Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients frequently exhibit vitamin D deficiency and an imbalance in T helper 17 (Th17) and regulatory T (Treg) cells, which may contribute to disease pathogenesis. Preclinical evidence suggests vitamin D regulates Th17/Treg balance, but the therapeutic effects of supplementation in PD remain unestablished. This randomized controlled trial investigated peripheral blood levels of vitamin D, Treg, and Th17 cells in PD patients, examined their associations with clinical outcomes, and assessed vitamin D3 supplementation’s effects on immunological and motor functions. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 51 PD patients and 50 healthy controls (HCs) were enrolled. Thirty PD patients with vitamin D deficiency were randomized to receive vitamin D3 (n = 15) or placebo (vegetable oil, n = 15) for three months. Serum 25(OH)D3 levels were measured by electrochemiluminescence, and Th17/Treg cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Motor and non-motor symptoms were assessed using standardized scales. Vitamin D3 supplementation significantly increased 25(OH)D3 levels (p < 0.05), reduced Th17 cells (4.62 ± 1.09 to 3.25 ± 1.14, p = 0.003), and elevated Tregs (3.25 ± 0.90 to 4.52 ± 0.95, p = 0.003). Motor function (UPDRS and UPDRS-III) improved in the vitamin D3 group (p < 0.001), while no changes were observed in the placebo group. This preliminary study suggests that vitamin D3 supplementation may restore Th17/Treg balance and potentially alleviate motor symptoms in vitamin D-deficient PD patients, indicating a possible therapeutic strategy.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT:06539260. Registered 05 August 2024 - Retrospectively registered, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06539260.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease(PD), the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, affects approximately 1–2% of individuals aged 65 and older. Estimates indicate that by 2040, the global prevalence of PD will exceed 12 million individuals worldwide. However, the exact etiology of PD remains unclear, with multiple factors implicated1. The intricate mechanism of neurodegeneration in PD has not to be fully elucidated, but it is believed to encompass a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, immune modulation, and other factors.

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone that performs many other functions in addition to its well-known role in calcium homeostasis. There is extensive evidence from in vitro and animal studies indicating that vitamin D plays crucial roles in cell proliferation and differentiation, neurotrophic regulation and neuroprotection, neurotransmission, immune regulation, and neural plasticity2,3,4,5,6. Furthermore, the expression of vitamin D receptor (VDR) and CYP27B1 is particularly abundant in the substantia nigra, a brain region rich in dopaminergic neurons7. As a fat-soluble hormone, vitamin D can cross the blood‒brain barrier, which serves as indirect evidence supporting its role in the central nervous system8.

The role of T lymphocytes in Parkinson’s disease development is multifaceted and complex. Initial research indicated that T lymphocytes contribute to the degeneration of midbrain substantia nigra neurons through infiltration and destructive mechanisms. In contrast, emerging evidence suggests that Tregs may exert protective effects on dopaminergic neurons. There are four main subtypes of CD4+ T cells: Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cells. Among them, Th17 cells are a proinflammatory subtype, whereas Treg cells are an anti-inflammatory subtype. The balance between Th17 and Treg cell levels plays a crucial role in maintaining immune homeostasis and inducing antigen-specific immune tolerance9,10. Various autoimmune diseases are associated with the disruption of this balance11. Research over the past decade has shown that these immune alterations are not limited to the periphery but also extend to the central nervous system, where they promote the progression of neurodegenerative diseases12. In cellular models, Th17 cells have been demonstrated to disrupt and cross the blood‒brain barrier and are associated with increased neuroinflammation in central nervous system pathologies13,14. Within the central nervous system, Treg cells actively promote neural system recovery through the inhibition of astrocyte proliferation, with particular emphasis on their role in ischemic stroke and neuroinflammatory diseases15. Similar results have also been reported in studies involving PD patients, where Th17 cells were found to induce the apoptosis of midbrain neurons16whereas Tregs exhibited a protective effect on dopamine neurons17. Many studies have reported increased proportions of Th17 cells and decreased proportions and impaired functions of Treg cells in patients with Parkinson’s disease18,19.

Vitamin D can regulate Th17 and Treg cells primarily by inducing the expression of the FOXP3 gene in naive CD4+ T cells20,21. The VDR binds to VDREs within the FOXP3 gene, enabling vitamin D to directly upregulate Foxp3 expression, thereby promoting the differentiation and expression of Treg cells. Conversely, Foxp3 inhibits the expression of RORγt in CD4+ T cells22. RORγt is the primary transcription regulator of Th17 cells, promoting and maintaining their specificity as Th17 cells. Therefore, inhibiting RORγt expression leads to the suppression of Th17 differentiation and expression. In summary, vitamin D regulates the balance between Th17 and Treg cells, playing a key role in maintaining immune homeostasis.

Low vitamin D levels in PD patients have been recognized for more than 15 years23and numerous clinical studies have corroborated the imbalance of Th17 and Treg levels in these patients18,19,24. This study aimed to detect the expression levels of vitamin D, Tregs, and Th17 cells in the peripheral blood of PD patients, explore the influence of Treg/Th17 imbalance on PD progression, and further investigate the impact of vitamin D intervention on this imbalance and clinical outcomes. We hope to gain a deeper understanding of the role of vitamin D deficiency and the Treg/Th17 imbalance in PD.

Materials and methods

Design of the study

This study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (NCT: 06539260, 06/08/2024) that administered a three-month supply of vitamin D3 and a placebo(vegetable oil) to patients with PD who had low levels of vitamin D. This study obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of Suzhou Hospital of Anhui Medical University, with approval number A2023024. The procedures used in this study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed informed consent to participate in the study and were informed of their right to withdraw at any point during the trial.

Participants

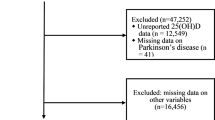

From January 2023 to March 2024, 51 PD patients were recruited. All subjects were evaluated and treated in the Parkinson’s Out-patient and In-patient department of the Neurology Department at Suzhou Hospital of Anhui Medical University. Fifty partners or volunteers of PD patients, matched by sex and age, are selected from Suzhou Hospital of Anhui Medical University to form a healthy control(HC) group. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) Meet the diagnostic criteria for PD established by the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank. (2) Age between 45 and 80 years. (3) Have a disease duration of less than ten years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Have related vitamin D metabolic diseases (such as renal failure, severe liver damage, inherited 1α-hydroxylase deficiency, etc.). (2) Have immune system diseases. (3) Have a history of disabling cerebrovascular disease. (4) Have first- or second-degree relatives with PD. (5) Have severe dementia, depression, or severe mental illness.

Randomization and masking

For the PD patients included in the study, analyses were conducted on their peripheral blood vitamin D levels. PD patients with low vitamin D levels were divided into two groups at a 1:1 ratio to receive vitamin D3 and PL. Randomization was performed via an Excel random number generator. Both vitamin D3 and the PL were placed in identical bottles labeled only with numbers and containing no additional information. The patient is administered either one 5000-unit Vitamin D2 softgel capsule or one placebo capsule orally every 5 days. Product allocation and randomization were carried out by an independent researcher. All parties involved—including assessing physicians performing scale evaluations, data analysis personnel, and patients—remained blinded to treatment allocation until database lock. Unblinding occurred only after completion of the final statistical analysis.

Outcome

The primary endpoint of this study focused on the changes observed from baseline (T0) to the 3-month mark (T1). We evaluated PD patients via a comprehensive set of scales, including the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), Berg Balance Scale (Breg), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS), and Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS). All patients underwent scale assessments at 1.5 h after medication administration (the peak drug concentration period) in order to minimize the impact of the wearing-off phenomenon on the evaluation.

During the initial T0 stage, we analyzed the peripheral blood levels of Th17, Treg, and Vit D in the PD patients and healthy volunteers. Among the PD patients with low vitamin D levels, we randomly assigned them into two groups: one to receive vitamin D3 supplementation and the other to receive PL. At the T1 stage, we followed up with both groups of PD patients to reassess the indicators and monitor any changes (Fig. 1).

Elecsys method

The serum 25(OH)D3 concentration was measured via the Elecsys method on a Roche electrochemiluminescence fully automated immunoassay analyzer. According to the guidelines of the Endocrine Society, normal vitamin D levels are defined as ≥ 30 ng/mL, 20–30 ng/mL is defined as insufficient, and vitamin deficiency is defined as ≤ 20 ng/mL25.

Flow cytometry

Venous blood withdrawal was performed after a night of fasting, between 8:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m., into heparin lithium anticoagulant tubes. The tubes were subsequently coded and stored at room temperature until processing, which occurred 12 h after collection, to ensure homogeneous treatment of all the samples.

Blood was diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640, mixed with leukocyte activation cocktail (3 µL/mL, BD Pharmingen, 550583), and incubated for 4–6 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. After hemolysis (BD Pharmingen), cells were washed, surface-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 (BD Pharmingen, 555332) and PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-CD8 (BioLegend, 341051), fixed/permeabilized (BD Fixation/Permeabilization Kit, 554714), and intracellularly stained with PE-conjugated anti-IL-17 A (BD Pharmingen, 560436).

For Tregs, blood was surface-stained with CD4-FITC (BD Pharmingen, 566911) and CD25-PE (BD Pharmingen, 555432), lysed, fixed/permeabilized (eBioscience FOXP3/TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR STAIN BUFFER, 00-5523-00), and intranuclearly stained with Foxp3-APC (eBioscience, 17-4776-41).

Acquisition was then performed on a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer. CD3+CD8−IL-17+ cells were identified as Th17 cells, whereas CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells were identified as Treg cells. Lymphocytes are recognized on the basis of their classical forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) signals. The data were analyzed via FlowJo software (version 10.8.1).

Statistical analysis

In this study, SPSS 26.0 and GraphPad Prism v.9 software were used for data analysis. Descriptive statistical methods were employed to analyze all the data gathered during the research process. For intergroup comparisons, an independent sample t test was conducted, a paired sample t test was used for comparisons before and after the follow-up. Pearson correlation analysis was applied to data adhering to a normal distribution, whereas Spearman correlation analysis was employed for data deviating from a normal distribution. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

This study included a total of 51 PD patients and 50 healthy individuals, all of whom were of Chinese ethnicity and fulfilled the established inclusion criteria. The PD group included 29 males and 22 females, with a mean age of 69.6 ± 11.0 years. The HCs included 26 males and 24 females, with a mean age of 65.3 ± 10.9 years. No statistically significant differences were observed in sex composition or age between the two groups (p > 0.05). The PD group, with a mean disease duration of 5.8 ± 4.1 years and receiving a mean daily levodopa equivalent dose of 513 ± 280 mg, presented a mean H-Y grade of 2.32 ± 0.90, an average UPDRS score of 45.76 ± 23.06, a mean UPDRS-III score of 26.35 ± 13.56, an average Breg score of 43.45 ± 12.18, a mean MMSE score of 21.46 ± 7.07, an average MoCA score of 18.32 ± 7.51, a mean SDS self-rating depression scale score of 45.85 ± 13.47, a mean SAS self-rating anxiety scale score of 44.20 ± 12.50, and an average PDSS score of 100.82 ± 23.48, as indicated in (Table 1).The PD patients enrolled were categorized into a normal vitamin D level group (Vit D ≥ 30 ng/ml), consisting of 21 patients, and a low vitamin D level group (Vit D < 30 ng/ml), comprising 30 patients, on the basis of their baseline vitamin D levels. The low vitamin D group was subsequently randomly divided into two subgroups, a VitD3 group and a PL group, each comprising 15 patients. Importantly, no complications arose during or following vitamin D supplementation for any of the subjects with vitamin D deficiency.

Th17/Treg imbalance and vitamin D3 deficiency in PD

To investigate changes in CD4+ T-cell subsets in the peripheral blood, we first evaluated the percentages of CD4+ T-cell subsets (Th17 and Treg) in 51 PD patients and 50 healthy controls. Compared with the HCs, the PD cohort presented significant differences in Th17 levels (3.78 ± 1.33 vs. 2.30 ± 0.79, t = 6.799, p < 0.001; Fig. 2a) and Treg levels (4.16 ± 1.29 vs. 4.64 ± 0.97, t = -2.142, p = 0.035; Fig. 2b). Additionally, there was a significant difference in the serum 25(OH) D3 level between the PD cohort and the HC cohort (28.98 ± 8.10 vs. 35.80 ± 6.96, t = -4.531; p < 0.001; Fig. 2c).

Th17, Treg, and serum 25(OH)D3 differences between PD patients and HCs. (a) FACS analysis of Th17 cells(CD3 + CD8− IL-17+ )in the peripheral blood of PD patients and healthy controls. (b) FACS analysis of Treg cells(CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3+) in the peripheral blood of PD patients and healthy controls. (c) The total Vitamin D concentration in the plasma of PD patients and healthy controls was determined by ELISA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Vitamin D3 modulates Th17/Treg balance and improves motor symptoms in PD

There were 30 vitamin D-deficient PD patients randomized into the VitD3 subgroup (n = 15) and PL subgroup (n = 15). Baseline characteristics are presented in (Table 2). Following three months of intervention, the VitD3 subgroup demonstrated a significant reduction in Th17 levels (4.62 ± 1.09 to 3.25 ± 1.14; p = 0.003; Fig. 3a), whereas the PL subgroup showed no significant change (p > 0.05; Fig. 3a). Concurrently, Treg levels increased significantly in the VitD3 subgroup (3.25 ± 0.90 vs. 4.52 ± 0.95; p = 0.003; Fig. 3b), but remained unchanged in the PL subgroup (p > 0.05; Fig. 3b). Motor assessment revealed significant improvements in the VitD3 subgroup for both UPDRS (57.00 ± 20.86 to 52.27 ± 21.38; p = 0.003) and UPDRS-III scores (32.40 ± 11.70 to 28.13 ± 12.44; p < 0.001), though Berg Balance scores showed no significant change (39.73 ± 13.36 vs. 40.60 ± 12.91; p = 0.400; Fig. 3c–e). No significant changes occurred in the PL subgroup (Supplementary Table 1).

Impact of vitamin D3 intervention on immune and motor outcomes in vitamin D-deficient PD patients group. (a) The Th17 cells in the peripheral blood of the VitD and PL groups were compared at T0 and T1. FACS analysis was performed on Th17 cells (CD3 + CD8− IL-17+ ) in the peripheral blood of the VitD group at T0 and T1. (b) The Treg cells in the peripheral blood of the VitD and PL groups were compared at T0 and T1. FACS analysis was performed on Treg cells (CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3+ ) in the peripheral blood of the VitD group at T0 and T1. (c) The UPDRS scale of the VitD and PL groups were compared at T0 and T1. (d) The UPDRS-III scale of the VitD and PL groups were compared at T0 and T1. (e) The Breg scale of the VitD and PL groups were compared at T0 and T1. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Intergroup comparison of change scores (Δ = T1 - T0) further confirmed greater improvements in the VitD3 group across primary endpoints: serum vitamin D (Δ = 8.46 ± 4.04 vs. 2.04 ± 4.05; p = 0.001), Th17 reduction (Δ = -1.37 ± 1.52% vs. -0.37 ± 1.03%; p = 0.034), and Treg elevation (Δ = 1.27 ± 1.38% vs. -0.21 ± 0.77%; p = 0.016). Motor outcomes similarly favored the VitD3 group, with greater reductions in UPDRS-III (Δ = -4.27 ± 3.77 vs. 0.40 ± 1.84; p = 0.001) and total UPDRS scores (Δ = -4.73 ± 5.19 vs. 0.73 ± 2.52; p = 0.001). Berg Balance changes showed no significant between-group difference (p = 0.102) (Table 3). Collectively, these results demonstrate vitamin D3 supplementation specifically ameliorates immune dysregulation and motor symptoms in vitamin D-deficient PD patients, with efficacy superior to placebo.

Vitamin D3 exhibits positive correlation with Tregs and negative association with Th17s

We conducted a correlation analysis on a total of 101 data sets from the PD group and the HC group. The analysis revealed a positive correlation between vitamin D levels in peripheral blood and the percentage of Tregs (r = 0.526, p < 0.001; Fig. 4a) and a negative correlation with the percentage of Th17 cells (r = -0.635, p < 0.001; Fig. 4b).

Association of vitamin D with Treg and Th17 cell in PD and HC groups. (a) Correlation between Treg cells and the Vitamin D concentration in the plasma of PD patients(51) and healthy controls (n = 50). (b) Correlation between Th17 cells and the Vitamin D concentration in the plasma of PD patients(51) and healthy controls (n = 50).

Correlations between PD-related scores and Th17, treg, and vitamin D levels

The proportion of Th17 cells was positively correlated with both the UPDRS and the UPDRS-III score (r = 0.412, p = 0.003 and r = 0.432, p = 0.002, respectively) and negatively correlated with the Breg balance scale (r = -0.302, p = 0.031). The proportion of Treg cells was negatively correlated with the UPDRS and UPDRS-III scores (r = -0.504, p < 0.001 and r = -0.540, p < 0.001, respectively) and positively correlated with the Breg balance scale (r = 0.382, p = 0.006). A correlation analysis between vitamin D levels and UPDRS and UPDRS-III scores among PD patients revealed a negative correlation (r = -0.494, p < 0.001 and r = -0.549, p < 0.001, respectively) and a positive correlation with Breg (r = 0.419, p = 0.002), as indicated in (Table 2). These results indicate that the severity of motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease patients is correlated with the levels of Th17, Treg, and vitamin D. The MMSE score of PD patients is positively correlated with Th17 levels but negatively correlated with vitamin D levels. The MoCA score is positively correlated with Th17 levels and negatively correlated with Treg and vitamin D levels. On the other hand, no correlation was observed between the SDS and SAS scores of PD patients and the levels of Th17, Treg, and vitamin D. Additionally, the PDSS score positively correlated with Treg but was not correlated with Th17 and vitamin D, as indicated in (Table 4).

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the average vitamin D level in PD patients is lower than that in healthy controls, which is consistent with the results of several previous clinical studies23. Additionally, PD patients have a higher Th17/Treg ratio than healthy individuals do. Upon comprehensive analysis, we observed a significant correlation between the levels of 25(OH) D3 in human peripheral blood and Th17 and Treg cells. This finding is in line with our hypothesis that 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 interacts with the vitamin D receptor on the surface of CD4+ T cells, participating in their differentiation and expression and promoting the expression and differentiation of Treg cells while inhibiting the differentiation and expression of Th17 cells. In our assessment of PD patients using motor and cognitive scales, we found an association between their vitamin D levels, T helper cell subsets, and both their motor and cognitive functions.

A three-month follow-up was conducted on both the VitD3 group and the PL group. The results revealed that the levels of 25(OH) D3 in the peripheral blood of the VitD3 group were increased, and the levels of Th17 and Treg cells tended toward those of the normal population. Furthermore, compared with their preintervention levels and those of the PL group at the three-month follow-up, the motor function of the VitD3 group had improved.

The role of vitamin D in PD has been extensively studied. In some studies, vitamin D deficiency has been observed among PD patients26. Research has revealed a correlation between the severity of motor impairments in PD patients and their peripheral blood vitamin D levels27,28and our study yielded similar results. In 2010, a longitudinal study based on a health survey of the Finnish population revealed that individuals with low vitamin D levels had a 65% greater probability of developing Parkinson’s disease than did those with high vitamin D levels29. These findings indirectly support the role of vitamin D in the onset and progression of PD. Vitamin D can achieve neuroprotective effects by inhibiting the early aggregation of α-synuclein (α-Syn), especially in neurodegenerative diseases30. A study on the treatment of Parkinson’s disease in animal models with vitamin D revealed that vitamin D has neuroprotective effects by attenuating proinflammatory processes and upregulating anti-inflammatory processes in animal models of PD31. Vitamin D mediates the secretion and expression of inflammatory factors, which may be the pathway through which it influences the onset and progression of PD. In 1988, McGeer et al. discovered HLA-DR-reactive microglia in the postmortem substantia nigra tissue of Parkinson’s disease patients32which was one of the earliest lines of evidence linking neuroinflammation to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Microglia, monocytes, and infiltrating T cells, which migrate around α-syn in PD patients’ substantia nigra, suggest both the role of innate and adaptive immunity in PD33. A recent study revealed that α-Syn levels in PD patients are associated with the severity of motor symptoms and an imbalance of Th17/Treg cells18. Furthermore, a previous study suggested that α-Syn impairs the stability of Tregs and promotes the differentiation of Th17 cells in PD18. Contact between Th17 cells and midbrain neurons can directly lead to the apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons16,34and IL-17 has a destructive effect on the blood‒brain barrier35. Conversely, Treg cells can significantly protect the survival of midbrain dopaminergic neurons17which also indirectly indicates that an imbalance of Th17/Treg cells in PD patients may exacerbate clinical symptoms. Treg cells play a significant role in reducing the beta-amyloid protein load in Alzheimer’s patients, restoring brain homeostasis, and improving learning and memory36. Similarly, our study revealed a clear correlation between Treg levels and cognitive function in PD patients, suggesting that improving Treg levels may be a potential therapeutic approach for PD patients with cognitive issues.

α-Syn promotes the differentiation of Th17 cells and activates intracellular inflammatory pathways through autoimmune effects18and low vitamin D levels may exacerbate this situation30. Either through the direct immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D or through the immune pathways mediated by α-syn, low vitamin D levels lead to an imbalance between Th17 cells and Treg cells37causing damage to substantia nigra neurons16,17. We believe that this pathway represents a promising direction for future research on the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease and may lead to the discovery of new treatments.

This study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability of the results to a limited scope. Second, the observed vitamin D deficiency in PD patients could stem from reduced outdoor activity and inadequate sunlight exposure due to motor disorders, subsequently hindering vitamin D synthesis. Future studies should explore whether reduced outdoor activity directly contributes to vitamin D deficiency in PD patients through longitudinal monitoring of sun exposure and dietary intake. Third, while our study revealed improvements in Th17 and Treg levels, as well as motor function, among PD patients receiving vitamin D supplementation, we remain unable to definitively attribute the motor improvement solely to the restoration of neural function resulting from the improved Th17/Treg balance.

In the future, further experiments are needed to explore the deeper mechanisms by which vitamin D affects the balance between Th17 and Treg cells and to verify the neuroprotective effect of vitamin D on PD patients through improvements in their autoimmune status. This study is preliminary and requires more cases to improve the research.

Conclusions

These preliminary findings demonstrate that vitamin D3 regulates the Th17/Treg balance, and this immunomodulatory effect may be linked to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Our results suggest that normalizing vitamin D levels could benefit PD patients with deficiency, potentially improving motor function and delaying disability progression. Critically, future large-scale studies are required to confirm these observations and establish clinical efficacy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dorsey, E. R. et al. The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. J. Parkinsons Dis. 8, S3–S8. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-181474 (2018).

Dankers, W. et al. Vitamin D in autoimmunity: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front. Immunol. 7, 697. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00697 (2016).

Li, N. et al. Vitamin D promotes remyelination by suppressing c-Myc and inducing oligodendrocyte precursor cell differentiation after traumatic spinal cord injury. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18 (20220829), 5391–5404. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.73673 (2022).

Meza-Meza, M. R., Ruiz-Ballesteros, A. I. & de la Cruz-Mosso, U. Functional effects of vitamin D: from nutrient to Immunomodulator. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 3042–306220201223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1862753 (2022).

Chen, C. S. et al. Vitamin D insufficiency as a risk factor for paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in SWOG S0221. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 21, 1172–1180 e1173. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.7062 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Vitamin D improves cognitive impairment and alleviates ferroptosis via the Nrf2 signaling pathway in aging mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 20231018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242015315 (2023).

Eyles, D. W. et al. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1α-hydroxylase in human brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 29, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.08.006 (2005).

DeLuca, G. C. et al. Review: the role of vitamin D in nervous system health and disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 39, 458–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12020 (2013).

Maddur, M. S. et al. Th17 cells: biology, pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and therapeutic strategies. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 8–1820120526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.044 (2012).

Duffy, S. S. et al. The role of regulatory T cells in nervous system pathologies. J. Neurosci. Res. 96, 951–96820170510. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24073 (2018).

Qin, Y., Gao, C. & Luo, J. Metabolism characteristics of Th17 and regulatory T cells in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 13, 828191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.828191 (2022).

Anderson, K. M. O. K. & Estes, K. A. Dual destructive and protective roles of adaptive immunity in neurodegenerative disorders. Transl neurodegener. Translational Neurodegeneration. 13, 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-9158-3-25 (2014).

Charabati, M. et al. DICAM promotes TH17 lymphocyte trafficking across the blood-brain barrier during autoimmune neuroinflammation. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abj0473 (2022).

Tahmasebinia, F. & Pourgholaminejad, A. The role of Th17 cells in auto-inflammatory neurological disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 79, 408–41620170729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.07.023 (2017).

Ito, M. et al. Brain regulatory T cells suppress astrogliosis and potentiate neurological recovery. Nature 565 (20190102), 246–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0824-5 (2019).

Sommer, A. et al. Th17 lymphocytes induce neuronal cell death in a human iPSC-Based model of parkinson’s disease. Cell. Stem Cell. 23, 123–131e126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2018.06.015 (2018).

Park, T. Y. et al. Co-transplantation of autologous T(reg) cells in a cell therapy for parkinson’s disease. Nature 619, 606–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06300-4 (2023).

Li, J. et al. alpha-Synuclein induces Th17 differentiation and impairs the function and stability of Tregs by promoting RORC transcription in parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 108 (20221104), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2022.10.023 (2023).

Espinosa-Cardenas, R. et al. Immunomodulatory effect and clinical outcome in parkinson’s disease patients on levodopa-pramipexole combo therapy: A two-year prospective study. J. Neuroimmunol. 347, 577328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577328 (2020).

Jeffery, L. E. et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and IL-2 combine to inhibit T cell production of inflammatory cytokines and promote development of regulatory T cells expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. J. Immunol. 183, 5458–5467. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0803217 (2009).

Kang, S. W. et al. 1,25-Dihyroxyvitamin D3 promotes FOXP3 expression via binding to vitamin D response elements in its conserved noncoding sequence region. J. Immunol. 188 (20120423), 5276–5282. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1101211 (2012).

Zhou, L. et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature 453, 236–240. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06878 (2008).

Evatt, M. L. et al. Prevalence of vitamin d insufficiency in patients with Parkinson disease and alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 65, 1348–1352. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.65.10.1348 (2008).

Chen, Y. et al. Clinical correlation of peripheral CD4+–cell sub–sets, their imbalance and parkinson’s disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 12 (20150729), 6105–6111. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2015.4136 (2015).

Holick, M. F. et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 1911–1930. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0385 (2011).

Zhou, Z. et al. The association between vitamin sunlight exposure, and Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 666–674. 20190123 https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.912840 (2019).

Suzuki, M. et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms, and severity of parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 27, 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.24016 (2012).

Ding, H. et al. Unrecognized vitamin D3 deficiency is common in Parkinson disease. Neurology 1531–1537. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a95818 (2013).

Knekt, P. et al. Serum vitamin D and the risk of Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 67, 808–811. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.120 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Vitamin D inhibits the early aggregation of alpha-Synuclein and modulates exocytosis revealed by electrochemical measurements. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202111853. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202111853 (2022).

Calvello, R. et al. Vitamin D treatment attenuates neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in an animal model of parkinson’s disease, shifting M1 to M2 microglia responses. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 12, 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-016-9720-7 (2017).

McGeer, P. L. & Itagaki, S. Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia Nigra of parkinson’s and alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 38, 1285–1291. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.38.8.1285 (1988).

Tansey, M. G. et al. Inflammation and immune dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 657–673. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00684-6 (2022).

Lindestam Arlehamn, C. S. et al. alpha-Synuclein-specific T cell reactivity is associated with preclinical and early parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 11, 1875. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15626-w (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. IL-17A exacerbates neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration by activating microglia in rodent models of parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 81, 630–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.07.026 (2019).

Yeapuri, P. et al. Amyloid-beta specific regulatory T cells attenuate alzheimer’s disease pathobiology in APP/PS1 mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 18, 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-023-00692-7 (2023).

Ao, T., Kikuta, J. & Ishii, M. The effects of vitamin D on immune system and inflammatory diseases. Biomolecules 11, 20211103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11111624 (2021).

Funding

This research was supported by the Scientific Research Project of the Health Commission of Anhui Province (AHWJ2022b106) and the Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Plan (202204295107020063).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Danfeng Li was responsible for research design, experimental implementation, data analysis, and manuscript writing; Xibo Ma and Mei Li participated in experimental design, experimental implementation, data collection, and result analysis; Wentao Zhang and Ping Zhong provided technical support and participated in manuscript revision and review; Shihua Liu supervised the project, designed the research framework, and conducted the final manuscript review. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles that originated in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with good clinical practice. Institutional review boards or independent ethics committees provided written approval for the study protocol and all amendments (A2023024). All patients provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Ma, X., Zhang, W. et al. Impact of vitamin D3 supplementation on motor functionality and the immune response in Parkinson’s disease patients with vitamin D deficiency. Sci Rep 15, 25154 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10821-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10821-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Neuroimmune crosstalk in Parkinson’s disease: the pivotal role of microglia and infiltrating T cells

Molecular Biology Reports (2025)