Abstract

In this study the effect of silica nanoparticles (SCN) concentration on cellulose/silica nanocomposite prepared by sol/gel technique in the presence of acid and base catalyst were investigated. The cellulose was extracted form sugarcane bagasse (RSB). The nanocomposites (SCN 0.6 g, 0,8 g and 1 g) were prepared by the sol-gel method using ammonium solution and hydrochloric acid as catalysts. FTIR results showed that peak intensities were increased with the addition of nano silica on cellulosic fibres under alkaline catalyst influence as compared to acid catalyst due to an increased in concentrations of −OH group and reduction in hydrogen bond of SCN. XRD results confirm that the incorporation of nano silica did not necessarily change the crystallinity of cellulose fibres. In addition, the HCl catalyzed nano silica nanocomposites exhibited higher crystallinity index compared to the ammonium catalyzed nanocomposites. The thermal stability of SCN was increased with the presence of silica, even though most of high concentrations seemed to decrease. SEM analyses revealed that the diameter of the extracted cellulose was increased with an increase of the silica content. Moreover, the diameter increase was greater in acid catalysed as compared to base catalysed nanocomposites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The preparation of silica nanoparticles is a pivotal area in nanotechnology, with methods such as microemulsion, precipitation, laser ablation, and the sol-gel technique taking centre stage. Among those, the sol-gel method stands out for its versatility and efficacy in research applications. The method is known to produce silica nanoparticles in the 10 to 500 nm size range, available in diverse shapes like nanorods and nanospheres. By fine-tuning parameters such as temperature, reaction time, and concentration, researchers can precisely control the morphology and size of nanoparticles. Silica nanoparticles are categorized as either non-porous or porous based on their structural and functional characteristics, making them indispensable in industrial applications such as thermal insulation, electronics, mechanical materials, and ceramics due to their high surface area and porosity1,2. Another beneficial application the nanoparticles is to blend it with cellulose to produce competent cellulose/silica nanocomposites with hybridised properties for diverse applications including medicinal strips and filterable membranes3,4.

In fact, the integration of silica nanoparticles into cellulose fibres significantly enhances the mechanical properties of the nanocomposites, leading to improved Young’s modulus and tensile strength3. Additionally, silica nanoparticles bolster the thermal stability and resistance to fungal decay of the nanocomposites. The enhancement is crucial as cellulose fibres typically lose mechanical properties when exposed to moisture3,4,5. Actually, the addition of silica nanoparticles mitigates the issue of mechanical properties, increasing the hardness and lipophilicity of cellulose/silica nanocomposites6. That is why is also applied in fields such as water treatment, drug delivery, and as electrical and thermal conductors6,7.

The sol-gel technique is an advanced and highly efficient method for preparing nanocomposites. Starting with liquid precursors that interact to form a homogeneous system, this technique allows for the creation of organic-inorganic hybrid nanocomposites with superior properties compared to purely inorganic materials8. The sol-gel method is particularly advantageous for preparing cellulose/silica nanocomposites because it offers precise control over porosity, shape, size, and material properties9. During this process, silica nanoparticles are embedded within a cellulose matrix, forming strong hydrogen bonds that enhance the composite’s integrity. The choice of catalyst and synthesis conditions is critical in determining the final properties of these nanocomposites10.

Catalysts are essential in the sol-gel process for cellulose/silica nanocomposites, facilitating the necessary condensation and hydrolysis reactions. The type of catalyst used can profoundly affect reaction kinetics, morphology, nanoparticle size, and composite properties11. For instance, base catalysts like ammonia are known to influence pH of a solution, cellulose solubility, silica hydrolysis and condensation rates, as well as the dispersion of silica nanoparticles4,12. On the other hand, acid catalysts such as hydrochloric acid significantly improve thermal stability, control particle size, and enhance the homogeneity of silica nanoparticles within the cellulose matrix. However, using strong mineral acids such as nitric acid and sulfuric acid can sometimes damage the polymer matrix during aerogel drying4,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33.

Prior research has highlighted the significant impact of varying silica concentrations and synthesis conditions on the properties of cellulose/silica nanocomposites. For example, Soemphol et al. demonstrated that a 9% silica concentration, prepared using sulfuric acid, achieved optimal thermal stability13. Similarly, Ashori et al. found that both mechanical properties and press time are crucial, with specific formulations showing maximum improvements in performance14.

This study aims to push the boundaries of current research by preparing cellulose/silica nanocomposites using both acid and base catalysts, specifically hydrochloric acid, and ammonia. We utilized cellulose extracted from sugarcane bagasse, an agricultural waste product, and silica nanoparticles derived from silica fume. The nanocomposites were prepared at room temperature over 24 h using the sol-gel technique with varying silica concentrations (0.6, 0.8, and 1 g). The resulting samples were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA).

Materials and methods

Materials

Materials

Raw sugarcane bagasse used in the study was supplied by Tongaat-Hullet Sugar Company in Felixton, Empangeni, Kwazulu-Natal in South Africa.

Chemicals

Sodium hydroxide pellets (NaOH) 99.9%, sodium chlorite (ClNaO2) 80%, glacial acetic acid (CH3COOH), ammonia solution (NH3) 25%, hydrochloric acid (HCl) 32%,ethanol (CH3CH2OH) 99.9%, tetraethoxyorthosilicate (TEOS). These chemicals were purchased at Merck Chemicals and Prestige laboratory supplier at Mount Edgecombe in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Preparations

Cellulose extraction

Sugarcane bagasse was first washed twice with distilled water to remove adhering soil and surface impurities. The cleaned material was then oven-dried at 70 °C for 24 h to eliminate residual moisture. The dried bagasse was subsequently subjected to an alkali treatment using 4 wt% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution. This treatment was carried out twice, each time for 1 h, to remove hemicellulose and other non-cellulosic components. After the alkali treatment, the bagasse was rinsed thoroughly and dried in an oven at 55 °C for 24 h.

The alkali-treated bagasse was then bleached to further purify the cellulose. Bleaching was conducted using a buffer solution composed of 27 g of NaOH and 75.00 mL of glacial acetic acid, diluted to a final volume of 1.00 L with distilled water. The bleaching process was carried out at 80 °C for 1 h and repeated twice to ensure effective delignification. The resulting cellulose was filtered and washed repeatedly with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved, indicating the removal of residual chemicals. Finally, the purified cellulose was oven-dried at 55 °C for 24 h and stored for further use. This treatment sequence ensured the efficient isolation of high-purity cellulose from sugarcane bagasse. The same extraction method was utilized in another study, in which quantitative analyses were conducted30.

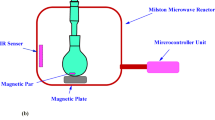

Silica nanoparticle extraction

The sol-gel-derived nano-silica was synthesized using a previously reported method31,32,33. Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS; 0.76 mL, liquid form, Sigma–Aldrich, Krugersdorp, South Africa) was used as the precursor. To this, 3.0 mL of water and 4.0 mL of acetone (Laboratory Consumables and Chemical Suppliers, Durban, South Africa) were added, maintaining a molar ratio of 1:4:4 (TEOS: water: acetone). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5–7 h to facilitate hydrolysis and polycondensation. The resulting polysilanol precipitates glassy, spherical nanoparticles dispersed in a sol were referred to as nano-silica.

A mass of 5 g of silica was mixed with 100.00 mL of 2.5 M NaOH aqueous solution. The mixture was heated at 80 °C for 30 min under stirring using the magnetic stirrer bar. The mixture was then filtered under the Whatman paper to remove all the insoluble solids. The filtrate was collected and titrated with 2.5 M H2SO4 to maintain the pH of 8-8.5. The formed silica gel was washed with distilled water several times to remove the sodium sulphate. After washing with distilled water, the dilute NaOH was added to maintain the pH that ranges from 8.5 to 10.5. The obtained silica gel was converted to colloidal nano-silica using the ultrasonic waves at 30 W and 20 kHz in the period of 60 min.

Silica-cellulose nanocomposite synthesis

Method 1

The silica nanoparticles of different quantities were added in three different flasks (0.6, 0.8 and 1 g of silica nanoparticles) the cellulose fibres were added in the same flask. The concentrated ammonia solution catalyst was added drop wise, followed by addition of distilled water and ethanol, this was done under stirring at room temperature for 24 h. The silica/cellulose nanocomposite obtained were filtered and dried at 50 °C.

Method 2

The silica nanoparticles of different quantities were added in three different flasks (0.6, 0.8 and 1 g of silica nanoparticles) the cellulose fibres were added in the same flask. The hydrochloric acid solution catalyst was added drop wise, followed by addition of distilled water and ethanol, this was done under stirring at room temperature for 24 h. The silica/cellulose nanocomposite obtained were filtered and dried at 50 °C.

Characterization methods

Scanning electron microscopy

The Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) measurements of samples were carried out on a FEI Quanta 200 electron microscopy operated at an accelerating voltage of 20KV. The samples were carbon-coated before the analysis using Edward’s E306A coating system. Three SEM micrographs were captured from different regions of the sample to assess the surface morphology at 10 and 100 micrometre (µm).

Fourier transform infrared

Fourier transform infra-red (FTIR) analysis of samples were performed using a Perkin Elmer attenuated total reflection FTIR spectrometer (Perkin Elmer UATR Two) operated in the diffuse reflectance mode. The spectral region between 4000 and 500 cm− 1 was used during sample analysis. Each sample was tested three times to ensure reproducibility and reliability of the results.

X-ray diffraction

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) were characterized on a Bruker AXS Advance D8 diffractometer, Karsruhe, Germany equipped with monochromatic Cu Kα (λ = 1.5406 Å) as X-ray source operating at 40 KV, 40 mA and rate of 0.5° min− 1 at room temperature. Each sample was analysed three times to ensure reproducibility and reliability of the results.

The crystallinity index (CI) was computed using both the Segal empirical method and deconvolution method. The Segal empirical method is calculated from the height of I002 and the height of Imin between the 002 peak and the 001 peak. The CI was calculated using the method below.

where, I002 denotes the maximum intensity of diffraction of the 002 peak while Iam denotes the intensity of diffraction of the amorphous material15.

Using the deconvolution method, the CI is determined using the ratio of the area of all crystalline peaks to the total area.

where, Acryst denotes the area of crystalline domain and Aamorp denotes the area of the amorphous domain.

Thermogravimetric analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of samples was conducted using TGA analyser (Perkin Elmer Pyris 6). Samples ranging from 10 to 15 mg were heated at a temperature range 35–900 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C per minute under nitrogen environment at a flow rate of 20 ml.min− 1. Each sample was tested three times to ensure reproducibility and reliability of the results.

Results and discussion

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Figure 1a illustrates cellulose fibres, Fig. 1b nano-silica, Fig. 1c SCN composite with 0.6 g nano-silica using an ammonium catalyst, Fig. 1d SCN composite with 0.6 g nano-silica using an HCl catalyst, Fig. 1e SCN composite with 1.0 g nano-silica using an ammonium catalyst, and Fig. 1f SCN composite with 1.0 g nano-silica using an HCl catalyst. Table 1 provides a summary of the observed trends in fibre diameter.

Figure 1a clearly shows that the morphology of the extracted cellulose was influenced by the alkali treatment, which removed hemicellulose and lignin, resulting in increased whiteness of the cellulose. The SEM analysis confirms the defibrillation process and reveals that the diameters of the fibres range from 7 to 12 μm. The image (Fig. 1b) of nano silica clusters (ranging from 1 to 20 μm) shows various nanoparticles adhered and uniformity to potentially make a large surface area.

In comparing the basic and acidic catalysts, it is nearly impossible to observe nano-silica particles on the cellulose fibres due to the low silica content in both treatments. That may suggest a strong interaction which dispersed silica particles on the cellulose fibrils. However, for the high contents of silica there was what looked like thin layers (see the arrow) wrapped around the fibrils. Furthermore, there was a clear increase in diameter of silica nanocomposites with the content of silica (See Tabe 1). This suggested that silica particles saturated the interior of fibrils and covered the fibres. The observation is more pronounced for the HCL treated composites, likely due to the catalytic role of HCl in facilitating the hydrolysis and condensation of silica precursors. The acidic environment may promote a higher degree of silanol group formation, enhancing the interaction between silica species and the cellulose matrix. Consequently, this leads to more extensive silica deposition, resulting in observable morphological changes such as increased fibre diameter and surface roughness (See Fig. 1c–f)).

In fact, when the silica concentration increases, the extracted cellulose becomes more uniformly thicker, and the diameter of almost all fibres increases. This phenomenon is known as the formation of hydrogen bonds between extracted cellulose and silica due to the abundance of hydroxyls on the cellulose microfibers16,17. In this study that could also be responsible to the formation of covers of silica around some fibrils at the high contents. The silanol groups on nano silica bonds to the hydroxyl group on the surface of cellulose via a hydrogens bond and this causes better adhesion and increased thermal stability. Also, the acid catalyst cleaves some cellulosic crystallinity, reviling more -OH functional groups thus increasing the reacting sites, the surface area and the interaction of silica and cellulose is also increased16,17,18. This suggests that silica particles not only penetrated and saturated the interior of the fibrils but also formed a coating on the fibre surfaces.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR spectra of SCN (0.6 g, 0.8 g and 1 g) under the influence of different catalyst (ammonia base and hydrochloric acid) are illustrated in Fig. 2a and b), respectively.

The RSB spectrum showed a broad peak at 3335 cm− 1 associated with the hydroxyl (-OH) group found in lignocellulosic biomass materials. The peaks at 2895 cm− 1 and 1733 cm− 1 represent the CH- methylene stretching, and the carbonyl stretching (–C= O) of acetal groups found in cellulose and hemicellulose, respectively. There were also notable peaks at 1628 cm− 1 and 1516 cm− 1 indicating the C =O stretching and phenyl stretching found in lignin biomass. The peaks at 1425 cm− 1 and 1363 cm− 1 represent the CH2 asymmetric stretching and CH bend found in cellulose and lignin, respectively. In addition, the peaks at 1230 cm− 1, 1161 cm− 1 and 1035 cm− 1 indicate the C–O stretching, C–O–C asymmetrical stretching and C-O stretching found in cellulose and hemicellulose18,19. The cellulose spectrum displayed almost similar pattern as RSB graph. However, it can be observed that the cellulose peaks were enhanced due to the removal of non-cellulosic components like lignin, pectin and hemicellulose. The peak at 1516 cm− 1, 1230 cm− 1 and 830 cm− 1 attributed to the presence of lignin and hemicellulose were noticeably absent nor reduced in the cellulose spectrum20,21,22,23,24. The extracted nano silica spectrum showed typical major peaks at 1069 cm− 1 and 782 cm− 1 associated with asymmetric and symmetric vibration of Si–O–Si, respectively23.

From Fig. 2a, the cellulose and SCN (0.6 g, 0.8 g and 1 g) exhibited almost similar trends. The SCN spectra showed the broad peaks at 3200–3500 cm− 1 and 1000–1070 cm− 1 associated with the hydroxyl group and Si–OH asymmetric vibrations, respectively. The peaks at 1260 cm− 1, 1200 cm− 1 and 1069 cm− 1 were associated with Si-CH3 to silica backbone, Si–O–C and incorporation of methyl group in Si–O–Si, respectively25. The SCN (0.6 g) spectrum showed a noticeable decrease of peaks at 3200–3500 cm− 1 indicating the incorporation of extracted nano silica disrupted the O–H stretching on cellulose surface. The peaks at 2900 cm− 1, 1632 cm− 1 and 1317 cm− 1 associated with CH2 stretching in cellulose and C-O stretching vibration in cellulose were reduced as extracted nano silica was added. Moreover, the peak at 1744 cm− 1 was elongated indicating interaction between extracted nano silica and –C =O of ester group20,26. The SCN (0.8 g and 1 g) spectra showed an increase in intensity peaks at 3400 cm− 1, 2900 cm− 1, 1632 cm− 1 and 1317 cm− 1 with an increase in extracted nano silica content. The elongation of the 1744 cm− 1 peak suggests strong interactions between extracted nano silica and the ester carbonyl (–C= O) groups, likely through hydrogen bonding with surface silanol (Si–OH) groups. This interaction enhances the dipole moment, increasing IR absorption. The decrease in intensity at 2900, 1632, and 1317 cm− 1 is attributed to the disruption of cellulose’s hydrogen bonding network, dilution of functional groups, or shielding by silica particles. Additionally, in this study, the observed changes could be attributed to ammonia’s ability to promote hydrogen bonding between cellulose and extracted nano silica, thereby modifying the cellulose structure. However, the peaks at 1744 cm⁻¹ decreased in both spectra27, suggesting reduced ester carbonyl interactions. This may be due to structural rearrangement or partial disruption of ester groups during ammonia treatment. In fact, this observation aligns with the increased surface area seen in the SEM images of the ammonia-treated composites, supporting the notion that ammonia enhances interfacial interaction while altering the original cellulose–silica bonding environment.

From Fig. 2b, the FTIR spectra of SCN samples (0.6 g, 0.8 g, and 1 g) followed a similar trend to that of pure cellulose, indicating the preservation of major cellulose functional groups. The spectrum for SCN (0.6 g) showed a noticeable reduction in the intensity of characteristic peaks at 3400 cm− 1 (O–H stretching), 2900 cm− 1 (C–H stretching), 1632 cm− 1 (adsorbed water), and 1317 cm− 1 (C–H bending). Notably, the peaks at 2971 cm− 1 and 1213 cm− 1 were significantly diminished, suggesting the interaction or partial replacement of cellulose functional groups due to the attachment of nano-silica.A new absorption band appeared at 795 cm− 1, which is attributed to Si–O–Si stretching vibrations, confirming the successful incorporation of nano-silica onto the cellulose surface. This band is associated with hydrogen bonding between silica nanoparticles and cellulose hydroxyl groups27. The SCN (0.8 g) sample exhibited enhanced peak intensities, indicating increased silica content, while SCN (1 g) displayed a reduction in intensity, likely due to surface saturation or particle agglomeration27,28,29. Comparing Figs. 2a and b, it is evident that the incorporation of nano-silica influenced the spectra differently depending on the catalyst used. Under ammonia catalysis, the FTIR spectra showed enhanced peak intensities with increasing nano-silica content, whereas spectra under hydrochloric acid catalysis exhibited a general decline in peak intensities with silica addition. This suggests that the acidic and basic environments affected the interaction between cellulose and silica differently. Specifically, under acid catalysis, the 2970 cm− 1 peak decreased progressively with silica loading, while under ammonia catalysis, this peak was absent at 0.8 g and 1 g SCN loadings. These observations imply differing modes of silica incorporation onto cellulose fibres, which were also supported by SEM analysis. The variation in transmittance and peak behavior reflects the extent of silica saturation and bonding on the cellulose fibrils.

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD)

Figure 3a presents the XRD spectra of the extracted nano-silica; Fig. 3b shows the spectra of RSB, extracted cellulose, and SCN (0.6 g, 0.8 g, and 1.0 g) treated with a basic catalyst; while Fig. 3c illustrates the corresponding spectra under the influence of an acidic catalyst.

Crystalline index values of materials were studied using Segal and deconvolution methods under the influence of ammonia(base) and hydrochloric acid (Acid) catalysts are in Table 2. The XRD spectra for nano silica exhibited peaks at 2θ = 19.38°, 23.51°, 28.43°, 29.41°, 32.48°, 34. 24°, 38.98°, 49.13°, 54.98° and 59.75° which are typical for silica16. The RSB and cellulose spectra showed typical lignocellulosic biomass pattern with the main peaks observed at 2θ = 15°, 23° and 35°. In fact, the removal of all non-cellulosic components in RSB rendered pronounced intensities for peaks of the cellulose as confirmed by CI values in Table 213. For both catalysts there was increased intensities of the peaks with addition of silica, but the opposite was the case at higher contents. Actually, crystallinity index values of cellulose were increased with the addition of nano silica when using both the Segal and deconvolution methods, except for 1 g silica content on the latter method. However, crystallinity index generally decreased with increase in silica content. The observation suggest that the interaction of silica and cellulose is attenuated at higher contents which, in this study, could be confirmed by amalgamation of silica around the fibre at higher contents as seen from SEM.

Of more interesting is HCl catalyzed nano silica nanocomposites exhibited higher crystallinity index as compared to the ammonium catalysed nanocomposites. Das et al.15 related the observation to the base catalyst capability to produce small spherical SCN as compared to acid catalyst which normally yield high agglomeration for lower crystallinity index as compared to acid catalyst.

Thermogravimetric analysis(TGA)

Figures 4a and b present the TGA spectra of RSB, extracted cellulose, extracted nano-silica, and SCN composites (0.6 g, 0.8 g, and 1.0 g) treated with basic and acidic catalysts, respectively. The corresponding derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves for these samples under basic and acidic conditions are shown in Figs. 5a and b, respectively. Nano silica showed exceptional thermal stability compared to the rest with almost no degradation step except for volatilization of moisture around 100 °C. Meanwhile the fibres and composites exhibited three steps degradations as confirmed by DTG. The first degradation stage observed under 100 °C was attributed to loss of water content, the second degradation stage around 333 °C was associated with degradation of hemicellulose and the third degradation at 491 °C was attributed to lignin degradation13,15. The cellulose exhibited one main thermal degradation at 330 °C due to cellulose decomposition at high temperatures. In addition, approximately 2.1% cellulose weight loss was observed at 25–150 °C which was attributed to removal of water moisture15. The SCN (0.6 g, 0.8 g and 1 g SCN) exhibited one main thermal degradation peak, similarly to cellulose. From (a) and (b), the 0.6 g SCN showed the main thermal degradation between 290 and 380°C, whilst the 0.8 g and 1 g SCN exhibited the degradation at 284–370 °C and 270–37°C, respectively. The addition of extracted nano silica increased the thermal stability of cellulose and seemed to have reached a climax at 0.8 g at approximately 351°C trailed by 0.6 at approximately 334 °C. The similar pattern projected by crystallinity index values in XRD seems to resurface as the thermal stability declined at higher contents of silica.

Although the SEM results suggest the presence of a protective layer around the fibres at higher silica concentrations which would typically enhance thermal stability, the observed weak interactions, as indicated by the reduced crystallinity, likely explain the thermal behaviour in this study. Overall, composites catalysed by HCl demonstrated greater thermal stability compared to those catalysed by ammonium. This finding aligns with the XRD analysis, where HCl-catalysed nano-silica nanocomposites exhibited higher crystallinity index values.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to investigate and compare the morphology, crystallinity, and thermal properties of cellulose/silica nanocomposites prepared by the sol–gel technique under the influence of acid and base catalysts at varying concentrations of extracted nano silica. The SEM images revealed the interaction between the extracted nano silica and cellulose, indicating that the silica nanoparticles were wrapped around the surface of the cellulose fibres rather than observed directly on them. This was further evidenced by the average diameter measurements, which showed no significant change in the thickness of cellulose fibres at lower silica content, but an increase in diameter with higher silica content. The cellulose/silica nanocomposites prepared with hydrochloric acid had thicker diameters compared to those prepared with the base catalyst, both at low and high silica deposition levels. The crystallinity analysis demonstrated that the nanocomposites under hydrochloric acid exhibited higher crystallinity at 0.6 g and 0.8 g of silica content compared to those prepared with the ammonia catalyst. The base catalyst produced smaller spherical nanocomposites, leading to higher agglomeration and a lower crystallinity index compared to the acid catalyst. However, at higher nano silica levels, the crystallinity of the nanocomposites under hydrochloric acid decreased significantly compared to those under ammonia. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) revealed that the nanocomposites with 0.6 g and 0.8 g of silica catalysed by ammonia were the most thermally stable, whereas the nanocomposites with 0.8 g and 1 g of silica catalysed by hydrochloric acid showed the highest thermal stability. This study underscores the importance of catalyst type and silica concentration in determining the structural and thermal properties of cellulose/silica nanocomposites, offering valuable insights for their optimization in various applications. These cellulose nanosilica nanocomposites can be applied in water treatment for pollutant adsorption, biodegradable packaging for improved strength and sustainability, and biomedical fields such as wound dressings. Additionally, they enhance mechanical and thermal properties in construction materials, supporting environmentally friendly innovations across multiple real-world industrial sectors.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript at motaungte@live.com.

References

Jafari, V. & Allahverdi, A. Synthesis of nanosilica from silica fume using an acid-base precipitation technique and PVA as a nonionic surfactant. J. Ultrafine Grained Nanostruct. Mater. 47(2), 105–112 (2014).

Hoang, C. V. et al. Large-scale synthesis of nanosilica from silica sand for plant stimulant applications. ACS Omega 7(45), 41687–41695. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c05760 (2022).

Dlomo, K., Mohomane, S. M. & Motaung, T. E. Influence of silica nanoparticles on the properties of cellulose composite membranes: A current review. Cellul. Chem. Technol 54, 765–775 (2020).

Shange, M. G. et al. Factors affecting silica/cellulose nanocomposite prepared via the sol-gel technique: A review. Materials 17(9), 1937 (2024).

Sequeira, S., Evtuguin, D. V. & Portugal, I. Preparation and properties of cellulose/silica hybrid composites. Polym. Compos. 30(9), 1275–1282 (2009).

Ye, G., Synthesis and Characterization of Cellulose fiber-silica nanocomposites. (2014).

Salama, A. et al. Cellulose–silver composites materials: preparation and applications. Biomolecules 11(11), 1684 (2021).

Tsvetkova, I. et al. Sol-gel synthesis and investigation of hybrid organic-inorganic borosilicate nanocomposites. Glass Phys. Chem 32, 218–227 (2006).

Singh, L. P. et al. Sol-Gel processing of silica nanoparticles and their applications. Adv. Coll. Interface. Sci. 214, 17–37 (2014).

Xie, K., Yu, Y. & Shi, Y. Synthesis and characterization of cellulose/silica hybrid materials with chemical crosslinking. Carbohyd. Polym. 78(4), 799–805 (2009).

Ghamarpoor, R. & Jamshidi, M. Synthesis of vinyl-based silica nanoparticles by sol–gel method and their influences on network microstructure and dynamic mechanical properties of nitrile rubber nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 15286 (2022).

Esposito, S. “Traditional” sol-gel chemistry as a powerful tool for the preparation of supported metal and metal oxide catalysts. Materials 12(4), 668 (2019).

Soemphol, W. et al. Characterization of a bacterial cellulose-silica nanocomposite prepared from agricultural waste products. Mater. Res. Express 7(1), 015085 (2020).

Ashori, A. et al. Bacterial cellulose/silica nanocomposites: Preparation and characterization. Carbohyd. Polym. 90(1), 413–418 (2012).

Mohamed, R. et al. Synthesis of highly ordered cubic zeolite A and its ion-exchange behavior. Colloids Surf., A 348(1–3), 87–92 (2009).

Lei, B., Chen, X. & Koh, Y.-H. Effects of acidic catalysts on the microstructure and biological property of sol–gel bioactive glass microspheres. J. Sol-Gel. Sci. Technol. 58, 656–663 (2011).

Kuraoka, K. & Iwasaki, T. Preparation and gas barrier properties of cellulose nanocrystal-silica organic–inorganic hybrid gas barrier membranes with crosslinked structures. J. Sol-Gel. Sci. Technol. 104(3), 464–469 (2022).

Machado, A. A. & Mulky, L. A comparative study of treatment methods of raw sugarcane bagasse for adsorption of oil and diesel. Water Air Soil Pollut. 234(4), 213 (2023).

Ghaleb, A. A. S. et al. Sugarcane bagasse as a co-substrate with oil-refinery biological sludge for biogas production using batch mesophilic anaerobic co-digestion technology: Effect of carbon/nitrogen ratio. Water 13(5), 590 (2021).

Wulandari, W., A. Rochliadi & I. Arcana. Nanocellulose prepared by acid hydrolysis of isolated cellulose from sugarcane bagasse. in IOP conference series: materials science and engineering (IOP Publishing, 2016).

Teo, S. H. et al. Surface functionalization of sugarcane-bagasse-derived cellulose nanocrystal for pickering emulsion gel: Microstructural properties and stability efficiency. Gels 9(9), 734 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Thermo-responsive cellulose-based material with switchable wettability for controllable oil/water separation. Polymers 10(6), 592 (2018).

Ramlee, N. A. et al. Modification of oil palm empty fruit bunch and sugarcane bagasse biomass as potential reinforcement for composites panel and thermal insulation materials. J. Bionic Eng. 16, 175–188 (2019).

Thahir, R. et al. Synthesis of mesoporous silica SBA-15 through surfactant set-up and hydrothermal process. 12(3), 1117–1126 (2019).

Fu, J. et al. Facilitated fabrication of high strength silica aerogels using cellulose nanofibrils as scaffold. Carbohyd. Polym. 147, 89–96 (2016).

Li, M. et al. Physicochemical properties of nanocellulose isolated from cotton stalk waste. ACS Omega 6(39), 25162–25169 (2021).

Rodríguez-Robledo, M. C. et al. Cellulose-silica nanocomposites of high reinforcing content with fungi decay resistance by one-pot synthesis. Materials 11(4), 575 (2018).

Jia Ning, J. N. et al. Synthesis and characterization of cellulose-silica composite fiber in ethanol/water mixed solvents. BioResources 2, 1186–1195 (2011).

Motaung, T. E. & Mokhothu, T. H. The influence of supermasscolloider on the morphology of sugarcane bagasse and bagasse cellulose. Fibers Polym. 17, 343–350 (2016).

Shabangu, T., Linganiso, L. Z., Motaung, T. E., Setumo, M. V. & Koao, L. F. Comparison of fibre from maize stalk domains and sugar cane bagasse. Wood Res. 64, 601 (2019).

Yang, F. & Nelson, G. L. PMMA/silica nanocomposite studies: Synthesis and properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 91, 3844 (2004).

Muhammad, A. Z., Muhammad, A. W. & Hilal, N. Flux and rejection analysis of nanofiltration membranes for the treatment of surface water. Desalination 192(1–3), 262–271 (2006).

Hu, Y., Chen, C. Y. & Wang, C. C. Thermal degradation and kinetic analysis of biodegradable PBS-based copolyesters. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 84(3), 545–553 (2004).

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.E., Supervised and conceptualization of the manuscript, S.M., Supervised and conceptualization of the manuscript and M.G. wrote and collected data for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shange, M.G., Mohomane, S.M. & Motaung, T.E. Effect of synthesized silica on the properties of sugarcane bagasse cellulose/silica nanocomposites via sol–gel processing. Sci Rep 15, 26198 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10950-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10950-x