Abstract

In this study, a novel magnetic Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 heterojunction catalyst was synthesized via a solvothermal method and evaluated for sulfadiazine (SDZ) degradation under visible-light-assisted peroxymonosulfate (PMS) activation. The Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst was synthesized through a solvothermal method and characterized using morphological, optical, and magnetic techniques. Under optimized conditions (pH = 3.0, 0.4 g/L catalyst dosage, 2 mM PMS, and 75 W/cm² visible light), the system achieved almost complete SDZ degradation (Re = 97.54%, with a rate constant (Kobs) of 5.640E-02 min⁻¹) within 60 min, with a suitable mineralization efficiency (68.06% TOC removal and 77.44% COD removal). Scavenger experiments and EPR confirmed that both SO₄•⁻ and •OH radicals were dominant reactive species for the oxidative process. The catalyst demonstrated robust stability and recyclability over five cycles, with negligible leaching of metal ions. The degradation pathway was elucidated via HPLC/MS, indicating sulfonamide bond cleavage, aromatic ring hydroxylation, and progressive oxidation into low molecular weight acids and inorganic species. The findings highlight the Vis-Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4/PMS system as a promising candidate for sustainable and efficient antibiotic removal in water treatment applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rising concern over pharmaceutical contaminants in aquatic environments has drawn significant attention from the scientific community1. Sulfadiazine (SDZ), a widely used sulfonamide antibiotic, is frequently detected in water systems and poses significant risks to both aquatic ecosystems and human health2. These concerns stem from its persistence in the environment, ability to bioaccumulate, and potential to promote antibiotic resistance3,4. Conventional wastewater treatment methods often face challenges in effectively removing complex pollutants such as sulfadiazine due to its stable chemical composition and its toxic/inhibitory effect on microbial activity. Due to the limitations of conventional treatment methods in addressing persistent pollutants, peroxymonosulfate (PMS)-based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), especially when combined/integrated with photocatalysis, have gained attention as a promising and innovative alternative. These systems have demonstrated significant potential in breaking down resistant contaminants and mitigating associated environmental risks5,6,7. Peroxymonosulfate (PMS) is a powerful oxidant that can be activated to produce sulfate radicals (SO₄⁻•) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) under specific conditions, which exhibit robust oxidative capabilities for degrading a wide range of persistent pollutants, including pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals5. PMS is favored for its high efficiency, stability, and versatility in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for environmental remediation5,8. It can be activated by various energy sources, such as heat or visible light, as well as by transition metals with redox pairs (e.g., Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ and Co²⁺/Co³⁺), further enhancing its applicability in diverse environmental settings9,10. However, the activation of PMS typically requires efficient and stable catalysts to maximize the generation of reactive radicals11. Despite the potential, catalytic materials capable of synergistically activating PMS alongside energy sources like visible light to accelerate degradation rates remain limited12,13. Therefore, the development of novel, environmentally friendly, and highly efficient catalysts is crucial to fully exploit the potential of PMS in environmental cleanup14. Hybrid materials that combine magnetic nanoparticles, such as Fe3O4 NPs, with semiconductors offer distinct advantages in enhancing catalytic performance for this purpose15. Among these semiconductors, ZnIn2S4, a ternary chalcogenide, stands out as an ideal candidate for visible-light photocatalysis due to its narrow bandgap, efficient charge carrier separation, and exceptional stability16,17. These inherent properties make ZnIn2S4 highly effective for various environmental remediation applications, further enhanced by the magnetic properties of Fe3O4 NPs. When ZnIn2S4 is integrated with Fe3O4 NPs, the resulting hybrid catalyst (Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst) benefits from key improvements, including facile magnetic recovery from reaction mixtures using an external magnetic field, enhanced charge separation, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation18,19,20. The combination of Fe₃O₄ and ZnIn₂S₄ forms a heterojunction that facilitates efficient charge separation and promotes faster electron transfer, as Fe₃O₄ acts as a conductive electron acceptor and transporter. This synergy not only suppresses electron–hole recombination but also enhances the availability of active sites for PMS activation under visible light. As a result, the overall photocatalytic performance is improved, enabling efficient pollutant degradation and contributing to the sustainability of the process21,22,23. Recent studies have explored the use of magnetic Fe₃O₄-based composite materials for the degradation of organic pollutants. For instance, Wang et al., 2023 synthesized Fe3O4/ZnO composites for the photocatalytic degradation of amoxycillin under visible light irradiation24. Similar work by Liu et al., 2024 developed Fe3O4/g-C3N4/TiO2 composites for the degradation of tetracycline under the same conditions25. Furthermore, research over the past decade has demonstrated and highlighted the efficacy of ZnIn₂S₄ in removing various antibiotics, including Sulfamethoxazole26. Although magnetic Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst have been studied in various contexts, however their effectiveness in activating PMS for SDZ degradation under visible light irradiation remains underexplored. Hence, taking into account the unique characteristics of Fe3O4 NPs and ZnIn2S4, along with the expected synergistic benefits upon their integration, the following specific objectives were established for this study: (a) Synthesis and Characterization of the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst, its structural and optical properties, (b) Assessment of the catalytic performance of Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 for sulfadiazine degradation under Different conditions (pH, catalyst dosage, PMS concentration, light intensity, and initial SDZ concentration) with kinetic analysis, (c) Evaluation of catalyst reusability and stability through successive sulfadiazine degradation cycles, (d) Investigation of the possible mechanisms involved in SDZ degradation, and (e) Proposal of probable degradation pathway based on intermediate identification and radical scavenging experiments.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

All chemicals were of analytical grade and used as received without further purification. The details of the chemicals and reagents used in this study are provided in Supplementary Material Text 1.

Preparation of Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst

Synthesis of magnetic Fe3O4 NPs

Magnetic Fe3O4 NPs was synthesized using a Albutt et al. method with some modification27. A complete description of the procedure is provided in Supplementary Material, Text 2.

Synthesis of magnetic Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst

The solvothermal method28 was employed to synthesize the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst. Initially, a mixture of In(NO₃)₃·4 H₂O and Zn(NO₃)₂·4 H₂O (with a molar ratio of Zn: In = 1:1) was dissolved in 30 mL of ethylene glycol and a small amount of deionized water under stirring to form a homogeneous and clear solution. Subsequently, an appropriate amount of thiourea as the sulfur source was added to the above solution and the mixture was stirred until the thiourea was fully dissolved. A pre-determined amount of Fe3O4 NPs was then introduced to the solution, and the mixture was sonicated for 30 min to ensure uniform dispersion of the Fe3O4 NPs. The resulting mixture was transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, sealed and heated at 180 °C for 12 h. After the reaction, the autoclave was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The black product was separated from the reaction mixture using an external magnet, washed thoroughly with ethanol and deionized water to remove any residual impurities, and finally dried at 60 °C under vacuum.

Characterization

This information is presented in the Supplementary Material, Text 3.

Experimental procedure

Degradation process

The photocatalytic activity of Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst was evaluated by degradation of SDZ under visible light irradiation. A 300 W Xenon lamp with a 420 nm cut-off filter was used as the source of visible light. A specified amount (0.05–0.8 g/L) of as-prepared photocatalyst was dispersed in 50 mL of SDZ aqueous solution with different initial concentration (10–100 mg/L). Prior to visible light irradiation, the suspension was magnetically stirred for 30 min in the dark to ensure the establishment of an adsorption–desorption equilibrium between the photocatalysts and pollution. Degradation experiments were performed in the predetermined values of pH, catalyst dosage, SDZ concentration, PMS concentration, and light intensity. The initial pH of the solution was adjusted using 0.1 M H₂SO₄ or 0.1 M NaOH. After that, at regular irradiation time intervals, the catalyst was separated from the solution by a magnet and the residual concentration of SDZ in the solution was determined by HPLC. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results are reported as average values ± standard deviations (SD). The degradation efficiency (\(\:{\text{R}}_{\text{e}}\text{\%}\)) of SDZ was calculated using the following equation:

where \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{0}}\) and \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{e}}\) represent the initial and residual concentrations of SDZ (mg/L), respectively. The degradation kinetics of SDZ were analyzed by fitting the experimental data to First-order kinetic model, given by:

where \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{0}}\) is the initial SDZ concentration, \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{t}}\) is the concentration of SDZ at time t, and \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{o}\text{b}\text{s}}\) is the observed First-order rate constant (min⁻¹). The analytical methods of the SDZ concentration, SDZ degradation intermediates, active species, Catalyst stability and reusability and leaching metal ions (In, Zn, and Fe) were described in Supplementary Material, Text 4.

Results and discussion

Characterization of catalyst

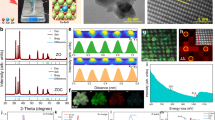

The morphology of ZnIn2S4 before and after modification was investigated by SEM analysis. As shown in Fig. 1a, the pristine ZnIn2S4 exhibited a flower-like microsphere (1–3 μm) composed of ultrathin, cross-linked nanosheets. The smooth and uniform surface morphology, without visible aggregated particles, indicates a relatively clean microstructure29. The flower-like morphology can provide more reactive active sites, and the lamellar petals can reflect light multiple times, which can effectively improve the absorption of light30,31. Figure 1b shows that Fe₃O₄ NPs were randomly distributed on the wafers of ZnIn₂S₄. The overall structure of the Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄ catalyst appeared to be non-uniform, with slight agglomeration observed, likely due to the incorporation of magnetic Fe₃O₄ into the structure32. The pores formed between the nanosheets in the flower-like assemblies facilitated light scattering and enhanced surface area, which is beneficial for photocatalytic activity. In addition, the loading of Fe₃O₄ NPs provided additional active sites, improving light utilization and promoting photocatalytic efficiency21. Elemental mapping of the Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄ catalyst (Fig. S1) revealed the homogeneous distribution of Fe, O, Zn, In, and S elements. Fe and O originated from Fe₃O₄, while Zn, In, and S were attributed to ZnIn₂S₄. The slightly broader mapping distributions of Zn, In, and S compared to Fe and O indicate a lengthwise dispersion of Fe₃O₄ across the ZnIn₂S₄ surface, supporting the successful formation of a composite interface. Furthermore, Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis (Fig. 1c) confirmed the physical attachment of semi-spherical Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles (~ 30–50 nm) to the surface of the flower-like ZnIn₂S₄ structures. Although minor agglomeration was visible, the close interfacial contact between the two components may facilitate heterostructure formation, potentially enhancing charge separation and photocatalytic performance. Figure 1d presents the results of dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis conducted to investigate the hydrodynamic size distributions of pure ZnIn2S4 and the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst. The DLS measurements reveal that the average diameter of pure ZnIn2S4 particles is approximately 1.16 μm, while the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst exhibits a slightly larger size range of 3.12 μm. The increase in particle size upon incorporation of Fe3O4 NPs into the ZnIn2S4 matrix can be attributed to the formation of a heterostructure, where Fe3O4 NPs are either embedded within or attached to the surface of ZnIn2S4. This structural modification leads to the observed enlargement of the hydrodynamic diameter, reflecting the combined contribution of both components. The DLS data further supports the SEM and TEM observations, which indicate the successful integration of Fe3O4 NPs into the ZnIn2S4 framework, forming a stable and well-defined heterostructure. The textural properties of the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst were evaluated using BET surface area and BJH pore size distribution analyses, as shown in Fig. 1e and f. The nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm (type IV pattern) and the observed clear hysteresis loop confirmed the mesoporous nature of the material, with capillary condensation occurring inside the pores. The BJH analysis revealed a dominant pore size of approximately 8.58 nm and a total pore volume of 0.576 cm³/g, confirming a well-developed mesoporous structure. The high BET surface area of 350 m²/g highlights Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst potential for enhanced catalytic activity by providing a greater number of accessible active sites. The presence of an H2/H3-type hysteresis loop suggests a highly intricate pore structure composed of slit-shaped and interconnected pores. This configuration enhances molecular diffusion and optimizes reactant transport, which is crucial for improving catalytic performance and mass transfer efficiency. These favorable textural properties make the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst a highly promising candidate for advanced catalytic applications requiring high surface area, efficient mass transfer, and structural stability. The FTIR spectrum of the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst (Fig. 1g) exhibits distinct absorption bands that confirm the presence of functional groups and interactions between Fe3O4 NPs and ZnIn2S4. A characteristic peak observed at 553 and 764 cm⁻¹ can be confidently assigned to the Fe-O stretching vibrations within the Fe3O4 NPs (magnetite) component33. The peak at 849 cm⁻¹ suggests the presence of Zn-O stretching vibrations within the ZnIn2S4 component34,35. The peaks at 923 cm⁻¹ and 1018 cm⁻¹ are potentially associated with In-S or Zn-S stretching vibrations in ZnIn2S436,37. A peak at 1240 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the bending vibrations of H–O–H from adsorbed water molecules, while a broad band in the 3100–3500 cm⁻¹ region corresponds to hydroxyl (-OH) stretching, suggesting the presence of adsorbed water molecules or surface hydroxylation that may facilitate photocatalytic activity. The presence of peaks at 1356 cm⁻¹ and 1451 cm⁻¹, and 1567 cm⁻¹ likely associated with C-H and C = O vibrations suggest the presence of residual organic compounds originating from the synthesis process or adventitious hydrocarbons adsorbed from the environment. The crystal structure of the ZnIn2S4, Fe3O4 NPs and Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst were characterized by XRD analysis in the range of 2θ = 10° to 80° and their patterns are shown in Fig. 1h. Pure ZnIn2S4 exhibits a series of well-defined diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 21.81°, 27.72°, 30.45°, 39.53°, 47.55°, 52.79°, 55.18°, and 77.3°. These peaks are assigned to the crystallographic planes (006), (102), (104), (108), (110), (116), (021), and (440), respectively. The observed pattern matches perfectly with the standard JCPDS card No. 65-2023, confirming that ZnIn2S4 crystallizes in a hexagonal structure38. This structural confirmation is critical because the hexagonal (layered) nature of ZnIn2S4 contributes to its unique optical and electronic properties, which are essential for photocatalytic applications. The Fe3O4 NPs display characteristic diffraction peaks at 35.96°, 43.09°, 58.25°, and 64.82° corresponding to the (311), (400), (511), and (440) planes, respectively. These peaks are in excellent agreement with the standard pattern for cubic spinel structured Fe3O4 NPs (JCPDS file no. 19–0629), confirming the high crystallinity and phase purity of the nanoparticles. Similar diffraction patterns have been reported in other studies involving Fe3O4 NPs39,40. The clear presence of characteristic peaks from both Fe3O4 NPs and ZnIn2S4in the Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 catalyst confirms the successful synthesis of the intended composite material. The presence of peaks from both constituent materials without significant shifts and disappearances suggests that both components maintain their original crystal structures within the composite. Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM) was employed to investigate the magnetic properties of Fe3O4 NPs and a Fe3O4- ZnIn2S4 catalyst (Fig. 1i). The resulting magnetization curves exhibited S-shaped hysteresis loops, characteristic of superparamagnetic or soft ferromagnetic materials. Pure Fe3O4 NPs demonstrated a saturation magnetization (Ms) of 73.34 emu/g and near-zero coercivity (Hc), confirming its soft magnetic nature. Upon incorporating ZnIn2S4, the composite’s Ms decreased to 50.97 emu/g. This reduction is attributed to the presence of the non-magnetic ZnIn2S4 component, which dilutes the overall magnetic moment. Furthermore, this decrease suggests potential interfacial interactions between Fe3O4 NPs and ZnIn2S4, which could influence charge transfer and consequently affect catalytic efficiency. Despite the reduced Ms, the composite retained its soft magnetic behavior, as evidenced by the low coercivity, ensuring its suitability for applications requiring external field-assisted recovery and recyclability.

Optical and electronic properties of catalyst

The UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectrum (DRS) of Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄ (Fig. 2a) displays broad visible-light absorption from 400 to 650 nm, with an absorption edge near 530 nm. The corresponding Tauc plots (Fig. 2b) indicate a narrowed direct bandgap of approximately 1.92 eV compared to that of pristine ZnIn₂S₄ (typically 2.3–2.6 eV)41,42. This bandgap narrowing can be attributed to the interaction between Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles and ZnIn₂S₄, possibly due to orbital overlap at the interface or the presence of sub-band energy levels introduced by Fe₃O₄43,44. However, it is important to note that UV–Vis DRS alone cannot confirm electron migration or heterojunction type. To more accurately determine the band structure alignment, Mott–Schottky (M–S) analysis was employed (Fig. 2c). The composite exhibited n-type semiconducting behavior with a flat band potential of − 0.55 V vs. Ag/AgCl, suggesting a negatively shifted conduction band. This shift supports the presence of favorable band alignment for charge transfer and confirms heterojunction formation45, as also observed in similar systems46. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra (Fig. 2d) were recorded to evaluate the recombination behavior of photogenerated charge carriers. Compared to pristine ZnIn₂S₄, the Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄ composite exhibits significantly quenched PL intensity, indicating reduced radiative recombination and improved charge separation. This supports the hypothesis of efficient interfacial charge transfer upon heterojunction formation. As recommended in the literature, PL comparison between pristine and composite samples is essential to validate the heterojunction effect47,48,49,50.

Effect of operational parameters and kinetic study

Effect of pH

The influence of initial pH on SDZ degradation by the Vis/Fe₃O₄-ZnIn₂S₄/PMS system was evaluated in the range of 3 to 11. As shown in Fig. 3a and Fig. S2a, the maximum removal efficiency (75.09%) and the highest rate constant (Kobs = 1.431E-02 min⁻¹) were achieved at pH 3. This enhanced performance under acidic conditions is attributed to improved PMS activation and favorable electrostatic interactions between the catalyst and the negatively charged SDZ and PMS species. Notably, the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the catalyst was determined to be 2.78 (Fig. S3), indicating that at pH 3, the catalyst surface is slightly positively charged, which promotes adsorption of anionic species such as sulfadiazine (pKa ~6.5, partially deprotonated at pH 3) and the HSO₅⁻ ion (pKa ~9.4, predominantly present in its anionic form). As the pH increased to neutral and alkaline levels, the degradation efficiency and reaction rate decreased significantly. At pH 7 and 11, SDZ removal dropped to 61.67% (Kobs = 1.023E-02 min⁻¹) and 23.23% (Kobs = 2.621E-03 min⁻¹), respectively. This decline can be attributed to reduced PMS protonation, resulting in less reactive species formation, electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged catalyst surface and anionic species, and possible catalyst deactivation due to metal ion precipitation or surface passivation under alkaline conditions. Overall, pH 3 was identified as the optimal condition for SDZ degradation. Similar trends have been reported in previous studies51,52.

Effect of sulfadiazine concentration

The influence of initial SDZ concentration (10–100 mg/L) on degradation performance was assessed under at pH 3, 0.3 g/L catalyst, 1 mM PMS, 60 W/cm² light. As shown in Fig. 3b and Fig. S2b, a clear inverse relationship was observed between SDZ concentration and degradation efficiency. The maximum removal efficiency (84.20%) and the highest rate constant (Kobs = 1.906E-02 min⁻¹) were obtained at the lowest tested concentration of 10 mg/L. This can be attributed to the sufficient availability of active sites and reactive species relative to the concentration of pollutant molecules, enabling more effective catalytic interactions and enhanced degradation efficiency. As the SDZ concentration increased to 50 and 75 mg/L, efficiencies declined to 75.09% (Kobs = 1.431E-02 min⁻¹) and 67.07% (Kobs = 1.100E-02 min⁻¹), respectively, mainly due to competition for active sites and depletion of oxidants. At 100 mg/L, removal dropped to 35.02% (Kobs = 4.398E-03 min⁻¹), likely due to active site saturation, light attenuation, and scavenging of reactive species. These findings align with prior studies53,54,55, confirming that excess pollutant loading impairs the efficiency of radical-based degradation systems. Therefore, 10 mg/L was identified as the optimal SDZ concentration in this system.

Effect of catalyst dosage

The effect of catalyst dosage (0.05–0.8 g/L) on SDZ degradation was evaluated in the Vis–Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄/PMS system. As shown in Fig. 3c and Fig. S2c, increasing the dosage improved performance up to an optimal value of 0.4 g/L, achieving 91.78% removal (Kobs = 2.655E-02 min⁻¹), a 3.7-fold increase compared to 0.05 g/L (24.53%). This enhancement is primarily attributed to the improved dispersion, increased number of active sites and improved light absorption, which facilitate more efficient PMS activation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation56. However, further increasing the dosage beyond 0.4 g/L led to a decline in performance, likely due to light scattering, catalyst aggregation, and mass transfer limitations, which hinder effective photoexcitation and surface reactions57. These findings are in agreement with earlier studies58,59, which similarly reported an optimal catalyst loading beyond which degradation efficiency plateaued or declined. Therefore, 0.4 g/L was identified as the optimal dosage, balancing catalytic activity and system efficiency for subsequent experiments.

Effect of visible light intensity

The effect of visible light intensity on SDZ degradation was evaluated in the range of 40–90 W/cm²,, and the results are presented in Fig. 3d and Fig. S2d. The degradation efficiency increased significantly with light intensity, rising from 73.11% at 40 W/cm² to a maximum of 96.45% (Kobs= 3.589E-02 min⁻¹) at 75 W/cm². This enhancement is attributed to the increased photon flux, which boosts the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by promoting charge separation on the catalyst surface and activating peroxymonosulfate (PMS). Similar trends were reported in studies using Cu₂O@zeolite/PDS51 and ZnFe₂O₄/biochar/PMS58, where visible light irradiation significantly enhanced radical generation and SDZ degradation. However, further increasing the intensity to 90 W/cm² led to only marginal improvement (96.55%, Kobs = 3.620E-02 min⁻¹), likely due to light scattering and catalyst instability. Thus, 75 W/cm² was selected as the optimal intensity balancing efficiency, stability and energy conservation.

Effect of peroxymonosulfate concentration

The influence of PMS concentration (1–6 mM) on SDZ degradation is illustrated in Fig. 3e and Fig. S2e. Increasing the PMS level from 1 to 2 mM enhanced degradation efficiency to 100%, accompanied by a ~ 63.6% increase in the apparent rate constant (Kobs), mainly due to increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through catalyst-mediated PMS activation60,61. However, concentrations above 2 mM resulted in a slight decline in efficiency. This inhibitory effect is attributed to the well-documented self-scavenging of radicals by excess PMS molecules (e.g., SO₄•⁻ + HSO₅⁻ → SO₅•⁻ + HSO₄⁻), which converts highly reactive radicals into less effective species. Similar behavior was reported in persulfate-based AOPs studies, where excessive PMS reduced degradation efficiency due to radical quenching effects53,58. Therefore, a PMS concentration of 2 mM was identified as the optimal condition for achieving complete degradation without wasteful consumption of the oxidant.

Sulfadiazine degradation under various systems

The degradation performance of SDZ was assessed under various catalytic systems, and the results are summarized in Fig. S4. Direct photolysis under visible light showed limited degradation (11.83% at 90 min), confirming that the energy from visible photons alone is insufficient for rapid SDZ transformation. PMS alone also led to minimal removal (4.73%), highlighting its weak oxidizing ability without activation. ZnIn₂S₄ in the dark exhibited 15.05% removal, likely due to limited adsorption or weak catalytic activity. Upon visible light irradiation (Vis-ZnIn₂S₄), the efficiency increased significantly (54.39%), as ZnIn₂S₄ generated electron–hole pairs that led to ROS formation9. Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles demonstrated 12.77% removal in the dark, primarily via adsorption. When irradiated with visible light (Vis-Fe₃O₄), removal improved to 39.88%, suggesting that Fe₃O₄ can contribute to photocatalytic activity, albeit at a lower efficiency than ZnIn₂S₄. This behavior is related to the narrow band gap of Fe₃O₄ (~ 0.1 eV), which allows limited visible light absorption. Although Fe₃O₄ is not a conventional semiconductor, its unique electronic structure enables photoexcited charge carriers and supports photo-Fenton-like processes. The redox cycling of Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ on its surface also facilitates PMS activation, producing reactive sulfate and hydroxyl radicals. The PMS–ZnIn₂S₄ system reached 48.32% removal, indicating ZnIn₂S₄’s ability to activate PMS via surface electron transfer, even in the absence of light58. PMS–Fe₃O₄ reached 30.90%, confirming Fe₃O₄’s effectiveness as a PMS activator through Fenton-like mechanisms. Notably, the Vis-Fe₃O₄-ZnIn₂S₄ heterojunction achieved 89.07% removal, outperforming the individual catalysts. This improvement is attributed to enhanced charge separation across the heterojunction. The conduction band (CB) of ZnIn₂S₄ (~–0.94 V vs. NHE) is more negative than that of Fe₃O₄, facilitating electron transfer and reducing charge recombination. Fe₃O₄ also acts as an electron sink, further prolonging carrier lifetime and enhancing ROS generation21,62. In dark conditions, PMS–Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄ led to 84.31% removal, indicating a synergistic PMS activation by both Fe₃O₄ and ZnIn₂S₄. The combination of their activation pathways (Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ cycling and surface-induced electron transfer) enhances radical formation9,63. Finally, the Vis–Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄/PMS system achieved complete SDZ degradation (100% at 75–90 min), due to the combined effects of photocatalytic charge separation, light-induced ROS generation, and dual-site PMS activation. This synergy highlights the system’s promise for advanced water treatment applications64,65,66,67.

Recovery, reusability and mineralization assessment

To evaluate the stability and reusability of the Vis-Fe₃O₄-ZnIn₂S₄/PMS system, five consecutive degradation cycles of sulfadiazine were performed under optimized conditions (10 mg/L SDZ, 2 mM PMS, 0.4 g/L catalyst, pH 3.0- and 60-min contract time). As shown in Fig. 4a–c, the degradation efficiency decreased by 32.47% after five cycles, accompanied by a reduction in the rate constant from 5.64E-02 to 1.25E-02 min⁻¹. This decline in activity is likely due to the progressive adsorption of SDZ and its degradation intermediates on the catalyst surface, which hinders access to active sites and reduces photon absorption efficiency. Similar behavior has been reported in other ZnIn₂S₄- and Fe₃O₄-based photocatalysts after multiple reuses68,69,70. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) analysis was conducted to monitor potential leaching of metal ions from the catalyst. After five cycles, Fe (0.18 mg/L) and Zn (0.5 mg/L) were detected at low levels, while indium remained below the detection limit. These results confirm the structural integrity and chemical stability of the composite under operating conditions. The extent of SDZ mineralization was evaluated through total organic carbon (TOC) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) measurements (Fig. 4d–e). A 68.06% TOC reduction and 77.44% COD reduction were achieved, indicating that the process not only degraded the parent compound but also led to substantial breakdown of intermediates into simpler and more biodegradable products. The greater COD removal compared to TOC suggests that partially oxidized intermediates were formed, contributing to the overall oxidation load. These findings highlight the capability of the system to achieve efficient degradation and partial mineralization over repeated use, with minimal secondary pollution.

Identification of dominant reactive oxygen species in sulfadiazine degradation

To elucidate the degradation mechanism of SDZ, radical scavenger experiments and EPR analysis were conducted to identify the key reactive oxygen species (ROS) involved in the Vis–Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄/PMS system. As shown in Fig. 4f–g, the most significant inhibition occurred with methanol (MeOH, 72.11%), indicating a dominant role of both hydroxyl (•OH) and sulfate (SO₄•⁻) radicals. Tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) also caused strong inhibition (67.51%), confirming the major contribution of •OH. EDTA, a scavenger of photogenerated holes, led to moderate inhibition (53.54%), suggesting a supporting role for h⁺71,72,73. In contrast, the inhibitory effect of benzoquinone (BQ), a superoxide radical (O₂•⁻) scavenger, was relatively low (43.98%), indicating that O₂•⁻ plays a minor role in SDZ degradation. This is further supported by the Fig. 4g (inset pie chart), which visualizes the relative contribution of each scavenger based on its inhibitory effect. In fact, pie chart visual summary complements the main plot by quantitatively comparing the effect of each quencher on the overall degradation efficiency While •OH and SO₄•⁻ were the dominant species, the involvement of O₂•⁻ appears limited under the present conditions. Moreover, EPR spectra (Fig. 4h) clearly show the presence of DMPO–•OH and DMPO–SO₄•⁻ adducts, whereas no characteristic signals for O₂•⁻ were observed. Therefore, although BQ results suggest a potential minor contribution from O₂•⁻, its generation was not directly confirmed and may result from secondary processes, such as electron transfer to dissolved oxygen. These findings collectively suggest that the degradation process is primarily driven by •OH and SO₄•⁻ radicals, supported by h⁺, while the role of O₂•⁻ is minor and likely not a major contributor in this system.

Proposed mechanism of sulfadiazine degradation by Vis-Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4/PMS system

The degradation of SDZ in the Vis–Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄/PMS system is governed by a synergistic mechanism involving visible-light-driven photocatalysis and peroxymonosulfate (PMS) activation. Upon visible light irradiation, ZnIn₂S₄ absorbs photons and generates electron–hole pairs (e⁻/h⁺) due to its narrow bandgap. The conduction band (CB) potential of ZnIn₂S₄ (− 0.94 V vs. NHE) is more negative than both the CB of Fe₃O₄ (− 0.1 V vs. NHE) and the standard reduction potential of Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ (+ 0.77 V vs. NHE), which thermodynamically favors electron transfer from ZnIn₂S₄ to Fe₃O₄. As a result, photogenerated electrons in ZnIn₂S₄ reduce surface Fe(III) species to Fe(II), as shown in Eq. (3):

These Fe(II) species subsequently activate PMS (HSO₅⁻), yielding highly oxidative sulfate radicals (SO₄•⁻), as described in Eq. (4):

Simultaneously, the photogenerated holes in the valence band (VB) of ZnIn₂S₄ (1.32 V vs. NHE) can oxidize water to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH):

The •OH and SO₄•⁻ radicals are both powerful oxidants capable of non-selective attack on SDZ molecules. SO₄•⁻ can further undergo hydrolysis to generate additional •OH (Eq. 6):

Furthermore, the Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox couple facilitates a sustainable catalytic cycle for continuous PMS activation. In addition to the classical reaction of Fe(II) with PMS to generate SO₄•⁻, Fe(III) can also participate in PMS activation pathways. Specifically, Fe(III) reacts with HSO₅⁻ to regenerate Fe(II) while producing reactive species such as hydroperoxyl radicals (HO₂•) and peroxymonosulfate radicals (SO₅•⁻), as shown in Eqs. (7) and (8):

Control experiments (Fig. S4) confirmed that even in the absence of light and ZnIn₂S₄, the Fe₃O₄/PMS system could appreciable SDZ degradation, validating the redox cycle and PMS-activating ability of Fe₃O₄. Although superoxide radicals (O₂•⁻) are occasionally generated via electron transfer to dissolved oxygen, their contribution in this system was found to be minimal. This is evidenced by the relatively low inhibition in scavenger tests using benzoquinone (BQ) and the absence of DMPO–O₂•⁻ signals in EPR spectra. Therefore, while O₂•⁻ may form under specific conditions, its role in the overall degradation pathway is negligible. Collectively, the degradation process is primarily driven by •OH, SO₄•⁻, and photogenerated holes (h⁺), facilitated by the efficient charge separation in the Fe₃O₄–ZnIn₂S₄ heterojunction under visible light. This mechanism underscores the synergistic effects of photoexcitation and PMS activation in generating a variety of reactive species essential for efficient antibiotic removal. The overall process is schematically illustrated in Fig. S5.

Proposed sulfadiazine degradation pathways

To elucidate the degradation mechanism of sulfadiazine (SDZ) in the Vis-Fe₃O₄-ZnIn₂S₄/PMS system, both the identification of intermediates and the role of different reactive oxygen species (ROS) were examined. Based on the results, four primary and interrelated degradation pathways were identified, all driven by ROS including sulfate radicals (SO₄•⁻), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and photoinduced holes (h⁺). The first pathway involves the cleavage of the sulfonamide group (-SO₂-NH₂), which is particularly susceptible to electrophilic attack by SO₄•⁻ and •OH. This leads to the formation of sulfanilic acid (m/z 172), aniline (m/z 93), and pyrimidine derivatives (m/z 126). This mechanism is consistent with prior studies using UV/O₃ and Fe⁰/PS systems74,75. The second pathway comprises the oxidative ring-opening of the pyrimidine moiety, producing low-molecular-weight organic acids such as formic (m/z 46), acetic (m/z 60), and oxalic acids (m/z 90), alongside 2-aminopyrimidine (m/z 94), a key transformation product. The third pathway includes oxidative deamination of the -NH₂ group within the SDZ molecule or its intermediates, resulting in nitrogen-containing species such as NO₂⁻, NO₃⁻, and NH₄⁺.This sequence reflects the progressive mineralization of nitrogen from the parent compound76. The fourth pathway is the hydroxylation of aromatic rings (e.g., aniline derivatives), leading to hydroxylated intermediates (m/z 243) that undergo further oxidative breakdown and eventual mineralization. Importantly, these pathways are not mutually exclusive but are closely interlinked and proceed synergistically due to the concurrent presence of multiple ROS in the reaction environment. As recently highlighted by Malefane et al.77, systems combining PMS activation and photocatalytic components can benefit from dual ROS generation: sulfate radicals generated via PMS activation and hydroxyl radicals/holes produced through photoexcitation. In present system, PMS is activated by Fe₃O₄ and photogenerated electrons from ZnIn₂S₄, generating SO₄•⁻, while the valence band holes oxidize surface water molecules to form •OH. The coexistence of SO₄•⁻ and •OH ensures that both selective and non-selective oxidation mechanisms occur concurrently—SO₄•⁻ preferentially attacks electron-rich groups, while •OH provides broader oxidative coverage, enhancing overall degradation and mineralization efficiency. This integrated oxidative environment allows for the stepwise conversion of SDZ and its intermediates into final inorganic products such as CO₂, H₂O, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, NO₂⁻, and NH₄⁺. The synergistic interaction among ROS not only accelerates the breakdown of complex structures but also enhances the completeness of mineralization. The overall degradation process is illustrated in Fig. 5, summarizing the proposed transformation routes.

Conclusion

This work successfully developed and applied a visible-light-driven Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 heterojunction catalyst for the efficient activation of peroxymonosulfate (PMS) to degrade sulfadiazine (SDZ), a persistent sulfonamide antibiotic. The integration of magnetic Fe3O4 NPs with ZnIn2S4 not only facilitated magnetic recovery but also enhanced interfacial charge separation and ROS generation. The system demonstrated excellent photocatalytic activity under optimized conditions, achieving almost complete degradation of SDZ and significant mineralization (TOC and TOC removal). Scavenger and EPR analyses verified that •OH and SO₄•⁻ radicals are the dominant ROS, while LC-MS revealed multiple degradation pathways involving sulfonamide cleavage and oxidation of the aromatic and amino groups. Despite a gradual decline in efficiency after five reuse cycles due to surface fouling, the catalyst maintained good structural integrity and negligible metal leaching. This study provides strong evidence for the applicability of Fe3O4-ZnIn2S4 as a multifunctional, magnetically recoverable catalyst in advanced oxidation processes targeting recalcitrant pharmaceutical pollutants in water.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bu, J. et al. Waste coal Cinder catalyst enhanced electrocatalytic oxidation and persulfate advanced oxidation for the degradation of sulfadiazine. Chemosphere 303, 134880 (2022).

Zheng, H. et al. Dissecting the ecological risks of sulfadiazine degradation intermediates under different advanced oxidation systems: from toxicity to the fate of antibiotic resistance genes. Sci. Total Environ., 941, 173678 (2024).

Dong, F. X. et al. Removal of antibiotics sulfadiazine by a Biochar based material activated persulfate oxidation system: performance, products and mechanism. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 157, 411–419 (2022).

Rana, S. et al. Recent advances in photocatalytic removal of sulfonamide pollutants from waste water by semiconductor heterojunctions: a review. Mater. Today Chem. 30, 101603 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Highly efficient activation of peroxymonosulfate for rapid sulfadiazine degradation by Fe3O4@ Co3S4, separation and purification technology, 307 122755. (2023).

Sun, Q., Wang, X., Liu, Y., Xia, S. & Zhao, J. Activation of peroxymonosulfate by a floating oxygen vacancies-CuFe2O4 photocatalyst under visible light for efficient degradation of sulfamethazine. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153630 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Peroxymonosulfate activation through 2D/2D Z-scheme CoAl-LDH/BiOBr photocatalyst under visible light for Ciprofloxacin degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 420, 126613 (2021).

Wang, J. & Liang, M. Fe3O4@ BPC nanocatalyst: enhanced activation of peroxymonosulfate for effective degradation of Norfloxacin. Mater. Lett. 352, 135223 (2023).

Li, X. et al. The enhanced mechanism of ZnIn2S4-CoFe2O4-BC activated peroxomonosulfate under visible light for the degradation of fluoroquinolones. Sep. Purif. Technol. 356, 129927 (2025).

Malefane, M. E., Mafa, P. J., Nkambule, T. T. I., Managa, M. E. & Kuvarega, A. T. Modulation of Z-scheme photocatalysts for pharmaceuticals remediation and pathogen inactivation: design devotion, concept examination, and developments. Chem. Eng. J. 452, 138894 (2023).

Qin, Y., Ahmed, A., Iqbal, S. & Usman, M. Construction of β-cyclodextrin modified Fe3O4 composites with enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation towards efficient degradation of Norfloxacin. Mol. Catal. 547, 113368 (2023).

Poomipuen, K. et al. Dual activation of peroxymonosulfate using MnFe2O4/g-C3N4 and visible light for the efficient degradation of steroid hormones: performance, mechanisms, and environmental impacts. ACS Omega. 8, 36136–36151 (2023).

Mohamadpour, F. & Amani, A. M. Photocatalytic systems: reactions, mechanism, and applications. RSC Adv. 14, 20609–20645 (2024).

Ijaz, I. et al. Activation of persulfate, peroxymonosulfate, and peroxydisulfate using metal-organic framework catalysts for degradation of antibiotics: identification, quantification, interconversion, and transformation of reactive species. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 21, 112838. (2024).

Arulkumar, E. & Thanikaikarasan, S. Structural feature, morphology and optical properties of g-C3N4 decorated CuO-Fe3O4 nano composite for electrocatalytic and photocatalytic applications. Diam. Relat. Mater., 147, 111294. (2024).

Li, S. et al. Antibacterial Z-scheme ZnIn2S4/Ag2MoO4 composite photocatalytic nanofibers with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. Chemosphere 308, 136386 (2022).

Liu, C., Zhang, Q. & Zou, Z. Recent advances in designing ZnIn2S4-based heterostructured photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 139, 167–188 (2023).

Nie, C. et al. Efficient peroxymonosulfate activation by magnetic MoS2@ Fe3O4 for rapid degradation of free DNA bases and antibiotic resistance genes. Water Res. 239, 120026 (2023).

Yueyu, S. The synergistic degradation of pollutants in water by photocatalysis and PMS activation. Water Environ. Res. 95, e10927 (2023).

Anwer, H. & Park, J. W. Lorentz force promoted charge separation in a hierarchical, bandgap tuned, and charge reversible NixMn (0.5 – x) O photocatalyst for sulfamethoxazole degradation. Appl. Catal. B. 300, 120724 (2022).

Sun, H., Wang, L., Wang, X., Dong, Y. & Pei, T. A magnetically recyclable Fe3O4/ZnIn2S4 type-II heterojunction to boost photocatalytic degradation of Gemifloxacin. Appl. Surf. Sci. 656, 159674 (2024).

Malefane, M. E., Mafa, P. J., Managa, M., Nkambule, T. T. & Kuvarega, A. T. Understanding the principles and applications of dual Z-scheme heterojunctions: how Far can we go? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 1029–1045 (2023).

Malefane, M. E. Co3O4/Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I C-Scheme heterojunction for degradation of organic pollutants by Light-Emitting diode irradiation. ACS Omega. 5, 26829–26844 (2020).

Wang, J., Feng, J. & Wei, C. Molecularly imprinted polyaniline immobilized on Fe3O4/ZnO composite for selective degradation of Amoxycillin under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 609, 155324 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of Tetracycline with Fe3O4/g-C3N4/TiO2 catalyst under visible light. Carbon Lett. 34, 75–83 (2024).

He, G. et al. Layered metal chalcogenide ZnIn2S4 anchored with nickel metal Dots for efficient photocatalytic production of hydrogen peroxide and degradation of sulfamethoxazole. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 63, 3827–3836 (2024).

Albutt, N., Sonsupup, S., Sinprachim, T. & Thonglor, P. Synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles coated with Chitosan for biomedical applications. Key Eng. Mater. 1005, 49–57 (2024).

Kale, B. B., Bhirud, A. P., Baeg, J. O. & Kulkarni, M. V. Template free architecture of hierarchical nanostructured ZnIn2S4 Rose-Like flowers for solar hydrogen production. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 17, 1447–1454 (2017).

Jo, W. K., Lee, J. Y. & Natarajan, T. S. Fabrication of hierarchically structured novel redox-mediator-free ZnIn 2 S 4 marigold flower/bi 2 WO 6 flower-like direct Z-scheme nanocomposite photocatalysts with superior visible light photocatalytic efficiency. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 1000–1016 (2016).

He, L., Zhang, W., Liu, S. & Zhao, Y. Three-dimensional porous N-doped graphitic carbon framework with embedded CoO for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Appl. Catal. B. 298, 120546 (2021).

Jiang, X. et al. Preparation of magnetically retrievable flower-like AgBr/BiOBr/NiFe2O4 direct Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst with enhanced visible-light photoactivity. Colloids Surf., A. 633, 127880 (2022).

Yang, Z., Chen, Y., Xu, L., Liu, C. & Jiang, Z. A novel Z-scheme Bi4O5I2/NiFe2O4 heterojunction photocatalyst with reliable recyclability for Rhodamine B degradation. Adv. Powder Technol. 32, 4522–4532 (2021).

Mpelane, S., Mketo, N., Mlambo, M., Bingwa, N. & Nomngongo, P. N. One-step synthesis of a Mn-doped Fe2O3/GO core–shell nanocomposite and its application for the adsorption of Levofloxacin in aqueous solution. ACS Omega. 7, 23302–23314 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. In Situ Growth of Seaweed-Like Znin2s4 Onto Zif-8@ Pan Nanofiber Membrane for Efficient Separation of Emulsified Oily Wastewater and Highly Enhanced Photocatalytic Self-Cleaning Function, Available at SSRN 4910984.

Liu, S. et al. Step-scheme/Mott-Schottky integrated heteroiunctions inBiFeO3/ZnIn2S4/Ag hollow nanospheres: Facilitating efficient piezo-photocatalytic activation of peroxydisulfate to enhance nizatidinedegradation and antibacterial activity, Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 45, 686:45–62.

Khan, I. et al. RETRACTED: dimensionally intact construction of ultrathin S-Scheme CuFe2O4/ZnIn2S4 heterojunctional photocatalysts for CO2 photoreduction. Inorg. Chem. 63, 14004–14020 (2024).

Jin, J. et al. Constructing CuNi dual active sites on ZnIn 2 S 4 for highly photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Catal. Sci. Technol. 11, 2753–2761 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Facile construction of 2D/2D ZnIn2S4-based bifunctional photocatalysts for H2 production and simultaneous degradation of Rhodamine B and Tetracycline. Nanomaterials 13, 2315 (2023).

Irianti, F. et al. Characterization structure of Fe3O4@ PEG-4000 nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation method, in: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, IOP Publishing, p. 012014. (2021).

Asab, G., Zereffa, E. A. & Abdo Seghne, T. Synthesis of silica-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles by microemulsion method: characterization and evaluation of antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Biomaterials. 2020, 4783612 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Coupling ZnIn2S4 nanosheets with MoS2 Hollow nanospheres as visible-light-active bifunctional photocatalysts for enhancing H2 evolution and RhB degradation. Inorg. Chem. 62, 7111–7122 (2023).

Cai, J. et al. ZnIn2S4/MOF S-scheme photocatalyst for H2 production and its femtosecond transient absorption mechanism. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 197, 183–193 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. A mini-review on ZnIn2S4-Based photocatalysts for energy and environmental application. Green. Energy Environ. 7, 176–204 (2022).

Malefane, M. E., Feleni, U. & Kuvarega, A. T. A tetraphenylporphyrin/wo 3/exfoliated graphite nanocomposite for the photocatalytic degradation of an acid dye under visible light irradiation. New J. Chem. 43, 11348–11362 (2019).

Jiang, D. et al. MoS2/SnNb2O6 2D/2D nanosheet heterojunctions with enhanced interfacial charge separation for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 536, 1–8 (2019).

Malefane, M. E., Managa, M., Nkambule, T. T. I. & Kuvarega, A. T. Attuned band structure in triple S-scheme heterojunctions for Naproxen degradation under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 497, 155094 (2024).

LiK et al. Investigating the performance and stability of Fe3O4/Bi2MoO6/g-C3N4 magnetic photocatalysts for the photodegradation of sulfonamide antibiotics under visible light irradiation. Processes 11, 1749 (2023).

Rivera-Enríquez, C. et al. Velásquez-Ordoñez, quenching effect in luminescent and magnetic properties of Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3/Y2O3. Eu3 + nanocomposites Ceram. Int. 49, 41133–41141 (2023).

Malefane, M., Feleni, U., Mafa, P. & Kuvarega, A. Fabrication of direct Z-scheme Co3O4/BiOI for ibuprofen and Trimethoprim degradation under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 514, 145940 (2020).

Malefane, M. E., Managa, M., Nkambule, T. T. & Kuvarega, A. T. s-scheme3D/3D Bi0/BiOBr/P doped g‐C3 N4 with oxygen vacancies (Ov) for photodegradation of pharmaceuticals: In‐situ H2O2 production and plasmon induced stability. ChemSusChem 18, e202401471 (2025).

Zhenyu, L. et al. Visible light enhanced the degradation of sulfadiazine with persulfate activated by Cu2O@ zeolite. Environ. Pollutants Bioavailab. 36, 2387687 (2024).

Roy, K. & Moholkar, V. S. Sulfadiazine degradation by combination of hydrodynamic cavitation and Fenton–persulfate: parametric optimization and deduction of chemical mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 25569–25581 (2023).

Lu, H., Feng, W. & Li, Q. Degradation efficiency analysis of sulfadiazine in water by ozone/persulfate advanced oxidation process. Water 14, 2476 (2022).

Roy, K., Agarkoti, C., Malani, R. S., Thokchom, B. & Moholkar, V. S. Mechanistic study of sulfadiazine degradation by ultrasound-assisted Fenton-persulfate system using yolk-shell Fe3O4@ hollow@ mSiO2 nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 217, 115522 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. Photodegradation performance and mechanism of sulfadiazine in Fe (III)-EDDS-activated persulfate system. Environ. Technol. 44, 3518–3531 (2023).

Zhu, L., Shi, Z., Deng, L. & Duan, Y. Efficient degradation of sulfadiazine using magnetically recoverable MnFe2O4/δ-MnO2 hybrid as a heterogeneous catalyst of peroxymonosulfate. Colloids Surf., A. 609, 125637 (2021).

Zheng, X. et al. Metal-based catalysts for persulfate and peroxymonosulfate activation in heterogeneous ways: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 429, 132323 (2022).

Wang, Y., Gan, T., Xiu, J., Liu, G. & Zou, H. Degradation of sulfadiazine in aqueous media by peroxymonosulfate activated with biochar-supported ZnFe 2 O 4 in combination with visible light in an internal loop-lift reactor. RSC Adv. 12, 24088–24100 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. Activation of peroxymonosulphate using a highly efficient and stable ZnFe2O4 catalyst for Tetracycline degradation. Sci. Rep. 13, 13932 (2023).

Kohantorabi, M., Moussavi, G., Mohammadi, S., Oulego, P. & Giannakis, S. Photocatalytic activation of peroxymonosulfate (PMS) by novel mesoporous ag/zno@ NiFe2O4 nanorods, inducing radical-mediated acetaminophen degradation under UVA irradiation. Chemosphere 277, 130271 (2021).

Wang, A. et al. Enhanced and synergistic catalytic activation by photoexcitation driven S – scheme heterojunction hydrogel interface electric field. Nat. Commun. 14, 6733 (2023).

Kubiak, A. Comparative study of TiO2–Fe3O4 photocatalysts synthesized by conventional and microwave methods for metronidazole removal. Sci. Rep. 13, 12075 (2023).

Xie, Y., Yang, X., Chen, J., Ma, Y. & Li, Y. Efficient peroxymonosulfate activation by magnetic Fe3O4/ZIF-67/Ti3C2Tx composites for Tetracycline degradation. Mater. Today Commun. 43, 111658 (2025).

Huidobro, L., Bautista, Q., Alinezhadfar, M., Gómez, E. & Serrà, A. Enhanced visible-light-driven peroxymonosulfate activation for antibiotic mineralization using electrosynthesized nanostructured bismuth oxyiodides thin films. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 112545 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Recent advances in photodegradation of antibiotic residues in water. Chem. Eng. J. 405, 126806 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. In-situ-construction of BiOI/UiO-66 heterostructure via nanoplate-on-octahedron: A novel Pn heterojunction photocatalyst for efficient sulfadiazine elimination. Chem. Eng. J. 451, 138624 (2023).

Ahmadi, S., Quimbayo, J. M., Yaah, V. B. K., de Oliveira, S. B. & Ojala, S. A critical review on combining adsorption and photocatalysis in composite materials for pharmaceutical removal: pros and cons, scalability, TRL, and sustainability. Energy Nexus. 17, 100396. (2025).

Liu, X. et al. Anchoring ZnIn2S4 nanosheets on cross-like FeSe2 to construct photothermal-enhanced S-scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic H2 evolution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 673, 463–474 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Insights into the Formation of Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals during Photocatalytic Degradation Processes of Ceftriaxone Sodium by ZnO/ZnIn2S4314137618 (Chemosphere, 2023).

Fernández-Velayos, S., Menéndez, N., Herrasti, P. & Mazarío, E. Ofloxacin degradation over nanosized Fe3O4 catalyst viathermal activation of persulfate ions. Catalysts 13, 256 (2023).

Behnami, A., Aghayani, E., Benis, K. Z., Sattari, M. & Pourakbar, M. Comparing the efficacy of various methods for sulfate radical generation for antibiotics degradation in synthetic wastewater: degradation mechanism, kinetics study, and toxicity assessment. RSC Adv. 12, 14945–14956 (2022).

Malefane, M. E. et al. Triple S-scheme biobr@ LaNiO3/CuBi2O4/Bi2WO6 heterojunction with plasmonic bi-induced stability: deviation from quadruple S-scheme and mechanistic investigation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 7, 181 (2024).

Malefane, M. E. et al. Induced S-scheme CoMn-LDH/C-MgO for advanced oxidation of amoxicillin under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 480, 148250 (2024).

Guo, W. et al. Degradation of sulfadiazine in water by a UV/O 3 process: performance and degradation pathway. RSC Adv. 6, 57138–57143 (2016).

Yang, S. & Che, D. Degradation of aquatic sulfadiazine by Fe 0/persulfate: kinetics, mechanisms, and degradation pathway. RSC Adv. 7, 42233–42241 (2017).

Kou, J. et al. Selectivity enhancement in heterogeneous photocatalytic transformations. Chem. Rev. 117, 1445–1514 (2017).

Malefane, M. E., Mafa, P. J., Managa, M., Nkambule, T. T. I. & Kuvarega, A. T. Boosted persulfate activation using Ba2CoMnO5 and LDH/CaCO3 for amoxicillin degradation: a comparative study. Adv. Sustainable Syst. 9, 2400434 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute for Medical Research Development Grant No. 4021407 [Ethical code: IR.SIRUMS.REC.1402.034].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This research is a collaborative effort by a team of authors with expertise in various areas relevant to the investigation. Ali Azari and Rahim Aali were involved in visualization, writing, reviewing, editing, and supervision. Hossein Kamani and Kamyar Yaghmaeian were involved in conceptualization, methodology, software, and writing-reviewing and editing. Hasan Pasalari and Ahmad Reza Yari were involved in formal analysis, methodology, investigation, and writing original draft preparation. Hossein Azari and Nafiseh Sharifi contributed to investigation, writing original draft, formal analysis, data collection, and methodology. Mohsen Dowlati and Ali Azari was involved in investigation, software, and validation. Finally, Mahmood Yousefi and Ali Azari was involved in material preparation, data collection, and analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aali, R., Azari, H., Pasalari, H. et al. Enhanced sulfadiazine degradation through synergistic visible light assisted peroxymonosulfate activation using a magnetic Fe₃O₄-ZnIn₂S₄ catalyst. Sci Rep 15, 25013 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10973-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10973-4