Abstract

The brown bullhead is a fish native to North America that became an invasive species after being introduced into the waters of Europe and other regions. Studies on its sexual cycle and fecundity were conducted on a population from an oxbow lake of the central Vistula River in Poland. The fish ranged in age from 1 + to 9+. The average body length (SL) was 14.4 ± 3.4 cm. Individuals as young as 1 + were already mature. Females lay eggs multiple times from mid-April to mid-June, with absolute fecundity averaging 3227 oocytes and relative fecundity at 46 oocytes g−1. The highest mean GSI of 1.9 during spawning was recorded in June. The reproductive tract of males takes the shape of lobes and consists of a paired cranial region formed by testes and a caudal region of undefined function. In males, semi-cystic spermatogenesis occurs, with secondary spermatocytes leaving cysts. Males overwinter with tubules filled with spermatids and initiate spermatozoa formation. The highest average GSI of 0.49 was recorded in early April. The brown bullhead observed in the new habitat was characterized by multiple egg laying, earlier maturation of individuals, and spawning in the earlier part of the calendar year, i.e. mid-April to mid-June, compared to its native habitat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) is native to North America. In Europe, it is an invasive species found in countries such as France, Germany, England, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Poland, Spain, Ukraine, Belarus, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Finland1,2,3,4,5. Additionally, it has been an invasive species in New Zealand since the 1980s6.

It was brought to Poland to enhance the ichthyofauna in the second half of the 19th century, with the largest expansion occurring after World War II7. Currently, the species is widely distributed in Poland as a result of natural expansion. It is highly tolerant of pollution and oxygen deficits and thrives in a wide range of temperatures (0–36oC)8,9,10,11. In Central Europe, it is classified as one of the invasive species. It consumes the eggs of other fish, often becoming the dominant or sole species in the rivers it inhabits, making it an ecological and economic threat7,12. This is particularly significant, especially since the intensive invasion of this species in Polish waters has been observed in recent years13,14.

In North America, the native range of the brown billhead’s occurrence, the spawning period for this species depends on the region and occurs from late May to early June, from June to mid-July, or from July to August, with spawning in the southern areas possibly continuing through September at water temperatures of 18–25 °C (14–29 °C)8,9,15,16,17. Generally, females and males breed with only one mate each season; however, reproductive activity may vary depending on conditions16. In the southern United States, they may spawn more than once in a year8. Fish mature at ages 2+−3+, with a minimum size of 17.8 cm8,9,15,16,17,18. Oocyte diameter is about 3 mm, with fecundity ranging from 1,000 to 5,000 (13,000)8,9. The developing eggs are guarded by both parents, although the male shows a stronger instinct for care16. This guardianship continues until the offspring begin foraging independently19. The sexual cycle of males and fluctuations in serum levels of gonadal steroid hormones have been described in the area of its native occurrence (Lake Ontario)15,20. However, no data on the sexual cycle of this invasive species is available for populations living in European waters. Understanding the life cycle and fecundity is important to estimate the potential expansion and density increase of European populations and will allow for appropriate control measures to be taken against this expansive species.

The aim of this study was to describe the sexual cycle and fecundity of brown bullhead populations in Central Poland (Central Vistula River basin), based on histological and stereoscopic analyses of gonads.

Materials and methods

Fish sampling and location description

Brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus Lesueur, 1819) (synonym Ictalurus nebulosus) (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae) were caught in oxbow lake of the Vistula river, located in the village of Józefów near Warsaw (Poland) of coordinates 52.13815° N, 21.18593° E (Fig. 1). Harvesting was conducted using net fishing gear (trawls) by licensed fishermen every 30 days from January to December 2023, while during the spawning period, fishing occurred 2–3 times (from April to June). A total of 489 fish were caught (Table 1). The research focused on dead fish, which were obtained from a licensed fisherman. The fish were killed by a licensed fisherman in accordance with the euthanasia rules established in Poland, who is authorized to perform euthanasia. The brown bullhead is classified as an invasive species that must be removed from the environment in Poland based on the Act Dz.U. 2021 item 1718, in accordance with European Union law.

A small laminar water flow was observed in the study reservoir with a muddy bottom. The depth was approximately 1–2 m. The dominant fish species is brown bullhead, with roach (Rutilus rutilus) and perch (Perca fluviatilis) as subdominants. Additionally, the following fish species can be found in the reservoir: rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), pike (Esox Lucius), carp (Cyprinus carpio), tench (Tinca tinca), silver carp (Carassius gibelio), white bream (Blicca bjoerkna), bream (Abramis brama), stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), bleak (Alburnus alburnus), sunfish (Leucaspius delineatus), and occasionally catfish (Silurus glanis) and eel (Anguilla anguilla). The dominant submerged vegetation is mainly Canadian waterweed (Elodea canadensis) and hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum), as well as emergent vegetation, primarily represented by common reed (Phragmites australis). The reservoir is situated in the Natura 2000 area “Middle Vistula Valley” (PLB140004) and within the Warsaw Protected Landscape Area. In addition to fish sampling, water measurements were taken directly in the field. Water temperature (°C) was measured every seven days from January to December 2023 at an approximate depth of 1 m below the water surface, using a multiparameter sensor HQD30 produced by Hach (Düsseldorf, Germany).

Location of the study area in central Vistula, Poland (coordinates 52.13815° N, 21.18593° E). The map was created in Adobe Photoshop based on map from the Polish Waters website (https://wody.isok.gov.pl/imap_kzgw/?gpmap=gpPDF).

Analysis of fish size, age, gonads, and fertility

In the laboratory, fish lengths were measured: total length (TL) and standard length (SL) were recorded with an accuracy of 0.1 mm, and the fish were weighed on an electronic scale (Radwag) with an accuracy of 0.1 g. The age of the fish was determined based on the year rings on otoliths following a method commonly used for catfish21,22. Preparing the otoliths for reading involved browning each otolith on a hot plate to enhance the readability of the rings, grinding each otolith with wet 400-grit sandpaper, and polishing the otolith with 600-grit sandpaper to expose the nucleus. The age of the fish was then determined from the visible rings on the otolith prepared in this manner, using a microscope with side illumination (reflecting light at different angles)23.

Gonads were dissected and fixed in 10% formic formaldehyde (females), Bouin’s solution, or buffered formalin (males). Gonads were weighed to the nearest 0.1 mg. Between April and June, the right and left gonads of females were weighed separately. The Fulton condition index (CF = gonad mass [g] x length−3 [cm] x 100%) and gonadosomatic index (GSI = gonad mass [g] x full fish body mass−1 [g] x 100%) were calculated24. Histological preparations were made using standard paraffin techniques. Section 5 μm thick were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (females), Heidenhain’s iron hematoxylin (males), and the alcian blue PAS kit (males). Between 50 and 80 histological sections of gonads were placed on one microscope slide. Histological sections were analyzed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i light microscope, and photographic documentation was recorded with NIS Elements 3.20 software and a Nikon DS-5Mc-U2 digital camera featuring a resolution of 5 million pixels. The maturity of gonads was described using a 5-stage classification published by Grier25. The finding of multiple egg laying was based on histological analysis of the ovary. The presence of postovulatory follicles and numerous ripening oocytes in the gonads at the beginning of the spawning period, indicates the potential for laying another batch of eggs.

The fixed left gonads of all females caught from April to June were immersed in DMSO and stored in a freezer. From the weighed fragment of the left gonad observed with a Discovery.V12 Zeiss stereoscopic microscope, all oocytes from the gonad were separated into five size classes: group 1 - oocytes with completed vitellogenesis, spawning oocytes (fat fused with yolk), group 2 - oocytes completing vitellogenesis (oocytes with yolk), group 3 - oocytes in vitellogenesis (oocytes with fat droplets), group 4 - oocytes in advanced previtellogenesis, and group 5 - oocytes in early previtellogenesis, primary growth (stock for the next season). In each class, oocytes were counted, and the diameter of 30–50 oocytes from each class was measured. The oocyte diameter was calculated from the measurements of the longest and shortest diameters of the mid cross section of the oocyte11 with an accuracy of 0.01 μm. All oocytes from each size group were then counted for both gonads. Based on the number of counted oocytes from classes 1–4, potential and relative fertility (number of oocytes per gram of fish) were calculated. The smallest oocytes from group 5 were not included in the fecundity, as these oocytes will not mature in the current season26.

Statistical analysis

Distribution of variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, while homogeneity of variance was examined with the Levene test27. The Kruskal-Wallis test compared the temperature distribution, GSI, fecundity, and sizes of oocytes across different stages. A logarithmic transformation of the fertility data was applied. The significance of differences in the number of females and males was analyzed with the chi-square test. All statistical analyses were conducted at a significance level of 0.05 using Statistica v.13 software (StatSoft, Inc.).

Results

Measurements of environmental parameters

The average monthly water temperature at the catchment site is shown in Fig. 2. The temperature during the spawning period (determined by the presence of class 5 of female gonad development) in the study region ranged from 15 to 21 °C.

Sex ratio, age, length, weight, condition factor (CF), gonad weight and gonadosomatic index (GSI) of fish

The sex ratio of females to males for the caught brown bullhead was 1:1. The ages of the fish ranged from 1 + to 9+. Fish sizes ranged from 8.6 to 30.5 cm for total length (TL), from 7.2 to 25.5 cm for standard length (SL), and fresh weights ranged from 6.7 to 418.3 g, respectively. The average Fulton condition index was 1.8 (0.9–2.9).

Females

Females ranged in age from 1 + to 7+. The largest group of females was 3+, which accounted for 34% of all females. The mean length (SL ± SD) was 14.3 ± 2.97 cm; the average weight was 59.1 ± 36.55 g; and the mean CF was 1.8 ± 0.31 (Table 2). The mean GSI of brown bullhead females each month ranged from 0.2 in July to 1.9 in June (Fig. 3). The average GSI during the spawning period was 1.9 ± 2.59. Since spawning occurred in portions among individual females, varying groups were found with different GSI. The GSI of females during egg laying was 6.4 ± 6.79 (1.7–8.9), and post-egg laying was 1.0 ± 0.25 (0.2–1.4). Most of the pre-spawning and spawning females had GSIs ranging from 1.1 to 1.9, with only 6 females between 3.4 and 8.9. The highest GSI (8.9) was that of a 4+, SL 17.2 cm female caught in June and was probably a female just before spawning.

Males

Males ranged in age from 1 + to 9+. Individuals of this sex were longer than females (p˂0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test); the mean standard length (SL) of males was 14.7 ± 3.76 cm, with a weight of 74.2 ± 58.80 g and a condition factor (CF) of 1.8 ± 0.29 (Table 2). The gonadosomatic index varies throughout the year (p < 0.05, ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis test). After spawning from July to September, the mean GSI value ranged from 0.09 to 0.13. During autumn, winter, and early spring, it increased and fluctuated around 0.3. In April, at the beginning of the breeding season, GSI reached 0.5 and then dropped to 0.2 in June (Fig. 3).

Reproductive cycle

Females

In March, all females had gonads containing oocytes in previtellogenesis (primary growth) and in advanced vitellogenesis (secondary growth) (Fig. 4a). In April, the greatest variation was observed in the histological structure of the gonads of brown bullhead females. The first group of females had gonads filled with oocytes in advanced vitellogenesis, preparing to lay eggs. The second group in mid-April consisted of females with spawning gonads, which revealed oocytes with fused yolk, as well as degenerated non-spawning oocytes and ruptured follicles, likely after laying the first batch of eggs (Fig. 4b). A third of the females exhibited gonads with single final oocyte maturation among numerous primary growth oocytes (previtellogenesis), which are likely to mature in the next season (Fig. 4c). At the beginning of May, the gonads resembled those of April females. However, by the end of May, more degenerating oocytes appeared in the gonads of some females, occupying around 1/4 to 1/3 of the histological section of the gonad. In the first half of June, the last spawning gonads were observed, and the rubbed gonads contained previtellogenic oocytes for the next season, oocytes beginning vitellogenesis, and degenerating oocytes. By the end of June, July, and August, all gonads contained oocytes in the initial stage of vitellogenesis and ruptured follicles (Fig. 5). In August, large degenerating oocytes were still present in the gonads (Fig. 4d). From September to February, the number of oocytes in previtellogenesis and vitellogenesis in the gonads gradually increased. Degenerating, mostly single, oocytes were found in the gonads of females from April to November. The peak number of degenerating oocytes occurred in the gonads from April to August (Fig. 4e) and also in November, where degeneration was observed in 60% of females (Fig. 4f). The histological image of the gonads indicates that spawning among the brown bullhead females we studied began in mid-April and ended in mid-June. After spawning, the gonads quickly rebuild and secondary growth is observed from July, Fig. 5. The average age for reaching sexual maturity in our case was 3.1 years, with a standard length of 13.3 cm. The smallest female to enter spawning was 1 + years old, with a standard length of 9.2 cm.

Female gonad of the brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) inhabiting the oxbow lake of the Vistula River, Poland; A: in early vitellogenesis with oocytes in previtellogenesis (P) and vitellogenesis (V), March. Scale bar 100 μm; B: spawning gonad with mature oocytes and post-ovulatory follicles (star), April. Scale bar 100 μm; C: developing gonad containing oocytes in previtellogenesis (P), vitellogenesis (V), and degenerating oocytes (D), May. Scale bar 200 μm; D: post-spawning gonad with degenerating oocytes (D) and post-ovulatory follicles (star), June. Scale bar 100 μm; E: degenerating oocytes (D) in the gonad preparing for the next season with oocytes in previtellogenesis (P) and vitellogenesis (V), August. Scale bar 100 μm; F: single oocytes in vitellogenesis (V) between oocytes in previtellogenesis (P) and degenerating oocytes (D), November. Scale bar 200 μm.

Fecundity and size of oocytes

Five groups of oocytes were identified in brown bullhead gonads from March to September. The largest oocytes (group 1) had a diameter of 2247.1 μm (range 1805.0-3079.0) and the smallest 182.1 μm (range 83.5-245.3) (Table 3). The absolute fecundity of brown bullhead (oocytes of groups 1–4) averaged 3227 and the relative fecundity 46 oocytes g−1 (Table 4).

Fertility increased with the length of the fish (Fig. 6a) and their age (Fig. 6b).

Males

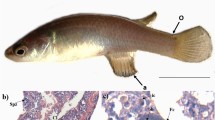

The reproductive tract of the brown bullhead consists of an paired generative part (testes, cranial region) making up about 4/5 of the length of the reproductive tract, which transitions into the caudal region, representing about 1/5 of its length. The testes are shaped like thin, wavy, ribbon-like branches or lobes. The caudal part is similarly lobed, with slightly smaller fringes (Fig. 7). Brown bullhead gonads are of the anastomosing tubular, unrestricted type, and exhibit semi-cystic spermatogenesis. The caudal region is comprised of tubules lined with epithelial cells that change from cuboidal to columnar during the reproductive cycle.

The reproductive system of the male brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) consists of a paired structure shaped like lobes, comprising 4/5 of the cranial region (A) (testes, germinal region) and 1/5 of the caudal region (B), connected terminally. On the left, the reproductive system is shown during the spawning period within the abdominal cavity of dissected fish. On the right, the dissected system is represented in the post-spawning period. (taking the photo A. Kompowska, editing figure K. Dziewulska). Scale bar: 10 mm.

Histological analysis showed that males overwinter with gonads whose tubules were filled with spermatids. The spermatids filled the entire lumen of the tubule without being enclosed in cysts. Few reserved type A spermatogonia were located on the tubule wall (class 4, late maturation class, Figs. 8a and 9). Since October, a group of spermatozoa in a spermatid-filled tubule has been observed in some individuals. As spring approached, larger numbers of individuals formed small clusters of spermatozoa in the tubules between spermatids (class 4, late maturation class, Fig. 8b). In October, spermatozoa were observed in 20% of individuals, and in late March, in 80% of individuals. During the spawning season in April, May, and June, some males had tubules filled with spermatids, and the efferent duct also contained spermatids. The number of spermatids decreased as the reproductive season progressed (class 4, late maturation class, Figs. 8c and 9). In other individuals, the lumen of the tubule showed spermatozoa or a combination of spermatozoa and spermatids, with the efferent duct containing the same cells. In June, the tubules appeared more empty, filled with fewer spermatids and/or spermatozoa (60% of individuals). In 15% of individuals, the gonads were undergoing regression (class 5; regression class), and in 25% of individuals, cell proliferation in the tubules has occurred (class 2, early maturation). In the latter gonads spermatocyte meiosis were observed at the edges of the tubules, along with secondary spermatocytes in the centers of the tubules released from the cysts (Fig. 9). In July, 10% of males had gonads in regression class (class 5). In 40% of individuals, the tubules were filled with secondary spermatocytes that exfoliated from cysts, which completed spermatogenesis in the tubule lumen. Peripherally, younger spermatogenic cells proliferated. Cysts usually contained small numbers of cells (class 2, early maturation). In 20% of individuals, the tubules were filled with larger numbers of older spermatogenic cells, while the periphery contained smaller numbers of cysts with proliferating cells, including primary spermatocytes (class 3, mid maturation, Fig. 8d). In 30% of males, the tubules were filled with secondary spermatocytes without cysts containing proliferating cells (class 4, late maturation) (Fig. 9). In August, one individual had gonads in regression class (class 5; 15%), while the rest of the individuals had gonads in mid maturation or late maturation class, with tubules filled with older spermatogenic cells (class 3 and 4; 85% of males) (Fig. 9). In September, all individuals were in the late maturation class with tubules filled with older spermatogenic cells. Single, quiescent spermatogonia A line the wall of the seminiferous tubule (Fig. 9). Since October, small groups of spermatozoa have been observed in spermatid-filled tubules, and the process of spermatozoa formation has slowly progressed toward spawning.

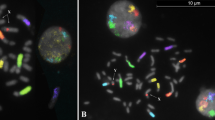

Histology of the testis of the male brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) inhabiting the oxbow lake of the Vistula River, Poland. A: testis in late maturation class; the entire lumen of the tubule was filled with early spermatids not enclosed in cysts (asterisk). A few reserved spermatogonia A were located on the high tubule wall (arrow), September. B: testis in the late maturation class; lumen tubules filled with spermatids, and a few cells have completed spermiogenesis, forming spermatozoa (asterisk), November. C: testis in the late maturation class at spawning; tubules filled with spermatids (white asterisk), and some tubules were empty (black asterisk). Spermatozoa may not be present in the cross-section of tubules during the spawning period May; D: the mid-maturation stage of the testis during the post-spawning period, the periphery of the tubules contains cysts with proliferating spermatogonia B and primary spermatocytes (arrow). The tubule lumen is filled with older spermatogenic cells exfoliating from cysts (asterisk). Usually, the cyst has a small number of cells. July. Scale bar: 50 μm. A, B, D: Heidenhain’s iron hematoxylin staining. C: Alcian blue with PAS staining.

The caudal region makes up about one-fifth of the length of the reproductive tract. The tubules in this region are lined with epithelial cells that change from cuboidal to cylindrical in shape during the sexual cycle. During the pre-spawning and spawning periods, a lumen appears in the tubules. Alcian blue staining with PAS showed no glycoprotein or mucin secretion in the lumens of the tubules (Fig. 10).

Histology of the caudal region of the reproductive system of the brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) male during the spawning period. The tubules are lined with cylindrical columnar epithelium. The lumen is open, but no spermatozoa or secretion were detected by alcian blue with PAS staining, May. Scale bar 50 μm.

Discussion

The brown bullhead is recognized as a threat species to European ichthyofauna. In such waters, this fish can quickly become dominant due to its high tolerance for low oxygen conditions and resistance to pollution and anthropogenic changes in fish habitats (e.g., river regulation), as well as interactions with native fish species28,29. In its new habitat, it reaches a smaller size compared to its native range30. The length of the fish in its native habitat ranges from 25.3 to 38.6 cm8. The maximum weight of a brown bullhead in its natural habitat is 2,700 g31while the maximum weight recorded in our study (central Poland) was 481.3 g (average 74.4 g). Populations of brown bullhead from Jagocinek Lake in northeastern Poland were even smaller, weighing between 4.2 and 241.3 g (mean of 57.0 ± 54.9 g) and measuring (TL) from 7.7 to 24.8 cm (mean of 14.6 ± 5.5 cm)14. Likewise, stable populations from four lakes in eastern Poland measured 6.4–26.7 cm (TL) and weighed between 3.2 and 283.3 g12,29,32. The individuals we analyzed were larger (TL ranged from 8.6 to 30.5 cm, and weight from 6.7 to 481.3 g), indicating that we can consider the population from the oxbow lake of the Vistula River to be stabilized. Additionally, smaller individuals were collected in Lake Czarne, measuring 7.2–15.4 cm (TL) and weighing between 3.9 and 36.8 g12as well as from Ukraine (SL 6.16–7.89 cm, weight 6.86–11.30 g) where only 0 + and 1 + individuals were present3. The individuals we analyzed were aged 1+−9+, which corresponds to the age of the brown bullhead in its natural environment33. The coefficient of condition in our study was higher (mean 1.83, range 0.84–2.9) for brown bullheads from the lakes of eastern Poland, compared to 0.2–1.834.

The GSI of the analyzed brown bullhead females fluctuated during their sexual cycle. The GSI reached its peak growth during the spawning period in our fish in June, averaging 1.88. In the case of the Canadians, the peak occurred in late May with a significantly higher GSI of about 822. Only a few of our females had a GSI above 3.0 during the spawning period. The low GSI in our brown bullhead may result from spawning over a longer timeframe, laying eggs multiple times compared to the shorter, typically single spawning of females in the native region16. In some areas, it has been reported that eggs can be laid more than once a year8. The multilaying of eggs by females with a low GSI, as observed in our study, was determined by microscopic images of the spawning gonads, which showed a group of mature oocytes remaining in the gonad after some eggs had been laid. In the case of brown bullheads, the histological image of the gonads, rather than the GSI, seems crucial for assessing the stage of gonad development, especially during the spawning period. The extended spawning period from mid-April to mid-June and the practice of partial spawning may represent an adaptation by this invasive species to master new habitats by laying smaller batches of eggs over a longer duration, while in their natural range, the rapid increase in GSI indicates a concentrated investment in gonads over a shorter timeframe and, consequently, a shorter spawning15. The GSI in male brown bullheads studied, as in most fish of the order Siluriformes, does not reach high values even during the spawning season, peaking at 0.49 at the beginning of spawning35,36,37,38,39. This value is similar to the peak GSI recorded in the United States of America of 0.46 but higher than that in Canada (0.26)15,17,20. The GSI value in males is considerably lower than in most other teleostean species, where the mean GSI in males exceeds 1, along with many more. The same is true for female brown bullheads studied, which showed a GSI value of 1.1–1.9. In other taxa, such as walleye (Sander vitreus), the GSI for males was recorded at 3.2, while females had a GSI of 7.640. In stone moroko (Pseudorasbora parva), it was 2-2.4 for males and 8.6 for females, respectively41,42. In other cyprinid fish, the GSI in males was even higher, averaging between 6 and 7, with females ranging from 10 to 1543,44. The low investment in gonads by both sexes of brown bullheads contributes to lower energy expenditure on reproduction and its allocation for guarding the nest, thus enhancing the reproductive success of the species.

In southern Canada, within the natural range of occurrence of brown bullhead, the spawning period lasts from June to mid-July, once water temperatures reach 20°C15. Meanwhile, in the northwestern part of the United States, spawning occurs from late May to early June at water temperatures between 14 and 29 °C or in July and August16,17. Among the Polish settler population, spawning happens earlier in the calendar year, specifically from mid-April to mid-June at a similar temperature as in the native region.

In the native region of the species, fish mature at 2+, 3 +8,9,15–18. In the population we analyzed, the smallest female to spawn was at age 1+. Even males can mature at age 1+. In white catfish from the United States, this has also been reported in females and males in a fast-growing population35. After spawning in our brown bullheads, we observe a substantial drop in female GSI in July (0.17) and faster oocyte growth in the fall compared to individuals in their natural habitat15 which may indicate favorable conditions for this species in its new environment range.

No data were found on brown bullhead fecundity in Europe. Regarding the fecundity of black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), the mean absolute fecundity was 3,319±1,521 eggs (1,111 − 12,727), and mean relative fecundity was 78.8±21.8 eggs g−1 (34.8–146.0)45. In our Vistula brown bullhead the fecundity was 3,227.08±2,794 (334 − 11,470) and 45.8±21.3 (11.7-113-3), respectively. In its natural range of occurrence, fecundity in the species was similar (1,000–13,000)8,9. As in the brown bullheads we analyzed, the number of oocytes positively correlated with black bullhead body length45. The histological image of the gonads of the studied brown bullheads shows a higher degree of oocyte vitellogenesis in the autumn period compared to other species such as ruffe46 perch47 or cyprinids43,48 indicating rapid oocyte maturation in the species studied. In the studied species, significant degeneration was found in November. The presence of numerous degenerating oocytes in the gonads of November females is unusual; in other species, mainly degenerating oocytes were observed during the spawning period until August or September. The numerous oocyte resorptions observed in spring, summer, and autumn may be caused by high temperatures and shortened photoperiod49. Such gonads were observed in fish living in heated cooling waters from the Ignalina Power Plant48,50 or the Dolna Odra Power Plant in Poland47. The presence of numerous degenerating oocytes in gonads sampled in November may therefore result from a shortened photoperiod and possibly from reduced food availability in the fall.

The male reproductive system of Siluriformes is morphologically diverse. This taxon includes fish with different types of fertilization, ranging from internal to external51. Many silurid families have lobed gonads with finger-like outgrowths, while others possess compact testes without lobes38,52,53,54,55,56. The reproductive tract consists of cranial and caudal regions. In some species, the medial (transition) region is delimited with spermatogenic/secretory functions53. In some catfish families, the testes contain spermatogonia distributed along the cranial and caudal regions. In other families, the caudal region of the reproductive system includes seminal vesicles or secretory cells without spermatogenic activity. In yet other species, this region has secretory and/or storage functions, or the secretory function has not been established, and its role requires further study52,53,57. In some Siluriformes, the reproductive tract also has blind pouches, which seem to be implicated in pheromone synthesis58,59. In the brown bullhead, as in other Ictaluridae and representatives of the Clariidae, Pimelodidae, Doradidae, and Auchenipteridae, paired fringed cranial and caudal regions have been identified35,38,52,53,57,60. In the fish we studied, the proportion of cranial to caudal regions was 4/5 to 1/5 and was similar to the rates of 3/4–4/5 to 1/4 − 1/5 reported by other authors15. The proportion among other representatives of Ictaluridae and Pimelodidae varies from 60 to 40% or 3/4 to 1/4 or 2/3 to 1/335,36,60–62. Significant differences in fringe lengths between the cranial and caudal regions were found in many species61. The shape and length of the reproductive tract’s lobes were shorter and thicker in the studied brown bullhead compared to most other representatives of the family35,38. A separate region in the reproductive system, called the seminal vesicle (glandular part), has been found in only a few groups of fish. In addition to catfish, it has been noted in blennies and gobies, but not in all representatives of these groups38,63,64. The shape, size, location, and function of the gland vary among species38,58,65,66,67,68. In blennies, the testicular glands primarily produce glycogen, which is involved in the nutrition and differentiation of germ cells, while unsulfated mucins are components of the seminal fluid69. The caudal region of the reproductive system in some fish of the order Siluriformes exhibits secretory activity and can form seminal vesicles38. Secretions containing neutral glycoproteins, acidic glycoconjugates, acidic carboxylates, sialomucins, and acidic and sulfated glycoconjugates53,60. In Clarias gariepinus, the seminal vesicles have been shown to produce steroid glucuronides, which can serve as a source of sexual attractants for females64,70. In the brown bullhead, the studied caudal region was devoid of reproductive cells, similar to the observation made by Burke and Leatherland15. The search by these authors for steroidogenic cells in this region rules out the steroidogenic function of this part. In our study, we did not find secretions stained with alcian blue-PAS in the lumen of the caudal tubules. The function of this part of the reproductive tract in the brown bullhead requires further study.

The testes of the brown bullhead consist of an anastomosing tubule of the unrestricted type, with spermatogonia A distributed along the tubules71,72. In fish, spermiation can occur at various stages of spermatogenesis, including spermatocytes, spermatids, or spermatozoa62,73,74. When cysts contain younger cells than spermatozoa, spermatogenesis is referred to as semi-cytic. In silurids, spermatogenesis can be classified as cystic or semi-cystic. Cystic spermatogenesis occurs in many of Siluriformes55,60,75,76. Semi-cystic spermatogenesis was observed in the families Cetopsidae, Asprenidae, Astrobleptidae, and Nematogenyidae73,77. This type of spermatogenesis has also been recorded in teleosts besides Siluriformes, such as Scorpaeniformes78,79,80 Lophiiformes81 and Blenniiformes65. In the brown bullhead studied, semi-cystic spermatogenesis was detected with cyst rupture at the stage of secondary spermatocytes entering the tubular lumen. In this species, Burke and Leatherland15 also noted the departure of cysts by secondary spermatocytes. The release of secondary spermatocytes has also been described in Notopterus notopterus82 while the passage of spermatids in Malapterurus electricus83 Hemigrammus marginatus84 Cetopsis coecutiens, Astroblepus sabalo, and Bunocephalus amazonicus73,77. In the histological picture of the gonads of the males we studied, similar to Burke and Leatherland15 we observed the arrangement of primary spermatocytes in cysts, with a small number of cells. Secondary spermatocytes left the cysts and accumulated in the lumen of the tubules. According to Burke and Leatherland15 the spermatid stage was a short-lived phase, as they were observed only during the three-week period before spawning. During the prespawning period, secondary spermatocytes transform into spermatids and spermatozoa. In our observations, the completion of the second meiotic division appears to have proceeded more rapidly, and the overwintering gonads were filled with spermatids or spermatids with forming spermatozoa that became more numerous as the spring spawning period approached. During spawning, few spermatozoa with spermatid dominance were typically observed in the seminal tubules. These characteristics of the sexual cycle of the brown bullhead under study were comparable to descriptions of spermatogenesis by Rosenblum et al.17 and in white catfish by Sneed and Clemens35. In fish with small testes and a large testicular gland, spermatids can be ejaculated into the seminal duct, where the final processes of differentiation into spermatozoa occur69,85. Fish from different taxa overwinter with gonads at varying maturity levels. The brown bullhead studied overwintered with tubules filled with spermatids. Representatives of fish from the order Perciformes (perch, walleye) and Gobiiformes (Chinese sleeper) overwinter with gonads filled with spermatozoa40,86,87. In other fish, the testes in the resting state consist mainly of spermatogonia42,43,44,88,89,90 or contain cysts with older spermatogenesis cells that form the first spermatozoa91. In these latter species, spawning begins earliest among other cyprinids, i.e. from early April.

Monitoring the spawning activity of brown bullheads provides significant information about the condition of this species in its habitat, as well as estimates on the likelihood of establishment in new areas and the rate of invasion92,93. Based on the results, it can be assumed that high fecundity, early maturation, and the possibility of partial spawning will contribute to the continued expansion of this species in Europe and an increase in density in water bodies where it already exists. Additionally, the estimated reproductive parameters can enhance the accuracy of models predicting population dynamics of brown bullhead changes in Central Europe, assisting resource managers in planning measures to control this invasive species. A favorable strategy for managing and eliminating this species from the environment, considering the brown bullhead’s high reproductive capacity and long breeding period, should involve catching the fish before it reaches sexual maturity. Techniques for managing invasive species, including eradication and population control, vary widely and encompass chemical measures, fishing practices, physical removal, and biological control. Among these methods, chemical treatments (such as antimycin and rotenone) and electric and net fishing have proven to be relatively effective94,95. However, these methods also impact native fish and necessitate intensive efforts and repeated treatments over many years, leading to increasing concerns about their questionable effects96. From an ecological viewpoint, a more effective approach to reducing invasive fish populations may involve improving natural environmental conditions and processes through restoration97 as fish have been recognized as key indicators reflecting the biotic response to river restoration98. In the long term, this leads to the restoration of habitat diversity and suitable water physicochemical conditions, thereby supporting the development of unique assemblages of native fishes99. The natural restoration of native fishes can either promote or hinder the presence of invasive fish species100.

Our studies should continue in the coming years, primarily focusing on juveniles, to examine recruitment trends before these fish enter the reproductive phase and to determine how management actions related to the removal of this species will influence recruitment and changes in the structure of the basin’s ichthyofauna.

Conclusion

In the study, brown bullheads in the new habitat were characterized by multiple egg-laying, earlier maturation of individuals, and spawning during the earlier period of the calendar year, i.e., mid-April to mid-June, compared to their native habitat, indicating high plasticity in adapting to new environments. Biological characteristics of the brown bullhead, such as low living requirements, a low GSI indicating less investment in gonad development compared to other fish, parental nest protection, and probably many other factors to be defined in the future, contribute to the species’ competitiveness and successful colonization of new areas where they become invasive species. The results of this study will help managers identify the reproductive potential of brown bullheads in new areas of occurrence and more accurately estimate population structure and invasive potential.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Welcomme, R. L. International introductions of inland aquatic species. FAO Fisheries Tech. Papers. 294, 1–318 (1988).

Elvira, B. First records of the North American catfish Ictalurus melas (Rafinesque, 1820) (Pisces, Ictaluridae) in Spanish waters. Cybium 8, 96–98 (1984).

Kutsokon, I., Kvach, Y., Dykyy, I. & Dzyziuk, N. The first finding of the brown bullhead Ameiurus nebulosus (Le sueur, 1819) in the Dniester river drainage, Ukraine. Bioinvasions Records. 7, 319–324. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.3.14 (2018).

Kutsokon, Y. et al. Jr. The expansion of invasive species to the east: new sites of the bullheads (genus Ameiurus Rafinesque 1820) in Ukraine with morphological and genetic identification. J. Fish Biol. 105, 3, 708–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.15778 (2024).

Rutkayová, J., Biskup, R., Harant, R., Šlechta, V. & Koščo, J. Ameiurus melas (black bullhead): morphological characteristics of new introduced species and its comparison with Ameiurus nebulosus (brown bullhead). Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 23, 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-012-9274-6 (2013).

Barnes, G. E. & Hicks, B. J. Brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurusnebulosus) in Lake Taupo. pp. 27–35 In: Munro, R. (ed.). ManagingInvasiveFreshwaterFishinNewZealand. Proceedings of a workshop hosted by Department of Conservation pp. 27–35, Wellington, New Zealand 10–12 May 2001, Hamilton. (2003).

Grabowska, J., Kotusz, J. & Witkowski, A. Alien invasive fish species in Polish waters: an overview. Folia Zool. 59, 73–85. https://doi.org/10.25225/fozo.v59.i1.a1.2010 (2010).

Scott, W. B. & Crossman, E. J. Freshwater fishes of Canada. Bulletin - Fisheries Res. Board. Canada Ott. 184, 1–966 (1973).

Jones, P. W., Martin, F. D. & Hardy, J. D. Jr Development of fishes of the Mid-Atlantic Bight. An atlas of eggs, larval and juvenile stages. Vol. 1. Acipenseridae through Ictaluridae. U.S. Fish Wildl. Ser. Biol. Serv. Program FWS/OBS-78/12. ISBN 77-86193 319–322 p. 336 p. (1978).

Kornijów, R., Rechulicz, J. & Halkiewicz, A. Brown bullhead (Ictalurus nebulosus Le Sueur) in ichthyofauna of several Polesie lakes differing in trophic status. Acta Sci. Pol. (Piscaria). 2, 131–140 (2003).

West, G. Methods of assessing ovarian development in fishes: a review. Aust J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 41, 199–222 (1990).

Kapusta, A., Morzuch, J., Partyka, K. & Bogacka-Kapusta, E. First record of brown bullhead, Ameiurus nebulosus (Lesueur), in the Łyna river drainage basin (northeast Poland). Archiv Pol. Fish. 18, 261–265. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10086-010-0030-z (2010).

Rechulicz, J. & Płaska, W. The invasive Ameiurus nebulosus (Lesueur, 1819) as a permanent part of the fish fauna in selected reservoirs in central europe: long-term study of three shallow lakes. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 42, 464–474. https://doi.org/10.3906/zoo-1710-16 (2018).

Ulikowski, D., Traczuk, P. & Kalinowska, K. Abundance and size structure of invasive brown bullhead, Ameiurus nebulosus (Lesueur, 1819), in a mesotrophic lake (north-eastern Poland). Bioinvasions Rec. 11, 1, 267–277. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2022.11.1.27 (2022).

Burke, M. G. & Leatherland, J. F. Seasonal changes in testicular histology of brown bullheads, Ictalurus nebulosus lesueur. Can. J. Zool. 62, 1185–1194. https://doi.org/10.1139/z84-171 (1984).

Blumer, L. S. Reproductive natural history of the brown bullhead, Ictalurus nebulosus. Environ. Biol. Fish. 12, 231–236 (1985).

Rosenblum, P. M., Pudney, J. & Callard, I. P. Gonadal morphology, enzyme histochemistry and plasma steroid levels during the annual reproductive cycle of male and female brown bullhead catfish, Ictalurus nebulosus lesueur. J. Fish. Biol. 31, 325–341 (1987).

Jenkins, R. E. & Burkhead, N. M. Freshwater Fishes of Virginia, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD. pp 1,080 (1993).

Oliva, O. Sumeček Americký (Ameiurus nebulosus Le sueur 1819). Akvaristicke Listy. 22, 74–75 (1950).

Burke, M. G., Leatherland, J. F. & Sumpter, J. P. Seasonal changes in serum testosterone, 11 -ketotestosterone, and estradiol l7β levels in the brown bullhead, Ictalurus nebulosus lesueur. Can. J. Zool. 62 (1), 1195 (1984).

Campana, S. E. Accuracy, precision, and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J. Fish. Biol. 59, 197–242 (2001).

Buckmeier, D. L., Irwin, E. R., Betsill, R. K. & Prentice, J. A. Validity of otoliths and pectoral spines for estimating ages of channel catfish. N Am. J. Fish. Manag. 22, 934–942 (2002).

Barada, T. J. & Blank, A. J. & M. A. Pegg. Bias, precision, and processing time of otoliths and pectoral spines used for age estimation of channel catfish. Pages 723–732 in P. H. Michaletz and V. H. Travnichek, (eds.) Conservation, ecology, and management of catfish: the second international symposium. American Fisheries Society, Symposium 77, Bethesda, Maryland (2011).

Nash, R., Valencia, A. H. & Geffen, A. J. Origin of fulton’s condition Factor—Setting the record straight. Fisheries 31, 236–238 (2006).

Grier, H. J. The germinal epithelium: Its dual role in establishing male reproductive classes and understanding the basis for indeterminate egg production in female fishes. In: Creswell RL, editor. Proceedings of the Fifty-Third Annual Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute, November 2000. Fort Pierce, FL: Mississippi/Alabama Sea Grant Consortium. pp 537–552 (2002).

Kjesbu, O. & Holm, J. Oocyte recruitment in first-time spawning Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) in relation to feeding regime. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 51, 1893–1898. https://doi.org/10.1139/f94-189 (1994).

Sokal, R. R., Rohlf, F. J. & Biometry The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research. 3rd Edition, W.H. Freeman and Co., New York (1995).

Witkowski, A. & Grabowska, J. The Non-Indigenous freshwater fishes of poland: threats to the native ichthyofauna and consequences for the fishery: A review. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 42, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.3750/AIP2011.42.2.01 (2012).

Rechulicz, J. & Płaska, W. The diet of non-indigenous Ameiurus nebulosus of varying size and its potential impact on native fish in shallow lakes. Global Ecol. Conserv. 31, e01881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01881 (2021).

Copp, G. H. et al. A review of growth and life-history traits of native and non-native European populations of black bullhead Ameiurus melas. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 26, 441–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-016-9436-z (2016).

IGFA. Database of IGFA Angling Records until 2001 (IGFA, 2001).

Rechulicz, J. & Płaska, W. Inter-population variability of diet of the alien species brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) from lakes with different trophic status. Turkish J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 19, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.4194/1303-2712-v19_1_07 (2019).

Kottelat, M. & Freyhof, J. Handbook of European freshwater fishes. Publications Kottelat, Cornol and Freyhof, Berlin. 646 pp. ISBN 978-2-8399-0298-4 (2007).

Kalinowska, K., Ulikowski, D., Traczuk, P. & Rechulicz, J. Changes in native fish communities in response to the presence of alien brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) in four lakes (Poland). Biol. Invasions. 25, 2891–2900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03079-3 (2023).

Sneed, K. E. & Clemens, H. P. The morphology of the testes and accessory reproductive glands of the catfishes (Ictaluridae). Copeia 4, 606–611 (1963).

Guest, W. C., Avault, J. W. Jr. & Roussel, J. D. A spermatology study of channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 105, 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1976)105<463:ASSOCC>2.0.CO;2 (1976).

Jaspers, E. J., Avault, J. W. Jr. & Roussel, J. D. Characteristics of channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, outside the spawning season. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 107, 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1978)107<309:TASCOC>2.0.CO;2 (1978).

Loir, M., Planquette, C. C. & Le Bail, P. Comparative study of the male reproductive tract in seven families of South-American catfishes. Aquat. Living Resour. 2, 45–56 (1989).

Bosworth, B., Quiniou, S. & Chatakondi, N. Effects of season, strain, and body weight on testes developmentand quality in three strains of blue catfish, Ictalurus furcatus. J. World Aquac Soc. 49, 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12419 (2018).

Malison, J. A., Procarione, L. S., Barry, T. P., Kapuscinski, A. R. & Kayes, T. B. Endocrine and gonadal changes during the annual reproductive cycle of the freshwater teleost, Stizostedion vitreum. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 13, 473–484 (1994).

Asahina, K., Hirose, H. & Hibiya, T. Annual reproductive cycle of the Topmouth gudgeon Pseudorasbora parva in the Tama river. Nippon Suisan Gakk. 56, 243–247 (1990).

Kirczuk, L., Dziewulska, K., Czerniejewski, P. & Brysiewicz, A. Rząd I. Reproductive potential of stone Moroko (Pseudorasbora parva, Temminck et schlegel, 1846) (Teleostei: cypriniformes: Gobionidae) inhabiting central Europe. Animals 11 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092627 (2021).

Domagała, J., Dziewulska, K., Kirczuk, L. & Pilecka-Rapacz, M. Sexual cycle of white bream, Blicca bjoerkna (Actinopterygii, cypriniformes, Cyprinidae), from three sites of the lower Oder River (NW Poland) differing in temperature regimes. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 45, 285–298. https://doi.org/10.3750/AIP2015.45.3.07 (2015).

Domagała, J., Kirczuk, L., Dziewulska, K. & Pilecka-Rapacz, M. The annual reproductive cycle of rudd, Scardinius erythrophthalmus (Cyprinidae) from the lower Oder river and lake dąbie, (NW Poland). Fol Biol. (Kraków). 68 (1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.3409/fb_68-1.04 (2020).

Varga, J. et al. Fecundity, growth and body condition of invasive black bullhead (Ameiurus melas) in eutrophic oxbow lakes of River-Körös (Hungary). Bioinvasions Rec. 13, 2, 515–527. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2024.13.2.16 (2024).

Domagała, J., Kirczuk, L. & Pilecka-Rapacz, M. Annual development cycle of gonads of Eurasian Ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernuus L.) females from lower Odra river sections differing in the influence of cooling water. J. Freshw. Ecol. 28, 3, 423–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2013.777855 (2013).

Kirczuk, L., Domagała, J. & Pilecka-Rapacz, M. Annual Developmental Cycle of Gonads of European Perch Females (Perca fluviatilis L.) from Natural Sites and a Canal Carrying Post-cooling Water from the Dolna Odra Power Plant (NW Poland). Folia Biol. (Krakow). 63,2, 85–93 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3409/fb63_2.85. PMID: 26255460.

Domagała, J., Kirczuk, L., Dziewulska, K. & Pilecka-Rapacz, M. 795 annual development of gonads of pumpkinseed, Lepomis gibbosus (Actinopterygii: perciformes: Centrarchidae) from a heated-water discharge Canal of a power plant in the lower stretch of the Oder river, Poland. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 44, 2, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.3750/AIP2014.44.2.07 (2014).

Sandström, O., Neuman, E. & Thoresson, G. Effects of temperature on life history variables in perch. J. Fish. Biol. 47, 652–670 (1995).

Lukšjenė, D., Sandström, O., Lounasheimo, L. & Andersson, J. The effects of thermal effluent exposure on the gametogenesis of female fish. J. Fish. Biol. 56, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1994.tb00928.x (2000).

Melo, R. M. et al. Comparative morphology of the gonadal structure related to reproductive strategies in six species of Neotropical catfishes (Teleostei: Siluriformes). J. Morp. 272, 525–535 (2011).

Meisner, A. D., Burns, J. R., Weitzman, S. H. & Malabarba, L. R. Morphology and histology of the male reproductive system in two species of internally fertilizer South American catfishes. Trachelyopterus lucenai and T. galeatus (Teleostei: Auchenipteridae). J. Morphol. 246, 131–141 (2000).

Santos, J. E., Bazzoli, N., Rizzo, E. & Santos, G. B. Morphofunctional organization of the male reproductive system of the catfish Iheringichthys labrosus (Lütken, 1874) (Siluriformes:Pimelodidae). Tissue Cell. 33 (5), 533–540 (2001).

54, Guimarães-Cruz, R. J. & Santos, J. E. Testicular structure of three species of Neotropical freshwater pimelodids (Pisces, Pimelodidae). Rev. Bras. Zool. 21, 267–271 (2004).

Lopes, D. C. J. R., Bazzoli, N., Brito, M. F. G. & Maria, T. A. Male reproductive system in the South American catfish Conorhynchus conirostris. J. Fish. Biol. 64, 1419–1424 (2004).

Mazzoldi, C., Lorenzi, V. & Rasotto, M. B. Variation of male reproductive system in relation to fertilization modalities in the catfish families Auchenipteridae and Callichthyidae (Teleostei: Siluriformes). J. Fish. Biol. 70, 243–256 (2007).

Legendre, M., Linhart, O. & Billard, R. Spawning and management of gametes, fertilized eggs and embryos in silurioidei. Aquat. Living Resour. 9, 59–80 (1996).

Patzner, R. A. Morphology of the male reproductive systems of two indopacific blenniid fishes Salarias fasciatus and Escenius bicolor (Blenniidae. Teleostei) Z Zool. Syst. Evolut Forsch. 27, 135–141 (1989).

Lahnsteiner, F., Nussbaumer, B. & Patzner, R. A. Unusual testicular accessory organs, the testicular blind pouches of blennies (Teleostei, Blenniidae). Fine structure, (enzyme-) histochemistry and possible functions. 42, 227–241 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1993.tb00324.x

Santos, J. E., Veloso-Junior, V. C. & Andrade Oliveira, D. A. Hojo. R. E. Morphological characteristics of the testis of the catfish Pimelodella vittate (Lutken, 1874). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 26, 942–945 (2010).

Cruz, R. J. G. & Santos, J. E. Testicular structure of three species of Neotropical freshwater pimelodids (Pisces, Pimelodidae). Rev. Bras. Zool. 21, 267–271 (2004).

Santos, M. L. et al. Anatomical and histological organization of the testes of the inseminating catfish Trachelyopterus striatulus (Steindachner, 1877) (Siluriformes: Auchenipteridae. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 43, 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahe.12082 (2014).

de Jonge, J., de Ruiter, A. J. H. & van den Hurk, R. Testis-testicular gland complex of two Tripterygion species (Blennioidei, Teleostei): differences between territorial and non-territorial males. J. Fish. Biol. 35, 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1989.tb03001.x (1989).

Van den Hurk, R., Resink, J. W. & Peute, J. The seminal vesicle of the African catfish, Clarias gariepinus A histological, histochemical, enzyme-histochemical, ultrastructural and physiological study. Cell. Tissue Res. 247, 573–582 (1987).

Lahnsteiner, F., Richtarski, U. & Patzner, R. A. Functions of the testicular gland in two blenniid fishes, Salaria (= Blennius) pavo and Lipophrys (= Blennius) dalmatinus (Blenniidae, Teleostei) as revealed by electron microscopy and enzyme histochemistry. J. Fish. Biol. 37, 85–97 (1990).

Fishelson, L. Comparative cytology and morphology of seminal vesicles in male gobiid fishes. Japanese J. Ichthyol. 38, 17–30 (1991).

Miller, P. J. The sperm duct gland: a visceral synapomorphy for gobioid fishes. Copeia 1, 253–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/1446565 (1992).

Patzner, R. A. & Lahnsteiner, F. The Biology of Blennies. In R. A. Patzner, E. J. Gonçalves, P. A. Hastings, Kappor, B. G. Reproductive Organs in Blennies. Imprint CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, UK (2009).

Lahnsteiner, F. & Patzner, R. A. The speramatic ducts of blenniid fish (Teleostei, Blenniidae): fine structure, histochemistry and function. Zoomorphol 110, 63–73 (1990).

Resink, J. W., Van Den Hurk, R. & Van Zoelen, G. Huisman E.A. The seminal vesicle as source of sex attracting substances in the African catfish. Clarias gariepinus Aquaculture. 63, 115–127 (1987).

Grier, H. J. Cellular organization of the testis and spermatogenesis in fishes. Am. Zool. 21, 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/21.2.345 (1981).

Parenti, L. R. & Grier, H. J. Evolution and phylogeny of gonad morphology in bony fishes. Integr. Comp. Biol. 44, 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.5.333 (2004).

Spadella, M. A., Oliveira, C. & Quagio-Grassiotto, I. Occurrence of biflagellate spermatozoa in the Siluriformes families cetopsidae, aspredinidae, and Nematogenyidae (Teleostei: Ostariophysi). Zoomorphology 125, 135–145 (2006a).

Spadella, M. A., Oliveira, C. & Quagio-Grassiotto, I. Spermiogenesis and introsperm ultrastructure of Scoloplax distolothrix (Ostariophysi: siluriformes: Scoloplacidae). Acta Zoologica (Stockholm). 87, 341–348 (2006b).

Santos, J. E. et al. Reproductive biology of the Neotropical catfish Iheringichthys labrosus (Siluriformes: Pimelodidae), with anatomical and morphometric analysis of gonadal tissues. Anim. Repr Sci. 209, 106173 (2019).

Barros, M. D. M., Guimarães-Cruz, R. J., Veloso-Júnior, V. C. & dos Santos, J. E. Reproductive apparatus and gametogenesis of Lophiosilurus alexandri Steindachner (Pisces, teleostei, Siluriformes). Rev. Bras. Zool. 24, 213–221 (2007).

Spadella, M. A., Oliveira, C., Ortega, H., Quagio-Grassiotto, I. & Burns, J. R. Male and female reproductive morphology in the inseminating genus Astroblepus (Ostariophysi: siluriformes: Astroblepidae). Zool. Anz. 251, 38–48 (2012).

Mattei, X., Siau, Y., Thiaw, O. T. & Thiam, D. Peculiarities in the organization of testis of Ophidion sp. (Pisces Teleostei). Evidence for two types of spermatogenesis in teleost fish. J. Fish. Biol. 43, 931–937 (1993).

Muňoz, M., Yasunori, K. & Casadevall, M. Histochemical analysis of sperm storage in Helicolenus dactylopterus (Teleostei: Scorpaenidae). J. Exp. Zool. 292, 156–164 (2002).

Hernández, M. R., Sábat, M., Muňoz, M. & Casadevall, M. Semicystic spermatogenesis and reproductive strategy in Ophidion barbatum (Pisces, Ophidiidae). Acta Zool. 86, 295–300 (2005).

Yoneda, M. et al. Reproductive cycle and sexual maturity of the anglerfish Lophiomus setigerus in the East China sea with a note on specialized spermatogenesis. J. Fish. Biol. 53, 164–178 (1998).

Shrivastava, S. S. Histomorphology and seasonal cycle of the spermary and duct in teleost Notopterus notopterus (Pallas). Acta Anat. 66, 133–160 (1967).

Shahin, A. A. B. Semicystic spermatogenesis and biflagellate spermatozoon ultrastructure in the nile electric catfish Malapterurus electricus (Teleostei: siluriformes: Malapteruridae). Acta Zool. 87, 215–227 (2006).

Magalhães, A. L. B. et al. Ultrastructure of the semicystic spermatogenesis in the South American freshwater characid Hemigrammus marginatus (Teleostei: Characiformes). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 27, 1041–1046 (2011).

Rasotto, M. B. Male reproductive apparatus of some Blennioidei (Pisces: Teleostei). Copeia 4, 907–914 (1995).

Sulistyo, I. et al. Reproductive cycle and plasma levels of steroids in male Eurasian perch Perca fluviatilis. Aquat. Living Resour. 13, 99–106 (2000).

Kirczuk, L. et al. Annual reproductive cycle of Chinese sleeper peacotums glenii, dybowski, 1877 (Teleostei: gobiiformes: Odontobutidae) an invasive fish inhabiting central Europe. Eur. Zool. J. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2023.2301438 (2024).

Bhatti, M. N. & Al-Daham, N. K. Annual cyclical changes in testicular activity of a freshwater teleost. Burbus luteus (Heckel) from Shatt-Al-Arab, Crag. J. Fish Biol. 13, 321–326 (1978).

Shrestha, T. K. & Khanna, S. S. Seasonal changes in the testes of a hill stream teleost, Gaurragotryla (Gray). Acra Anat. 100, 210–220 (1978).

Dziewulska, K. & Domagała, J. Histology of salmonid testes during maturation. Reprod. Biol. 3, 47–61 (2003).

Domagała, J., Dziewulska, K., Kirczuk, L. & Pilecka-Rapacz, M. Sexual cycle of the blue Bream (Ballerus ballerus) from the lower Oder river and Dąbie lake (NW Poland). Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 18, 1147–1116. https://doi.org/10.4194/1303-2712-v16_4_08 (2016).

Brown-Peterson, N. J., Wyanski, D. M., Saborido-Rey, F., Macewicz, B. J. & Lowerre-Barbieri, S. K. A standardized terminology for describing reproductive development in fishes. Mar. Coast Fish. 3, 52–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/19425120.2011.555724 (2011).

Brewer, S. K., Rabeni, C. F. & Papoulias, D. M. Comparing histology and gonadosomatic index for determining spawning condition of small bodied riverine fishes. Ecol. Freshw. Fish. 17, 54–58 (2008).

Britton, J. R., Brazier, M., Davies, G. D. & Chare, S. I. Case studies on eradicating the Asiatic cyprinid Pseudorasbora parva from fishing lakes in England to prevent their riverine dispersal. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwat Ecosyst. 18, 867–876 (2008).

Ziou, A. et al. Use of electrofishing to limit the spread of a Non-Indigenous fish species in the impoundment of Aoos springs (Greece). Limnological Rev. 24, 374–384. https://doi.org/10.3390/limnolrev24030022 (2024).

Rytwinski, T. et al. The effectiveness of non-native fish removal techniques in freshwater ecosystems: a systematic review. Environ. Reviews. 27, 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2018-0049 (2019).

Poppe, M. et al. Assessing restoration effects on hydromorphology in European mid-sized rivers by key hydromorphological parameters. Hydrobiologia 769, 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-015-2468-x (2016).

Haase, P., Hering, D., Jähnig, S. C., Loren, A. W. & Sundermann, A. z The impact of hydromorphological restoration on river ecological status: a comparison of fish, benthic invertebrates, and macrophytes. Hydrobiologia 704, 475–488 (2012).

Ramler, D. & Keckeis, H. Effects of hydraulic engineering restoration measures on invasive gobies in a large river (Danube, Austria). Biol. Invasions. 22, 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-019-02101-x (2020).

Jude, D. J. & DeBoe, S. F. Possible impact of gobies and other introduced species on habitat restoration efforts. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 53, 136–141 (1996).

Acknowledgements

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank the technical staff of the University of Szczecin, especially Anna Kompowska and Iwona Goździk for making the histological slides.

Funding

Co-financed by the Minister of Science under the “Regional Excellence Initiative” Program for 2024–2027 (RID/SP/0045/2024/01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributionsConceptualization: K.D., L.K. and P.C., methodology: K.D. and L.K.; formal analysis: K.D., L.K., P.C., J.R., J.L. and A.B., investigation: K.D., L.K., P.C., J.R., J.L. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation: K.D., L.K.; writing—review and editing: K.D., L.K., P.C., J.R., J.L. and A.B.; visualization: K.D. and L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kirczuk, L., Dziewulska, K., Czerniejewski, P. et al. Annual gonadal cycle of the invasive catfish brown bullhead Ameiurus nebulosus from an oxbow lake of Vistula river, Poland. Sci Rep 15, 24507 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10597-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10597-8