Abstract

The eastern part of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is located in the high-altitude freeze-thaw region, where terrestrial clastic red beds formed by sedimentation since the Mesozoic are widely distributed. Recently, red-bed coarse-grained materials (CGMs) have been increasingly utilised in construction in projects across western China. However, owing to the high degree of weathering and low strength, red-bed CGMs are susceptible to particle breakage under impact loads during compaction. This process results in an increased fine particle content (FC), which exacerbates frost heave during the service period, significantly compromising engineering stability. This study investigates the particle breakage and frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs, focusing on the effects of water content (w), initial fine particle content (FC0), and the number of freeze-thaw cycles (NFT). Based on experimental data, a frost heave ratio prediction model incorporating particle breakage effects was developed. This model accounts for the influence of w, FC0, and NFT on the frost heave ratio of red-bed CGMs, offering a scientific foundation for evaluating the suitability of these materials as engineering fillers in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Red beds are a type of clastic sedimentary rock with a characteristic red appearance, primarily formed under hot and arid paleoclimatic conditions during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras1,2,3,4,5,6. In China, red beds are predominantly found as red continental clastic deposits, with significant sedimentary periods occurring during the Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Tertiary. These sedimentary rocks are typically soft, highly weathered, and exhibit low strength7,8,9,10.

The eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, a high-altitude freeze-thaw region, is one of the main areas in China where red beds are concentrated. With the rapid development of infrastructure in western China, increasing numbers of engineering projects are being constructed in these red-bed sedimentary zones, using red-bed coarse-grained materials (CGMs) as filling materials. These CGMs, characterised by high weathering and low strength, undergo significant particle breakage during the compaction process11,12. Additionally, the mineral composition of red beds often includes a high proportion of clay-expansive components, and their internal structure is formed by weakly cemented composite minerals. In high-altitude freeze-thaw regions, these characteristics render red-bed CGMs particularly susceptible to frost heave owing to large temperature fluctuations and repeated freeze-thaw cycles13,14. The particles breakage significantly increases the proportion of fine particles that are sensitive to frost heave within CGMs15, thereby exacerbating frost heave phenomenon and severely compromising the stability of engineering projects.

Current research on red-bed CGMs primarily focuses on their strength and deformation behaviour under dynamic and static loads. Numerous direct shear and compression tests have been conducted to evaluate their physical and mechanical properties under various conditions16,17. Additionally, the creep characteristics under water-rock interactions have garnered significant attention, leading to the development of theoretical systems for soft rock creep. These frameworks include composite component, empirical, and constitutive models18,19,20,21,22,23.

When red-bed CGMs are used as filling materials, particle breakage frequently occurs during compaction, resulting in changes in grain size gradation and compactness15. The particle breakage characteristics of soils are influenced by their mineral composition and material properties24. A higher initial particle breakage degree typically correlates with worse subsequent breakage, and the deterioration of coarse particle lithology significantly amplifies this effect25. Given the high degree of weathering and low strength of red-bed CGMs, external forces such as compaction play a critical role in their breakage. Existing studies on red-bed CGM breakage primarily focus on natural disintegration under varying environmental conditions. However, limited attention has been given to breakage properties during compaction or the effects of factors such as initial gradation and water content (w) on particle breakage26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33.

Additionally, research indicates that fine particles (FC) in CGMs are highly sensitive to frost heave, with a strong tendency to adsorb onto each other to form clusters—a critical factor affecting the frost heave ratio34,35,36,37. Compared to fine-grained components (with a particle size less than 0.075 mm), coarse-grained components (gravel and sand) have more pores and better connectivity, resulting in higher permeability. The water is less likely to accumulate within the soil, leading to a relatively smaller number of ice crystals formed during freezing and a lower frost heave. This effectively suppresses the frost heave of the fillers, making the fine-grained content in the fillers an important indicator of concern for researchers studying subgrade engineering in cold regions. The particle breakage of red-bed CGMs during compaction leads to a noticeable increase in FC, which exacerbates frost heave in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions. Despite this, there is limited research on the frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs, and predictive models that consider various influencing factors are lacking. The annual increase in engineering applications using red-bed CGMs as filling materials in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions underscores the urgency of addressing this knowledge gap. The scarcity of research on the particle breakage and frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs has significantly hindered their development and application as engineering filling materials in such challenging environments.

In response to the engineering requirement for the applicability of red-bed CGMs in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions, and based on the current limitations in understanding the particle breakage and frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs, this study conducted a series of compaction and freeze-thaw (F-T) tests to investigate the particle breakage and frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs, considering the effects of water content (w), initial fine particle content (FC0), and the number of freeze-thaw cycles (NFT). The correlation between particle breakage and frost heave ratio of red-bed CGMs was analysed, and a frost heave prediction model was established using multiple regression analysis. This model enables accurate prediction of the frost heave ratio under varying conditions of water content (w), initial fine particle contents (FC0), and numbers of freeze-thaw cycles (NFT), providing a scientific foundation for analysing the suitability of red-bed CGMs as engineering fillers in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions.

Materials and methodology

Material properties

The red-bed CGMs used in this study were the filling materials from an actual red-bed soft rock engineering project in Qamdo City, China, located in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions. The geological and meteorological conditions of the sampling locations are shown in Fig. 1(a-d)6,38,39. The gradation curves are illustrated in shown Fig. 2. The effect of the FC0, defined as particles smaller than 0.075 mm, ranging from 0 to 15%, was considered in this study. The maximum dry density of the red-bed CGMs is 2.25 kg/cm³, and the optimal water content is 7.8%.

Geological environment survey of sampling point of red-bed filling engineering in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions: (a) distribution of red beds worldwide. Modified from38, Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. (b) distribution of red beds and frozen soil in China. Modified from39, Copyright 2012, John Wiley and Sons. (c) field sampling area (Qamdo City), (d) monthly average temperature monitoring data of the sampling area.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results for the red-bed CGMs are presented in Fig. 3. The XRD and SEM analyses revealed a high clay mineral content in the red-bed CGMs, aligning with findings from previous studies40,41,42,43. The swelling minerals, including montmorillonite and illite, accounted for more than 40% of the total composition. The structure of the red-bed CGMs was relatively dense, with a uniform pore distribution, and exhibited a typical irregular thin-layer clay mineral structure. The particle morphology was predominantly curled and flaky, further indicating a significant presence of clay minerals such as illite. The unique mineral composition and microstructure of the red-bed CGMs make it highly sensitive to breakage and frost heave.

Particle breakage test

To explore the breakage and frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs, as well as the correlation between the two, this study first conducted particle breakage tests on red-bed CGMs. Figure 4 shows the particle breakage test process. The tests were conducted using a Z2 heavy compactor, an automatic impact apparatus. The compactor employed a hammer weighing 4.5 kg with a drop height of 45.7 cm. The effects of FC0 and w were also investigated (Table 1). The impact work is applied to the filler by the falling hammer, causing the filler to break. The compaction energies is applied to red-bed CGMs by the falling hammer, causing the materials to break. The samples were divided into three layers for compaction, with the mass of each layer calculated based on 95% of the maximum dry density. The mass of particles from each size range in each layer was determined using the grain size distribution curve (Fig. 2). Particles from each size range were weighed separately and thoroughly mixed for each layer to ensure consistent particle mass distribution across all layers. Purified water was then added to the weighed red-bed CGMs, and the uniformly mixed soil samples were stored in sealed bags for 24 h to prevent evaporation and ensure uniform moisture distribution.

The prepared samples were layered into a container, with each layer compacted 56 times. Under the impact load, the red-bed CGMs exhibited significant particle breakage. After compaction, the samples were removed and dried at 105 °C for 24 h. Once cooled to 20 °C, the red-bed CGMs were re-screened, and the gradation curve reflecting compaction-induced particle breakage was obtained. Based on the obtained gradation curve, the particle breakage index Br proposed by Hardin was cited to describe the particle breakage phenomenon of the red-bed CGMs25, thereby characterizing the severity of particle breakage. The calculation formula of Br is shown in Fig. 5, where Bt represents the particle breakage amount, and Bp denotes the breakage potential.

Unidirectional freeze-thaw test

The unidirectional freeze-thaw (F-T) test setup, which includes an ambient temperature control box, a cold bath, and a data acquisition system, is illustrated in Fig. 6. The F-T chamber utilises air cooling with a temperature control range of −35 °C to + 40 °C. A closed-loop control system based on a neural network-PID algorithm was employed for precise temperature regulation. The top and bottom temperatures of the sample were independently controlled by two industrial alcohol-filled cold baths, with a temperature accuracy of ± 0.1 °C. The bottom is maintained at a constant positive temperature (warm end), and the top is the cooling end and the heating end (cold end). The sample chamber was constructed from plexiglass, with an inner diameter of 102 mm, a height of 245 mm, and a wall thickness of 10 mm. A 3 mm diameter hole was reserved in the sidewall for the placement of a temperature sensor. The data acquisition system included a temperature sensor, a displacement sensor, and a data collector.

This study considered the effects of w, FC0, and NFT. The F-T cycle test schemes are listed in Table 2. The preparation of the samples strictly adhered to the Code for the Soil Test of Railway Engineering44. The required quantity of red-bed CGMs for each test was weighed according to the grain-size distribution, mixed with water, and sealed in a bag for 24 h to ensure uniform moisture distribution. Cylindrical samples with a height of 200 mm and a diameter of 100 mm were prepared using a layered method. The prepared samples were transferred to acrylic tubes and placed on the equipment base. Five temperature sensors were inserted horizontally at different heights, and their positions were recorded. The cold end of the sample was positioned at the top and kept horizontal. A displacement sensor was installed at the top of the sample to ensure it operated effectively within its range. Insulating material was wrapped around the acrylic tube to prevent heat loss.

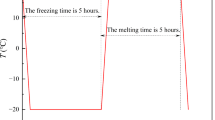

Five temperature sensors were placed at 30 mm intervals along the specimen height, while the displacement sensor at the top monitored frost heave during the F-T cycle process. The specimen was initially placed in the chamber at room temperature. Based on the temperature monitoring data from the sampling area, the cold end temperature was set to −15 °C during freezing phase, while during the thawing phase, it was set to + 5 °C. The warm end was maintained at + 5 °C. The ambient temperature was set to + 5 °C, corresponding to the constant-temperature soil layer at the construction site. Each cycle consisted of a 12-hour freezing phase at −15 °C, followed by a 12-hour thawing phase at + 5 °C.

Based on the groundwater level conditions in the fill sampling area, water supply replenishment was not considered. Previous studies have indicated that during the freezing process of coarse-grained subgrade filling materials, liquid water primarily accumulates in the intergranular pores, forming pore ice grains that are closely bonded with soil particles. In contrast, water vapor is more readily transported to the upper surface of the specimen, where it forms a thin ice layer that exacerbates frost heave45. Therefore, a closed-system approach was employed to conduct the unidirectional freeze-thaw test in this study.

In order to further explore the influence of NFT on red-bed CGMs at a mesoscopic level, the samples under different freeze-thaw cycles were scanned and reconstructed using a CT scanning imaging device. After image processing and binarization segmentation, the internal pore structure of the sample was extracted, and the pore evolution characteristics of red-bed CGMs under the action of freeze-thaw cycles were obtained. In addition, by removing isolated pores, the variation of connected porosity can be obtained (connected porosity refers to the ratio of the pore volume after removing isolated pores to the total volume of the sample). The results of CT scan tests can explain and supplement the analysis of macroscopic frost heaving phenomena from a mesoscopic perspective, and are more conducive to understanding the freeze-thaw damage mechanism of red-bed CGMs.

Test results and discussion

Changes in particle breakage characteristics under impact load

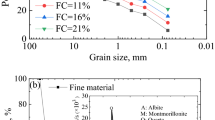

Effect of initial fine particle content. The cumulative gradation curves of red-bed CGMs, both before and after compaction under an impact load at w = 8%, are presented in Fig. 7. These results indicate that the FC0 significantly impacts particle breakage. The particle breakage decreased as FC0 increased. As FC0 increased from 0 to 15%, the relative particle breakage rate Br decreased from 0.86 to 0.52.

The changes in particle size before and after compaction for various FC0 levels are depicted in Fig. 8(a), providing a more detailed view of the particle breakage effect. The results indicate that particles smaller than 1 mm increased in mass after compaction, with the most significant growth observed in particles smaller than 0.25 mm. Conversely, particles in the 10–20 mm range exhibited the largest reduction in mass during compaction across all groups. Particles within the 0.25–2 mm range experienced minimal fluctuation, indicating that FC0 had little impact on this size range. As FC0 increased, the breakage degree of larger particles, particularly those in the 2–20 mm range, reduced significantly.

Effect of water content. The changes in particle size after compaction under different water contents (w) are illustrated in Fig. 8(b). When FC0 remained constant and w was below the optimal water content, an increase in w brought the sample closer to the optimal level, reducing particle breakage. However, when w exceeded the optimal level, red-bed CGMs softened easily upon water contact. Excessive water content also increased the softening rate during compaction, significantly amplifying the breakage effect.

Effect of CGMs type. The breakage characteristics of several types of CGMs, including conventional breccia soil CGMs15, carbonaceous mudstone CGMs46, and coal gangue CGMs47, are presented in Fig. 9. The results indicate that red-bed CGMs experience the highest degree of breakage, while conventional breccia soil CGMs exhibit the lowest degree, with breakage limited to coarse particles in the 10–20 mm range. Carbonaceous mudstone and coal gangue CGMs demonstrate similar breakage behaviours, though larger particles in the carbonaceous mudstone CGMs were more susceptible to breakage.

From the perspective of mineral and structural composition, the clay mineral components such as montmorillonite and illite in the red-bed CGMs of this study account for more than 40% of the total composition (Fig. 3). Additionally, the internal structure of the red bed soft rock is weakly cemented, resulting in the highest degree of breakage under impact loading compared to other fillers. Conventional breccia soil CGMs is typically used as filler for high-speed railway subgrades and has relatively high strength, leading to a lower degree of breakage. The lithology of carbonaceous mudstone lies between mudstone and coal, and it also contains a certain proportion of clay minerals, resulting in a higher degree of breakage than conventional breccia soil CGMs. Coal gangue CGMs, a type of solid waste from mining, has a certain degree of weathering, and based on the breakage results, its degree of breakage falls between that of carbonaceous mudstone CGMs and breccia soil CGMs.

Frost heave charateristics under F-T cycles

Effect of initial fine particle content. The typical trends of temperature and frost heave deformation during F-T cycles for red-bed CGMs are illustrated in Fig. 10. During the initial freezing phase, a pronounced temperature gradient was observed at the cold end, coupled with a rapid cooling rate. As cooling progressed, the internal temperature of the sample stabilised. Similarly, during the early thawing phase, the warming rate matched the cooling rate observed at the beginning of freezing, after which the internal temperature stabilised again. The high content of clay-type expansive minerals in red-bed CGMs caused noticeable frost heave, driven by volume changes associated with the ice–water phase transition during freezing. The displacement–time curve at the top of the sample demonstrated significant frost heave during the freezing phase. The stability of the data confirms the reliability of the test results and the efficient heat transfer capabilities of the testing instrument.

The frost heave behavior of red-bed CGMs with different initial fine particle contents (FC0) is depicted in Fig. 11(a). The findings show that as FC0 increased from 0 to 15%, both frost heave deformation and the frost heave ratio rose significantly. The frost heave ratio is defined as the ratio of the maximum frost heave to the freezing depth. Engineering experience in cold regions has consistently shown that fine particles contribute to the frost heave of CGMs, a conclusion supported by a prior study conducted by our team45,48. Compared to ordinary CGMs studied previously, red-bed CGMs exhibited a stronger frost heave effect. This is attributed primarily to the high content of clay-type expansive minerals in red-bed CGMs, which undergo significant volume expansion and frost heave under low-temperature conditions, as evidenced by the XRD and SEM analyses (Fig. 3). In contrast, particle breakage test results revealed that the degree of breakage in red-bed CGMs during compaction was substantially higher than in other typical CGMs. As a result of compaction, the fine particle content (FC) of the sample increased from its initial value (FC0) to FC0 + ΔFC, where ΔFC represents the additional fine particles generated during compaction. The combined effects of mineral composition and particle breakage on fine particle content significantly contributed to the pronounced frost heave deformation observed in red-bed CGMs.

Effect of water content. The frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs, influenced by varying water contents (w) and initial fine particle contents (FC0), are illustrated in Fig. 11(b) and (c). The results demonstrate that water content significantly influences the frost heave behaviour of red-bed CGMs. In high-altitude freeze-thaw regions, water and low temperatures act as critical external factors, while the phase transition between ice and water remains the fundamental mechanism driving frost heave. Additionally, during the service period of engineering filling materials, the water content often exceeds its initial state, exacerbating frost heave effects. Notably, even when FC0 is relatively low (e.g., 4%), the frost heave ratio exceeds 1% at w = 12%, which categorises the material as frost-heave-sensitive soil according to cold-region engineering criteria49. These results highlight the need for stricter control of FC0 and water content in red-bed CGMs used in cold regions. Unlike ordinary filling materials, where the fine particle content limit is generally 15%, the recommended FC0 limit for red-bed CGMs in cold regions should be reduced to approximately 5%, considering local groundwater conditions.

Effect of freeze-thaw cycles. The frost heave deformation and microporosity of red-bed CGMs during five F-T cycles at FC0 = 8% with different water contents are illustrated in Fig. 12. The displacement changes at the top of the samples showed consistent trends under various conditions. Notably, samples with higher water content exhibited greater frost heave effects due to the F-T cycles. After three F-T cycles, the maximum frost heave for the samples stabilised, indicating that the internal damage caused by the F-T cycles had reached equilibrium. Consequently, the final frost heave and thaw settlement values also tended to stabilise, a result consistent with our previous findings50.

To further explore the impact of NFT on red-bed CGMs at a microscopic level, the sample was scanned and reconstructed using a microscopic testing and imaging device. Figure 12(b) shows the changes in internal porosity of the sample under different freeze-thaw cycles. It can be observed that as the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases, the pores inside the red-bed CGMs gradually expand, and the connectivity of the pores enhances, indicating structural damage. Quantitative analysis of porosity revealed that the changes in pore structure stabilised after three F-T cycles, and the porosity values also stabilised. This trend aligns with the macro-frost heave observations, indicating that the impact of NFT on red-bed CGMs occurs primarily between three and five cycles.

Frost heave ratio prediction model

FC increment expression

The fine particles in red-bed CGMs, containing a higher proportion of clay minerals, contribute significantly to frost heave deformation under F-T cycles. Particle breakage during the compaction process of red-bed CGMs leads to a considerable increase in the content of fine particles that are sensitive to frost heave, exacerbating the frost heave phenomenon. However, research on the correlation between particle breakage and frost heave in red-bed CGMs is limited.

This study established the relationship between the increase in fine particles caused by compaction and initial fine particle content (FC0) and water content (w) through compaction experiments. By converting compaction energy, the fine particle content in the red-bed CGMs before the frost heave test was determined, which is the sum of the initial fine particle content and the fine particle increment. A frost heave prediction model for red-bed CGMs was then developed through regression analysis of the frost heave test data, considering the fine particle increments, water content, and F-T cycles.

The compaction effect under impact load causes the fine particle content in the red-bed CGMs to change from FC0 to FC0 + ΔFC. This study primarily focused on analysing the effects of different initial fine particle contents (FC0) and water contents (w) on the compaction breakage of red-bed CGMs. The fitting relationship between ΔFC, caused by the impact load during the compaction process, and FC0 and w is shown in Fig. 13, as represented by Eqs. (1) and (2). The linear first-order function fits well with the relationship between ΔFC and FC0, while the polynomial second-order function can effectively describe the evolution of ΔFC with respect to w0. The R² values are greater than 0.96, indicating that the fitting functions can accurately reflect the evolution of ΔFC. Considering the influence of FC0 and w0, the empirical relation function of ΔFC is established through multiple regression analysis method50, as shown in Eqs. (3) and (4).

where \(\lambda\) is the multiple regression coefficients of the model, \(f(F{C_0})\) is a function of initial fine content, and \(g({w_0})\) is a function of water content. The fitting parameters, A1, A2, B1, B2 and B3, are detailed in Table 3. FC0 is the initial fine particle content, while w0 is the water content.

Frost heave ratio prediction

Before the frost heave test, the samples underwent initial particle breakage during compaction, leading to an increase in the fine content of the red-bed CGMs. However, while a heavy-duty compactor was employed for the above compaction test, a light-duty compactor was used during the preparation of samples for the frost heave test. Consequently, the compaction energy applied differed under identical initial conditions. Previous studies have shown that compaction energy is the main cause of particle breakage, and there are nonlinear characteristics between the breakage indicators such as fine particle increment and the compaction energy24,25,51,52. The research is oriented towards practical engineering and simplifies the treatment of this issue. A linear proportional sequence relationship was used to convert the compaction energy and the increment of fine particles, as shown in Eq. (5). The fine particle increment per unit compaction energy (\({{\Delta FC} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\Delta FC} {{W_1}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{W_1}}}\)) was obtained through the breakage test using a heavy-duty compacting instrument. Then, based on the compaction energy (\({W_2}\)) of a light-duty compacting instrument, the fine particle increment (\(\varDelta\:F{C}^{{\prime\:}}\)) represents the fine particle increment caused by specimen preparation using a light-duty compacting instrument before the frost heave test. W1 and W2 denote the compaction energies of the heavy and light compaction instruments (W is calculated based on the weight of the hammer, the drop height, and the number of blows of the impact tester. The different instrument parameters of heavy and light compaction instruments result in different values for W1 and W2), respectively, with their values listed in Table 3.

Using this transformation, the actual fine particle content (\(F{C}_{0}+\varDelta\:F{C}^{{\prime\:}}\)) of the samples prior to the frost heave test was determined. Based on the frost heave test results of the red-bed CGMs, multiple regression analysis was employed to establish empirical relationship functions between the fine particle content, water content, number of freeze-thaw cycles (F-T cycles), and frost heave ratio, as represented in Eqs. (6)−(8). As shown in Fig. 14, the frost heave ratio exhibits a linear relationship with the fine particle content. Additionally, the relationship between the frost heave ratio and water content, as well as the frost heave ratio and the number of F-T cycles, can be effectively described using exponential functions. The correlation coefficients of these functions exceed 0.97, confirming their accuracy. Considering these three influencing factors, a frost heave prediction model for red-bed CGMs that incorporates particle breakage characteristics was developed through multiple regression analysis, as shown in Eqs. (9) and (10).

Where µ represents the model parameter, \(h\left(F{C}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\) is a function of fine content, \(m(w)\) is a function of water content, and \(n(N)\) is a function of the number of F-T cycles. \(F{C_0}\) denotes the initial fine particle content, \(\varDelta\:F{C}^{{\prime\:}}\) indicates the increase in fine particles due to sample preparation for the frost heave test, w refers to the water content, N represents the number of freeze-thaw cycles, and C1, C2, D1, D2, D3, E1, E2, and E3 signify the fitting parameters. The specific values of these parameters are listed in Table 3.

The applicability of the proposed frost heave prediction model is notably limited to approximately five F-T cycles. While the performance of red-bed CGMs appeared to stabilise after 3–5 F-T cycles, exceeding 10 cycles is not recommended. The fitting formula derived in this study is empirical, and future research should investigate additional F-T cycles and conduct further experiments for enhanced validation.

Model evaluation

The relationship between the initial fine particle content (FC0), water content (w), number of freeze-thaw cycles (NFT), and the maximum frost heave ratio is defined by Eq. (10). To validate the reliability of this model, measured data from specimens not included in the empirical development of the model were used for comparison. The results are presented in Figs. 15 and 16. Figure 15 depicts comparision of the predicted and experimental data of ΔFC. Figure 16 shows comparision of the predicted and experimental data of η. The findings demonstrate that the empirical model proposed in this study effectively predicts the frost heave ratio of red-bed CGMs under varying conditions of fine particle content, water content, and F-T cycles. The accuracy of the multiple regression analysis exceeded 98%, indicating high precision. This model offers a practical approach to quantifying the combined effects of fine particle content, water content, and NFT cycles on the maximum frost heave ratio of red-bed CGMs. Additionally, the model incorporates the influence of particle breakage characteristics during the compaction process, which is crucial for understanding frost heave behaviour. This feature is especially valuable for the construction and operation of engineering projects utilising red-bed CGMs as filling materials in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions.

Discussions

In recent years, the red-bed CGMs have gradually been utilized as engineering filling materials in the high-altitude freeze-thaw regions of China. However, these materials are characterized by a unique mineral composition and physico-mechanical properties, which lead to significant particle breakage during the filling process. Moreover, their frost heave characteristics during the operational period remain poorly understood. This study aims to explore the breakage and frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs and the relationship between these two properties. It is of great significance for disaster prevention and control of engineerings filled with red-bed CGMs in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions. Based on the above experimental and theoretical analysis results, the following discussions are made on the relevant experimental results of this study.

The initiation mechanism of particle breakage of red-bed CGMs

This study focuses on the red-bed CGMs in the high-altitude freeze-thaw regions of eastern part of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in China. The study area is characterized by the presence of terrestrial clastic red beds that have been formed since the Mesozoic era. These red-bed soft rocks are predominantly cemented by clay or calcium, exhibiting low cementation strength and high weathering intensity. In actual filling projects, dynamic impact forces generated by vibratory compaction far exceed the particle strength of the red-bed CGMs, leading to severe breakage during the construction phase15.

This study investigated the effects of initial fine content (FC0) and water content (w), two important indicators in roadbed engineering, on the particle breakage of red-bed CGMs. The results shown in Figs. 7 and 8 indicate that the initial fine-grain content and water content significantly affect particle breakage. As the FC0 increases, the particle breakage rate decreases. From the perspective of the spatial structure of the samples, this trend occurs because samples with lower FC0 levels contain a higher proportion of coarse particles, forming a skeleton-void structure. This further leads to stress concentration between particles. In the absence of buffering between particles under impact loads, this stress concentration exacerbates the particle breakage of red-bed CGMs.

Moreover, it was found that the effect of water content on particle breakage seems to have an extremum (near the optimum water content). This phenomenon occurs because water fills the voids between particles and effectively lubricates and cushions them during relative motion, thereby minimizing particle breakage to the greatest extent. When the water content exceeds the optimum level, the cementitious materials within the red-bed CGMs are susceptible to dissolution upon contact with water (commonly referred to as softening in engineering). Excessive water content also increases the softening rate during compaction, significantly amplifying the breakage effect. Therefore, maintaining the optimum water content in the actual engineering compaction process to minimize particle breakage in red-bed CGMs is crucial. Figure 9 further confirms that the degree of particle breakage in red-bed CGMs far exceeds that of other types of filling materials. This indicates that in actual red-bed CGMs filling engineerings, particle breakage cannot be ignored, and it is necessary to focus on the changes in the performance of the engineering filling materials brought about by this phenomenon.

The Frost heave mechanism of red-bed CGMs

The study area is located in the high-altitude freeze-thaw regions of China, where red-bed CGMs are subjected to frequent freeze-thaw cycles, and the frost heave of these materials cannot be ignored. The essence of frost heave is the result of the combined action of the volume expansion of water when it freezes (ice has a volume 9% greater than water) and the migration of water (unfrozen water moves towards the freezing front). The occurrence of frost heave in soil requires the simultaneous fulfillment of several conditions: (1) the presence of fine-grained soil (particle size less than 0.075 mm) to provide capillary channels for water migration, (2) sufficient moisture, and (3) a sustained low-temperature environment, with the duration of negative temperature being greater than the time required for the freezing front to advance53.

The results of XRD and SEM analyses on red-bed CGMs indicate that swelling minerals such as montmorillonite and illite constitute over 40% of their total composition. These minerals form a uniform pore distribution, characterized by an irregular thin-layered clay structure. The clay minerals exhibit strong water absorption and significant water retention capabilities. When these minerals absorb water and expand, they increase porosity and enhance capillary action. Additionally, the internal calcareous or clayey cementing materials are prone to softening when in contact with water, accelerating the release of fine particles (an increase in frost heave active particles). This unique mineral composition and microstructure make them highly susceptible to frost heave.

This study investigated the effects of different initial fine content (FC0) and water content (w), on the frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs. It can be seen that the influence of FC0 is significant, and the possible reason is that the aforementioned particle breakage effect leads to a significant increase in the FC0 (frost heave active particles) of red-bed CGMs during compaction, thereby exacerbating the frost heave of the filling materials during the operation period. The results under different water contents highlight the necessity for stricter control of w when using red-bed CGMs in cold regions. To ensure compaction effectiveness, the water content should be kept as close to the optimum water content as possible. In addition, if the groundwater conditions are abundant, it is necessary to consider adding anti-freeze materials to enhance the frost resistance of red-bed CGMs. For example, adding cement, lime, and other materials to solidify clay minerals can reduce frost heave sensitivity. Alternatively, adding sand and gravel to optimize gradation can disrupt the continuity of capillary channels54.

The change mechanism of mesostructure of red-bed CGMs under freeze-thaw cycles

To further investigate the effects of freeze-thaw cycles on red-bed CGMs at the mesostructural level, we also conducted CT scanning tests. As can be seen from Fig. 12, freeze-thaw cycles have a significant impact on the internal pore structure of red-bed CGMs, with both porosity and connected porosity increasing markedly. Figure 17(a) illustrates the mesostructural changes in red-bed CGMs subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. During the freezing period, the growth of ice crystals in the pores exerts frost heave forces on the particles, disrupting the internal cementation. This results in an increase in the number of pores and their connectivity. For red-bed CGMs, there are extremely high clay minerals in its fine particles, resulting in water retention capabilities and greater frost heave force in low-temperature environments. Moreover, the compaction effect increases the fine-grained components (frost heave active particles) of red-bed CGMs, thereby exacerbating the internal damage of the materials during the freeze-thaw process described in Fig. 17(a). Meanwhile, due to the high degree of weathering and low strength of red-bed CGMs, freeze-thaw cycles easily lead to the disintegration and breakage of large particles, thereby giving rise to fine microcracks. During the spring thaw, a large amount of meltwater infiltrates the expanded pore network, flushing away some fine soil particles and dissolving parts of the clay minerals, thus continuously enlarging the pore space. From May to September of the following year, the infiltration of rainwater during the rainy season into the expanded pore network further enlarges the pore channels.

To illustrate the particle disintegration and breakage effect caused by freeze-thaw cycles, based on the CT scanning tests, the watershed algorithm was adopted to extract the internal particle change characteristics of the specimens under freeze-thaw cycles, as shown in Fig. 17(b, c). Due to the requirements of the built-in particle reconstruction algorithm in the scanning equipment, the particle size division is different from the gradation in the macroscopic compaction and breakage test. It can be seen that the freeze-thaw cycle causes the large particles in the specimen to disintegrate and break into small particles, and the average particle size decreases with the increase of the number of freeze-thaw cycles. This indicates that for red-bed CGMs, the compaction process during the construction period is the main process that leads to changes in particle size. However, when the project enters the operation period, the disintegration of large particles will also cause a certain degree of change in particle composition. This phenomenon might need to be given a certain degree of attention in future related research.

Under the frequent freeze-thaw cycle conditions in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions, irreversible damage will occur within red-bed CGMs, thereby affecting their macroscopic properties. It is recommended that in practical engineering applications, when using red-bed CGMs as filling materials, the mechanical indices obtained from samples that have undergone approximately three to five freeze-thaw cycles should be regarded as design values. This approach ensures that the design accurately reflects the long-term behavior of red-bed CGMs under freeze-thaw conditions.

The correlation between particle breakage and Frost heave in red-bed CGMs

Based on the results and analyses of the experiments on particle breakage and frost heave of red-bed CGMs, it can be concluded that the particle breakage effect of red-bed CGMs leads to a significant increase in fine contents that are highly susceptible to frost heave. To characterize and quantify the impact of particle breakage in red-bed CGMs on frost heave characteristics, we established a frost heave prediction model for red-bed CGMs considering fine content, water content, and freeze-thaw cycles using multiple regression analysis. Given that heavy and light compaction instruments generate different compaction energies, we determined the fine-grain content state of the samples before frost heave through the conversion of compaction energies. This allowed us to incorporate the effect of the fine-grain increment caused by particle breakage into the frost heave prediction model and validated its reliability. The model can calculate the particle breakage and frost heave of red-bed CGMs under different initial conditions. This feature has certain theoretical and practical value for the construction and operation of engineering projects using red-bed CGMs as fillers in high-altitude freeze-thaw regions.

Conclusion

This study involved conducting laboratory compaction tests and frost heave tests on red-bed coarse-grained materials (CGMs) with varying initial fine content (FC0), water content (w), and number of freeze-thaw cycles (NFT). A frost heave prediction model for red-bed CGMs was developed and evaluated based on the collected data. The key findings are as follows:

-

(1)

Red-bed CGMs exhibit a higher degree of particle breakage during compaction compared to other typical CGMs. The potential for particle breakage decreases with increasing FC0. Both excessively high and low w exacerbate particle breakage, highlighting the importance of strict control over w during compaction to minimise its effects. Particles sized between 10 mm and 20 mm experienced the largest mass reduction during compaction, whereas particles smaller than 0.25 mm exhibited the largest increase.

-

(2)

The clay minerals in the red-bed CGMs, with a content of up to 40%, cause significant expansion of the fillers under F-T cycles, leading to severe frost heave phenomena. The accumulated frost heave deformation increases with the number of F-T cycles. After three cycles, the changes in pore structure and F-T deformation tend to stabilize, indicating that the values of frost heave and thaw settlement also stabilize. In practical engineering, repeated F-T cycles will lead to the deterioration of the structure, causing cracks and uplift in the subgrade, which affects driving safety and shortens the service life of the subgrade. To mitigate excessive frost heave, the fine particle content of the red-bed CGMs should not exceed 5%. It is also recommended that during construction, the w of the subgrade fillers be maintained close to the optimal content to ensure proper compaction. Additionally, capillary barriers or lateral drainage layers can be installed to control the w of the fillers and suppress frost heave.

-

(3)

A frost heave prediction model for red-bed CGMs was established using multiple regression analysis. The model accounts for particle breakage characteristics, enabling accurate predictions of the maximum frost heave ratio based on FC0, w, and NFT. The model achieved an accuracy exceeding 98%, confirming its reliability. By incorporating the particle breakage effect, the model is particularly valuable for construction projects in cold regions using red-bed CGMs as filling materials, providing both practical and theoretical significance. In the future, indoor tests can be expanded to include field compaction and in-situ frost heave tests, which will yield results that are more aligned with actual conditions and can better guide engineering construction.

The results were derived from laboratory impact load tests and F-T tests, focusing on the gradation, water content, and NFT of red-bed CGMs. Due to experimental conditions, the particle breakage tests in this study were conducted indoors using a heavy compaction apparatus, and field compaction tests for red-bed CGMs have not yet been performed. However, based on the analytical methods of this study, the actual breakage conditions in the field can still be inferred through the conversion of compaction energy. Currently, we are conducting engineering site compaction tests on red-bed CGMs, and we will publish the relevant results in the future. Furthermore, in order to simplify the calculation, in this study, a linear proportional relationship was adopted to calculate the fine particle increments under different compaction energies. In order to obtain a more accurate analytical relationship between compaction energy and fine particle increment, systematic experiments need to be conducted, such as considering the influence of different compaction energies and load types (static pressure, vibration, impact load, etc.) on the breakage degree and fine particle increment of the red-bed CGMs. We are currently carrying out this work and hope that it can also be presented in the form of a research report in the future. Regarding the freeze-thaw tests, most studies indicate that the significant effects of freeze-thaw cycles on soil occur within 10 cycles due to the thermal conductivity of the soil. Due to experimental limitations, this study did not conduct tests exceeding 5 F-T cycles, but the evolution of frost heave rates under multiple cycles can be obtained through data fitting. In the future, we will conduct freeze-thaw tests with more cycles to enhance the research results and provide more comprehensive insights for cold-region geotechnical engineering using red-bed CGMs for subgrade construction. Additionally, the freeze-thaw tests in this study did not consider the replenishment of water. Subsequent research will focus on the frost heave characteristics of red-bed CGMs under water replenishment conditions and explore the impact of groundwater accumulation on the frost heave characteristics of the fill material.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author (Shuang Tian) on reasonable request.

References

Vinnichenko, G. P. & Kukhtikov, M. M. New data on tertiary continental deposits of the Southwestern Pamir. Int. Geol. Rev. 21 (12), 1377–1382. https://doi.org/10.1080/00206818209467187 (1979).

Zaman, H. & Torill, M. Palaeomagnetic study of cretaceous red beds from the Eastern Hindukush ranges, Northern pakistan: palaeoreconstruction of Kohistan-Karakoram composite unit before the India-Asia collision. Geophys. J. Int. 136 (3), 719–738. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-246x.1999.00757.x (1999).

Kodama, K. & Takeda, T. Paleomagnetism of mid-Cretaceous red beds in west-central Kyushu island, Southwest Japan paleoposition of cretaceous sedimentary basins along the Eastern margin of Asia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 201 (1), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00691-X (2002).

Cheng, Q., Kou, X. B. & Huang, S. B. Distribution and geological environment characteristics of red beds in China. J. Eng. Geol. 12 (1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-9665.2004.01.007 (2004). (in Chinese).

Yamashita, I., Surinkum, A. & Wada, Y. Paleomagnetism of the middle late jurassic to cretaceous red beds from the Peninsular thailand: implications for collision tectonics. J. Asian Earth Sci. 40 (3), 784–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2010.11.001 (2011).

Pan, Z. X. & Peng, H. Comparative study of red layer distribution and geomorphic development at home and abroad. Scientia Geogr. Sinica. 35 (12), 1575–1584. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-6301.2003.02.001 (2015). (in Chinese).

Liu, Z., Hem, X. F., Fan, J. & Zhou, C. Y. Study on the softening mechanism and control of Redbed soft rock under seawater conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 7 (7), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse7070235 (2019).

Huang, K. et al. Mechanical behavior and fracture mechanism of red-bed mudstone under varied dry-wet cycling and prefabricated fracture planes with different loading angles. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 127, 104094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.104094 (2023).

Liu, X. C., Huang, F., Zheng, A. C. & Hu, X. T. Micro-dissolution mechanism and macro-mechanical behavior of red-bed soft rock under dry-wet cycle. Mater. Lett. 362, 136220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2024.136220 (2024).

Zhang, G. D., Ling, S. X., Liao, Z. X., Xiao, C. J. & Wu, X. Y. Mechanism and influence on red-bed soft rock disintegration durability of particle roughness based on experiment and fractal theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 419, 135504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135504 (2024).

Liu, X. M., Zhao, M. H. & Su, Y. H. Grey correlation analysis of collapsibility of red layer soft rock. J. Hunan Univ. 33 (4), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1000-2472.2006.04.004 (2006). (in Chinese).

Zhao, M. H., Zou, X. J. & Zou, P. W. Disintegration characteristics of red sandstone and its filling methods for highway roadbed and embankment. J Mater Civ Eng. 19(5), 404–410 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2007)19:5(404).

Shen, P. W., Tang, H. M. & Wang, D. J. Experimental study on dry and wet cycle disintegration characteristics of purple mudstone. Badong Formation Rock Soil. Mechanics. 38 (7), 1990–1998. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2017.07.019 (2017). (in Chinese).

Xie, X. S., Chen, H. S. & Xiao, X. H. Study on microstructure and softening mechanism of red-bed soft rock under water-rock coupling. J. Eng. Geol. 27 (5), 966–972 (2019). (in Chinese). CNKI:SUN:GCDZ.0.2019-05-004.

Ye, Y. S. et al. Experimental investigation of the particle breakage of coarse-grained materials under impact loading. Transp. Geotech. 40, 100954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2023.100954 (2023).

Liao, J. & Gao, L. Experimental study on compressive strength of the red-bed soft rock highway tunnel’s surrounding rock. In: Second International Conference on Mechanic Automation and Control Engineering. (2011). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5988534

Lu, H., Liu, Q., Chen, C., Wu, Y. & Li, J. Experimental study on mechanical characteristic of weak interlayer in red-bed soft rock slope. Energy Educ. Sci. Technol. 30, 467–474 (2012).

Hou, R. B., Zhang, K., Tao, J., Xue, X. R. & Chen, Y. L. A nonlinear creep damage coupled model for rock considering the effect of initial damage. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 52 (5), 1275–1285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1626-7 (2019).

Hu, B., Cui, A. N., Cui, K., Liu, Y. & Li, J. A novel nonlinear creep model based on damage characteristics of mudstone strength parameters. PLoS One. 16 (6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253711 (2021).

Liu, W. B. & Zhang, S. G. An improved unsteady creep model based on the time dependent mechanical parameters. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 28 (17), 1838–1848. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2020.1712624 (2021).

Zhou, X. P., Pan, X. K. & Berto, F. A state-of-the-art review on creep damage mechanics of rocks. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 45 (3), 627–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/ffe.13625 (2022).

Deng, X. H. et al. The secondary development and application of the improved Nishihara creep model in soft rock tunnels. Buildings 13 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13082082 (2023).

Lyu, C. et al. A creep model for salt rock considering damage during creep. Mech. Time-Depend Mater. 18, 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11043-023-09648-2 (2023).

Lade, P. V., Yamamuro, J. A. & Bopp, P. A. Significance of particle crushing in granular materials. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. 122 (4), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1996)122:4(309) (1996).

O. Hardin, B. Crushing of soil particles. J. Geotech. 111 (10), 1177–1192. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1985)111:10(1177) (1985).

Franklin, J. A. & Chandra, R. The slake-durability test. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 9 (3), 325–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(72)90001-0 (1972).

Dick, J. C., Shakoor, A. & Wells, N. A geological approach toward developing a mudrock-durability classification system. Can. Geotech. J. 31 (1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1139/t94-003 (1994).

Koncagül, E. C. & Santi, P. M. Predicting the unconfined compressive strength of the breathitt shale using slake durability, shore hardness and rock structural properties. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 36 (2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-9062(98)00174-0 (1999).

Feng, R. L., Wang, Y. & Xie, Y. L. Vibration compaction characteristic test of coarse grained soil. China Highway J. 20 (5), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1001-7372.2007.05.004 (2007). (in Chinese).

Zhao, M. H., Chen, B. H. & Su, Y. H. Fractal analysis and numerical simulation of the collapse and crushing process of red bed soft rock. J. Cent. South. Univ. 38 (2), 351–356. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-7207.2007.02.031 (2007). (in Chinese).

Erguler, Z. A. & Shakoor, A. Relative contribution of various Climatic processes in disintegration of clay-bearing rocks. Eng. Geol. 108 (1), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2009.06.002 (2009).

Cao, Z. Y. & Dissertation Study on road performance and vibration compaction technology of coarse grained material on metamorphic soft rock embankment in Qinba Mountain area. Chang’an University (2013).

Wu, S. C., Zhang, S. H. & Zhang, G. Three-dimensional strength Estimation of intact rocks using a modified Hoek-Brown criterion based on a new deviatoric function. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 107, 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.04.050 (2018).

Vinson, T. S., Ahmad, F. & Rieke, R. Factors important to the development of Frost heave susceptibility criteria for coarse-grained soils. Transp. Res. Rec. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148–9062(88)92819-7 (1986).

Bilodeau, J. P., Dore, G. & Pierre, P. Gradation influence on Frost susceptibility of base granular materials. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 9 (6), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10298430802279819 (2008).

Wang, T. L. & Yue, Z. R. Experimental study on effect of fine grain content on Frost heave characteristics of coarse-grained soil. Rock. Soil. Mech. 34 (2), 359–364 (2013). (in Chinese). KI:SUN:YTLX.0.2013-02-011.

She, W. et al. New insights into the Frost heave behavior of coarse grained soils for high-speed railway roadbed: clustering effect of fines. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 167, 102863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2019.102863 (2019).

Song, H. J. et al. The onset of widespread marine red beds and the evolution of ferruginous oceans. Nat. Commun. 8, 399. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00502-x (2017).

Ran, Y. H. et al. Distribution of permafrost in china: an overview of existing permafrost maps. Permafrost Periglac. Process. 23 (4), 322–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.1756 (2012).

Gautam, T. P. & Shakoor, A. Slaking behavior of clay-bearing rocksduring a one-year exposure to natural Climatic conditions. Eng. Geol. 166, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2013.08.003 (2013).

Zhang, Z. H. et al. Disintegration behavior of stronglyweathered purple mudstone in drawdown area of three Gorges reservoir. China Geomophology. 315, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.05.008 (2018).

Liu, W. L. et al. Study on the characteristic strengthand energy evolution law of Badong formation mudstone under watereffect. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 39 (2), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2019.0654 (2020).

Wang, X. Q., Yao, H. Y. & Dai, L. Experimental analysis of soft rock collapse characteristics in red beds in Southern Anhui Province. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 17 (3), 683–691 (2021). (in Chinese).

The Ministry of Railways of the People’s Republic of China. Code for Soil Test of Railway Engineering. TB 10102–2010 (2010). (in Chinese).

Li, S. Z. Dynamic characteristics and operational safety evaluation of ballast track-subgrade system of high-speed railway in high cold region. Dissertation, Harbin Institute of Technology (2022). https://doi.org/10.27061/d.cnki.ghgdu.2022.005477

Fu, H. Y. & Yang, H. T. Study on compaction characteristics and particle fragmentation of carbonaceous mudstone fillers. J. Civil Eng. https://doi.org/10.15951/j.tmgcxb.23090799 (2024). (in Chinese).

Zhang, Z. T. Dynamic characteristics and particle fragmentation evolution of coal gangue subgrade filler under cyclic load. Dissertation, University of Science and Technology of Hunan (2021).

Han, X., Ling, X. Z., Tang, L., Tian, S. & Wang, K. Freeze-heaving and thawing settling characteristics of coarse grained material improved with cement in Island permafrost region. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 42 (05), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.11956/j.issn.1008-0562.2023.05.002 (2023). (in Chinese).

The Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China. Code for engineering geological investigation of frozen soil. GB 50324–2001 (2001). (in Chinese).

Tian, S. et al. Cyclic behaviour of coarse-grained materials exposed to freeze-thaw cycles: experimental evidence and evolution model. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 167, 102815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2019.102815 (2019).

Marsal, R. J. Large-scale testing of rockfill materials. J. Soil. Mech. Found. Div. 93 (2). https://doi.org/10.1061/JSFEAQ.0000958 (1967).

Nakata, Y., Hyde, A. F., Hyodo, M. & Murata, H. A probabilistic approach to sand particle crushing in the triaxial test. Géotechnique 49 (5), 567–583. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1999.49.5.567 (1999).

Teng, J. D., Liu, J. L., Zhang, S. & Sheng, D. C. Frost heave in coarse-grained soils: experimental evidence and numerical modelling. Geotechnique 73 (12), 1100–1111. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeot.21.00182 (2022).

Shojamoghadam, S., Rajaee, A. & Abrishami, S. Impact of various additives and their combinations on the consolidation characteristics of clayey soil. Sci. Rep. 14, 31907. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83385-5 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Key Laboratory of Coal Gangue Resource Utilization and Energy-Saving Building Materials of Liaoning (Grant No.LNTUCEM-2304), Major science and technology projects of the Tibet Autonomous Region (XZ202402ZD0008), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42102311), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (LH2022D016), Chongqing Municipal Construction Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. Chengkezi 2022 No.1–1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiao. Han., and Routong. Sun. collected references, analyzed the data, proposed the research method, prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12, and wrote the main manuscript text (Xiao. Han., and Routong. Sun. contribute equally to this work). Shuang. Tian., and XianZhang. Ling. checked the method, verified its feasibility. Jia’an. Zhou., Jingyi. Liu., and Xipeng. Qin. collected references and prepared Figs. 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, X., Sun, R., Tian, S. et al. Experimental and analytical investigation of Frost heave characteristics in red-bed coarse-grained materials incorporating particle breakage effect. Sci Rep 15, 25416 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10963-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10963-6