Abstract

A highly efficient magnetic nanocatalyst has been developed by covalently grafting a Pd(0)-Sb@A complex onto a silica-coated nickel ferrite support. This innovative nanocatalyst has been thoroughly analyzed using various techniques, including FT-IR, VSM, XRD, ICP, EDX, XPS, TEM, and FE-SEM. Its performance was then evaluated in the synthesis of symmetrical sulfides and unsymmetrical ether derivatives. Key advantages of this approach include high product yields, reduced reaction times, straightforward synthesis, easy magnetic separation, and excellent catalyst recoverability, maintaining activity for at least four cycles without notable degradation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From contemporary viewpoints, synthetic chemistry has advanced to a highly sophisticated stage, making the isolation, purification, and reusability of chemicals crucial for promoting green and sustainable practices1,2,3. In homogeneous catalytic systems, isolating and reusing catalysts from reaction mixtures remains challenging and labor-intensive4,5. While heterogeneous systems partially address this issue, the effective removal of trace amounts of contaminated catalyst from synthesized products continues to be critical, especially in the pharmaceutical industry, where stringent hygiene regulations govern the elimination of even minute impurities6,7,8. Various purification techniques, including chromatography, centrifugation, distillation, filtration, and extraction, are employed extensively to tackle this challenge9. In the pursuit of simpler and more effective solutions, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have gained significant attention in catalytic applications, offering the advantage of easy isolation through the use of an external magnet10,11,12. The nanometric size of these materials provides a high surface area, facilitating surface modifications through external loading and enhancing catalytic activity13,14,15. Nano ferrites (MFe2O4) possess a significant number of hydroxyl groups on their surface, which can be utilized for covalent bonding with suitable organic linkers16,17. These secondary functional groups can, in turn, be leveraged to anchor an additional shell of metal nanoparticles, enabling them to act as active components in catalysis18. Such surface engineering, involving appropriate ligands or biomolecules, enhances the stability of the primary nanoparticles, reduces their tendency to aggregate, prevents oxidation, decreases their solubility in organic solvents, and acts as a mild reducing agent for incoming metal salts19,20. Among the heterogeneous catalysts, NiFe2O4 is widely utilized due to its magnetic retrievability and easy synthesis21,22. NiFe2O4 nanoparticles facilitate the support of various catalysts, allowing for their easy retrieval after multiple uses23,24. Magnetic nanoparticles, particularly NiFe2O4 coated with silica (SiO2@NiFe2O4), are gaining attention as promising supports for the immobilization of catalysts19,25,26,27. Magnetic separation of magnetic nanoparticles proves to be significantly more efficient than filtration or centrifugation16. This method is simple to execute, cost-effective, and shows great potential for use in industrial applications. Metal nanoparticles are crucial in several fields, especially in catalysis28. Numerous efforts have been made to develop suitable catalytic systems for achieving Pd-catalyzed C-S and C-O coupling reactions under heterogeneous conditions29. This is driven by the need to recover the expensive Pd metal and the industrial demand for products free from Pd contamination30,31. To address these requirements, various heterogeneous Pd catalyst systems have been introduced for C-S and C-O cross-coupling reactions31. However, many of these systems come with significant drawbacks, such as lengthy and cumbersome processing steps, high costs, and the complexity of catalyst synthesis32,33. Additionally, challenges like catalyst recyclability and the leaching of palladium a costly metal remain critical issues. Advancing highly efficient palladium-catalyzed systems alongside implementing sustainable and eco-friendly reaction conditions for these cross-coupling reactions continues to be a focal point of both academic and industrial research34,35,36.

This study aimed to explore the preparation and application of heterogeneous catalytic systems utilizing magnetic nanostructured catalysts for organic transformations. As part of our efforts, we successfully developed a novel, highly efficient, and magnetically separable catalyst by immobilizing Pd(0) onto Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4. This catalyst demonstrated excellent performance in C–S and C–O cross-coupling reactions.

Experimental

Materials

The essential materials required for synthesizing the nanocatalyst, coupling derivatives, reagents, and solvents, were procured from Merck, Fluka, and a range of other chemical suppliers.

Preparation of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4

For the synthesis of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 MNPs, first, SiO2@NiFe2O4 was synthesized by the co-precipitation method (Fig. 1)11,37,38. For the synthesis of the A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 complex, 2 g of the prepared SiO2@NiFe2O4 were dispersed in 25 ml of ethanol by sonication for 20 min. Subsequently, 3 mmol of 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid (A) were added to the reaction mixture and stirred for 23 h under reflux conditions. Following this, the resulting A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 was separated using a magnet, washed with distilled water and ethyl acetate, and then dried at 50 ℃. Next, 1 g of A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 was dispersed in 25 ml of MtOH and sonicated for 20 min. Then, 2.5 mmol of 2,3-hydroxybenzaldehyde were added to the mixture and stirred for 23 h. Afterward, the mixture was cooled, and the Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 nanoparticles were separated from the solution, washed with distilled water and ethyl acetate, and dried. Finally, to prepare Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4, a mixture of Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 (1.0 g), palladium (II) acetate (3 mmol), and 25 ml of ethanol was added into the flask and stirred at 60 ℃. An extra 1.5 mmol of NaBH4 was added to the reaction mixture, which was then stirred for 4 h. After the reaction finished, the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 catalyst was separated, thoroughly washed with distilled water and ethanol, and subsequently dried.

Preparation of C–S coupling reactions

In a flask, a mixture containing iodobenzene (1 mmol, 0.204 g), KOH (0.6 mmol, 0.033 g), and S8 (0.5 mmol, 0.128 g) with Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 catalyst (0.02 g) was dissolved in ethanol and stirred at 70 ℃. The progress of the reaction was monitored using TLC, and stirring continued until completion. Upon cooling, the catalyst was removed with a magnet. The product was extracted using a mixture of water and hexane. The organic layer was dried over 1.5 g of Na2SO4, and afterward, the solvent was evaporated. The pure product was then obtained through recrystallization from ethanol solvent (refer to Fig. 2).

Preparation of C-O coupling

A mixture composed of phenol (1.2 mmol, 0.112 g), iodobenzene (1 mmol, 0.204 g), and potassium hydroxide (1 mmol, 0.056 g) was prepared in the presence of the catalyst Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 (0.02 g) and dissolved in polyethylene glycol. The solution was then agitated at a temperature of 120 ℃ to facilitate the reaction. The progression of this reaction was monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Upon the completion of the reaction, an external magnet was employed to isolate the catalyst from the reaction mixture. Subsequent purification involved washing the resultant product with ethyl acetate and water. The organic phase was then dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. Following this, the organic solvent was evaporated, yielding the pure products, which are depicted in Fig. 3.

Catalyst characterizations

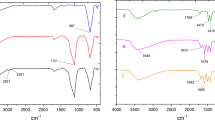

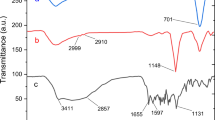

The successful functionalization of the NiFe2O4 MNPs is evident from the FTIR analysis shown in Fig. 4. The absorption bands for NiFe2O4 (Fig. 4a) and SiO2@NiFe2O4 (Fig. 4b) aligned with our previous findings, respectively39,40. The modification of SiO2@NiFe2O4 using 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid is validated by the aromatic ring stretching vibrations observed at 1511 and 1642 cm⁻1 (Fig. 4c). When 2,3-hydroxybenzaldehyde is added to the existing layer, characteristic peaks corresponding to imine functional groups are detected in the 1658 cm⁻1 region of the spectrum, indicating the formation of a new layer (Fig. 4d). Additionally, changes in intensity and shifts in the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 peaks confirm the coordination of the hydroxy atom with Pd (Fig. 4e).

Figure 5 presents the diffraction patterns of NiFe2O4 (Fig. 5a), and Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 (Fig. 5b). XRD analysis was performed to investigate the crystal structure of this material. The analysis identified six diffraction peaks corresponding to the inverse cubic spinel structure of NiFe2O4, observed at 2θ angles: 30.35° (220), 35.92° (311), 43.36° (400), 53.33° (422), 56.43° (511), and 64.12° (440). These values align closely with those reported in the literature, matching the JCPDS card 74–2081. This confirms that the crystal structure of the material remains intact after modification, as depicted in Fig. 5.

Figure 6 shows the TGA curves for SiO2@NiFe2O4MNPs, A@SiO2@NiFe2O4, and Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4. Figure 6a shows the TGA curve of NiFe2O4, indicating a single-step thermal decomposition. Below 250 °C, there was weight loss due to the removal of physically absorbed solvent. Meanwhile, in Fig. 6 b, the TGA curve of A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 reveals a two-step thermal decomposition. The initial weight loss observed below 250 °C is attributed to the removal of physically adsorbed solvent molecules. Following this, the second weight loss, occurring between 250 and 700 °C, is associated with the decomposition of organic groups (A) present on the catalyst’s surface. In examining Fig. 6c, the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve of the compound Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 reveals a 4% weight loss below 200 °C, indicative of the desorption process for physically adsorbed solvents. The major weight loss, approximately 40%, spanning from 200 to 600 °C, is attributed to the removal of organic components associated with NiFe2O4.

Furthermore, EDX serves as an outstanding resource for determining the elements within nanoparticles and evaluating their purity (Fig. 7). The EDX spectrum of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 MNPs illustrated in Fig. 7 confirms the presence of Fe, O, Ni, N, Si, Pd, and C in the catalyst.

In order to accurately evaluate the dimensions and appearance of the synthesized Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 (Fig. 8b and c) and NiFe2O4 (Fig. 8a) particles, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) technique was used. Analysis of the obtained SEM images showed that the final catalyst has a structure consisting of almost spherical (quasi-spherical) particles. The size of these particles is distributed in a relatively narrow range between 40 and 80 nm, which indicates relative uniformity in the synthesis process. Another noteworthy point is that SEM images indicated that the palladium complex did not undergo any significant degradation or structural change after immobilization on the nanostructured nickel ferrite substrate. This demonstrates the importance of using an appropriate immobilization method to preserve the catalytic properties of palladium (Fig. 8).

In Fig. 9, the XPS elemental survey scans, along with the Pd binding energy data, are provided for the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 catalyst. In Fig. 10a, the survey scan clearly shows peaks for elements such as C, O, Si, N, Ni, Fe, and Pd. To determine palladium’s oxidation state, XPS studies are depicted in Fig. 10 b, where the binding energy reveals two distinct peaks at 340 and 348 eV, corresponding to Pd [3d3/2] and [3d5/2], respectively. Additionally, peaks at 343 and 350 eV highlight the characteristic doublets due to the spin–orbit splitting of Pd [3d 5/2] and [3d 3/2] in its metallic form (Pd(0)).

Figure 10 shows a TEM image indicating that the magnetite particle size within the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 nanocatalyst is predominantly around 50 nm, with particles appearing uniform and well-dispersed. Additionally, a continuous layer of the (Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2) complex is visible on the surface of the nickel ferrite nanocatalyst, confirming the successful synthesis of the catalyst as demonstrated in the figure.

The leaching of palladium from Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 was investigated using ICP analysis and a hot filtration test. The ICP results showed that the palladium content in fresh and reused Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 was 2.3 × 10–4 and 2.2 × 10–4 mol. g−1, respectively. These findings suggest that the metal leaching from this catalyst is minimal.

The magnetic properties of NiFe2O4, shown in Fig. 11a, and Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4, depicted in Fig. 11 b, were examined using VSM techniques. As expected, the decrease in saturation magnetization, from about 45 emu/g to roughly 30 emu/g, can be attributed to the newly applied coating layer, as demonstrated in Fig. 11.

Catalytic studies

The study examined the catalytic performance of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 in the interaction between iodine and S8, serving as a representative system to identify the most favorable operating conditions. Various parameters, including nanocatalyst quantity, base type, solvent variation, and temperature, were scrutinized for their impact on the reaction outcome. The resulting product was isolated using EtOAc after the reaction concluded. Notably, the best response was observed in EtOH solvent at 70 ˚C with KOH as the base in the presence of 0.02 g of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 (Table 1).

Examining the optimized reaction conditions at hand, we investigated the C-S reaction of various aryl halides with S8. Our initial focus was on exploring the reaction with different substituted aryl halides containing NO2, NH2, and OMe. The findings suggest that the reaction can be completed within 20 to 120 min, delivering moderate to excellent results for aryl halides with either electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substitutions (as shown in Table 2).

The catalytic cycle proposed for synthesizing sulfides using the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 catalyst is illustrated in Fig. 12. The process begins with the reaction between an aryl halide and elemental sulfur (S8), where sulfur is believed to convert into disulfide ions (I) in a basic medium. These ions are quickly transformed into a more stable palladium disulfide species (intermediate II), facilitated by the action of the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 nanoparticles. Following this, an oxidative addition reaction between the aryl halide and intermediate II results in the generation of intermediate III. This is succeeded by aryl migration, leading to the formation of intermediate IV. Subsequently, intermediate IV transitions to intermediate V, which undergoes another oxidative addition reaction with a second aryl halide molecule to form key intermediate VI. In the final step, a reductive elimination reaction occurs, yielding the desired diaryl sulfide (VII) while simultaneously regenerating the active Pd(0) catalytic species. This regeneration enables the catalyst to participate in multiple cycles, as depicted in Fig. 12.

In the early stages of the research, the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4complex was used as a catalyst for the C–O coupling reaction. Initially, in the pursuit of optimizing the reaction conditions, iodobenzene (1 mmol) was employed as a model reaction (refer to Table 3). The investigation began by exploring the impact of varying amounts of the nanocatalyst on the reaction outcome, leading to the discovery that the optimal yield was achieved when using 0.02 g of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4. Subsequently, the effects of the base, solvent, and reaction temperature were examined, and it was determined that the best C–O cross-coupling product was produced in PEG with KOH as the most effective base at 120 °C, resulting in the highest yield of the phenol product. Based on the findings, the ideal conditions for this reaction encompass the use of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 catalyst (0.02 g) and KOH (1.2 mmol) as the base in PEG at 120 °C.

After obtaining the optimized reaction conditions, we proceeded to examine the range of substrates involving phenol and aryl halides in the presence of KOH and 0.02 g of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 in PEG at 120 °C. The findings have been consolidated in Table 4. Various aryl halides, both with electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups, showed effective reactivity with phenol, resulting in excellent isolated yields and high TOF values, as noted in Table 4. The self-coupling product for 4-bromophenol for entries 7, 8, and 10 is 8, 10, and 5%, respectively.

The mechanism of the C-O coupling reaction is illustrated in Fig. 13. In this process, an aryl halide interacts with palladium (Pd) nanoparticles, leading to the cleavage of the C-X bond (where X is a halogen). This results in the attachment of both the halogen and carbon atoms to Pd, forming a Pd(II) species. This step is crucial, as it activates the aryl halide. To facilitate the bond formation with Pd, an electron is required, and this step is often enhanced by the presence of a supporting ligand, such as a nitrogen-based ligand. The Pd(II) intermediate (referred to as intermediate 1) then reacts with a nucleophile (the aryl halide itself) in the presence of a base, like KOH. During this stage, the nucleophile attacks the carbon atom bound to Pd, replacing the halogen atom. This nucleophilic attack results in the formation of a C-O bond, displacing the halogen as the leaving group. Consequently, the C-O bond is established. Lastly, intermediate 2 undergoes reductive elimination, resulting in the production of ether while regenerating the palladium nanoparticles, as demonstrated in Fig. 13.

Hot filtration test

The heterogeneous nature of the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 catalyst was confirmed using a hot filtration test. To address this, the coupling reaction of 4-chlorophenol with phenyl iodide was initiated using the aforementioned catalyst, and the process was halted after 30 min, resulting in a 54% yield of biphenyl ether. Subsequently, this reaction was repeated, but after 30 min, the nanocatalyst was removed, and the reaction mixture was allowed to proceed for an additional 30 min in the absence of the catalyst. This resulted in a 55% yield of biphenyl ether. These findings indicate that the Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 catalyst operates under heterogeneous conditions, facilitating C–O coupling reactions accordingly.

Recyclability of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4

The study assessed the reusability and recyclability of the catalyst by conducting a model reaction involving the reaction of S8 with iodobenzene (refer to Fig. 14). Once the reaction concluded, the nanocatalyst was easily isolated from the reaction mixture using a magnet and then rinsed with acetone to eliminate any remaining product. Following drying, the recycled catalyst was employed in the subsequent reaction. Remarkably, the catalyst demonstrated consistent activity for up to 4 cycles (see Fig. 14).

The performance of Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 as a nanocatalyst was assessed by comparing it with previously reported nanocatalysts in the literature, as detailed in Table 5. This table highlights its results for C-S and C-O coupling reactions alongside those of other documented catalysts. Notably, nano-Pd-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 offers distinct advantages, including shorter reaction times, high product yields, and the use of eco-friendly solvents. These findings demonstrate that Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 serves as a highly efficient and valuable nanocatalyst for the synthesis of organic compounds.

Conclusion

In this study, we detail the preparation of palladium complexes anchored on the surface of NiFe2O4, presenting a novel, environmentally friendly, and highly reusable catalyst synthesized through a straightforward and cost-effective method. The catalyst was characterized using an array of analytical techniques, including VSM, FT-IR, TGA, XRD, ICP, EDX, TEM, and FE-SEM. Its catalytic efficiency was evaluated in C-S and C-O coupling reactions, yielding excellent conversion rates. Remarkably, the catalyst demonstrated substantial reusability, facilitated by magnetic separation, with only a marginal decrease in yield from 98 to 95% across successive reactions. Analysis via ICP confirmed negligible loss of palladium after four cycles. The catalyst’s ease of recovery, and sustained activity over multiple uses underscore its practicality. Furthermore, it is noteworthy for its utilization of commercially accessible, environmentally benign reagents, simple operational procedures, easy filtration for separation, cost-effectiveness, and chemical stability. These attributes make this catalyst an attractive and economically viable option for potential application in various organic synthesis processes. The magnetic catalyst Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 has great potential in the future. Future research should focus on greener synthesis and a deeper understanding of its mechanism of action. This catalyst is expected to have wide applications in various industries, including the production of valuable chemicals and the removal of pollutants, and contribute to sustainable development. The development of similar catalysts with multiple functions also shows a bright prospect.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study can be found within this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Peiman, S., Maleki, B. & Ghani, M. Fe 3 O 4 @ SiO 2 @ Mel-Rh-Cu : A High-Performance , Green Catalyst for Efficient Xanthene Synthesis and Its Application for Magnetic Solid Phase Extraction of Diazinon Followed by Its Determination through HPLC-UV. 8, 257–279 (2024).

Qi, L. et al. Facile synthesis of 5-aminoisophthalic acid functionalized magnetic nanoparticle for the removal of methylene blue. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 31, 457–468 (2020).

Hegde, S. & Nizam, A. Magnetically retractable tea extract stabilized palladium nanoparticles for denitrogenative cross-coupling of aryl bromides with arylhydrazines under green conditions: An alternate route for the biaryls synthesis. Catal. Commun. 187, 106862 (2024).

Ghani, M., Maleki, B., Jafari, Z. & Veisi, H. Polymethyldopamin@Fe3O4 for Magnetic Solid Phase Extraction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Combined with DES as Desorption Solvent and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Ultraviolet Detection. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 44, 2381–2393 (2024).

Nasseri, F., Nasseri, M. A., Kassaee, M. Z. & Yavari, I. Synergistic performance of a new bimetallic complex supported on magnetic nanoparticles for Sonogashira and C-N coupling reactions. Sci. Rep. 13, 18153 (2023).

Rezaei, F., Alinezhad, H. & Maleki, B. Captopril supported on magnetic graphene nitride, a sustainable and green catalyst for one-pot multicomponent synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromene and 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidine. Sci. Rep. 13, 20562 (2023).

Pormazar, S. M. & Dalvand, A. Adsorption of Reactive Black 5 azo dye from aqueous solution by using amine-functioned Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticles with L-arginine : Process optimisation using RSM. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 00, 1–20 (2020).

Hegde, S., Surendran, S., Vijayan, A. & Nizam, A. Nano-architectured polypyrrole based magnetic nanocatalyst for the N- arylation of imidazoles and fused imidazoles. Catal. Today 449, 115180 (2025).

Peiman, S. & Maleki, B. Fe3O4@SiO2@NTMPThio-Cu: A sustainable and eco-friendly approach for the synthesis of heterocycle derivatives using a novel dendrimer template nanocatalyst. Sci. Rep. 14, 17401 (2024).

Peiman, S., Maleki, B. & Ghani, M. Fe3O4@gC3N4@Thiamine: A novel heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds and microextraction of tebuconazole in food samples. Sci. Rep. 14, 21488 (2024).

Hadrup, N. et al. Pulmonary toxicity of Fe2O3, ZnFe2O4, NiFe2O4 and NiZnFe4O8 nanomaterials: Inflammation and DNA strand breaks. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 74, 103303 (2020).

Sun, F., Zeng, Q., Tian, W., Zhu, Y. & Jiang, W. Magnetic MFe2O4-Ag2O (M = Zn Co, & Ni) composite photocatalysts and their application for dye wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 103011 (2019).

Naderi, S., Sandaroos, R., Peiman, S. & Maleki, B. Novel crowned cobalt (II) complex containing an ionic liquid: A green and efficient catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of chromene and xanthene derivatives starting from benzylic alcohols. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 180, 111459 (2023).

Rayati, S., Moradi, D. & Nejabat, F. Magnetically recoverable porphyrin-based nanocatalysts for the effective oxidation of olefins with hydrogen peroxide: A comparative study. New J. Chem. 44, 19385–19392 (2020).

Yao, H., Wang, Y. & Razi, M. K. An asymmetric Salamo-based Zn complex supported on Fe3O4MNPs: A novel heterogeneous nanocatalyst for the silyl protection and deprotection of alcohols under mild conditions. RSC Adv. 11, 12614–12625 (2021).

Dippong, T. & Levei, E. A. Chapter III Synthesis and characterization of MFe2O4 (M: Zn, Ca, Mg) photocatalysts. Solid State Commun. 4, 1–12 (2021).

Hou, X. et al. Experimental Insight into the Catalytic Mechanism of MFe2O4(M = Ni, Zn and Co) on the Thermal Decomposition of TKX-50. Cent. Eur. J. Energ. Mater. 18, 223–244 (2021).

Rafiq, M., Javed, A., Nasir, M., Khan, M. & Hussain, D. A. Understanding the structural, electronic, magnetic and optical properties of spinel MFe2O4 (M = Mn Co, Ni) ferrites. Ceram. Int. 46, 4976–4983 (2019).

Ashraf, M. A., Liu, Z., Zhang, D. & Alimoradi, A. L-lysine-Pd Complex Supported on Fe 3 O 4 MNPs: A novel recoverable magnetic nanocatalyst for Suzuki C-C Cross-Coupling reaction. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5668 (2020).

Gupta, P. et al. Basic ionic liquid grafted on magnetic nanoparticles: An efficient and highly active recyclable catalyst for the synthesis of β-nitroalcohols and 4H-benzo[b]pyrans. J. Mol. Struct. 1274, 134351 (2023).

Zhang, H.-Y. et al. A magnetic metal–organic framework as a highly active heterogeneous catalyst for one-pot synthesis of 2-substituted alkyl and aryl(indolyl)kojic acid derivatives. New J. Chem. 41, 7108–7115 (2017).

Sundararajan, M. et al. A comparative study on NiFe2O4 and ZnFe2O4 spinel nanoparticles: Structural, surface chemistry, optical, morphology and magnetic studies. Phys. B Condens. Matter 644, 414232 (2022).

Fatimah, I. et al. One-pot synthesis of Fe3O4/NiFe2O4 nanocomposite from iron rust waste as reusable catalyst for methyl violet oxidation. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 8, 100369 (2023).

Hadrup, N. et al. Pulmonary toxicity of Fe2O3, ZnFe2O4, NiFe2O4 and NiZnFe4O8 nanomaterials: Inflammation and DNA strand breaks. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 74, 103303 (2019).

Kandathil, V. et al. NHC-Pd complex heterogenized on graphene oxide for cross-coupling reactions and supercapacitor applications. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5924 (2020).

Kanchana, U. S., Diana, E. J., Mathew, T. V. & Anilkumar, G. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of coumarin derivatives: An overview. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5983 (2020).

Lakshmidevi, J., Naidu, B. R. & Venkateswarlu, K. CuI in biorenewable basic medium: Three novel and low E-factor Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions. Mol. Catal. 522, 112237 (2022).

Sardarian, A. R., DindarlooInaloo, I. & Zangiabadi, M. Selective Synthesis of Secondary Arylcarbamates via Efficient and Cost Effective Copper-Catalyzed Mono Arylation of Primary Carbamates with Aryl Halides and Arylboronic Acids. Catal. Letters 148, 642–652 (2018).

Kilic, A. et al. The orthopalladation dinuclear [Pd(L1)(μ-OAc)]2, [Pd(L2)(μ-OAc)]2 and mononuclear [Pd(L3)2] complexes with [N, C, O] or [N, O] containing ligands: Synthesis, spectral characterization, electrochemistry and catalytic properties. J. Organomet. Chem. 695, 697–706 (2010).

Faria, V. W. et al. Palladium nanoparticles supported in a polymeric membrane: an efficient phosphine-free “green” catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura reactions in water. RSC Adv. 4, 13446–13452 (2014).

Mousavi-Mashhadi, S. A. & Shiri, A. On-Water and Efficient Ullmann-Type O-Arylation Cross Coupling Reaction of Phenols and Aryl Tosylates in the Presence of Fe3O4@Starch-Au as Nanocatalyst. ChemistrySelect 6, 3941–3951 (2021).

Akkoç, M., Buğday, N., Altın, S., Özdemir, İ & Yaşar, S. Highly Active Fe3O4@SBA-15@NHC-Pd Catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction. Catal. Letters https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-021-03755-w (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Photothermal synergistic catalytic oxidation of ethyl acetate over MOFs-derived mesoporous N-TiO2 supported Pd catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 322, 122075 (2023).

Rangraz, Y., Nemati, F. & Elhampour, A. A novel magnetically recoverable palladium nanocatalyst containing organoselenium ligand for the synthesis of biaryls via Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 138, 109251 (2020).

Vibhute, S. P., Mhaldar, P. M., Shejwal, R. V. & Pore, D. M. Magnetic nanoparticles-supported palladium catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling. Tetrahedron Lett. 61, 151594 (2020).

Ashraf, M. A., Liu, Z., Li, C. & Zhang, D. Fe3O4@HcdMeen-Pd(0) Organic-Inorganic Hybrid: As a Novel Heterogeneous Nanocatalyst for Chemo and Homoselective Heck C-C Cross-Coupling Synthesis of Butyl Cinnamates. Catal. Letters https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-020-03509-0 (2021).

Zong, Y. et al. Activation of peroxymonosulfate by a magnetic Co doped NiFe2O4 catalyst for efficient Bisphenol A degradation in water. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 147, 104930 (2023).

Bandgar, S. B., Vadiyar, M. M., Jambhale, C. L., Kim, J.-H. & Kolekar, S. S. Superfast ice crystal-assisted synthesis of NiFe2O4 and ZnFe2O4 nanostructures for flexible high-energy density asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 853, 157129 (2021).

Zhang, X., Bai, F., Li, M., Ru, H. & Wang, L. NiFe2O4@SiO2@PrNH2–DPA–CeCl3: A cerium-based magnetic nano dual-acid catalyst with high efficacy and recyclability for domino sequential synthesis of lactam ring-fused 1,5-benzodiazepines. Catal. Sci. Technol. 13, 3987–3999 (2023).

Basu, S., Chatterjee, S., Bhaumik, A. & Mukhopadhyay, C. Ultrasound-promoted novel route to triazabenzo[b]cyclopenta[lm]fluorenes: An efficient NiFe2O4@SiO2–SO3H nanocatalyst-assisted green synthesis. Appl. Organomet. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.6426 (2021).

Dumbre, D. K., Selvakannan, P. R., Patil, S. K., Choudhary, V. R. & Bhargava, S. K. Mesoporous, ligand free Cu-Fe solid catalyst mediated CS cross coupling of thiols with aryl halides. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 476, 54–60 (2014).

Amiri, K., Rostami, A., Samadi, S. & Rostami, A. Cu-ZSM5 as reusable catalyst for the one-pot, odorless and ligand-free C-S bond formation. Catal. Commun. 86, 108–112 (2016).

Amiri, K., Rostami, A. & Rostami, A. CuFe2O4 magnetic nanoparticle catalyzed odorless synthesis of sulfides using phenylboronic acid and aryl halides in the presence of S8. New J. Chem. 40, 7522–7528 (2016).

Mohammadinezhad, A. & Akhlaghinia, B. CoII Immobilized on Aminated Magnetic-Based Metal-Organic Framework: An Efficient Heterogeneous Nanostructured Catalyst for the C-O Cross-Coupling Reaction in Solvent-Free Conditions. Catal. Letters 150, 332–352 (2020).

Avudoddi, V., Palle, V. K. G. & Pallapothula, V. R. Recyclable and reusable nano-CuFe2O4 catalyzed C-O cross-coupling. Eur. J. Chem. 3, 298–304 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the Ongoing Research Funding program - Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-0111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anjan Kumar. Ahmed M. Naglah. Chou-Yi Hsu. Jayanti Makasana. Suhas Ballal. Munther Kadheem. Abhayveer Singh. T. KRITHIGA. Swati Mishra. and Pushpa Negi Bhakuni. Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, A., Naglah, A.M., Hsu, CY. et al. Pd(0)-Sb@A@SiO2@NiFe2O4 yolk-shell nanostructures as an effective and reusable nanocatalyst for the synthesis of symmetrical sulfides and unsymmetrical ethers. Sci Rep 15, 26454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10878-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10878-2