Abstract

Cold pressing is one of the most common methods of extracting oil from seeds, generating by-products in the form of meals that are often discarded as waste. Given the large quantities of these meals and the presence of valuable compounds, a thorough investigation of their nutritional value and potential applications is essential. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the residual oil, total phenol and flavonoid content, phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, as well as the ash, carbohydrate, protein, and mineral nutrient content of 15 commercial and non-commercial oilseed meals. The results showed that Sesamum indicum meal had the highest residual oil content (17.86 ± 2.4%). Among the meals studied, Pistacia atlantica showed the highest concentrations of phenols (17.67 ± 0.69 mg GAL/g meal) and flavonoids (3.07 ± 0.003 mg QE/g meal). Also, it exhibited the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity, with an IC50 value of 33.11 ± 1.41 µg/mL. Quantitative HPLC analysis showed that P. atlantica and Helianthus annuus meals were particularly rich in quercetin (37.20 ± 2.97 mg/g meal) and rosmarinic acid (46.67 ± 3.32 mg/g meal), respectively, suggesting that their antioxidant properties may be due to these compounds. In terms of macronutrients, the highest carbohydrate content was observed in Arachis hypogaea (37.92 ± 0.11%), while H. annuus meal had the greatest protein concentration (45.12 ± 1.83%). Mineral analysis showed that Prunus armeniaca, H. annuus, and Chrozophora tinctoria meals were the richest sources of potassium (1.73 ± 0.04%), phosphorus (0.60 ± 0.03%), and calcium (16.20 ± 0.09%), respectively. Furthermore, the highest magnesium content (0.29 ± 0.00%) was found in Cucurbita pepo and Lallemantia royleana meals. These findings highlight the nutritional and bioactive potential of the meals studied, especially those from P. atlantica, H. annuus, and L. royleana, which contain valuable compounds suitable for applications in food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and other industries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, the by-products and waste from many agricultural and food industries are often incinerated, fed to animals, or used as organic fertilizers. However, these cheap and readily available resources can be processed to produce valuable compounds1,2. One such resource is oilseed meals, which are rich in residual oils, carbohydrates, proteins, bioactive compounds, and minerals3,4,5. Processing these meals for use in various industries, particularly the food and pharmaceutical industries can significantly increase their economic value6,7.

Residual oils are the primary compounds that can be extracted from oilseed meals. Despite extensive oil extraction, a considerable amount of oil remains in the meal. Re-extracting these residual oils allows them to be used in the food, pharmaceutical, and healthcare industries, as well as in the production of biofuels. This approach not only prevents the waste of valuable resources but also increases the economic value of these by-products8.

In addition to residual oils, carbohydrates and proteins are important compounds extracted from oilseed meals. Carbohydrates serve crucial functions in the human body: they provide energy, regulate blood glucose and insulin metabolism, contribute to cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism, and assist in fermentation processes9. Proteins play a key role in building and repairing muscles, bones, and organs, regulating hormones, and maintaining immune system function. For example, Portulaca oleracea seed meal has been reported to contain high levels of protein10. Similarly, Vasudha and Sarla11 demonstrated that Helianthus annuus seed meal is rich in both carbohydrates and proteins. Another study found that Carthamus tinctorius seed meal contained significant amounts of proteins and carbohydrates, with xylose being the dominant carbohydrate12.

The third major group of compounds found in oilseed meals are bioactive compounds, mainly phenolic compounds. These molecules are essential for food quality and safety, influencing color, flavor, and human health13. Oilseed meals can be an excellent source of phenolic compounds with valuable biological properties. For example, research on oil palm waste showed that 2.73 tons of palm meal per hectare contained bioactive phenolic compounds beneficial to human health14. Another study on Cannabis sativa seed meal found high levels of antioxidant phenolic compounds, such as cannabisin B (267 mg/kg), catechin (744 mg/kg), and p-hydroxybenzoic acid (129 mg/kg)15. In research on Brassica napus seed meal, the extract exhibited significant antioxidant properties, with a total peroxyl radical scavenging potential of 27.05 µM Trolox Eq/g, and sinapic acid derivatives amounting of 2533–2702 mg/100 g16. Petropoulos et al.10 also confirmed that P. oleracea seed meal contains significant amounts of phenolic compounds.

Minerals are the fourth category of valuable materials derived from oilseed meals and include essential macro and micronutrients. According to Vasudha and Sarla11, H. annuus seed meal contains valuable minerals such as calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P). Another study by Mansouri et al.12 reported that C. tinctorius seed meal is a rich source of potassium (K), magnesium (Mg) and calcium (Ca).

Despite the potential of oilseed meals, comprehensive studies on the compounds present in meals derived from the most used oilseeds worldwide are still lacking. This study was therefore undertaken to provide information on the valuable compounds in these meals. The findings can increase the economic value of oilseed meals by promoting their processing and reuse in various industries. Specifically, this research evaluated and compared the residual oil, total phenol and flavonoid contents, phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, residual ash, carbohydrates, proteins, and mineral nutrients in 15 commercial and non-commercial oilseed meals.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and solvents used

The chemicals and solvents used for extraction and biological tests were over 98% pure and were purchased from Merck Company (Germany). Phenolic acid standards (gallic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, cinnamic acid, ferulic acid, salicylic acid, and m-coumaric acid) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemical Company (Germany) with a purity of 99%. Methanol HPLC grade (Tedia, Fairfield, Ohio, USA) was used for the HPLC analysis, and water was purified using a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Massachusetts, USA).

In this study, fifteen important commercial and non-commercial oilseeds were investigated. Twelve cultivated plants including Nigella sativa, Brassica napus, Cannabis sativa, Portulaca oleracea, Prunus armeniaca, Helianthus annuus, Lallemantia royleana, Carthamus tinctorius, Arachis hypogaea, Cucurbita pepo, Sesamum indicum, and Linum usitatissimum were collected at the ripe fruit stages from farms the East Azerbaijan, West Azarbaijan, Fars, and Kerman provinces (Table 1). Three uncultivated plants including Pistacia atlantica, Pyrus glabra, and Chrozophora tinctoria were collected from their natural habitat in September of 2022 (Table 1). The collection of plants was based on the IUCN policy statement on research involving species at risk of extinction and the convention on the trade in endangered species of wild Fauna and Flora. Also, the necessary permissions and/or licenses have been obtained for the collection of studied plants. Specimens were identified by Dr. Saeid Hazrati according to Flora Iranica, and the voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University (ASMUH, Table 1). The seeds were dried in shade at 25 °C, and kept in plastic bags. After removal of any waste material, the seeds were dried, to a residual moisture content of between 10% and 12%.

Extraction of oils from meals

A cold pressing method was used for oil extraction. A total of 1000 g of seeds were pressed using a 6YZ180 automatic hydraulic press (Zhengzhou Bafang Machinery and Equipment Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China) at a temperature of 25 °C and a pressure of 50 MPa for 0.5 h to obtain the oil. The weight of the extracted oil was recorded to calculate the oil yield.

For the extraction of oils from the meals obtained by cold pressing, the meals were powdered using an electric blender and sieved through a 1.00 mm granulometric sieve to obtain a uniform particle size. Then, 25 mL of diethyl ether was added to 5 g of the powdered meal and extracted using the vortex method for 5 min. The mixture was then stored in a dark place for 24 h. The sample was centrifuged (Boeco U-320, Hamburg, Germany) at 5000 rpm for 20 min17. After evaporation of the solvent with the nitrogen gas, the oil yield was measured using Eq. (1).

Extraction of free and bound phenolic compounds

To extract the free phenolic compounds, the meals were first defeated. Then, 80% ethanol (10 mL, pH 4.5–5) was added to 1 g of meal powdered, vortexed for 10 min, and then centrifuged for 20 min at 5000 rpm. The supernatant was dried at 60 °C, and the yield was calculated. For bound phenolic compounds, the meal from the previous step was mixed with NaOH (4 M, 20 mL) and stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The sample was centrifuged again (20 min, 5000 rpm), and the supernatant was collected. Its pH was adjusted to 4.5–5, then dried, and the yield was determined18.

Total phenol and flavonoid contents and antioxidant activity

Total phenol and flavonoid contents of both free and bound phenolic extracts were measured using the Folin-Ciocalteu and aluminum chloride colorimetric methods. The results were expressed as mg of gallic acid per gram of meal (mg GAL/g meal) and mg of quercetin per gram of meal (mg QE/g meal), respectively19,20. Antioxidant activity was measured using the DPPH method, and the IC50 value was calculated21.

Phenolic compound analysis

The separation and identification of phenolic acids were carried out using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) (Knauer, Berlin, Germany). A 20 µL extract sample (1 mg/mL) was injected into a reverse-phase Welch Ultisil XB-C18 column (150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size). The mobile phases consisted of solvent A (methanol) and solvent B (water, acidified with 0.1% formic acid). Initially, the ratio of solvent A to solvent B was 30:70 (v/v), which gradually increased to 100% solvent A over 38 min, followed by a 7-min hold at 100% solvent A. The flow rate was set to 0.5 mL/min, and detection was performed at 280 nm. A 20 µL sample with a concentration of 500 ppm was injected into the HPLC system. The total analysis time for each sample was 45 min22. Phenolic compounds were identified by comparing the retention times of each peak with those of standard compounds. Quantification of the phenolic acids was based on multilevel external calibration curves. Also, the method validation of studied phenolic compounds and calibration curves are shown at Table 2.

Carbohydrate and protein assay

The phenol-sulfuric acid method was used to measure total sugar concentration using glucose as a standard. Absorbance was measured at 485 nm23. Protein content was calculated from nitrogen content, which was determined by the Kjeldahl method, using a specific conversion factor24. The protein content was calculated from nitrogen content, which was determined by the Kjeldahl method, using the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 6.2524.

Mineral content and ash analysis

Nitrogen content was determined using the Kjeldahl method as described by Magomya et al.24. The wet digestion method was used for sample digestion prior to mineral analysis. Briefly, 4 mL of nitric acid was added to the sample (1.0 g), which placed in a 100 mL volumetric flask. The sample was heated on a water bath, until the fumes subside. After cooling, an additional 4 mL of perchloric acid was added, followed by further heating until a small volume remains. Finally, the solution was filtered and diluted to the final volume (100 mL) with distilled water. Calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) concentrations were measured by digestion followed by analysis with an atomic absorption spectrophotometer, as described by Udoh25. Potassium (K) content was determined using a flame photometer, with calibration based on a potassium standard curve26. Ash content was determined by heating the sample at 550 °C for 3.5 h in a muffle furnace and weighing the residue27.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 software and data were compared using one-way ANOVA. The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with three replications. Assumptions for ANOVA were checked using PROC UNIVARIATE, and since residuals were normally distributed, no data transformation was needed. Tukey’s test was applied to identify significant differences between treatments at a significance level of P < 0.05. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess correlations between traits, while cluster analysis was conducted using the UPGMA method and Euclidean squared distance. Oilseeds were grouped the based on standardized mean trait data, and the clusters were compared using a completely randomized design.

Results

Meal residual oil contents and DPPH free radical scavenging capacities

Figure 1a illustrates the residual oil content of the oilseed meals. The study revealed significant differences in both the residual oil content and the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of the oils. Based on the results, Sesamum indicum, Brassica napus, and Nigella sativa meals exhibited the highest residual oil contents. Additionally, Arachis hypogaea and Brassica napus oils showed the highest ability to inhibit DPPH free radicals compared to other oils (Fig. 1b), indicating their strong antioxidant properties.

Total phenol, flavonoid contents, and antioxidant activities

Figure 2a shows the yields of free and bound phenolic extracts obtained from oilseed meals. Significant differences in total phenol, flavonoid contents, and antioxidant activities were observed between meals. According to Fig. 2a, the highest yields were obtained from B. napus, Prunus armeniaca, and Helianthus annuus meals, while Cucurbita pepo meal had the lowest content of phenolic compounds.

(a) Yields, b) total phenolic content, c) total flavonoid content, and d) antioxidant activities of the free and bound phenolic extracts obtained from oilseed meals. Different uppercase letters in columns of the same area indicate a statistical difference in free phenolic compounds between oilseed meals according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different lowercase letters in columns of same area indicate a statistical difference in bound phenolic compounds among oilseed meals according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 2b illustrates the total phenolic content of free and bound phenolic extracts. The highest total phenolic content in free phenolic extracts was found in Pistacia atlantica, followed by H. annuus and Lepidium royleana. Regarding the bound phenolic extracts, the highest total phenolic content was also observed in P. atlantica, followed by H. annuus and L. royleana. Figure 2c presents the flavonoid content of the extracts. The highest flavonoid content in free phenolic extracts was recorded in P. atlantica, followed by L. royleana, H. annuus, and N. sativa. Among the bound phenolic extracts, the highest flavonoid content was found in P. atlantica, followed by H. annuus, N. sativa, and L. royleana.

The DPPH radical scavenging activities of the samples were evaluated and showed a concentration dependent increase in radical scavenging properties. The IC50 values of the extracts are displayed in Fig. 2d. Among the free phenolic extracts, P. atlantica had the highest radical scavenging potency with the lowest IC50 value, followed by H. annuus, L. royleana, and Coreopsis tinctoria. These values were compared with the IC50 value of standard ascorbic acid (33.60 ± 1.01 µg/mL). The IC50 values of the bound phenolic extracts from H. annuus, L. royleana, C. tinctorius, and P. atlantica meals were 139.53 ± 7.21, 265.2 ± 15.49, 271.35 ± 12.81, and 467.83 ± 47.63 µg/mL, respectively, indicating weaker antioxidant properties compared with ascorbic acid.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of phenolic compounds in meals

The qualitative and quantitative analysis of the phenolic compounds in the free phenolic extracts is presented in Table 3. The greatest diversity of phenolic compounds was observed in the free phenolic extract of L. royleana meal, while the lowest variety was found in the free phenolic extracts of P. glabra, (A) hypogaea, and C. pepo (Fig. 3). At a level of p < 0.05, H. annuus and L. royleana meals showed the highest amounts of rosmarinic acid, respectively. The highest amount of para-coumaric acid was significantly recorded in L. royleana extract, followed by (B) napus (p < 0.05). Additionally, P. atlantica meal extract contained the highest amounts of quercetin, gallic acid, and cinnamic acid, respectively (Fig. 3).

Chromatogram of free phenolic extracts obtained from oilseed meals; 1: hesperidin; 2: gallic acid; 3: protocatechuic acid; 4: rutin; 5: rosemarinic acid; 6: para-hydroxybenzoic acid; 7: vanillic acid; 8: caffeic acid; 9: para-coumaric acid; 10: ferulic acid; 11: meta-coumaric acid; 12: salicylic acid; 13: cinnamic acid; and 14: quercetin.

The analysis of the bound phenolic extracts is presented in Table 4. At a level of p < 0.05, the highest concentrations of para-hydroxybenzoic acid, para-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and meta-coumaric acid were found in the bound phenolic extracts from B. napus meal. In L. royleana meal extracts, gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, rosmarinic acid, and caffeic acid were the predominant phenolic compounds, whereas P. atlantica meal extracts contained significant amounts of gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, meta-coumaric acid, and cinnamic acid. P. atlantica meals also had the highest cinnamic acid content (p < 0.05). No phenolic compounds were detected in the extracts of Cannabis sativa, A. hypogaea, S. indicum, Linum usitatissimum, and H. annuus.

Proteins and soluble carbohydrates in meals

The protein and carbohydrate contents of the meals are shown in Fig. 4. The results showed significant differences in the protein and soluble carbohydrate contents of oilseed meals. At a level of p < 0.05, the highest amount of carbohydrates was recorded for Arachis hypogaea, followed by Brassica napus, and Helianthus annuus. Therefore, these three meals can be considered rich sources of carbohydrates. The highest protein contents were significantly found in H. annuus, Lepidium royleana, Cucurbita pepo, and Sesamum indicum meals (p < 0.05).

The protein and carbohydrate content of the meals. Different capital letters in columns of the same area indicate a statistical difference in protein content between oilseed meals according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different lower-case letters in columns of the same area indicate a statistical difference in carbohydrate content between oilseed meals according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Amount of ash and mineral compounds

The ash and mineral contents of the oilseed meals are presented in Table 5. The study revealed significant differences in the ash and mineral contents of the meals. At a level of p < 0.05, the highest concentration of nitrogen was found in H. annuus, followed by L. royleana, C. pepo, and S. indicum. Among the meals analyzed, the highest potassium content was significantly recorded in Prunus armeniaca, H. annuus, and A. hypogaea (p < 0.05). The findings showed that H. annuus, C. pepo, and Cannabis sativa meals had significantly the highest phosphorus content. The maximum calcium content was observed in Coreopsis tinctoria seed meal. The highest levels of magnesium were significantly associated with C. pepo and L. royleana meals. Analysis of residual ash showed that C. tinctorius, Portulaca oleracea, and Pistacia atlantica meals had the lowest ash content at a level of p < 0.05.

Cluster analysis results

Figure 5 shows the cluster analysis of the samples. The 15 oilseed species were divided into three groups. The cluster analysis revealed that C. pepo, C. tinctorius, L. royleana, B. napus, H. annuus, C. sativa, N. sativa, P. oleracea, A. hypogaea, and P. armeniaca belong to group A. S. indicum is in group B, while other meals such as Linum usitatissimum, P. atlantica, C. tinctoria, and P. glabra belong to group C.

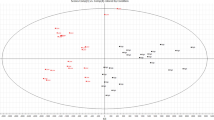

Principal component analysis (PCA)

The results of the PCA showed that five components had eigenvalues greater than one and were recognized as significant components (Fig. 6). The first and second components had the highest relative variance of 34.42% and 26.70%, respectively, accounting for 61.12% of the total variance (Fig. 7). The biplot diagram showed that H. annuus, B. napus, P. armeniaca, A. hypogaea, and L. royleana had the most similarities based on the dominant traits and were grouped together, correlating with traits Y11, Y9, Y12, Y10, and Y14 traits. Conversely, C. pepo, P. oleracea, C. sativa, and S. indicum were grouped together and showed a strong relationship with traits Y16 and Y17 traits. The PCA results indicated that N. sativa and P. atlantica had a strong correlation with Y1, Y5, Y13, Y2, Y3, Y6, and Y7 traits. Additionally, P. glabra, L. usitatissimum, C. tinctoria, and C. tinctorius were placed in a group with strong correlations with Y4, Y8, and Y15 traits. The scree plot displayed in Fig. 8 confirmed the importance of the first two components, each with eigenvalues greater than one, indicating their significance. The specific values for the first and second components were 34.42% and 26.70%, respectively.

Biplot derived based on first and second principal components (PC) in different traits. Y1: yield (free phenolic compounds); Y2: total phenol (free); Y3: total flavonoid (free); Y4: antioxidant activity (IC50, free); Y5: yield (bound phenolic compounds); Y6: total phenol (bound); Y7: total flavonoid (bound); Y8: antioxidant activity (IC50, bound); Y9: HD (free); Y10: protein; Y11: carbohydrate; Y12: nitrogen content; Y13: potassium content; Y14: phosphorus content; Y15: calcium content; Y16: magnesium content; Y17: ash content.

Discussion

Meal residual oil content

During the consumption cycle of oilseed meals, significant amounts of oil are lost. A significant proportion of the annual budget is spent on importing oilseeds or vegetable oils, with a high percentage of oil being imported. This underscores the necessity of maximizing the extraction of oils from these meals. By extracting the remaining oils, they can be reintegrated into the consumption cycle. In this study, the most oil was extracted from S. indicum, B. napus, and N. sativa meals. Additionally, B. napus and H. annuus oils exhibited superior inhibition of DPPH free radicals compared to other oils. Thus, the re-extraction of oils from N. sativa, B. napus, and S. indicum meals is of significant value to the food, cosmetic, and biofuel industries, which are of growing importance. This re-extraction process would also increase the economic value of these meals.

Bioactive compounds

Phenolic compounds, which are metabolites found in a variety of fruits, vegetables, and medicinal plants, have numerous biological properties and offer high nutritional value28,29. Identifying these compounds from affordable and readily available sources is valuable, and oilseed meals are one such source. These compounds in oilseed meals can be used as natural antioxidants in the food, pharmaceutical, and health industries. Our study showed that the highest levels of phenolic and flavonoid compounds were found in the meals of P. atlantica, H. annuus, and L. royleana. Additionally, the antioxidant properties of these meals were remarkable, with extracts of P. atlantica, H. annuus, L. royleana, and C. tinctoria showing the strongest antioxidant effects. Among these, P. atlantica meal extract showed antioxidant properties comparable to those of ascorbic acid.

Furthermore, a positive correlation between phenolic content and antioxidant activity was confirmed, in line with previous findings, where phenolic compound levels directly were correlated with antioxidant properties16,30. Studies on the metabolites and antioxidant activities of P. atlantica and H. annuus seeds support these findings. Peksel et al.31 demonstrated the potent antioxidant properties of P. atlantica and attributing this to its constituents, including total phenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins. An analysis of the phenolic profile of P. atlantica hulls showed ferulic acid, quercetin, and naringenin as the main phenolic compounds, supporting its potential as an antioxidant agent in the pharmaceutical and food industries32. Similarly, Karamać et al.33 analyzed the antioxidant capacity of crude extracts of H. annuus phenolic compounds and found results comparable to synthetic antioxidants. Another study concluded that the antioxidant capacity of H. annuus was largely due to its caffeic acid derivatives34.

Thus, our findings demonstrate a direct correlation between the potent antioxidant activity of P. atlantica and H. annuus meals and their unique phenolic profiles. Through comprehensive HPLC analysis, we identified quercetin as the dominant phytochemical in P. atlantica meal extracts, representing a remarkable 15% of the total extract. Also, our results revealed that H. annuus meal extract demonstrates remarkable antioxidant properties, ranking second in potency among all tested oilseed meals. The most significant discovery is its exceptionally high concentration of rosmarinic acid, accounting for over 17% of the total phenolic content (Table 3). So, H. annuus meal is as a rich source of rosmarinic acid, which is unusual since this compound is typically associated with herbs like rosemary, not oilseeds.

These two compounds (quercetin and rosmarinic acid) are found in various foods and plants. Quercetin has been shown to prevent numerous diseases, including osteoporosis, certain cancers, tumours, lung disorders, and cardiovascular problems. Its potent antioxidant properties have been linked to its effects on glutathione, enzyme activity, signal transduction pathways and reactive oxygen species35,36.

Rosmarinic acid, an ester of caffeic acid, has numerous biological properties, including antimicrobial, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-depressant, and anti-aging effects. It has strong antioxidant activity and is used as a food pigment to prevent oxidation and improve storage stability in the food industry37,38. Based on previous studies and our findings, we conclude that P. atlantica and H. annuus meal extracts have high antioxidant properties, mainly due to the presence of quercetin and rosmarinic acid, respectively.

Many studies have shown that lipid oxidation during food processing produces potentially toxic products that can adversely affect food quality and pose health risks39. There are several methods to enhance food stability, delay oxidation, and prevent the formation of undesirable components, including the use of synthetic antioxidants40. However, growing concerns about the safety of synthetic antioxidants have led to increased interest in natural polyphenols, such as quercetin and rosmarinic acid. Our results indicate that P. atlantica and H. annuus meals, which are rich in quercetin and rosmarinic acid, respectively, are excellent sources of natural antioxidants for the food industry.

So, the quercetin-rich nature of P. atlantica meal, coupled with its synergistic phytochemical matrix, positions this agricultural byproduct as a superior candidate for functional food formulations, nutraceutical applications, and clean-label preservative systems. This discovery represents a significant advancement in natural antioxidant research, offering both scientific and commercial implications for sustainable resource utilization. Also, H. annuus meal as a rich source of rosmarinic acid fundamentally expands our understanding of rosmarinic acid distribution in plants and opens new possibilities for sustainable production of this pharmaceutically important compound. The discovery is particularly valuable for regions with large sunflower oil production, offering local opportunities for value-added product development from agricultural byproducts.

Nutrition values

Although many oilseeds are primarily used for animal feed or organic fertilizers, they are inexpensive and readily available food sources, rich in a variety of nutrients and possessing significant nutritional potential. Therefore, an important research focus is the study of nutrients in oilseed meals, particularly those consumed in large quantities. This could lead to the development of processed foods with significant health benefits for humans.

Carbohydrates play a crucial role in human health, performing various vital functions in the body41. Our findings show that the meals of (A) hypogaea, (B) napus, and H. annuus seed meals are excellent sources of carbohydrates. Proteins, another essential nutrient, are crucial in the daily diet for the production of hormones, enzymes, and antibodies that support key physiological functions42,43. In this study, H. annuus seed meal was found to have the highest protein content, making it a rich source of both protein and carbohydrate. As such, H. annuus meal could be used to produce dietary, sports, and pharmaceutical supplements.

Ash content, an important factor in the proximate analysis for nutritional evaluation, is a quality attribute for certain food ingredients. Our results indicate that C. tinctorius seed meal had the lowest ash content, suggesting that it has a high nutritional value. A study by Laghari et al.44 supports our findings by showing that H. annuus seed meal is rich in essential minerals such as phosphorus, calcium, potassium, magnesium, zinc, iron, manganese, selenium, and copper. These results are consistent with the findings of the present study.

Our research has uncovered notable variations in mineral composition among different oilseed meals, with particularly interesting findings regarding their potassium and calcium content. The P. armeniaca seed meal emerged as a standout source of potassium, along with H. annuus and A. hypogaea meals, all exhibiting substantially higher potassium levels compared to other samples studied. This elevated potassium concentration suggests these agricultural byproducts could serve as valuable ingredients for developing natural mineral supplements, especially beneficial for individuals needing to maintain electrolyte balance or support cardiovascular health. The presence of such high mineral content in what is typically considered waste material presents an exciting opportunity for creating value-added products from existing agricultural processes. Also, our discovery was equally significant regarding calcium levels in C. tinctorius seed meal, which demonstrated an exceptionally high calcium concentration of 16.2%. These finding positions safflower meal as a particularly promising candidate for bone health supplements and calcium-fortified food products. The affordability and widespread availability of this byproduct make it especially attractive for nutritional applications in both developed and developing regions. However, our analysis revealed that this same C. tinctorius meal contained comparatively lower amounts of phosphorus and magnesium, suggesting that while it excels as a calcium source, it may need to be combined with other mineral-rich ingredients to create a fully balanced nutritional supplement. Moreover, these findings collectively highlight the untapped potential of oilseed meals as sustainable sources of essential minerals. The variation in mineral profiles across different meal types presents an advantage, as it allows for strategic formulation of blended products that can deliver comprehensive mineral supplementation. For instance, combining calcium-rich safflower meal with potassium-abundant sunflower or apricot seed meal could yield nutritionally balanced functional foods or supplements. This approach not only maximizes the nutritional value of agricultural byproducts but also contributes to a more circular and sustainable food system by transforming waste streams into valuable health-promoting ingredients. In addition, the implications of these discoveries extend beyond basic nutrition, potentially influencing how we view and utilize agricultural processing byproducts globally. Future research should focus on optimizing extraction methods to preserve mineral bioavailability, assessing potential interactions with other meal components, and evaluating the practical application of these mineral-rich meals in various food matrices. Additionally, studies examining the effects of different processing techniques on mineral stability and bioavailability would further enhance our ability to harness the full nutritional potential of these underutilized resources. This line of investigation could ultimately lead to the development of innovative, sustainable, and cost-effective solutions for addressing mineral deficiencies in diverse populations worldwide.

Dendrogram from cluster analysis

A dendrogram resulting from cluster analysis facilitates the study of differences and similarities between oilseed meals. The resulting groupings are useful for selecting meals based on desired characteristics. Each group consists of meals with similar characteristics, which helps in selecting meals for extracting and utilizing key compounds. By analyzing the diversity between the groups, the industry can achieve the desired composition for various applications, given that most oilseeds contain valuable compounds.

In industrial projects, it is crucial to select plant samples with specific compositions that correlate highly with biological properties such as antioxidant activity is crucial. These correlations are used as indirect selection criteria. In the present study, the relationships between different characteristics and their effects on antioxidant performance in oilseed meals were investigated to better understand how these traits influence each other. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess these relationships.

The correlation results showed remarkable associations between C. pepo, S. indicum, A. hypogaea, P. armeniaca, and L. usitatissimum. Additionally, N. sativa, P. oleracea, and P. glabra exhibited correlations with each other, as well as with several other samples. The results also showed that the content and quality of phenols and flavonoids, especially phenolic compounds, in these samples correlated directly with their antioxidant activity.

Conclusion

The present study evaluated and compared the residual oil content, total phenol and flavonoid content, phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, residual ash, carbohydrates, proteins, and various nutritional elements in high consumption oilseed meals. Based on the data, Pistacia atlantica meal had the highest phenolic and flavonoid contents (17.67 ± 0.69 mg GAL/g meal and 3.073 ± 0.003 mg QE/g meal, respectively) and exhibited the strongest DPPH radical scavenging activity (IC50 = 33.11 ± 1.41 µg/mL). HPLC analysis revealed that P. atlantica and Helianthus annuus meals were particularly rich in quercetin (37.20 ± 2.97 mg/g meal) and rosmarinic acid (46.67 ± 3.32 mg/g meal), respectively, suggesting that the high antioxidant properties of these meals are probably due to the presence of these compounds. The highest carbohydrate content was observed in Arachis hypogaea (37.92 ± 0.11%), while H. annuus had the highest protein content (45.12 ± 1.83%). Mineral analysis revealed that Prunus armeniaca, H. annuus, and Carthamus tinctoria meals contained the highest levels of potassium (1.73 ± 0.04%), phosphorus (0.60 ± 0.03%), and calcium (16.20 ± 0.09%), respectively. Furthermore, Cucurbita pepo and Lallemantia royleana meals had the highest magnesium content. Given the nutrient profiles and active compounds of these meals, especially P. atlantica, H. annuus, and L. royleana, it can be concluded that they have significant potential in the food, medicinal, and health industries. In conclusion, these oilseed meals, especially P. atlantica, H. annuus, and L. royleana, are rich in valuable bioactive compounds, making them highly applicable across various sectors, including medicine, nutrition, industry, energy production, agriculture, across, cosmetics, and economic development.

This study of the nutritional and bioactive potential of oilseed meals has some limitations. It focuses solely on cold-pressed extraction methods and covers only a limited variety of species. There is a lack of in vivo bioavailability studies and functional property evaluations are absent. Future research should optimise extraction techniques, investigate the stability of bioactive compounds, comprehensively characterise residual oils from a physicochemical perspective, assess the synergistic effects in functional foods, and perform economic feasibility studies. Addressing these gaps would enhance the practical application of oilseed meals in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Matwijczuk, A., Zając, G., Kowalski, R., Kachel-Jakubowska, M. & Gagoś, M. Spectroscopic studies of the quality of fatty acid Methyl esters derived from waste cooking oil. Pol. J. Envir Stud. 26 (6), 2643–2650 (2017).

Babu, S. et al. Exploring agricultural waste biomass for energy, food and feed production and pollution mitigation: a review. Biores Technol. 360, 127566 (2022).

Ravindran, R. & Jaiswal, A. K. Exploitation of food industry waste for high-value products. Trend Biotechnol. 34 (1), 58–69 (2016).

Usman, I. et al. Innovative applications and therapeutic potential of oilseeds and their by-products: an eco‐friendly and sustainable approach. Food Sci. Nut. 11 (6), 2599–2609 (2023).

Hassanien, M. F. R. Bioactive Phytochemicals from Vegetable Oil and Oilseed Processing by-products (Springer Nature, 2023).

Gupta, A., Sharma, R., Sharma, S. & Singh, B. Oilseed as potential functional food Ingredient. In (eds. Kumar, P. et al.) Trends & Prospects in Food Technology, Processing and Preservation 25–58 (2018).

Nevara, G. A. et al. Oilseed meals into foods: an approach for the valorization of oilseed by-products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nut. 2022, 1–14 (2022).

Canesin, E. A., de Oliveira, C. C., Matsushita, M., Dias, L. F. & Pedrao, M. R. De souza, N.E. Characterization of residual oils for biodiesel production. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 17 (1), 39–45 (2014).

Morris, A. L. & Mohiuddin, S. S. Biochemistry nutrients. In StatPearls [Internet] (StatPearls Publishing, 2021).

Petropoulos, S. A. et al. Seed oil and seed oil byproducts of common purslane (Portulaca Oleracea L.): a new insight to plant-based sources rich in omega-3 fatty acids. LWT -Food Sci. Technol. 123, 109099 (2020).

Vasudha, C. & Sarla, L. Nutritional quality analysis of sunflower seed cake (SSC). J. Pharm. Innovat. 10, 720–728 (2021).

Mansouri, F. et al. Proximate composition, amino acid profile, carbohydrate and mineral content of seed meals from four safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) varieties grown in north-eastern Morocco. Oilseed Fat. Crop Lip. 25 (2), A202 (2018).

Delgado, A. M., Issaoui, M. & Chammem, N. Analysis of main and healthy phenolic compounds in foods. J. AOAC Inter. 102 (5), 1356–1364 (2019).

Ofori-Boateng, C. & Lee, K. T. Sustainable utilization of oil palm wastes for bioactive phytochemicals for the benefit of the oil palm and nutraceutical industries. Phytochem Rev. 12 (1), 173–190 (2013).

Pojić, M. et al. Characterization of byproducts originating from hemp oil processing. J. Agricul Food Chem. 62 (51), 12436–12442 (2014).

Siger, A., Czubinski, J., Dwiecki, K., Kachlicki, P. & Nogala-Kalucka, M. Identification and antioxidant activity of sinapic acid derivatives in Brassica napus L. seed meal extracts. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 115 (10), 1130–1138 (2013).

Hashempour, H. et al. Fatty acid composition analysis of aerial parts of selected Salvia species growing in Iran and chemotaxonomic approach by shoot fatty acid composition. Anal. Bioanal Chem. Res. 5 (2), 297–306 (2018).

Kotásková, E., Sumczynski, D., Mlček, J. & Valášek, P. Determination of free and bound phenolics using HPLC-DAD, antioxidant activity and in vitro digestibility of Eragrostis tef. J. Food Compos. Anal. 46, 15–21 (2016).

Ebadi, M., Ahmadi, F., Tahmouresi, H., Pazhang, M. & Mollaei, S. Investigation the biological activities and the metabolite profiles of endophytic fungi isolated from Gundelia tournefortii L. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 6810 (2024).

Babaei Rad, S., Mumivand, H., Mollaei, S. & Khadivi, A. Effect of drying methods on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Capparis spinosa L. fruits. BMC Plant. Biol. 25 (1), 133 (2025).

Dehghanian, Z., Ahmadabadi, M. & Mollaei, S. Impressive arrays of morphophysiological and biochemical diversity of pomegranates in arasbaran; a hidden pomegranate paradise. Gen. Res. Crop Evol. 71 (8), 5079–5093 (2024).

Babaei-Rad, S., Mumivand, H., Mollaei, S., Khadivi, A. & Postharvest, U. V. B. UV-C treatments combined with fermentation enhance the quality characteristics of Capparis spinosa L. fruit, improving total phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, phenolic acids, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 483, 144306 (2025).

Dubois, M., Gilles, K. A., Hamilton, J. K., Rebers, P. A. & Smith, F. A colorimetric method for the determination of sugars. Nature 168 (4265), 167–167 (1951).

Magomya, A. M., Kubmarawa, D., Ndahi, J. A. & Yebpella, G. G. Determination of plant proteins via the Kjeldahl method and amino acid analysis: A comparative study. Inter J. Sci. Technol. Res. 3 (4), 68–72 (2014).

Udoh, A. P. Atomic absorption spectrometric determination of calcium and other metallic elements in some animal protein sources. Talanta 52 (4), 749–754 (2000).

Mason, J. L. Flame photometric determination of potassium in unashed plant leaves. Anal. Chem. 35 (7), 874–875 (1963).

Park, Y. W. & Bell, L. N. Determination of Moisture and Ash Contents of Foods. (eds. Nollet, M. L.) 59–92 (Marcel Dekker, Inc., 2004).

Zhang, Y., Cai, P., Cheng, G. & Zhang, Y. A brief review of phenolic compounds identified from plants: their extraction, analysis, and biological activity. Nat. Prod. Communicat. 17 (1), 1934578X211069721 (2022).

Rathod, N. B. et al. Recent developments in polyphenol applications on human health: a review with current knowledge. Plants 12 (6), 1217 (2023).

Shi, L., Zhao, W., Yang, Z., Subbiah, V. & Suleria, H. A. R. Extraction and characterization of phenolic compounds and their potential antioxidant activities. Envir Sci. Pollution Res. 29 (54), 81112–81129 (2022).

Peksel, A., Arisan-Atac, I. N. C. I. & Yanardag, R. Evaluation of antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of the extracts of Pistacia atlantica desf. Leaves. J. Food Biochem. 34 (3), 451–476 (2010).

Nachvak, S. M., Hosseini, S., Nili-Ahmadabadi, A., Dastan, D. & Rezaei, M. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Pistacia atlantica subsp. Kurdica from Awraman. J. Rep. Pharm. Sci. 7 (3), 222–230 (2018).

Karamać, M., Kosińska, A., Estrella, I., Hernández, T. & Dueñas, M. Antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds identified in sunflower seeds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 235 (2), 221 (2012).

Amakura, Y., Yoshimura, M., Yamakami, S. & Yoshida, T. Isolation of phenolic constituents and characterization of antioxidant markers from sunflower (Helianthus annuus) seed extract. Phytochem Lett. 6 (2), 302–305 (2013).

Qi, W., Qi, W., Xiong, D. & Long, M. Quercetin Its antioxidant mechanism, antibacterial properties and potential application in prevention and control of toxipathy. Molecules 27 (19), 6545 (2022).

Zhang, X., Tang, Y., Lu, G. & Gu, J. Pharmacological activity of flavonoid Quercetin and its therapeutic potential in testicular injury. Nutrients 15 (9), 2231 (2023).

Noor, S. et al. Biomedical features and therapeutic potential of Rosmarinic acid. Archives Pharm. Res. 45 (4), 205–228 (2022).

Kernou, O. N., Azzouz, Z., Madani, K. & Rijo, P. Application of Rosmarinic acid with its derivatives in the treatment of microbial pathogens. Molecules 28 (10), 4243 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Comparison between synthetic and rosemary-based antioxidants for the deep frying of French Fries in refined soybean oils evaluated by chemical and non-destructive rapid methods. Food Chem. 335, 127638 (2021).

Wang, D., Xiao, H., Lyu, X., Chen, H. & Wei, F. Lipid oxidation in food science and nutritional health: a comprehensive review. Oil Crop Sci. 8 (1), 35–44 (2023).

BeMiller, J. N. 17-Carbohydrate nutrition, dietary fiber, bulking agents, and fat mimetics. In Carbohydrate Chemistry for Food Scientists 323–350 (2019).

Wolfe, R. R. The role of dietary protein in optimizing muscle mass, function and health outcomes in older individuals. Br. J. Nut. 108 (S2), S88–S93 (2012).

Watford, M., Wu, G. Protein. Adv. Nut. 9 (5), 651 (2018).

Laghari, A. H., Memon, S., Nelofar, A., Khan, K. M. & Yasmin, A. Determination of free phenolic acids and antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts obtained from fruits and leaves of Chenopodium album. Food Chem. 126 (4), 1850–1855 (2011).

Price, C. T., Langford, J. R. & Liporace, F. A. Essential nutrients for bone health and a review of their availability in the average North American diet. Open. Orthopaed J. 6, 143 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University.

Funding

We thank from Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University for funding support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mollaei, S., Hosseini-Nami, S.M. & Hazrati, S. Evaluation of the nutritional value and active compounds of commercial and non-commercial oilseed meals. Sci Rep 15, 25043 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10671-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10671-1