Abstract

Hyperbaric Oxygenation Therapy (HBOT) is a widely used therapeutic option. It involves cycles with administration of 100% oxygen at increased atmospheric pressure to enhance oxygen delivery to tissues. The application of HBOT may affect all organs and tissues including kidneys which may be sensitive to the changes during HBOT. As underlying mechanisms for HBOT, the production of reactive oxygen species including superoxide, antioxidant reactions, increased plasma levels of growth factors and nuclear hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) expression are discussed. Although HBOT is frequently used in man, knowledge about effects of HBOT on kidney function is still lacking in humans. The aim of this pilot study was to monitor changes in renal function parameters, including hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and erythropoietin and employing urinary EV´s to document renal alterations. Test persons (n = 23) enrolled presented healthy renal status and received 10 HBOT sessions. Blood and urine samples were taken at the first, the fifth and the tenth HBOT session. Heart rate decreased during HBOT in male and female test persons which may be due to a stimulation of vagal nerve activity. Serum HIF-1α and erythropoietin values, blood pressure, blood and urine values for renal function parameter except for urine osmolality remained unaffected by HBOT. Urine osmolality together with the trend of renal Na+/K+/2Cl−-cotransporter expression on isolated urinary extracellular vesicles during HBOT significantly increased in both female in male test persons. Most likely, the generation of superoxide may account for the trend in the augmented renal NKCC2 expression and urine osmolality. HIF-1α downstream targets including renal sodium transporter affected by HIF-1α alteration remained unchanged suggesting the relative hypoxia after end of HBOT may not be sufficient. Overall, renal function upon HBOT remained largely unaffected with only minor alterations in urine osmolality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hyperbaric Oxygenation Therapy (HBOT) is a widely used therapeutic option for a variety of clinical conditions that involves administering 100% oxygen at increased atmospheric pressure to enhance oxygen delivery to tissues. Coming from the classic Diving Medicine, HBOT is the first-line therapy in decompression sickness1,2,3,4, but also in barotraumatic or iatrogenic arterial gas embolism5,6,7, as well as in severe carbon monoxide-poisoning2,8,9,10,11. In addition, HBOT is a well-recognized additional therapeutic option in severe mixed or anaerobic infections, such as necrotizing soft tissue infections and gas gangrene12,13, in problematic wound therapy, such as late radiation tissue injury14, some forms of osteomyelitis15,16 or diabetic foot ulcera17,18 and in sudden sensorineural hearing loss or tinnitus19,20,21. Furthermore, there is growing evidence, that HBOT elicits anti-inflammatory22,23,24 and/or immunomodulatory effects25,26,27, which may offer new therapeutic options in diseases with chronic inflammation and/or inappropriate immunologic status.

HBOT comprises cycles of extreme hyperoxia and relative hypoxia after the end of an HBOT-session. The application of HBOT may affect nearly all organs and tissues and cause specific and measurable changes in laboratory parameters. HBOT with oxygen partial pressures (pO2) up to 300 kPa leads to a significant increase in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), antioxidant reactions28, increased plasma levels of growth factors29 and nuclear hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) expression30, which all may affect body organ functions.

The kidneys receive approximately 20% of the cardiac output. At the same time, the kidneys present a heterogeneity in blood perfusion and oxygen consumption and may thus react in a sensitive way to the changes between extreme hyperoxia and relative hypoxia during HBOT. The effects of HBOT on renal function was studied in a rat model showing no alterations during 5 days HBOT treatment31. However, although HBOT is frequently used in man, information about the effects of HBOT on kidney function is still lacking in humans. The measurement of renal function parameters can be easily done in clinical routine. Extracellular vesicles (EV´s) excreted in the urine are predominantly derived from epithelial cells in the genitourinary system32. The exploration of urinary EV´s is a noninvasive method and may be used for diagnosis and prognosis of urogenital diseases since EV´s still keep the properties of the cells from which they were formed.

Thus, it was the aim of this pilot study to monitor changes in renal function parameters, including HIF-1α and erythropoietin and to use urinary EV´s to document renal alterations before and after a set of therapeutic HBOT-sessions as judged by changes in surface characteristics of urinary EVs and the abundance of renal sodium transporters in routine HBOT-treatment.

Results

Patient enrollment

In total n = 23 test persons were enrolled in this study with n = 12 male and n = 11 female test persons. The study design is illustrated in Fig. 1 showing the days of treatment performed including two days break in between.

Cardiovascular and renal function data

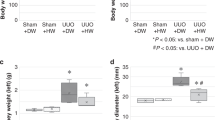

Blood pressure of the test persons remained unaltered during HBOT (Fig. 2A). Heart rate of male and female test persons decreased during their stay in the hyperbaric oxygen chamber of HBOT (Fig. 2B). Hemoglobin values also decreased during the two weeks of HBOT, when comparing the first blood sampling with the tenth blood sampling of all test persons (Fig. 3A). This reduction most probably is due to a dilution effect during HBOT and not a consequence of HBO treatment. Serum creatinine, cystatin C, HIF-1α and erythropoietin (EPO) remained unaffected (Fig. 3B–E).

Blood pressure and heart frequency of all test persons during HBOT. (A) Blood pressure and (B) heart frequency in beats per minutes (bpm) is presented. All values are mean ± SEM, n = 15 with n = 10 male test persons and n = 5 female test persons. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0,001 were considered significant.

Analysis of urine parameter revealed that urine osmolality significantly increased over the time of HBOT comparing all test persons, especially in male test persons the trend was clearly visible (Fig. 4A). The urine excretion of sodium, potassium and calcium normalized to creatinine excretion respectively, remained unaltered during the days of HBOT (Fig. 4B–D). Analysis of urine parameter obtained from control test persons remained unaltered (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Na+/K+/2Cl–cotransporter (NKCC2) abundance increases on the surface of urinary ev´s

Isolated urinary EV´s showed the expected size and double membrane as judged by electron microscopy (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, EV samples were controlled for proper and clean EV isolation by electron microscopy. We also determined EV size distribution by Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), showing similar distribution between HBOT test persons and control test persons (Fig. 5B). HBOT with its cycles of extreme hyperoxia and relative hypoxia after the end of each HBOT-session may impact renal sodium transporter expression as demonstrated earlier33, therefore we tested for the abundance of renal sodium transporters and directly tested for HIF-1α downstream targets on EVs. NKCC2 abundance normalized to CD9 abundance increased over the time in HBO treated test persons compared to control test persons with a significant difference in trend line during the time (Fig. 5C and D).

NKCC2 expression increases on urinary extracellular vesicles (EV´s). (A) Electron microscopy images of isolated EV showing the typical double membrane (arrow heads). (B) EV size distribution by Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) analysis showing similar distribution between HBOT test persons and control test persons. (C and D) Representative western blots (C) and semiquantitative densitometric evaluation (D) of NKCC2 and CD9 from isolated EV´s of control test persons (CTL) and HBOT test persons (HBOT). Values are mean ± SEM, n = 3–4. The trend was calculated by linear regression analysis followed by slope comparation analysis, *P < 0.05 was considered significant. Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Other sodium transporters such as sodium hydrogen exchanger-3 (NHE3), Na+/Cl−-cotransporter (NCC), α- and γ- subunit of the epithelial sodium channel (αENaC and γENaC) remained unchanged. Similar downstream targets of HIF-1α such as glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) and hexokinase-2 remained unaltered, too. All western blots and parameter analyzed are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2 and original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Discussion

The kidney senses systemic oxygen, regulates erythropoiesis and hence oxygen content by hypoxia-inducible erythropoietin (EPO) expression. The characteristic of HBOT is the combination of delivering extremely high pO2 to the tissues, combined with in contrast to that short relative hypoxic phases during (10 min of ambient air during air-break inside an HBOT-session) and between HBOT-sessions on following days. These fluctuations in tissue oxygenation may affect renal function, which we aimed to address here.

In the presented pilot study over a period of 10 HBOT-sessions we observed in our test persons a reduction in heart rate during each HBOT, a slightly decline in hemoglobin, an increased urine osmolality together with increased NKCC2 surface EV over ten HBOT-sessions.

The observed reduction in heart rate was described previously34. Reduced heart frequency together with increased blood pressure during HBOT were also described as rare potential serious consequences of HBOT35. Therefore, authors suggested targeted cardiac investigation prior to HBOT to diagnose patients with high-risk features. HBOT was shown to stimulate vagal nerve activity with sinus bradycardia34. As underlying mechanism of the vagal nerve activation, a stimulation of neurons in the vagal dorsal motor nucleus and nucleus solitarius was identified.

We further observed slightly reduced hemoglobin values over time, but only, when the first blood sample, which was taken before the first HBOT, was compared to the other samples, which were all taken after the HBOT sessions. One factor, that may have contributed to some decrease in hemoglobin is the overall amount of blood taken for clinical analysis from the patients, which was in sum about 50–70 ml (see Fig. 1). And, since the hemoglobin values of the blood samples taken after the HBOT sessions differed not significantly, the 500 ml of fluid intake, that was provided during each therapy session, may have caused an additional plasma dilution effect. This fits to current literature, since alterations in hemoglobin during an HBOT series have not been described yet. We also determined serum HIF-1α and erythropoietin levels in our test persons throughout the two weeks of HBOT. HIF-1α and EPO values remained in a normal physiological range with only minor alterations. During hypoxia, HIF-1α expression strongly increases in renal epithelial cells36,37, whereas EPO is mainly produced and released by renal cortical interstitial fibroblast in a HIF-2α -dependent manner38,39. These results suggest that the fluctuation in tissue oxygenation during HBOT is not sufficient to induce tissue hypoxia with subsequent HIF-1α stabilization and EPO release that is detectable in serum. Although, HIF-1α alterations during HBOT were described in humans and in animal models40,41 the difference to our study may be related to the duration of HBOT. In our study, the HBOT of the enrolled patients was shorter (two cycles of 5 days) than other studies of HBOT in human21,41 and may not have led to significant HIF-1/2α stabilization yet.

The analysis of the urine parameters revealed significantly increased urine osmolality which in general is affected by the amount of sodium excreted. In addition, hypoxia was shown to affect renal sodium transporter expression33,42 we sought to address their expression levels by analyzing excreted urinary vesicles. In congruence with increased osmolality, we observed higher NKCC2 expression during HBOT. Since we did not find an indication of tissue hypoxia in our study, another explanation for the higher NKCC2 expression could be the HBOT-induced superoxide generation, which we have shown to occur in HBOT recently43. Thus, superoxide was shown to play a role in renal sodium transport44 and was nicely demonstrated to enhance surface NKCC2 expression in the thick ascending limb possibly explaining the rise in urine osmolality over time during HBOT42. Other renal sodium transporter such as NHE-3, NCC, αENaC and γENaC remained unaltered. Those transporters were shown to be affected by manipulation of renal HIF-1α expression33, suggesting that the relative hypoxia occurring during (the 10 min air-breaks every 30 min) and between the HBOT-sessions may not be sufficient to provoke changes. This is also in agreement with HIF-1α and erythropoietin serum levels which remained unaltered. In addition, we tested partially for GLUT-1 and hexokinase-2 expression on the urine EV fractions. Both proteins are known downstream targets of HIF-1α. Again, no alterations or even trends were observed supporting the idea that only very low or short occurrence of relative hypoxia may take place after HBOT.

The limitation of our study is the n-number of test persons enrolled and the duration of HBOT. Since the enrolled patients had to be free of any renal dysfunction, our study-cohort consisted of patients with different forms of subacute hearing problems, where a therapeutic attempt with HBO is indicated, but with a limited number of HBO-sessions, normally about ten. Future studies with longer duration of HBOT would be helpful to demonstrate whether NKCC2 augmentation persists.

Conclusion

HBOT in humans affects heart frequency during the HBOT-session and over time it may increase renal NKCC2 expression and urine osmolality. The short phases of relative hypoxia during HBOT and the return of pO2 from hyperoxia to normoxia after HBOT may have only initiated effects to a minor extent in this study without altering HIF-1α, EPO or HIF-1α downstream targets. Overall, renal function remained largely unaffected.

Methods

Study design

Patients enrolled in this study were diagnosed for sudden sensorineural hearing loss or tinnitus, they showed a healthy renal status and presented themselves for hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). In total n = 23 test persons, ageing between 25 and 70 years, were enrolled in this study with n = 12 male and n = 11 female test persons. Among the test persons n = 10 male and n = 5 female test persons underwent HBOT and n = 2 male and n = 6 female test persons followed the same protocol without receiving HBOT. 10 HBOT sessions were applied on five days a week with weekend-break, following a regular clinical schedule (100% O2 at 240 kPa for 90 min with two 10 min air-breaks, over all 130 min). Each HBOT session started at the same time in the morning.

Blood samples were taken before and after the first, after the fifth and after the tenth HBOT session. Urine samples were collected before and after the first, the fifth and the tenth HBO treatment. Blood pressure and heart rate were monitored every 15 min during the 130 min stay inside the hyperbaric oxygenation chamber of the first, the fifth and the tenth HBO treatment. During HBOT patients received 500 ml drinking water.

This study (named RENOX) was approved by the local Ethic committee of the medical association Aachen, Germany under the number 2,021,469. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Ethic committee. All participants and/or their legal guardians provided written informed consent.

Blood and urine collection and analysis

Blood sample analysis was performed in a routine medical laboratory (MVZ Stein, Mönchengladbach, Germany). Hemoglobulin (Hb in g/dl) was determined by photometry, cystatine C (cysC in mg/l) by turbidometry, creatinine by Jaffé photometry, HIF-1α were determined by ELISA (A313500, VWR) and erythropoietin was measured in the medical laboratory (MVZ Stein, Mönchengladbach, Germany). Urine samples were taken before and after the first, the fifth and the tenth HBOT and treated with protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, 0.1 mM, Thermofisher, Germany). Electrolyte concentration in urine and serum samples were determined by flame photometry (EFOX 5053, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and urine osmolality by algoskopy (Osmomat 3000, Gonotec, Berlin, Germany). Serum and urine creatinine were determined by colorimetric quantitative determination of creatinine (PAP test, LT-CR0106, Labor & Technik, Berlin, Germany).

Urinary extracellular vesicle isolation

Urinary extracellular vesicles (EV) were isolated according the improved protocol using the differential ultracentrifugation approach including DTT-mediated recovery of Tamm Horsfall protein (THP)-entrapped EVs and alkaline washing45. All urine samples of one patient (100 ml) were thawed at 4 °C and normalized to the lowest creatinine value received per sample of the patient. Samples with higher creatinine value were adapted to equal volume using PBS. Normalized and equalized urine samples were transferred to 50 ml falcon tubes (Sarstedt, Germany) and centrifuged at 20,000 g (Minifuge 1-SR, Kendro, Germany) for 30 min to remove cells and cell debris. The supernatant was kept on ice. The resulting pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer containing 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 with DTT at a final concentration of 200 mg/ml DTT and after incubation for 5 min, centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was pooled with the first supernatant and centrifuged at 175,000 g (L7-65, Beckman) for 2 h. Resulting pellet was resuspended in 5 ml alkaline solution (50 mM Na2Co3, pH = 11) and was passed through a 0.22 µM PES syringe filter (Millipore SLGP033RS) to remove large particles. The filter was rinsed with an additional 5 ml of alkaline solution and total filtrate was ultracentrifuged at 175,000 g for 2 h and final pellet resuspended in 200 µl PBS and used for western blotting.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Aliquots of the resuspended EV pellets (P4) in PBS were further diluted in PBS and a small volume of the diluted EVs were transferred to negative-glow discharged continuous carbon grids (Science Service, Munich, Germany) and stained with a half‐saturated solution of uranyl acetate. The images were generated using a JEOL‐1400‐Plus‐TEM (JEOL Germany, München) with integrated TemCam‐F416 camera (TVIPS, München).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

The EV size distribution and concentration of the particles in the resuspended EV pellet were determined via NTA with a NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern, Panalytical, Malvern, UK) using NanoSight software version 3.40 (Malvern). Samples were diluted in PBS to achieve a particle concentration within the optimal range for analysis reported by the manufacturer.

SDS-Page and Western blot

Proteins were solubilized and SDS gel electrophoresis was performed on 10% polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoretic transfer of the proteins to nitrocellulose membranes, equity in protein loading and blotting was verified by membrane staining using 0.1% Ponceau red. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies (s. list) and then exposed to HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). Immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence using Immobilon Western HRP substrate (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) in combination with the chemiluminescence imaging system Fusion SL (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) and further analyzed using ImageJ software.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-NHE3 (Novus Biologicals, NBP1-82574), guinea anti-NKCC2 (gift. S. Bachmann), sheep anti-NCC (S961B, University of Dundee), rabbit anti-αENaC (StressMarq, SPC-403D), rabbit anti-γENaC (StressMarq, SPC-405D), rabbit anti-GLUT1 (Merck Millipore, 07-1401), rabbit anti-NHE3 (NBP1-8257 Novus), anti-CD9 (invitrogen, MA5-31980), and rabbit anti-hexokinase-2 (Poteintech, 22029-1-AP).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Prism). Data are provided as arithmetic means ± SEM with n representing the number of used samples. To test statistical significance, repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test and linear regression analysis followed by slope comparation analysis was performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Materials and Methods, Results, and/or Supplementary Material of this article.

References

Vann, R. D., Butler, F. K., Mitchell, S. J. & Moon, R. E. Decompression illness. Lancet 377, 153–164 (2011).

Sen, S. & Sen, S. Therapeutic effects of hyperbaric oxygen: integrated review. Med. Gas Res. 11, 30–33 (2021).

Moon, R. E. & Mitchell, S. J. Hyperbaric oxygen for decompression sickness. Undersea Hyperb Med. 48, 195–203 (2021).

Moon, R. E. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment for decompression sickness. Undersea Hyperb Med. 41, 151–157 (2014).

Hellinger, L., Keppler, A. M., Schoeppenthau, H., Perras, J. & Bender, R. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for iatrogenic arterial gas embolism after CT-guided lung biopsy: A case report. Anaesthesist 68, 456–460 (2019).

Fakkert, R. A. et al. Early hyperbaric oxygen therapy is associated with favorable outcome in patients with iatrogenic cerebral arterial gas embolism: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Care. 27, 282 (2023).

Tekle, W. G. et al. Factors associated with favorable response to hyperbaric oxygen therapy among patients presenting with iatrogenic cerebral arterial gas embolism. Neurocrit Care. 18, 228–233 (2013).

Chenoweth, J. A., Albertson, T. E. & Greer, M. R. Carbon monoxide poisoning. Crit. Care Clin. 37, 657–672 (2021).

Freytag, D. L., Schiefer, J. L., Beier, J. P. & Grieb, G. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment in carbon monoxide poisoning - Does it really matter? Burns 49, 1783–1787 (2023).

Eichhorn, L., Thudium, M. & Juttner, B. The diagnosis and treatment of carbon monoxide poisoning. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 115, 863–870 (2018).

Ning, K. et al. Neurocognitive sequelae after carbon monoxide poisoning and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Med. Gas Res. 10, 30–36 (2020).

Stevens, D. L. & Bryant, A. E. Necrotizing Soft-Tissue infections. N Engl. J. Med. 377, 2253–2265 (2017).

Huang, C. et al. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on the clinical outcomes of necrotizing soft tissue infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 18, 23 (2023).

Lin, Z. C. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for late radiation tissue injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, CD005005 (2023).

Simon, M. et al. Skull base osteomyelitis: HBO as a therapeutic concept effects on clinical and radiological results. Eur Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 282, 1835-1842 (2025)

Gomes, P. M. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in malignant otitis externa: a retrospective analysis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 281, 5153–5157 (2024).

Sharma, R., Sharma, S. K., Mudgal, S. K., Jelly, P. & Thakur, K. Efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot ulcer, a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Sci. Rep. 11, 2189 (2021).

Apolo-Arenas, M. D. et al. Use of the Hyperbaric Chamber Versus Conventional Treatment for the Prevention of Amputation in Chronic Diabetic Foot and the Influence on Fitting and Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Int J Vasc Med 2024, 8450783 (2024).

Oya, M., Tadano, Y., Takihata, Y., Ikomi, F. & Tokunaga, T. Utility of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for acute acoustic trauma: 20 years’ experience at the Japan maritime Self-Defense force undersea medical center. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 23, e408–e414 (2019).

Huang, C., Tan, G., Xiao, J. & Wang, G. Efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen on idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss and its correlation with treatment course: prospective clinical research. Audiol. Neurootol. 26, 479–486 (2021).

Wang, H. H. et al. Effect of the Timing of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy on the Prognosis of Patients with Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Biomedicines 11 (2023).

Aricigil, M. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of hyperbaric oxygen on irradiated laryngeal tissues. Braz J. Otorhinolaryngol. 84, 206–211 (2018).

Sunshine, M. D. et al. Oxygen therapy attenuates neuroinflammation after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 20, 303 (2023).

De Wolde, S. D., Hulskes, R. H., Weenink, R. P., Hollmann, M. W. & Van Hulst, R. A. The Effects of Hyperbaric Oxygenation on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Angiogenesis. Biomolecules 11 (2021).

Kjellberg, A. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as an Immunomodulatory intervention in COVID-19-induced ARDS: exploring clinical outcomes and transcriptomic signatures in a randomised controlled trial. Pulm Pharmacol. Ther. 87, 102330 (2024).

Kjellberg, A. et al. Comparing the Blood Response to Hyperbaric Oxygen with High-Intensity Interval Training-A Crossover Study in Healthy Volunteers. Antioxidants (Basel) 12 (2023).

Tillmans, F. et al. Effect of hyperoxia on the immune status of oxygen divers and endurance athletes. Free Radic Res. 53, 522–534 (2019).

Leveque, C. et al. Oxidative stress response kinetics after 60 minutes at different (1.4 ATA and 2.5 ATA) hyperbaric hyperoxia exposures. Int J. Mol. Sci 24(15):12361 (2023)

Capo, X. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy reduces oxidative stress and inflammation, and increases growth factors favouring the healing process of diabetic wounds. Int J. Mol. Sci 24(8):7040 (2023).

Song, K. X. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves the effect of keloid surgery and radiotherapy by reducing the recurrence rate. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 19, 853–862 (2018).

Berkovitch, M., Tsadik, R., Kozer, E. & Abu-Kishk, I. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on kidneys in a rat model. ScientificWorldJournal 2014, 105069 (2014).

Blijdorp, C. J., Burger, D., Llorente, A., Martens-Uzunova, E. S. & Erdbrugger, U. Extracellular vesicles as novel players in kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 33, 467–471 (2022).

Dizin, E. et al. Activation of the Hypoxia-Inducible factor pathway inhibits epithelial sodium Channel-Mediated sodium transport in collecting duct principal cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 3130–3145 (2021).

Singh, B., Bhyan, P. & Cooper, J. S. Hyperbaric cardiovascular effects. In StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL) Ineligible Companies. Disclosure: Poonam Bhyan Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies (Jeffrey Cooper declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies, 2025).

Brenna, C. T. et al. The role of routine cardiac investigations before hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Diving Hyperb Med. 54, 120–126 (2024).

Haase, V. H. Hypoxia-inducible factors in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 291, F271–281 (2006).

Kunke, M. et al. Targeted deletion of von-Hippel-Lindau in the proximal tubule conditions the kidney against early diabetic kidney disease. Cell. Death Dis. 14, 562 (2023).

Broeker, K. A. E. et al. Different subpopulations of kidney interstitial cells produce erythropoietin and factors supporting tissue oxygenation in response to hypoxia in vivo. Kidney Int. 98, 918–931 (2020).

Kobayashi, H. et al. Distinct subpopulations of FOXD1 stroma-derived cells regulate renal erythropoietin. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 1926–1938 (2016).

Sunkari, V. G. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy activates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), which contributes to improved wound healing in diabetic mice. Wound Repair. Regen. 23, 98–103 (2015).

Salmon-Gonzalez, Z. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy does not have a negative impact on bone signaling pathways in humans. Healthcare (Basel) 9(12):1714 (2021).

Haque, M. Z. & Ortiz, P. A. Superoxide increases surface NKCC2 in the rat Thick ascending limbs via PKC. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 317, F99–F106 (2019).

Groger, M. et al. DNA damage after long-term repetitive hyperbaric oxygen exposure. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 106, 311–315 (2009).

Juncos, R. & Garvin, J. L. Superoxide enhances Na-K-2Cl cotransporter activity in the Thick ascending limb. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 288, F982–987 (2005).

Correll, V. L. et al. Optimization of small extracellular vesicle isolation from expressed prostatic secretions in urine for in-depth proteomic analysis. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 11, e12184 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Lettau, A. Gerneth, M. Lemmer and S. Luick for excellent technical assistance, I. Nünning for graphical support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. FT was supported by the DFG (CRC 877) and Helmut Horten Foundation. Study was supported by a funding program of the German Society of Diving- and Hyperbaric Medicine (GTÜM e.V.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK, YS, ML performed experiments. YS, AK, FT analyzed data. AK, MM, TK and FT were responsible for conceptualization, interpretation of data, supervision, writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors read, revised and authorized the manuscript before submission. FT is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanowski, S., Shen, Y., Klein, T. et al. Impact of hyperbaric oxygenation therapy (HBOT) on renal function in human. Sci Rep 15, 25143 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10569-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10569-y