Abstract

In Palestine, breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent cancer among women. This study explored the relationship between eligibility for BC screening and the time taken for seeking medical advice for possible BC symptoms. It also identified the barriers hindering early presentation among screening-eligible and ineligible Palestinian women. Palestinian females from governmental hospitals, primary healthcare centers, and diverse public venues across 11 governorates within Palestine were recruited using convenience sampling. A modified, translated-into-Arabic version of the BC Awareness Measure was utilized for data collection. The questionnaire comprised three sections: sociodemographic information, duration for seeking medical advice upon recognizing each of 13 possible BC symptoms, and barriers impeding early presentation. The final analysis included 2796 participants, with 2168 (77.5%) ineligible for BC screening and 628 (22.5%) eligible. The proportion of participants who would seek medical advice immediately varied depending on the nature of BC symptoms. Approximately half of participants in both the screening-eligible (n = 1097, 50.6%) and ineligible (n = 293, 46.7%) groups indicated that they would seek immediate medical advice for ‘lump or thickening in the breast.’ Similarly, about half of participants in both groups reported an inclination to seek immediate medical advice for ‘nipple discharge or bleeding’ (screening-eligible: n = 954, 44.0%; screening-ineligible: n = 280, 44.6%). Less than half of participants would seek immediate medical advice for other BC symptoms. Screening-eligible women were more likely to seek advice within a week for six out of 13 possible BC symptoms than screening-ineligible women. Among screening-eligible participants, 9.9% (n = 62) acknowledged a delay in seeking medical attention upon recognizing a potential BC symptom. Emotional barriers were most frequently reported, with ‘disliking the visit to healthcare facilities’ identified as the leading barrier among screening-eligible participants (n = 38, 61.3%). No association was found between BC screening eligibility and the total or type-specific number of reported barriers. Differences in immediate medical advice seeking for various BC symptoms were observed between screening-eligible and ineligible groups. Emotional barriers were the most prevalent in both groups. Tailored interventions to enhance BC awareness and address barriers to early presentation are essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) has emerged as the most frequently diagnosed cancer globally, presenting a significant challenge to public health1. Currently, BC constitutes 1 in 8 newly diagnosed cancer cases, amounting to 2.3 million new cases across both genders1. Projections indicate a substantial increase, with an expected 40% rise in newly diagnosed BC cases, reaching approximately 3 million annually by 2040. In addition, BC-related deaths are projected to surge by over 50%, escalating from 685,000 in 2020 to 1 million in 20402. Notably, BC is the most prevalent cancer among Palestinian women, accounting for 35.6% of documented cases of female cancers in Palestine. The age-standardized incidence and mortality rates are 53.5 and 22.6 per 100,000 female population, respectively, in Palestine3.

Early detection of BC significantly increases the likelihood of successful treatment compared to later-stage diagnoses4. In countries with low-resource settings, many BC patients face delays in diagnosis, leading to advanced-stage detection and reduced survival rates5,6. In Palestine specifically, advanced stages account for over 60% of BC cases, reducing the likelihood of positive outcomes7. Furthermore, despite the availability of a fully accessible and cost-free screening program8, the utilization of mammography in Palestine continues to be notably low9. This underscores the urgency of emphasizing timely detection of BC through screening measures and improved awareness of BC, as these factors play a crucial role in influencing prognosis and reducing the morbidity and mortality rates associated with BC10.

Nevertheless, various barriers, including emotional, service-related, and practical barriers, may hinder women from promptly seeking medical attention11. Assessing the current understanding of BC and barriers associated with timely presentation among Palestinian women eligible for BC screening is imperative, especially given the documented low participation rates in BC screening12. Therefore, this national study aimed to examine the association between BC screening eligibility and the anticipated time for seeking medical advice among Palestinian women. It also aimed to identify and compare barriers to early presentation between screening-eligible and ineligible women.

Methods

Study design and population

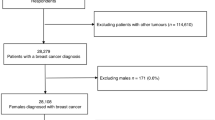

This nationwide cross-sectional study was carried out from July 2019 to March 2020, targeting adult Palestinian women living in Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. Exclusion criteria included women visiting oncology departments or clinics during the data collection period, women with history of any breast disease(s), those with healthcare background, non-Palestinian nationals, women with family history of cancer, women who underwent screening mammography, and those unable to complete the questionnaire.

Sampling methods

Eligible women were enrolled utilizing convenience sampling from specified data collection sites, including primary healthcare centers, governmental hospitals, and public venues distributed across 11 governorates in Palestine (seven in the West Bank and Jerusalem, and four in the Gaza Strip). Public venues included restaurants, markets, downtown areas, parks, malls, churches, mosques, and public transportation stations. The inclusion of participants from various locations and governorates across Palestine was intended to enhance the representativeness and diversity of the study cohort13,14,15.

Questionnaire and data collection

A modified version of the validated Breast Cancer Awareness Measure (BCAM) assessment tool was utilized for data collection16. The original BCAM in English underwent translation into Arabic by two bilingual experts, followed by back-translation into English by two different bilingual experts. Evaluation of the Arabic BCAM version involved five experts specializing in BC, public health, and survey design to ensure content validity and translation accuracy. A pilot study with 35 participants was conducted to assess the clarity of questions in the Arabic BCAM. Responses from the pilot study were excluded from the final analysis. The internal consistency of the Arabic BCAM was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha, which yielded a satisfactory value of 0.75.

The study questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section gathered sociodemographic information including age, marital status, highest level of education, employment status, monthly income, place of residency, presence of chronic diseases, knowing someone diagnosed with cancer, and the site of data collection. The second section evaluated the anticipated time women would take to seek medical consultation for each of 13 possible BC symptoms. Eleven symptoms were retained from the original BCAM16, with the addition of two other symptoms, namely ‘extreme generalized fatigue’ and ‘unexplained weight loss’ based on previous studies11,17,18. The third section explored perceived barriers to early presentation, categorized into emotional, service-related, and practical barriers.

The data collection process utilized Kobo Toolbox, a secure and user-friendly platform accessible via smartphones19. Trained female data collectors with a medical background underwent comprehensive training to conduct face-to-face interviews for questionnaire completion through the Kobo Toolbox platform. The inclusion of female data collectors aimed to mitigate potential discomfort among women when responding to sensitive questions.

Exposure and outcome

Our group recently demonstrated various proportions of participants who would immediately seek medical advice for possible BC symptoms and identified different barriers to early presentation within the general population20. However, there exists a gap in the literature regarding the specific examination of these aspects among women who are eligible for BC screening compared to those who are not. Subsequently, the primary exposure in this study was the eligibility to undergo BC screening, defined as aging 40 to 74 years while having an average-risk of developing BC (i.e., no family history of cancer or personal history of breast disease). The primary outcome measure was the proportion of participants who would seek immediate medical advice for each BC symptom, stratified by eligibility to undergo BC screening. The secondary outcome measure was the proportion of reported barriers that could potentially hinder a visit to the doctor when a BC symptom is recognized.

Statistical analysis

In Palestine, BC screening is recommended for women aged 40 and above21. Accordingly, age was categorized into two groups: 18–39 years and ≥ 40 years. Similarly, monthly income was divided into two categories: < 1450 NIS and ≥ 1450 NIS, based on the minimum wage in Palestine, approximately equivalent to $45022.

The median and interquartile range (IQR) were utilized to depict continuous variables exhibiting non-normal distributions. Conversely, categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Baseline characteristics between screening-eligible and ineligible participants were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and the Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables.

Symptoms of BC were classified into three categories: (i) breast symptoms, (ii) nipple symptoms, and (iii) other symptoms. Additionally, the expected timeframe to seek medical advice for potential BC symptoms was divided into four groups: immediate (≤ 24 h), ≤ 7 days, > 7 days, and never. The frequency and percentage distribution of anticipated timeframes were analyzed, and a comparison between screening-eligible and ineligible participants was conducted using the Pearson chi-square test.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed to assess the association between eligibility for BC screening and the expected time to seek medical advice for potential BC symptoms. The multivariable model was adjusted for covariates including age group, educational level, employment status, monthly income, marital status, place of residence, presence of a chronic disease, familiarity with someone diagnosed with cancer, and site of data collection. This model was determined a priori based on prior studies13,14,15,20.

In line with prior studies16,20,21, barriers to early presentation were categorized into emotional, service-related, and practical barriers. The frequencies and percentages of reported barriers were analyzed and compared between screening-eligible and ineligible participants using the Pearson chi-square test. The median number of barriers in each category served as the cutoff point to dichotomize the number of displayed barriers (overall, emotional, service, and practical). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was then conducted to explore the association between BC screening eligibility and the presence of at least the median number of barriers to early presentation, utilizing the previously mentioned multivariable model.

Missing data were hypothesized to be missed completely at random and were handled through a complete case analysis approach. The data analysis was conducted using Stata software version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Participant characteristics

The final analysis included 2796 participants, with 2168 (77.5%) ineligible for BC screening and 628 (22.5%) eligible (Table 1). Participants in the BC screening-eligible group were older, exhibited higher unemployment rates, reported lower monthly income and educational level, and suffered from more frequent chronic diseases.

Immediate seeking of medical advice for a possible BC symptom in BC screening-eligible vs ineligible groups

Approximately half of participants in both the screening-eligible (n = 1097, 50.6%) and ineligible (n = 293, 46.7%) groups indicated that they would seek immediate medical advice for ‘lump or thickening in the breast’ (Table 2). However, less than one third of participants in both groups would seek medical advice immediately for other breast symptoms.

Similarly, about half of participants in both groups reported an inclination to seek immediate medical advice for ‘nipple discharge or bleeding’ (screening-eligible: n = 954, 44.0%; screening-ineligible: n = 280, 44.6%). About one third of study participants or less reported immediate seeking of medical advice for other nipple symptoms.

Less than half of participants would seek immediate medical advice for other BC symptoms, with ‘lump or thickening under the armpit’ reported as the most concerning symptom in both groups (screening-eligible: n = 937, 43.2%; screening-ineligible: n = 278, 44.3%). The proportion of immediate seeking of medical advice was lower for other BC symptoms, with ‘extreme generalized fatigue’ receiving the least priority for immediate medical attention in both groups (screening-eligible: n = 241, 11.1%; screening-ineligible: n = 88, 14.0%).

Association between eligibility for BC screening and no seeking of medical advice

Screening-eligible women had a lower likelihood of not seeking medical advice for six out of 13 possible BC symptoms, namely ‘redness of the breast skin’ (OR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.53–0.88), ‘nipple rash’ (OR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.58–0.99), ‘changes in the shape of the breast or nipple’ (OR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.53–0.97), ‘changes in the size of the breast or nipple’ (OR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.52–0.92), ‘unexplained weight loss’ (OR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.52–0.81), and ‘extreme generalized fatigue’ (OR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.57–0.87) (Table 3). However, screening-eligible women had a higher likelihood of not seeking medical advice for ‘discharge or bleeding from the nipple’ (OR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.04–2.56) compared to their screening-ineligible counterparts.

Association between eligibility for BC screening and seeking medical advice within a week

Screening-eligible women had a higher likelihood of seeking medical advice within a week for six out of 13 possible BC symptoms, namely ‘redness of the breast skin’ (OR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.24–2.03), ‘nipple rash’ (OR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.06–1.79), ‘changes in the shape of the breast or nipple’ (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.03–1.81), ‘changes in the size of the breast or nipple’ (OR = 1.44, 95% CI 1.10–1.88), ‘unexplained weight loss’ (OR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.14–1.75), and ‘extreme generalized fatigue’ (OR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.14–1.75) compared to their screening ineligible counterparts (Table 4).

Barriers to early presentation and eligibility for BC screening

Among screening-eligible participants, 9.9% (n = 62) acknowledged a delay in seeking medical attention upon recognizing a potential BC symptom, reporting at least one barrier to early presentation (Table 5). The most prevalent barriers to seeking medical advice for potential BC symptoms were emotional in nature, with ‘disliking the visit to healthcare facilities’ identified as the most reported barrier among screening-eligible participants (n = 38, 61.3%) and ‘feeling worried about what the doctor might find’ in the screening-ineligible group (n = 133, 57.6%). Regarding service barriers, ‘the small number of female doctors in the Palestinian Ministry of Health facilities’ was the most reported barrier in both the screening-eligible (n = 19, 30.6%) and ineligible (n = 77, 33.3%) groups. The most commonly reported practical barrier in the screening-eligible group was ‘having other things to do’ (n = 35, 56.5%), while it was ‘would think that the symptom is not something important to see the doctor for’ (n = 109, 47.2%) in the screening-ineligible group.

There was no association between eligibility for BC screening and the total number of reported barriers (Table 6). Similarly, no associations were found between BC screening eligibility and the reported number of each type of barriers, whether emotional, service-related, or practical.

Discussion

This study assessed the differences in early presentation and barriers to seeking medical advice between screening-eligible and ineligible women. The results indicate that the proportion of participants who would seek medical advice immediately varied for different BC symptoms among both groups. Emotional barriers were the most frequently reported barriers by study participants in both groups. Notably, there was no association found between eligibility for BC screening and the total number of reported barriers. Similarly, no associations were identified between BC screening eligibility and the reported number of each type of barriers, whether emotional, service-related, or practical.

Approximately half of participants in both the screening-eligible and ineligible groups expressed their intention to seek immediate medical advice for ‘lump or thickening in the breast’ and ‘nipple discharge or bleeding.’ For other BC symptoms, less than half of the participants in both groups expressed the intent for an immediate medical consultation, with ‘lump or thickening under the armpit’ identified as the most concerning symptom in both groups. This aligns with previous studies indicating that women exhibit a greater likelihood of promptly seeking medical assistance when experiencing symptoms related to a breast lump or thickening in the axilla20,23,24. Understanding the factors contributing to delays in seeking medical attention provides insights for tailored interventions, such as emphasizing other non-lump related BC symptoms in awareness campaigns. This can help reduce time intervals, leading to earlier diagnoses and lower mortality rates from BC in Palestine.

Interestingly, a study revealed that women with both lump and non-lump symptoms exhibited prolonged patient intervals compared to those with breast lump-only symptoms25. This suggests an increased tendency among women to normalize a breast lump when accompanied by additional non-lump-related breast symptoms26. It also underscores the significance of educational interventions tailored to expedite the diagnostic pathway for women presenting with non-lump symptoms. Improving the clarity of referral pathways, enhancing diagnostic services, and optimizing the limited human and infrastructure resources may contribute to more consistent and coordinated care. These measures have the potential to enhance accurate diagnoses at earlier stages and ultimately improving overall BC outcomes, especially in resource-limited countries like Palestine27.

This study revealed that screening-eligible women had a higher likelihood of promptly seeking medical advice within a week for six out of 13 possible BC symptoms. This could be attributed to better health literacy stemming from more frequent interactions with the healthcare system and the proactive health-seeking behavior encouraged by their healthcare providers28. Being aware of their eligibility for BC screening may have contributed to a greater sensitivity to potential symptoms, prompting them to seek medical advice promptly. Moreover, considering the younger age of screening-ineligible participants, it is plausible that they perceived their risk of BC to be lower and were less likely to attribute their symptoms to BC. Instead, they might have thought the symptoms would resolve on their own, contributing to the delay in seeking care. This interpretation aligns with findings from a study conducted in Egypt, where patients demonstrated a negative outlook on cancer symptoms, including a lack of awareness about BC, denial of having BC, and a belief that the mass would resolve spontaneously29. These results emphasize the significance of BC screening initiatives, highlighting their role not just in early detection but also in promoting a proactive health-seeking behavior, especially among screening-eligible women.

In this study, about 10% of participants acknowledged a delay in seeking medical attention upon recognizing a potential BC symptom, reporting at least one barrier to early presentation. Aligning with prior research30,31,32, emotional barriers were the most prevalent, with ‘disliking the visit to healthcare facilities’ emerging as the primary barrier among screening-eligible participants. Conversely, in the screening-ineligible group, ‘feeling worried about what the doctor might find’ took precedence. The emotional aspects of seeking medical care are not only individual but are also shaped by social interactions and perceptions. The patient’s social network plays a crucial role in influencing the decision to seek medical care23. This highlights the complex interplay between health, cultural, and social factors.

Additionally, despite the availability of a fully accessible and cost-free screening program8, socio-demographic and healthcare delivery barriers persist. Systemic challenges, such as limited accessibility to screening services and a lack of tailored communication strategies from healthcare professionals and families, can contribute to mistrust33. This reinforces the need for culturally sensitive healthcare approaches to improve engagement and trust in preventive care. Therefore, future BC campaigns should consider extending their focus to include men and promoting family involvement in the decision-making process, which may help in decreasing the emotional barriers and thus improve early seeking of medical advice. Furthermore, both screening-eligible and ineligible women identified the limited availability of female doctors in the Palestinian Ministry of Health facilities as the predominant service-related barrier. Consequently, prioritizing the increase in the number of female doctors becomes imperative to facilitate the early help-seeking behavior of women experiencing potential BC symptoms20. It is also important to mention that the similarities in displayed barriers between screening-eligible and screening-ineligible women as well as the lack of association between BC screening eligibility and reported number of barriers provide an opportunity to standardize future interventions aiming to mitigate those barriers.

Future directions

Collaborative efforts among healthcare providers, policymakers, and community leaders are crucial for strengthening the healthcare system, improving accessibility, and maintaining the quality of mammography services in Palestine. Future initiatives should prioritize the implementation and evaluation of culturally sensitive educational interventions and community outreach programs to enhance BC awareness and address barriers to early symptom presentation. Emphasis should be placed on communicating the significance of non-lump breast changes, highlighting the potential curability of BC when detected early, and fostering a positive perception of healthcare providers and facilities in Palestine. Extending campaigns to involve men and families in decision-making processes may further alleviate emotional barriers and enhance participation in mammography screening. Finally, efforts should be made to increase the number of female healthcare workers in order to enhance women’s comfort when receiving treatment for BC or even while undergoing screening mammography.

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of the study are the large sample size, high response rate, and broad geographical coverage. However, there are some limitations. The use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the large participant pool and representation from diverse geographical regions may have mitigated this limitation. The exclusion of individuals with medical backgrounds and those attending oncology departments may potentially have reduced the representation of participants presumed to have certain health-seeking behavior. Moreover, there could be a potential for recall and social desirability bias in self-reported data. Nonetheless, our questionnaire used neutral, non-leading questions to minimize response bias. Additionally, data collectors were trained to maintain consistency in administering surveys.

Lastly, participants’ anticipated time and perceived barriers to seeking BC care were assessed, which may differ from evaluating those aspects among patients diagnosed with the disease. We acknowledge that our cross-sectional design does not assess whether participants actually sought medical care after experiencing symptoms. To address this, future research should incorporate qualitative methods, such as focus groups or in-depth interviews, to gain deeper insights into personal and cultural barriers. Additionally, longitudinal studies using a probability sampling approach would be valuable for tracking participants’ health-seeking behaviors over time, providing a clearer understanding of their decision-making processes and long-term engagement with screening programs.

Conclusions

The inclination to seek immediate medical advice for various BC symptoms differed among screening-eligible and ineligible groups. Emotional barriers were consistently reported as the most prevalent barriers in both groups. Notably, there was no observed association between eligibility for BC screening and the total number of reported barriers. Similarly, no significant associations were identified between BC screening eligibility and the reported number of each barrier type, including emotional, service-related, or practical barriers. To address these barriers, culturally tailored educational interventions are essential and should align with the specific needs and beliefs of the Palestinian population.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Arnold, M. et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 66, 15–23 (2022).

World Health Organization. Cancer Today. https://bit.ly/42rnOmS. (Accessed on 25 May 2025).

World Health Organization. Guide to cancer early diagnosis. https://bit.ly/4aevdar. (Accessed on 25 May 2025).

Unger-Saldaña, K. Challenges to the early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in developing countries. World J. Clin. Oncol. 5, 465 (2014).

Grosse Frie, K. et al. Factors associated with time to first healthcare visit, diagnosis and treatment, and their impact on survival among breast cancer patients in Mali. PLoS ONE 13, e0207928 (2018).

Heaney, C. For One Breast Cancer Survivor in Gaza Strip, a Journey of Hardship and Hope - UNFPA Press Release. Question of Palestine https://www.un.org/unispal/document/for-one-breast-cancer-survivor-in-gaza-strip-a-journey-of-hardship-and-hope-unfpa-press-release/.

AlWaheidi, S., McPherson, K., Chalmers, I., Sullivan, R. & Davies, E. A. Mammographic screening in the occupied Palestinian territory: A critical analysis of its promotion, claimed benefits, and safety in Palestinian health research. JCO Glob. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.19.00383 (2020).

Hamshari, S. et al. Mammogram uptake and barriers among Palestinian women attending primary health care in North Palestine. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 27, 264–270 (2021).

Petro-Nustas, W. I. Factors associated with mammography utilization among Jordanian women. J. Transcult. Nurs. Off. J. Transcult. Nurs. Soc. 12, 284–291 (2001).

Almuhtaseb, M. I. A. & Alby, F. Socio-cultural factors and late breast cancer detection in Arab-Palestinian women. TPM Test Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 28, 275–285 (2021).

AlWaheidi, S. Breast cancer in Gaza-a public health priority in search of reliable data. Ecancermedicalscience 13, 964 (2019).

Elshami, M. et al. Women’s awareness of breast cancer symptoms: a national cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Public Health 22, 801 (2022).

Elshami, M. et al. Awareness of Palestinian women about breast cancer risk factors: A national cross-sectional study. JCO Glob. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.22.00087 (2022).

Elshami, M. et al. Common myths and misconceptions about breast cancer causation among Palestinian women: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 23, 2370 (2023).

Linsell, L. et al. Validation of a measurement tool to assess awareness of breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 46, 1374–1381 (2010).

Donnelly, C. et al. Do perceived barriers to clinical presentation affect anticipated time to presenting with cancer symptoms: an ICBP study. Eur. J. Public Health 27, 808–813 (2017).

Cassim, S. et al. Patient and carer perceived barriers to early presentation and diagnosis of lung cancer: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 19, 25 (2019).

Harvard Humanitarian Initiative: KoBoToolbox. https://www.kobotoolbox.org. (Accessed 25 May 2025).

Elshami, M. et al. Barriers to timely seeking of breast cancer care among Palestinian women: A cross-sectional study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 10, e2300373 (2024).

Elshami, M. et al. Breast cancer awareness and barriers to early presentation in the Gaza-strip: A cross-sectional study. J. Glob. Oncol. 4, 1–13 (2018).

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). On the occasion of the International Workers’ Day, H.E. Dr. Ola Awad, President of PCBS, presents the current status of the Palestinian labour force. https://bit.ly/3SHYv9U. (Accessed 25 May 2025).

Unger-Saldaña, K., Ventosa-Santaulària, D., Miranda, A. & Verduzco-Bustos, G. Barriers and explanatory mechanisms of delays in the patient and diagnosis intervals of care for breast cancer in Mexico. Oncologist 23, 440–453 (2018).

Shakor, J. & Mohammed, A. Women’s delay in presenting breast cancer symptoms in Kurdistan-Iraq. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 16, 1360 (2020).

Koo, M. M. et al. Typical and atypical presenting symptoms of breast cancer and their associations with diagnostic intervals: Evidence from a national audit of cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol. 48, 140–146 (2017).

Marcu, A., Lyratzopoulos, G., Black, G., Vedsted, P. & Whitaker, K. L. Educational differences in likelihood of attributing breast symptoms to cancer: a vignette-based study. Psychooncology 25, 1191–1197 (2016).

AlWaheidi, S. Promoting cancer prevention and early diagnosis in the occupied Palestinian territory. J. Cancer Policy 35, 100373 (2023).

Buawangpong, N. et al. Health information sources influencing health literacy in different social contexts across age groups in Northern Thailand Citizens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 6051 (2022).

Ismail, G. M., Abd El Hamid, A. A. & Abd ElNaby, A. G. Assessment of factors that hinder early detection of breast cancer among females at Cairo University Hospital. World Appl. Sci. J. 23, 99–108 (2013).

O’Hara, J. et al. Barriers to breast cancer screening among diverse cultural groups in Melbourne, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1677 (2018).

Magai, C., Consedine, N., Conway, F., Neugut, A. & Culver, C. Diversity matters: Unique populations of women and breast cancer screening. Cancer 100, 2300–2307 (2004).

Nadalin, V., Maher, J., Lessels, C., Chiarelli, A. & Kreiger, N. Breast screening knowledge and barriers among under/never screened women. Public Health 133, 63–66 (2016).

Baird, J., Yogeswaran, G., Oni, G. & Wilson, E. E. What can be done to encourage women from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds to attend breast screening? A qualitative synthesis of barriers and facilitators. Public Health 190, 152–159 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the study participants whose invaluable contributions made this research possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ME and MA1 contributed to the design of the study, data analysis, data interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. MA2, IA, FDU, MAMQ, IOI, RJG, HMO, NRSS, IIM, AAF, MRMH, NG, MA3, RKZ, WAA, NKM, RJM, HJAH, RAL, SNU, NAJ, RKA, SNA, BNAA, AJAK, MHD, ROT, DMA, RAM, TS, SIA, and MAE contributed to the design of the study, data collection, data entry, and data interpretation. NAE and BB contributed to the design of the study, data interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, and supervision of the work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Resources Development department at the Palestinian Ministry of Health, the Research Ethics Committee at the Islamic University of Gaza, and the Helsinki Committee in the Gaza Strip prior to data collection. The study adhered to local guidelines and regulations. Participants received a detailed explanation of the study’s objectives, emphasizing the voluntary nature of their participation. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to conducting interviews, and data confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elshami, M., Albandak, M., Alser, M. et al. Differences in seeking breast cancer care between screening eligible versus ineligible Palestinian women. Sci Rep 15, 24705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10605-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10605-x