Abstract

To investigate the germplasm differences between northern and southern populations of Parabramis pekinensis and analyze their genetic diversity and population structure, this study employed 10 developed microsatellite markers to analyze 133 individuals collected from the Yangtze River Basin (Jiangsu JS, Hunan HN) and the Amur River Basin (Jilin JL, Heilongjiang HLJ). The HLJ population is considered a wild stock, while the other three groups are classified as cultured populations. The analysis revealed that four Parabramis pekinensis populations exhibited high levels of genetic diversity, with polymorphic information content (PIC) ranging from 0.5130 to 0.6142. A total of 249 alleles were detected, among which the HN population showed the highest genetic diversity (Na = 8.0 ± 4.59). The analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) revealed significant genetic differentiation among populations, with 34% of gene variation attributed to inter-population differences (Fst = 0.337). The UPGMA clustering and STRUCTURE analysis (optimal K = 3) grouped the JL and HLJ populations into a single cluster, which subsequently merged with the JS population to form a larger clade. In contrast, the HN population was distinctly separated as an independent branch. The study demonstrates that the HN population of P. pekinensis should be prioritized for conservation as a distinct genetic unit, with the enhancement of habitat connectivity among northern populations could effectively mitigate genetic diversity loss. These findings provide a scientific foundation for the preservation of P. pekinensis germplasm resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parabramis pekinensis is classified within the order Cypriniformes, family Cyprinidae, subfamily Cultrinae, and genus Parabramis. This species is distributed extensively, with a primary habitat in rivers and lakes within China’s major river systems, including the Amur River basin, the Yangtze, and the Pearl Rivers. Additional occurrences have been reported in North Korea and Russia. P. pekinensis is highly regarded for its tender and delicate flesh, exquisite flavour, and high nutritional value, thus classifying it as a premium freshwater fish with significant market potential. The genetic diversity of P. pekinensis has been subject to a substantial decline as a consequence of habitat fragmentation. As a pelagic-egg spawning species, its reproductive capacity is significantly diminished by the development of hydraulic infrastructure, thereby posing a substantial threat to the viability of its population. Furthermore, practices such as lake reclamation for farmland, overfishing, unsustainable artificial domestication, and unscientific management have collectively led to a drastic decline in the germplasm resources of P. pekinensis, causing severe erosion of its genetic diversity.

In recent years, research on P. pekinensis has focused on the mechanisms of gonadal development1, external morphological characteristics2,3, dynamics of trophic niches4, and structure of gut microbial communities5. However, systematic investigations into its germplasm resources remain relatively insufficient, particularly regarding the evaluation of genetic diversity and characterization of the genetic structure among different regional populations of P. pekinensis, for which there is currently a paucity of relevant reports.

Microsatellite markers are defined by three characteristics: codominant inheritance, high mutation rates and locus-specific variations. The capable to discern subtle population differentiation with a high degree of precision has led to the extensive utilisation of these methods in the evaluation of genetic structure and diversity in a multitude of fish species6,7,8,9,10. In recent years, microsatellite markers have been successfully developed and used to evaluate the genetic diversity of various cyprinid species11,12,13,14. However, there are currently no published microsatellite markers specifically available for the P. pekinensis.

Materials and methods

Ethic statement

All sampled Parabramis pekinensis were neither endangered nor protected species. According to Chinese regulations, no special permits are required for catching Parabramis pekinensis in natural waters. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin Fisheries Research Institute (Approval No. JFRIAEC-2023-015), and all procedures were conducted in strict compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All experiments were performed in accordance with national laws and institutional guidelines for animal care and use established by Jilin Fisheries Research Institute.

Collection of experimental materials

A total of 133 P. pekinensis individuals were collected from wild samples in Fuyuan County, Heilongjiang Province (48°21′18.062″ N, 134°16′32.007″ E) (HLJ, n = 14); cultured samples in Jilin City, Jilin Province (43°57′2.200″ N,126°41′23.087″ E) (HLJ, n = 14) (JL, n = 52); cultured samples in Jingjiang County, Jiangsu Province (31°55′1.878″ N, 120°8′47.480″ E) (JS, n = 22), and cultured samples in the Hunan Academy of Aquatic Sciences (28° 16′ 14.833″ N, 113°6′19.459″ E) (HN, n = 45). The average overall length was 9.78 cm. The average body length was 7.92 cm, the average height was 2.55 cm and the average body mass was 8.07 g. The HLJ and JL populations were from the Heilongjiang River system and the HN and JS populations were from the Yangtze River system. The collected fin tissues were preserved by immersion in 95% ethanol. The DNA was extracted using the QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit according to the instructions. Its integrity was verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and its concentration and purity were detected using the NanoDrop 2000 Micro UV–Vis Spectrophotometer. The DNA was diluted to 50 ng/µL, and then stored at − 20 °C for storage.

Microsatellite primer design and screening

Using the publicly available reference genome GCA_018812025.1 of Megalobrama amblycephala from the NCBI database. SSR Hunter was used to search for microsatellite regions. Sequences with more than eight trinucleotide repeats were selected as candidate sequences. Primers were designed using Primer Premier 5.0. The primers were synthesized by Beijing Le8 Technology Co. The PCR reaction system contained a total volume of 25 µL, including 2 µL (50 ng) of DNA template, 0.5 µL (20 µM) of primers, 0.5 µL of dNTPs, 2.5 µL of 10 × PCR buffer, 0.5 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (Takara) and 18.5 µL of ddH2O. Amplification was performed using a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 manufactured by PerkinElmer, USA. The PCR reaction conditions were as follows: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles, each consisting of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 56 °C and 30 s at 72 °C and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Forty-eight pairs of microsatellite primers were obtained.

Three samples were selected from each population to screen the polymorphic primers. PCR reaction system was 15 µL, including 0.8 µL of TP-M13 (5 mM), 1 µL of primers (5 mM), 7.5 µL of PCR Mix, 1.5 µL of DNA template, and ddH2O was added to 15 µL. Amplification was carried out by TP-M13-SSR fluorescence labeling PCR. The PCR reaction program was as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min; 5 cycles, (each cycle denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing temperature starting from 60℃, lowering 1 °C to 55 °C for each cycle, extension at 72 °C for 30 s); 30 standard cycles (30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, 30 s at 72 °C); 10 labeling cycles (30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 53 °C, 30 s at 72 °C), and final extension at 60 °C for 30 min to ensure product integrity. After the PCR reaction, the amplification products were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis, and those with the target bands were selected for detection on the 3730xl Genetic Analyzer. The results of electrophoresis detection were analyzed with Genemapper 4.0 and to Size results, and then the results of each pair of primers were analyzed, if the number of alleles was greater than or equal to three, it indicated that the primer was polymorphic, and it could be used as molecular markers for genetic diversity analysis at a later stage.

Finally, 10 pairs of microsatellite primers with good polymorphism were selected and detailed sequence information is listed in Table 1(Accession number: BankIt2968220 CCB-2 PV765790, BankIt2968220 CCB-3 PV765791, BankIt2968220 CCB-5 PV765792, BankIt2968220 CCB-6 PV765793, BankIt2969170 CCB-7 PV771622, BankIt2969170 CCB-10 PV771623, BankIt2969170 CCB-11 PV771624, BankIt2969170 CCB-13 PV771625, BankIt2969170 CCB-14 PV771626 and BankIt2969170 CCB-15 PV771627). The collected samples were subjected to PCR amplification, the PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and the genotypes of each SSR locus of each sample were detected using a 3730xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Data analysis

We used POPGENE 3.215 to analyse the genotypes of different loci across populations to calculate the following parameters for each microsatellite locus: the number of alleles (Na), the effective number of alleles (Ne), the observed heterozygosity (Ho), the expected heterozygosity (He), Shannon’s information index (I), Nei’s standard genetic distance, the inbreeding coefficient (Fis), the fixation index (Fst), the gene flow (Nm) and the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test (p-value), We also constructed phylogenetic trees among populations based on Nei’s genetic distance. Polymorphic information content (PIC) was calculated using Cervus 3.0.716. Molecular variance analysis (AMOVA) was conducted using Arlequin version 3.5.2.217. The GenAlEx 6.5 Excel add-in18 was employed for chi-square tests of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, as well as principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on pairwise genetic distances among populations and individuals.

Population genetic structure was analyzed using Structure Selector19, which determined the optimal K value based on two criteria: Mean lnP(K)20 and ΔK21. The integrated CLUMPAK program was then used to generate the final graphical results.

Results and analysis

SSR genotyping results

Genomic DNA was extracted from 133 P. pekinensis tissue samples. This was followed by PCR amplification using 10 microsatellite primer pairs. The amplification products were separated by capillary electrophoresis, and genotypes were analyzed using GeneMapper software. Figure 1 displays the allele peak profiles of selected loci in representative individuals.

Genetic diversity

We evaluated the genetic diversity of four P. pekinensis populations using 10 microsatellite primer pairs. We analyzed the number of alleles (Na), the effective number of alleles (Ne), the observed heterozygosity (Ho), the expected heterozygosity (He), the Shannon’s index (I), Nei’s standard genetic distance, and polymorphic information content (PIC) (Table 2). A total of 249 alleles (Na) were detected, with an average of 6.225 per locus. The He values ranged from 0.0714 to 0.9656, and I values from 0.1541 to 2.7502. Nei’s genetic distance ranged from 0.0689 to 0.9311. The average I values for all populations exceeded 1, indicating high genetic diversity. PIC values calculated using specialized software showed a maximum of 0.9268, a minimum of 0.0665, and an average of 0.5554 (PIC > 0.5). Notably, two microsatellite loci (CCB-7, CCB-13) exhibited PIC values below 0.3, whereas the remaining loci showed PIC values above 0.3, demonstrating that most markers were highly polymorphic.

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) tests were performed on the 10 microsatellite loci across the four populations. Among these, 27 loci conformed to HWE (p > 0.05), while 13 loci significantly deviated (p < 0.05).

Genetic structure

The analysis of genetic differentiation coefficients (Fst) and gene flow (Nm) between pairwise populations of four Parabramis pekinensis populations (Table 3) revealed that Nm ranged from 1.3428 to 3.3530. Nm was greater than 1 between populations, with the highest gene flow observed between the HLJ and JL populations (3.3530), and the lowest between the HN and JS populations (1.3428). The genetic differentiation coefficients (Fst) were less than 0.15 for other population pairs except for the HN-JS and HN-JL population pairs.

The genetic similarity coefficients and genetic distances between the four P. pekinensis populations ranged from 0.4194 to 0.8336 and 0.1819 to 0.9567, respectively (Table 4). The HLJ and JL populations exhibited the highest genetic similarity (0.8336) and the smallest genetic distance (0.1819), while the HN and JS populations showed the lowest genetic similarity (0.3841) and the largest genetic distance (0.9567). Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) revealed that 34% of the genetic variation originated from differences between populations, while 66% stemmed from variation within populations (Table 5). These results suggest significant genetic differentiation between the four P. pekinensis populations, to varying extents.

The phylogenetic tree constructed using UPGMA method and based on Nei’s genetic distance (Fig. 2) showed that the four P. pekinensis populations share a common ancestral origin and clustered into two major groups. Specifically, the JL and HLJ populations first grouped together, then clustered with the JS population, while the HN population formed a distinct group. The results of Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) are shown in Fig. 3, no significant genetic clustering was observed.

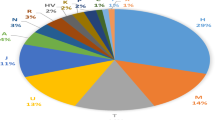

Genetic clustering analysis

The optimal genetic clustering number (K = 3) was determined by Structure Harvester analysis, revealing that the four P. pekinensis populations were derived from three distinct ancestral gene pools (Fig. 4). Additionally, based on Q-value statistics of the population probability distribution of the 133 samples, shows that these populations can be categorized into three taxa: the Jiangsu population, the Heilongjiang and Jilin populations, and the Hunan population (Fig. 5).

Genetic structure analysis of individuals from four P. pekinensis populations under K = 3 hypothesis. Each vertical bar represents an individual, with different colors indicating the proportional contribution of each K genetic cluster to the individual’s genotype: 1. JS population, 2. HLJ population, 3. JL population, and 4. HN population.

Discussion

Genetic diversity analysis

Genetic diversity is defined as the degree of genetic variation among individuals or populations within a species. It is an important resource for species to cope with environmental change and human interference. Higher genetic diversity has been demonstrated to provide populations with richer adaptive variation, thus enhancing their survival and evolutionary potential in dynamic environments22,23,24. In this study, we obtained discrete allelic data for 133 Parabramis pekinensis accessions from 4 populations based on analysis using 10 microsatellite markers. The average polymorphic information content (PIC) for each population ranged from 0.5130 to 0.6142. This was higher than that reported for other carp species in the Yangtze River basin, such as the bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis)25,26 and grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)27. This suggests that the P. pekinensis population may have greater adaptive potential, which is highly valuable for breeding and resource conservation purposes. We evaluated the genetic diversity of P. pekinensis in terms of allelic richness (Na), heterozygosity (He), and allelic diversity (I). In the present study, the mean genetic parameters detected at each microsatellite locus (Na = 6.2250, He = 0.5924, I = 1.2258) indicated that the genetic diversity level of P. pekinensis was slightly lower than that of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) (Na = 10.000, He = 0.734, I = 1.755)28, a closely related species from the genus Megalobrama. Furthermore, compared to other aquaculture fish species, the genetic diversity of P. pekinensis was higher than that of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) (Na = 6.571, He = 0.484, I = 0.988)29 but lower than that of spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus) (Na = 28.7273, He = 0.8248, I = 2.3202)30.

In our study, significant genetic diversity differences were detected among the four geographically distinct populations of P. pekinensis. In biostatistics and sampling surveys, a sample size of 30 is conventionally used as the threshold to distinguish between large and small samples. Although the sample sizes varied across populations in this study, the HLJ and JS populations had fewer than 30 individuals. Nevertheless, these samples were sufficient to broadly reflect the genetic resource status of their respective regional groups. Due to the influence of sample size on the number of alleles (Na), expected heterozygosity (He) is more commonly used to measure genetic diversity within populations31. When He values range between 0.500 and 0.800, the population can be considered to possess relatively high genetic diversity32. In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the HN population displayed the highest level of genetic variability (Na = 8.0000, He = 0.6657, I = 1.4291), followed sequentially by the HLJ and JL populations, with the JS population exhibiting the lowest diversity. The complex hydrological conditions characteristic of the middle and lower Yangtze River basin likely generate heterogeneous selective pressures that maintain multiple adaptive alleles through balancing selection33,34, potentially accounting for the elevated genetic diversity observed in the HN population. The HLJ population (Na = 6.2000, He = 0.6204, I = 1.3041) and JL population (Na = 6.2000, He = 0.5657, I = 1.1612) exhibited similarly high levels of genetic diversity. This genetic pattern may be attributed to the relatively intact aquatic ecosystem and lower intensity of anthropogenic disturbances characteristic of the Heilongjiang River basin. In contrast, the JS population exhibited significantly lower genetic diversity parameters (Na = 4.5000, He = 0.5314, I = 1.0090). As a major aquaculture region35, the cultivation of P. pekinensis in Jiangsu Province may have long relied on a limited number of high-quality broodstocks for artificial propagation. This intensive artificial selection pressure likely contributed to the reduced genetic diversity observed in the Jiangsu population, a phenomenon consistent with the findings of Zhang et al.36 regarding the congeneric M. amblycephala. Genomic analyses further revealed that farmed populations of M. amblycephala in Jiangsu experienced significant declines in key genetic diversity indices, including allele number (Na) and heterozygosity (He), following seven generations of artificial selection.

It is particularly important to emphasize that the neutral theory of molecular evolution provides an incomplete explanation for genetic diversity patterns. This theory originated from the flawed “molecular clock hypothesis”, which fundamentally misinterpreted the phenomenon of genetic equidistance. Recent empirical studies have conclusively refuted the neutral theory37. A recent seminal study has demonstrated that the human mitochondrial DNA genome is predominantly functional rather than neutral, providing direct empirical evidence that falsifies the neutral theory of molecular evolution38. While short tandem repeats (STRs) were originally postulated to be evolutionarily neutral, emerging evidence demonstrates their functional capacity to bind transcription factors25. This paradigm shift has contributed to the development of novel theoretical frameworks, most notably the Maximum Genetic Diversity Theory, which is progressively superseding the neutral theory of molecular evolution39.

The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium conditions are: infinitely large groups; random mating; there are no mutations; there is no choice; there is no migration; there is no genetic drift (random fluctuations in gene frequencies within a small population)40. In practical applications, populations rarely meet all ideal assumptions. The deviation of genotype distribution from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium is typically measured using P-values, where lower P-values indicate greater deviations. In this study, there may be insufficient sample size, wrong typing, or biased sample selection41, and only 27 of the 40 polymorphic loci met the H-W equilibrium.

Genetic structure analysis

Maintaining high genetic diversity within biological populations plays a crucial role in their environmental adaptability. Specifically, parameters such as the fixation index (FST) can effectively reflect the level of genetic differentiation among populations, and these differences are often closely associated with ecological adaptation processes42,43. The molecular variance analysis (AMOVA) in this study revealed that 34% of the genetic variation occurred among populations (fixation index FST = 0.337, P < 0.001), while the remaining 66% of variation was distributed within populations (Table 5). This differentiation pattern aligns well with the ecological characteristics of habitat fragmentation in freshwater fishes, likely resulting from dispersal limitations and hydrological connectivity constraints44. Current research demonstrates significant variation in FST values (0.0725–0.1790) among the four geographically distinct P. pekinensis populations, indicating varying degrees of genetic differentiation between these groups. The HN population exhibited relatively high pairwise FST values (0.1570–0.1790) compared to other populations, which may be attributed to its geographical location. The Yangtze River likely serves as a natural barrier that restricts gene flow between the southern HN population and northern populations (JS, JL, HLJ). A similar phenomenon was reported by Wang et al.30 in Large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) populations from the South China Sea, where the Qingdao (QD) population, though geographically located in northern waters, genetically clustered with southern populations due to restricted gene flow caused by natural barriers formed by the Yellow Sea and East China Sea. The JS, JL, and HLJ populations exhibited low genetic differentiation but strong genetic admixture, as evidenced by their interpopulation FST values (0.0694–0.1133), gene flow estimates (1.9566–3.3530), and Nei’s genetic similarity coefficients (0.6756–0.8336). Notably, the JL and HLJ populations showed the highest Nei’s genetic similarity (0.8336) and smallest genetic distance (0.1819), likely attributable to their hydrological connectivity—the JL population inhabits Songhua Lake, a tributary of the Heilongjiang River system, which probably facilitates gene exchange between these populations.

The UPGMA phylogenetic tree based on Nei’s genetic distance (Fig. 1) clustered all P. pekinensis specimens into three major clades: one comprising the northeastern populations (JL and HLJ), one consisting of the JS population, and one containing the HN population. This clustering pattern is consistent with the population structure analysis (K = 3) (Figs. 4, 5). In conclusion, we recommend designating the HN population as a distinct Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) for prioritized conservation, while simultaneously enhancing ecological connectivity among northern populations’ habitats to maintain their genetic diversity levels. However, significant discrepancies were observed among the phylogenetic tree, population structure analysis, and PCA results. These inconsistencies may stem from the limited genetic differentiation and close genetic distances among individuals. Furthermore, methodological differences between phylogenetic reconstruction and principal component analysis could contribute to this divergence45,46. The underlying causes of these discordant patterns warrant further investigation.

Conclusion

This study systematically analyzed the genetic diversity and population structure of four geographic populations (JS, HN, JL, HLJ) of P. pekinensis using 10 microsatellite markers. The results demonstrated that P. pekinensis populations collectively maintained relatively high genetic diversity (mean PIC = 0.5130–0.6142). Specifically, the HN population exhibited the highest genetic variation (Na = 8.0000, He = 0.6657, I = 1.4291), followed by HLJ and JL populations, while the JS population showed the lowest diversity levels. Both population structure analysis (K = 3) and UPGMA phylogenetic tree consistently identified three distinct clusters: northeastern populations (JL and HLJ) forming one branch, JS population as a separate branch, and HN population as an independently diverged lineage. The study revealed close genetic relationships between the JS population and northeastern populations (JL/HLJ), indicating substantial historical gene flow among these groups. The study recommends designating the HN population as a distinct Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) for prioritized conservation due to its unique genetic divergence, while simultaneously enhancing habitat connectivity among northern populations (JS, JL, HLJ) to maintain their genetic diversity. These findings provide crucial scientific foundations for the conservation and management of P. pekinensis germplasm resources.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gu, H., Feng, Y. & Yang, Z. Differential study of the Parabramis pekinensis intestinal microbiota according to different gonad development stages. Fish. Sci. 88, 721–731 (2022).

Xu, W. et al. Effects of morphological traits on body weight and analysis of growth-related genes of Parabramis pekinensis at different ages. BMC Zool. 8, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-023-00174-9 (2023).

Tian, X., Gao, P., Xu, Y., Xia, W. & Jiang, Q. Reduction of biogenic amines accumulation with improved flavor of low-salt fermented bream (Parabramis pekinensis) by two-stage fermentation with different temperature. Food Biosci. 44, 101438 (2021).

Luo, S. et al. Formation of adaptive trophic niches of Euryphagous fish species in response to off-seasonal water level regulation in Hongze lake. Anim. Basel 15, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15010059 (2024).

Gu, H., Feng, Y., Zhang, Y., Yin, D. & Tang, W. Differential study of the Parabramis pekinensis intestinal microbiota according to different habitats and different parts of the intestine. Ann. Microbiol. 71, 1–11 (2021).

Abbas, K., Zhou, X., Li, Y., Gao, Z. & Wang, W. Microsatellite diversity and population genetic structure of yellowcheek, Elopichthys bambusa (Cyprinidae) in the Yangtze River. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 38, 806–812 (2010).

Zhu, W. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) from the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River revealed using microsatellite markers. Aquac. Rep. 27, 101377 (2022).

Zhong, L. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco from five lakes in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, China, based on mitochondrial DNA control region. Mitochondrial Dna J. Dna Mapp. Seq. Anal. 24, 552–558 (2013).

Nikolic, N., Fève, K., Chevalet, C., Høyheim, B. & Riquet, J. A set of 37 microsatellite DNA markers for genetic diversity and structure analysis of Atlantic salmon Salmo salar populations. J. Fish Biol. 74, 458–466 (2009).

Pacheco-Almanzar, E., Ramírez-Saad, H., Velázquez-Aragón, J. A., Serrato, A. & Ibáez, A. L. Diversity and genetic structure of white mullet populations in the Gulf of Mexico analyzed by microsatellite markers. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 198, 249–256 (2017).

Kim, K. R., Kwak, Y. H., Sung, M. S., Cho, S. J. & Bang, I. C. Population structure and genetic diversity of the endangered fish black shinner Pseudopungtungia nigra (Cyprinidae) in Korea: A wild and restoration population. Sci. Rep. 13, 9692 (2023).

Du, R., Zhang, D., Wang, Y., Wang, W. & Gao, Z. Cross-species amplification of microsatellites in genera Megalobrama and Parabramis. J. Genet. 92, e106-109 (2013).

Qianqian, Z., Jie, C., Xiayun, J. & Shuming, Z. Establishment of DNA fingerprinting and analysis on genetic structure of different Parabramis and Megalobrama populations with microsatellite. J. Fish. China 38, 15–22 (2014).

Lin, L. I. et al. Establishment of microsatellite identification on there Culterinae fishes in Pearl River. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 41, 102–101 (2014).

Yeh, F. C. & Boyle, T. J. B. Population genetic analysis of codominant and dominant markers and quantitative traits. Belg. J. Bot. 129, 157 (1997).

Kalinowski, S. T. Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol. Ecol. 16, 1099–1106 (2010).

Excoffier, L. & Lischer, H. E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x (2010).

Smouse, P. E., Whitehead, M. R. & Peakall, R. An informational diversity framework, illustrated with sexually deceptive orchids in early stages of speciation. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 1375–1384. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12422 (2015).

Li, Y. L. & Liu, J. X. StructureSelector: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 176–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12719 (2018).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/155.2.945 (2000).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x (2005).

de Lafontaine, G., Napier, J. D., Petit, R. J. & Hu, F. S. Invoking adaptation to decipher the genetic legacy of past climate change. Ecology 99, 1530–1546. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2382 (2018).

Lima, J. S., Ballesteros-Mejia, L., Lima-Ribeiro, M. S. & Collevatti, R. G. Climatic changes can drive the loss of genetic diversity in a Neotropical savanna tree species. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4639–4650. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13685 (2017).

Onogi, A., Shirai, K. & Amano, T. Investigation of genetic diversity and inbreeding in a Japanese native horse breed for suggestions on its conservation. Anim. Sci. J. 88, 1902–1910. https://doi.org/10.1111/asj.12867 (2017).

Horton, C. A. et al. Short tandem repeats bind transcription factors to tune eukaryotic gene expression. Science 381, 18 (2023).

Farrington, H. L., Edwards, C. E., Bartron, M. & Lance, R. F. Phylogeography and population genetics of introduced Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and Bighead Carp (H. nobilis) in North America. Biol. Invasions 19, 1–23 (2017).

Li, D. et al. A multiplex microsatellite PCR method for evaluating genetic diversity in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Aquac. Fish. 3, 238–245 (2018).

Dong, F. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) in the Yangtze River Basin: Implications for conservation and utilization. Aquac. Rep. 35, 101925 (2024).

Du, J. et al. Genetic diversity analysis and DNA fingerprinting of different populations of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) in China with fluorescence-labeled microsatellite markers. BMC Genomics 26, 1–15 (2025).

Wang, W., Ma, C., Ouyang, L., Chen, W. & Ma, L. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of Lateolabrax maculatus from Chinese coastal waters using polymorphic microsatellite markers. Sci. Rep. 11, 15260 (2021).

Kalinowski, S. T. hp-rare 1.0: A computer program for performing rarefaction on measures of allelic richness. Mol. Ecol. Notes 5, 187–189 (2010).

Takezaki, N. & Nei, M. Genetic distances and reconstruction of phylogenetic trees from microsatellite DNA. Genetics 144, 389–399 (1996).

Shen, Y. et al. Important fish diversity maintenance status of the tributaries in a hotspot fish conservation area in the upper Yangtze River revealed by eDNA metabarcoding. Sci. Rep. 14, 24128. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75176-9 (2024).

Chen, H. J., Wang, D. Q., Duan, X. B., Chen, D. Q. & Li, Y. Genetic diversity of white bream, Parabramis pekinensis from the middle Yangtze river. Chin. J. Ecol. 35, 2175 (2016).

Hu, M., Wang, C., Liu, Y., Zhang, X. & Jian, S. Fish species composition, distribution and community structure in the lower reaches of Ganjiang River, Jiangxi, China. Sci. Rep. 9, 10100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46600-2 (2019).

Tang, S. J., Si-Fa, L. I., Cai, W. Q. & Zhao, Y. Microsatellite analysis of variation among wild, domesticated, and genetically improved populations of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Zool. Res. 35, 30–39 (2014).

Lynch, M., Wei, W., Ye, Z. & Pfrender, M. The genome-wide signature of short-term temporal selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, 10 (2024).

Lake, N. J. et al. Quantifying constraint in the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 635, 390–397 (2024).

Huang, Y. M., Xia, M. Y. & Huang, S. Evolutionary process unveiled by the maximum genetic diversity hypothesis. Hereditas 35, 599–606 (2013).

Hardy, G. H. Mendelian proportions in a mixed population. Science 28, 49–50. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.28.706.49 (1908).

Bucklin, K. A. et al. Assessing genetic diversity of protected coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) populations in California. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 64, 30–42 (2007).

Wang, L., Meng, Z., Liu, X., Zhang, Y. & Lin, H. Genetic diversity and differentiation of the orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) between and within cultured stocks and wild populations inferred from microsatellite DNA analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 4378–4394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms12074378 (2011).

Wright, S. Evolution and the genetics of populations. Vol. 1. Genetic and biométrie foundations. (Evolution and the genetics of populations, 1968).

Knowles, L. L. et al. Genomic signatures of paleodrainages in a freshwater fish along the southeastern coast of Brazil: genetic structure reflects past riverine properties. Hered. Int. J. Genet. 119, 287–294 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Analysis of the genetic structure and diversity of upland cotton groups in different planting areas based on SNP markers. Gene 809, 146042 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Geographic population genetic structure and diversity of Sophora moorcroftiana based on genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS). PeerJ 8, e9609. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9609 (2020).

Funding

The funding was provided by National Freshwater Aquatic Germplasm Resource Bank (Grant No. FGRC: 18537), Basic Scientific Research Fund Project of Provincial Public Welfare Research Institutes in Jilin Province (Grant No. JSCYJK202301), Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Program (Garnt No. 20220202064NC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L .and C.Y .designed the research framework and wrote the main manuscript text. H.L.participated in the collection of Parabramis pekinensis specimens. J.X.participated in the collection of Parabramis pekinensis specimens. L.P. and C.W.participated in the cultivation of experimental fish stocks. L.H.and Z.Y. and L.J. participated in data recording.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Yan, C., Li, H. et al. Genetic diversity analysis of four Parabramis pekinensis populations based on microsatellite markers. Sci Rep 15, 26694 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10664-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10664-0