Abstract

Machine learning has shown great potential in predicting soil properties, but individual models are often prone to overfitting, limiting their generalization. Ensemble models address this challenge by combining the strengths of multiple algorithms. This study applies a voting-based ensemble model (VEM), integrating Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and XGBoost (XGB), to gain a deeper understanding of soil type evolution, which is crucial for land management and soil conservation. The research, conducted in the Tongzhou District of Beijing, uses 5,000 sampling points selected via genetic algorithms for model training, 237 surface samples for consistency testing, and 97 profiles for field validation. The VEM demonstrates high accuracy and robustness, producing a detailed soil type map and identifying key trends in soil type evolution. This study highlights the effectiveness of ensemble models in understanding soil evolution and offers valuable insights into soil system dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil type maps provide basic information on soil types and their spatial distribution, which can be used as a key reference for land-use planning and agricultural decision-making1,2. Traditional soil type maps, primarily relying on field surveys and expert experience, suffer from insufficient sampling density and outdated data3. However, traditional soil maps contain a wealth of expert knowledge summarizing soil characteristics and reflecting soil genesis and distribution patterns4. With the advancement of computer technology and machine learning algorithms, it is now possible to utilize large-scale data such as satellite remote sensing, digital elevation models, and climate data, in conjunction with the expert knowledge provided by traditional soil maps, to establish machine learning models for predicting soil type distribution, thus creating high-precision digital soil maps5,6. This approach can overcome the limitations of traditional soil type maps in terms of sampling density, enable dynamic updating of soil type information, and greatly improve the efficiency of soil map production7.

Machine learning models can effectively process and analyze large volumes of complex data, significantly improving the accuracy and efficiency of soil mapping. At the same time, researchers can utilize these efficient tools to analyze soil characteristics8. Soil distribution is influenced by various environmental factors and exhibits high complexity9. Machine learning models are capable of understanding these complex datasets and extracting the driving factors that affect soil properties10,11. Currently, many researchers are dedicated to employing high-quality machine learning models for soil mapping and conducting in-depth studies in different areas of soil science. For example, Padarian et al. demonstrated how convolutional neural network (CNN) models can enhance the prediction accuracy of DSM, breaking through the limitations of traditional DSM models that typically rely on point observations cross-calibrated with spatial covariates12. The results showed that the CNN model reduced errors by 30% in this study. These machine learning models, whether based on existing frameworks or developed by researchers, demonstrate applicability in various directions within soil science13.

However, individual machine learning models often have limitations; a single model may overfit specific features in the training data, leading to poor generalization to new data14. Moreover, soil properties are typically influenced by multiple factors, and single models may struggle to address the complexity and diversity of soil attributes15. To overcome these challenges, some studies have adopted ensemble models, which integrate several distinct machine learning algorithms, overcoming the limitations of single models and leveraging their strengths to improve prediction accuracy and reliability16,17. This approach enhances model generalization since different models may perform better under varying soil types and environmental conditions18. Researchers have made significant progress using ensemble models to study soil properties. For instance, Song et al.19developed an ensemble model that effectively mapped the three-dimensional soil organic carbon (SOC) distribution in China, achieving a 12.6% improvement in accuracy compared to individual machine learning models. Pham et al.20designed an ensemble framework for expansive soil slope stability modeling, utilizing 2,000 data points on slope protection structure issues, which improved prediction accuracy by 15% over individual models. Zhang et al.21 implemented a hierarchical ensemble model that integrated multiple pedotransfer functions (PTFs) to estimate global soil water retention using a dataset of 10,000 soil profiles, improving model accuracy by 20% compared to individual PTFs.

Although machine learning ensemble techniques have been widely adopted to enhance the generalization capability of DSM, few studies have leveraged heterogeneous model integration to investigate the dynamic evolution of soil types by synergizing the distinct strengths of diverse algorithms22. Existing research predominantly focuses on predicting static soil properties, while neglecting the dynamic mechanisms underlying soil type transitions driven by the interplay of environmental changes and intrinsic pedogenic processes23. This gap is particularly pronounced under the Chinese Soil Taxonomy, where soil classification is inherently tied to five soil-forming factors and requires the integration of multi-source data to decode evolutionary patterns24. However, current ensemble approaches exhibit limited efforts to harmonize heterogeneous models with region-specific environmental drivers. These limitations hinder the ability of ensemble methods to unravel soil evolution mechanisms and inform sustainable land management practices25,26. Based on the high performance of ensemble models, they can dynamically interpret the spatial distribution patterns and key driving mechanisms of soil evolution within the unique context of soil science in China. This approach allows for the quantification of the interactions between anthropogenic pressures and intrinsic soil formation processes, offering insights into the mechanisms behind soil type evolution, rather than simply improving the prediction accuracy of soil types.

In this study, a voting-based ensemble model (VEM) was developed, integrating three algorithms: Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and XGBoost (XGB). By combining the predictions of each base model through a weighted voting mechanism, the study aimed to gain a deeper understanding of soil evolution in the Tongzhou District, Beijing. The study used 5,000 sampling points selected through genetic algorithms and consistent environmental covariates, comparing the mapping accuracy of the RF, SVM, XGB, and VEM models. Comprehensive evaluation was conducted using confusion matrices and field validation data, along with an additional consistency check using 237 field-collected analytical samples. The prediction results were further analyzed to uncover the key driving factors behind soil evolution in the region, providing valuable insights into the processes of soil change. The objectives of this study are: (1) To design an ensemble model that overcomes the limitations of single models and enhances the accuracy and stability of soil type predictions. (2) To quantify the improvement in accuracy and stability that ensemble models can achieve compared to individual machine learning models. (3) To leverage high-precision mapping results and integrate multi-source data to uncover the spatial distribution patterns and key driving mechanisms of soil dynamic evolution.

Materials and methodology

Research area

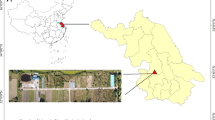

As shown in Fig. 1, Tongzhou District, located in the southeast part of Beijing, China, is part of the North China Plain. It is situated between latitudes 39°36’ and 40°02’ N, and longitudes 116°32’ and 116°56’ E, spanning 36.5 km east-west and 48 km north-south, covering an area of 907 km². The terrain of Tongzhou District is predominantly flat, characterized by plains27. Due to its stable and flat topography, the terrain is conducive to water infiltration and retention in the soil, which reduces soil erosion and allows the soil to better retain nutrients and moisture. The soil development process in this area is relatively uniform, leading to the formation of typical plain soil structures. Tongzhou District is located in a temperate monsoon climate zone, where the four seasons are distinct, and the climatic conditions have a significant impact on soil formation. In the temperate monsoon climate, concentrated rainfall in summer and high temperatures promote the decomposition of organic matter and the accumulation of soil nutrients, while the cold and dry winter conditions reduce soil moisture evaporation, contributing to the stability of soil structure. These climatic characteristics result in generally fertile soils in Tongzhou District, making them well-suited for agricultural production. The surface of Tongzhou District is continually covered with thick Quaternary and Tertiary loose sediments, forming the basis for the modern alluvial fan plains and the low-lying plains. As a pilot area for China’s Second National Soil Survey, the soil type map of Tongzhou District was completed under the leadership of Chinese soil scientist Xi Chengfan in 1980, providing highly reliable soil information. During the Second Soil Survey, Tongzhou District was reported to have four soil types: Fluvo-aquic soil, Cinnamon soil, Bog soil, and Aeolian soil. China’s Third National Soil Survey commenced in 2022. According to the results of China’s Third National Soil Survey, the district consists of 3 soil group, 8 subgroup, 13 soil genus, and 42 soil species, including Fluvo-aquic soil, Cinnamon soil, and Aeolian soil, with Fluvo-aquic soil being the dominant soil type in Tongzhou District, and the bog soil has completely disappeared. Each soil species has been assigned a unique code to facilitate subsequent analysis. The details of the soil classification system for Tongzhou District are presented in Table S1.

Study Area and Calibration Soil Type Map (Table S1 lists the specific meanings of the codes shown in the figure, providing explanations of the correspondence between soil type codes and their respective soil type names).

Processing of environmental covariates

Environmental covariates are crucial auxiliary tools for soil mapping using models28. Different soil types are often associated with varying environmental conditions, and selecting appropriate environmental covariates can enable more suitable model-based mapping, thereby enhancing the understanding of soil spatial distribution29,30. We selected environmental covariates including groundwater depth, parent material, texture, distance to water bodies, land cover type, elevation, Land Surface Temperature (LST), and Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI). The conventional soil maps, texture, elevation, groundwater depth, distance to water bodies systems, and other datasets were obtained from the National Science & Technology Infrastructure of China (http://www.geodata.cn). Parent material information was sourced from the 1:50,000 geological map of the area. RSEI, LST and land cover type data were acquired from Landsat series data on Google Earth Engine (GEE) after undergoing several processing steps. RSEI is a composite index calculated by integrating multiple remote sensing indicators, including Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI), and Normalized Difference Bare Soil Index (NDBSI). The RSEI is calculated by coupling four indicators—greenness, dryness, wetness, and heat—into a principal component analysis, with the first principal component serving as the RSEI value. This index is used to assess the ecological environment of a region. The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data had a resolution of 12.5 m, while other environmental covariates, such as LST, land cover, and RSEI, had a resolution of 30 m. The data related to time were annual results processed in 2022. In the model prediction process, this study first extracted the environmental variable features corresponding to sample points from the environmental raster data. After standardization and missing value imputation, feature engineering was applied to enhance the data. The feature engineering included nonlinear transformations of numerical features, such as logarithmic and square root transformations, and the generation of interaction terms between features as well as rolling statistics to better capture the underlying patterns in the data. The maps in this manuscript were generated using R (version 4.2, URL: https://www.r-project.org/), ArcGIS (version 10.8, URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis), and Python (version 3.4, URL: https://www.python.org/).

Sample data processing

Sample points for mapping

A typical method for updating soil maps is to extract expert knowledge from calibration soil type Maps using data mining models, design sampling methods through auxiliary environmental variables, and then employ machine learning models for mapping31,32. The selection of sample points has an important impact on the accuracy of the subsequent analysis. In order to improve the representativeness of the sample points within the study area, this paper utilizes a genetic algorithm (GA) to select the optimal set of sample points from the environmental covariates33. Genetic algorithms can efficiently handle large-scale data and reduce the time and resources required in the sample selection process compared to traditional manual or experience-based sample point selection methods34. This is particularly beneficial for large-scale or multidimensional data analysis, enabling the rapid generation of optimized sample point sets. Genetic algorithms can combine multiple optimization objectives in the fitness function, e.g., in this paper both representativeness (variance) and spatial distributability (distance) of sample points are considered. By weighing these objectives, the genetic algorithm is able to find an optimal solution that balances each requirement, thus providing a sample point selection scheme that integrates multiple factors. In this way, the GA can guide the search process toward evolving such high-quality sample sets35. The fitness function is defined as follows:

Here, \(\:{w}_{1}\) and \(\:{w}_{2}\) are the weights, where \(\:{w}_{1}\)=1 and \(\:{w}_{2}\)=0.5 are chosen to give greater influence to variance while still considering spatial distribution, without allowing the latter to dominate.\(\:\:{m}_{1}\) represents the representativeness score, which is the variance of the environmental covariates of the selected sample points, and \(\:{m}_{2}\) represents the distance score, which is the spatial distance between the selected sample points. In this paper, the population size, the maximum number of iterations, and the number of runs are set to 150, 150, and 50, respectively. After the GA runs are completed, the set of sample points corresponding to the optimal solution is selected and the top 5000 sample points are further filtered based on the fitness score. In the model prediction process, to address the class imbalance issue, the study employed Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) to oversample the minority class samples, while also incorporating random undersampling to ensure the balance of the dataset. The SMOTE strategy generates new samples of the same class based on the sample size of each category, thereby balancing the number of samples between the smallest and largest classes.

Field calibration sample points

To fully demonstrate the accuracy of the model, the precision of mapping was evaluated using 97 actual field verification points, thereby comprehensively assessing the mapping standard of the model, classified by experienced soil scientists. In designing the routes, we fully considered uniformity and representativeness, ensuring that each soil type had verification points and were evenly distributed throughout the study area. Priority was given to choosing field verification sample points at the junctions of soil type patches, unique terrains, areas with significant topographic changes, and potential change plots. This was done to thoroughly evaluate the spatial distribution rationality of each soil type and the predictive level of the mapping model in high probability soil evolution areas. The sample points are shown in Fig. 2b.

Sample points for consistency test

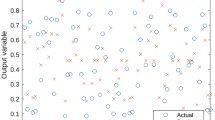

Different soil types exhibit varying physical and chemical properties21,36. For example, certain soil types have specific pH ranges, and the classification and naming of soil types often reflect surface soil organic matter, soil texture, or soil salinity content37. By overlaying surface soil physical and chemical information, such as organic matter and pH, the consistency between soil types and key soil attributes can be examined, which helps to verify the accuracy of soil maps38. The sample points used for soil property mapping in this study are derived from the results of the Third National Soil Survey of China, totaling 237 sample points, including 235 surface samples and 2 profile samples. The soil samples collected in the field were sent to specialized testing laboratories that were uniformly selected by the National Office of the Third Soil Survey. Standardized pre-treatment was carried out, and batch testing of physical, chemical, and other indicators of the soil samples was performed. The distribution of sample points is shown in Fig. 2b. Mapping of attributes such as organic matter, pH, and total ion content was performed using Random Forest (RF) with the same set of environmental covariates. For organic matter, pH, and total ion content, the optimal model was obtained when the mtry was set to 2, meaning that 2 features were randomly selected at each split for calculation. At this point, the model achieved its best performance, as indicated by the result in Fig. 2a.

Mapping model

Ensemble learning is one of the most important techniques in machine learning today. By training multiple models and integrating their predictions, it can effectively improve the model’s generalization ability and enhance the stability and accuracy of predictions39,40. This improvement in accuracy primarily stems from the ensemble model’s ability to combine the strengths of multiple base learners, reducing the model’s dependence on the bias of specific algorithms41,42. Each base learner has a different approach to understanding and processing the dataset, so they may produce different errors in predictions43. Through ensemble learning, these errors can counterbalance each other, thus improving overall predictive accuracy44.

This study constructed a Voting-based Ensemble Model (VEM), consisting of three base learners: Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and XGBoost (XGB). RF is a forest model containing multiple decision trees, capable of handling high-dimensional data and avoiding overfitting. SVM is a binary classification model with strong classification capability for linearly separable data. XGB, based on gradient-boosted decision trees, can effectively handle high-dimensional data and nonlinear relationships and automatically addresses issues like feature selection and overfitting avoidance. During the training process of each base model, cross-validation was performed to ensure the robustness of each model across different datasets. The predictions from each base model were weighted based on their performance in cross-validation. Specifically, a composite score for each model was calculated based on six evaluation metrics: F1 score, precision, recall, prediction confidence, prediction stability, and class separability. The weight distribution was as follows: F1 score 30%, precision 20%, recall 20%, prediction confidence 15%, prediction stability 10%, and class separability 5%. Through this weighted voting strategy, the ensemble model combines the advantages of multiple base models, overcoming the biases of individual models and improving overall predictive performance.

Additionally, a dynamic class weight allocation mechanism was introduced in the weighted voting process. This mechanism dynamically adjusts the weights of each class based on the similarity between classes. The prediction results for similar classes are penalized to reduce interference between predictions for similar classes, thereby ensuring more accurate classification. This strategy effectively prevents excessive cross-prediction when there is significant similarity between classes.

To further enhance prediction reliability, an adaptive voting mechanism was implemented, dynamically selecting the optimal model based on the prediction confidence of each model. When a model’s prediction confidence exceeds 0.9, its prediction results are prioritized and given higher weight in the weighted voting. Conversely, when a model’s confidence is below 0.9, its weight in the voting process is reduced. This mechanism allows predictions with higher confidence to be prioritized, improving the overall stability of the predictions.

For small sample categories (categories with fewer than 5 samples), where insufficient sample data may lead to overfitting or instability in predictions, the study specifically used the RF model for these categories. RF, known for its strong stability and robustness when handling small sample data, was employed to ensure accurate predictions for these small sample categories.

Evaluation of soil map accuracy

The assessment of model performance is a crucial part of soil type mapping, as it helps understand the accuracy and reliability of the model45. We evaluate the model results using Accuracy and Kappa coefficient. Cohen’s Kappa is a widely used statistical metric for evaluating the performance of classification models. The formula for calculating the Kappa coefficient is as follows:

Where \(\:{p}_{o}\) represents the observed accuracy, and \(\:{p}_{e}\) represents the accuracy expected by chance under random classification.

To avoid spatial autocorrelation affecting model training, this study employed a Spatial Cross-Validation (SCV) method. This method ensures that training and test sets in each fold of the cross-validation are spatially independent by setting a buffer distance46,47. Specifically, the sample points in the test set are kept at a certain spatial distance from those in the training set, avoiding overlap between geographically close samples in the training and validation sets, thus ensuring spatial independence during model training. After testing different buffer distances (500 m, 1000 m, and 2000 m), a buffer distance of 2000 m was chosen as the optimal value. The remaining points are used as training samples. This ensures that, during each cross-validation fold, the test points are randomly selected and that the samples in the test set are spatially independent of the training set48.

Results

Soil map accuracy analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the comparison between models in terms of accuracy and Kappa coefficient highlights the effectiveness of the VEM. VEM outperformed individual models, achieving the highest accuracy of 0.783 and a Kappa coefficient of 0.753. In comparison, RF, XGB, and SVM achieved lower accuracy and Kappa scores. These results suggest that integrating multiple base learners in VEM improves both prediction accuracy and consistency, particularly when handling complex data with spatial dependencies and class imbalances. The superior performance of VEM reflects the advantages of ensemble methods in enhancing model reliability and predictive power.

These data analysis results clearly indicate that by combining the strengths of different machine learning algorithms, the VEM significantly outperforms individual algorithm models in the precise classification and prediction of soil maps. The improvement in accuracy is attributed to the VEM effectively combining the strengths of multiple base models. Through the weighted voting mechanism, the model dynamically adjusts the weight of each base model based on its performance, fully leveraging their strengths and avoiding the biases of individual models. The dynamic class weight allocation mechanism reduces interference between similar classes, ensuring more precise classification. The adaptive voting mechanism adjusts model weights based on prediction confidence, prioritizing predictions from models with higher confidence, thus enhancing stability and accuracy. Additionally, for small sample categories, Random Forest was used to prevent overfitting and ensure accurate predictions. These mechanisms collectively enhance the overall accuracy of the model, ensuring superior performance on complex datasets. This capability is particularly important in the field of soil science, where soil data often contains a large number of variables and complex spatial relationships.

Comparisons of mapping results

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the RF model excels in handling complex spatial data, particularly when classifying soil types with high diversity. However, it shows limitations in identifying certain specific soil types. In contrast, the SVM model demonstrates good generalization capability for large-area soil types but falls short in processing small-area soil type data, resulting in lower prediction performance compared to the other three models. The XGB model exhibits strong capabilities in managing complex datasets, with overall mapping results similar to those of RF and VEM. However, it struggles with finer details. The VEM, on the other hand, performs exceptionally well in handling soil type boundaries and identifying small area soil type variations. The soil maps generated by VEM show higher coherence and consistency in spatial distribution. This superiority stems from VEM’s ability to integrate the strengths of RF’s robust spatial data processing, SVM’s generalization capability, and XGB’s proficiency in handling large datasets. Consequently, VEM outperforms any single model, indicating that by combining the different advantages of these models, VEM can more effectively address the complexity and diversity of soil data.

Soil map of Tongzhou District under different mapping models (Table S1 lists the specific meanings of the codes shown in the figure, providing explanations of the correspondence between soil type codes and their respective soil type names).

As shown in Fig. 2b, no sampling points were set in the main urban area of Tongzhou District. In these areas, the absence of sampling points may increase prediction uncertainty, possibly due to the model’s interpretation of environmental factors and their complex relationships with soil types. In the urban areas lacking sampling points, each model exhibits significant differences in soil type prediction. The prediction in these areas depends on how well each model leverages spatially proximate sampling point information and environmental covariates. In urban areas, particularly at the urban fringe, human activities strongly influence soil types, potentially leading to significant discrepancies between prediction results and actual conditions.

Overall, the VEM model exhibits a more refined and coherent spatial distribution pattern in predicting urban soil types compared to single models (RF, SVM, XGB). This is likely due to the ensemble model’s ability to combine the strengths of multiple models, capturing the complex soil distribution characteristics in urban areas more effectively. For example, regions that might appear fragmented or overly dispersed in predictions by RF, SVM, and XGB are more accurately and consistently predicted and presented in the VEM model.

Evolution in soil types

In Tongzhou District, the verification process identified a total of 3 soil groups, 8 subgroups, 13 soil genera, and 42 soil species. After mapping, it was found that medium loam wet-flush soil, medium loam bottom clay deaquic soil, clay with sand calcareous fluvo-aquic soil, medium loam mud sandy cinnamon soil, and medium loam bottom clay mud sandy cinnamon soil were not displayed on the newly compiled soil map, indicating that these five soil types have transitioned to other soil types in Tongzhou District. Before indoor verification, medium loam wet-flush soil was preliminarily identified as medium loam bog soil, but the mapping results showed that the disappearance of bog soil in Tongzhou District did not convert into medium loam wet-flush soil, which explains the absence of this soil type in the model’s predicted map. According to the results of the second national soil survey in China 40 years ago, medium loam bottom clay deaquic soil, clay with sand calcareous fluvo-aquic soil, medium loam mud sandy cinnamon soil, and medium loam bottom clay mud sandy cinnamon soil are sparsely distributed in Tongzhou District. With urban development and changes in land use structure, these soil types have been converted into other soil types. The changes in the area of soil types between the second national soil survey and the newly compiled soil map in Tongzhou District are shown in Table 1. Due to the inclusion of urban areas in the verified soil map, there is a discrepancy in the total area compared to the newly compiled soil map. Ultimately, Tongzhou District has a total of 3 soil groups, 7 subgroups, 12 soil genera, and 37 soil species.

Discussion

Field verification

Field verification of accuracy is crucial for assessing the practical value of soil type prediction models. This validation method involves verifying the predicted soil types by collecting ground-truth samples in the field to test the accuracy of the models under real-world conditions. Such validation based on real-world data provides a more accurate reflection of the model’s performance compared to relying solely on theoretical or simulated data.

The accuracy of the calibration soil type map is 79.38%, while the accuracy of the SVM model is only 81.67%, which is slightly higher than the calibration soil type map. This may be due to its limitations in handling high-dimensional data and complex spatial relationships. The XGB model achieved an accuracy of 86.83%, which could be attributed to the uneven sample distribution and the complexity of the field terrain, which limited its predictive capability. In contrast, the RF performed significantly better, with an accuracy of 88.35%, surpassing the calibration soil type map. This improvement may be attributed to RF’s robust handling of large-scale and multivariate spatial data, using multiple decision trees to improve prediction accuracy and stability. The highest accuracy was achieved by the VEM, which reached 93.75%. This significantly higher accuracy compared to other models indicates that the VEM effectively handles the complexity and diversity of soil type prediction by combining the strengths of multiple algorithms.

Results of the consistency analysis

Different types of soil develop a series of unique physical and chemical characteristics during their formation, influenced by their origin, formation conditions, and long-term exposure to factors such as climate, biology, and topography49. Aeolian soil, for instance, is a loose, immature soil with only A-C horizons, formed in arid and semi-arid regions on sandy parent material. It is at the initial stage of soil development, with weak soil-forming processes, consisting mainly of fine sand that can easily be moved by the wind50. The pH of aeolian soil is slightly alkaline, ranging between 8 and 951. As the aeolian soil transitions to the fixed aeolian soil stage, vegetation continues to develop, with coverage increasing to over 30%52. The biological soil-forming processes become more evident, and the soil profile further differentiates, leading to the formation of a thicker crust or humus-stained layer. This stage sees the accumulation of organic matter, giving the soil a certain level of fertility, which can further develop into the corresponding zonal soil53,54. In Tongzhou District, sand meadow fixed aeolian soil exists, as shown in Table 2. The average pH of sand meadow fixed aeolian soil in Tongzhou District is 8.22, meeting the pH consistency requirements.

Cinnamon soil is a type of semi-leached soil that forms under warm temperate, semi-humid monsoon climates and in environments characterized by arid forests and shrub-grass steppe vegetation55. It develops through processes of clayification and calcification, resulting in a clay-enriched B horizon and the accumulation of CaCO3 (pseudo-mycorrhizae) at certain points within the soil profile. The soil tends to be neutral or slightly acidic56. In the Tongzhou District, both aquic cinnamon soil and developed cinnamon soil are present. Aquic cinnamon soil, influenced by groundwater, displays rust spots or iron-manganese nodules in the lower part of the profile, and it is slightly alkaline, with a soil pH greater than 7.0. As shown in Table 2, the pH of aquic cinnamon soil areas is slightly alkaline, which meets consistency requirements. Developed cinnamon soil, found in the warm temperate semi-humid region, is subject to severe erosion, leading to poorly developed soil profiles that are shallow and contain numerous gravel or rock fragments, making biological enrichment challenging. In this study, the RSEI is used to represent the degree of biological enrichment. As indicated in Table 2, the RSEI value for developed cinnamon soil areas in Tongzhou District is only 0.43, the lowest among all subtypes, indicating a low degree of biological enrichment, which meets consistency requirements57.

Fluvo-aquic soil is a semi-hydromorphic soil that forms under the influence of groundwater, characterized by a profile structure that includes a humus layer (cultivated layer), an oxidation-reduction layer, and a parent material layer56. In the Tongzhou District, fluvo-aquic soil, dehumidified soil, wet-flush soil, and salinized fluvo-aquic soil are present. Fluvo-aquic soil, developed on the sloping plains of alluvial plains transitioning from gentle hills to depressions, is generally neutral to slightly alkaline. As shown in Table 2, the pH levels in fluvo-aquic soil, dehumidified soil, and wet-flush soil regions are slightly alkaline, meeting pH consistency requirements.

Dehumidified soil, a type of fluvo-aquic soil with leaching and deposition characteristics, represents a transitional type from fluvo-aquic soil to adjacent non-hydromorphic or semi-hydromorphic soils. It is typically found in relatively elevated terrains such as gentle hills on plains, natural levees of ancient river channels, and high terraces, with a deeper groundwater Table58. Wet-flush soil, characterized by gleying features, is a transitional type from fluvo-aquic soil to bog soil. The average elevation of dehumidified soil is relatively high, while that of wet-flush soil is relatively low, satisfying elevation consistency tests59.

Salinized fluvo-aquic soil is a type of fluvo-aquic soil in which the surface layer’s soluble salt concentration reaches salinization thresholds. It represents a transitional type from fluvo-aquic soil to saline soil and is distributed in relatively low-lying or marginal areas of alluvial plains24. It often forms a mosaic distribution with fluvo-aquic soil and wet-flush soil. In addition to the primary soil-forming processes of fluvo-aquic soil, it also undergoes salinization. As shown in Table 2, the total ion content in salinized fluvo-aquic soil is the highest. The sample data from this region indicate the presence of sulfate-dominated salinization. Specifically, the equivalent ratio of sulfate ions (SO₄²⁻) to chloride ions (Cl⁻) in the soil is 3.82:1.29, exceeding 1, confirming its classification as sulfate-salinized fluvo-aquic soil, in line with consistency tests. Ion data from other sampling points in the Tongzhou District, as shown in Table S2, do not meet the conditions for saline soil.

Causes of soil type evolution

The disappearance of bog soil

In the past, bog soil in Tongzhou developed in low-lying areas with long-term water accumulation and under hydrophilic vegetation. As a result, bog soil was primarily distributed along riverbanks and in local depressions formed by human excavation60. For bog soil to form, the groundwater level must be within 1 m of the surface. The groundwater level in Tongzhou’s alluvial plain was historically 1.5 to 2.0 m, while in the low-lying alluvial plain, it was 0.5 to 1.0 m, and in transitional depressions, it was 0.5 to 1 m—conditions suitable for bog soil formation61. However, following China’s reform and opening-up, urban development in Tongzhou has led to increased groundwater extraction, causing a decline in the water table. Additionally, urbanization has resulted in the expansion of impervious surfaces, disrupting the complete water cycle and further lowering the groundwater level. The increase in impervious surfaces has also altered the local microclimate in Tongzhou, with changes in average precipitation and other conditions making it difficult for organic matter to accumulate, leading to changes in soil types. According to the 2020 groundwater depth data in Tongzhou, the maximum groundwater depth reached 3.1 m, which is no longer conducive to the development of bog soil. Moreover, Tongzhou has been significantly impacted by human activities. These activities have altered the physical and chemical properties of bog soil, leading to its evolution and eventual disappearance.

The disappearance of cinnamon soil

In the western part of Tongzhou, within the remnants of gently sloping hills on the edge of the Quaternary alluvial fan, cinnamon soil developed from loess-like parent material. The higher elevation and good drainage conditions of these areas made them conducive to the formation of cinnamon soil. At the edge of the alluvial fan or in locally flat, low-lying areas, the terrain is gentle with slight slopes, and groundwater influences the lower parts of most cinnamon soils to varying degrees, thus playing a role in the modern soil-forming processes62. Due to Tongzhou’s location on the edge of the alluvial fan, cinnamon soil exhibits transitional characteristics towards fluvo-aquic soil in the plain areas. The local topography and groundwater levels significantly affect the development of cinnamon soil. In the stabilized dune areas on the alluvial plain, where the terrain rises 3–8 m above the surrounding plain, relatively stable soil development conditions exist, making these areas the main but scattered distribution zones for developed cinnamon soil24. However, because the terrain of the alluvial fan edge gradually transitions to the plain, aquic cinnamon soil occupies a larger area within the distribution range of cinnamon soil, while cinnamon soil only appears sporadically in locally elevated areas. Human activities, such as land leveling and excavation, have disrupted the natural soil profile configuration by removing the topsoil and exposing the subsoil, thereby altering the natural environment required for cinnamon soil formation. Additionally, the lowering of the groundwater table has contributed to the transformation of cinnamon soil into other soil types.

The increase in the distribution of Wet-Flush soil

As shown in Fig. 5, in the transition areas between the western edge of the alluvial fan and the low-lying alluvial plain in Tongzhou District, the gradual elevation of the terrain due to the continuous infilling and silting of sediments has led to a relative lowering of the groundwater table and a significant reduction in the extent of seasonal waterlogging. The soil has long moved away from marshy conditions and has been developing towards fluvo-aquic soil, now referred to as wet-flush soil. The figure also indicates that in the plain areas, river flooding, variations in flow velocity, and the differing sedimentation processes caused by water sorting have resulted in multiple changes in river courses and interbedded deposits. These processes have led to various sediments frequently overlapping, creating interlayers of sand and clay. This directly affects the dynamics of soil water and salt content, as well as the degree of soil development, resulting in a mosaic distribution of different soil types. The relatively low terrain at the edges of the transition areas is the main distribution zone for wet-flush soil. Even in slightly elevated areas within the plains, these locations are still considered relatively low-lying in terms of overall terrain trends63.

The decrease in the distribution of salinized Fluvo-Aquic soil

In the past, the southern region of Tongzhou had scattered distributions of salinized fluvo-aquic soil, particularly at the margins of transition areas between the edges of low-lying depressions and the expansive plains. The formation of this soil type was closely related to a higher groundwater table and intense evaporation. In these southern regions, the groundwater level was generally higher than in typical fluvo-aquic soils, and the soil texture tended toward sandy loam. Under poor drainage conditions, this made the soil more prone to salinization64. However, due to effective long-term water resource management, land use planning, land reclamation, and soil improvement measures in Tongzhou District, the accumulation of salts in the surface layers has been significantly reduced. The lowering of the groundwater table has further improved the soil environment, leading to the transformation of salinized soil into other soil types.

The decrease in the distribution of aeolian soil

Aeolian soil was primarily distributed along rivers and ancient riverbanks, where it was transported by wind and accumulated in dune-like formations across the plains. Along the riverbanks, aeolian soil often exhibited a parallel, band-like distribution or accumulated on the inner edges of river meanders65. In some areas along the river, larger expanses of aeolian soil were found. Additionally, aeolian soil often accumulated near villages, forming dune-like structures that rose 2–3 m above the surrounding plains and extended in ridges along the prevailing wind direction. However, following extensive agricultural land development and comprehensive planning and management efforts, much of the aeolian soil has been leveled and converted into basic farmland or forest land. As the terrain in aeolian soil distribution areas gradually flattened, these soils began transitioning into sand fluvo-aquic soil. The reduction in aeolian soil in Tongzhou District reflects this evolution, with the land predominantly transforming into sand calcareous fluvo-aquic soil, consistent with the natural progression of aeolian soil.

Distribution of soil sections

The soil distribution in Tongzhou is significantly influenced by geomorphology, topography, and hydrogeological conditions, leading to a highly varied soil distribution across different regions. The micro-scale distribution patterns of soil types are also quite pronounced. Human activities such as irrigation, drainage, fertilization, and land leveling have further altered the soil properties, making the distribution of soils more complex. Tongzhou is located in a warm temperate semi-humid region on the edge of the Beijing alluvial fan, including a large alluvial plain in the southeast that slopes toward the southeast. The western part, being at the edge of the alluvial fan, has higher terrain and is the primary distribution area for cinnamon soil. In contrast, the southeastern alluvial plain, with relatively flat terrain, is primarily influenced by sediment type, groundwater activity, and human cultivation, making it the main distribution area for fluvo-aquic soil. Due to the sloping terrain, variations in local elevation and hydrological conditions lead to differing soil distribution patterns. As shown in Fig. 6, the extensive overlap and widespread distribution of different soil types across latitudes, longitudes, and elevations suggest that their spatial patterns are influenced by a complex interplay of environmental factors. It is evident that sand calcareous fluvo-aquic soil and loam calcareous fluvo-aquic soil have the broadest distribution, with light loam bottom clay calcareous fluvo-aquic soil being more densely distributed in the central part of Tongzhou. The areas marked 15–18 and 41 represent the distribution of cinnamon soil, all located at relatively higher elevations. The areas marked 1–6 represent the distribution of dehumidified soil, which is found in relatively high and higher elevation areas.

Limitations and future work

The results of this study not only demonstrate the potential of ensemble learning in improving soil type prediction accuracy but also emphasize the importance of integrating multiple machine learning algorithms. By leveraging the strengths of different models, this approach exhibits significant advantages in enhancing predictive accuracy, managing uncertainties, and improving robustness, thereby providing more detailed soil information and contributing to a better understanding of soil evolution.

However, this study has some limitations and also provides new directions for future research. Firstly, one of the main limitations of this study is the size of the study area. The current study was conducted in a specific, limited area, which may limit the generalisation ability of our model66. Soil types and environmental conditions may vary significantly from region to region; therefore, the validity of our model in other regions has not been validated67. In order to improve the generalisation ability and applicability of the model, future research should consider testing and validating the model in a wider and diverse geographical area45.

Regarding the direction of future research, considering the potential of machine learning in soil mapping, exploring different ensemble methods would be a valuable endeavour. The current model employs a voting integration strategy, but other ensemble techniques, such as stacking and blending, may provide superior performance40. Stacking methods involve combining the predictions of several different machine learning models, while blending incorporates a meta-learner to optimise the final prediction during the model integration process. Future research could explore these different ensemble techniques to determine which combination best suits the complexity and diversity of soil types68. Additionally, while deep learning models have demonstrated advantages in large-scale soil mapping, their application here was constrained by the limited sample size and the need for interpretability in soil evolution analysis12. Future studies will incorporate CNN-based architectures with expanded datasets to evaluate their comparative performance in dynamic soil type prediction18. This may involve the development of more flexible models that can easily integrate new data sources and environmental indicators to reflect changes in the environment in real time69.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a VEM integrating RF, SVM, and XGB algorithms in predicting soil types and decoding their evolutionary dynamics in Tongzhou District, Beijing—a rapidly urbanizing region within the North China Plain. The VEM achieved superior accuracy, stability, and spatial coherence compared to individual models, particularly in resolving small-area soil boundaries and transitional zones. Crucially, the model revealed region-specific soil transitions aligned with China’s pedological framework. These findings underscore how the VEM synthesizes localized environmental drivers and anthropogenic pressures to quantify soil evolution under the Chinese Soil Taxonomy. For instance, the model linked salinized fluvo-aquic soil reduction to land reclamation policies, demonstrating its utility in evaluating conservation measures. While the VEM’s performance is context-dependent, its framework—integrating legacy soil surveys, genetic algorithm-optimized sampling, and heterogeneous model fusion—provides a replicable template for analyzing soil transitions in other regions governed by distinct classification systems.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ma, Y., Minasny, B., Malone, B. P. & Mcbratney, A. B. Pedology and digital soil mapping (DSM). Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 70, 216–235 (2019).

Hendriks, C. M. J. et al. Introducing a mechanistic model in digital soil mapping to predict soil organic matter stocks in the Cantabrian region (Spain). Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 72, 704–719 (2021).

Heung, B. et al. An overview and comparison of machine-learning techniques for classification purposes in digital soil mapping. Geoderma 265, 62–77 (2016).

Minasny, B. & McBratney Alex. B. Digital soil mapping: A brief history and some lessons. Geoderma 264, 301–311 (2016).

Lagacherie, P. et al. How Far can the uncertainty on a digital soil map be known? A numerical experiment using pseudo values of clay content obtained from Vis-SWIR hyperspectral imagery. Geoderma 337, 1320–1328 (2019).

Minasny, B. et al. Soil. Science-Informed Mach. Learn. Geoderma 452, 117094 (2024).

Arrouays, D., Poggio, L., Guerrero, S., Mulder, V. L. & O. A. & Digital soil mapping and globalsoilmap. Main advances and ways forward. Geoderma Reg. 21, e00265 (2020).

Ivushkin, K. et al. Global mapping of soil salinity change. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111260 (2019).

Wadoux, A. M. J. C., Brus, D. J. & Heuvelink, G. B. M. Sampling design optimization for soil mapping with random forest. Geoderma 355, 113913 (2019).

Mousavi, S. R., Sarmadian, F., Omid, M. & Bogaert, P. Three-dimensional mapping of soil organic carbon using soil and environmental covariates in an arid and semi-arid region of Iran. Measurement 201, 111706 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Digital mapping of soil organic carbon density in China using an ensemble model. Environ. Res. 231, 116131 (2023).

Padarian, J., Minasny, B. & McBratney, A. B. Using deep learning for digital soil mapping. SOIL 5, 79–89 (2019).

Mulder, V. L., de Bruin, S., Schaepman, M. E. & Mayr, T. R. The use of remote sensing in soil and terrain mapping — A review. Geoderma 162, 1–19 (2011).

Choi, R. Y., Coyner, A. S., Kalpathy-Cramer, J., Chiang, M. F. & Campbell, J. P. Introduction to machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning. Transl Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 14 (2020).

Tajik, S., Ayoubi, S. & Zeraatpisheh, M. Digital mapping of soil organic carbon using ensemble learning model in Mollisols of hyrcanian forests, Northern Iran. Geoderma Reg. 20, e00256 (2020).

Sakhaee, A., Gebauer, A., Ließ, M. & Don, A. Spatial prediction of organic carbon in German agricultural topsoil using machine learning algorithms. SOIL 8, 587–604 (2022).

Pham, B. T., Jaafari, A., Prakash, I. & Bui, D. T. A novel hybrid intelligent model of support vector machines and the multiboost ensemble for landslide susceptibility modeling. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 2865–2886 (2019).

Wadoux, A. M. J. C., Minasny, B. & McBratney, A. B. Machine learning for digital soil mapping: applications, challenges and suggested solutions. Earth Sci. Rev. 210, 103359 (2020).

Song, X. D. et al. Pedoclimatic zone-based three-dimensional soil organic carbon mapping in China. Geoderma 363, 114145 (2020).

Pham, K., Kim, D., Park, S. & Choi, H. Ensemble learning-based classification models for slope stability analysis. CATENA 196, 104886 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Schaap, M. G. & Wei, Z. Hierarchical Multimodel Ensemble Estimates of Soil Water Retention with Global Coverage. Geophysical Research Letters 47, e2020GL088819 (2020).

Caubet, M., Román Dobarco, M., Arrouays, D., Minasny, B. & Saby, N. P. A. Merging country, continental and global predictions of soil texture: lessons from ensemble modelling in France. Geoderma 337, 99–110 (2019).

Adeniyi, O. D., Brenning, A., Bernini, A., Brenna, S. & Maerker, M. Digital Mapping of Soil Properties Using Ensemble Machine Learning Approaches in an Agricultural Lowland Area of Lombardy, Italy. Land 12, 494 (2023).

Gong, Z., Zhang, X., Chen, J. & Zhang, G. Origin and development of soil science in ancient China. Geoderma 115, 3–13 (2003).

Shi, G. et al. A China dataset of soil properties for land surface modelling (version 2, CSDLv2). Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 17, 517–543 (2025).

Chen, J. Anthropogenic soils and soil quality change under intensive management in China. Geoderma 115, 1–2 (2003).

Wu, X., Wu, K., Zhao, H., Hao, S. & Zhou, Z. Impact of land cover changes on soil type mapping in plain areas: evidence from Tongzhou district of beijing, China. Land 12, 1696 (2023).

Heuvelink, G. B. M. et al. Machine learning in space and time for modelling soil organic carbon change. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 72, 1607–1623 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. Machine-Learning variables at different scales vs. Knowledge-based variables for mapping multiple soil properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 82, 645–656 (2018).

Ma, Y., Minasny, B., Demattê, J. A. M. & McBratney, A. B. Incorporating soil knowledge into machine-learning prediction of soil properties from soil spectra. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 74, e13438 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Evaluation of conditioned Latin hypercube sampling for soil mapping based on a machine learning method. Geoderma 369, 114337 (2020).

Suuster, E., Ritz, C., Roostalu, H., Kõlli, R. & Astover, A. Modelling soil organic carbon concentration of mineral soils in arable land using legacy soil data. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 63, 351–359 (2012).

Goldberg, D. E. & Holland, J. H. Genetic algorithms and machine learning. Mach. Learn. 3, 95–99 (1988).

Soleimani, H. & Kannan, G. A hybrid particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithm for closed-loop supply chain network design in large-scale networks. Appl. Math. Model. 39, 3990–4012 (2015).

Wu, X., Li, Y., Wu, K. & Hao, S. GA-Optimized sampling for soil type mapping in plain areas: integrating legacy maps and multisource covariates. Agronomy 15, 963 (2025).

Wadoux, A. M. J. C. & McBratney, A. B. Hypotheses, machine learning and soil mapping. Geoderma 383, 114725 (2021).

Arrouays, D. et al. Soil legacy data rescue via globalsoilmap and other international and National initiatives. GeoResJ 14, 1–19 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. Digital mapping of GlobalSoilMap soil properties at a broad scale: A review. Geoderma 409, 115567 (2022).

Mienye, I. D. & Sun, Y. A. Survey of ensemble learning: concepts, algorithms, applications, and prospects. IEEE Access. 10, 99129–99149 (2022).

Ganaie, M. A., Hu, M., Malik, A. K. & Tanveer, M. Suganthan, P. N. Ensemble deep learning: A review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 115, 105151 (2022).

Tsakiridis, N. L., Tziolas, N. V., Theocharis, J. B. & Zalidis, G. C. A genetic algorithm-based stacking algorithm for predicting soil organic matter from vis–NIR spectral data. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 70, 578–590 (2019).

Lieske, D. J., Schmid, M. S. & Mahoney, M. Ensembles of ensembles: combining the predictions from multiple machine learning methods. In Machine Learning for Ecology and Sustainable Natural Resource Management (eds Humphries, G. et al.) 109–121 (Springer International Publishing, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96978-7_5.

Wei, L. et al. An improved gradient boosting regression tree Estimation model for soil heavy metal (Arsenic) pollution monitoring using hyperspectral remote sensing. Appl. Sci. 9, 1943 (2019).

Stum, A. K., Boettinger, J. L., White, M. A. & Ramsey, R. D. Random forests applied as a soil Spatial predictive model in arid Utah. In Digital Soil Mapping: Bridging Research, Environmental Application, and Operation (eds Boettinger, J. L. et al.) 179–190 (Springer Netherlands, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8863-5_15.

Behrens, T. et al. Hyper-scale digital soil mapping and soil formation analysis. Geoderma 213, 578–588 (2014).

Kempen, B., Brus, D. J. & Heuvelink, G. B. M. Soil type mapping using the generalised linear Geostatistical model: A case study in a Dutch cultivated peatland. Geoderma 189–190, 540–553 (2012).

Chaney, N. W. et al. A 30-meter probabilistic soil series map of the contiguous united States. Geoderma 274. POLARIS, 54–67 (2016).

Abirami, G. et al. An integration of ensemble deep learning with hybrid optimization approaches for effective underwater object detection and classification model. Sci. Rep. 15, 10902 (2025).

Krumbein, W. C. Factors of soil formation: A system of quantitative Pedology. Hans Jenny. J. Geol. 50, 919–920 (1942).

Weil, R. & Brady, N. Nature and Properties of Soils, The. (2016).

Dickson, B. L. & Scott, K. M. Recognition of aeolian soils of the Blayney district, NSW: implications for mineral exploration. J. Geochem. Explor. 63, 237–251 (1998).

Bockheim, J. G., Gennadiyev, A. N., Hartemink, A. E. & Brevik, E. C. Soil-forming factors and soil taxonomy. Geoderma 226–227, 231–237 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Aeolian soils on the Eastern side of the Horqin sandy land, china: A provenance and sedimentary environment reconstruction perspective. CATENA 210, 105945 (2022).

Zhenghu, D., Honglang, X., Zhibao, D., Gang, W. & Drake, S. Morphological, physical and chemical properties of aeolian sandy soils in Northern China. J. Arid Environ. 68, 66–76 (2007).

Xu, W., Cai, Y. P., Yang, Z. F., Yin, X. A. & Tan, Q. Microbial nitrification, denitrification and respiration in the leached cinnamon soil of the upper basin of Miyun reservoir. Sci. Rep. 7, 42032 (2017).

Ouyang, N. et al. Clay mineral composition of upland soils and its implication for pedogenesis and soil taxonomy in subtropical China. Sci. Rep. 11, 9707 (2021).

Gerasimova, M. I. Chinese soil taxonomy: between the American and the international classification systems. Eurasian Soil. Sc. 43, 945–949 (2010).

Eswaran, H., Ahrens, R., Rice, T. J. & Stewart, B. A. Soil Classification: A Global Desk Reference (CRC, 2002).

Shi, X. Z. et al. Cross-Reference benchmarks for translating the genetic soil classification of China into the Chinese soil taxonomy. Pedosphere 16, 147–153 (2006).

Liu, Y., Wu, S., Zheng, D. & Dai, E. Soil indicators for eco-geographic regionalization: A case study in mid-temperate zone of Eastern China. J. Geogr. Sci. 19, 200–212 (2009).

Suo, L., Huang, M., Zhang, Y., Duan, L. & Shan, Y. Soil moisture dynamics and dominant controls at different Spatial scales over semiarid and semi-humid areas. J. Hydrol. 562, 635–647 (2018).

Shi, X. Z. et al. Soil database of 1:1,000,000 digital soil survey and reference system of the Chinese genetic soil classification system. Soil. Surv. Horizons. 45, 129–136 (2004).

Shi, X. et al. Reference benchmarks relating to great groups of genetic soil classification of China with soil taxonomy. Chin. Sci. Bull. 49, 1507–1511 (2004).

Mapa, R. B. Soil research and soil mapping history. In The Soils of Sri Lanka (ed. Mapa, R. B.) 1–11 (Springer International Publishing, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44144-9_1.

Shi, X. Z. et al. Cross-Reference system for translating between genetic soil classification of China and soil taxonomy. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2004.0318

Lagacherie, P. & Digital Soil Mapping, A state of the Art. In Digital Soil Mapping with Limited Data (eds Hartemink, A. E. & McBratney, A.) 3–14 (Springer Netherlands, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8592-5_1 (& Mendonça-Santos, M. de L.)

Huang, B., Yang, G., Lei, J. & Wang, X. A partitioned conditioned Latin hypercube sampling method considering Spatial heterogeneity in digital soil mapping. Sci. Rep. 15, 12851 (2025).

Mohammed, A. & Kora, R. A comprehensive review on ensemble deep learning: opportunities and challenges. J. King Saud Univ. - Comput. Inform. Sci. 35, 757–774 (2023).

Parvizi, Y. & Fatehi, S. Geospatial digital mapping of soil organic carbon using machine learning and Geostatistical methods in different land uses. Sci. Rep. 15, 4449 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the funding by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 42271261), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Agricultural Remote Sensing and Information Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. S.H. and J.Z. contributed to the experimental design, data collection, and analysis. E.Y. provided critical insights and helped with data interpretation. K.W. and Y.L. proposed the methodology and approach. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Wu, K., Hao, S. et al. Machine learning ensemble technique for exploring soil type evolution. Sci Rep 15, 24332 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10608-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10608-8