Abstract

On March 28, 2025, a devastating earthquake doublet of moment magnitude 7.7 and 6.7 struck the Sagaing Region of Myanmar, causing extensive damage and significant casualties across Southeast Asia. In the months preceding this seismic event, a continuous radon monitoring system—BhaROSA—installed in Imphal, India, as a part of the Indian Network for Detecting Radon Anomaly signal (INDRA), recorded a pronounced and statistically significant novel radon anomaly signal. The anomaly signal commenced on December 5, 2024, with a gradual buildup, followed by a sharp rise on February 28, 2025. Multiple peak alerts were observed prior to the mainshock (7.7 Mw) on March 28, 2025, after which the signal declined rapidly, returning to baseline levels—suggesting a potential correlation with pre-seismic crustal stress accumulation and release. The anomaly signal exhibited a normalized squared deviation of 35.14 from the baseline value, far exceeding natural variability at the time of main shock. The radon signal, with a build-up period of approximately 109 days and a decay of ~ 96 h, closely matched the spatial and temporal characteristics of the dilatancy-diffusion model. A pooled analysis of radon anomalies from ten earthquake events, including this major event, across multiple Indian observatories of INDRA reveals a robust positive correlation (r = 0.96, R2 = 0.93) between radon buildup duration and earthquake magnitude. These findings strongly suggest that radon emissions are sensitive indicators of impending seismic activity and radon build up period can be a good indicator of magnitude of earthquake. The study highlights the potential of continuous radon monitoring in tectonically active regions like Northeast India and Myanmar as a viable component of earthquake precursor research and early warning systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

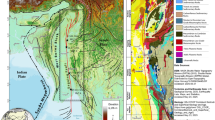

On March 28, 2025, at 06:20:52 UTC, a powerful earthquake with a moment magnitude 7.7 struck the Sagaing Region of central Myanmar (https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us7000pn9s/executive). The epicenter was located near Sagaing Township, approximately 14 km north-northwest of Sagaing city and just 16 km west of Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city. The earthquake occurred along the highly active Sagaing Fault, a major tectonic boundary between the Burma and Sunda plates, and was recorded at a shallow depth of approximately 10 km. Its shallow hypocenter and strike-slip faulting mechanism contributed to widespread, catastrophic damage across central Myanmar and extended to neighbouring countries, including Thailand, China, and Vietnam. The intensity shaking map of main event (7.7Mw) is shown in Fig. 1.

Macro-seismic Intensity Map of Myanmar earthquake 7.7 Mw that occurred on March 28, 2025, at 06:20:52 UTC (Big Data Viz (Ver 0.1) Interface, Ellyptech, India, URL: www.ellyptech.com/init/products/bigdataviz).

This earthquake marked the most significant seismic event in Myanmar since the 1912 Maymyo earthquake1 and stands as the second deadliest in the country’s modern history, surpassed only by the 1930 Bago earthquake2. The mainshock reached a maximum Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) of X (Extreme), as recorded in areas near the rupture zone, including Mandalay and parts of the Sagaing Region. The ground shaking was strong enough to be felt across much of Southeast Asia, including as far as Bangkok, Thailand—over 1,000 km from the epicenter—where geological conditions amplified long-period seismic waves, resulting in notable structural damage and casualties. The earthquake claimed the lives of over 3000 people in Myanmar3. In addition, over 7,800 people were injured, and hundreds more were reported missing.

The rupture extended along an estimated 460–500 km section of the Sagaing Fault, which runs from the Andaman Sea through Myanmar to the Himalayan collision zone (https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us7000pn9s/executive). Satellite data and seismic modeling indicate the event was a “supershear” earthquake, in which the rupture front moved faster than the shear wave speed, producing unusually intense ground motion. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reported a maximum slip of over 4 m near Sagaing, with the strongest seismic moment release occurring around 30 s into the event. Other agencies, including Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, suggest that the rupture involved three segments and a cumulative moment magnitude of up to 7.8, with maximum slip possibly exceeding 7 m.

Following the mainshock, the region experienced over 468 aftershocks within two weeks, including a strong 6.7 Mw event just 12 min after the initial quake (http://seismo.gov.in/MIS/riseq/earthquake). These aftershocks were distributed along a 400 km stretch of the fault, although a notable gap in seismic activity was observed in the central portion, possibly due to limited seismic instrumentation or rupture dynamics.

The tectonic setting of Myanmar places it at a nexus of active geological processes involving the Indian, Eurasian, Sunda, and Burma plates. The Sagaing Fault, a 1,400-km transform boundary, is among the most seismically hazardous in Southeast Asia. Historical records indicate that it has produced numerous destructive earthquakes in the twentieth century, including events in 1930, 1946, 1956, and 20124. However, paleoseismic studies suggest long recurrence intervals—100 to 150 years—for some fault segments, creating dangerous seismic gaps that may rupture with little to no warning5.In this instance, the earthquake ruptured the Pyu, Naypyidaw, Meiktila, and southern Sagaing fault segments, effectively closing a long-anticipated seismic gap identified in past studies. This rupture pattern overlaps zones affected by the 1929, 1930, and 1956 earthquakes4, highlighting the interconnected and cumulative stress buildup along the fault system.

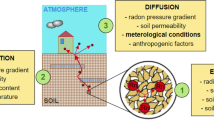

An earthquake precursor is a suitable parameter that results in an anomalous phenomenon which can be attributed to an impending earthquake with a good degree of confidence. There is a gamut of possible earthquake precursors cited in scientific literature, ranging from aeronomy to zoology which includes (i) Dilatancy–diffusion6, (ii) changes in ratio of primary and secondary seismic velocity (Vp/Vs)7, (iii) radon emission8,9, (iv)electromagnetic anomalies10, (v) animal behaviour11, (vi) satellite observation of the expected ground temperature declination12.

The mechanism by which radon acts as an earthquake precursor is commonly explained by the stress-dilatancy model13,14. This model posits that increasing tectonic stress within the Earth’s crust—prior to fault rupture—leads to microfracturing, dilatation, and pore pressure diffusion. These processes enhance radon gas release from soil, resulting in detectable anomalies in radon concentrations.

In our recent work15, we presented a pore pressure diffusion model and highlighted the utility of radon concentration gradients at the soil–air interface to enhance the sensitivity of detecting stress-induced radon signals. By applying pressure diffusion theory, we demonstrated how seismic stress accumulation in bedrock alters radon profiles in the sub-soil, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms driving stress-related radon variations.

Building upon this theoretical framework, we developed a remote-sensing, solar-powered radon monitoring system—Bhabha Radon Observatory for Seismic Application (BhaROSA) as shown in Fig. 2—which has been deployed at 100 locations under the Indian Network for Detecting Radon Anomaly signals (INDRA). This initiative aims to build a comprehensive database of radon anomalies associated with seismic activity, thereby enhancing our understanding of earthquake precursors and the potential for using radon as a geochemical tracer for earthquake prediction.

In the months leading up to the devastating earthquake doublet—with moment magnitudes of 7.7 and 6.7—that struck the Sagaing Region of Myanmar, the BhaROSA station operating in Imphal, India, recorded a pronounced and statistically significant radon anomaly. Notably, this station—located approximately 381 km from the earthquake epicenter—is the closest in the monitoring network.

The Radon Observatory located in Imphal, Manipur, India (Latitude: 24.751°N, Longitude: 93.929°E, Altitude: 779 m), was established on June 7, 2024, in one of India’s most tectonically volatile zones—Seismic Zone V16,17. Geologically, the Imphal region is part of the Indo-Burmese Arc (IBA), a prominent tectonic feature formed due to the oblique convergence between the Indian Plate and the Burmese Microplate. This arc is a folded and faulted belt composed primarily of Tertiary sedimentary sequences, including thick, loosely consolidated layers of shale, sandstone, siltstone, and clay. These porous and fractured lithologies are particularly conducive to radon migration, making the area an ideal site for geochemical monitoring as demonstrated in previous studies18,19. The stratigraphy of the region favors the accumulation and episodic release of radon due to the high uranium content in shale formations and the permeability of faulted sandstones.

The region is further characterized by a network of active thrust and strike-slip faults, such as the Churachandpur-Mao Fault (CMF) and the Sagaing Fault, which accommodate significant crustal deformation and seismic energy release. The frequent tectonic adjustments along these fault lines facilitate microfracturing and ground stress accumulation—processes that enhance radon emanation from the subsurface. Additionally, the crustal deformation in the IBA region is influenced by transpressional tectonics, resulting in both vertical and horizontal stress regimes that trigger radon anomalies prior to seismic events.

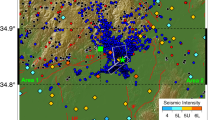

The observatory recorded a distinct, long-duration radon anomaly that commenced on December 5, 2024, and persisted until the major earthquake event on March 28, 2025. Within this anomalous period, three significant seismic events (Mw > 5.0) occurred within a 500 km radius of the monitoring station, as illustrated in Fig. 3. These included a local earthquake of magnitude 5.7 Mw on March 5, 2025, at an epicentral distance (ED) of 42.6 km, and a major earthquake doublet on March 28, 2025, comprising magnitudes of 7.7 Mw and 6.7 Mw, with epicentral distances of 381.5 km and 400.6 km, respectively.

Location of Radon Observatory and 3 earthquake events that occurred in the vicinity of the observatory during radon anomaly period (Big Data Viz (Ver 0.1) Interface, Ellyptech, India, URL: www.ellyptech.com/init/products/bigdataviz).

Our observations indicate that the 7.7 Mw Myanmar earthquake was preceded by a pronounced radon anomaly, sustained for over 100 days, and detected at a location more than 380 km from the epicenter. The temporal coincidence, directional consistency, and statistical robustness of the anomaly strongly support the hypothesis that radon serves as a physically meaningful precursor to large seismic events. These findings are consistent with dilatancy-diffusion models, which posit that microfracturing and associated changes in pore pressure under crustal stress promote enhanced radon emanation and migration to the surface.

Additionally, analysis of our aggregated dataset reveals a significant quantitative relationship between the duration of radon buildup and the magnitude of subsequent earthquakes, demonstrating the predictive potential of such geochemical signals. These results highlight the importance of establishing systematic radon monitoring networks in tectonically active regions. When integrated with geodetic, hydrological, and seismic datasets, continuous radon monitoring could provide a critical component of multi-parameter early warning systems, thereby contributing to the mitigation of earthquake-related risks.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics of radon and meteorological parameters at radon observatory

Figure 4 displays the time series data of four key environmental parameters—radon concentration (recorded at 15-min intervals), temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and atmospheric pressure (mbar)—monitored continuously at Imphal from June 7, 2024, to April 11, 2025. This dataset provides a comprehensive view of the temporal fluctuations in both geogenic and atmospheric conditions over an extended period. Figure 5 presents violin box plots for each parameter, offering a visual summary of their distribution patterns, including spread, skewness, and outliers. Complementing this, Table 1 provides descriptive statistics, capturing measures of central tendency (mean, median), variability (standard deviation, range), and distribution shape (kurtosis, skewness). Together, these representations are vital for interpreting local atmospheric behavior and assessing potential precursors linked to geophysical anomalies such as earthquakes20,21,22,23.

Radon counts, a key parameter for geophysical and seismic monitoring, displayed significant variability with a mean of 647 and a high standard deviation of 572, indicating frequent and substantial fluctuations. The skewness value of 2.96 suggests a positively skewed distribution, meaning higher values were more prevalent and the distribution is heavily tailed to the right. The kurtosis value of 12.67 indicates a highly peaked distribution with heavy tails, further highlighting the presence of extreme radon concentration events. The maximum count recorded was 5269, while the minimum was 94, with a median of 512, suggesting that a majority of readings were lower than the mean due to a few extreme high values.

Temperature data showed a mean of 27.2 °C and a standard deviation of 12.1, reflecting a moderate level of variation over the observation period. The slight negative skewness (-0.35) indicates a tendency toward cooler temperature events, with more frequent occurrences of lower-than-average temperatures. The kurtosis value of − 1.16 suggests a flatter distribution compared to a normal curve, indicating fewer extreme temperature events. The median temperature was 34.5 °C, with a range spanning from 24.1 °C to 42.2 °C, showing a relatively wide spread in seasonal or daily temperature variations.

Relative humidity showed a mean of 36.1% and a standard deviation of 15.5%, pointing to significant variability, likely influenced by seasonal monsoon effects. The skewness of 0.27 suggests a slightly right-skewed distribution, while the kurtosis value of 1.96 indicates a distribution close to normal but with slightly heavier tails. The minimum recorded relative humidity was 32.8%, the median was 41.8%, and the maximum was 60.8%, indicating a fairly balanced distribution around the central values with occasional spikes in moisture levels.

Atmospheric pressure exhibited the least variability among all the measured parameters, with a mean of 923.8 mbar and a standard deviation of 4.1. The distribution was slightly negatively skewed (-0.19), implying a mild tendency toward lower pressure readings, while the kurtosis of − 0.62 points to a slightly platykurtic distribution, indicating fewer extreme pressure values. The minimum recorded pressure was 909.8 mbar, the maximum was 934.6 mbar, and the median closely matched the mean at 923.7 mbar, suggesting a stable atmospheric pressure pattern over the study period.

Diurnal and noise filtering of radon signal

Figure 6 presents a three-panel time series of radon concentration from December 2024 to April 2025, demonstrating the separation of diurnal variation and the application of noise filtering techniques for long-term anomaly detection. The bottom panel shows the raw radon data, which reveals a gradual increase beginning in mid-December, transitioning into a prominent and sustained build-up phase from late February 2025. This culminates in a sharp peak in early March, followed by a rapid decline in early April. Superimposed on this trend are regular oscillations corresponding to the natural diurnal variation of radon. The middle panel isolates this diurnal component, extracted using a 4th-order Butterworth band-pass filter24, and displays a stable daily pattern that persists even during the anomaly period. Notably, the amplitude of diurnal oscillations increases during the anomaly peak, suggesting that the daily cycle was not disrupted but instead amplified—likely due to enhanced subsurface radon accumulation, which increases the concentration gradient between soil and atmosphere. The top panel presents the filtered radon signal, with the diurnal and high-frequency noise components removed to expose the underlying long-term trend. This processed data clearly shows a smooth and sustained radon build-up beginning in early-December, peaking in early March, and decaying rapidly thereafter. The presence of a persistent anomaly in the filtered data—distinct from diurnal patterns—indicates a potential geophysical origin, plausibly linked to subsurface stress accumulation or seismic processes. The preservation of a consistent diurnal pattern and the absence of erratic fluctuations further support the conclusion that the anomaly is not due to spurious noise or meteorological influences, but may serve as a precursor signal to seismic activity.

Time series plot of radon data at Imphal Observatory showing (from bottom to top): raw radon counts, the extracted diurnal component, and the residual radon signal after removal of diurnal and high-frequency noise. This decomposition highlights the underlying long-term anomaly trend, distinct from natural diurnal variations, and facilitates clearer identification of geophysically significant deviations.

Radon anomaly versus meteorological parameter variation

Figure 7 presents a comparative time series of normalized deviations—expressed as absolute deviation divided by standard deviation—for radon (black), atmospheric pressure (red), relative humidity (green), and temperature (blue) spanning December 2024 to April 2025. The primary objective of this comparison is to evaluate the behavior of the radon signal relative to potential meteorological confounders. The radon data show a clear and sustained deviation beginning in early December, sharply intensifying in late February, and peaking in early March 2025, with values surpassing 80 standard deviations (σ) above the baseline. This signal significantly exceeds the ± 2σ threshold (indicated by dashed lines), commonly used to identify statistically significant anomalies.

Time series plot showing the relative changes in radon, temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure during the radon anomaly progression at Imphal Observatory. While radon exhibits a significant and sustained deviation, no corresponding anomalies are observed in the meteorological parameters. The stability of temperature, humidity, and pressure throughout the period effectively rules out meteorological influences as the cause of the observed radon anomaly.

In contrast, all meteorological parameters—pressure, humidity, and temperature—remain well within the ± 2σ range throughout the observation period, exhibiting only modest, short-term fluctuations. The lack of corresponding anomalies in these environmental variables indicates that the observed radon excursion is unlikely to be the result of atmospheric influences such as barometric pumping, soil moisture variation, or temperature-induced diffusion. These findings strongly support the interpretation that the radon anomaly is of geophysical origin, likely driven by subsurface processes such as stress accumulation and enhanced gas migration preceding seismic activity. The marked divergence between the radon response and meteorological stability reinforces the potential of radon as a reliable and independent precursor to earthquakes.

Radon anomaly versus Myanmar earthquake

Figure 8 shows the time series plot of radon counts, its daily and monthly moving average and seismic events having strain radius greater than epicentral distance. The daily moving average (blue line) showed a steady climb from November 2024, crossing the Median + 2σ threshold (grey dashed line) in early December 2024—a common statistical benchmark for anomaly detection. The monthly moving average (green line) confirmed a persistent trend well above the normal baseline, culminating in a sharp and distinct spike in mid to late March. Following this peak, radon levels declined abruptly in the aftermath of the March 28 earthquake, consistent with stress relaxation in the crust.

Notably, three seismic events were observed during this period. A 5.7 Mw earthquake, located just 42.6 km from the station, occurred during the early phase of the radon rise and 1st peak and may have contributed to localized stress changes. The main 7.7 Mw earthquake on March 28—temporally and spatially aligned with the radon peak—is likely the primary seismic event associated with the observed anomaly. A subsequent 6.7 Mw event, occurring shortly after and at a similar distance (~ 400.6 km), may reflect continued regional tectonic adjustments.

As shown in Fig. 8, the anomaly signal commenced on December 5, 2024, with a gradual buildup, followed by a sharp rise on February 28, 2025. Multiple peak alerts were observed prior to the mainshock (Mw 7.7) on March 28, 2025, after which the signal declined rapidly, returning to baseline levels—suggesting a potential correlation with pre-seismic crustal stress accumulation and release. Th anomaly evolved gradually, spanning a signal build up time of approximately 2618 h (~ 109 days), indicative of a sustained build-up of stress in the Earth’s crust. The signal decayed rapidly over a period of ~ 96.5 h (~ 4 days), reflecting a possible release of crustal stress following the occurance of three seismic events. Statistical measures reinforce the significance of this anomaly: a normalized squared deviation of 35.14 from base line value at the time of earthquake and a maximum radon amplification of 3.64 times above background levels suggest that the observed variation was not due to random fluctuations but a physically driven process. The main earthquake occurred at a depth of 35 km, with an epicentral distance of 381.45 km from the monitoring station. The four-day gap between the radon peak alert and the seismic event is consistent with findings from earlier study15,18, which show that radon anomalies often precede major earthquakes by days to weeks. Additionally, the azimuthal direction of 144.7° and an SR/ED (Stress Radius to Epicentral Distance) ratio of 4.40 support the geophysical plausibility of stress transmission from the earthquake source to the monitoring site. The strain radius of earthquake is defined by Dobrovolsky25 as follows:

where M is the moment magnitude of the earthquake.

The strong spatial and temporal linkage between the radon anomaly and the Myanmar earthquake supports the hypothesis that pre-seismic radon emissions are viable indicators of impending seismic events. The slow accumulation and rapid decay pattern, high anomaly magnitude, and alignment with a major earthquake collectively underscore the potential of radon monitoring as a tool for earthquake precursor studies in tectonically active regions like Northeast India and adjoining Myanmar.

A dilatancy-based perspective of radon anomaly

The anomalous radon variations observed at Imphal in the days leading up to the destructive 7.7 Mw Myanmar earthquake can be comprehensively interpreted through the lens of dilatancy theory13. According to this hypothesis, rocks under increasing tectonic stress undergo inelastic volumetric expansion prior to failure—a phenomenon termed dilatancy (illustrated in Fig. 9).

Previous studies26 have attempted to model this mechanism through 1-D radon diffusion and advection in porous media. However, such models often assume radon emanation from depths as great as 10 km. Given radon’s short half-life (3.82 days), these models predict transit times of decades for radon to travel from the hypocenter to the surface—an estimate inconsistent with the rapid precursor signals typically observed days to months before seismic events8.

To reconcile this discrepancy, recent models15 propose that it is not the radon itself that travels from the hypocenter, but rather the pore pressure front that rapidly propagates through the crust. This pressure perturbation, arising from crustal compression and elastic-inelastic deformation cycles, mobilizes existing radon already present in the upper crust or soil layers, thereby modifying the sub-soil radon concentration profile and increasing the exhalation rate at the surface.

At Imphal, geographically proximal to the epicenter and situated within a tectonically sensitive region of Indo-Myanmar arc, the observed radon anomaly aligns well with this theory. A significant spike in radon concentration was detected days to weeks prior to the seismic event. This timing matches the typical 10–100 day window between rock dilatancy and earthquake rupture proposed in the original dilatancy framework13.

Furthermore, the fast transient behavior of the radon signal prior to the Myanmar earthquake supports a mechanism dominated by pore pressure diffusion, rather than slow-moving advection. Unlike fluid transport, which proceeds at typical velocities of ~ 10 μm/s27, pore pressure diffusion travels orders of magnitude faster, enabling radon anomalies to manifest at the surface within days following subsurface stress changes.

The radon anomaly observed at Imphal before the 7.7 Mw Myanmar earthquake provides compelling evidence for the dilatancy-diffusion hypothesis, wherein crustal compression induces rapid pore pressure diffusion, triggering surface-level radon exhalation. This mechanism offers a plausible explanation for the timely and measurable radon fluctuations seen prior to seismic rupture and highlights the potential of radon monitoring as a viable tool in short-term earthquake forecasting.

Pooled analysis of previously recorded radon precursory signals and their correlated earthquake events

It is insightful to compare the radon anomaly signal observed during the present study with previously recorded radon anomalies that preceded specific earthquake events at multiple observatories. Only those events were considered where the epicentral distance fell within the strain radius of the respective earthquake, as defined by Eq. (1), ensuring a physically meaningful connection between the radon signal and the seismic source.

Table 2 presents a comparative summary of radon anomaly characteristics recorded prior to ten distinct earthquake events across various radon monitoring stations in India. Only anomalies with a minimum buildup period of 100 h have been considered, as such long-duration anomalies are more likely to be seismically induced, whereas meteorological radon anomalies are typically short-lived. The dataset captures key temporal markers such as the start, peak, and end times of the anomalies, along with amplitude factors, buildup and decay periods, and details of the corresponding seismic events. This comprehensive information helps in understanding how radon emission patterns vary with earthquake magnitude, distance from the epicenter, and local geological conditions.

Figure 10 reveals a strong positive correlation between the radon anomaly buildup duration (in hours) and the magnitude (Mw) of the ensuing earthquake. The linear regression trend line (shown in red) clearly indicates that longer buildup periods are associated with stronger earthquakes. The correlation is statistically significant, with a Pearson’s coefficient of r = 0.96 and a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.93, indicating that over 93% of the variation in earthquake magnitude can be explained by the radon buildup duration alone.

Furthermore, the bubble sizes in the graph represent epicentral distances (ED), providing spatial insight into detection range. Larger bubbles—indicating greater distances—are typically associated with higher magnitude events and longer buildup periods, suggesting that significant earthquakes can generate detectable radon signals even at considerable distances. In contrast, smaller events (4.0–4.5 Mw ) show shorter buildup periods and tend to be recorded closer to the epicenter. These findings highlight the potential of radon monitoring networks not only for magnitude estimation but also for contributing to early warning systems and regional seismic hazard assessments. A detailed analysis of these events, however, lies beyond the scope of the current manuscript.

Preliminary assessment of true–false positives and detected-missed events

Figure 11 presents a preliminary assessment of radon anomaly detection performance from December 14, 2023, to July 14, 2024, using data collected from multiple observatories within the INDRA network. This timeframe was selected due to the stable and optimal operation of most stations. The evaluation methodology for identifying True–False Positives and Detected-Missed Events is detailed in the Methods section. The analysis considers earthquakes of magnitude M > 3, occurring within 100 h of a detected radon anomaly and within the strain radius of the event’s epicenter. The time period of 100 h is selected based on the finding that seismic events typically occur within 3 to 4 days following the initiation of the dilatancy phase13,15. The results reveal a true positive rate of 72%, a false positive rate of 28%, and a detection success rate of 82%, with 18% of seismic events missed—often due to limited station density in the affected areas.

The metric of true and false positive along with detected and missed seismic events. An anomaly is classified as a True Positive if an earthquake occurs within 100 h and has an epicentral distance less than the strain radius of the earthquake; otherwise, it is classified as a False Positive. A detected event is an earthquake that occurs with at least one prior radon anomaly within 100 h from an observatory located within the strain radius, whereas a missed event is an earthquake that occurs without any prior radon anomalies.

It is important to note that this study is observational and retrospective. Future multi-station monitoring and prospective analysis are recommended for more definitive validation of the predictive power of radon anomalies in seismic forecasting. However, improving detection reliability and minimizing false positives remain essential. In this context, machine learning (ML) techniques offer significant promise. ML algorithms can be trained on large, multi-parameter datasets to capture complex, nonlinear relationships that conventional statistical methods may overlook. Supervised learning approaches can assist in classifying anomaly types, while unsupervised learning can help distinguish between natural variability and true geophysical signals.

Future work will prioritize the integration of ML-based anomaly detection28, improved temporal and spatial correlation across multiple stations in varied tectonic environments29, and detailed quantification of radon anomaly features such as buildup rates, decay profiles, and amplitude shifts. These enhancements are expected to reduce false positives, identify weak or emergent seismic precursors more effectively, and support real-time early warning systems. In addition, expanding station coverage in tectonically active regions and incorporating meteorological, geological, and geodetic parameters into ML models will further strengthen predictive performance.

Beyond radon data alone, a multiparametric approach—including inputs such as GPS measurements, InSAR data, and seismic strain rates—will be essential for validating the seismic origin of radon anomalies. Such an integrated framework will increase scientific confidence in radon-based earthquake forecasting and support its operational implementation.

Methods

Bhabha radon observatory for seismic application (BhaROSA)

The architecture of the BhaROSA system is schematically illustrated in Fig. 2. The design follows the accumulator theory for monitoring radon exhalation from the ground30. According to this principle, an accumulator with a shorter height and wider base reaches radon steady-state concentrations more quickly. Based on this, a cylindrical accumulator with a radius of 10 cm and height of 10 cm was selected, providing a system response time of less than one hour.

To isolate the radon signal from environmental noise, a cylindrical diffusion barrier (2 feet in diameter, 3 feet in depth) was embedded approximately 1 m into the soil. This barrier was backfilled with dry, native soil up to ground level to simulate natural conditions. The accumulator chamber was positioned at the center of this barrier at the soil-air interface, with its base edge embedded approximately 5 cm into the soil. To further minimize environmental influences such as rainfall and temperature variations, the surrounding 1-m radius was sheltered using an insulated canopy.

The radon probe is a compact, automated sensor specifically designed for continuous, real-time monitoring of radon exhalation. It operates on the accumulation chamber method, wherein radon diffusing from the soil surface is temporarily confined within a sealed chamber. The accumulated radon is then quantified using a ZnS:Ag scintillation cell-based radon counter15.

As shown in Fig. 2, BhaROSA integrates a Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) gateway to facilitate communication between multiple sensors via a wired network. MQTT is a lightweight, publish-subscribe protocol optimized for machine-to-machine (M2M) and Internet of Things (IoT) applications, offering low overhead and robustness under constrained network conditions.

Sensor data is first published to a local MQTT server hosted on the gateway and then transmitted via a secure internet connection to a central monitoring station. Each sensor transmits data under topic-specific headers, including timestamps and station identifiers. Additionally, system health parameters—such as battery level, solar panel status, and sensor diagnostics—are published on separate channels.

Sensor data is uploaded at 15-min intervals. In case of network outages, the system supports data buffering and retrieval, allowing the central station to query remote nodes for any missing data. All incoming data are logged into a MySQL database at the central station for long-term storage, analysis, and visualization.

Anomaly detection in radon and meteorological parameters

Radon decay and its associated counting statistics follow a Poisson distribution. Accordingly, anomalies in the radon signal are detected using a Poisson-based 2σ threshold, where the Poisson Sigma (σ) is estimated as the square root of the measured radon counts. Under stable, undisturbed conditions—i.e., in the absence of external geophysical influences—approximately 95% of the data are expected to lie within the median ± 2σ range. Any radon measurement, after removal of diurnal cycle (24 h moving average), that falls outside this confidence interval is considered statistically significant and is flagged as a radon anomaly. The median is used instead of the mean to represent the baseline, as it is less sensitive to outliers and provides a more robust measure of central tendency in the presence of anomalous value.

For each identified radon anomaly, the following temporal markers are defined:

-

Anomaly Start Time: The first instance when the radon concentration exceeds the 2σ threshold.

-

Anomaly Peak Time: The point at which the radon signal reaches its local maximum.

-

Anomaly End Time: The time when the radon concentration returns to within the median ± 2σ range.

Meteorological anomalies are identified using a similar statistical approach. For atmospheric parameters such as temperature, relative humidity, and pressure, anomalies are defined as deviations that exceed ± 2 standard deviations (σ) from the median baseline. This threshold is based on the assumption that, under normal (Gaussian or near-Gaussian) conditions, 95% of the data will lie within the ± 2σ range.

Measurements—after removal of natural diurnal cycles (24 h moving average)—that fall outside this interval are considered meteorological anomalies, potentially indicating transient weather events or atmospheric disturbances.

In the context of radon anomaly validation, the absence of concurrent meteorological anomalies beyond the 2σ threshold provides strong evidence that the radon deviation is not meteorologically driven. This reinforces the hypothesis that the radon anomalies are of geophysical origin, potentially linked to subsurface stress accumulation and seismic activity.

Evaluation method of true -false positive and detected-missed event

To evaluate the predictive capability of radon anomalies in relation to seismic events, each detected anomaly is assessed based on its temporal and spatial proximity to an earthquake. The spatial influence of a seismic event is determined using the strain radius (SR) formula proposed25:

where M is the moment magnitude of the earthquake.

For the correlation analysis, only seismic events whose epicentral distance from the radon monitoring station is less than the corresponding strain radius are considered. It was observed that seismic events typically occur within 3 to 4 days following the initiation of the dilatancy phase, which is identified by the radon peak during anomaly progression13,15.

Based on this framework:

-

An anomaly is classified as a True Positive (TP) if it occurs within 100 h before a seismic event and falls within the event’s strain radius.

-

An anomaly is classified as a False Positive (FP) if it does not meet both criteria.

To minimize false positives caused by short-term meteorological fluctuations, only anomalies with a signal duration exceeding 12 h are considered valid.

A detected event is defined as an earthquake that is preceded by at least one qualifying radon anomaly recorded by a monitoring station within the event’s strain radius. In contrast:

-

A Missed Event refers to an earthquake that occurs without any prior anomaly detected within the relevant strain radius.

-

Filtered Events represent cases where an operational radon observatory was within the strain radius, but no qualifying anomaly remained after the application of meteorological and signal-duration filters.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Crosetto, S. et al. Searching for the 1912 Maymyo earthquake: New evidence from paleoseismic investigations along the Kyaukkyan Fault, Myanmar. Quatern. Int. 532, 75–86 (2019).

Tsutsumi, H. & Sato, T. Tectonic geomorphology of the southernmost Sagaing fault and surface rupture associated with the May 1930 Pegu (Bago) earthquake, Myanmar. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 99, 2155–2168 (2009).

Howard, S. & Krishna, G. Myanmar junta blocking aid as earthquake death toll nears 3000. Preprint at (2025).

Xiong, X. et al. Coulomb stress transfer and accumulation on the Sagaing Fault, Myanmar, over the past 110 years and its implications for seismic hazard. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 4781–4789 (2017).

Wang, Y., Sieh, K., Tun, S. T., Lai, K. & Myint, T. Active tectonics and earthquake potential of the Myanmar region. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 119, 3767–3822 (2014).

G, M. I., F, B. A., G, M. P., Sebastian, G. & Sarah, T. The dilatancy–diffusion hypothesis and earthquake predictability. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 367, 215–230 (2012).

Hammond, A. L. Earthquake predictions: Breakthrough in theoretical insight?. Science 1979(180), 851–853 (1973).

Petraki, E. et al. Radon-222: a potential short-term earthquake precursor. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 6, 1 (2015).

Baskaran, M. Radon as a Tracer for Earthquake Studies. in 205–228 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21329-3_10.

Park, S. K. Precursors to earthquakes: Seismoelectromagnetic signals. Surv. Geophys. 17, 493–516 (1996).

Lott, D. F., Hart, B. L. & Howell, M. W. Retrospective studies of unusual animal behavior as an earthquake predictor. Geophys. Res. Lett. 8, 1203–1206 (1981).

Filizzola, C., Pergola, N., Pietrapertosa, C. & Tramutoli, V. Robust satellite techniques for seismically active areas monitoring: a sensitivity analysis on September 7, 1999 Athens’s earthquake. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 29, 517–527 (2004).

Scholz, C. H., Sykes, L. R. & Aggarwal, Y. P. Earthquake prediction: A physical basis: Rock dilatancy and water diffusion may explain a large class of phenomena precursory to earthquakes. Science 1979(181), 803–810 (1973).

Main, I. G., Bell, A. F., Meredith, P. G., Geiger, S. & Touati, S. The dilatancy-diffusion hypothesis and earthquake predictability. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 367, 215–230 (2012).

Sahoo, B. K. et al. A sensitive system based on radon amplification at soil-air interface: Aiming to advance earthquake precursor research. J. Environ. Radioact. 278, (2024).

BIS. 2002 Criteria for Earthquake Resistant Design of Structure. Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi. Doc. No. CED-39 (7231),(Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2006) (1893).

Bansal, B. K. et al. National seismological network in India for real-time earthquake monitoring. Seismol. Res. Lett. 92, 2255–2269 (2021).

Singh, S., Jaishi, H. P., Tiwari, R. P. & Tiwari, R. C. A study of variation in soil gas concentration associated with earthquakes near Indo-Burma Subduction zone. Geoenviron. Disast. 3, 1–8 (2016).

Thuamthansanga, T., Sahoo, B. K. & Tiwari, R. C. Study of pre-seismic thoron anomaly using empirical mode decomposition based Hilbert-Huang transform at Indo-Burman subduction region. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 330, 1571–1582 (2021).

Siino, M., Scudero, S., Cannelli, V., Piersanti, A. & D’Alessandro, A. Multiple seasonality in soil radon time series. Sci. Rep. 9, 8610 (2019).

Sahoo, S. K., Katlamudi, M. & Pedapudi, C. S. Multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis of soil radon in the Kachchh Region of Gujarat, India: A case study of earthquake precursors. Physica A 637, 129582 (2024).

Ghosh, D., Deb, A. & Sengupta, R. Anomalous radon emission as precursor of earthquake. J. Appl. Geophys. 69, 67–81 (2009).

Walia, V. et al. Earthquake precursory study using decomposition technique: time series soil radon monitoring data from the San-Jie Station in Northern Taiwan. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-023-09187-7 (2023).

Fenga, L. Prediction of Noisy ARIMA Time Series via Butterworth Digital Filter. in Advances in Time Series Analysis and Forecasting: Selected Contributions from ITISE 2016 3 173–196 (Springer, 2017).

Dobrovolsky, I. P., Zubkov, S. I. & Miachkin, V. I. Estimation of the size of earthquake preparation zones. Pure Appl. Geophys. 117, 1025–1044 (1979).

King, C.-Y. Radon emanation on San Andreas fault. Nature 271, 516–519 (1978).

Iakovleva, V. S. & Ryzhakova, N. K. A method for estimating the convective radon transport velocity in soils. Radiat. Meas. 36, 389–391 (2003).

Singh, S., Jaishi, H. P., Tiwari, R. P. & Tiwari, R. C. Time series analysis of soil radon data using multiple linear regression and artificial neural network in seismic precursory studies. Pure Appl. Geophys. 174, 2793–2802 (2017).

Ramola, R. C., Prasad, Y., Prasad, G., Kumar, S. & Choubey, V. M. Soil-gas radon as seismotectonic indicator in Garhwal Himalaya. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 66, 1523–1530 (2008).

Sahoo, B. K. & Mayya, Y. S. Two dimensional diffusion theory of trace gas emission into soil chambers for flux measurements. Agric. For. Meteorol. 150, 1211–1224 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge the motivation and encouragement given by former Directors of Health, Safety and Environment Group, Dr. K. S. Pradeepkumar and Shri Suresh Babu to pursue this project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Department of Atomic Energy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BK Sahoo contributed in conceptualisation, model formulation, system design, experiments, data analysis, and drafting of original manuscript; BK Sapra contributed in project design, visualisation, data analysis, reviewing and editing of manuscript; Arshad Khan contributed in project design. MP Ratheesh contributed in system design and editing of schematics and drawing of figures; DH Kumbhar and JJ Gaware assisted in experimental design, SD Kanse contributed in reviewing and editing of manuscript, Sumitra Phanjoubam contributed in operation and maintenance of radon observatory. DK Aswal contributed in overall reviewing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahoo, B.K., Sapra, B.K., Khan, A. et al. A persistent radon anomaly signal preceding the destructive 7.7 Mw earthquake in Myanmar on March 28, 2025. Sci Rep 15, 25447 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10632-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10632-8