Abstract

Local extinction of milky stork Mycteria cinerea has been reported from the wild of Thailand. Only one captive population exists at Nakhon Ratchasima Zoo and is currently maintained as a breeding stock of the country. To initiate future reintroduction program, determination of genetic diversity in this captive population is crucial for its long-term sustainability in nature. The present study employed a combination of maternally inherited mitochondrial control region and biparentally inherited nuclear microsatellite markers to evaluate genetic status of these captive individuals. Phylogenetic analysis and haplotype network construction demonstrated moderate haplotype diversity (h = 0.560 ± 0.050) and low nucleotide polymorphism (π = 0.0007 ± 0.0001). Multilocus microsatellite examination further showed low heterozygosity (HO = 0.387; HE = 0.374) with no significant evidence of inbreeding (FIS = -0.036). Moreover, STRUCTURE computation revealed two distinct genetic clusters among all studied individuals. Cluster 1 carried all three identified haplotypes and exhibited relatively higher genetic diversity than the cluster 2. Significant inbreeding was not observed in these two clusters. Assessment of pairwise relatedness additionally indicated that a majority of sample pairs were not genealogically related, thereby providing potential candidates for future breeding. Finally, suitable stork individuals and criteria for the effective selection of breeding pairs are proposed. Our research not only reports comprehensive genetic data of the sole remaining population of Thai milky stork for the first time, but also proposes a practical strategic framework by utilizing the obtained genetic information along with judicious breeding selection for recovering this endangered species of Thailand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wetlands are unique ecosystems known for their rich and distinct nature where a diverse array of terrestrial and aquatic fauna dwell in1. However, many wetland habitats are currently degrading worldwide due to ecological factors themselves and pressing anthropogenic activities1,2,3. Such loss is considered a significant threat that leads to rapid population declines, fragmentation, or potential local extinction in numerous species of wetland-inhabiting creatures, including wading birds4,5,6,7. Conservation strategies focused solely on habitat preservation and restoration may prove inadequate for revitalizing natural populations of endangered species that continue to diminish and exhibit reducing population sizes. The introduction of captive-bred individuals into the wild has alternative potential to enhance population recovery and should be executed in conjunction with in situ conservation efforts to ensure the long-term viability of the dwindling species8,9,10.

For successful reintroduction, efforts should prioritize on releasing genetically unrelated captive-bred founders with sufficient genetic variation to sustain population genetic diversity and facilitate the establishment of self-sustaining wild populations11,12,13. However, captive breeding programs often commence with a limited number of founders, making them inevitably more vulnerable to genetic diversity loss owing to inbreeding and genetic stochasticity, such as genetic drift. This could severely diminish adaptive potential of reintroduced populations and undeniably increase their risk of extinction14,15. Hence, breeding programs must be properly managed and wisely organized in the way that the released population will propagate genetically, biologically, and ecologically. Prior to initiating further breeding and reintroduction initiatives, it is a prerequisite to determine genetic diversity and inbreeding levels of existing captive populations, especially those of endangered ones.

Milky stork (Mycteria cinerea, Ciconiidae, Ciconiiformes) is a large piscivorous wading bird that serves as an important bioindicator and a flagship vertebrate of tropical wetland ecosystems16. This avian species has been used as a monitor to assess food source abundance, detect environmental pollution, and evaluate wetland conversion16,17. However, since 1980, global populations of milky storks have been sharply declining throughout their ranges in Southeast Asia, due primarily to intense hunting pressure, targeting eggs and nestlings, as well as loss of suitable breeding and nesting habitats18,19,20. As a result, the species was classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List in 201321 and the remaining wild populations (estimated approximately at 600–1,850 mature individuals) are primarily located in Cambodia, Malaysia, and Indonesia, with Sumatra recognized as the global stronghold22,23,24.

In Thailand, milky stork is designated as critically endangered by the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP)25and is classified as protected wild animal under the Wild Animal Conservation and Protection Act, B.E. 2562 (2019). This stork was historically found in the south, but it is presumed to be extirpated from its natural habitats in the past few decades, and no nesting sites have been reported24,26,27. Although a small number of milky storks (≤ 10 individuals) have been sporadically observed in the wild of Thailand, such as at the Pak Thale area (Phetchaburi Province), Huai Talat Reservoir Non-hunting Area (Buriram Province),28 and Huai Chorakhe Mak Reservoir Non-hunting Area (Buriram Province), these birds are non-breeding visitors that occasionally migrate to Thailand during the winter period (around December) and probably come from the Prek Toal colony in neighboring Cambodia24,29. Given its significant attribute as a wetland indicator mentioned above, conservation and restoration of this bird in Thailand would not only fulfill its original ecosystems, but also increase avian biodiversity in the wild habitats of the country.

A captive breeding program for conservation of milky stork in Thailand was established in 2008 at Dusit Zoo (DZ) in Bangkok, following the initial introduction of the species to the zoo in 1998. The founder population comprised 19 birds of unknown provenance. In 2014, 21 individuals were relocated to Nakhon Ratchasima Zoo (NRZ) in Nakhon Ratchasima Province. However, it was later found that three of them were hybrids with painted storks30. Despite the NRZ’s active efforts to enhance the survival and population size of milky storks in captivity, which have successfully reached 48 individuals, genetic information regarding this captive population remains limited. Such information is critical, particularly in the absence of studbooks or pedigree records, because it can provide a better understanding of genealogical relationships among individuals within the population, such as parent-offspring or full sibling connections. Consequently, the integration of genetic data into breeding strategies could strengthen breeding efforts and mitigate the elevated risk of inbreeding by promoting appropriate breeding stock selection and avoiding the pairing of closely related individuals12,13,31.

Thus far, existing genetic studies on this bird have primarily concentrated on the adverse effects of introgressive hybridization with closely related species in captivity, which aim to differentiate genetically pure milky storks from hybrids30,32,33. However, comprehensive investigations into the population structure and genetic diversity of genetically pure captive stocks have not been conducted. In this study, we employed a combination of maternally inherited (mitochondrial DNA control region) and biparentally inherited (microsatellite) genetic markers to evaluate the genetic diversity, population structure, and individual genealogical relationships of milky storks at NRZ. Our findings provide valuable insights for the genetic management of this captive population and are essential for the long-term success of breeding and reintroduction programs dedicated to the conservation of the milky stork.

Results

MtDNA haplotype and phylogenetic relationships

A total of 1,200 bp of the mitochondrial control region, excluding the repeat sequences at the 3’ end, was successfully sequenced from 45 stork specimens. The sequences were predominantly A + T (57%), as is characteristic of avian control region segments. No insertion or deletion was observed. Three (0.25%) variable sites were detected from all aligned sequences, defining three distinct haplotypes, namely MCTH1, 2, and 3. The haplotype frequency ranged from 8.9 to 57.8%, with MCTH3 being the most frequent one represented in 26 individuals (Table 1). All genetic diversity indices were shown in Table 2. Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs yielded positive results with no significant difference, suggesting that nucleotide variations were neutrally selected and most likely resulted from random genetic drift. The haplotype (h) and nucleotide (π) diversity indices were 0.560 ± 0.050 and 0.0007 ± 0.0001, respectively, indicating moderate genetic diversity and negligible nucleotide differences in captive population (Table 2).

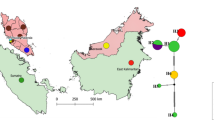

Phylogenetic analyses derived from both Bayesian interference and maximum likelihood approaches showed identical topologies for the relationship among haplotypes and provided monophyletic support for each of them (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1). The minimum spanning haplotype network analysis demonstrated a close genetic relationship among all milky stork haplotypes, with only 1–2 mutational steps between haplotypes (Fig. 1b). The haplotype MCTH2 is located in the center of the three, whereas MCTH1 is connected to haplotypes of other closely related stork species.

(a) Maximum likelihood tree demonstrating phylogenetic relationships among mtDNA haplotypes of 45 captive milky storks based on 1,131 bp of the control region sequences. Numbers at the nodes represent the bootstrap values and posterior probabilities of maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference approaches, respectively. Clades that contain individuals with MCTH1, MCTH2, and MCTH3 haplotypes are shown in pink, blue, and orange, respectively. The scale bar corresponds to 5 substitutions per 100 nucleotide positions. (b) A minimum spanning haplotype network showing the genetic relationship among three unique haplotypes of Thai milky storks. mtDNA haplotypes of other related storks were also included. The size of the circle is proportional to the haplotype frequency. The number in parenthesis represents the mutation steps among haplotypes.

Genotypic sex identification using a molecular approach revealed a total of 22 males and 23 females, with a balanced sex ratio across all samples analyzed (see Supplementary Table S1). These females had three unique haplotypes, with only two storks (MS16♀ and MS39♀) carrying the rare MCTH1 haplotype. All mitochondrial control region sequences from this work have been submitted to the GenBank database under the GenBank accession numbers PV066040–PV066042.

Nuclear genetic diversity, population structure, and genealogical relatedness analyses

All 20 autosomal microsatellite primer pairs used in this study were successfully bound in cross-species amplification for all stork samples; however, five loci (WSµ17, WSµ18, WSµ20, WSµ24, and Cc69) exhibited monomorphic results (see Supplementary Table S2). Following the application of Bonferroni correction to the dataset, no evidence of genotypic linkage disequilibrium (LD) was observed among the 15 polymorphic loci examined, indicating that these loci segregated independently during recombination. Analysis of allele frequencies identified five loci (WSµ23, Cc04, Cc06, Cc10, and Cc37) that significantly deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), with p-value < 0.05 (Table 3). Moreover, four loci exhibited significantly high levels of null allele frequency (NAF) (WSµ23 and Cc06) and/or inbreeding (WSµ23, Cc04, Cc06, and Cc10). Consequently, the loci demonstrating disequilibrium were excluded from further examination, leaving 10 polymorphic loci for subsequent analyses.

The total number of alleles found was 32 and the number of alleles per locus (NA) was relatively low with the mean NA of 3.20 (Table 3). Locus Cc07 was the most polymorphic one with eight alleles while six loci (WSµ13, Cbo108, Cbo109, Cbo151, Cc44, and Cc50) exhibited the lowest level of polymorphism with two alleles per locus. The observed heterozygosity (HO) and expected heterozygosity (HE) ranged from 0.044 in Cc50 to 0.778 in Cc07 and 0.044 in Cc50 to 0.718 in Cc07, respectively, with the mean HO (0.387) slightly higher than the mean HE (0.374). The inbreeding coefficient (FIS) indices ranged from -0.174 in Cbo151 to 0.175 in Cc72 with the overall FIS value of -0.036.

Bayesian genetic clustering analysis using STRUCTURE demonstrated the greatest value of delta K (ΔK) = 164.50, corresponding to K = 2 under 10 simulations for K values ranging from one to ten (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S3). This result is consistent with the identification of the maximum likelihood values (Ln P(K)) = -548.53 at K = 2 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table S4), illustrating that all milky storks can be categorized into two genetic clusters, with 19 and 21 individuals belonging to cluster 1 and cluster 2, respectively (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, five individuals (MS17, MS18, MS23, MS35, and MS44) exhibited genetic admixture between the two clusters (qi < 0.9) (see Supplementary Table S1) and were most likely the progeny of two genetically distinct breeders.

Population structure of 45 milky stork individuals in Nakhon Ratchasima Zoo. (a) StructureSelector’s ΔK and (b) log likelihood (Ln P(K)) graphs indicating that the optimum number of clusters is K = 2. (c) Bayesian genetic clustering STRUCTURE analysis based on 10 microsatellite loci with inferred K = 2 is shown in different colors. Each individual is represented by a vertical bar that illustrates the proportion of the membership coefficient (qi) partitioned into different color segments.

To determine genetic diversity of each cluster, we analyzed genotyping datasets of the two clusters, with and without the admixed individuals, using 10 polymorphic loci. The results showed that cluster-1 samples had higher average allele numbers than the cluster-2 ones. The average observed and expected heterozygosities were also slightly higher in cluster-1 samples although the difference was not statistically significant (HO = 0.421, HE = 0.361 in cluster 1 and HO = 0.375, HE = 0.315 in cluster 2; Fisher’s Exact Test, p > 0.05). Additionally, both clusters exhibited low and negative overall FIS values (Table 4).

The GenAlEx program generated 990 pairwise comparisons from the studied 45 stork individuals, with r values ranging from -0.603 to 1.000 and the mean pairwise r value of -0.023 ± 0.009 (Supplementary Table S5). We categorized the observed r values into four genealogical levels: first-order relative (r = 0.50–1.0), second-order relative (r = 0.25–<0.50), third-order relative (r = 0.125–<0.25), and unrelated (r < 0.125). The results indicated that 72.9% (722 sample pairs) of the individuals examined were not genealogically related and could potentially be used as breeding stocks for subsequent propagation. In addition, 12.2% (121 sample pairs) and 8.7% (86 sample pairs) were classified as second- and third-order relatives, respectively, indicating possible half sibling, aunt, uncle, grandparent, grandchild, niece or nephew relationships. Furthermore, we discovered that 6.2% (61 sample pairs) demonstrated a likely either parent-offspring or full sibling relationships.

Similarly, the ML-Relate program produced r values ranging from 0 to 1, with an average pairwise r value of 0.149 ± 0.215 (Supplementary Table S6). After inferring genealogical relationships, 15.6% (154 sample pairs), 10.7% (106 pairs), and 9.8% (97 pairs) were identified as first-order (r = 0.50–1.0), second-order (r = 0.25–<0.50), and third-order relatives (r = 0.125–<0.25), respectively, while 63.9% (633 sample pairs; r < 0.125) were classified as unrelated. The analyses derived from both programs showed that a pair of MS24♂ and MS34♀ had the highest r value of 1.0.

Discussion

Population recovery initiatives that incorporate captive breeding programs in zoological settings are essential to halt the impending decline of endangered species8,9. Implementation of such programs, underpinned by robust management strategies and comprehensive genetic considerations, holds promise for enhancing future reintroduction efforts and facilitating the long-term viability of reestablished populations12,13,34. In our investigation, we analyzed nearly complete sequences of the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) control region, alongside co-dominant microsatellite markers, to assess genetic diversity, population structure, and individual genetic relatedness within the endangered milky stork for the first time. The findings indicated that the mitochondrial DNA variations aligned with the microsatellite polymorphisms, revealing a concerning limitation in genetic diversity among captive milky storks at the NRZ, demonstrated by both a lack of maternal haplotype variety and reduced autosomal heterozygosity, despite the absence of significant inbreeding.

Variation of mitochondrial DNA in captive milky storks

The control region, recognized for its relatively high molecular evolution rate, is the most variable segment of the avian mitochondrial genome and has become a widely accepted marker for assessing intraspecific variation and phylogenetic relationships across avian species35,36. Structurally, this control region comprises three domains: the hypervariable 5’ domain I, the central conserved domain II, and the hypervariable 3’ domain III37. Our analysis revealed that all observed variations were confined to the hypervariable domain I. However, the limited number of polymorphic sites resulted in low genetic differentiation among haplotypes, as evident in both phylogenetic and haplotype network assessments (Fig. 1).

The mitochondrial control region variations documented in this study were distinct from our previous findings, which indicated no nucleotide substitution in the cytochrome b sequences (1,029 bp) of the same captive population, unifying all stork individuals under a single mtDNA lineage30. This current observation emphasizes the higher mutation rate of the control region and its efficacy as a genetic marker for evaluating intraspecific variability. The primers designed for the control region in this study were based on highly conserved flanking sequences of the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6 (ND6) and the 12S ribosomal RNA genes from several storks and other wading bird mitochondrial genomes. Given the successful amplification of all 45 specimens, the designed primers could also be employed to investigate mtDNA variations in other stork species within the Ciconiidae family and potentially in related non-stork taxa.

The haplotype (h) and nucleotide (π) diversity levels observed in this study were 0.560 and 0.0007, respectively, indicating a moderate haplotype diversity among the captive milky storks. In comparison to previous investigations with the same marker — control region, our captive population displayed lower genetic diversity indices than other related Ciconiidae species, such as the Oriental white stork Ciconia boyciana (h = 0.832, π = 0.0036, n = 237, captive and wild population)36 and the wood stork Mycteria americana (h = 0.822, π = 0.0044, n = 48, wild population)35. Conversely, the milky storks evaluated in our study demonstrated a higher degree of mtDNA diversity in relation to other endangered aquatic birds, such as the crested ibis Nipponia nippon (h = 0.369, π = 0.066, n = 26, captive population)5. Notably, only three distinct haplotypes were identified among the 45 captive storks. This limited haplotype variety likely resulted from founder effects linked to the initial introduction of only a few mtDNA lineages from the founder population. Our findings suggest that at least three female storks with different mtDNA haplotypes should be paired for breeding to conserve maternal lineages in succeeding generations. Furthermore, adopting new lineages by introducing more female individuals with distinct mtDNA haplotypes is critical for enhancing genetic diversity within the existing Thai captive milky stork population, although such a plan must be executed with careful consideration.

Nuclear genetic diversity, population structure, and pairwise relatedness of milky stork in NRZ

Using a cross-species amplification approach, all autosomal microsatellite primers successfully targeted homologous regions within the milky stork genome. Most loci exhibited genotyped allelic sizes that fell within the expected ranges established by the reference species for which the primers were developed (see Supplementary Table S2). However, the majority of microsatellite primers designed for the congeneric wood stork yielded predominantly monomorphic results, in contrast to those developed for the more distantly related species, including the Oriental white stork and the European white stork (Ciconia ciconia). This discrepancy may stem from the original lower allele counts per locus (averaging 2–3 alleles), which contributed to reduced variability in the milky stork. Out of the 20 microsatellite loci analyzed, 15 were identified as polymorphic; however, the observed average number of alleles remained low (Table 3), which corresponded to the limited genetic diversity found. Notably, among the polymorphic loci, Cc04, Cc07, and Cc42 exhibited high polymorphism and may serve as diagnostic molecular markers for both non-invasive sample-based individual identification and assessment of genetic diversity in both captive and wild milky stork populations.

The current study found positive and elevated FIS values, attributed to homozygous excess, resulting in lower observed heterozygosity (HO) compared to expected heterozygosity (HE) at the loci WSµ23, Cc04, Cc06, and Cc10. Furthermore, significant null allele frequencies (NAF) were documented at WSµ23 and Cc06. These findings suggested that the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) deviations seen at these loci could be the result of inbreeding or NAF, while the deviation observed at Cc37 is likely due to other factors, such as small sample size, assortative mating, or mutation38, leading to heterozygosity excess at this locus (HO = 0.844, HE = 0.661) (Table 3). Our analyses with a comparable or smaller set of microsatellite markers [i.e., not the same set of loci as in our study] indicated that milky storks exhibited low levels of heterozygosity (HO = 0.387, HE = 0.374, n = 45, 10 loci) when compared to other stork species from both wild and captive populations, including the European white stork (HO = 0.519, HE = 0.565, n = 213, 11 loci)39, wood stork (HO = 0.400, HE = 0.540, n = 37, 5 loci)40, painted stork Mycteria leucocephala (HO = 0.439, HE = 0.435, n = 32, 3 loci)41, and Asian woolly-necked stork Ciconia episcopus (HO = 0.417, HE = 0.524, n = 86, 13 loci)42. It is noteworthy that low to moderate genetic diversity is a common characteristic among wading birds inhabiting wetland environments, as large-bodied aquatic birds tend to exhibit lower mean heterozygosity levels compared to their terrestrial counterparts43. Additionally, factors, such as historical bottlenecks, could further constrain genetic diversity, as evidenced in a semi-wild population of the European white stork (HO = 0.38, HE = 0.41, n = 30, 13 loci)44. The observed decline in genetic diversity within the captive milky stork population in this study may have been influenced by a founder effect stemming from the limited introduction of genetically diverse individuals, with the population being derived from only 19 founders.

STRUCTURE analysis revealed the presence of two distinct genetic clusters (K = 2) among the examined specimens, indicating that the captive founders of Thai milky storks may have originated from two ancestral populations. Alternatively, if these storks were collected from wild populations, our findings suggested that historical declines and fragmentation in natural populations might have led to the observed subdivision in their nuclear loci. Due to the lack of information regarding the origins, ages, and sexes of the initial stock of milky storks at DZ, it remains uncertain whether the captive individuals possess the same genetic background as the native Thai milky stork. It is likely that DZ acquired these founder individuals as fledglings or juveniles, requiring a significant period before they reached sexual maturity and began reproducing. Furthermore, there are no records indicating that additional milky storks were introduced or reared alongside the original stock at DZ. Therefore, comparisons of genetic data from the NRZ’s milky storks with those from other zoos, such as the Malaysian National Zoo (Zoo Negara), and from wild storks across their habitats, are essential for tracing the origins of captive Thai milky storks. Specifically, an adult male milky stork has been curated in the Zoological Reference Collection at the National University of Singapore. Collected from Satun Province, Thailand, on 19 August 1935, this specimen suggests that this species once inhabited southern Thailand26. Therefore, comparative molecular studies with this preserved specimen are necessary to confirm the genetic background of the current captive milky storks in Thailand.

Storks in two separate STRUCTURE clusters have a male-to-female ratio of about 1:1 (♂ = 10 : ♀ = 9 in cluster 1 and ♂ = 10 : ♀ = 11 in cluster 2). Notably, the majority of cluster-1 individuals (68%: ♂ = 8 and ♀ = 5) possessed the MCTH3 haplotype rather than the MCTH2 (11%: ♂ = 0 and ♀ = 2). In addition, the rare MCTH1 haplotype was found in only four individuals in this cluster but not in cluster 2, whereas the most frequent haplotype detected in cluster 2 was MCTH2 (62%: ♂ = 7 and ♀ = 6). Since cluster-1 samples carried all three haplotypes and exhibited relatively higher genetic diversity than the cluster-2 individuals, the storks in cluster 1 should be prioritized for breeding and conservation efforts.

The absence of significant inbreeding levels in this captive population aligns with pairwise relatedness analyses, demonstrating that a majority of individuals are unrelated. This finding suggested that only a limited number of generations of milky storks have been successfully bred since their relocation to NRZ, thereby reducing the likelihood of inbreeding. The calculated r values obtained from the GenAlEx and ML-Relate programs showed that 61 and 154 of the analyzed sample pairs exhibited close genetic relationships, categorized as the first-order relative, respectively. According to the available records, 21 storks, including three hybrids and three that died prior to sample collection, were transferred to NRZ, suggesting that the 15 surviving genetically pure birds were employed as breeding stocks. These 15 individuals serve as parents for subsequent offspring, giving other 30 storks for this captive population (see Supplementary Table S1). Based on this information, we observed that 33 and 68 first-order relative pairs from either of the two programs had a possible parent-offspring relationship. To ascertain the likelihood of their relationship, the mtDNA haplotypes, molecular sexing, and genotypes (based on Mendel’s laws of inheritance) of these pairs were carefully inspected. Following a meticulous inspection, we found that at least 31 and 57 sample pairs from the GenAlEx and ML-Relate programs, respectively, exhibited such connections. For instance, MS02♀ is identified as the offspring of MS45♀, while MS34♀ is the offspring of MS24♂ (see Supplementary Table S5 and S6 for detailed information). These inferred genealogical relationships may assist zookeepers in mitigating matings among closely related individuals.

Thus, implementing precise management practices that favor coupling between unrelated individuals with distinct genetic profiles is crucial for preventing inbreeding and maintaining genetic diversity in future generations of milky storks12,13,31. Accordingly, the selection of breeding stock for forthcoming generations should be guided by outcomes of sex identification and molecular analyses, encompassing haplotype identity, population structure, and genetic relatedness. On the basis of the results presented in this study, we propose the following criteria for the effective selection of breeding pairs: (i) a male-female sample pair with an r value < 0.125, particularly pairs exhibiting high negative values obtained from the GenAlEx program; (ii) male and female individuals originating from different genetic clusters to preserve genetic diversity; and (iii) female individuals possessing distinct haplotypes to conserve maternal lineages. Potential pairings of breeding stock based on these criteria are provided in Supplementary Table S7.

In this study, clear evidence of inbreeding was not detected although possible close relatedness was found in some pairings of this captive population. This might be due to the limitations of the kinship estimation method or microsatellite marker resolution45,46,47. Further genomic analysis using next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based approaches is required to confirm this phenomenon.

Implications for captive breeding and reintroduction programs

While the NRZ successfully increased the population of milky storks during 2014 to 2018, the limited genetic diversity identified in our study raises significant concerns regarding the fitness and adaptive capacity of these birds to environmental changes, disease challenges, and other threats upon future reintroduction. There is an urgent need to enhance genetic diversity within this confined population to ensure sufficient genetic variation in released individuals. A comprehensive breeding strategy should involve the introduction of new alleles through the acquisition of genetically diverse wild-caught specimens or by facilitating zoo-to-zoo exchanges of captive individuals from neighboring countries8. However, individual exchanges may be impractical in the context of large avian species, which presents an opportunity for artificial insemination as a viable alternative. It is crucial that such breeding strategies are executed with caution. A thorough genetic assessment must accompany this approach to mitigate the risks associated with outbreeding depression — specifically, the introduction of poorly locally adapted alleles — as well as to confirm the genetic purity of the donor stocks. Previous reports have highlighted the occurrence of hybrids between milky storks and closely related species in both captive and wild populations30,32,33, which could have serious implications for the overall gene pool and genetic integrity of the Thai milky stork population48,49. Moreover, maintaining detailed life history records — such as fecundity, survival rates, growth rates, and health statuses — of captive-bred individuals is essential for developing an effective breeding program and informing reintroduction strategies50. By integrating this information with genetic data, conservation initiatives could significantly enhance the recovery efforts for milky stork populations in Thailand.

As two genetic clusters were found in the current captive Thai milky storks, it would be most appropriate at this moment to propose a reproductive management strategy via combination of keeping the pure genetic backups of these two clusters and making hybridizations between offsprings descended from the two. Specifically, within each cluster, breeding with proper parental pairs based on genetic relatedness revealed in our study [i.e., parental pairs with unrelated history] should be primarily performed (see Supplementary Table S8). This would help maintain the pure genetic stock of each cluster. Later, breeding between offsprings descended from the two should be meticulously conducted under the genetic relatedness consideration. This strategy would not only avoid or minimize inbreeding and its depression, but also keep genetic integrity of the two original clusters for any further management programs. Nonetheless, if competent parental pairs within each cluster become unexpectedly unavailable, given the current small population size, mating between unrelated storks of the two clusters as proposed in Supplementary Table S7 should be pressingly operated to prevent genetic loss of the dwindling Thai milky storks.

The milky stork populations have thus far experienced a substantial decline, with their natural populations primarily confined to Cambodia, Malaysia, and Indonesia. It remains uncertain whether these extant storks are genetically fragmented or should be recognized as a single conservation management unit. Future genetic studies utilizing the polymorphic markers and primers developed in this research, as well as genome-wide SNP data obtained by NGS, are necessary to investigate population connectivity and demographic patterns of the milky stork across Southeast Asia. Such studies would not only shed light on the geographic origins of the Thai milky stork founders but also contribute to the establishment of a critical information database for the global conservation of this endangered species.

Conclusions

This study provides the first comprehensive evaluation of genetic diversity, population structure, and individual genealogical relationships among captive milky storks at NRZ, the sole facility in Thailand where a breeding stock of this endangered species is established and maintained for future reintroduction efforts. Our analyses indicate that the captive population faces a risk of genetic diversity reduction, primarily due to the limited number of founders at the beginning. Notably, the detection of a negative overall inbreeding coefficient, coupled with a high proportion of genetically unrelated individuals, suggests that the current captive stork population remains viable for the use as breeding stock for subsequent generations. This potential effort for continued breeding is contingent upon the implementation of effective strategies aimed at enhancing genetic diversity and mitigating the risk of inbreeding, as outlined in our recommendations.

Methods

Ethical approval

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the ARRIVE guidelines (http://www.ARRIVEguidelines.org) for the ethics of animal research. Experimental protocols conducted in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University (Protocol Review No. 1823015).

Samples and DNA extraction

Blood samples of 48 milky storks were previously collected from NRZ in 2018 by a team of the zoological park and NRZ veterinarians as described in Kaminsin et al.30. This zoo is now the only place in Thailand where milky storks have been maintained as breeding stock. Each bird was captured individually and identified using a mark recapture ring. With continuation to our earlier work, we previously documented the occurrence of three hybrids of milky storks and its sister taxon — the painted stork — in this captive bred due to past hybridization event at DZ30. Consequently, only 45 stork individuals, excluding MS21, MS26, and MS46, that were identified as genetically pure milky storks, were chosen for genetic diversity analyses in this study.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples using FavorPrep™ Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Favorgen Biotech corp., Taiwan) and later utilized as templates for PCR amplification.

Mitochondrial DNA amplification and sequencing

Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were performed to amplify a 1,700 bp segment of the mitochondrial control region using the newly developed primers: STND6F (5'-CCA ACH ACY CCA TAR TAV GGV GAA GG-3') and ST12SR (5'-AAC BGT AAG GTT AGG ACT AAG TCT TT-3'). These primers were designed using a sequence alignment of the complete mitochondrial genomes of related stork species in the family Ciconiidae and other wading bird species retrieved from the GenBank database, including C. ciconia (NC002197), C. boyciana (NC002196), Ciconia maguari (CM030224), Anas platyrhynchos (NC009684), and Anser cygnoides (NC023832). The amplified fragments include partial ND6 gene, complete control region, and partial 12S ribosomal RNA gene. Each PCR was set up for a 25 µL reaction, containing 2.5 µL of genomic DNA, 0.5 µM of each primer, and 1x premix of EmeraldAmp® MAX PCR master mix (Takara, Japan). PCR amplification was proceeded on Bio-Rad T100 (Bio-Rad) under thermal cycling condition: a 3 min denaturing step at 93 °C, then 40 cycles of 93 °C for 30 s, 64 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 3 min, with a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified products were later analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel, stained by SYBR® Safe DNA gel staining dye (Invitrogen™), and visualized under blue light. Nucleotide sequencing was performed using a rapid next-generation sequencing platform or FastNGS service by U2Bio Inc., Thailand.

Microsatellite amplification and genotyping

All 45 specimens were primarily screened and genotyped for 20 microsatellite loci that were originally designed from (i) the wood stork M. americana: WSµ13, WSµ17, WSµ18, WSµ20, WSµ23, and WSµ2451; (ii) the Oriental white stork C. boyciana: Cbo108, Cbo109, and Cbo15152; and (iii) the European white stork C. ciconia: Cc04, Cc06, Cc07, Cc10, Cc37, Cc42, Cc44, Cc50, Cc58, Cc69, and Cc7239,44 (see Supplementary Table S9). These 20 loci included eight polymorphic ones retrieved from Kaminsin et al.30 and 12 loci newly genotyped in this study. The 5’ end of one primer in each primer pair was tagged with fluorescent dyes (6-FAM or HEX, Bionics Inc., South Korea) to facilitate allelic size determination. The microsatellite PCR reactions were carried out in 15 µL volume, containing 1x premix of EmeraldAmp® MAX PCR master mix (Takara, Japan), 0.5 µM of each primer, and 1.5 µL of DNA template. Amplification profiles for all primers were conducted as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s (see details in Supplementary Table S9 for locus-specific annealing temperatures), and extension at 72 °C for 40 s, and then a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were first separated electrophoretically on a 3% (w/v) agarose gel and the desired fluorescent-labeled products were later sent to Bionics Inc. (South Korea) for genotyping. Fragments were sized in comparison to an internal standard size using the GeneMaker® software v.2.6.4 (SoftGenetics, LLC). Moreover, in order to confirm that the amplified fragments are truly homologous microsatellite regions in the milky stork genome, we also sequenced the amplicons of all loci to determine base repetitive and numbers of repeated motifs. One or two homozygous PCR products that showed the largest allelic size in each locus were selected for sequencing at Bionics Inc. using the forward primer.

Sex identification based on CHD gene amplification

Milky storks are phenotypically sexually monomorphic birds although males and females differ significantly in body and beak sizes53, rendering sex identification based on morphology impracticable. In this investigation, sexes of every sample were determined using molecular sexing techniques. The introns of the CHD (chromo-helicase-DNA binding protein) genes on the stork sex chromosome were amplified from genomic DNA using the primers 2550F and 2718R described by Fridolfsson and Ellegren54; CHD-Z and CHD-W genes are located on the Z and W chromosomes, respectively55,56. The sex of each stork individual can be directly determined by size differences of the amplicons presented on 1% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis as male (ZZ) yields a single band of 620 bp, whereas female (ZW) shows two bands of 620 bp and 450 bp.

Data analyses

MtDNA haplotype and phylogenetic relationships

Control region sequences of all samples were manually edited and aligned using CLUSTAL W57 implemented in MEGA v.11.0.658. The number of variable sites (v), average number of pairwise nucleotide differences (k), the number of haplotypes (H), haplotype diversity (h), and nucleotide diversity (π) were computed through DnaSP v.6.12.0359 and used to describe the amount of genetic variation in the stork population examined in this study. Deviations from selective neutrality were assessed using Tajima’s D60 and Fu’s Fs statistic61 in the DnaSP program, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

An alignment of 1,131-bp control region sequences, comprising 45 milky storks derived from this study, one sequence of M. americana (CM069219), and three related taxa retrieved from GenBank database — C. boyciana (NC002196), C. ciconia (NC002197), and C. maguari (MN356211), was constructed for phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using Bayesian inference (BI) and Maximum likelihood (ML) approaches. The best evolutionary model for the alignment was selected using jModelTest v.2.1.1062 based on the Bayesian information criteria (BIC). The best-fit nucleotide substitution model was HKY + G. The BI tree was generated by MrBayes v.3.2.1 program63 with 10,000,000 generations, 1,000-step sampling, and a burn-in of 2,500 generations. The results were visualized in Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v.664. The ML tree was built using IQ-TREE v.2.2.2.665 with HKY + G model based on the BIC and 10,000 bootstrap replicates implemented. The control region sequences of C. boyciana, C. ciconia, and C. maguari were used as outgroups for both analyses. Furthermore, in order to determine maternal relationships among mtDNA haplotypes based on sequence variations, a minimum spanning haplotype network was constructed using PopART v.1.766. The nucleotide sequences of other related storks were also included in this network analysis.

Nuclear genetic diversity, population structure, and genealogical relatedness analyses

Nuclear genetic diversity, including the number of alleles per locus (NA), observed (HO) and expected (HE) heterozygosities, were calculated using GENEPOP v.4.7.567,68. Deviations from the expectations of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE p-value) for each microsatellite locus were tested by GENEPOP based on allele frequencies. FSTAT v.2.9.469 was used to evaluate linkage disequilibrium (LD) between all pairs of loci following multiple testing for statistic significances using Bonferroni correction (p < 0.01). The presence of null allele or null allele frequency (NAF) of all loci was investigated using ML-NullFreq v.1.0.370. The FSTAT was also used for assessing the level of inbreeding within a population or inbreeding coefficient (FIS)71 for all polymorphic loci as well as overall values.

To examine the population genetic structure, the number of genetic cluster (K) of all samples was identified on the basis of microsatellite genotypes using a Bayesian clustering approach implemented in STRUCTURE v.2.3.472. 1,000,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations and a burn-in of 100,000 replications were run using admixture-assumed and correlated allele frequencies without any prior information. The number of K was varied from one to ten, with ten independent runs for each K value. The best K value was chosen based on the highest average log likelihood (Ln P(K)) of the data across the ten runs, as well as the Delta K (ΔK) obtained in StructureSelector73.

To minimize pairings between closely related individuals, relatedness values (r), or the proportion of alleles shared among individuals that are identical by descent (IBD)74 based on population allele frequencies of multilocus microsatellite markers, were estimated using the GenAlEx v.6.51b2 software75,76. Lynch & Ritland’s77 LR estimator multiplied by 2 was utilized to estimate the r values of all pairs of the sampled storks, including female-female, male-male, and male-female pairs, as well as the mean pairwise r value. This estimator generates pairwise relatedness values ranging from -1 to 1, representing a continuous estimate of overall IBD between individuals. In addition to the LR estimator, the maximum likelihood estimator was used for pairwise relatedness estimation through the ML-Relate software v.1.0.378 (https://www.montana.edu/kalinowski/software/ml-relate/index.html). This estimator model gave r values, ranging from 0 to 1. Utilizing two programs helped assure the accuracy of the relatedness estimation and made conclusions in terms of the parents-offspring relationship more robust. In this study, we based our interpretation primarily on r values derived from the GenAlEx because this estimator program provided more elaborate r values, which indicate degrees of relative ranking for genetic relatedness.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Mitochondrial control region sequences are available at the NCBI under GenBank accession numbers PV066040–PV066042.

References

Qiu, J., Zhang, Y. & Ma, J. Wetland habitats supporting waterbird diversity: conservation perspective on biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relationship. J. Environ. Manage. 357, 120663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120663 (2024).

Arntzen, J. W., Abrahams, C., Meilink, W. R. M., Iosif, R. & Zuiderwijk, A. Amphibian decline, pond loss and reduced population connectivity under agricultural intensification over a 38 year period. Biodivers. Conserv. 26, 1411–1430 (2017).

Reid, A. J. et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 94, 849–873 (2019).

Murata, K., Satou, M., Matsushima, K., Satake, S. & Yamamoto, Y. Retrospective estimation of genetic diversity of an extinct Oriental white stork (Ciconia boyciana) population in Japan using mounted specimens and implications for reintroduction programs. Conserv. Genet. 5, 553–560 (2004).

Zhang, B. E. I., Fang, S. G. & Xi, Y. M. Low genetic diversity in the endangered crested ibis Nipponia nippon and implications for conservation. Bird Conserv. Int. 14, 183–190 (2004).

Shephard, J. M., Ogden, R., Tryjanowski, P., Olsson, O. & Galbusera, P. Is population structure in the European white stork determined by flyway permeability rather than translocation history? Ecol. Evol. 3, 4881–4895 (2013).

Purchkoon, N., Salangsing, N., Senanok, S., Noisaward, C. & Poksaward, C. Eastern Sarus Crane Will Be Back. (Zoological Park Organization of Thailand under Royal Patronage of H.M. The King, 2015).

Ebenhard, T. Conservation breeding as a tool for saving animal species from extinction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10, 438–443 (1995).

Fraser, D. J. How well can captive breeding programs conserve biodiversity? A review of salmonids. Evol. Appl. 1, 535–586 (2008).

Ralls, K. & Ballou, J. Captive breeding and reintroduction in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity Vol. 1 (ed. Levin, S. A.) 662–667 (Elsevier Science, 2013).

Frankham, R., Ballou, J. D. & Briscoe, D. A. Introduction to Conservation Genetics (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Robert, A. Captive breeding genetics and reintroduction success. Biol. Conserv. 142, 2915–2922 (2009).

Schulte-Hostedde, A. I. & Mastromonaco, G. F. Integrating evolution in the management of captive zoo populations. Evol. Appl. 8, 413–422 (2015).

Reed, D. H., Briscoe, D. A. & Frankham, R. Inbreeding and extinction: the effect of environmental stress and lineage. Conserv. Genet. 3, 301–307 (2002).

Jamieson, I. G. Founder effects, inbreeding, and loss of genetic diversity in four avian reintroduction programs. Conserv. Biol. 25, 115–123 (2011).

Rahman, F. & Ismail, A. Waterbirds: an important bio-indicator of ecosystem in Waterbirds as an Important Ecosystem Indicator (ed. Faid, R.) 81–91 (Universiti Putra Malaysia Press, 2018).

Kushlan, J. A. Colonial waterbirds as bioindicators of environmental change. Col. Waterbirds 16, 223–251 (1993).

Iqbal, M. & Hasudungan, F. Observations of milky stork Mycteria cinerea during 2001–2007 in South Sumatra province, Indonesia. BirdingASIA 9, 97–99 (2008).

Iqbal, M., Mulyono, H., Riwan, A. & Takari, F. An alarming decrease in the milky stork Mycteria cinerea population on the east coast of South Sumatra province, Indonesia. BirdingASIA 18, 68–70 (2012).

Ismail, A. & Rahman, F. An urgent need for milky stork study in Malaysia. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 35, 407–412 (2012).

BirdLife International. Mycteria cinerea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22697651A93627701. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22697651A93627701.en (2016).

Li, Z. W. D., Yatim, S. H., Howes, J. & Ilias, R. Status overview and recommendations for the conservation of milky stork Mycteria cinerea in Malaysia: final report of the 2004/2006 milky stork field surveys in the Matang Mangrove Forest, Perak. Wetlands International and the Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Peninsular Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. (2006).

Shepherd, C. Observations of milky storks Mycteria cinerea in percut, North Sumatra, Indonesia. BirdingASIA 11, 70–72 (2009).

BirdLife International. Species factsheet: Milky Stork Mycteria cinerea. https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/milky-stork-mycteria-cinerea (2023).

Sanguansombat, W. Thailand red data: birds. http://chm-thai.onep.go.th (2013).

Morioka, H. & Yang, C. -M. A record of the milky stork for Thailand. Jap. J. Ornithol. 38, 149–150 (1990).

Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning. Biodiversity, tendency and threats in Thailand: National Report on the Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity 12–25 (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, 2009).

eBird. eBird: an online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. http://www.ebird.org (2022).

Wongwai, A. et al. A study of migratory waterbirds population and migration timing at the beginning of migration season: a case study of migration seasons of the year 2013–2014. Wildl. Yearb. 17, 51–72 (2019).

Kaminsin, D. et al. Detecting introgressive hybridization to maintain genetic integrity in endangered large waterbird: a case study in milky stork. Sci. Rep. 13, 8892. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35566-x (2023).

Witzenberger, K. A. & Hochkirch, A. Ex situ conservation genetics: a review of molecular studies on the genetic consequences of captive breeding programmes for endangered animal species. Biodivers. Conserv. 20, 1843–1861 (2011).

Yee, E. Y. S., Zainuddin, Z. Z., Ismail, A., Yap, C. K. & Tan, S. G. Identification of hybrids of painted and milky storks using FTA card-collected blood, molecular markers, and morphologies. Biochem. Genet. 51, 789–799 (2013).

Baveja, P., Tang, Q., Lee, J. G. H. & Rheindt, F. E. Impact of genomic leakage on the conservation of the endangered milky stork. Biol. Conserv. 229, 59–66 (2019).

Frankham, R. Genetic considerations in reintroduction programmes for top-order, terrestrial predators in Reintroduction of Top-Order Predators (eds. Hayward, M. W. & Somers, M. J.) 371–387 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

Lopes, I. F. et al. Genetic status of the wood stork (Mycteria americana) from the southeastern United States and the Brazilian Pantanal as revealed by mitochondrial DNA analysis. Genet. Mol. Res. 10, 1910–1922 (2011).

Yamamoto, Y. New haplotypes in the mitochondrial control region of Oriental white storks Ciconia boyciana. Reintroduction 1, 77–80 (2011).

Ruokonen, M. & Kvist, L. Structure and evolution of the avian mitochondrial control region. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 23, 422–432 (2002).

Edwards, A. W. F. G. H. Hardy (1908) and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Genetics 179, 1143–1150 (2008).

Feldman Turjeman, S., Centeno-Cuadros, A. & Nathan, R. Isolation and characterization of novel polymorphic microsatellite markers for the white stork, Ciconia ciconia: applications in individual–based and population genetics. Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 39, 11–16 (2016).

Llanes-Quevedo, A., Alfonso-Gonzalez, M., Cárdenas Mena, R., Rodríguez, C. & Espinosa-López, G. Microsatellite variability of the wood stork Mycteria americana (Aves, Ciconiidae) in Cuba: implications for its conservation. Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 41, 357–364 (2018).

Sharma, B. B., Banerjee, B. D. & Urfi, A. J. A preliminary study of cross-amplified microsatellite loci using molted feathers from a near-threatened painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala) population of North India as a DNA source. BMC Res. Notes 10, 604 (2017).

Jangtarwan, K. et al. Take one step backward to move forward: assessment of genetic diversity and population structure of captive Asian woolly-necked storks (Ciconia episcopus). PLoS ONE 14, e0223726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223726 (2019).

Eo, S. H., Doyle, J. M. & DeWoody, J. A. Genetic diversity in birds is associated with body mass and habitat type. J. Zool. 283, 220–226 (2010).

Shephard, J. M., Galbusera, P., Hellemans, B., Jusic, A. & Akhandaf, Y. Isolation and characterization of a new suite of microsatellite markers in the European white stork, Ciconia ciconia. Conserv. Genet. 10, 1525–1528 (2009).

Ceballos, F. C., Joshi, P. K., Clark, D. W., Ramsay, M. & Wilson, J. F. Runs of homozygosity: windows into population history and trait architecture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 220–234 (2018).

Kardos, M., Taylor, H. R., Ellegren, H., Luikart, G. & Allendorf, F. W. Genomics advances the study of inbreeding depression in the wild. Evol. Appl. 9, 1205–1218 (2016).

Sato, Y., Humble, E. & Ogden, R. Genomic data reveal strong differentiation and reduced genetic diversity in island golden eagle populations. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 143, blad172 (2024).

Dowling, T. E. & Secor, C. L. The role of hybridization and introgression in the diversification of animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 28, 593–619 (1997).

Todesco, M. et al. Hybridization and extinction. Evol. Appl. 9, 892–908 (2016).

Ismail, A., Rahman, F., Kin, D. K. S., Ramli, M. N. H. & Ngah, M. Current status of the milky stork captive breeding program in zoo Negara and its importance to the stork population in Malaysia. Trop. Nat. Hist. 11, 75–80 (2011).

Tomasulo-Seccomandi, A. M. et al. Development of microsatellite DNA loci from the wood stork (Aves, ciconiidae, Mycteria americana). Mol. Ecol. Notes 3, 563–566 (2003).

Wang, H. et al. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite DNA markers for the Oriental white stork, Ciconia boyciana. Zoolog. Sci. 28, 606–608 (2011).

Ong, H. K. et al. Morphometric sex determination of milky and painted storks in captivity. Zoo Biol. 31, 219–228 (2012).

Fridolfsson, A. K. & Ellegren, H. A simple and universal method for molecular sexing of non-ratite birds. J. Avian Biol. 30, 116–121 (1999).

Griffiths, R. & Tiwari, B. Sex of the last wild Spix’s macaw. Nature 375, 454 (1995).

Ellegren, H. First gene on the avian W chromosome (CHD) provides a tag for universal sexing of non-ratite birds. Proc. Biol. Sci. 263, 1635–1641 (1996).

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (1994).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Rozas, J. et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3299–3302 (2017).

Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595 (1989).

Fu, Y. X. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection. Genetics 147, 915–925 (1997).

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772 (2012).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82 (2024).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Leigh, J. W. & Bryant, D. POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 1110–1116 (2015).

Raymond, M. & Rousset, F. GENEPOP (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J. Hered. 86, 248–249 (1995).

Rousset, F. GENEPOP’007: a complete re-implementation of the genepop software for Windows and Linux. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 8, 103–106 (2008).

Goudet, J. FSTAT (version 2.9.4), a program to estimate and test population genetics parameters. https://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.html. Updated from Goudet (1995). (2003).

Kalinowski, S. T. & Taper, M. L. Maximum likelihood estimation of the frequency of null alleles at microsatellite loci. Conserv. Genet. 7, 991–995 (2006).

Weir, B. S. & Cockerham, C. C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38, 1358–1370 (1984).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000).

Li, Y. L. & Liu, J. X. StructureSelector: a web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 176–177 (2018).

Blouin, M. S. DNA-based methods for pedigree reconstruction and kinship analysis in natural populations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 503–511 (2003).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539 (2012).

Smouse, P. E., Banks, S. C. & Peakall, R. Converting quadratic entropy to diversity: both animals and alleles are diverse, but some are more diverse than others. PLoS ONE 12, e0185499. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185499 (2017).

Lynch, M. & Ritland, K. Estimation of pairwise relatedness with molecular markers. Genetics 152, 1753–1766 (1999).

Kalinowski, S. T., Wagner, A. P. & Taper, M. L. ML-Relate: a computer program for maximum likelihood estimation of relatedness and relationship. Mol. Ecol. Notes 6, 576–579 (2006).

Acknowledgements

A. Wiwegweaw was financially supported by the Plant Genetic Conservation Project under the Royal Initiative of Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn – Chulalongkorn University. We acknowledge the Zoological Park Organization of Thailand, and Nakhon Ratchasima Zoo for giving official permission to conduct this research. We express our sincere gratitude to the veterinarian team and staffs of the Nakhon Ratchasima Zoo for sample collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W. conceived the concept and designed the experiment; A.W., D.K., C.C., N.W., and N.K. carried out the experiment and performed data analysis; A.W., D.K., S.S., and W.C. performed field collection; A.W. drafted the original manuscript; A.W., C.C., and N.W. reviewed and revised the manuscript; A.W. acquired research funding; A.W., D.K., C.C., N.W., N.K., S.S., and W.C. read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiwegweaw, A., Kaminsin, D., Chantangsi, C. et al. Genetic structure of the endangered milky stork (Mycteria cinerea) in Thailand with implications for captive breeding and reintroduction. Sci Rep 15, 26402 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10726-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10726-3