Abstract

Audit programs are essential for effective Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) implementation to monitor compliance, ensure adherence, and optimize outcomes. To address the lack of a tailored ERAS audit program in South Korea, we developed the Korean ERAS Research and Audit System (K-ERAS) in collaboration with anesthesiologists and surgeons. This system integrates data from a concurrently conducted prospective observational study on colorectal cancer surgery and features a real-time dashboard for perioperative outcome visualization and data completeness monitoring. Using records from 556 patients registered between October 2023 and October 2024, we assessed data completeness, dashboard feasibility, and ERAS compliance rates. Data entry for all patients was successfully completed, and the K-ERAS effectively captured and visualized perioperative data. The overall ERAS compliance rate was 47.4%, with notably low adherence to perioperative fasting (0.9% for both shortened preoperative fasting and carbohydrate loading, 2.5% for postoperative early water intake, and 29.0% for postoperative early oral feeding) and pain management protocols (2.7% for preemptive analgesia, 30.9% for regional analgesia, and 30.6% for routine use of two or more non-opioid analgesics postoperatively). The K-ERAS proved to be a reliable and adaptable system for managing perioperative data within an ERAS-focused framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) is a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, multimodal perioperative care bundle designed to improve surgical outcomes1. However, despite its well-established benefits, the integration of ERAS into routine clinical practice remains challenging2. Similarly, while the principles of ERAS are widely acknowledged in Korea, their practical implementation remains limited2.

Previous studies have shown that adherence to ERAS protocols can reduce postoperative complications or emergency room visit3,4,5. Among the various strategies to enhance adherence, audit and feedback, incorporating multimodal interventions, have been shown to be effective in improving compliance among healthcare providers6. Audit programs are considered a core component of ERAS, facilitating data collection, monitoring compliance, providing feedback, and enabling ongoing protocol optimization7. In contrast, the lack of a structured audit and feedback system can create a substantial barrier to the successful adoption and long-term sustainability of ERAS protocols8.

A representative example of an ERAS audit program is the ERAS® Interactive Audit System (EIAS), developed by the ERAS® Society and currently managed by the commercial company Encare (Stockholm, Sweden)9. A validation study conducted in 12 Swedish ERAS centers reported that the EIAS provided extensive coverage, high accuracy for major variables, and a low rate of missing data10. Another study on ERAS implementation utilizing the EIAS found that real-time auditing through the system enhanced compliance and helped maintain high-quality data11. Furthermore, a retrospective study using the EIAS database highlighted that the system was valuable not only for tracking compliance and delivering actionable feedback but also for assessing the overall impact of ERAS12.

However, no ERAS audit program has been tailored to the needs of the Korean healthcare system. To address this limitation, we developed the Korean ERAS Research and Audit System (K-ERAS) that utilizes ERAS-focused perioperative variables routinely collected in Korean clinical settings as part of a national research and development program dedicated to ERAS. By comparing each institution’s data with key indicators from other participating centers, such as length of hospital stay, postoperative complications, and patient-reported outcomes, K-ERAS is expected to provide real-time feedback on institutional performance, thereby supporting continuous quality improvement in perioperative care. As part of this effort, we established a prospective data registry for patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery across six tertiary hospitals while concurrently developing an audit program. We expect that K-ERAS will play a pivotal role in facilitating cost-effective implementation and broad adoption of ERAS protocols throughout South Korea in the future. This study aimed to introduce the development process and distinctive features of the K-ERAS and to investigate the current landscape of perioperative management in colorectal cancer surgery in South Korea based on data collected through the K-ERAS.

Method

Background and ethics of the development of K-ERAS

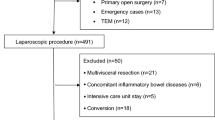

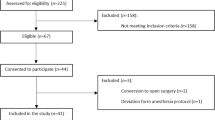

The development of this program began in June 2023 as part of a national research project led by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea. This project focuses on implementing ERAS in cancer surgery. Recognizing the importance of prospective database and audit program in sustaining ERAS, we initiated the development of K-ERAS, the first web-based ERAS registry tailored for the Korean clinician environment. The K-ERAS was designed for colorectal and gastric cancer surgeries with the participation of three anesthesiologists, three surgeons, one ERAS research nurse, and three program developers. Its development was carried out in parallel with a prospective observational study focusing on ERAS in patients undergoing minimally invasive colorectal cancer surgery (Project No.: RS-2023-CC140354). Patients from this study were registered in the K-ERAS, facilitating the identification and correction of errors and enhancement of program features to address any shortcomings. The initial version of the K-ERAS became available for use in mid-October 2023, and patient registration began at the end of October. The prospective patient registry involving six hospitals was conducted with approval from each hospital’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Seoul National University Hospital: H-2304-054-1421; Seoul National University Bundang Hospital: B-2310-858-402; Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center: 30-2023-57; Asan medical center: 2023-1037; National Cancer Center: NCC2023-0238; and Samsung medical center: SMC 2023-07-091), in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to registration in accordance with institutional guidelines and ethical standards. This study, which focused primarily on the program itself rather than human subject research, was granted an IRB waiver following consultation with the IRB of Seoul National University Hospital (No.: 2025-001).

K-ERAS was commissioned by the research team at Seoul National University Hospital and developed by a specialized medical data development company (Planit Healthcare, Seoul, South Korea) under a contractual agreement. The development process of the K-ERAS is outlined below (Fig. 1).

Selection of data entry items for the K-ERAS

Data entry items were classified into the following eight categories: Patient Information, Frailty, Nutrition, Surgery, Pathology, Anesthesia, Postoperative Outcomes, and EQ-5D-5L (Table 1). The selection of variables was performed by three anesthesiologists and three surgeons involved in the development. The frailty category focused on evaluating preoperative frailty using the Korean version of the FRAIL scale (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss of weight), which consisted of five questions13. The program was designed to automatically calculate the total score at the bottom of the screen as responses were entered. For the Nutrition category, which assesses the preoperative nutritional status, the NRS-2002 tool (body mass index, loss of weight, reduced dietary intake, and severe illness) was adopted for the nutrition category14. After the initial screening questions of the NRS-2002 were answered, the final screening section was automatically activated if any response was 'yes,' and the total score was calculated at the bottom of the screen as the responses were entered. The I-FEED score was used to evaluate postoperative gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction15. To enable quantitative evaluation of postoperative complications, each complication was categorized according to the Clavien-Dindo classification16. The system was further enhanced to automatically calculate the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI)17, which was conveniently displayed at the bottom of the interface. Additionally, to assess the quality of recovery, we selected the EuroQol five-dimensional descriptive system (EQ-5D-5L) from the recommended patient-reported outcome measures because of its brevity and ease of administration18.

Development of an ERAS status dashboard for healthcare provider feedback

In K-ERAS, the initial dashboard displayed upon selecting a specific protocol (gastric or colorectal cancer) was designed to present the overall institutional status. The dashboard includes the following metrics (Fig. 2): total number of registered patients; number of patient distribution by sex; number of admitted and discharged patients; age distribution in 10-year intervals; monthly average postoperative length of stay over the past 12 months; monthly overall ERAS compliance rates over the past 12 months; compliance rates for individual ERAS items, categorized by phase (Preadmission, Preoperative, Intraoperative, Postoperative); number of patients with common postoperative complications within 30 days; monthly rates of postoperative complications, classified as major (Clavien-Dindo classification IIIa or higher) or minor; distribution of CCI, displayed in 10-point intervals; EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), tracked from the day before surgery to postoperative day (POD) 5; pain intensity (at rest and during movement), recorded from the day before surgery to POD 5; and incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), tracked from the day before surgery to POD 5. The overall ERAS compliance rate was calculated as the percentage of completed items from a predefined ERAS checklist, whereas the compliance rates for individual items were visualized using radar charts segmented according to the perioperative phase. The ERAS checklist comprises protocol elements developed by six hospitals to facilitate the implementation of ERAS in minimally invasive colorectal cancer surgery. While it was informed by the ERAS® Society guidelines19, the checklist was adapted to the Korean clinical context through consensus among participating researchers. In some cases, the items were defined in greater detail than those in the original guidelines. For example, in the domain of pain management, the checklist includes the following specific elements: preemptive analgesia with oral or intravenous analgesics, intraoperative administration of non-opioid analgesics, intraoperative regional analgesia, and the routine postoperative use of at least two different types of non-opioid analgesics. Although 'no preoperative bowel preparation’ was not adopted in our ERAS protocol, it was included in the checklist to monitor its rate of implementation. Common postoperative complications were visualized using tree maps. For colorectal cancer, the dashboard provides an option to analyze the metrics for colon and rectal cancers separately. The dashboard offers an additional feature that allows users to view both the overall institutional status and detailed performance metrics specific to the researcher’s affiliated institution, ensuring a comprehensive yet institution-specific analysis.

Development of enhanced features to improve data entry efficiency

K-ERAS involves extensive data entry, and several efforts have been made to enhance both the accuracy and user-friendliness of this process. Users can input data directly into designated fields or select variables from a dropdown menu located beneath each field, thereby streamlining the entry process (Fig. 3A). A helper text feature was incorporated to provide concise explanations for each item when the cursor hovered the item’s name to assist users further (Fig. 3B). The system includes a comprehensive table that tracks the completion status of each patient to monitor and manage data entry efficiently. This table presents data completion status categorized by type (Step view, Fig. 4A) and surgical phase (‘Preop’, ‘Intraop’, ‘At Discharge’, ‘Pathology’, ‘POD30’) (Status view, Fig. 4B), with specific criteria defining completion for each phase. In the first table, the data entries are classified as complete, incomplete (partially entered data), or unsaved (no data entered). In the latter table, entries are categorized as complete, incomplete (partially entered data), or pending (the data entry timing is not yet due). The ‘Preop’ phase is marked as complete when data entry for the categories of Patient, Frailty, and Nutrition is finalized. The ‘Intraop’ phase is considered complete once the Surgery and Anesthesia categories are fully entered. For the ‘At Discharge’ phase, completion requires all variables in the postoperative outcome category to be entered, except for intensive care unit admission within 14 days, reoperation within 30 days, unplanned readmission within 30 days, 30-day postoperative mortality, and complications classified using the Clavien-Dindo system. The ‘POD30’ phase is marked as complete when these excluded variables are finalized. If data entry is not completed within 30 days postoperatively, the ‘POD30’ phase is classified as pending. However, once the 30-day period had passed, it was reclassified as incomplete. Finally, the ‘Pathology’ phase is deemed complete when all data within the Pathology category are entered.

This systematic approach enables users to quickly identify the data-entry status for each patient, highlighting any incomplete inputs and directing attention to areas requiring further work. By combining clear completion indicators, intuitive input options, and real-time progress tracking, the system aims to improve the efficiency and accuracy of data entry while reducing the user’s workload.

Bulletin board for facilitating researcher education and communication

Regular training is required to ensure accurate perioperative data entry and improve ERAS compliance. A bulletin board was integrated into the system to support this, enabling effective communication among researchers and facilitating education regarding ERAS protocols. This platform will serve as a centralized resource for sharing training materials specific to K-ERAS data entry and providing comprehensive educational content on ERAS. Moving forward, it can be used to enhance researcher training, promote knowledge sharing, and foster collaboration.

Statistical analysis

This study aimed to evaluate whether the data were accurately entered into the K-ERAS and whether the planned visualization of clinical indicators was implemented correctly. For this purpose, the following metrics were reported based on data collected through October 2024: average postoperative length of stay, overall and item-specific ERAS compliance rates, frequency of postoperative complications, trends in postoperative EQ-VAS scores, and incidence rates of postoperative pain and PONV. Descriptive statistics, including mean values, prevalence, and compliance rates, were calculated based only on the available data, without imputing missing values. As full-scale ERAS implementation began at the principal institution, Seoul National University Hospital, in November 2024, data collected only until October 2024 were included in the study. This allowed us to assess the baseline performance prior to the formal launch of the ERAS program.

No additional statistical analyses were performed because the focus was limited to reporting these status metrics. The K-ERAS dashboard was referenced for numerical values, and R software (version 4.3.1) was utilized for further explorations.

Results

Features of K-ERAS

The K-ERAS platform is hosted on Naver Cloud and uses a subaccount managed by Planit Healthcare. The development application server is configured with 1 vCPU, 1 GB RAM, 50 GB disk storage, and CentOS 7.8 (64-bit) as the operating system. The production application server, which was built by duplicating the image of the development server, features an upgraded specification of two vCPUs and 4 GB RAM. Both servers supported key services through Nginx (ports 80 and 443). For data management, the production database server was configured with one vCPU, 2 GB of RAM, 50 GB of disk storage, and PostgreSQL 9.4, providing both internal and external access to the designated ports. This comprehensive infrastructure supports efficient data collection, processing, and monitoring required for K-ERAS.

Data registered in K-ERAS as of October 2024

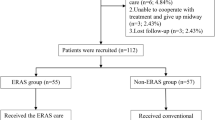

From October 2023 to October 2024, 556 patients who underwent elective colorectal cancer surgery (351 colon cancer and 205 rectal cancer surgeries) were registered in K-ERAS. The data entry for all patients was classified as complete. Of these, 315 (56.7%) were male, and those in their 60 s accounted for the largest proportion, 209 (37.6%) (Fig. 2).

Compliance with ERAS protocol of colorectal cancer surgery in K-ERAS

There was no substantial change in the overall implementation rate of the ERAS protocol, with an overall implementation rate of 47.4% (95% confidence interval, 46.5% to 48.2%) for all patients during the study period. The compliance rate showed a wide variability among the institutions, with the most compliant institution presenting a mean compliance rate of 58.0% ± 6.7% and the least compliant institution presenting 33.6% ± 6.2%.

The compliance rates for the individual ERAS elements during the period included in the K-ERAS are presented in Fig. 5 and Supplemental Table S1. Compliance rates for perioperative fasting-related measures were notably low. Compliance rates with shortened preoperative fasting, carbohydrate loading, early water intake, and early oral feeding were 0.9%, 0.9%, 2.5%, and 29.0%, respectively. Similarly, adherence to pain management strategies was suboptimal, with preemptive analgesia using non-opioid analgesics (2.7%), intraoperative regional analgesia (30.9%), and routine postoperative use of two or more non-opioid analgesics (30.6%).

The compliance rates for individual elements by institution are presented in Supplemental Table S2. Among the elements with overall low compliance, notable variation across institutions was observed.

Current perioperative management of colorectal cancer surgery in K-ERAS

The median postoperative length of stay was 7 days, with 6 days for colon cancer surgery and 7 days for rectal cancer surgery. Among the postoperative complications within 30 days, GI motility disorder was the most prevalent (46 cases, 8.3%), followed by bleeding, urinary complications, and anastomotic leakage (12 cases, 2.2%, respectively).

A summary of the subjective measures, including postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, and the quality of recovery, is presented in Fig. 6. The EQ-VAS score was the lowest on POD 1 (54.9 points and gradually increased thereafter but did not reach preoperative levels on POD 5 (71.1 vs preoperative 74.6) (Fig. 6A). Postoperative pain gradually decreased from the day of surgery. It was maintained as mild pain at rest (numerical rating scale [NRS] 3.7) from the postoperative day (POD) 1 and pain during movement (NRS 3.7) from POD 4 (Fig. 6B). Postoperative nausea and vomiting peaked at POD 1 (27.4% and 4.6%, respectively) and gradually decreased until POD 5 (4.6% and 0.8%, respectively) (Fig. 6C).

Discussion

This study outlined the development of K-ERAS, the first web-based ERAS registry specifically designed for auditing perioperative care in South Korea. We also evaluated the current state of perioperative management of patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery across six tertiary hospitals in South Korea. The K-ERAS was built with a robust infrastructure to support effective auditing and demonstrated stable data collection, including a total of 556 elective colorectal cancer surgery cases over 1 year. Evaluation of the data registered in K-ERAS provided valuable insights into the current perioperative practice of colorectal cancer surgery in South Korea, particularly revealing suboptimal adherence to the ERAS protocol in several aspects.

K-ERAS differs from EIAS in several respects. First, K-ERAS was specifically developed to support the implementation of ERAS protocols in Korea. Apart from the variable names, the platform was designed entirely in Korea to ensure its ease of use for Korean healthcare providers. Second, K-ERAS focuses primarily on cancer surgeries and, therefore, collects additional cancer-specific data not captured by the EIAS, such as pathology details, extent of lymph node dissection, resection margins, and methods for tumor localization. Third, the K-ERAS dashboard provides real-time data comparisons between individuals and registered institutions. This feature was designed to enable healthcare providers to benchmark their institution’s performance against aggregated trends across the registry, thereby facilitating timely feedback and evaluation. Fourth, the variables displayed on the K-ERAS dashboard differed from those on the EIAS. Specifically, the K-ERAS incorporates the CCI score to illustrate the distribution of postoperative complications and uses the EQ-VAS to illustrate trends in patients’ subjective perceptions of postoperative recovery. Patient-reported outcomes such as the EQ-5D-5L are widely recommended as measures for assessing the effectiveness of ERAS18. In addition, considering the importance of postoperative pain and PONV, the dashboard visualizes temporal changes using graphical representations. With these features, K-ERAS is expected to enhance the adoption and implementation of ERAS protocols in Korea, thus supporting more effective perioperative care.

The compliance rates for the ERAS items provided valuable insights into the perioperative management of colorectal cancer surgery in Korea, revealing several areas for improvement. Preadmission care lacks comprehensive patient education, anemia correction, prehabilitation for frail patients, and nutritional support for malnourished patients. Although the benefits of multimodal prehabilitation are well-documented20, their adoption in surgical patients remains limited in South Korea. This limitation is largely attributable to Korea’s fee-for-service reimbursement model, which does not provide designated coverage for preadmission care services. As a result, healthcare institutions in Korea face difficulties in allocating additional resources to support such interventions, contributing to their low implementation rates. To facilitate broader adoption of prehabilitation, it will be essential to demonstrate its cost-effectiveness within the Korean healthcare context and to establish appropriate reimbursement codes to support its integration into routine surgical care.

Unnecessarily prolonged perioperative fasting was identified as another key issue in this study. This finding is consistent with a recent survey conducted by the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition21, which reported that over 80% of respondents continued to follow the traditional midnight NPO practice. Moreover, solid food intake was most commonly initiated on POD 2. These findings indicate that perioperative fasting durations remain longer in Korea than in European countries22,23. In addition, despite the frequent use of bowel preparation, the recommended administration of oral antibiotics to reduce postoperative infections remains low24. Importantly, these gaps appear to result not from external barriers such as reimbursement constraints or limited resources, but rather from provider-related factors such as adherence to traditional routines, lack of motivation for change, and low outcome expectancy regarding evidence-based practices25. To overcome these challenges, it will be essential to implement structured educational programs targeting healthcare professionals and to generate local evidence demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of recommended ERAS components within the Korean healthcare context.

In addition, the implementation rates of multimodal analgesia components were also lower compared to those reported in European surveys22,23. In this study, preemptive analgesia with non-opioid analgesics, which is increasingly advocated for pain management26, has shown limited adoption. Similarly, regular use of two or more non-opioid analgesics and application of regional blocks were infrequently implemented. These findings are consistent with our recent survey in gastric cancer surgery which revealed similar trends27. These suboptimal implementation rates likely reflect a combination of provider-related factors and external barriers, including limited availability of trained personnel—particularly for regional block. To address these issues, multifaceted strategies will be required, including provider education and institutional efforts to support the routine use of multimodal analgesia.

Detailed analyses of postoperative pain and PONV in K-ERAS also revealed critical areas for improvement. On the day of surgery, movement-evoked pain reached severe levels, with an average score exceeding 7, whereas moderate pain (≥ 4) persisted through POD 3. Such pain during movement can hinder early ambulation and potentially delay postoperative recovery28,29. Furthermore, a substantial proportion of patients continue to experience PONV, which can disrupt early oral feeding. Impaired ambulation due to severe pain and delayed early oral intake caused by PONV are likely to be significant contributors to delayed GI recovery. Notably, GI motility disorders were the most common complications observed in our cohort. Targeted strategies to optimize pain control and PONV management are expected to play a pivotal role in reducing the incidence of GI motility disorders and ultimately enhancing postoperative outcomes.

Although this study confirmed that K-ERAS enables reliable data collection and real-time updates via its dashboard, several limitations require attention. First, broader institutional participation is required to ensure nationwide applicability. The multicenter registry revealed substantial variations in perioperative practices across hospitals. This diversity underscores the need for a comprehensive database that can capture the full range of perioperative practices, enabling standardized data collection and supporting continuous quality improvement efforts. Expanding participation will further enhance the representativeness of data and provide deeper insights into practical variability. Second, data analysis requires manual downloads and independent processing. Integrating basic analytical tools within the K-ERAS would facilitate real-time evaluation of ERAS outcomes in Korea. Third, given that each institution is manually entering information into the K-ERAS data items, a validation study based on actual electronic medical records may be necessary in the future. Fourth, although the research team developed the existing ERAS checklist, a broader consensus on the protocols is required for its widespread adoption. The recent Korean ERAS guidelines for colorectal surgery by the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition highlight unique recommendations such as endorsing preoperative mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics30, in contrast to the ERAS Society guidelines19. Incorporating Korea-specific ERAS protocols into the K-ERAS will support standardized perioperative care tailored to Korean clinical practice. In addition, our research group, in collaboration with ten Korean institutions, recently developed a Korea-specific ERAS protocol for gastric cancer surgery27. To facilitate its clinical adoption in Korea, we plan to initiate a multicenter study, and the protocol will be incorporated into the gastric cancer ERAS checklist within K-ERAS. Finally, our database is still in its early stages, and the current dataset does not include patients managed under the ERAS protocol. Our institution implemented the ERAS protocol in November 2024. To establish the utility of K-ERAS, it is important to visually present the impact of ERAS implementation on improving postoperative outcomes. Moreover, in the future, further research utilizing K-ERAS could be conducted to compare pre- and post-implementation of ERAS protocol.

It should also be noted that improving ERAS compliance requires more than the use of a prospective database for audit purposes; it requires a structured and systematic feedback process based on audit results31. Moreover, audit and feedback should not be a one-time effort, but rather a regular and continuous process to effectively enhance ERAS compliance, and ultimately improve surgical outcomes32. In this context, K-ERAS—which captures a comprehensive set of perioperative variables routinely collected in Korea—can serve as a valuable platform to support audit and feedback, thereby contributing to ongoing quality improvement in perioperative care nationwide.

In conclusion, the K-ERAS demonstrated reliability and adaptability, effectively managing a comprehensive array of perioperative variables through its ERAS-focused database. The data collected through K-ERAS provided valuable insights into the current perioperative management and adherence to ERAS protocols for colorectal cancer surgery in South Korea. This shows great promise in facilitating the development and implementation of standardized perioperative protocols across Korea. Nonetheless, continuous improvements are necessary to address its current limitations, optimize its functionality, and further enhance its impact on clinical practice.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ljungqvist, O., Scott, M. & Fearon, K. C. Enhanced recovery after surgery: A review. JAMA Surg. 152, 292–298 (2017).

Yoon, S. H. & Lee, H. J. Challenging issues of implementing enhanced recovery after surgery programs in South Korea. Anesth. Pain Med. (Seoul). 19, 24–34 (2014).

ERAS Compliance Group. The impact of enhanced recovery protocol compliance on elective colorectal cancer resection: Results from an international registry. Ann. Surg. 261, 1153–1159 (2015).

Ripollés-Melchor, J. et al. Association between use of enhanced recovery after surgery protocol and postoperative complications in colorectal surgery: the postoperative outcomes within enhanced recovery after surgery protocol (POWER) study. JAMA Surg. 154, 725–736 (2019).

Park, S. H. et al. Actual compliance rate of enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. J. Minim. Invasive Surg. 24, 184–190 (2021).

Ivers, N., et al. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6, CD000259 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3.

Fearon, K. C. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin. Nutr. 24, 466–477 (2005).

Meyenfeldt, E. M. V. et al. Implementing an enhanced recovery after thoracic surgery programme in the Netherlands: a qualitative study investigating facilitators and barriers for implementation. BMJ Open 12, e051513 (2022).

Currie, A. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery interactive audit system: 10 years’ experience with an international web-based clinical and research perioperative care database. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 32, 75–81 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Validity of routinely collected Swedish data in the international enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) DATABASE. World J. Surg. 45, 1622–1629 (2021).

Bisch, S. P. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in gynecologic oncology: System-wide implementation and audit leads to improved value and patient outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. 151, 117–123 (2018).

Pickens, R. C. et al. Impact of multidisciplinary audit of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)® programs at a single institution. World J. Surg. 45, 23–32 (2021).

Jung, H. W. et al. The Korean version of the FRAIL scale: Clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J. Intern. Med. 31, 594–600 (2016).

Kondrup, J., Rasmussen, H. H., Hamberg, O. & Stanga, Z., Ad Hoc ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): A new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 22, 321–336 (2003).

Alsharqawi, N. et al. Validity of the I-FEED score for postoperative gastrointestinal function in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Surg. Endosc. 34, 2219–2226 (2020).

Clavien, P. A. et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 250, 187–196 (2009).

Slankamenac, K., Graf, R., Barkun, J., Puhan, M. A. & Clavien, P. A. The comprehensive complication index: A novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann. Surg. 258, 1–7 (2013).

Abola, R. E. et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and perioperative quality initiative joint consensus statement on patient-reported outcomes in an enhanced recovery pathway. Anesth. Analg. 126, 1874–1882 (2018).

Gustafsson, U. O. et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations: 2018. World J. Surg. 43, 659–695 (2019).

Molenaar, C. J. L. et al. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation on reducing postoperative complications and enhancing functional capacity following colorectal cancer surgery: The PREHAB randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 158, 572–581 (2023).

Park, J. H. et al. Perioperative nutritional practice of surgeons in Korea: A survey study. Ann. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 16, 134–148 (2024).

Veziant, J. et al. Large-scale implementation of enhanced recovery programs after surgery. A francophone experience. J. Visc. Surg. 154, 159–166 (2017).

Gillissen, F. et al. Structured synchronous implementation of an enhanced recovery program in elective colonic surgery in 33 hospitals in The Netherlands. World J. Surg. 37, 1082–1093 (2013).

Koskenvuo, L. et al. Morbidity after mechanical bowel preparation and oral antibiotics prior to rectal resection: The MOBILE2 Randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 159, 606–614 (2024).

Cabana, M. D. et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 282, 1458–1465 (1999).

Xuan, C. et al. Efficacy of preemptive analgesia treatments for the management of postoperative pain: A network meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 129, 946–958 (2022).

Lee, H. J., et al. Survey of perioperative practices in gastric cancer surgery for establishing an enhanced recovery after surgery program across 10 tertiary hospitals in South Korea. J. Gastric Cancer. 25, e27.

Rivas, E. et al. Pain and opioid consumption and mobilization after surgery: Post hoc analysis of two randomized trials. Anesthesiology 136, 115–126 (2022).

Osland, E., Yunus, R. M., Khan, S. & Memon, M. A. Early versus traditional postoperative feeding in patients undergoing resectional gastrointestinal surgery: a meta-analysis. JPEN J. Parenter Enteral Nutr. 35, 473–487 (2011).

Lee, K. et al. The 2024 Korean enhanced recovery after surgery guidelines for colorectal cancer. Ann. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 16, 22–42 (2024).

McLeod, R. S. et al. Development of an enhanced recovery after surgery guideline and implementation strategy based on the knowledge-to-action cycle. Ann. Surg. 262, 1016–1025 (2015).

Pędziwiatr, M. et al. Early implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) protocol—Compliance improves outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 21, 75–81 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the developers of Planit Healthcare for their invaluable contributions to the development of the K-ERAS program.

Funding

This study was supported by the National R&D Program for Cancer Control through the National Cancer Center funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. RS-2023-CC140356, RS-2023-CC140357).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S-HY contributed to data curation, manuscript preparation, and manuscript revision. J-WJ, JK, MJK, JWP, DJP, and SYJ contributed to data curation. HJL contributed to study design, manuscript preparation, and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, SH., Ju, JW., Lee, HJ. et al. Development of the Korean enhanced recovery after surgery audit program. Sci Rep 15, 27409 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10622-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10622-w