make it an ideal choice for research in malware detection and classification. However, challenges such as class imbalance, high-dimensional features, and adversarial samples pose significant hurdles for model development. The dataset is publicly available on the Kaggle platform and has become one of the benchmark datasets in the field of malware classification. For our experiments, we selected a subset of labeled data, and the frequency distribution of malware families within this subset is presented in the accompanying table(Table 3).

When partitioning the two datasets into training, testing, and validation sets, we adopted a ratio of 0.72 : 0.2 : 0.08. This partitioning strategy ensures that the majority of the data is allocated for training while retaining sufficient data for testing and validation, thereby enabling a robust evaluation of the model’s generalization capabilities and mitigating the risk of overfitting.

Experimental setup and hyperparameter design

In our experiments, all tests were implemented using the PyTorch framework (version cuda = 12.4) and Python 3.12.4. The experimental environment was configured on a high-performance server equipped with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700KF CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 GPU to ensure efficient execution and computational performance.Table 4 shows the specific settings of the experimental parameters.

Regarding the learning rate optimization, we additionally employed the Cosine Annealing Learning Rate (CosineAnnealingLR) strategy. This approach, categorized as a dynamic learning rate scheduling method, cyclically modulates the learning rate to enhance model optimization performance.

Experimental results

Evaluation metrics

In our multiclass classification framework, where each malware family is treated as a distinct class, we define:

True positives (TP)

Samples correctly classified to their true family.

False positives (FP)

Samples from other families incorrectly classified to the target family.

False negatives (FN)

Samples from the target family incorrectly classified to other families.

True negatives (TN)

Samples correctly predicted as not belonging to the target family.

Accuracy

Accuracy is the proportion of correctly predicted samples out of the total number of samples. It is the most intuitive evaluation metric.\(\:A\text{cc}uracy=\frac{TP+TN}{TP+TN+FP+FN}\)

Precision

Precision is the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to the total number of samples predicted as positive. It focuses on the accuracy of the model’s positive predictions. A higher precision indicates fewer errors among the samples predicted as positive by the model.\(\:{Pr}ecision=\frac{TP}{TP+FP}\)

Micro Recal(Recal-mic)

Recall is the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to the total number of actual positive samples. It measures the model’s ability to cover positive samples. A higher recall indicates a stronger capability of the model to identify positive samples.\(\:{Re}call=\frac{TP}{TP+FN}\)

Macro Recal(Recal-mac)

The arithmetic mean of recall scores across all classes, treating each class equally. This metric evaluates the model’s average coverage ability across all categories.\(\:Recall\_mac=\frac{1}{C}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{C}Recal{l}_{i}\)

Macro F1-score(F1-mac)

F1-macro is the arithmetic mean of the F1-scores across all classes, treating each class equally without being affected by sample size. It assigns equal weight to each class’s F1-score, regardless of class imbalance, making it particularly suitable for evaluating model performance on minority classes.\(\:F1\_mac=\frac{1}{C}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{C}F{1}_{i}\)

Micro F1 score (F1-mic)

Used to assess data with class imbalance. Reflects overall performance, suitable for class-balanced datasets.\(\:F1\_micro=\frac{2\cdot\:TP}{2\cdot\:TP+FP+FN}\)

Weighted F1 score (F1-wted)

Suitable for scenarios involving class imbalance. It reflects that it can better reflect the model performance when the class is imbalanced.\(\:F1\_weight={\sum\:}_{i=1}^{C}{w}_{i}\times\:F{1}_{i}\)

False positive rate (FPR)

Represents the proportion of actual negative samples misclassified as positive. Reflecting the proportion of false positives, low FPR means that the model has a strong ability to identify negative classes.\(\:FPR=\frac{FP}{TN+FP}\)

Diagnostic efficiency (DE)

Represents the overall accuracy rate of the model in classifying positive and negative samples. Reflecting the overall error rate, high DE means that the overall performance of the model is better.\(\:DE=\frac{FP+FN}{TP+TN+FP+FN}\)

Negative predictive value (NPV)

Represents the proportion of true negatives among the samples predicted as negative. Reflecting the reliability of the model in predicting negative classes, high NPV means fewer false positives.\(\:NPV=\frac{TN}{TN+FN}\)

Specificity (SPC)

Represents the proportion of actual negative samples correctly predicted as negative. Reflecting the model’s ability to identify negative classes, high SPC means fewer false positives.\(\:SPC=\frac{TN}{TN+FP}\)

Time

The time required to complete the model training process.

Training and testing accuracy and loss curves

These curves illustrate the trends in accuracy and loss values during the training and testing processes of the model.

Confusion matrix

The confusion matrix is a commonly used evaluation tool in classification problems, providing a visual representation of the relationship between the model’s predictions and the actual labels. The rows of the matrix represent the actual classes, while the columns represent the predicted classes.

Grad-CAM visualization

Grad-CAM highlights key regions in an image that influence a neural network’s prediction, using a heatmap (red = important, blue = less important) to show where the model focuses. This helps explain its decisions.

Model comparison

For a comprehensive performance evaluation, we conducted comparative experiments between the proposed GCSA-ResNet model and various advanced deep learning methods on two authoritative malware classification benchmark datasets: the Malimg dataset and the Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (BIG 2015) dataset. The compared models include traditional convolutional neural networks (CNN), a hybrid CNN-SVM model7, Vision Transformer (ViT)31, standard ResNet50, and two attention-enhanced ResNet variants (SE-ResNet and CBAM-ResNet). The experimental results demonstrate that our proposed GCSA-ResNet model performs exceptionally well on both the training and test sets, significantly outperforming all baseline models across all evaluation metrics. Detailed performance comparisons are provided in Tables 5 and 6.

As observed in Tables 5 and 6, Our proposed GCSA-ResNet model achieved state-of-the-art performance on both the Malimg and Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge datasets, with 99.08% and 98.58% accuracy, respectively, surpassing all compared models. It demonstrated superior balance between precision and recall, attaining the highest F1 scores (99.09% F1-mic and 98.58% F1-wei), while also excelling in recall (97.76% and 98.35%) and precision (99.08% and 98.58%). Additionally, the model maintained exceptional specificity (99.96% SPC) and low false positive rates (0.04% FPR), further validating its robustness. These results highlight GCSA-ResNet’s optimized performance, making it a highly effective solution for malware detection tasks. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the accuracy and loss curves of the GCSA-ResNet model on the training and validation sets.

Figures 8 and 9 present the confusion matrices of the GCSA-ResNet model on both datasets. The results demonstrate that for certain malware families, our model achieves 100% precision in detection, showcasing exceptional classification capabilities. However, despite the model’s high overall accuracy, some misclassifications persist for specific malware families. For instance, in the Malimg dataset, samples from the C2Lop.P family were incorrectly classified as belonging to the C2Lop.gen! G family, suggesting that these two families may exhibit highly similar or overlapping behavioral patterns. Additionally, the model encounters difficulties in distinguishing between certain families, such as Ramnit and Lollipop, likely due to their close proximity in the feature space or shared behavioral characteristics. These findings indicate that while the model exhibits outstanding overall performance, it still faces challenges when classifying malware families with highly similar features.

We also employed Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) for visualization. As shown in the figure (Figs. 10 and 11), Grad-CAM effectively highlights critical regions in malware images from both families, clearly revealing the key features influencing the model’s decisions. The color gradient represents varying importance levels, with highlighted areas (such as edges or specific texture patterns) indicating regions that played a decisive role in the classification process. This visualization intuitively demonstrates how the model makes decisions based on specific image features, significantly enhancing the transparency and credibility of the decision-making process. By revealing the model’s focus areas in malware image analysis, Grad-CAM provides robust support for model interpretability.

Ablation experiments and results

To systematically evaluate the synergistic effects of the three core modules in the GCSA architecture—Channel Attention, Channel Shuffle, and Spatial Attention—we designed comparative experiments. The GCSA-ResNet was compared with the following variant models: (1) SA-ResNet (retaining only the Spatial Attention module), (2) CA-ResNet (retaining only the Channel Attention module), and (3) CSA-ResNet (with the Channel Shuffle operation removed). As demonstrated by the ablation study results in Tables 7 and 8, the experiments not only validate the individual contributions of each module but also highlight the critical role of integrating all three components within the framework.

The ablation study demonstrates that GCSA-ResNet achieves optimal performance on both the Malimg and Microsoft malware datasets, with accuracy rates of 99.08% and 98.58%, respectively. These results significantly outperform those of single-attention variants (CA-ResNet and SA-ResNet) and their simple combination (CSA-ResNet).Key findings include: Channel attention effectively enhances specificity (SPC: 99.96%) while reducing the false positive rate (FPR: 0.04%).Spatial attention improves macro-recall (Recall-mac: 97.76%).The channel shuffle mechanism further boosts cross-channel information interaction, increasing the macro-F1 score (F1-mac: 98.34%).Although inference time increases slightly (~ 3.6%), the synergistic effect of these components validates the effectiveness of the GCSA design, providing a high-precision, low false-alarm solution for malware detection.

Conclusions

In this study, GCSA-ResNet innovatively integrates channel attention mechanisms, channel shuffle operations, and spatial attention mechanisms into the ResNet-50 architecture. By simultaneously capturing both local texture features and global dependency relationships in visualized malware images, the model achieves a remarkable detection accuracy exceeding 98.5% while reducing false positive rates by 40–50%. The proposed design effectively addresses critical challenges of feature degradation and cross-family misclassification, with its superior performance validated on benchmark datasets. However, computational costs and adversarial robustness remain as key challenges for future breakthroughs.

Future research will prioritize lightweight adaptation strategies (e.g., model quantization) for real-time deployment, hybrid architectures integrating dynamic analysis, and self-supervised/unsupervised learning techniques to extract discriminative features from unlabeled data—reducing annotation dependence while enhancing real-world generalization. Additionally, rigorous validation in environments will be conducted to bridge the gap between research and practical implementation.

Data availability

We evaluated the performance of our model using two datasets. The first is the Malimg dataset (available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1M83VzyIQj_kuE9XzhClGK5TZWh1T_pr-/view), which consists of approximately 9,339 malware samples categorized into 25 distinct families. The second is the Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (BIG 2015) dataset (available at: https://www.kaggle.com/c/malware-classification), which contains around 21,741 malware samples divided into 9 different families.

References

Shi, J. et al. SVM-based malware classification through deep learning method[C]//Fifth International Conference on Signal Processing and Computer Science (SPCS 2024). SPIE, 13442: 49–57. (2025).

Woo, S. et al. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module[C]//Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). : 3–19. (2018).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. : 7132–7141. (2018).

He, K. et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. : 770–778. (2016).

Zhou, J. et al. An integrated CSPPC and BiLSTM framework for malicious URL detection[J]. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 6659 (2025).

Gibert, D. et al. Using convolutional neural networks for classification of malware represented as images[J]. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Techniques. 15, 15–28 (2019).

Agarap, A. F. Towards Building an intelligent anti-malware system: a deep learning approach using support vector machine (SVM) for malware classification[J]. (2017). arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.00318.

Paardekooper, C. et al. Designing deep convolutional neural networks using a genetic algorithm for image-based malware classification[C]//2022 IEEE Congress on evolutionary computation (CEC). IEEE, : 1–8. (2022).

Palma Salas, M. I., De Geus, P. & Botacin, M. Enhancing malware family classification in the Microsoft challenge dataset via transfer learning[C]//Proceedings of the 12th Latin-American Symposium on Dependable and Secure Computing. : 156–163. (2023).

Al-Masri, B. et al. Dual convolutional malware network (DCMN): an Image-Based malware classification using dual convolutional neural networks[J]. Electronics 13 (18), 3607 (2024).

Zhong, F. et al. Malware-on-the-brain: illuminating malware byte codes with images for malware classification[J]. IEEE Trans. Comput. 72 (2), 438–451 (2022).

Chaganti, R., Ravi, V. & Pham, T. D. Image-based malware representation approach with EfficientNet convolutional neural networks for effective malware classification[J]. J. Inform. Secur. Appl. 69, 103306 (2022).

Bao, H. et al. Stories behind Decisions: Towards Interpretable Malware Family Classification with Hierarchical attention[J]144103943 (Computers & Security, 2024).

Ismail, S. J. I., Hendrawan, Rahardjo, B., Juhana, T. & Musashi, Y. MalSSL-Self-Supervised learning for accurate and Label-Efficient malware Classification[J]. IEEE ACCESS. 12, 58823–58835 (2024).

Miao, C. Y., Kou, L., Zhang, J. L. & Dong, G. Z. A lightweight malware detection model based on knowledge Distillation[J]. MATHEMATICS 12 (24), 4009 (2024).

Darem, A. A. A Novel Framework for Windows Malware Detection Using a Deep Learning Approach[J]72461–479 (CMC-COMPUTERS MATERIALS & CONTINUA, 2022). 1.

Lu, Q. K., Zhang, H. W., Kinawi, H. & Niu, D. Self-Attentive models for Real-Time malware Classification[J]. IEEE ACCESS. 10, 95970–95985 (2022).

Kale, G., Bostancı, G. E. & Çelebi, F. V. Evolutionary feature selection for machine learning based malware classification[J]. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 56, 101762 (2024).

Andrade, E. O. et al. Malware classification using word embeddings algorithms and long-short term memory networks[J]. Comput. Intell. 38 (5), 1802–1830 (2022).

Alandjani, G. Securing edge devices: malware classification with Dual-Attention deep Network[J]. Appl. Sci. 14 (11), 4645 (2024).

Gao, X. et al. MaliCage: A packed malware family classification framework based on DNN and GAN[J]. J. Inform. Secur. Appl. 68, 103267 (2022).

Chong, X. et al. Classification of malware families based on efficient-net and 1D-CNN fusion[J]. Electronics 11 (19), 3064 (2022).

Raff, E. et al. Classifying sequences of extreme length with constant memory applied to malware detection[C] //Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 35(11): 9386–9394. (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Deep learning model with sequential features for malware classification[J]. Appl. Sci. 12 (19), 9994 (2022).

Chen, Z. & Ren, X. An efficient boosting-based windows malware family classification system using multi-features fusion[J]. Appl. Sci. 13 (6), 4060 (2023).

Ashawa, M. et al. Enhanced Image-Based malware classification using Transformer-Based convolutional neural networks (CNNs)[J]. Electronics 13 (20), 4081 (2024).

Lin, C. J., Lin, X. Y. & Jhang, J. Y. Malware classification using a Taguchi-based deep learning Network[J]. Sens. Mater. 34 (9), 3569–3580 (2022).

Farfoura, M. E. et al. A Low Complexity ML-Based Methods for Malware Classification[J]. Mater. Continua, 80(3),4833–4857. (2024).

Darem, A. A. A Novel Framework for Windows Malware Detection Using a Deep Learning Approach[J]72461–479 (CMC-COMPUTERS MATERIALS & CONTINUA, 2022). 1.

Ronen, R. et al. Microsoft malware classification challenge[J]. (2018). arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.10135.

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, 2020.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (Fund No. ZDYF2024GXJS034); Hainan Engineering Research Center for Virtual Reality Technology and Systems (Fund No. Qiong fa Gai gao ji [2023] 818); the Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province (Fund No. YSPTZX202036); the Education Department of Hainan Province (Fund No.Hnky2024ZD-24); the Sanya Science and Technology Special Fund (Fund No. 2022KJCX30).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Y., Zhang, K., Zheng, B. et al. GCSA-ResNet: a deep neural network architecture for Malware detection. Sci Rep 15, 24098 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10561-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10561-6