Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) is among the cancers with the highest incidence rates. Although multiple therapies are available, there is an unmet need for prediction of prognoses and treatment responses. Increasing evidence has shown that lipid metabolism is important for the development of BC. The tumor-promoting role of lipid metabolism in BC has inspired us to build a model to predict prognosis and stratify patients using lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) that may reflect the underlying biological mechanisms of BC. We identified a list of genes involved in lipid metabolism that were associated with the overall survival of BC. The above genes were selected by the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method to avoid overfitting, and the stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression model was applied. The BC cohort of the Cancer Genome Atlas was divided into a training cohort and a test cohort at a ratio of 1:1. A six-gene signature, comprising APOC3, CEL, CPT1A, JAK2, NFKBIA, and PLA2G1B, was developed using the training cohort. There was a clear distinction in overall survival between low- and high-risk patients in the training cohort, the test cohort, various validation cohorts, and different clinical subgroups. Then, immune cell infiltration analysis, GO and KEGG analyses were performed. Enrichment analyses were applied to explore the possible underlying mechanisms. We also analyzed the susceptibility of patients to predefined drugs in different risk groups in an attempt to identify potential therapeutic drugs. Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A (CPT1A), one of the signature genes, is a key enzyme in lipid metabolism that has been related to cancer progression. Therefore, we analyzed the prognostic values of CPT1A in public cohorts and our independent BC cohort by performing immunohistochemistry. CPT1A was significantly related to overall survival in patients with BC in the cohorts. In general, the LMRG signature can predict overall survival and potential immunotherapy response in patients with BC, including triple-negative BC. The findings have highlighted the role of lipid metabolism and CPT1A in BC, showing the implications for further research, and the signature is a potential tool for prognosis prediction and may help clinicians with clinical decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer cells are well-known for their altered metabolism preferences that can meet their phenotypic demands1. The preferences of them continuously change in response to cellular states and environmental conditions, are regulated by endogenous signals from cancer cells and signals from the tumor microenvironment, and are associated with tumor progression1. In cancer progression, aberrant lipid metabolism is one of the most prominent metabolic changes and is recognized as a critical hallmark of cancer2,3. Cancers are dependent on reprogrammed lipid metabolism to meet their increased demand for lipids and cholesterol. Abnormal lipid metabolism not only provides energy to fuel cancer cells and raw materials to build cell membranes, but also acts as the source for key signaling molecules that affect the proliferation, invasion, metastasis, drug resistance and immune escape of cancer cells3. Therefore, dysregulated lipid metabolism, including lipid synthesis and fatty acid oxidation (FAO), is closely interrelated with the sensitivity of cancer cells to ferroptosis, metastasis, reduced drug sensitivity, chronic inflammation4,5,6. The extensive correlation between lipid metabolism and cancer makes it a promising, multifaceted target for the treatment of cancer.

Breast cancer (BC) is among the cancers with the highest incidence rates in the world and is a common cause of cancer-related death in the female population, with its mortality rate constituting about 15% of the total diagnosed cases7. In the past few decades, the concept of classification-based treatment of BC has been promoted and popularized. BC can be divided into estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative types according to its molecular and metabolic characteristics. ER-positive breast cancer is further divided into the luminal A subtype and luminal B subtype, while ER-negative BC is further divided into the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-enriched subtype and basal-like subtype (triple-negative breast cancer, TNBC)7. At present, surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are the mainstay therapeutic regimens for BC7. These therapies have led to remarkable progress in the treatment of BC. However, BC is a highly complex disease with a wide variety of clinical features; the need for prediction of therapeutic responses and survival outcomes has largely been unmet, especially for TNBC, a BC subtype known for its high aggressiveness and poor prognosis8. Therefore, finding new tools for such prediction is considered a promising strategy to address the current issue.

BC arises from mammary tissues with abundant adipocyte populations, which makes it natural that lipid metabolism is important for the development of BC3,9. In previous research, deficiency in tumor glycolysis activates a metabolic switch from glycolysis to fatty acid β-oxidation to fuel TNBC growth10. In a recent study, endocrine therapy activates the FAO and Src signaling pathways that contribute to the therapeutic resistance of estrogen receptor alpha–positive breast cancer, inhibition of CPT1 could inhibit the growth of treatment-resistant cells in vitro and in vivo6. In ErbB2 + breast cancer models, long-chain fatty acid oxidation inhibition increased glucose dependency that enables survival and eventual tumor progression, and delayed tumor onset, growth, and metastasis4. The tumor-promoting role of lipid metabolism in breast cancer has inspired us to build a model to predict prognosis and stratify patients using lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) that may reflect the underlying biological mechanisms of breast cancer. In this research, we used The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database to obtain RNA sequencing data to systematically explore the expression and prognostic value of LMRGs. Subsequently, we identified a gene signature involved in lipid metabolism for prognostic purposes. This gene signature was then verified in TCGA Breast Cancer Cohort (TCGA-BRCA) and two breast cancer cohorts from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets. In addition, we tested the prognostic effect of CPT1A at the protein level with our clinical cohort. Moreover, the potential mechanisms underlying the predictive value of this gene signature were explored. This model showed prognostic significance in diverse cohorts and TCGA subgroups, and we expect it to assist prognostic management in patients with BC.

Materials and methods

Clinical datasets

Our study involved three publicly available datasets, including one TCGA dataset and two GEO datasets. Transcriptomic data with matched clinical information in TCGA are available from the Cancer Genomics Browser of The University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) (https://genomecancer.ucsc.edu). The patients in TCGA-BRCA were then randomly divided into a training group and a test group at a ratio of 1:1. Microarray data of mRNA and clinical data of two GEO datasets (GSE159956 and GSE20685) were downloaded from the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

Establishment and validation of a gene signature

The LMRGs that are closely interrelated with overall survival (OS) in BC were identified by univariate Cox analyses. The OS-related genes were further selected and the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method was applied to avoid overfitting using the “glmnet” package, as was applied in previous research11. A stepwise multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression method was utilized to optimize the model and determine the coefficients, while one standard error above the minimum criteria was selected. The risk score was calculated by a formula that consists of the product of the expression of each signature gene and its coefficient: risk score = (Gene1 expression * Gene1 coefficient) + (Gene2 expression * Gene2 coefficient) + (Gene3 expression * Gene3 coefficient) + (Gene4 expression * Gene4 coefficient). Patients were classified into a high-risk group or a low-risk group according to the risk score, and Kaplan‒Meier survival curves and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the performance of the model. Similarly, the model was evaluated in the GEO dataset (GSE159956 and GSE20685).

Analysis of immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment

Patients from TCGA-BRCA were divided into a low-risk group or a high-risk group according to the above criteria. CIBERSORT12, which incorporates the LM22 algorithm, was applied to estimate the percentages of infiltrated immune cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) of each patient.

Functional enrichment and pathway analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed using the clusterProfiler R package. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and gene set variation analysis (GSVA) were performed using the org.Hs.eg.db, clusterProfiler, enrichplot and limma R packages. c5.go.v7.4.symbols.gmt and c2.cp.kegg.v7.4.symbols were used as the annotated gene sets.

Tumor microenvironment analysis

The “maftools” R package13 was utilized to evaluate the mutational burden of the tumor, and the “ESTIMATE” R package14 was used to analyze the tumor stromal cells and immune cells in BC, which could predict the sensitivity of the different groups to immunotherapy according to the gene signature.

Drug screening

We screened potential effective drugs using the pRRophetic package15 and oncoPredict package16. Comparison of the IC50 values between low-risk and high-risk groups was conducted using the same packages. The information for chemical structure and clinical studies of the drugs was obtained from the canSAR Black database (https://cansarblack.icr.ac.uk/).

Specimens and immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were obtained from the Second Xiangya Hospital. Tissues from patients with breast cancer were made into a tissue microarray (TMA). A waiver of informed consent was acquired from the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital, in consideration of the retrospective nature of the study. The clinicopathological data of the enrolled patients in this cohort are shown in Table S1. The TMA underwent immunohistochemistry (IHC) with an antibody against CPT1A (Proteintech, 15184-1-AP; dilution 1:100), with reference to previous research17. TMA sections were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated through a graded ethanol series; antigen retrieval was achieved using citrate buffer; non-specific sites were blocked with a protein-free blocking buffer for 30 min. Primary antibody incubation against CPT1A was performed, followed by application of a secondary antibody (SeraCare, Cat# 5220-0336, MA, USA). Detection utilized DAB substrate (Servicebio, Cat# G1212, Wuhan, China). Digital images were acquired with an Olympus BH-2 microscope. Quantification of DAB staining intensity was performed using ImageJ (v1.51). The results of IHC were evaluated using an H-score, the multiplication of the percentage of positive tumor cells (0 = 1–10%, 1 = 11–40%, 2 = 41–70%, 3 = 71–100%) and the staining intensity (0 = very weak, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, 3 = strong). The H-score referred to previous research, with modifications of methods17.

Statistical analysis

R v4.0.5 and GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA, USA) were used for statistical analyses. The Wilcoxon test and Kruskal–Wallis test were applied for comparisons of two and multiple groups, respectively. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan‒Meier method. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

LMRGs are associated with prognosis in breast cancer

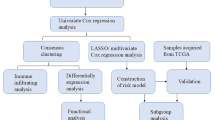

The flow diagram of this study is shown in Fig. 1. We found that there were 457 lipid metabolism-related genes that were differentially expressed between normal and tumor tissues in TCGA-BRCA (Fig S1A–D), and most of these genes were associated with each other (Fig S1E). It is likely that these genes are closely related to each other and exert a synergistic impact on the prognosis of BC patients. Therefore, we matched survival data of the TCGA-BRCA dataset with lipid metabolism gene expression data of patients to evaluate their prognostic effects. Univariate Cox analyses were used, and 10 genes with significant influence (P < 0.01) were identified (Table S2).

The LMRG signature was constructed based on TCGA-BRCA

To avoid overfitting, LASSO regression analysis was used (Fig. S2A,B), followed by multivariate Cox analysis. Then, a stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression model containing 6 LMRGs was constructed. The risk score formula is as follows: risk score = 1.0141297763517*APOC3 + 0.278113339489709*CEL + 0.229502653231649*CPT1A + (− 0.329976902852339*JAK2) + (− 0.40314453708825*NFKBIA) + (− 1.50399099571667*PLA2G1B). Among them, APOC3, CEL and CPT1A were negatively correlated with the prognosis of BC, while JAK2, NFKBIA and PLA2G1B were positively correlated with it (Fig. S2C,D).

The LMRG signature predicted prognoses effectively in TCGA cohorts

Patients from TCGA-BRCA were assigned to a training cohort and a test cohort at a ratio of 1:1 randomly. Patients in the training cohort were scored using the above formula and assigned to a high-risk group or a low-risk group on the grounds of the median risk score. Kaplan‒Meier analysis showed that compared with the low-risk group, the high-risk group had worse OS (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). To evaluate the reliability of the gene signature, an ROC curve was plotted. The area under the curve (AUC) of this gene signature in the training cohort at 1, 3 and 5 years was 0.773, 0.731 and 0.680, respectively (Fig. 2G). The distribution of risk scores is shown in Fig. 2D. Next, the test cohort was used to validate the efficiency of the gene signature. Consistent with the training cohort, the low-risk group had better OS (Fig. 2B,E). The AUCs at 1, 3 and 5 years were 0.646, 0.622 and 0.650, respectively (Fig. 2H). When this gene signature was applied to the whole TCGA-BRCA cohort, the AUCs were 0.685, 0.671 and 0.665 at 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively (Fig. 2I), and the patients from the high-risk group had a worse prognosis (Fig. 2C,F).

Construction of the LMRG signature for predicting overall survival in the training set and validation of it in the test set and the whole set. The Kaplan‒Meier curves estimate overall survival for the low- and high-risk groups based on the risk score in the training set (A), test set (B), and TCGA-BRCA (C); The distribution of risk score, survival status, and the two-gene expression panel in the training set (D), test set (E), and TCGA-BRCA (F); ROCs of LMRGs signature for prediction of overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years in the train set (G), the test set (H), and the TCGA-BRCA (I). LMRGs, lipid metabolism-related gene signature; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TCGA-BRCA, TCGA breast cancer cohort; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; AUC, area under the curve.

The LMRG signature showed good prognostic performance in different clinical subgroups of TCGA-BRCA cohorts

To further test the performance of the signature, TCGA-BRCA patients were divided into different subgroups according to tumor stage, age ( > = 65 or < 65), sex (male or female), and hormone receptor status (TNBC or non-TNBC). The heatmap revealed the relationship between risk, different clinical features and 6 LMRGs in Fig. 3A. Kaplan‒Meier curves estimated OS for the low-risk and high-risk groups on the grounds of the risk score in patients from diverse subgroups (Fig. 3B,D,F,H,J,L). The OS of the low-risk group in various subgroups was higher, and the P values were less than 0.05. In both the < 65 group and the ≥ 65 group, the AUCs were greater than 0.6 (Fig. 3C,E). The AUCs of the stage I-II group at 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.788, 0.702, and 0.656, respectively (Fig. 3G), and those of the stage III-IV group were 0.577, 0.616, and 0.676, respectively (Fig. 3I). In all subgroups, except for the sex subgroup, which could not be accurately assessed due to the small number of male patients, prognoses were well predicted. It is worth mentioning that in TNBC, the AUC at 5 years was 0.675 (Fig. 3M). This indicates that our gene signature can be well applied to patients with TNBC.

Validation of the LMRG signature in different clinical subgroups of TCGA-BRCA. The relationship between risk, different clinical features, and 6 risk score-related genes (A); Kaplan‒Meier curves estimating overall survival for the low- and high-risk groups based on the risk score in patients with different ages (B,D), stages (F,H), or disease types (J,L); ROCs of the LMRG signature for the prediction of overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years in different age subgroups (C,E), stages (G,I), or disease types (K,M). LMRGs, lipid metabolism-related gene signature; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TCGA-BRCA, TCGA breast cancer cohort; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve.

The LMRG signature shows good performance in different validation cohorts

To further validate the performance of this gene signature, two breast cancer datasets, GSE159956 and GSE20685, were used for evaluation. First, the gene signature formula was utilized to score each patient from the two datasets. Then, the high- and low-risk groups were determined on the grounds of their optimal cutoff values (0.3327518 for GSE20685, 0.09740455 for GSE159956). The results showed that the efficiency of the model in predicting prognosis in the two datasets was acceptable (Fig. 4A–F). In both cohorts, the high-risk patients were characterized by worse prognoses (Fig. 4A,B).

Validation of the lipid metabolism-related gene signature for predicting overall survival in GSE159956 and GSE20685. Survival curve (A), risk score distribution, survival status (C), and ROC (E) in GSE159956. Survival curve (B), risk score distribution, survival status (D), and ROC (F) in GSE20685. ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; AUC, area under the curve.

Analysis of the tumor microenvironment in the High-risk and Low-risk groups

To preliminarily understand the mechanism of this gene signature, immune infiltration analyses were performed. The patients in the high-risk and low-risk groups of the TCGA-BRCA cohort were analyzed and compared. The immune cell infiltration in each patient is shown in Fig. 5A, and the different proportions of immune cell infiltration in the two groups are compared in Fig. 5B,C. It can be observed from the figure that the infiltration levels of naive B cells, CD8 + T cells, resting memory CD4 + T cells, T follicular helper cells, gamma delta T cells, resting NK cells, activated NK cells, monocytes and resting dendritic cells were higher in the low-risk group, while the levels of M0, M2 macrophages were lower. The stromal score and immune score were higher, the tumor purity was lower, and the ESTIMATE score was higher in the low-risk group (Fig. 5D). Additionally, immune checkpoint gene expressions (CD274, PDCD1, PDCD1LG2, TIGIT) in the low-risk group were higher than that in the high-risk group (Fig. 5E). The results may indicate the presence of an immune inflammatory microenvironment in the low-risk group, which may be related to a higher possibility of response to immunotherapy.

Immune infiltration analyses in TCGA-BRCA patients. The proportions of 22 immune cells in 1069 breast cancer patients (A) and the comparison of their infiltration in high- and low-risk groups (B); Bubble chart of 22 immune cells in TCGA-BRCA (C); Estimation of Stromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumors using Expression data (ESTIMATE) analyses of TCGA-BRCA (D); Comparison between high-risk group and low-risk group with various expression of checkpoints (E). TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TCGA-BRCA, TCGA breast cancer cohort.

Enrichment analyses of pathways revealed possible mechanisms of the signature

To reveal the potential mechanism of the LMRG signature, GO and KEGG analyses were performed between the high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. 6A–D). At the same time, we also applied GSVA and GSEA to seek the molecular mechanism of the gene signature based on LMRGs (Fig. 6E–H). The most significantly enriched GO and KEGG terms are shown in Table S3. Negative regulation of glucose import, positive regulation of Th1 immune response, etc., were enriched in the low-risk group. Notably, many adaptive immune response pathways were upregulated in the low-risk group, which may explain the better survival. Interestingly, pathways related to metabolism were enriched in the high-risk group.

Biological features and pathway analyses of the lipid metabolism-related gene signature. GO (A–C) and KEGG analyses (D) of genes in the high- and low-risk groups, with annotations for each ID shown in Table S3. Heatmap showing the GO (E) and KEGG (F) analyses of the LMRGs in the 2 risk groups. GSEA of GO terms (G,H) correlated with the risk score. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TCGA-BRCA, TCGA breast cancer cohort; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis.

Potential drugs targeting lipid metabolism in patients with TNBC

Drugs with significant different IC50 values between different risk groups were screened out in clinical subgroups of TNBC using the pRRophetic package (Fig S3A, Table S4). Among them, BMS-754807 (Fig. 7D) and OSI.906 (linsitinib, Fig. 7E) are inhibitors of type I insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-1R)18, while VX.680 (Fig. 7F) is a pan inhibitor of the Aurora kinases, key regulators of mitotic progression and are commonly upregulated in human cancers19. IGF-1R has important effects on glucose and lipid metabolism20. When PKM2 is inhibited, TNBC could be driven by metabolic switch from a metabolically heterogeneous-lineage plastic cell state to an FAO-dependent-lineage committed cell state10. Specifically, IGF-1 had a significant increase in FAO21. In our analyses, low-risk group patients were more sensitive to BMS-754807, OSI.906, and VX.680 (Fig S3A, Table S4). Moreover, in our results, TNBC patients in the low-risk group of the LMRG gene signature were more sensitive to BMS-754807, OSI.906, and VX.680 (Fig. 7A–F). We also analyzed drug sensitivity using the oncoPredict package (Fig. S4). The adjusted P value threshold was set at P < 0.01, and the IC50 value changes between groups were set at changes > 10. Finally, 39 drugs were selected for display. The IC50 values of the drugs were higher in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group in TCGA-BRCA and the other two subgroups (Fig. S4).

Validation of CPT1A in an independent cohort

FAO is correlated with the spread, migration and invasion of breast cancer6,22. Fatty acid-activating enzymes are located in the cytoplasm, while the enzymes required for fatty acid β-oxidation are mainly located in the matrix of mitochondria. Long-chain fatty acids need the help of carnitine acyltransferase I to enter the mitochondrial matrix23. Carnitine acyltransferase is a major rate-limiting enzyme in FAO. A key molecule of this system is CPT1A, which is mainly located on the outer membrane of mitochondria and promotes the formation of the carnitine lipid acyl complex, and facilitates β-oxidation23.

CPT1A is a key enzyme in long-chain fatty acid oxidation and has been reported to be indispensable in tumor onset, growth, metastasis in HER2 + breast cancer4. CPT1A can act with L-carnitine to drive ferroptosis-resistance and CD8 + T cells inactivation in cancer24. CPT1A augments NK cells’ metabolic resilience and switches it to fatty acid metabolism to facilitate NK’s anti-tumor response during cyclic fasting25. Therefore, we analyzed the prognostic values of CPT1A. Low expression of CPT1A was related to better OS in breast cancer patients across the above three public cohorts (Fig. 8A–C). We have also performed subgroup analyses. The results showed that in non-TNBC patients in TCGA-BRCA, GSE20685, and ER positive patients in GSE159566, a low expression of CPT1A was related to better survival (Fig S5). For further validation, we performed IHC assays in our independent breast cancer cohort. The results of IHC were consistent with those at the transcriptional level. Patients with a low CPT1A expression had significantly better OS than those with a high CPT1A expression (Fig. 8D). The AUCs of the independent cohort at 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.823, 0.834, and 0.862, respectively (Fig. 8E). Representative IHC images are displayed in Fig. 8G,H. Compared with early breast cancer patients, advanced breast cancer patients were characterized by a higher CPT1A expression (Fig. 8F) (p = 0.0049).

Validation of CPT1A in the cohorts. Kaplan‒Meier curves estimating overall survival for low and high expressions of CPT1A based on the risk score in TCGA-BRCA, GSE159956, and GSE20685 cohorts (A–C). Kaplan‒Meier curves estimating overall survival for low and high CPT1A expressions based on the H-score from our cohort (D); ROCs of CPT1A protein for prediction of overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years in our cohort (E); Representative immunohistochemical images (G,H); H-scores for different clinical stages (F); TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TCGA-BRCA, TCGA breast cancer cohort; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; **p < 0.01.

Discussion

BC is a complex disease with broad clinical characteristics, and is characterized by a heterogeneous response to clinical drugs and a difficult-to-predict prognosis. Surgery, endocrine therapy, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are the mainstays for the treatment of breast cancer7.

Lipid metabolism is one of the most prominently changed metabolic pathways in cancer. The pentose phosphate pathway has long been the focus of cancer therapy due to the Warburg effect. However, it is impossible to ignore that most cancers require altered lipid metabolism to meet their unlimited energy requirements26. In fact, harsh conditions, such as hypoxia and acidic environments, are common in cancer and trigger lipid metabolism reprogramming27. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer mainly includes de novo lipid synthesis and fatty acid β-oxidation. Key lipogenic enzymes, including fatty acid synthase (FASN), ATP citrate lyase, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase, are present in most cancer cells26,27. It should be noted that a high level of FASN is inversely related to cancer prognosis28,29,30. Citrate produced by a variety of metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, is frequently used in lipid synthesis31,32. Excess energy is also stored by cancer cells as lipid droplets, which can be further lipolyzed into free fatty acids (FFAs)33. Interestingly, as cancer progresses, cancer cells are more prone to express CD36, a cell-surface fatty acid transferase. Cancer cells can obtain fatty acids for lipid catabolism through CD3634. Dysregulated lipid metabolism (including lipid synthesis and FAO) is correlated with the sensitivity of cancer cells to ferroptosis, metastasis, and reduced drug sensitivity34. There is a mass of evidence that lipid metabolism is important for the development of BC2,3. Therefore, we constructed a gene signature related to lipid metabolism based on the TCGA-BRCA dataset to assess the risk of breast cancer patients, aiming to guide the prognostic management and immunotherapy response prediction of these patients and explore the related mechanisms.

To reveal the prognostic impact of the lipid metabolism-related genes, univariate Cox analyses were performed, and 10 genes with significant prognostic impact (P < 0.01) were identified. Then, LASSO regression analysis was applied to avoid model overfitting, yielding six optimal genes: APOC3, CEL, CPT1A, JAK2, NFKBIA, and PLA2G1B. APOC3 gene encodes apolipoprotein C3, which is mainly synthesized in the liver and is a key regulator of triglyceriderich lipoprotein metabolism35. Loss-of-function in APOC3 were associated with reductions in triglyceride and remnant cholesterol levels and could reduce the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease35. CEL is the gene encoding carboxyl ester lipase, a protein secreted mainly from pancreatic acinar cells and activated by bile salts in the duodenum; it hydrolyses a wide variety of dietary lipids, cholesteryl esters, cholesterol, ceramides, triacylglycerides, phospholipids, lipid-soluble vitamins and can regulate atherosclerosis progression36. It has been reported that a high expression of carboxyl ester lipase is closely related to a low survival rate in breast cancer patients37. PLA2G1B encodes phospholipase A2, a calcium-dependent enzyme produced by the acinar cells of the pancreas that promotes the hydrolysis of the SN-2 position of membranous glycerophospholipids and the release of arachidonic acid and hemolytic phospholipids. PLA2G1B participated in a variety of biological processes, and was associated with tumor initiation, progression and metastasis38. The gene signatures can be used to evaluate the prognosis effectively in TCGA-BRCA, GSE159956 and GSE20685. Previously, Wang et al. established a pyrimidine metabolism-related gene signature for prognosis prediction and immune microenvironment description of BC39. In their model, the AUCs at 1, 3, 5 years were 0.573, 0.648, and 0.633, compared to that of 0.685, 0.671, and 0.665 in TCGA-BRCA in our signature. In another study, Jin et al. identified an absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion genes-related risk scoring model for BC40. The AUC was not shown, but we observed a cross-over between high and low risk groups in the survival curve, which reduced the model’s stability to some extent. The comparisons have highlighted the robustness of our signature and inspired us to explore the underlying mechanisms.

To explore the potential mechanism, we compared the infiltration of immune cells between different risk groups. Compared to the high-risk group, the low-risk group had an increased number of inflammatory immune cells, such as CD8 + T cells, and a decreased number of M2 macrophages. Moreover, the low-risk group had a higher immune score and stromal score and a lower tumor purity score, suggesting that the low-risk group may be more susceptible to immunotherapy. In the high-risk group, most of the functional pathways were related to metabolism, whereas in the low-risk group, they were mostly immune-related. This provides some evidence to explore the interaction between lipid metabolism and immune cells in the future. According to the IC50 value, three potential sensitive drugs (BMS-754807, OSI.906, and VX.680) for TNBC patients in the low-risk group were identified. These drugs may be promising treatments or combinatorial options targeting lipid metabolism for patients with TNBC.

FAO provides massive energy for cancer cells. The activation of medium- and long-chain fatty acids into acyl-CoA requires the help of carnitine acyltransferase to enter the mitochondria for β-oxidation. Human L-carnitine acyltransferases include carnitine acetyl transferase (CRAT), carnitine octyl transferase (CROT), carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1 (CPT1) and carnitine palmitoyl transferase-2 (CPT2). CRAT is present in the mitochondrial matrix, peroxisomes, and nucleus and shows a preference for short-chain acyl-CoA esters such as acetyl-CoA. CRAT is present in the mitochondrial matrix, peroxisomes, nucleus and shows a preference for short-chain acyl-CoA esters such as acetyl-CoA41. Long-chain fatty acyl-CoA requires the help of CPT1A to form acylcarnitine acyl complexes that easily pass through the mitochondrial membrane and enter the mitochondrial matrix mediated by acylcarnitine translocase (CACT). After entering the mitochondrial matrix, it is converted back to long-chain fatty acyl-CoA under the catalysis of CPT2 and then undergoes β-oxidation42. CPT1A is mainly located on the mitochondrial outer membrane, but it may also reside in extracellular vesicles (EVs) and play a role in EV-mediated cancer biological activities23,43. CPT1A controls the rate-limiting step of FAO, whose increase is considered as a key metabolic feature of cancer4,23,24. In addition, increased β-oxidation or upregulation of CPT1A expression is a marker of poor prognosis in many cancers, including breast cancer44,45,46,47. Studies have reported that the expression of CPT1A is upregulated in ER-positive breast cancer cases, and the majority of breast cancer cell lines have elevated CPT1A protein levels48. Regulated by SLC31A1, IGF2BP1, CD24, or OVOL2 in breast cancer, CPT1A promotes breast cancer stemness, proliferation, motility, angiogenesis, or therapy resistance through several oncogenic signaling pathways, such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, and Nrf2/NQO14,44,46,49,50,51. Overall, these studies suggest that CPT1A plays an important role in breast cancer progression and is a promising target for breast cancer. Therefore, we focused on CPT1A. CPT1A was not only analyzed in different public cohorts at the mRNA level but was also validated at the protein level using our own cohort. At the mRNA level, a high expression of CPT1A was related to a worse prognosis in TCGA-BRCA, GSE159965 and GSE20685 cohorts. As observed from the IHC results of the tissue array, compared with patients with early stage breast cancer, patients with advanced breast cancer tend to express a high level of CPT1A, and a high expression of CPT1A often corresponds to a worse prognosis. This shows that our gene signature is a robust prognostic model for BRCA patients. In the immunohistochemical images, most of the positive areas were located inside the cells. Whereas, there were also a few positive areas located outside the cells, which indicated that CPT1A may be secreted through extracellular vesicles and that CPT1A may also be used as an indicator for monitoring early breast cancer.

The study has some flaws. First, this study was retrospective rather than prospective. In addition, the analysis of this gene signature for immunotherapy and drug sensitivity is indirect and needs to be verified in clinical trials. Finally, due to the limited number of drugs in the database, the sensitivity to many drugs, including anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy drugs, cannot be analyzed.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed a gene signature based on the genes involved in lipid metabolism that is a good predictor of OS and drug sensitivity. The signature was verified in three public datasets, our independent cohort, and can be used as a tool for survival and treatment response prediction. The performance of the signature has highlighted the role of lipid metabolism and CPT1A in breast cancer, showing the implications for further research on them. Future validation of the model will further improve its effectiveness.

Data availability

The names of the repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the “Science Data Bank” repository, https://www.scidb.cn/en/s/biQvMv. Other data in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Demicco, M., Liu, X., Leithner, K. & Fendt, S. Metabolic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat. Metab. 6 (1), 18–38 (2024).

Terry, A. R. & Hay, N. Emerging targets in lipid metabolism for cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 45 (6), 537–551 (2024).

Wan, M. et al. Lipid metabolic reprograming: the unsung hero in breast cancer progression and tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer. 24 (1), 61 (2025).

Nandi, I. et al. Targeting fatty acid oxidation enhances response to HER2-targeted therapy. Nat. Commun. 15 (1), 6587 (2024).

Lin, J., Lai, Y., Lu, F. & Wang, W. Targeting ACSLs to modulate ferroptosis and cancer immunity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. (2024).

Ahn, S. et al. Metabolomic rewiring promotes endocrine therapy resistance in breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 84 (2), 291–304 (2024).

Xiong, X. et al. Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 10 (1), 49 (2025).

Guo, Z. et al. Tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Biomark. Res. 12 (1), 166 (2024).

Loibl, S., Poortmans, P., Morrow, M., Denkert, C. & Curigliano, G. Breast cancer. Lancet. 397 (10286), 1750–1769 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Metabolic switch regulates lineage plasticity and induces synthetic lethality in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. Metab. 36 (1), 193–208 (2024).

Moller, P. L. et al. Predicting the presence of coronary plaques featuring high-risk characteristics using polygenic risk scores and targeted proteomics in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Genome Med. 16 (1), 40 (2024).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 12 (5), 453–457 (2015).

Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28 (11), 1747–1756 (2018).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Geeleher, P., Cox, N. & Huang, R. S. pRRophetic: an R package for prediction of clinical chemotherapeutic response from tumor gene expression levels. PLoS One. 9 (9), e107468 (2014).

Maeser, D., Gruener, R. F. & Huang, R. S. OncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief. Bioinform. 22 (6), bbab260 (2021).

Stucchi, S. et al. B7-H3 and CSPG4 co-targeting as Pan-CAR-T cell treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer. 13 (5), e011533 (2025).

Fuentes-Baile, M. et al. Differential effects of IGF-1R small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors BMS-754807 and OSI-906 on human Cancer cell lines. Cancers (Basel). 12 (12), 3717 (2020).

Du, R., Huang, C., Liu, K., Li, X. & Dong, Z. Targeting AURKA in cancer: molecular mechanisms and opportunities for cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer. 20 (1), 15 (2021).

Basu, R., Boguszewski, C. L. & Kopchick, J. J. Growth hormone action as a target in cancer: significance, mechanisms, and possible therapies. Endocr. Rev. 46 (2), 224–280 (2025).

Carboni, J. M. et al. BMS-754807, a small molecule inhibitor of insulin-like growth factor-1R/IR. Mol. Cancer Ther. 8 (12), 3341–3349 (2009).

Xiong, Z. et al. MANF facilitates breast cancer cell survival under glucose-starvation conditions via PRKN-mediated mitophagy regulation. Autophagy. 21 (1), 80–101 (2025).

Rodriguez-Rodriguez, R. et al. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. CXIX. Fundamental insights and clinical relevance regarding the carnitine palmitoyltransferase family of enzymes. Pharmacol. Rev. 77 (3), 100051 (2025).

Ma, L. et al. Targeting carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A (CPT1A) induces ferroptosis and synergizes with immunotherapy in lung cancer. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9 (1), 64 (2024).

Meng, Y. et al. Glycolytic enzyme PFKL governs lipolysis by promoting lipid droplet–mitochondria tethering to enhance β-oxidation and tumor cell proliferation. Nat. Metab. 6 (6), 1092–1107 (2024).

Martin-Perez, M., Urdiroz-Urricelqui, U., Bigas, C. & Benitah, S. A. The role of lipids in cancer progression and metastasis. Cell. Metab. 34 (11), 1675–1699 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Reprogramming of lipid metabolism mediates crosstalk, remodeling, and intervention of microenvironment components in breast Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 20 (5), 1884–1904 (2024).

Xu, L. et al. FASN-mediated fatty acid biosynthesis remodels immune environment in Clonorchis sinensis infection-related intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 81 (2), 265–277 (2024).

Jiang, T. et al. The m(6)A modification mediated-lncRNA POU6F2-AS1 reprograms fatty acid metabolism and facilitates the growth of colorectal cancer via upregulation of FASN. Mol. Cancer. 23 (1), 55 (2024).

Xiong, Q. et al. Fatty acid synthase is the key regulator of fatty acid metabolism and is related to immunotherapy in bladder cancer. Front. Immunol. 13, 836939 (2022).

Menendez, J. A. & Lupu, R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7 (10), 763–777 (2007).

Koo, J. H. & Guan, K. L. Interplay between YAP/TAZ and metabolism. Cell. Metab. 28 (2), 196–206 (2018).

Zadoorian, A., Du, X. & Yang, H. Lipid droplet biogenesis and functions in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 19 (8), 443–459 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Interplay of CD36, autophagy, and lipid metabolism: insights into cancer progression. Metabolism. 155, 155905 (2024).

Ballantyne, C. M. et al. Plozasiran, an RNA interference agent targeting APOC3, for mixed hyperlipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 391 (10), 899–912 (2024).

Gravdal, A. et al. The MODY-Causing mutation of the human carboxyl ester lipase gene (CEL) triggers chronic pancreatitis but not diabetes in mice. Gastroenterology. 161–164 (2025).

Cui, Y., Jiao, Y., Wang, K., He, M. & Yang, Z. A new prognostic factor of breast cancer: high carboxyl ester lipase expression related to poor survival. Cancer Genet. 239, 54–61 (2019).

Guan, S. et al. Identifying potential targets for preventing cancer progression through the PLA2G1B Recombinant protein using bioinformatics and machine learning methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 276, 133918 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. A pyrimidine metabolism-related gene signature for prognosis prediction and immune microenvironment description of breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 23 (1), 698 (2025).

Jin, J., Zhao, X., Deng, M. & Du, L. Role of ADME genes in breast cancer prognosis: an analysis of risk scoring models based on multi-omics data. Front. Oncol. 15, 1582862 (2025).

Schlaepfer, I. R. & Joshi, M. CPT1A-mediated fat oxidation, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Endocrinology. 161 (2), bqz046 (2020).

Cao, Y. Adipocyte and lipid metabolism in cancer drug resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 129 (8), 3006–3017 (2019).

Yin, C. et al. MSCs with upregulated lipid metabolism block hematopoietic stem cell differentiation via Exosomal CTP-1A in MDS. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 16 (1), 53 (2025).

Ma, X. et al. CPT1A/HIF-1alpha positive feedback loop induced fatty acid oxidation metabolic pathway contributes to the L-ascorbic acid-driven angiogenesis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 27 (1), 74 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. RNF5 exacerbates steatotic HCC by enhancing fatty acid oxidation via the improvement of CPT1A stability. Cancer Lett. 611, 217415 (2024).

Lu, R. et al. Loss of OVOL2 in triple-negative breast cancer promotes fatty acid oxidation fueling stemness characteristics. Adv. Sci. 11 (24), 2308945 (2024).

Jiang, N. et al. Fatty acid oxidation fuels glioblastoma radioresistance with CD47-mediated immune evasion. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 1511 (2022).

Balaban, S. et al. Adipocyte lipolysis links obesity to breast cancer growth: adipocyte-derived fatty acids drive breast cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancer Metab. 5, 1 (2017).

Shi, J. et al. Stabilization of IGF2BP1 by USP10 promotes breast cancer metastasis via CPT1A in an m6A-dependent manner. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 19 (2), 449–464 (2023).

Murthy, D. et al. CD24 negativity reprograms mitochondrial metabolism to PPARα and NF-κB-driven fatty acid β-oxidation in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 587, 216724 (2024).

Li, X. et al. SLC31A1 promotes chemoresistance through inducing CPT1A-mediated fatty acid oxidation in ER-positive breast cancer. Neoplasia. 61, 101125 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.M. designed this study and performed bioinformatic analyses. Y.J. was responsible for statistics and writing articles. T.D. was responsible for the revision of the manuscript and the supervision of the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study used publicly available human data. An exemption of ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the National Clinical Medical Research Center of The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval number: 2024 No. M03).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mai, W., Jiao, Y. & Deng, T. A lipid metabolism-related gene signature for risk stratification and prognosis prediction in patients with breast cancer. Sci Rep 15, 27281 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10879-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10879-1