Abstract

Based on observations from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), we conducted a comprehensive study of two contact binaries, V752 Cen and HT Vir, in 2+2-type hierarchical quadruple stellar systems. TESS continuous light curves (LCs) reveal that \(\Delta m_{max}\) exhibits random-walk-like or quasi-periodic variations, whereas \(\Delta m_{min}\), shows small jumps. Using the Wilson–Devinney program, we obtained six sets of photometric solutions to trace the migration and evolution of a cool starspot on the stellar surface. Notably, such spot activity can significantly alter LCs and may even reverse minima depths, as observed around BJD\(_{\text {TDB}}\)2459282 for V752 Cen. From the TESS time-series LCs, we determined 529 eclipse timings (ETs). For HT Vir, the residuals of the primary and secondary minima show a strong anti-correlation, indicating the presence of starspots. Based on all available ETs, we constructed \((O-C)\) curves, which could be described by an upward parabola with the light-time effect (LiTE) induced by a third body. Given the third light of \(\ell _3\sim 4.0\%\) for HT Vir, we estimate the mass of the third body to be \(M_3=0.66(2)~\textrm{M}_{\odot }\). For V752 Cen, the minimum mass of the third body is \(M_3=0.84(2)~\textrm{M}_{\odot }\), suggesting it may be a compact star. Finally, we updated the absolute parameters of the two studied binaries, whose components are normal or slightly evolved main-sequence stars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

W Ursae Majoris (W UMa)-type contact binaries consist of main sequence (MS) components of spectral types F–K1. Most of these systems have orbital periods of approximately 0.2–0.6 day2. Their light curves (LCs) typically displays nearly equal minima, suggestive of two components with comparable effective temperatures. Observationally, contact binaries can be classified into two subclasses: A-type binaries have the deeper eclipse at transit, whereas W-type systems have it at occultation3. In A-type systems, the more massive star is larger and hotter. In contrast, the more massive star is larger but cooler than its companion in W-type systems4. Despite considerable research, several aspects of contact binaries, such as the energy exchange between two components through large-scale circulation in the equatorial plane5,6, remain unclear. Detailed studies of binaries could provide insights into stellar astrophysical processes, such as Kozai cycles with tidal friction7, mass transfer, angular momentum loss8,9, and merging10. Space-based photometry of binary systems has been reviewed by Southworth11, from Voyager to the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS)12. Notably, such photometry provides nearly noiseless continuous observations over months or even years, serving as a valuable resource for studying binary systems13,14.

Many contact binaries as rapid ratators display signatures of stellar magnetic activity, such as X-ray emission15,16, irregular spot-like structures in Doppler images17, H\(\alpha\) emission excess18,19, variations in eclipse timing (ET)20,21, and the O’Connell effect22,23. Notably, most contact binaries are now known to reside within triple systems24,25,26. Recently, Tokovinin et al.27 and Borkovits et al.28 catalogued numerous low-mass hierarchical triple stellar systems. In this context, we selected two short-period contact binaries, V752 Cen and HT Vir, which are members of multiple systems. Their key parameters are summarized in Table 1. Using their TESS LCs and ETs, we explored spot migration based on the intrinsic light variability, as well as the presence of additional companions via the light-time effect (LiTE)29. Previous findings related to these binaries are outlined in the following text:

V752 Cen [TESS Input Catalog (TIC) 157175641, 1RXS J114247.8-354832] was found as a variable star by Strohmeier et al.30. Later, Bond31 reported it to be an eclipsing binary with a period of 0.3703 d. Sisteró & Castore de Sisteró32,33 published the UBV light and radial velocity (RV) curves for this system, determining it to be a contact binary with a mass ratio of \(q=0.311(\pm 0.029)\). Barone et al.34 also derived the absolute parameters for this binary. Schumacher35 identified weak, sharply lined features in the spectra, implying the presence of a lower-mass detached binary with a period of 5.147 d. Together, V752 Cen and this fainter detached binary constitute a triple-line spectroscopic quadruple system with a wide orbit. Recently, Zhou et al.36 and Innis & Coates37 obtained photometric elements and analysed the orbital period variations. Mallama & Pavlov38 and Zhou et al.36 proposed that the orbital period, once constant, suddenly started increasing, potentially owing to interactions with the wider spectroscopic binary.

HT Vir [TIC 392909786, HD 119931A, ADS 9019Bb] is a W UMa variable and member of the visual binary ADS 9019. Its orbital period and light variable amplitude have been measured to be 0.40767 d and 0.42 magnitudes, respectively39. Pribulla & Rucinski24 identified HT Vir as Component B of the visual pair, with Component A being a single-lined binary. Lu et al.40 measured the RVs and concluded that HT Vir is an A-type contact binary with a mass ratio of \(q=0.812(8)\). Additionally, the authors found that Component A is a spectroscopic binary with an orbital period of 32.45 d. Moreover, Component A is approximately two times fainter than Component B (i.e., the contact binary) at its light maxima. Therefore, the visual binary ADS 9019 is in fact a 2+2-type quadruple stellar system, with Components A and B orbiting each other on a 274.0 y astrometric orbit41. Walker & Chambliss42 published UBV photoelectric LCs and performed the first detailed analysis of this binary. Notably, Zola et al.43 incorrectly used the secondary ET as the reference epoch (i.e., HJD 2453117.4702) and derived a W-type solution with a mass ratio \(q=1.227\) based on the BVR LCs. Moreover, Liao & Qian44 deduced a cyclic variation with a period of \(30.5~\textrm{years}\).

TESS photometry

V752 Cen and HT Vir were observed by the TESS, and their continuous LCs were downloaded from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST), available at https://mast.stsci.edu/. Specifically, we obtained six-sector data sets with a 120 s cadence, as listed in Table 1. The notation “\(\text {S}63_{2023}\)” in this table, for example, refers to Sector 63 observed in the year 2023. For V752 Cen, the observing duration exceeded over 100 days, fully displaying its intrinsic light variability. We adopted the simple aperture photometry (SAP) among the TESS products. Although SAP LCs can exhibit long-term astrophysical trends, the Presearch Data Conditioning SAP (PDCSAP) LCs may exclude many observations, and the eclipse depths in PDCSAP are typically greater than those in SAP LCs45.

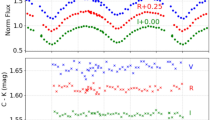

TESS operates in an elliptical, 2:1 lunar-synchronous orbit with a period of 13.7 d. Owing to the large pixel size of TESS instruments, they inevitably capture scattered light from the Earth and Moon in each sector. The amount of contaminating flux varies across sectors (https://tess.mit.edu/observations/scattered-light/). However, this scattered light varies smoothly over a longer timescale relative to the periods of the investigated binaries. Specifically, within half of the eclipsing binary’s period (\(\sim 0.2\) d), both light maxima/minima are nearly equally affected by the contamination. Therefore, the difference between light maxima or minima and the variable light amplitude remain negligibly affected. Consequently, the effect of scattered light on the intrinsic variability of LCs can be considered negligible. To quantify intrinsic variations, we computed three typical values, i.e., the variable light amplitude \(\text {m}_{var}\)=Min.I-Max.I, difference between two maxima \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}\)=Max.I-Max.II, and difference between two minima \(\Delta \text {m}_{min}\)=Min.I-Min.II, for each complete period of the LCs. These values, extracted from the six segmented LCs, are given in Table 2. Each LC segment was denoted by a notation such as “LC2282”, where “2282” denotes the observing middle date minus the TESS reference, BJD\(_{\text {TDB}}\) 2457000 (where BJD\(_{\text {TDB}}\) denotes the Barycentric Julian Date in the Barycentric Dynamical Time). Figure 1 displays the trends of \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}\) and \(\Delta \text {m}_{min}\) over the observing time. \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}\) exhibits random-walk-like or quasi-periodic variations, whereas \(\Delta \text {m}_{min}\) demonstrates jumps. To compare the intrinsic light variations, we intercepted three segments for each binary, whose phase-folded LCs are shown in Fig. 2. The intrinsic variability for V752 Cen covers nearly the entire phase from 0.1 to 0.9, as shown in Fig. 2a. In contrast, for HT Vir, the variability occurs only around phases 0.45 to 0.85 in Fig. 2b. More importantly, the secondary eclipse for V752 Cen is deeper than the primary eclipse by up to 0.01 mag for LC2282 (observed around \(\text {BJD}_{\text {TDB}}\)2459282), which may result from spot activity.

Methods

-

ET Determination and Period Analysis

From the continuous TESS LCs for each sector, we extracted individual minima and their uncertainties using the Kwee–van Woerden method46. Although this method tends to underestimate errors47,48, its accuracy is sufficient in the case of symmetric data or complete LCs, as discussed by Poro et al.49. From the six-sector LCs, we determined 529 ETs for V752 Cen and 204 ETs for HT Vir. All ETs and their standard deviations are listed in Table 3, with the complete data provided as table3.pdf in the Supplementary Materials. While we analyzed the period variations, all ETs in BJD\(_{TDB }\) were converted into the heliocentric Julian date (HJD) by subtracting 69.184 s50.

The orbital period changes can provide information on mass transfer, mass loss, light time effect (hereafter LiTE) and other mechansims. Based on all available ETs, we constructed \((O-C)\) diagrams (i.e., observed minus computed ETs), as shown in Fig. 3. The \((O-C)_i\) curve exhibited a long-term increase with minor fluctuations. Therefore, we fit the residuals of ETs using a LiTE term superimposed on an upward quadratic curve (i.e., Q+LiTE), as follows:

where \(a_{12}\), e, i, \(\omega\), and \(\nu\) have been described by Irwin51. During the computational process, the weights were set as the inverse-square of the standard deviations, following the approach of Yang52. All fitted parameters and standard deviations were determined simultaneously. To evaluate the possibility of overfitting, we used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) method53. Assuming a normal distribution for the model errors, the BIC can be simplified to54,

where n and k denote the number of data points and number of modelled parameters, respectively. Table 4 lists the values calculated using only the LiTE terms, \(\text {BIC}_{\text {LiTE}}\), and Eq. (1), \(\text {BIC}_{\text {Q+LiTE}}\). The results show that \(\text {BIC}_{\text {Q+LiTE}}\) is considerably smaller than \(\text {BIC}_{\text {LiTE}}\) for each binary. Statistically, the \((O-C)_i\) curves are fitted better by Eq. (1) due to the lower BIC value. Therefore, Eq. (1) can effectively describe the initial residual curve.

-

Photometric solutions by the W-D code

Figure 4 shows three segments of LCs intercepted from the TESS data for each binary. We deduced photometric solutions by the Wilson–Devinney (W–D) binary star modelling code55,56,57 (ftp://ftp.astro.ufl.edu/pub/wilson/lcdc2015). Previous results have shown that two systems are typical contact binaries. Therefore, we adopted the mode 3 (i.e., contact configuration) of the W–D program. From the spectroscopic solutions33,40, we fixed the mass ratios, \(q=3.212\) for V752 Cen and \(q=0.812\) for HT Vir.

For V752 Cen, the mean effective temperature of the more massive component was fixed as \(6138\pm 324\textrm{K}\), as indicated in Gaia DR258. For HT Vir, we adopted the value \(6100\textrm{K}\)43, corresponding to an F8V star. The gravity-darkening coefficient was set as \(g_{1,2}=0.32\), and the bolometric albedo was \(A_{1,2}=0.5\), appropriate for stars with convective envelopes59,60. In solving LCs, the adjustable parameters included the orbital inclination, temperature of the less massive component, modified surface potentials, component bandpass luminosities, and third light. To model the significant asymmetries in the LCs, we assume that the spot is positioned on the stellar equator (i.e., colatitude \(\theta =90^\circ\)) to trace the variable longitude over time. Other three parameters of the spot (longitude, angular radius, and dimensionless temperature factor) are adjustable. The relative equivalent radius \(\bar{r}\) for each component was computed using the pole, side, and back radii (from the output of the W–D Code), as well as the point radius at the inner Lagrange point for a contact binary61). Given that one component star consists of two rotational hemi-ellipsoids, the relative equivalent radius could be expressed as

where \(r_{pole}\), \(r_{side}\), \(r_{back}\), and \(r_{point}\) denote the pole, side, back, and point radii, respectively.

ET residuals versus epoch numbers for two contact binaries. The continuous and dotted lines are plotted using Eq. (1) and its parabolic part, respectively.

Individual results

-

V752 Cen

Based on 36 visual (“vi”) ETs, Mallama & Pavlov38 inferred a sudden jump in the period. Similarly, Zhou et al.36 suggested an initial sudden jump, followed by a continuous increase. However, such discontinuous changes are highly improbable. Therefore, we assumed that the period undergoes continuous change. Over the past five years, we accumulated 399 ETs from three sectors of TESS (Nos. 36, 37, & 64) and five new light minimum times from the OMC database (http://binaries.boulder.swri.edu/binaries/omc/). To ensure consistency with previous results36, we retained the original low-precision ETs, specifically, the 36 vi minimum light times, to study the period variations. Overall, we compiled 36 vi, 56 ground-based photoelectric (“pe”) and charge-coupled device (“CCD”), 86 SuperWASP62, and 529 TESS ETs. The new linear ephemeris was refined as follows:

Using this ephemeris, we computed the initial residuals for all ETs, as shown in the upper panel of Fig. 3a. Applying Eq. (1) to describe the \((O-C)_i\) curve, we obtained the fitted parameters presented in Table 4. The modulation period was \(P_{mod}=60.49(\pm 0.57)~\textrm{y}\). The overall trend of the period change was well fitted. As shown in the lower panel of Fig. 3a, no regularity was found, supporting the assumption of continuous period variation.

To solve the LCs, we adopted a mass ratio of \(q=3.212\)33 and an effective temperature of \(T_2=6138~\textrm{K}\) from Gaia DR363. The third light \(L_3\) was set to be an adjustable parameter. As shown in Fig. 1a, the LC segments exhibit evident asymmetry. The differences between two light maxima are \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}=-0.^m014\) for LC2282 and \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}=+0.^m012\) for LC3038. As shown in Fig. 2a, the total eclipse lasts approximately 50 min. For LC2282, the secondary eclipse is deeper than the primary eclipse, which could be attributed to spot migration. Three sets of photometric solutions are presented in Table 5, where the third light contributes to approximately \(\ell _3\sim 0.6\%\) of the total light of the binary star. The parameters of the cool starspot from LC2282 are \(\lambda =286.5^\circ\), \(\gamma =9.57^\circ\), and \(T_s/T=0.711\), indicating that spot migration could reverse the depths of the light minima.

-

HT Vir

Liao & Qian44 reported a 30.5-y sinusoidal oscillation based on 56 ETs. Fifteen years later, we reassembled all available light minimum times to identify period changes. The ET dataset includes 104 ground-based pe/CCD measurements and 204 TESS measurements ranging from 1979 to 2022. Based on the light elements of \(\text {Min.I}=\text {HJD}~2444044.5178(2)=0.40767009(8)\times E\)39, we refined a new ephemeris from all ETs as follows:

Next, we computed the initial residuals \((O-C)_i\), shown in the upper panel of Fig. 3b. Additionally, we used Eq. (1) to describe the \((O-C)_i\) curve. The fitted results are presented in Table 4, where the modulation period is \(P_{mod}=39.58(\pm 0.15)~\textrm{y}\). Although small gaps exist, the final residuals \((O-C)_f\)s were fitted well.

Based on RV curves, Lu et al.40 concluded that HT Vir is an A-type binary with a mass ratio \(q=0.812(8)\). However, Zola et al.43 incorrectly identified it as a W-type system, with \(q=1.227\). According to the correct epoch of the primary eclipse, HT Vir should be an A-type contact binary. Thus, to solve the LCs, we fixed the mass ratio as \(q=0.812(8)\)40 and temperature as \(T_1=6100~\textrm{K}\)43. From Fig. 1b, \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}\) is always larger than zero, indicating that Max.II is fainter than Max.I (i.e., the system exhibits a positive O’Connell effect). Based on the symmetric LC2690 segment, we can easily obtain a solution with the third light \(L_3\). For LC1950, \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}\) is as large as 0.020 mag. After assuming a cool starspot on star 1, a photometric solution can be obtained. From Table 5, the third lights and fill-out factors approximate to \(\ell _{3}\sim 4\%\) and \(f\sim 9\%\), causally coinciding with the results derived by Zola et al.43.

Discussion and conclusion

As discussed, we first analysed the period variations, characterized by a secular period increase with cyclic oscillations. This trend has also been observed for other contact binaries, such as HI Leo and V523 Cas64, as well as RZ Com and VW LMi65. Subsequently, we deduced the photometric solutions from six intercepted LCs, which exhibited a variable O’Connell effect. Assuming a spot on the more massive component, we traced the activity and evolution of the cool starspot.

Activity of the cool starspot

Tran et al.20 suggested that the anti-correlation between the primary and secondary ET variations could be attributable to a starspot that is continuously visible around the orbit and slowly changes its longitude over long timescales of weeks to months. The initial residuals of the TESS ETs for HT Vir are shown in Fig. 5, where the primary and secondary ETs show a strong anti-correlation. Moreover, V752 Cen is an X-ray emitter. Therefore, the asymmetric LCs of two binaries may be explained by the cool starspot on the stellar surface.

Although photometric solutions can track the spot migration, we could not model the LCs across multiple cycles. Therefore, we inferred the location of the cool starspot from typical segment LCs. As shown in Fig. 1, the LCs exhibit intrinsic light variabilities. \(\Delta \text {m}_{max}\) and \(\Delta \text {m}_{min}\) vary over time, which may be explained by the rapid spot evolution on orbital or even suborbital timescales66,67. Based on the spotted solutions in Table 5, we constructed three-dimensional configurations at different phases, as shown in Fig. 6. For V752 Cen, the spot first emerges in panel (a), disappears in (b), and reemerges in (c). The cool starspot is adequately strong during LC2282 to produce the reversed minima depths observed in Fig. 2a. This may cause the system to appear as a W–type instead of a A–type. In the case of HT Vir, the spot becomes visible in panels (d) and (e), but disappears in panel (f).

Absolute parameters and evolutionary states

To minimize the influence of spots on the binary parameters, we adopted unspotted photometric solutions. The semi-amplitudes of RV curves, \(K_1\) and \(K_2\), were effectively measured by Sisteró & Castrore de Sisteró33 for V752 Cen and Lu et al.40 for HT Vir. The binary’s absolute parameters were calculated using the following expression,

where \(R_{1,2}\) denotes \(a\times \bar{r}_{1,2}\), and a is the separation between both components. Combined with the photometric solutions from \(\text {LC2317}\) for V752 Cen and \(\text {LC2690}\) for HT Vir, we determined all absolute parameters, as summarized in Table 6. This table also presents the parameters derived in prior studies. For the W-type binary V752 Cen, the temperature of \(6138~\textrm{K}\) from the Gaia data should be the temperature of the massive component rather than that of the less massive component36. Moreover, Zola et al.43 incorrectly specified the W-type solution. Therefore, we updated the absolute parameters of two contact binaries.

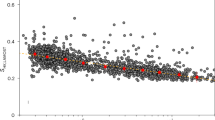

To illustrate the binary evolutionary states, we plotted the mass and luminosity of the two binaries on \(\log {M}\)–\(\log {L}\) and \(\log {T}\)–\(\log {L}\) diagrams. In Fig. 7, the zero-age main sequence (ZAMS) and terminal age main sequence (TAMS) lines were constructed using the binary-star evolution algorithm68. The black solid and open circles in Fig. 7 represent the primary and secondary components, respectively, of the 118 well-studied short-period contact binaries69. The primary components for both binaries lie close to the ZAMS line, indicating that they are normal MS stars. The secondary component of V752 Cen is located between the ZAMS and TAMS lines, indicating that it is a slightly evolved MS star. The secondary component of HT Vir lies well above the ZAMS line, with its large size and luminosity resulting from energy transfer70.

Third component around the contact binary

For close binaries, cyclic variations are generally interpreted using magnetic activity cycles71 and the LiTE produced by a third body29. As indicated in Table 4, the modulation periods are \(P_{mod}\sim 40\) years for HT Vir and \(\sim 60\) y for V752 Cen. For active binaries, Hall72 suggested that the variation in the gravitational quadrupole moment \(\Delta Q\) may result in the observed cyclic variations. Thus, we computed \(\Delta Q\) using the known equations73,

After inserting the fitted and absolute parameters, we obtained the values of \(\Delta Q_{1,2}\) for both components, as outlined in Table 4. For close binaries74, \(\Delta Q\) is of the order of \(10^{51}\)–\(10^{52}\textrm{g}~\textrm{cm}^{2}\). However, \(\Delta Q_{1,2}\sim 10^{49}\textrm{g}~\textrm{cm}^{2}\) in Table 4 implies that cyclic magnetic activity may not explain the observed variations.

In contrast, LiTE may result in the observed cyclic variation. The mass function of the third body is given as follows:

where \(a_{12}\sin {i}=A\times c\); \(P_{mod}\) and \(M_{1,2}\) are presented in AU and years, respectively; and \(M_\odot\). G is the gravitational constant. We can obtain f(m) after inserting the values of \(P_{mod}\) and \(a_{12}\sin {i}\). For a given inclination i, we can determine \(M_3\) iteratively using Eq.(8).

Assuming the third-light contribution comes entirely from the third body, we can examine the third light from photometric solutions and the inferred mass from LiTE. For HT Vir, the third-light contribution is \(\ell _3\sim 4.0\%\), resulting in a luminosity of \(L_3=0.146~\textrm{L}_{\odot }\). According to the mass–luminosity relation \(L\propto M^\alpha\) (\(\alpha =4.572\) for \(0.45~\textrm{M}_{\odot }\le M \le 0.72~\textrm{M}_{\odot }\))75, the mass of the third body may be estimated to be \(L_3=0.656~\textrm{M}_{\odot }\) for an inclination of \(i=23.3^\circ\). Therefore, the third companion to HT Vir may be a dwarf star. For V752 Cen, the minimum mass of the body is \(M_{3\text {min}}=0.836(\pm 0.019)\textrm{M}_{\odot }\) for an inclination of \(i=90^\circ\). The corresponding luminosity for a MS star is approximately \(L_3=0.357~\textrm{L}\odot\), derived using the relation \(L\sim M^\alpha\) (\(\alpha =5.743\) for \(0.72~\textrm{M}_{\odot }\le M \le 1.05~\textrm{M}_{\odot }\))75. From the photometric solutions, the third light contributes to \(\ell _3\sim 0.6\%\) of the total light, which corresponds to \(L_3=0.018~\textrm{L}\odot\), considerably smaller than that for an MS star, \(L_3=0.357~\textrm{L}\odot\). Thus, the third body of V752 Cen is likely to be a compact companion, whose physical properties must be further examined. This scenario has been observed in other contact binaries, such as V410 Aur76. Moreover, we obtained \(K_{RV}\) and \(\alpha\) to assess whether a third body was observationally resolved. LiTE is typically accompanied by changes in the systemic radial velocity of the eclipsing pair as follows77,

The angular separation from the centre of mass is \(\alpha =a_{12}\sin {i}/d\), where the distance from Earth, d, is computed by the parallaxes in Table 1. All derived parameters, \(M_3\), \(a_{12}\), \(K_{RV}\), and \(\alpha\), are listed in Table 4. Thus, the tertiary companion is expected to orbit around the contact binary and may be detected by spectroscopy, direct imaging, and astrometry using adaptive optics24,25,78. For the two binaries, the light-time orbit effect via ETs and the third light indirectly identify the existence of the third body. If there is indeed a tertiary component orbiting these binaries, the two spectroscopic binaries may constitute a hierarchical multiple stellar systems. Our results must be verified by high-resolution spectroscopy, photometry, and astrometry in future work.

Data availability

TESS datasets generated and/or analysed for V752 Cen and HT Vir are available in the MAST repository, persistent web link to: https://mast.stsci.edu/portal/Mashup/Clients/Mast/Portal.html. The complete Table 3 is presented as table3.pdf in the Supplementary Materials.

References

Abdel Rahman, H. I. & Darwish, M. Physical characterization of late-type contact binary systems observed by LAMOST: a comprehensive statistical analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 21648. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48507-5 (2023).

Poro, A. et al. BSN: The First Photometric Study of 10 Contact Binary Systems from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Astron. J. 168, 272. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ad8345 (2024).

Binnendijk, L. The orbital elements of W Ursae Majoris systems. Vistas in Astron. 12, 217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0083-6656(70)90041-3 (1970).

Ruckinski, S. Contact binaries: observational properties. in Interacting Binary Stars (eds. Pringle, J. E. & Wade, R. A.) (Cambridge University Press), 85(1985).

Stȩpień, K. Large-scale circulations and energy transport in contact binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 397, 857–867. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14981.x (2009).

Rucinski, S. K. Lessons from the high-resolution spectroscopy of AW UMa and Epsilon CrA: Is the Lucy model valid?. Astron. J. 169, 82. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ad9f26 (2025).

Kisseleva-Eggleton, L. & Eggleton, P. P. Kozai Cycles and Tidal Friction. ASPC 435, 169–172 (2010).

Cehula, J. & Pejcha, O. A theory of mass transfer in binary stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 524, 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad1862 (2023).

Willcox, R., Macleod, M., Mandel, IIya & Hirai, R. The Impact of Angular Momentum Loss on the Outcomes of Binary Mass Transfer. Astrophys. J. 958, 138. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/acffb1 (2023).

Tylenda, R. et al. V1309 Scorpii: merger of a contact binary. Astron. Astrophys. 528, 114. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201016221 (2011).

Southworth, J. Space-based photometry of binary stars: from Voyager to TESS. Universe 7, 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe7100369 (2021).

Ricker, G. R. et al. Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). IATIS 1, 0140003. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JATIS.1.1.014003 (2015).

Green, M. J. et al. 15 000 ellipsoidal binary candidates in TESS: Orbital periods, binary fraction, and tertiary companions. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 522, 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad915 (2023).

Prs̆a, A. et al. TESS eclipsing binary stars. I. short-cadence observations of 4584 eclipsing binaries in sectors 1-26. Astronphys. J. Suppl. Ser. 258, 16–37. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ac324a (2022).

Voges, W. et al. The ROSAT all-sky survey bright source catalogue. Astron. Astrophys. 349, 389–405. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.astro-ph/9909315 (1999).

Geske, M. T., Gettel, S. J. & McKay, T. A. A ROSAT survey of contact binary stars. Astron. J. 131, 633–637. https://doi.org/10.1086/498018 (2006).

Barnes, J. R. et al. High-resolution doppler images of the spotted contact binary AE Phe. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 348, 1321–1331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07452.x (2004).

Hall, J. C. Stellar chromospheric activity. Living Rev. Sol. Physics 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.12942/lrsp-2008-2 (2008).

Zhang, L. et al. Stellar Parameters and Spectroscopic Properties of TESS Objects Observed in the LAMOST Low- and Medium-resolution Spectral Survey. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 264, 17. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ac9b28 (2023).

Tran, K. et al. The anticorrelated nature of the primary and secondary eclipse timing variations for the Kepler contact binaries. Astrophys. J. 774, 81. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/774/1/81 (2013).

Meng, Zi-Bin. et al. OO Leo: An active contact binary with possible solar-like differential rotation. Astrophys. J. 971, 113. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad571e (2024).

O’Connell, D. J. K. The so-called periastron effect in close eclipsing binaries: New variable stars (fifth list). Publ. Riverview Coll. Obs. 2, 85–99 (1951).

Milone, E. E. The peculiar binary RT Lacertae. Astron. J. 73, 708–711. https://doi.org/10.1086/110682 (1968).

Pribulla, T. & Rucinski, S. M. Contact binaries with additional components. I. The Extant Data. Astron. J. 131, 2986–3007. https://doi.org/10.1086/503871 (2006).

D’Angelo, C., van Kerkwijk, M. H. & Rucinski, S. M. Contact binaries with additional components. II. a spectroscopic search for faint tertiaries. Astron. J. 132, 650–662. https://doi.org/10.1086/505265 (2006).

Moe, M. & Di Stefano, R. Mind Your Ps and Qs: The Interrelation between Period (P) and Mass-ratio (Q) Distributions of Binary Stars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 230, 15. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/aa6fb6 (2017).

Tokovinin, A. Resolved Gaia triples. Astrophys. J. 926, 1. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ac4584 (2022).

Borkovits, T. Eclipsing Binaries in dynamically interacting close, multiple systems. Galaxies 10, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies10010009 (2022).

Irwin, J. B. The determination of a light-time orbit. Astrophys. J. 116, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1086/145604 (1952).

Strohmeier, W., Knigge, R. & Ott, H. Bright Southern BV-Stars. Inf. Bull. Var. Stars 70, 1–7 (1964).

Bond, H. E. Three eclipsing binaries found spectroscopically. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 82, 1065–1069. https://doi.org/10.1086/129004 (1970).

Sisteró, R. . F. . & Castrore de Sisteró, M. E. UBV light variation and orbital elements of HD 101799. Astron. J. 78, 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1086/111435 (1973).

Sisteró, R. F. & Castrore de Sisteró, M. E. Radial velocity curves of HD 101799. Astron. J. 79, 391–396. https://doi.org/10.1086/111556 (1974).

Barone, F. et al. Analysis of Contact Binary Systems: AA Ursae Majoris, V752 Centauri, AO Camelopardalis, and V677 Centauri. Astrophys. J. 407, 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1086/172509 (1993).

Schumacher, H. Analysis of the W UMa-type Eclipsing Binary V752 Centauri. ASPC 404, 199–204 (2009).

Zhou, X. et al. V752 Cen - a triple-lined spectroscopic contact binary with sudden and continuous period changes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 489, 4760–4770. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stz2508 (2019).

Innis, J. & Coates, D. New CMOS photometry and archival photographic observations of the W UMa star V752 Cen: extending the O-C record of period changes. Open Eur. J. Var. Stars 224, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.5817/OEJV2022-0224 (2022).

Mallama, A. & Pavlov, H. Sudden period change and dimming of the eclipsing binary V752 centauri. JAVSO 43, 38–39 (2015).

Walker, R. L. The discovery of a W Ursae Majoris variable in the visual binary system ADS9019. Inf. Bull. Var. Stars bf 2486, 1–2 (1984).

Lu, W., Rucinski, S. M. & Ogloza, W. Radial velocity studies of close binary stars. IV. Astron. J. 122, 402–412. https://doi.org/10.1086/321131 (2001).

Zasche, P. & Wolf, M. Combining astrometry with the light-time effect: The case of VW Cep, \(\zeta\) Phe and HT Vir. Astron. Nachr. 328, 928–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/asna.200710828 (2007).

Walker, R. L. & Chambliss, C. R. A W UMa variable in the visual binary system ADS 9019: a UBV photoeletric investigation. Astron. J. 90, 346–353. https://doi.org/10.1086/113738 (1985).

Zola, S. et al. Physical parameters of components in close binary systems. V. Acta Astron. 55, 389–405. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0903.1365 (2005).

Liao, W.-P. & Qian, S.-B. Detection of a cyclic period change in the W UMa-type system HT Virginis. Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan 62, 521–524. https://doi.org/10.1093/pasj/62.3.521 (2010).

Yuangui, Yang & Shuang, Wang. TESS light-curve modelling and period study of four eclipsing binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 531, 3823–3838. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stae1352 (2024).

Kwee, K. K. & van Woerden, H. A method for computing accurately the epoch of minimum of an eclipsing variable. Bull. Astron. Ins. Nerth. 12, 137–140 (1956).

Pribulla, T. et al. The Dwarf project: Eclipsing binaries - precise clocks to discover exoplanets. Astron. Nachr. 333, 754–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/asna.201211722 (2012).

Li, M. C. A. et al. A study of the light travel time effect in short-period MOA eclipsing binaries via eclipse timing. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 480, 4557–4577. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty2104 (2018).

Poro, A. et al. The first light curve solutions and period study of BQ Ari. Astron. Letters 47, 402. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063773721060050 (2021).

Eastman, J., Siverd, R. & Gaudi, B. S. Achieving better than 1 minute accuracy in the heliocentric and barycentric julian dates. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 122, 935–946. https://doi.org/10.1086/655938 (2010).

Irwin, J. B. Standard light-time curves. Astron. J. 64, 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1086/107913 (1959).

Yang, Y. .-G. How to compute the light-time orbit effect in close binaries. Sci. China Ser. G.-Phys. Mech. Astron. 39, 637–640. https://doi.org/10.1360/2009-39-4-637 (2009) ([in Chinese]).

Schwartz, G. Estimating the demension of a model. Annals Stat. 6, 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136 (1978).

Priestly, M. B. Spectral analysis and time series London (Academic Press, New York, 1981).

Wilson, R. E. & Devinney, E. J. Realization of accurate close-binary light curves: Application to MR Cygni. Astrophys. J. 166, 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1086/150986 (1971).

Wilson, R. E. & Van Hamme, W. Unification of binary star ephemeris solutions. Astrophys. J. 780, 151. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/780/2/151 (2014).

Wilson, R. E., Devinney, E. J., & Van Hamme, W. WD: Wilson-Devinney binary star modeling. Astrophysics Source Code Library, record ascl: 2004.004.

Andrae, R. et al. Gaia Data Release 2. First stellar parameters from Apsis. Astron. Astrophys. 616, 8. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201732516 (2018).

Lucy, L. B. Gravity-darkening for stars with convective envelopes. Z. Astrophys. 65, 89–92 (1967).

Ruciňski, S. M. The proximity effects in close binary systems II the bolometric reflection effect for stars with deep convective envelopes. Acta Astron. 19, 153–245 (1969).

Kopal, Z. Close binary systems (Chapman & Hall, London, 1959).

Pollacco, D. L. et al. The WASP Project and the SuperWASP Cameras. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 118, 1407–1418. https://doi.org/10.1086/508556 (2006).

Hodgkin, S. T. et al. Gaia Early Data Release 3. Gaia photometric science alerts. Astron. Astrophys. 652, 76. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140735 (2021).

Yang, Y. & Wang, S. Light and period variations in Two K-type contact binaries: HI Leo and V523 Cas. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 22, 123012. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-4527/ac9781 (2022).

Nelson, R. H., Terrell, D. & Milone, E. F. A critical review of period analyses and implications for mass exchange in W UMa eclipsing binaries: Paper 4. New Astron. Rev. 97, 101684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newar.2023.101684 (2023).

Csizmadia, S., Patkós, L., Moór, A. & Könyves, V. Photometric study of the contact binary star V861 Herculis. A &A 417, 745–750 (2004).

Sriram, K. et al. A Study of the Kepler K2 Variable EPIC 211957146 Exhibiting a Variable O’ Connell Effect. Astron. J. 153, 231. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/aa6893 (2017).

Hurley, J. R., Tout, C. A. & Pols, O. R. Evolution of binary stars and the effect of tides on binary populations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 329, 897–928. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05038.x (2002).

Poro, A. et al. Investigation of the orbital period and mass relations for W UMa-type contact systems. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 510, 5315–5329. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stab3775 (2022).

Zhang, X. & Qian, S. Orbital period cut-off of W UMa-type contact binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa2166 (2020).

Applegate, J. H. A mechanism for orbital period modulation in close binaries. Astrophys. J. 385, 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1086/170967 (1992).

Hall, D. S. The Relation Between Rs-Canum and Algol. Space Sci. Rev. 50, 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00215932 (1989).

Rovithis-Livaniou, H. et al. Study of the period changes of X Trianguli. Astron. Astrophys. 354, 904–908 (2000).

Lanza, A. F. & Rodonò, M. Orbital period modulation and quadrupole moment changes in magnetically active close binaries. Astron. Astrophys. 349, 887–897 (1999).

Eker, Z., Bakis, V., Bilir, S., et al. Interrelated main-sequence mass-luminosity, mass-radius, and mass-effective temperature relations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.479 5491–5511 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty1834.

Liao, W.-P. et al. A single-lined spectroscopic binary companion to an active and deep contact binary in a quintuple stellar system. Astrophys. J. 927, 183. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ac5038 (2022).

Mayer, P. Eclipsing binaries with light-time effect. Bull. Astron. Inss. Czechosl 41, 231–236 (1990).

Rucinski, S. M. Contact binaries with additional components. III. a search using adaptive optics. Astron. J. 134, 2353–2365. https://doi.org/10.1086/523353 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the two anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions and comments. This study was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11873003), Natural Science Foundation of the Educational Department of Anhui Province (No. 2023AH040057), and Science Project of Huaibei Normal University (No. RE240049). We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing. Dr Yuangui Yang acknowledges Professor Kreiner for providing his compiled eclipse timings for V752 Cen. Extensive use was made of the SIMBAD database (http://simbad.cds.unistra.fr/simbad/). All photometric data were derived from the TESS mission, publicly available through the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI). The TESS mission was funded by the NASA Science Mission Directorate. This work also made use of data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Gaia (https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), which are processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC). Funding for DPAC is provided by national institutions, especially those participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr Yang Yuangui conducted the majority of this research, except for the photometric solutions, which were computed by Dr Wang Shuang. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Wang, S. Magnetic activities of two contact binaries in quadruple stellar systems. Sci Rep 15, 27202 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10772-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10772-x