Abstract

This research examines the influence of exogenous indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) on growth parameters and cadmium stress resistance in Sorghum bicolor (L. Moench). The plants were grown in pots, each filled with 4.5 kg of sand. After 21 days, root treatment with indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) was applied using five concentrations (0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 µM) under three cadmium (Cd) levels (0, 40, and 80 ppm). Applied Cadmium stress significantly reduced plant growth, with reductions in root length (12.73–15.88%), shoot length (17.60–19.25%), and plant height (10.62–14.88%). All growth parameters were improved with the application of 200 µM IAA, increasing root length (20.25–28.25%), shoot length (35.68–45.68%), and plant height (20.37%). The highest level of cadmium stress (80 ppm) was the most detrimental, while the 200 µM IAA treatment produced the most favorable results. Under cadmium stress, IAA application reduced the uptake of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions by 7.69–9.52%, 3.70–7.31%, and 6.66–7.69%, respectively, as well as Cd2+ by 2.50–5.26%. Despite these reductions, IAA application significantly enhanced antioxidant activities, including catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD). At 200 µM IAA, antioxidant enzyme activities were increased by 4.65% (SOD), 8.82% (POD), 10.06% (CAT), and 17.9% ascorbate peroxidase (APX). The treatment also boosted chlorophyll content (17.46–22.85%), while reducing oxidative stress markers such as H2O2 (29.4–40.8%) and malondialdehyde (38.9–42.1%). These findings suggest that IAA effectively mitigates cadmium-induced stress by improving growth parameters and physiological responses. Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms underlying IAA-mediated cadmium stress alleviation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the world’s fifth most widely cultivated grain crop, Sorghum bicolor (L. Moench) plays a vital role in global agriculture. Sorghum bicolor has gained considerable attention as a sustainable crop to address global food security challenges1. Belonging to the Poaceae family sorghum is well adapted to grow in a wide range of climate conditions, including arid and semi-arid regions. It is cultivated for worldwide for various uses such as food grain, starch production, animal fodder, and biofuel grain2. As an annual cereal crop, sorghum possesses a deep, fibrous root system that supports efficient water absorption and soil anchorage3. Its stem features succulent nodes and internodes, which store moisture and nutrients. A protective waxy coating on the stem surface minimizes water loss through transpirations. This structural adaptation enhances sorghum ability to withstand prolonged drought making it an ideal crop for climate resilient agriculture4. Sorghum is a nutrient dense crop rich in carbohydrates such as starch, sucrose, and cellulose. Its grains are highly valuable, containing abundant starch and protein content with approximately 70% of the protein being easily digestible and highly beneficial of digestive health5. Additionally, sorghum is a natural source of polyphenolic compounds, particularly flavonoids, which exhibits strong antioxidant properties6.

Heavy metals, particularly cadmium (Cd), are among the most harmful environmental pollutants due to their high toxicity, long term persistence in ecosystem, and tendency to bioaccumulate in living organisms7. Cd adversely affects plant growth and yield by disrupting the cell cycle, including the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and interfering with enzymatic activities and nutrient uptake mechanism8. High levels of Cd, accumulation in plants leads to reduced germination rates, increase water stress, nutrient imbalances, impaired photosynthesis, and metabolic disruptions, ultimately diminishing crop yield and quality9. Cd poisoning hampers plant growth and disrupting cellular and biochemical processes, resulting in a significant decline in morphophysiological traits10. Like other heavy metals, Cd induces in oxidative damage by triggering the excessive production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and enhancing lipid peroxidation in plants leading to cellular and membrane damage11. Cd is a highly toxic element that enhances the production of ROS, which inhibit photosynthetic activity and severely significant threaten the growth and development of sorghum12. Cd toxicity in soil depletes essential nutrients and disrupts photosynthetic activity in sorghum13. Cd stress can hinder plant growth and disrupt metabolic balances in plants14. In sorghum plants, Cd accumulation interferes with physiological processes such as photosynthesis ultimately leading to stunted growth15. Sorghum is an important grain crop valued for it use in fodder, human nutrition, and fiber production16. In recent years, plant growth regulators have gained increasing attention for their ability to mitigate the toxic effects of heavy metals in plants. These exogenous hormones act as signaling molecules that influence plant physiology and various biological processes17.

Foliar treatments with exogenous hormones have been shown to enhance stress tolerance in plants exposed to heavy metals18. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) plays a crucial role in regulating plant morpho-physiological activity. Studies have shown that various growth hormones positively influence root and shoot elongation, with IAA playing a key role in alleviating cadmium induced-stress in plants18,19. IAA is essential for maintaining plant physiological functions and promoting microbial interactions in the rhizosphere, thereby improving sorghum plant growth and development20. The production of IAA by plants can stimulate the morphological activity of beneficial rhizosphere bacteria, which in turn promotes plant development and yield. In sorghum, the application of such bacteria has been shown to enhance tryptophan metabolism, resulting in improved in shoot height and root length, and ultimately leading to increased crop productivity21. IAA stimulates the growth of beneficial bacteria in sorghum roots, which release sugars and proteins that contribute to improved sorghum nutrition and yield22. The synthesis of IAA in sorghum is directly associated with improved root growth and branching23. IAA treatment in mustard plants improved Cd absorption likely due to the stimulation of conducting tissue development (xylem and phloem), increased cell division, and thicker root structures, which together help mitigate Cd toxicity24.

This study exclusively focuses on the dual role of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in reducing Cd toxicity and enhancing the growth of Sorghum bicolor under heavy metal stress. It explores the interaction between IAA and rhizosphere bacteria, revealing an innovative aspect of plant–microbe relationships. Unlike prior research, it specifically examines IAA’s effect on cadmium uptake and plant development. The findings offer valuable insights into bio-based strategies for managing heavy metal contamination. This work supports the development of more resilient and productive crops in polluted environments.

Materials and methods

A pot experiment was conducted at the Botanical Garden, University of Agriculture Faisalabad (PARS-UAF), to assess the morphological, physiological, biochemical, and ionic responses of Sorghum bicolor (L. Moench) to Cd stress and exogenous IAA application (Fig. 1A, B). The study was conducted in completely randomized design (CRD) factorial arrangement and each treatment was replicated three times. Certified seeds of sorghum variety, Hegari, were obtained and sown in plastic pots (15 × 10 cm) filled with 4.5 kg of clean, sun-dried sand. The sand was pre- treated by sieving to remove stone and organic debris. Three seeds were planted per pot and thinned to one healthy seedling after germination. Plants were irrigated regularly using half-strength Hoagland nutrient solution until the beginning of treatments. After three weeks of germination, Cd was applied as cadmium chloride (CdCl2) at three concentrations such as (0 ppm (control), 40 ppm, and 80 ppm), and simultaneously, IAA was applied at 0 (control), 50, 100, 150, and 200 µM. Data were recorded on key morphological traits including plant height, root and shoot length, number of leaves and branches, and fresh and dry biomass. Physiological and ionic parameters measured included leaf area, leaf area index, chlorophyll pigments (a, b, total, a/b ratio), carotenoids, and concentrations of Na+, K+, and Ca2+. Antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, POD, catalase, APX), Cd2+ ion accumulation, and oxidative stress indicators (MDA, H2O2) were also evaluated.

Growth parameters

Growth parameters were recorded as described by Singh, et al.25. Two plants per replication were measured for root/shoot length, plant height, leaves, and branches. Fresh weights of roots and shoots were recorded after cleaning with distilled water. Samples were sun-dried for a day, then oven-dried at 85 °C to recorded dry weights.

Leaf area was calculated using the formula: Leaf Area = Leaf Length × Leaf Width × 0.689. Leaf area index (LAI) was determined as: LAI = Leaf Area / Land Area.

Physiological parameters

Physiological parameters were determined following the method of Arnon26.

Chlorophyll contents

Chlorophyll content was estimated by extracting 0.5 g of fresh leaf tissue in 5 mL of 80% acetone, with the extract stored overnight at 10 °C. Absorbance readings were taken at 480 nm for carotenoids, 645 nm for chlorophyll b, and 663 nm for chlorophyll a using a spectrophotometer. The concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids were calculated using standard equations. Chlorophyll a was calculated as [12.7(OD663) – 2.69(OD645)] × V / (1000 × W), while chlorophyll b was determined as [22.9(OD645) – 4.68(OD663)] × V / (1000 × W). Total chlorophyll content was calculated using the formula [20.2(OD645) – 8.02(OD663)] × V / (1000 × W), and the chlorophyll a/b ratio was obtained by dividing the value of chlorophyll a by chlorophyll b. Carotenoid content was computed as [OD480 + 0.114(OD663) – 0.638(OD645)] / 2500. In these formulas, OD represents optical density, V is the extract volume in milliliters, and W is the fresh tissue weight in gram.

Cadmium content and ionic analysis

The following nutrients attributes were calculated.

Ion Test (Na+, Ca2+ , K+)

Mineral ion concentrations in roots were determined using the digestion method of Wolf27. Dry plant roots were digested in 2.5 mL concentrated H2SO4 at room temperature. After adding 4 mL of 35% H2O2, the mixture was heated at 350 °C until crystal white, then filtered and diluted to 50 mL. Ion concentrations were analyzed using a flame photometer.

Cadmium content

The method for extracting Cd from roots followed the procedure described by Chen et al.28. Roots were soaked in 20 mM Na2-EDTA for 15 min to eliminate surface-bound Cd ions, then dried and powdered. A 0.1 g root sample was digested with 5 mL HNO3 and 1 mL HClO4 at 180 °C for 8 h. The resulting solution was filtered and diluted with deionized water. Cadmium concentrations were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

Enzymes extractions

SOD (superoxide dismutase) analysis

SOD activity was determined using a reaction mixture containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 200 mM methionine, 1.125 mM nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), 1.5 mM EDTA, 75 µM riboflavin, and the enzyme extract29. The reaction was initiated by exposing the mixture to light, and absorbance was recorded at 560 nm after 10 min to assess SOD activity.

POD (peroxidase) analysis

POD activity was assessed using a reaction mixture containing 2.5 mL of phosphate buffer, 0.2 mL of 1% guaiacol, 0.1 mL of 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, and 0.2 mL of enzyme extract. The change in absorbance was recorded at 470 nm to quantify enzyme activity.30.

Catalase (CAT) analysis

CAT activity was measured using a reaction mixture comprising 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 15 mM hydrogen peroxide, and the enzyme extract31. The decrease in absorbance at 240 nm was monitored over a period of 180 s to determine enzyme activity.

APX (ascorbate peroxidase) analysis

APX activity was measured using a mixture of root extract, potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), ascorbate, EDTA, and hydrogen peroxide32. Enzyme activity was determined spectrophotometrically by monitoring the oxidation of ascorbate at 290 nm.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

The levels of H2O2 and malondialdehyde (MDA) were determined as follows:

H2O2 content

The H2O2 content was determined by homogenizing 0.2 g of root tissue in 0.1% trichloroacetic acid33. The mixture was centrifuged, and 50 µL of the supernatant was mixed with 100 µL of 1 M KI and 50 µL of potassium phosphate buffer. Absorbance was measured at 390 nm to quantify H2O2 levels.

Measurement of lipid peroxidation

The MDA content was measured by homogenizing 100 mg of root tissue in 65 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8)34. The mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was treated with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and trichloroacetic acid (TCA), heated for 25 min, and then centrifuged again. Absorbance was measured at 532 nm to determine MDA levels.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using ANOVA, and significant differences among treatment means were determined using the least significant difference (LSD) test at a 5% significance level35. Sigma Plot and Microsoft Biorender were used for graphical representation, while R was employed for heatmaps, principal component analysis (PCA), and correlation analysis.

Results

Morphological characters

The growth of sorghum significantly declined when exposed to Cd stress (P ≤ 0.05), at both 40 ppm and 80 ppm Cd treatments. Specifically, root length (RL) decreased by 15.88–12.73% at 40 ppm, and by 13.65–10.55% at 80 ppm. Shoot length (SL) was reduced by 17.60–15.53% at 40 ppm and by 19.25–13.75% at 80 ppm. Plant height (PH) also declined by 10.62–9.85% at 40 ppm and by 14.88–12.85% at 80 ppm Cd stress compared to the control conditions (Fig. 2A–F). Similarly, the number of leaves (NOL) and branches (NOB) decreased by 3.94% and 8.96% for NOL, and by 11.25–15.38% for NOB under 40 ppm and 80 ppm Cd stress, respectively. Leaf area (LA) and leaf area index (LAI) also showed reductions of 6.85–9.24%, and 4.88–6.37%, respectively, compared to the control conditions (Figs. 3A–E). Conversely, all concentrations of IAA improved growth parameters and mitigated the adverse effects of Cd stress. The most significant enhancements were observed at 200 µM IAA, which increased RL by 20.25–28.25%, SL by 35.68–45.68%, and NOL by 20–28.45% compared to the control. Under the highest Cd stress level (80 ppm), treatment with 200 µM IAA led to increase in root fresh weight (RFW) by 41–45%, root dry weight (RDW) by 33.21–37.52%, shoot fresh weight (SFW) by 16.75–19.65%, and shoot dry weight (SDW) by 25–29%. Additionally, improvements were recorded in NOB (14.5–17.5%), PH (35.25–40.25%), LA (6.75–9.87%), and LAI (13.25–16.85%) compared to control condition (Table 1, Figs. 2, 3).

Physiological attributes

Cd stress significantly decreased the total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b content in sorghum leaves. At Cd concentrations of 40 ppm and 80 ppm, total chlorophyll content decreased by 7.64–6.14%, chlorophyll a by 11.75–9.25%, and chlorophyll b by 11.50–8.25%, respectively, compared to the control. However, the application of 200 µM IAA significantly enhanced chlorophyll levels in Cd-stressed plants, with an increase of 14.17–16.19% in chlorophyll a, 11.75–15.25% in chlorophyll b, and 16.28–18.75% in total chlorophyll compared to control condition. These values were statistically similar to those observed under control conditions. Additionally, the chlorophyll a/b ratio improved significantly by 17.46–22.85% in plants treated with 200 µM IAA. In contrast, carotenoid concentrations did not show significant variation across treatment (Fig. 4A–E, Table 2).

Ionic, cadmium content

As Cd treatment increased, the Na+, K+, and Ca2+ concentrations in roots decreased significantly. Na+ levels decreased by 7.69–9.52%, K+ by 3.70–7.31%, and Ca2+ by 6.66–7.69% at 40 ppm and 80 ppm Cd compared to control conditions, respectively. However, the application of 150 or 200 µM IAA enhanced the ionic content in roots under Cd stress (80 ppm). The Na+ content increased by 11.53–35.47%, K+ by 14.52–53.66%, and Ca2+ by 17.64–48.22% with 200 µM IAA, compared to the control treatment (Fig. 5A–D).

Cadmium accumulation in roots was also significantly reduced by IAA treatment. Under Cd treatments of 40 ppm and 80 ppm, Cd content in roots decreased by 15% and 25%, respectively, when IAA was applied. The greatest reduction in Cd content was observed with 200 µM IAA, which reduced Cd accumulation by 11%, compared to the control treatment (Fig. 5D).

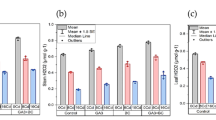

Enzymatic antioxidants

A significant interaction (P ≤ 0.05) between IAA treatments and Cd stress was observed for antioxidant enzyme activity. In comparison to the control, Cd stress at 80 ppm resulted in significant reductions in the activity of POD by 6.45–4.25%, CAT by 5–3%, superoxide SOD by 3.03–2.50% and ascorbate peroxidase APX by 5.37%. to 3.57% However, IAA application increased enzyme activity as compared to stressed plants. The highest concentration of IAA (200 µM) led to significant increases in POD (8.82%), CAT (10.06%), SOD (4.65%), and APX (17.94%) activities (Fig. 6A–D, Table 3).

Reactive oxygen species

Cd stress led to an increase in MDA content, a marker of lipid peroxidation, which was elevated by 4.94–6.37% at 40 ppm and 8.94–11.85% at 80 ppm Cd, compared to the control treatment. However, the application of IAA significantly reduced MDA content by 28.1–37.2% under 40 ppm Cd and by 35.5–39.1% under 80 ppm Cd stress compared to control conditions (Fig. 7A). Similarly, H2O2 content in roots increased by 6.98–8.1% at 40 ppm and 10.83–14.67% at 80 ppm Cd. The application of IAA significantly reduced H2O2 levels by 29.4–40.8% at 40 ppm and by 38.9–42.1% at 80 ppm Cd stress as compared to stress plant (Fig. 7B, Table 3).

Heat map

A heat map was constructed to examine the relationships between the morpho-physiological and biochemical traits of sorghum subjected to different Cd levels (Cd0: 0 ppm, Cd1: 40 ppm, Cd2: 80 ppm) and IAA concentrations (IAA0: 0 µM, IAA1: 50 µM, IAA2: 100 µM, IAA3: 150 µM, IAA4: 200 µM) (Fig. 8) . The main cluster was divided into three sub-clusters. H2O2 content in plants, grouped in the first sub-cluster, showed a positive association at Cd2IAA2, Cd2IAA3, and Cd2IAA4 but a negative association at Cd1IAA1 and Cd1IAA2. Similarly, MDA content exhibited a positive association at Cd0IAA2, Cd0IAA3, and Cd1IAA0, while showing a negative association at Cd2IAA1 and Cd2IAA4. All growth attributes (PH, LA, SL, NOB, NOL, RDW, RFW, RL, SFW, SDW), ionic attributes (Cd+, Na+, K+, Ca2+), photosynthetic parameters (Chl. a, Chl. b, T. Chl., chlorophyll ratio), and biochemical contents (SOD, POD, CAT, APX) were grouped in the third sub-cluster. These traits exhibited strong positive correlations at Cd0IAA3 and Cd0IAA4, but strong negative correlations at Cd2IAA0.

Heatmap representing the interaction of Sorghum morpho-physiological, Ros, enzymatic, and nutritional characteristics under Cd stress ) levels Cd0 (0 ppm), Cd1 (40 ppm), Cd2 (80 ppm) and IAA0 (0 µM), IAA1 (50 µM), IAA2 (100 µM), IAA3 (150 µM), IAA4 (200 µM), Car (Carotenoids), CAT (Catalase), Chl a (Chlorophyll a), Chl b (Chlorophyll b), ChlR (Chlorophyll ratio), H2O2. Hydrogen peroxide, MDA (malondialdehyde), NOB (number of branches), NOL (number of leaves), PH (plant height), LA (Leaf area), LAI (Leaf area index), POD (peroxidase), RCa2+ (root calcium), RDW (root dry weight), RFW (root fresh weight), RL (root length), RK (root potassium), RNa+ (root sodium), RCd2+, SFW (shoot fresh weight), SL (shoot length).

Principal component analysis (PCA)

Relationships among morpho-physiological and biochemical parameters of sorghum was assessed by PCA biplot (Fig. 9). The biplot revealed significant variation, with PCA1 accounting for 85.2% of the total variation and PCA2 contributing 8.2%. Plant MDA content was strongly associated with Cd1IAA2, while Cd0IAA0 showed a weak association with chlorophyll contents (chlorophyll a. chlorophyll b. carotenoids, and chlorophyll ratio) and biochemical parameters (SOD, POD, CAT, APX). These biochemical and chlorophyll contents, along with shoot fresh weight (SFW) and shoot dry weight (SDW), were linked to Cd1IAA3 and Cd1IAA4. Similarly, plant sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and cadmium (Cd2+) contents were positively associated with PH, RDW, NOL, RL, NOB, RFW and T. Chl., which were linked to Cd0IAA2 and Cd0IAA1. Plant hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content was strongly associated with Cd2IAA4.

PCA-Biplot of sorghum morphophysiological characteristics under cadmium stress. Carotenoids, Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, Chlorophyll ratio, Cd) levels Cd0 (0 ppm), Cd1 (40 ppm), Cd2 (80 ppm), NOB (Number of branches), NOL (Number of leaves), LA (Leaf area), LAI (Leaf area index) PH (Plant height), RDW (Root dry weight), RFW (Root fresh weight), RL (Root length), SDW (Shoot dry weight), IAA0 (0 µM), IAA1 (50 µM), IAA2 (100 µM), IAA3 (150 µM), IAA4 (200 µM), SFW (Shoot fresh weight), Shoot length (SL), TChl (Total chlorophyll), Na+, Ca2+, K+, RCd2+.

Correlations

The correlation among morpho-physiological and biochemical parameters of sorghum is presented in the (Fig. 10) Among all the measured chlorophyll parameters, including chlorophyll a (Chl. a), chlorophyll b (Chl. b), carotenoids, and total chlorophyll (T. Chl.), positive correlations were observed with ionic contents, (Ca2+, K+, Cd2+) as well as antioxidant contents, including SOD, POD, and CAT. Conversely, all these parameters showed a negative correlation with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

A correlation plot of sorghum morpho-physiological, enzymatic, ROS, and nutrient attributes during cadmium stress, including) Car (Carotenoids), CAT (Catalase), Chl a (Chlorophyll a), Chl b (Chlorophyll b), ChlR (Chlorophyll ratio), H2O2 (Hydrogen peroxide), MDA (malondialdehyde), NOB (Number of branches), NOL (Number of leaves), LA (Leaf area), LAI (Leaf area index), Plant Height, POD (Peroxidase), RCa2+ (Root calcium), RDW (Root dry weight), RFW (Root fresh weight), RK (Root potassium), RL (Root length), RNa+ (Root sodium), SDW (Shoot dry weight), SFW (Shoot fresh weight), SL (Shoot length), SOD (Superoxide dismutase).

Discussion

Plants are highly vulnerable to Cd toxicity, which disrupts key physiological processes like cell division, nutrient uptake, and photosynthesis. Cd primarily inhibits plant growth by inducing the production of ROS, causing oxidative stress that damages cellular structures and impairs normal function36. The exposure of sorghum to Cd at 40 ppm and 80 ppm led to significant reductions in RL, shoot SL, PH, and biomass. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating that Cd interrupts plant growth through multiple mechanisms8,11,15. Cd disrupts nutrient homeostasis by competing with essential micronutrients (Zn, Fe, Ca) for uptake, inducing deficiencies that exacerbate growth suppression. A critical example is Cd2+ substitution for Mg2+ in chlorophyll pigments, which impairs photosynthetic efficiency and leads to stunted shoot development36. Specifically, Cd at 80 ppm resulted in reduction of RL and SL by 35% and 28%, respectively, compared to the control, while total biomass decreased by 42%. Similar inhibitory effects of Cd on plant growth have been reported in recent studies. Previous researchers observed a 30–40% reduction in root elongation in wheat under Cd stress, attributed to oxidative damage and nutrient uptake interference37. Exogenous application of IAA mitigated Cd-induced growth inhibition, improving RL, SL, and biomass by 20–25% at 40 ppm Cd and 15–18% at 80 ppm Cd. This aligns with the findings of Yin et al.38, who reported that IAA enhances heavy metal tolerance by promoting auxin-mediated root development and antioxidant defense in Arabidopsis thaliana. Moreover, a study by Haider et al.39 demonstrated that IAA application alleviates Cd toxicity in Zea mays by improving photosynthetic efficiency and reducing oxidative stress. These results suggest that exogenous IAA plays a protective role against Cd stress in sorghum, potentially through mechanisms involving growth regulation, antioxidant activity, and metal ion homeostasis. The present study demonstrates that Cd stress significantly impairs sorghum growth, particularly in root development, as evidenced by reductions in root fresh weight (1.01–1.26%) and root dry weight (12.82–25%) at 40 ppm and 80 ppm Cd. These findings corroborate earlier reports highlighting Cd-induced growth suppression due to disrupted cell division, nutrient uptake inhibition, and oxidative damage38,40. The greater decline in RDW compared to RFW suggests that Cd preferentially affects metabolic activity and long-term biomass accumulation, consistent with observations in Oryza sativa41. Cd disrupts root growth by inhibiting meristematic activity like Cd interferes with auxin transport, reducing cell proliferation, inducing oxidative stress excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage cellular structures42,43. Exogenous application of IAA enhanced RFW by 45% and RDW by 37.52%, even under Cd stress. This aligns with studies showing that auxins IAA promotes lateral root formation, increasing absorptive surface area44. The present study clearly demonstrates that Cd stress significantly inhibits shoot growth in sorghum, as evidenced by reductions in SFW (8.16%) and SDW (16.34%) at elevated Cd concentrations (40–80 ppm). These findings align with previous studies showing that Cd disrupts shoot development by impairing photosynthesis, nutrient translocation, and biomass partitioning45. The greater reduction in SDW compared to SFW suggests that Cd not only limits water retention but also severely restricts metabolic activity and long-term carbon assimilation, consistent with observations in Zea mays46. By enhancing cell elongation, IAA promotes shoot expansion through the activation of plasma membrane H+-ATPases and the loosening of cell walls47. The application of exogenous IAA at 200 µM significantly improved shoot growth parameters in potatoes under Cd stress, with 18.75% increases in both shoot SFW and SDW compared to Cd-stressed controls. These findings highlight IAA’s potential as a phytohormonal mitigator of Cd toxicity, aligning with recent studies on auxin-mediated stress resilience in crops48. The detrimental effects of Cd stress on plant growth were evident in our study, with exposure to 80 ppm Cd resulting in significant reductions in plant height (10.62%), number of branches (15.38%), and number of leaves (8.96%). These findings align with previous research demonstrating Cd-induced growth inhibition across various plant species, including sassafras trees, where Cd stress similarly reduced morphological parameters such as plant height and leaf production, The observed declines in PH, NOB, and NOL can be attributed to Cd disruption of key physiological processes49. Our study revealed that Cd stress significantly reduced LA by 9.24% and leaf LAI by 6.37%, consistent with recent findings in multiple plant species. These reductions align with the work of50. who reported 8–12% decreases in LA in Cd-exposed Solanum lycopersicum due to inhibited cell expansion and reduced stomatal density. The LAI reduction is particularly noteworthy as it directly impacts photosynthetic capacity, as demonstrated by51. Our investigation demonstrated that exogenous application of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) significantly ameliorated cadmium-induced inhibition of leaf growth. Cadmium stress (80 ppm) reduced LA by 9.24% compared to control plants IAA treatment (200 μM) reversed this effect, increasing LA by 9.87% relative to Cd-stressed plants. The restored LA approached 98.2% of non-stressed control values. Cd exposure decreased LAI by 6.37%. IAA application enhanced LAI by 16.85% under Cd stress conditions. Treated plants showed 12.3% higher LAI than Cd-stressed controls. Our study confirms recent findings that Cd stress severely disrupts photosynthesis by reducing chlorophyll content. Cd replaces Mg2+ in chlorophyll pigments, destabilizing their structure, 38–45% chlorophyll reduction at 80 ppm Cd, Oryza sativa 25–30% reduction at similar concentrations52,53. Our results showed that 200 μM IAA restored 45–50% chlorophyll pigments which is supported by multiple recent studies elucidating auxin’s role in all photosynthetic pigments51,52. Our study demonstrates that cadmium stress significantly disrupts ionic homeostasis in plants, with observed reductions in essential nutrient uptake at both 40 ppm and 80 ppm Cd concentrations. Specifically, Na+ levels decreased by 7.69–9.52%, Ca2+ by 6.66–7.69%, and K+ by 3.70–7.31%, consistent with previous findings in Acacia nilotica where Cd was shown to competitively inhibit nutrient transporter activity54. These ionic imbalances are particularly detrimental as Ca2+ serves as a crucial secondary messenger in stress signaling55. The remarkable recovery of ionic balance through 200 µM IAA application, with Na+ increased from 11.53–35.47%, Ca2+ from17.64–48.22%, and K+ from 14.52–53.66%, can be attributed to multiple mechanisms recently elucidated in plant physiology research. These results have important agronomic implications, as maintaining ionic balance is critical for crop yield under heavy metal stress. The 200 µM IAA concentration proved optimal in our study, corroborating the dose–response curve established by Shahid et al.56.

Cadmium treatment markedly reduced SOD, POD, and CAT enzyme activities in wheat leaves, consistent with reported inhibitory effects of Cd stress on antioxidant enzymes across plant species57. Our findings revealed that elevated Cd levels (40 ppm and 80 ppm) significantly inhibited the activation of critical enzymatic functions. Exogenous application of IAA at 200 µM was found to significantly increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes in sorghum, thereby alleviating Cd-induced oxidative stress. Similar observations were reported by Bashri et al.58 who demonstrated enhanced APX activity in Vicia sativa and Hordeum vulgare under Cd stress, which contributed to improved metal tolerance. In maize cultivars, Cd exposure likewise increased APX activity59. However, contrasting responses have been documented in Brassica species while SOD and CAT activities were suppressed in B. napus under Cd stress, APX activity was upregulated in both B. napus and B. juncea60. Interestingly, Cd-sensitive pea genotypes showed reduced APX activity. In our study, Cd stress (80 ppm) inhibited APX activity by 3.57% compared to control plants. However, IAA application at 150 µM and 200 µM not only reversed this suppression but also increased APX activity by 17.94–25.56%, exceeding control levels. Furthermore, IAA treatment directly reduced ROS accumulation in Cd-stressed explants. These findings align with previous reports suggesting that Cd toxicity disrupts antioxidant enzyme systems by inducing ROS overproduction61. Cadmium induces oxidative stress in plants, leading to significant impairments in growth and development62. Plant tolerance to heavy metal toxicity is strongly correlated with the efficacy of their antioxidant defense systems. In sorghum, Cd exposure at 40–80 ppm was found to elevate oxidative stress markers, increasing malondialdehyde (MDA) content by 4.94–6.37% and H2O2 levels by 8.94–11.85% in root tissues. However, treatment with 200 μM IAA significantly ameliorated this oxidative damage, reducing MDA levels by 29.4–40.8% and H2O2 accumulation by 38.9–42.1%. This marked reduction in oxidative markers highlights IAA’s protective role in alleviating Cd toxicity in sorghum plants63.

Conclusion

This study examined how IAA affects on sorghum under Cd stress. Different IAA concentrations (0–200 µM) and Cd levels (0–80 ppm) were tested. IAA significantly accumulated in plant tissues, with increases of 28.25% in roots and 45.68% in shoots. IAA improved nutrient uptake, including Cd, Na+, K+, and Ca2+, enhancing turgor and physiological responses. Ionic content increased up to 68.63% with IAA treatment. ROS levels were reduced by 29.4% following IAA application. IAA enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities: SOD (4.65%), POD (8.82%), CAT (10.06%), and APX (17.9%). Harmful ROS markers, MDA and H2O2, decreased by 40.8–42.1%, respectively. Overall, IAA improved plant growth and stress resilience under Cd toxicity. Further research is needed to uncover the molecular basis of these effects.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- RL:

-

Root length

- SL:

-

Shoot length

- RFW:

-

Root fresh weight

- SFW:

-

Shoot fresh weight

- RDW:

-

Root dry weight

- NOB:

-

No. of branches

- LIA:

-

Leaf area index

- SDW:

-

Shoot dry weight

- NOL:

-

No of leaves

- LI:

-

Leaf area

- PH:

-

Plant height

- chl a :

-

Chlorophyll a

- chl b :

-

Chlorophyll b

- chl a/b :

-

Chlorophyll a/b

- chl a/b :

-

Chlorophyll a/b ratio

- Car:

-

Carotenoids

- Na+ :

-

Sodium ions

- Ca2+ :

-

Calcium ions

- K+ :

-

Potassium ions

- Cd2+ :

-

Cadmium ions

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- POD:

-

Peroxidase

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- APX:

-

Ascorbate peroxidase

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- H2O2 :

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- * and **:

-

Significant at P ≤ 0.01% and P ≤ 0.001%, respectively, ns = P > 0.05%

References

Hao, H. et al. Sorghum breeding in the genomic era: opportunities and challenges. Theor. Appl. Genet. 134, 1899–1924 (2021).

Stamenković, O. S. et al. Production of biofuels from sorghum. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Rev. 124, 109769 (2020).

Kazungu, F. K., Muindi, E. M. & Mulinge, J. M. Overview of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), its economic importance, ecological requirements and production constraints in Kenya. Int. J. Plant & Soil Sci. 35, 62–71 (2023).

Kazungu, F. Growth and yield potential of sorghum as influenced by manure and inorganic fertilizer in post mined soils (Pwani University, 2022).

Guo, J. et al. Transcriptome and GWAS analyses reveal candidate gene for seminal root length of maize seedlings under drought stress. Plant Sci. 292, 110380 (2020).

Birhanu, S. Potential benefits of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] on human health: A Review. I. J. Food. Eng. Tech. 5, 16–26 (2021).

Ali, H., Khan, E. & Ilahi, I. Environmental chemistry and ecotoxicology of hazardous heavy metals: Environmental persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation. J. Chem. 2019, 6730305 (2019).

Genchi, G., Sinicropi, M. S., Lauria, G., Carocci, A. & Catalano, A. The effects of cadmium toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 3782 (2020).

Abedi, T. & Mojiri, A. Cadmium uptake by wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): An overview. Plants 9, 500 (2020).

Kubier, A., Wilkin, R. T. & Pichler, T. Cadmium in soils and groundwater: A review. Appl. Geochem. 108, 104388 (2019).

Rizwan, M., Ali, S., Rehman, M. Z. U. & Maqbool, A. A critical review on the effects of zinc at toxic levels of cadmium in plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 6279–6289 (2019).

Ben Mrid, R., Bouargalne, Y., El Omari, R., El Mourabit, N. & Nhiri, M. Activities of carbon and nitrogen metabolism enzymes of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) during seed development. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 21, 283–289 (2018).

Silambarasan, S., Logeswari, P., Vangnai, A. S., Kamaraj, B. & Cornejo, P. Plant growth-promoting actinobacterial inoculant assisted phytoremediation increases cadmium uptake in Sorghum bicolor under drought and heat stresses. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 119489 (2022).

Roussi, Z. et al. Insight into Cistus salviifolius extract for potential biostimulant effects in modulating cadmium-induced stress in sorghum plant. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 28, 1323–1334 (2022).

Jiang, Y., Huang, R., Jiang, S., Qin, Z. & Yan, X. Adsorption of Cd (II) by rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil originating from mulberry field under laboratory condition. Int. J. Phytorem. 20, 378–383 (2018).

Kumar, P., Pathak, S., Kumar, M. & Dwivedi, P. In: Biotechnological Approaches for Medicinal and Aromatic Plants 199–212 (Springer, 2018).

Jamla, M. et al. Omics approaches for understanding heavy metal responses and tolerance in plants. Curr. Plant Biol. 27, 100213 (2021).

Sytar, O., Ghosh, S., Malinska, H., Zivcak, M. & Brestic, M. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of metal accumulation in hyperaccumulator plants. P Physiol. Plant. 173, 148–166 (2021).

Emenecker, R. J. & Strader, L. C. Auxin-abscisic acid interactions in plant growth and development. Biomolecules 10, 281 (2020).

Meliani, A., Bensoltane, A., Benidire, L. & Oufdou, K. Plant growth-promotion and IAA secretion with Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida. Research & Reviews: J. Bot. Sci. 6, 16–24 (2017).

Babiye, B. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) Production from Sorghum Rhizosphere bacteria in Ethiopia.

Gizaw, W. & Assegid, D. Trend of cereal crops production area and productivity. Ethiopia. J. Cereals. Oilseeds. 12, 9–17 (2021).

Biswas, S. et al. Study on the activity and diversity of bacteria in a New Gangetic alluvial soil (Eutrocrept) under rice-wheat-jute cropping system. J. Environ. Biol. 39, 379–386 (2018).

Rostami, S. & Azhdarpoor, A. The application of plant growth regulators to improve phytoremediation of contaminated soils: A review. Chemosphere 220, 818–827 (2019).

Singh, P., Singh, I. & Shah, K. Alterations in antioxidative machinery and growth parameters upon application of nitric oxide donor that reduces detrimental effects of cadmium in rice seedlings with increasing days of growth. S. Afr. J. Bot. 131, 283–294 (2020).

Arnon, D. I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant. Physiol. 24, 1 (1949).

Wolf, B. A comprehensive system of leaf analyses and its use for diagnosing crop nutrient status. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 13, 1035–1059 (1982).

Chen, B. et al. The effects of the endophytic bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Sasm05 and IAA on the plant growth and cadmium uptake of Sedum alfredii Hance. Front. microbiol. 8, 2538 (2017).

Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutases. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 58, 61–97 (1986).

David, R. & Murray, E. Protein synthesis in dark-grown bean leaves. Can. J. Bot 43, 817–824 (1965).

Agarwal, S., Sairam, R., Srivastava, G., Tyagi, A. & Meena, R. Role of ABA, salicylic acid, calcium and hydrogen peroxide on antioxidant enzymes induction in wheat seedlings. Plant Sci. 169, 559–570 (2005).

de Cássia Alves, R. et al. Exogenous foliar ascorbic acid applications enhance salt-stress tolerance in peanut plants through increase in the activity of major antioxidant enzymes. S. Afr. J. Bot. 150, 759–767 (2022).

Asghar, N. et al. Foliar-applied hydrogen peroxide and proline modulates growth, yield and biochemical attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Under varied n and p levels. Fresenius. Environ. Bull. 30, 5445–5465 (2021).

Morales, M. & Munné-Bosch, S. Malondialdehyde: facts and artifacts. Plant. Physiol. 180, 1246–1250 (2019).

Steel, R. G. D. & Torrie, J. H. Principles and procedures of statistics, a biometrical approach (McGraw-Hill Kogakusha Ltd., 1980).

Rizwan, M. et al. Cadmium minimization in wheat: a critical review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 130, 43–53 (2016).

Mohsin, S. M., Hasanuzzaman, M., Parvin, K., Shahadat Hossain, M. & Fujita, M. Protective role of tebuconazole and trifloxystrobin in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under cadmium stress via enhancement of antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 27, 1043–1057 (2021).

Yin, K. et al. Populus euphratica CPK21 interacts with heavy metal stress-associated proteins to mediate Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Stress 11, 100328 (2024).

Haider, F. U., Khan, I., Farooq, M., Cai, L. & Li, Y. Co-application of biochar and plant growth regulators improves maize growth and decreases Cd accumulation in cadmium-contaminated soil. J. Cleaner. Prod. 440, 140515 (2024).

Kaya, C., Akram, N. A. & Ashraf, M. Kinetin and indole acetic acid promote antioxidant defense system and reduce oxidative stress in maize (Zea mays L.) plants grown at boron toxicity. J. Plant Growth Regul. 37, 1258–1266 (2018).

Wang, T. et al. Mutation at different sites of metal transporter gene OsNramp5 affects Cd accumulation and related agronomic traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1081 (2019).

Cui, T. et al. Auxin alleviates cadmium toxicity by increasing vacuolar compartmentalization and decreasing long-distance translocation of cadmium in Poa pratensis. J. Plant Physiol. 282, 153919 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Activation of integrated stress response and disordered iron homeostasis upon combined exposure to cadmium and PCB77. J. Hazard. Mater. 389, 121833 (2020).

Abbas, S. et al. In vitro exploration of Acinetobacter strain (SG-5) for antioxidative potential and phytohormone biosynthesis in maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars differing in cadmium tolerance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 45465–45484 (2024).

Khan, I. et al. New insights into phytohormones (IntechOpen, 2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Synergistic effects of exogenous IAA and melatonin on seed priming and physiological biochemistry of three desert plants in saline-alkali soil. Plant Signaling Behav. 19, 2379695 (2024).

Luo, P., Li, T.-T., Shi, W.-M., Ma, Q. & Di, D.-W. The roles of GRETCHEN HAGEN3 (GH3)-dependent auxin conjugation in the regulation of plant development and stress adaptation. Plants 12, 4111 (2023).

Luo, W.-G. et al. Auxin inhibits chlorophyll accumulation through ARF7-IAA14-mediated repression of chlorophyll biosynthesis genes in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1172059 (2023).

Huihui, Z. et al. Toxic effects of heavy metals Pb and Cd on mulberry (Morus alba L.) seedling leaves: Photosynthetic function and reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 195, 110469 (2020).

Eichenberg, D. et al. Widespread decline in Central European plant diversity across six decades. Global Change Biol. 27, 1097–1110 (2021).

Pradeep, K. Improving heavy metal stress tolerance in tomato by grafting. (2015).

Shah, N. et al. Enhancement of cadmium phytoremediation potential of Helianthus annuus L. with application of EDTA and IAA. Metabolites 12, 1049 (2022).

Ran, J., Zheng, W., Wang, H., Wang, H. & Li, Q. Indole-3-acetic acid promotes cadmium (Cd) accumulation in a Cd hyperaccumulator and a non-hyperaccumulator by different physiological responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 191, 110213 (2020).

Nazar, R. et al. Cadmium toxicity in plants and role of mineral nutrients in its alleviation. Am. J. Plant Sci. 3, 1476–1489 (2012).

Manishankar, P., Wang, N., Köster, P., Alatar, A. A. & Kudla, J. Calcium signaling during salt stress and in the regulation of ion homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 4215–4226 (2018).

Shahid, M. et al. Heavy metal stress and crop productivity. In Crop production and global environmental issues (ed. Hakeem, K.) (Springer, Cham, 2015).

Guo, J. et al. Cadmium stress increases antioxidant enzyme activities and decreases endogenous hormone concentrations more in Cd-tolerant than Cd-sensitive wheat varieties. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 172, 380–387 (2019).

Bashri, G. & Prasad, S. M. Exogenous IAA differentially affects growth, oxidative stress and antioxidants system in Cd stressed Trigonella foenum-graecum L. seedlings: Toxicity alleviation by up-regulation of ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 132, 329–338 (2016).

Sitko, K. et al. The relations between the effect of Cd and Pb on the growth of maize seedlings, and their IAA and H2O2 content. BioTechnologia. J. Biotechnol. Comput. Biol. Bionanotechnol 94, 2 (2013).

Wu, Z. et al. Antioxidant enzyme systems and the ascorbate–glutathione cycle as contributing factors to cadmium accumulation and tolerance in two oilseed rape cultivars (Brassica napus L.) under moderate cadmium stress. Chemosphere 138, 526–536 (2015).

Li, S.-W., Leng, Y., Feng, L. & Zeng, X.-Y. Involvement of abscisic acid in regulating antioxidative defense systems and IAA-oxidase activity and improving adventitious rooting in mung bean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] seedlings under cadmium stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 21, 525–537 (2014).

Singh, S. & Prasad, S. M. IAA alleviates Cd toxicity on growth, photosynthesis and oxidative damages in eggplant seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 77, 87–98 (2015).

Sakouhi, L., Hussaan, M., Murata, Y. & Chaoui, A. Role of calcium signaling in cadmium stress mitigation by indol-3-acetic acid and gibberellin in chickpea seedlings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 16972–16985 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP 2/216/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB and MSU collected data and drafted paper, AM, and MMJ; Conception and supervised during writing andarrangements of data; MS, SHQ, FAA, and MH Application of software, and editing of draft, AM, FAA, MH, MS, MMJ, MAN and SHQ Revised manuscriptcritically for intellectual content, AM, FAA and MH; Final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of thiswork.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All Authors have provided consent to publish the data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bibi, A., Ullah, M.S., Mahmood, A. et al. Indole-3-acetic acid improves growth, physiology, photosynthesis, and ion balance under cadmium stress in Sorghum bicolor. Sci Rep 15, 33971 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10900-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10900-7