Abstract

The market-oriented allocation of Energy-Consuming Rights allows enterprises to trade legally obtained energy consumption quotas on public platforms within regional caps, improving energy efficiency and promoting sustainable development. As an institutional innovation, Energy-consuming rights trading (ECRT) addresses China’s energy and environmental challenges while fostering green transformation. This study employs agent-based modeling to simulate the dynamic interactions among enterprises, governments, and trading platforms under dual constraints of energy consumption and carbon emissions. The results show that: (1) ECRT reduces total energy consumption by 8.1% and carbon emissions by 9.8% compared to regions without trading markets, demonstrating its effectiveness in energy conservation and emission reduction. (2) Paid quotas outperform free quotas, reducing energy consumption by 7.9% and carbon emissions by 6.8%, while stabilizing trading prices and enhancing market activity. (3) High-quality development scenarios improve energy efficiency by 4.4% and reduce carbon emissions by 5%, aligning better with the “dual-carbon” goals. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing ECRT mechanisms and advancing green, low-carbon economic transformation. Policy recommendations include refining quota allocation methods, enhancing market participation, and integrating ECRT with carbon trading systems to maximize efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global greenhouse gas emissions, primarily from fossil fuel combustion, have significantly intensified climate change, necessitating a green and low-carbon transformation of China’s energy system to achieve its “dual-carbon” goals1,2,3,4. In this context, China increasingly acknowledges the crucial role of market mechanisms in resource allocation and is actively constructing a unified national market, as exemplified by the establishment of a national carbon trading market5. As a complementary mechanism to carbon trading, Energy-consuming rights trading (ECRT) is also being explored in various regions across China. ECRT has emerged as an innovative policy designed to enhance energy efficiency and facilitate carbon reduction by efficiently allocating the energy-consuming rights of enterprises while controlling total energy consumption within regions6,7.

Energy-consuming rights, water rights, pollution discharge rights, and carbon emission rights collectively constitute the four fundamental environmental rights. The trading of these environmental rights serves as a pivotal market-based environmental regulation policy, rooted in the principle of leveraging market mechanisms to mitigate environmental externalities - a topic that has garnered substantial academic attention8. The theoretical foundation for environmental rights trading dates back to Coase9, who proposed utilizing market mechanisms and clearly defined property rights to address externalities within social cost analysis. This seminal idea paved the way for the incorporation of environmental equity elements in international markets. Building on Coase’s framework, Dales10 operationalized the theory by introducing emissions trading, marking the first practical application of this concept. Carlson11 further demonstrated the practical benefits by arguing that establishing a sulfur dioxide emission allowance trading market can effectively reduce enterprises’ abatement costs. Subsequent studies have consistently supported the efficacy of market-based trading systems12,13,14.

Parallel to emissions trading, the European Union has promoted the white certificate system as a policy tool for energy saving and emission reduction. This system has proven effective in enhancing energy utilization efficiency and decreasing overall energy consumption15,16,17,18. Inspired by the EU’s initiatives, China began exploring energy-saving trading mechanisms during its 12th Five-Year Plan period. Although energy-saving trading has shown greater applicability to high-energy-consuming enterprises and industries, it still encounters challenges such as underdeveloped market mechanisms, excessive reliance on government oversight, and limited emission reduction strategies8,19. To address these challenges and further refine market-based mechanisms for energy conservation and emissions reduction, China has proposed the ECRT system, building upon the existing energy-saving trading frameworks. Research on ECRT primarily focuses on three aspects: (1) Legal attributes of energy-consuming rights. Scholars debate the classification of these rights, categorizing them as quasi-property rights, concession rights, regulatory property rights, and compound property rights. Despite these discussions, there remains a lack of clear legal definitions for the attributes of energy-consuming rights20,21,22. (2) Initial quota allocation methods. The zero-sum Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method, a non-reimbursable allocation approach, has been widely applied in recent ECRT studies to enhance the fairness of initial quota distributions23,24. (3) Policy effects of ECRT. As a significant market-based environmental regulation tool in China, ECRT has been shown to improve energy-use efficiency, reduce energy consumption and carbon emission intensity, and promote green innovation among enterprises25,26,27,28,29.

Despite the extensive body of literature, existing research predominantly comprises reviews and theoretical analyses, with limited focus on the mechanisms governing initial quota issuance, enterprise trading, and quota clearing within the ECRT system. Additionally, most studies utilize static models for empirical analysis of energy-consuming rights and their influencing factors, lacking exploration into the dynamic evolution mechanisms. To address these gaps, this study employs agent-based modeling (ABM) to simulate government quota allocation and enterprise trading behaviors. ABM facilitates detailed representation of micro-level actions, micro–macro feedback loops, and multi-scenario transitions within a complex-systems framework. By constructing a bottom-up simulation of market-based energy rights allocation, we clarify the underlying allocation mechanisms and assess the ECRT market’s impact on regional energy conservation and carbon reduction, thereby offering theoretical and methodological insights for policy design.

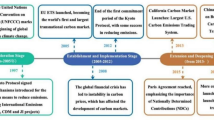

Development of the ECRT market in China

General process for ECRT

Zhejiang, Henan, Fujian, and Sichuan, as the first pilot provinces for ECRT in China, have introduced management measures and policy documents to guide its implementation. These documents define key aspects such as transaction participants, transaction types, procedures, and supervision mechanisms. Additionally, non-pilot regions like Shandong and Anhui have also explored ECRT practices, optimizing trading mechanisms and processes, thereby contributing valuable experience for the establishment of a unified national ECRT market. Based on the practices in pilot regions and public resource trading specifications, the general process of ECRT in China is summarized in Fig. 1.

ECRT involves four key participants: enterprises, government authorities, trading platforms, and third-party auditing organizations. Enterprises, as the primary participants, register on the ECRT platform, report their energy consumption, and decide whether to buy or sell quotas based on their energy-use budgets and energy-saving costs. At the start of each year, enterprises submit an annual energy consumption report for review, and those meeting compliance requirements can continue trading the following year, while non-compliant enterprises face penalties. Government authorities oversee the issuance of initial quotas, establish institutional standards, and regulate the trading process to ensure fairness and efficiency. Quota allocation considers factors such as enterprise energy use, energy-saving performance, and regional energy budgets. Third-party auditing organizations verify enterprise energy use and conduct performance assessments. Trading platforms facilitate the entire process, including information dissemination, transaction witnessing, and data management, ensuring smooth operations. All transactions occur on the platform, with close coordination among all parties to maintain market efficiency.

Current status of ECRT development

The development of China’s ECRT market shows significant regional variation, with pilot provinces like Zhejiang and Fujian demonstrating relatively higher activity, while others, such as Henan and Sichuan, remain less developed. Despite these efforts, the overall market is still in its infancy, facing challenges such as low trading volumes, limited enterprise participation, and underdeveloped secondary markets (Table 1).

Active pilot regions

Zhejiang and Fujian have made notable progress in ECRT implementation. Zhejiang, as one of the earliest pilot provinces, launched its program in 2015, focusing on incremental trading for new energy-using enterprises. By December 2023, the province achieved a cumulative trading volume of 3.94 million tons of coal equivalent (tce). However, most transactions occurred between the government and enterprises, with minimal enterprise-to-enterprise trading, indicating an underdeveloped secondary market. Similarly, Fujian adopted a diversified quota allocation approach tailored to specific industries, such as cement and thermal power. While the province initially achieved a cumulative turnover of 2.2 million tce, trading activity has stagnated in recent years, partly due to overlapping compliance requirements with carbon emissions trading, which discourages enterprise participation.

Regions with limited progress

Henan and Sichuan have established foundational frameworks but face challenges in market activity. Henan’s “1 + 4” pilot system targets key industries with high energy consumption, yet by December 2023, the cumulative transaction volume was only 214,000 tce, reflecting low participation. Sichuan launched its trading platform in 2019, focusing on industries such as steel and cement, but market activity has been minimal, with only two transactions recorded in 2019 and no significant progress since.

Exploratory efforts in non-pilot regions

Some non-pilot regions have begun exploring ECRT mechanisms. For instance, Qingdao initiated its pilot program in 2022, focusing on incremental coal trading for high-energy-consuming industries, completing six transactions in 2023. Heilongjiang, however, remains at the simulation stage, with only one mock transaction completed.

In summary, while pilot regions have accumulated valuable experience, the ECRT market in China remains immature. Key challenges include low trading volumes, limited enterprise participation, and the lack of a robust secondary market. Further exploration of market mechanisms and policy refinements are needed to promote the efficient circulation of energy-use rights and enhance market activity.

Problems in china’s ECRT market

Despite progress in pilot regions, China’s ECRT market faces several challenges that hinder its development and effectiveness. The development of China’s ECRT market remains constrained by imperfections in quota and trading mechanisms, highlighting the need to refine market-oriented allocation models based on pilot experiences. These issues can be categorized into three main areas:

(1) Incomplete legal and policy frameworks

The legal status and property rights of ECRT remain unclear, limiting its potential. While several provinces have issued policy documents to promote ECRT, most are advocacy-oriented rather than providing concrete guidance. Key aspects such as trading rules, institutional frameworks, and regulatory systems lack uniformity, leading to fragmented trading mechanisms across regions. This inconsistency complicates the establishment of a unified national market. Additionally, overlaps between ECRT and carbon emissions trading create redundancy. ECRT focuses on controlling total energy consumption, while carbon trading targets greenhouse gas emissions. However, both rely on similar data and are managed by different authorities, causing issues such as double compliance and inefficient coordination. Harmonizing these two mechanisms remains a critical challenge.

(2) Limited market activity and inefficient resource allocation

The ECRT market is still in its early stages, with low participation and limited trading activity. Many enterprises show little interest in trading due to unclear benefits and limited demand, while existing transactions are mostly concentrated in the primary market between governments and enterprises. Enterprise-to-enterprise trading in the secondary market is minimal, reflecting the lack of a robust market mechanism. This indicates that the “visible hand” of government and the “invisible hand” of market forces have not yet achieved effective synergy. As a result, the market has failed to fully realize its role in optimizing the allocation of energy resources, relying heavily on government intervention rather than organic market dynamics.

(3) Slow progress in pilot construction and demonstration

The slow pace of pilot implementation has limited the ECRT market’s impact. The system adds complexity for enterprises, increasing learning and compliance costs, which dampens their willingness to invest in new projects or participate in the market. For incremental transactions, enterprises must secure energy-use quotas, adding another layer of administrative burden. For stock trading, transitioning initial quotas from free to paid allocations would directly raise production costs. As a result, many regions remain hesitant to fully implement ECRT. Some have issued policies but lack substantive trading platforms, while others have built platforms but conducted few or no market-oriented transactions. This “all talk, no action” approach delays the market’s development and undermines its credibility.

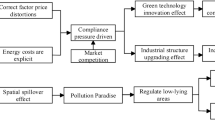

Agent-based modeling framework for ECRT market analysis

The model description follows the ODD framework protocol, starting from three aspects: overview, design concept, and details30.

Overview

Purpose

By simulating the government’s issuance of initial quotas and the trading of energy-consuming rights indexes among enterprises, we analyze the impacts of different mechanism rules on the ECRT market, explore the optimal path to achieve regional energy saving and emission reduction through the market-oriented allocation of energy-consuming rights, and provide reference for the decision-making of relevant departments.

Entities, variables and scales

The entities in the model are heterogeneous, differing in their attributes, functions, and behavioral rules. The model includes three main types of entities: enterprises, government, and trading platforms. Each enterprise acts as an independent agent, making decisions based on its own behavioral rules and trading energy-consuming rights indicators with other enterprises according to its energy usage. The government issues initial energy-consuming rights quotas to enterprises while considering factors such as economic development levels and energy-saving and emission reduction targets. Additionally, it establishes trading rules to effectively regulate the market. The trading platform is responsible for collecting and analyzing trading data. A schematic diagram illustrating the relationships between these entities is provided in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information (SI). Enterprise agents can be aggregated into a collective referred to as an “enterprise.” The parameters of an enterprise agent include identification number, industry type, enterprise type, latitude, longitude, initial annual production, production decline rate, initial energy intensity, clean energy share, annual energy consumption, and other relevant factors. The variables for the different entities in the model are detailed in Table S1 of the SI. For the time scale, the model operates with a time step of one month, with a cycle of one year, and a total runtime period set to 40 years, from 2020 to 2060. The spatial scale is not considered in this study, assuming that transactions between firms are not affected by geographic location.

Process overview

The model operation process primarily includes initialization settings, initial quota issuance, enterprise production, trading, index calculation, and data output, as illustrated in Figure S2. The initialization setup is used to establish the model, create the simulation environment, and set parameters. Initial quota issuance, enterprise production, and trading are the main components, which will be described in detail later. Index calculation and data output are used to compute evaluation metrics, generate charts, and export running data. As time progresses, the initial quota issuance, enterprise production activities, and market trading processes continuously evolve, leading to fluctuations in energy consumption, carbon emissions, trading prices, and trading volumes for each enterprise, thereby reflecting the model’s dynamic evolution.

Design concept

The model design concept aims to outline the key features of a simulation model for the market-oriented allocation of energy-consuming rights using ABM. At the agent level, the model incorporates mechanisms such as perception, learning, adaptation, and interaction, while at the system level, it addresses complex phenomena including emergence, prediction, and stochasticity. This section also describes other essential elements of the model, including the fundamental principles of modeling, ensembles, and observations. The flexibility of ABM allows for scenario analysis to explore the impact of various factors on overall system behavior. Sensitivity analysis is used to identify key factors and parameters that influence system dynamics.

Specifically, during market operations, enterprises dynamically adjust their quota transactions based on production requirements and technological advancement status. They obtain critical market data such as pricing trends and regulatory policies directly from trading platforms. Using this information, companies assess their energy consumption patterns to decide on market participation, while tailoring bidding strategies to align with current market prices and their individual risk profiles. This process enables them to develop data-driven trading decisions. Post-transaction, firms analyze outcomes including quota acquisition or sales performance and compliance records, using these insights to strategically modify subsequent production plans, technology upgrade roadmaps, and future trading approaches. A detailed explanation of each design concept is provided in Table 2.

Details

Initialization settings

In the initial state of the model world, initial conditions are defined, agents are created, and initial parameters are imported based on the basic information database of the enterprise.

Initial quota issuance

In the ECRT market, the government has two methods for issuing quotas: free allocation and paid allocation. Within the free allocation category, the two primary methods are the historical aggregate method and the production baseline method. The historical aggregate method determines the quota quantity for the current year based on the enterprise’s historical energy consumption. In contrast, the production baseline method issues the quota quantity for the current year based on the energy consumption levels of unit products in the cement industry and other relevant factors. The model takes both allocation methods into account:

(1) Historical aggregate method

The quota allocation function for the historical aggregate method is as follows:

where Q denotes the initial amount of quota received by the enterprise free of charge, \(\:{E}_{average}\:\)indicates the average amount of energy used by the enterprise over a three-year period, with \(\:{E}_{t-3}\), \(\:{E}_{t-2}\), and \(\:{E}_{t-1}\) representing the total energy consumption of the enterprise three years ago, two years ago and one year ago, respectively. Here, \(\:\mu\:\) indicates the enterprise energy consumption reduction coefficient, \(\:\phi\:\) indicates the enterprise performance factor, \(\:\omega\:\) indicates the percentage of free issuance, and \(\:\varphi\:\) indicates the regulation coefficient.

The enterprise performance factor \(\:\phi\:\) is determined as follows:

If an enterprise purchases a quota:

When \(\:E-QS\le\:QEC\), then the enterprise performs well.

When \(\:E-QS>QEC\), the enterprise has failed to perform.

Where E denotes the amount of energy used by enterprises, QS denotes the amount of quotas actually purchased by enterprises in the primary market, and QEC denotes the amount of quotas actually purchased by enterprises in the secondary market.

If an enterprise sells a quota, it is obligated to fulfill its commitments regardless of whether the quota has been successfully sold.

The regulation coefficient \(\:\varphi\:\) ensures that the total amount of quotas issued to enterprises is less than the total energy consumption control target. This is determined as follows:

If \(\:{CE}_{total}-\sum\:Q\ge\:0\), the regulation coefficient defaults to 1.

If \(\:{CE}_{total}-\sum\:Q<0\), the regulation coefficient decreases by 5%. The initial quota issued to enterprises is then recalculated, and the relationship between the total energy consumption control index of the regional industry and the initial quota for all enterprises is determined. This cycle continues until \(\:{CE}_{total}-\sum\:Q\ge\:0\), at which point the value of the regulation coefficient is established.

Here, \(\:{CE}_{total}\) indicates the total regional sectoral energy consumption control target, and \(\:\sum\:Q\) represents the initial quota for all enterprises.

The total energy consumption control indicators for regional high-energy-consuming industries are calculated as follows:

where \(\:{CE}_{total,0}\) represents the total regional sectoral energy consumption control target for the initial year. \(\:{CE}_{total,\text{t}}\) and \(\:{CE}_{total,\text{t}-1}\) denote the total regional sectoral energy consumption control targets for years t and t-1, respectively. \(\:{AE}_{total,0}\) indicates the total regional energy consumption control target for the initial year, while \(\:{AE}_{average}\) represents the three-year average of total energy consumption control targets for the region. The term \(\:{AE}_{total,t-3}+{AE}_{total,t-2}+{AE}_{total,t-1}\)indicates total regional energy consumption three years ago, two years ago and one year ago, respectively. Here, \(\:\gamma\:\) indicates the proportion of total energy consumption in energy-using industries to total energy consumption in the region, \(\:\delta\:\) denotes the coefficient of decline of total energy consumption in energy-using industries, and \(\:\beta\:\) denotes the coefficient of growth of total regional energy consumption.

(2) Production baseline method

The quota allocation function for the production baseline method is defined as follows:

where \(\:Q\) denotes the initial amount of quota received by the enterprise free of charge, \(\:Y\) denotes the annual production output of the enterprise, \(\:\epsilon\:\) denotes the baseline value of energy consumption per unit of product in the energy-using industry, \(\:\mu\:\) indicates enterprise energy consumption reduction coefficient, \(\:\phi\:\) indicates the enterprise performance factor, \(\:\omega\:\) indicates the percentage of free issuance, and \(\:\varphi\:\) indicates the regulation coefficient.

In addition to the free issuance of quotas, the model also simulates the paid issuance of initial quotas. This process is primarily conducted by the government through an auction of quotas. In determining the proportion of payment for quotas, the model simulates two methods, namely, the annual decreasing method, which decreases linearly from year to year, and the stepped decreasing method, which decreases by a certain percentage in 10-year intervals. The paid auction method for this model is explained in further detail below.

Suppose there are r enterprises, with one auction round per year, and that w enterprises succeed in purchasing a quota (\(\:w\le\:r\)) each year. The bid price generated by enterprise i in year t is denoted as \(\:{p}_{i,t}^{c}\), the corresponding bid volume is \(\:{q}_{i,t}^{c}\), and the bid price \(\:{p}_{i,t}^{c}\) follows a uniform distribution \(\:U(c,d)\):

where \(\:{c}_{t}\) denotes the government minimum guide price in year t, \(\:{d}_{t}\) denotes the highest price traded in the primary market in year t, and \(\:e{p}_{t}\) denotes the equilibrium price in year t.

The initial quota quantity function used by the government for the auction each year is defined as follows:

where \(\:{Toppermit}_{1}\) denotes the initial amount of allowances used by the Government for the auction in the case of the historical aggregates approach, \(\:{Q}_{i,{t}_{1}}^{c}\) denotes the amount of bids received from enterprises in the case of the historical aggregates approach. \(\:{Toppermit}_{2}\) denotes the initial amount of allowances used by the Government for the auction in the case of the baseline production approach, and \(\:{Q}_{i,{t}_{2}}^{c}\) denotes the amount of bids received from enterprises in the case of the baseline production approach.

In the model, enterprises are categorized into two types: risk-averse and risk-avoidant. Risk-avoidant enterprises purchase quotas in the primary market in an amount equal to their own needs, while risk-avoidant enterprises purchase quotas in the primary market in an amount equal to twice their actual needs.

The primary energy rights auction market operates on a uniform price-sealed bidding mechanism. After all enterprises have submitted their bidding combinations, which include bidding prices and quantities, the Government ranks these bids from highest to lowest. The corresponding quotas are then sold in this order, represented as (\(\:{p}_{i,t,1}^{c},{q}_{i,t,1}^{c}\)),(\(\:{p}_{i,t,2}^{c},{q}_{i,t,2}^{c}\)),(\(\:{p}_{i,t,3}^{c},{q}_{i,t,3}^{c}\))… (\(\:{p}_{i,t,r}^{c},{q}_{i,t,r}^{c}\)). If multiple enterprises submit bids at the same price, the one with more bids is prioritized in the queue to purchase quotas.

The functional relationship between the amount of quota actually purchased by an enterprise in the primary market is defined as follows:

where \(\:QS\) denotes the amount actually purchased by the enterprise in the primary market and \(\:{q}_{i,t}^{c}\) denotes the amount expected to be purchased by the enterprise in the primary market.

Enterprise Production The functional equation for the energy used in the production of the enterprise is defined as follows:

where E denotes the amount of energy used by the enterprise, Y denotes the annual production output of the enterprise, and I denotes the energy intensity of the enterprise.

The formula for the production decline rate function of the enterprise is as follows:

where Y denotes the annual output of the enterprise’s production and \(\:\theta\:\) denotes the enterprise’s production decline rate, which defaults to 3%. When an enterprise purchases quotas in the previous year, if the amount purchased exceeds 10% of the enterprise’s own energy use, the production decline factor increases to 5%. If the amount of quotas sold exceeds 50% of its own energy use, the production decline rate for the next year becomes 0.01. If the enterprise’s production decline exceeds 90% of its initial production, the enterprise will close down and exit the market.

The equation for the decrease in the change in energy intensity is as follows:

where I denotes the energy intensity of the enterprise, and \(\:\lambda\:\) denotes the coefficient of reduction of energy intensity. If an enterprise purchases quotas for three consecutive years, and the amount of quotas purchased exceeds 10% of its own energy consumption, then the enterprise’s energy intensity decreases, with a minimum energy intensity of not less than 0.09 tce per ton.

The formula for increasing the share of clean energy is as follows:

where \(\:{CEP}_{t}\) denotes the clean energy share of the enterprise in year t, and \(\:\kappa\:\) denotes the coefficient of increase in the clean energy share of the enterprise, with the maximum clean energy share of the enterprise not exceeding 70%.

Transactions. Suppose there are m buyers who wish to purchase quantity \(\:{Q}_{i}^{c}\) at an offer price \(\:{P}_{i}^{c}\). Of these buyers, x enterprises succeed in purchasing quotas (where x\(\:\le\:m\)). There are also n sellers who offer quota quantities \(\:{P}_{j}^{s}\) and sell quantity \(\:{Q}_{j}^{s}\), of which y enterprises succeed in selling quotas (where y\(\:\le\:n\)). The offers from both sides satisfy a uniform distribution \(\:U(a,b)\). The minimum government guideline price and the highest price traded in the secondary market are defined as follows:

where \(\:{a}_{t}\) is the minimum government guideline price, \(\:{b}_{t}\) is the highest price traded, and \(\:E{P}_{t-1}\) is the equilibrium price traded in the secondary market.

The functional relationship between the amount of quotas expected to be bought and sold by enterprises in the secondary market is given by the following equations:

where \(\:{Q}_{i}^{c}\) is the amount the enterprise is expected to buy, \(\:{Q}_{j}^{s}\) is the amount the enterprise is expected to sell, \(\:Q\) is the amount of initial quota the enterprise receives, and E is the amount of energy used by the enterprise.

Total supply as a function of total demand in the secondary market is expressed as follows:

where \(\:QCS\) denotes total secondary market supply, and \(\:QCD\) denotes total secondary market demand.

The buyers’ prices are sorted from high to low: (\(\:{P}_{i,1}^{c},{Q}_{i,1}^{c}\)), (\(\:{P}_{i,2}^{c},{Q}_{i,2}^{c}\)), (\(\:{P}_{i,3}^{c},{Q}_{i,3}^{c}\)), …, (\(\:{P}_{i,m}^{c},{Q}_{i,m}^{c}\)). The sellers’ prices are sorted from low to high: (\(\:{P}_{j,1}^{s},{Q}_{j,1}^{s}\)), (\(\:{P}_{j,2}^{s},{Q}_{j,2}^{s}\)), (\(\:{P}_{j,3}^{s},{Q}_{j,3}^{s}\)), …, (\(\:{P}_{j,n}^{s},{Q}_{j,n}^{s}\)). The bidding principle states that the enterprise with the lowest bid has the priority to sell its quotas, while the enterprise with the highest bid has the priority to buy.

(1) Supply exceeds demand in the market.

When supply exceeds demand in the market, it creates a buyer’s market. In this scenario, the buyer’s demand is fully satisfied, meaning that buyers can purchase quotas. At this time, the total number of buyer transactions is denoted as QCD, and the sellers’ prices are ranked from low to high, prioritizing the seller with the lowest price to sell their quotas. The equilibrium price in the market at this point is given by:

where EP denotes the equilibrium price in the market, \(\:{P}_{j}^{s}\) is the seller’s selling price, and \(\:{Q}_{j}^{s}\) is the quantity sold.

The functional relationship between the amount of quotas actually purchased and sold by enterprises in the market is outlined below:

If an enterprise purchases a quota, the quantity purchased is given by:

If an enterprise sells a quota and the bidding is successful, the quantity sold is expressed as:

The total quantity sold by the last enterprise with a successful bid is represented as:

If the bidding is unsuccessful, the actual purchase will be zero.

where QEC denotes the actual quantity purchased by an enterprise in the secondary market, QES denotes the actual quantity sold by an enterprise in the secondary market, and\(\:\:QE{S}_{y}\) denotes the actual quantity sold by the last enterprise with a successful bid.

(2) Less supply than demand in the market

When supply is less than demand in the market, it creates a seller’s market. In this scenario, it is assumed that all sellers are satisfied and can sell their quotas. At this time, the total number of seller transactions is denoted as QCS, and buyers are ranked from highest to lowest price, with the buyer offering the highest price given priority to purchase quotas. The equilibrium price in the market at this time is expressed as:

where EP denotes the equilibrium price in the market, \(\:{P}_{i}^{c}\) is the buyer’s purchase price, and \(\:{Q}_{i}^{c}\) is the quantity purchased.

The functional relationship between the amount of quotas actually purchased and sold by enterprises in the market is given below:

If an enterprise purchases a quota and the bidding is successful, the quantity purchased is given by:

If the bidding is unsuccessful, the actual purchase will be zero.

If the enterprise sells the quota, the quantity sold is expressed as:

where QEC denotes the actual quantity purchased by an enterprise in the secondary market, \(\:QE{C}_{x}\) denotes the actual quantity purchased by the last enterprise with a successful bid, and QES denotes the actual quantity sold by an enterprise in the secondary market.

Indicators. This model assesses the development of the ECRT market through various indicators, including total regional energy consumption, average regional energy intensity, regional carbon emissions, market transaction volume, transaction price, and transaction amount. Some of the indicators are calculated as follows:

where \(\:EA\) is the total regional energy use, IA is the average regional energy intensity, \(\:{E}_{c{o}_{2}}\) is the carbon emissions of the enterprise, \(\:{E}_{combustibility}\) is the CO2 emissions from the fossil fuel combustion activities of the enterprise, \(\:{E}_{process}\) is the CO2 emissions generated by the enterprise in the production process, and \(\:{E}_{electricity\:and\:heat}\) is the CO2 emissions corresponding to the net purchases of electricity and heat by the enterprise.

The modeler can monitor and control the operation of the simulation model by observing changes in these metrics and continuously improving it. Specifically, parameters will be adjusted based on observed declines in total energy and carbon emissions to ensure realistic reductions. Market trading volumes will also guide quota allocation adjustments. If trading activity is low, the quota distribution method or free allocation ratio can be modified to stimulate market participation. In cases of abnormal conditions - such as zero trading volume - the causes will be promptly analyzed, followed by parameter adjustments.

Data Output. The result output submodel primarily serves to display the simulation outcomes, exporting all forecast results related to total regional energy consumption, energy intensity, carbon emissions, trading volume, and other indicators. This enables further analysis of the forecast results in subsequent steps.

Materials and data

The cement industry is a critical sector in China, both in terms of energy consumption and carbon emissions. It is characterized by high energy dependence and significant carbon emissions during the production process. As such, controlling carbon emissions in the cement industry has become a key priority for China in achieving its “dual carbon” goals. Shandong Province, as a major base for cement production in China, hosts numerous large-scale cement enterprises and boasts a relatively mature industrial chain. Therefore, this study focuses on the cement industry in Shandong Province as a case study, using it to validate the feasibility of the model by simulating the ECRT of enterprises within this sector.

Based on government statistics and field investigations of 12 cement enterprises, we collected energy consumption data for these firms from 2020 to 2023. The enterprises were classified into four categories according to their energy consumption levels: Advanced level, Benchmark level, Baseline level, and Below baseline level, with a ratio of approximately 1:2:2:1 for each respective group. The study uses 2020 as the base year for enterprise data to align with the start of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan and the implementation of stricter energy control policies. Data from 2021 to 2023 were used to parameterize changes in production levels, energy intensity, and shares of clean energy for the enterprises. The model simulates a total of 60 representative cement enterprises, reflecting the number and geographic distribution of cement companies within Shandong Province. Additionally, the attributes of enterprises in the trading market were classified into two categories: risk-preferring and risk-averse. Parameters such as initial production levels, clean energy shares, and other enterprise-specific characteristics were set within defined data ranges. The basic data for these enterprises are provided in Table S2 of the SI.

The coefficients used in the model primarily include factors such as enterprise energy consumption reduction rates, energy intensity reduction rates, and production reduction rates. These coefficients were derived from sources such as the 14th Five-Year Plans of provinces and municipalities, relevant policy documents, and forecasts. Details of the coefficient settings are provided in Table S3 of the SI.

Scenario settings

This model establishes two types of scenario comparisons and a total of seven sub-scenarios. The study is based on relevant policy documents from pilot provinces, utilizing the production baseline method for assessment in the cement industry. By comparing different sub-scenarios, the mechanism of market-oriented allocation of energy consumption rights is analyzed, and the optimal path for achieving resource efficiency in ECRT is explored.

Quota distribution scenarios

The Quota Distribution Scenarios simulate different methods of initial quota issuance, comprising four sub-scenarios: No Market scenario (S0); Free Quota scenario (S1); Paid Quota scenario (S2); and Tiered Payment scenario (S3). By comparing S0, S1, S2, and S3, the study examines the impacts of the presence or absence of a trading market, as well as the effects of different issuance methods (free vs. paid) on the market operation mechanism. Furthermore, it explores how initial quota issuance methods influence regional energy consumption and carbon emissions.

Development model scenarios

The Development Model Scenarios simulate varying levels of government control and include three sub-scenarios: Baseline Development scenario (S4); Traditional Development scenario (S5); and High-quality Development scenario (S6). By comparing S4, S5, and S6, the study evaluates the impacts of different development models on regional energy consumption, carbon emissions, and market activity. These comparisons provide insights into how varying government control efforts influence the effectiveness of the ECRT mechanism.

The specific settings for each sub-scenario are detailed in Table 3.

Results and discussions

Simulating different initial quota issuances

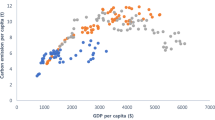

As shown in Fig. 2, the No Market scenario (S0) significantly underperforms compared to the Paid Quota scenario (S2) in terms of energy consumption and carbon emissions (Figs. 2(a) and 2(c)). Under S2, total energy consumption decreases by 78.5%, while carbon emissions decline by 80.2% (see Table S4). In contrast, the reductions in S0 are only 70.4% for both metrics. This additional reduction of 8.1% in energy consumption and 9.8% in carbon emissions under the trading market scenario underscores the effectiveness of establishing an ECRT market in enhancing regional energy and carbon reduction efforts, thereby supporting the cement industry in achieving its carbon neutrality goals. The trends in energy intensity further highlight the effectiveness of the market mechanism (Fig. 2(b)). In S0, energy intensity remains constant at 0.1087 tce/ton. However, under the S2 scenario, energy intensity declines steadily, reaching 0.1039 tce/ton by 2060. Notably, the decline begins three years after the market is launched, indicating that the ECRT mechanism incentivizes enterprises to optimize production processes, adopt cleaner technologies, and reduce energy consumption intensity. Among all scenarios, S2 exhibits the fastest decline in energy intensity, particularly before 2040, after which the trend stabilizes, reflecting the long-term impact of the market mechanism on improving energy efficiency.

A comparison between the S1 (free allocation) and S2 (paid allocation) scenarios reveals that S2 achieves 7.9% more energy savings and 6.8% greater carbon emission reductions, with a faster decline in energy intensity (Figs. 2(b) and 2(c)). This indicates that the paid allocation mechanism is more effective in phasing out outdated production processes and equipment, thereby improving energy efficiency. Similarly, a comparison between S2 and S3 (tiered payment) shows that S2 achieves 2.4% more energy savings and 2.2% lower emissions, with a lower energy intensity. These findings suggest that the annual regressive payment method in S2 is more conducive to energy savings, carbon reductions, and efficiency improvements than the tiered payment method in S3, which may lead to concentrated trading activities around payment deadlines, causing market fluctuations.

The trading market’s activity is particularly prominent in the S2 scenario. As shown in Figs. 2(d) and 2(f), trading volume and transaction amounts in S2 peak between 2035 and 2040, with the highest trading volume of 171 kilo tce in 2036 and the maximum transaction amount of 167 million yuan in 2040. This period represents the most active phase of the market, suggesting that policymakers could optimize market rules during this critical period to further enhance market efficiency. In contrast, the trading volume and transaction amounts in S1 are significantly lower and grow more slowly, reflecting the limited impact of the free allocation mechanism on market activity. Meanwhile, the tiered payment mechanism in S3 results in a step-like pattern in trading volume and transaction amounts, indicating that phased payment ratios significantly influence trading behavior.

The trends in trading prices further reveal the dynamics of supply and demand in the market (Fig. 2(e)). In the S2 and S3 scenarios, prices fluctuate within the range of 500–1400 yuan/ton and gradually stabilize, reflecting a dynamic balance between supply and demand. This stability allows enterprises to better plan their production and trading activities. In contrast, the S1 scenario shows a continuous upward trend in prices, indicating persistent supply shortages. This suggests that the free allocation mechanism leads to insufficient quota supply, forcing enterprises to purchase quotas to meet production needs, thereby limiting market efficiency.

In summary, the S2 paid allocation scenario demonstrates the greatest potential for reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions, improving energy efficiency, and enhancing market activity, which is consistent with the empirical analyses reported by previous studies26,28. The annual regressive payment method in S2 not only drives significant energy savings and carbon reductions but also accelerates technological upgrades and optimizes resource allocation. In comparison, the free allocation mechanism (S1) and the tiered payment mechanism (S3) show limitations in market efficiency and emission reduction effectiveness. These findings underscore the importance of designing effective market mechanisms to optimize resource allocation and promote sustainable development in the cement industry.

Simulating different government control efforts

As shown in Fig. 3, a comparison of the Baseline (S4), Traditional Development (S5), and High-Quality Development (S6) scenarios reveals a general downward trend in both total energy consumption and total carbon emissions. While the differences in total energy consumption among these scenarios are not significant (Fig. 3(a)), carbon emissions decrease most rapidly in the S6 scenario and slowest in the S5 scenario (Fig. 3(c)). This highlights the effectiveness of high-quality development policies in encouraging enterprises to adopt carbon reduction measures, which align with the broader goals of the “dual-carbon” strategy. On the other hand, the slower decline in carbon emissions under the S5 scenario reflects the challenges of balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability.

By 2060, the energy intensity in the S5 scenario remains unchanged (Fig. 3(b)), indicating that enterprises under this scenario prioritize economic growth over environmental concerns. This lack of improvement in energy efficiency suggests low resource utilization and outdated production processes. In contrast, the S4 and S6 scenarios show a downward trend in energy consumption intensity, with the S6 scenario achieving slightly better results. Enterprises in the S6 scenario appear to pay more attention to process-level improvements, though the overall gains in energy efficiency remain modest. These findings emphasize the need for policies that encourage enterprises to adopt cleaner technologies and improve resource efficiency, especially in scenarios where economic growth dominates decision-making.

The trading market dynamics under the S4, S5, and S6 scenarios reveal distinct patterns. Market trading volumes initially increase before declining (Fig. 3(d)), with the S5 scenario showing the highest overall trading activity. This reflects the strong economic incentives driving market participation in the traditional development scenario. Meanwhile, the peak trading volume in the S6 scenario reaches 177 kilo tce in 2034, demonstrating that even under high-quality development policies, market activity remains significant. Transaction prices fluctuate between 500 and 1000 yuan (Fig. 3(e)), with the S5 scenario showing slightly higher prices, indicating stronger demand for quotas. Transaction amounts follow a similar trend, peaking in the S4 scenario in 2037 at 151 million yuan (Fig. 3(f)). These variations in market behavior suggest that while economic incentives can stimulate trading activity, they must be paired with mechanisms to ensure environmental accountability.

In conclusion, the S6 scenario stands out for its ability to reduce carbon emissions effectively, while S5 achieves the highest market activity due to strong economic incentives. However, the environmental trade-offs in S5 highlight the importance of integrating stricter regulations to prevent enterprises from prioritizing profits over sustainability. These results underline the critical role of balanced policies in achieving both economic and environmental objectives.

Sensitivity analysis

Due to limited market activity in ECRT pilot areas, obtaining sufficient real transaction data remains challenging. To address this constraint and enhance model validity, we conduct sensitivity analysis on three key parameters: (1) enterprise production decline rate, (2) energy consumption reduction coefficient, and (3) baseline energy intensity. Unlike conventional regression analyses that rely on historical data patterns14, our approach identifies critical parameter thresholds by systematically examining their impacts on energy consumption, trading volume, and price dynamics. This enables more robust policy insights despite data limitations.

(1) Enterprise production decline rate.

The variation range of the model parameters is set between 0.01 and 0.05, with a step size of 0.01. The system’s changes are evaluated using indicators such as total energy consumption, trading volume, and trading price. As illustrated in Fig. 4(a), by 2060, total energy consumption is 1.2 million tce when the parameters are set to 0.01, compared to 0.3 million tce at 0.05. This significant difference indicates that the production decline rate substantially impacts the energy consumption levels of enterprises, highlighting the importance of parameter selection on the results.

In Figs. 4(b) and 4(c), varying parameter values lead to notable fluctuations in trading prices, which subsequently affect the supply and demand dynamics in the market. When the parameters are set to 0.01 and 0.02, the market experiences a supply shortage, resulting in a high demand for quotas as enterprises urgently seek to purchase them to meet production needs, thus increasing trading volume. Conversely, with parameters at 0.04 and 0.05, the market shifts to a supply surplus, causing prices to drop as most enterprises hold excess quotas, leading to a decrease in trading volume. When the parameter is set to 0.03, the market demonstrates relative stability, indicating this as the optimal choice for balancing supply and demand.

(2) Enterprise energy consumption reduction coefficient

The variation range of the model parameters is set from 0.01 to 0.2, with a step size of 0.05. The simulation results are presented in Fig. 5. The findings indicate that when the parameters are set to 0.15 and 0.2, enterprises receive fewer free quotas, leading to a supply surplus in the market during the early stages of model operation. Consequently, many enterprises encounter difficulties in purchasing quotas, resulting in contract failures, a low market trading volume, and a rapid increase in trading prices. In contrast, when the parameters are set to 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1, the market demonstrates relatively stable development, characterized by minor fluctuations in transaction prices and a dynamic balance between supply and demand. Notably, when the parameter is set to 0.1, the trading price is slightly elevated, reflecting the scarcity of ECRT indicators. Therefore, selecting a parameter of 0.1 is more conducive to market development.

(3) Baseline energy intensity

The range of parameter changes is set from 0.1 to 0.117, with values of 0.1, 0.107, and 0.117 selected for analysis, as shown in Fig. 6. As the parameter increases, the market trading volume gradually rises, while the trading price tends to stabilize. However, smaller changes in the parameter can lead to larger fluctuations in the market. When the parameter is set at 0.1 and 0.107, the initial quotas obtained by enterprises are insufficient, resulting in most companies needing to purchase quotas in the early stages. This situation drives up trading prices, indicating that the parameter is set too aggressively, which adversely affects enterprise performance and hinders the stable development of the market. In contrast, a parameter of 0.117 is more reasonably designed, having a moderate impact on enterprises, stable trading prices, and high market activity.

Conclusion and implications

This study employs an ABM approach to comprehensively analyze the ECRT system within the cement industry of Shandong Province. The findings indicate that the implementation of ECRT significantly enhances energy efficiency and improves environmental performance, with total energy consumption and carbon emission intensity reduced by 8.1% and 9.8%, respectively. Additionally, the use of paid quota allocation proves to be more effective than free quota allocation, achieving 7.9% higher energy savings and 6.8% greater reductions in carbon emissions. Paid quotas also stabilize market trading prices, fostering greater enterprise participation in energy trading. Under the high-quality development scenario, energy efficiency improves by 4.4%, and carbon emissions decrease by 5%, aligning closely with China’s dual-carbon goals and demonstrating the effectiveness of policies promoting high-quality development.

These insights hold significant implications for policymakers and industry practitioners. Firstly, policy design should focus on establishing robust market mechanisms, particularly through paid quota systems, to enhance participation and efficiency in the ECRT market. Encouraging broader enterprise engagement in ECRT can be achieved by increasing awareness of trading benefits and simplifying compliance processes, thereby expanding market coverage. Furthermore, integrating ECRT with existing carbon trading systems can optimize resource allocation and enhance overall market vitality and environmental governance. Future research should aim to validate the model with empirical data and explore the application of ECRT in other energy-intensive industries, providing more comprehensive policy recommendations to support sustainable development goals.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Allen, M. R. et al. Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne[J/OL]. Nature 458 (7242), 1163–1166. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08019 (2009).

Drouet, L. et al. Net zero-emission pathways reduce the physical and economic risks of climate change[J/OL]. Nat. Clim. Change. 11 (12), 1070–1076. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01218-z (2021).

Zhao, X. et al. Challenges toward carbon neutrality in China: Strategies and countermeasures[J/OL]. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 176(June 2021): 105959. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105959

He, J. et al. Towards carbon neutrality: A study on china’s long-term low-carbon transition pathways and strategies[J/OL]. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology. 9, 100134 (2022). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666498421000582

Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council. Opinions on accelerating the construction of a National unified Market[EB/OL]. Xinhua Net. (2022). https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-04/10/content_5684385.htm

Wang, J., Li, Z. & Wang, Y. How does china’s energy-consumption trading policy affect the carbon abatement costs? An analysis based on Spatial difference-in-differences method[J/OL]. Energy 294, 130705 (2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360544224004778

Zhou, C., Li, Y. & Wu, C. Can the energy-consuming right transaction system improve energy efficiency of enterprises? New insights from China[J/OL]. Energ. Effi. 17 (5), 51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-024-10232-x (2024).

Zhang, J. X. & Hao, Z. Exploring the path of constructing china’s energy saving transaction mechanism[J]. Environ. Prot. 42 (01), 47–48 (2014).

Coase, R. H. The problem of social cost[J]. J. Law Econ. 3, 1–44 (1960).

Dales, J. Pollution, Property and Prices: An Essay in Policy-making and Economics (Edward Elgar Publishing, 1968).

Carlson, C. et al. Sulfur Dioxide Control by Electric Utilities: What Are the Gains from Trade?[J]. Discussion Papers, (2000).

Yang, S. et al. Impact of china’s carbon emissions trading scheme on firm-level pollution abatement and employment: evidence from a National panel dataset[J/OL]. Energy Econ. 136 (June), 107744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107744 (2024).

Jia, L. et al. Impact of carbon emission trading system on green technology innovation of energy enterprises in China[J/OL]. J. Environ. Manage. 360 (April), 121229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121229 (2024).

Feng, X., Zhao, Y. & Yan, R. Does carbon emission trading policy has emission reduction effect?—An empirical study based on quasi-natural experiment method[J/OL]. J. Environ. Manage. 351 (200), 119791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119791 (2024).

Aldrich, E. L. & Koerner, C. L. White certificate trading: A dying concept or just making its debut? Part I: market status and trends[J/OL]. Electricity J. 31 (3), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2018.03.002 (2018).

Duzgun, B. & Komurgoz, G. Turkey’s energy efficiency assessment: white certificates systems and their applicability in Turkey[J/OL]. Energy Policy. 65 (2014), 465–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.10.036 (2014).

Franzò, S. et al. A multi-stakeholder analysis of the economic efficiency of industrial energy efficiency policies: Empirical evidence from ten years of the Italian White Certificate Scheme[J/OL]. Applied Energy, 240(September 2018): 424–435. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.02.047

Safarzadeh, S., Hafezalkotob, A. & Jafari, H. Energy supply chain empowerment through tradable green and white certificates: A pathway to sustainable energy generation[J/OL]. Appl. Energy. 323 (June), 119601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119601 (2022).

Zheng, J., Zhang, W. & Wang, J. P. Review of research on energy saving transaction mechanisms[J]. Sci. Technol. Manage. Res. 35 (07), 209–213 (2015).

Ye, W. P. & Wang, Y. On the legal attributes of energy-consuming rights under the dual-carbon objective.[J]. J. Social Sci. Hunan Normal Univ. 51 (05), 86–95 (2022).

Li, X. Z. & Wang, H. On the legal attributes of energy-consuming rights[J]. Guangxi Social Sci. 3, 89–93 (2018).

Deng, H. F. & Chen, Y. D. Analysis of the attributes of energy-consuming rights in the context of the dual-carbon objective[J]. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 32(04), 66–72 (2022).

Gomes, E. G. & Lins, M. P. E. Modelling undesirable outputs with zero sum gains data envelopment analysis models[J/OL]. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 59 (5), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602384 (2008).

Yang, M. et al. Constructing energy-consuming right trading system for china’s manufacturing industry in 2025[J/OL]. Energy Policy. 144 (May), 111602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111602 (2020).

Zheng, Q., Hu, H. & Li, J. Enterprise decision-making in energy use rights trading market: A theoretical and simulation study[J/OL]. Energy Policy. 193 (August), 114278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114278 (2024).

Cui, H. & Cao, Y. Energy rights trading policy, Spatial spillovers, and energy utilization performance: evidence from Chinese cities[J/OL]. Energy Policy. 192 (May), 114234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114234 (2024).

Wang, K., Su, X. & Wang, S. How does the energy-consuming rights trading policy affect china’s carbon emission intensity?[J/OL]. Energy 276, 127579 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127579

Cheng, Z., Ding, C. J. & Zhao, K. Energy use rights trading and carbon emissions[J/OL]. Energy 315, 134360 (2025). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360544225000027

Shen, H., Xiong, P. & Zhou, L. The impact of the energy-consuming right trading system on corporate environmental performance: based on empirical evidence from panel data of industrial enterprises listed in pilot regions[J/OL]. Heliyon 10 (8), e29628 (2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844024056597

Grimm, V. et al. The ODD protocol for describing agent-based and other simulation models: A second update to improve clarity, replication, and structural realism[J/OL]. JASSS 23 (2). https://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.4259 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Key R&D Program (Soft Science Project) of Shandong Province [2024RKY0404], the Humanities and Social Science Project of the Ministry of Education of China [24YJCZH081], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [42471317] and the Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province [tsqn202312232].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. H.: Conceptualization, Writing-Review, Project administration, and Funding acquisition. X. L.: Data curation, Methodology, and Writing- original draft. X.H. B., J. G. and Z.H. C.: Data curation and Software. D. Y. and F. S.: Methodology, and Writing- original draft. Y.F. J.: Editing and Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, F., Li, X., Bi, X. et al. Agent based modeling of energy consuming rights trading for low carbon transformation in China. Sci Rep 15, 24754 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10838-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10838-w