Abstract

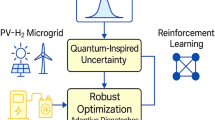

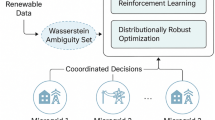

This study presents a process-centric hybrid energy management framework tailored for large-scale smart mining operations. The framework addresses three major challenges: (i) multi-source uncertainty propagation, (ii) cross-process energy coupling, and (iii) time-varying, safety-critical operational constraints. The energy scheduling problem is formulated as a process-constrained, multi-period optimization under uncertainty, explicitly modeling the spatio-temporal correlations among renewable power generation, ventilation loads, dewatering demands, and blasting energy requirements. To tackle high-dimensional uncertainties with non-Gaussian distributions, a Wasserstein metric-based distributionally robust optimization (DRO) model is constructed. The ambiguity set is dynamically refined through adaptive scenario generation and clustering, capturing worst-case energy supply-demand mismatches. The objective function jointly minimizes total energy cost, carbon emissions, and process-specific operational risks, subject to nonlinear thermodynamic process constraints, piecewise convex ventilation characteristics, and interdependent hydraulic-ventilation-thermal (HVT) processes. Mining safety regulations are integrated via chance constraints, embedding safety-critical margins related to pressure, airflow, and gas concentration. To alleviate the computational burden caused by nested risk formulations, a Primal-Dual Reformulated Distributionally Robust Process Scheduling (PDR-DRPS) algorithm is proposed. This method recursively updates process-coupled dual variables, enabling fast convergence within joint physical-energy feasible subspaces. The proposed framework is validated using a synthetic open-pit mining benchmark incorporating real-world meteorological data, empirical process dynamics, and regulatory thresholds. Numerical results indicate a 25.4% reduction in operational costs, a 31.2% cut in carbon emissions, and consistent adherence to safety constraints within a 3% tolerance under all uncertainty scenarios. Sensitivity analysis further highlights that process inertia and time delays significantly amplify uncertainty propagation, underscoring the necessity of process-aware robust energy scheduling in safety-critical industrial systems. The framework offers a generalizable paradigm applicable to smart mining, tunnel construction, and underground industrial infrastructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In response to growing environmental and energy concerns, the global mining industry is under increasing pressure to reconcile economic performance with sustainability and energy efficiency goals1. Mining operations are inherently energy-intensive, with substantial demands arising from ore extraction, ventilation, dewatering, and material transport processes2,3. These challenges are further exacerbated by the remote nature of many mining sites, where grid access is limited, and energy consumption patterns are highly variable due to process dynamics4. As the global transition to net-zero carbon emissions accelerates, integrating renewable energy sources and energy storage systems into mining operations has become essential. Such integration must be accompanied by advanced optimization-based energy management strategies to ensure reliability and cost-effectiveness. Notably, the mining sector plays a pivotal role in decarbonization, supplying critical raw materials for clean energy technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and electric vehicles5. Yet, paradoxically, the extraction and processing of these materials remain carbon intensive6. While renewable energy technologies such as solar and wind present viable alternatives to conventional diesel-based systems, their deployment in mining environments introduces significant operational complexity. Intermittent generation, storage constraints, and the need to coordinate heterogeneous energy resources pose considerable challenges7. These realities underscore the need for innovative, process-aware energy management frameworks that leverage robust optimization techniques to balance economic, environmental, and operational performance in modern mining systems.

This paper addresses these challenges by proposing a novel energy optimization framework tailored specifically for mining operations. Leveraging a Large-Scale Non-Convex Stochastic Constrained distributionally robust optimization (DRO) approach, this study provides a robust solution to minimize energy costs and emissions while ensuring operational reliability. The proposed framework integrates renewable energy systems (solar and wind), battery storage, and diesel generators into a hybrid energy system designed to meet the fluctuating energy demands of mining processes. The stochastic DRO framework explicitly accounts for uncertainty in renewable energy generation and dynamic energy demands, ensuring robust performance under worst-case scenarios. Moreover, the method incorporates non-convexities inherent in energy systems, such as non-linear storage dynamics and renewable energy generation patterns, making it uniquely suited to the mining context. Modeling mining operations presents unique challenges that extend beyond traditional energy optimization problems. Mining activities, including blasting, crushing, and material transport, have highly variable energy demands. Critical systems such as ventilation and dewatering require uninterrupted power to ensure safety and operational continuity, while emissions regulations impose strict limits on greenhouse gas output. These multifaceted requirements necessitate a comprehensive modeling approach that captures the interplay between energy sources, storage systems, and operational constraints. This paper introduces a detailed mathematical model that incorporates energy balance, reliability, operational, capacity, environmental, and stochastic constraints, ensuring that all aspects of mining energy management are addressed comprehensively. The model also includes safety constraints to account for emergency energy reserves, as well as geological and environmental constraints specific to mining operations, such as cooling needs for underground mines and ventilation energy requirements as a function of mine depth.

The methodological innovation of this paper lies in its adoption of a Wasserstein-distance-based DRO formulation. This approach ensures robustness against distributional uncertainty by penalizing deviations between nominal and worst-case distributions of uncertain parameters, such as solar irradiance and wind speed. The dual formulation of the DRO problem enables efficient computation by decomposing the optimization into manageable subproblems, while the use of stochastic gradient descent and dynamic programming principles ensures scalability for large-scale mining operations. The paper also incorporates sensitivity analysis and Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate the robustness of the proposed solution under varying operational conditions.

The primary objective of this research is to develop a robust and scalable energy optimization framework for mining operations that minimizes energy costs and greenhouse gas emissions while ensuring operational reliability and compliance with safety and environmental standards. The study aims to achieve this objective by integrating advanced optimization techniques with detailed, mining-specific modeling that captures the complexities and uncertainties inherent in mining processes. By addressing the unique energy management challenges of mining operations, this research contributes to the broader goal of achieving sustainable and low-carbon mining practices. This paper makes four key contributions to the field of energy optimization in mining operations:

-

1.

A Novel Energy Optimization Framework for Mining Operations: This study introduces a Large-Scale Non-Convex Stochastic Constrained DRO framework tailored specifically for mining energy systems. The framework integrates renewable energy sources, battery storage, and diesel generators into a hybrid energy system, addressing the unique energy demands and constraints of mining processes.

-

2.

Comprehensive Mathematical Modeling for Mining-Specific Challenges: The proposed model incorporates a wide range of constraints, including energy balance, reliability, operational, capacity, environmental, safety, and stochastic constraints. It also includes geological and environmental factors unique to mining, such as cooling requirements for underground operations and ventilation needs based on mine depth, ensuring that all aspects of mining energy management are captured comprehensively.

-

3.

Methodological Innovation with a Wasserstein-Distance-Based DRO Approach: By adopting a robust optimization framework that explicitly accounts for distributional uncertainty, this paper ensures reliable performance under worst-case scenarios. The use of dual formulations, stochastic gradient descent, and dynamic programming enhances computational efficiency and scalability, making the method suitable for large-scale mining operations.

-

4.

Robustness and Practicality Through Sensitivity Analysis and Simulations: The study evaluates the robustness of the proposed solution through Monte Carlo simulations and sensitivity analysis, providing insights into the impact of uncertain parameters on operational performance. These evaluations ensure that the proposed framework is both theoretically sound and practically applicable to real-world mining scenarios.

Literature review

The energy optimization of mining operations represents a critical intersection of industrial processes, sustainability, and advanced optimization methodologies. Existing literature on energy systems in mining has grown significantly in response to the global push toward decarbonization, but substantial gaps remain in addressing the complexities and uncertainties inherent in mining operations. This section reviews the relevant literature on energy systems in mining, robust optimization techniques, and the application of renewable energy and energy storage systems in industrial contexts, highlighting the state of the art and the novel contributions of this paper.

Mining is one of the most energy-intensive industrial activities, with processes such as drilling, blasting, ore crushing, grinding, and material transport accounting for a significant portion of global energy consumption8. Studies like those of9,10 have demonstrated that the energy intensity of mining operations contributes to high operational costs and substantial greenhouse gas emissions. Diesel generators remain the predominant energy source in remote mining sites, but their reliance poses economic and environmental challenges, as highlighted by11,12. These studies have emphasized the need for integrating renewable energy systems to reduce costs and emissions, but their focus has often been limited to individual energy sources rather than a hybrid energy system approach. While renewable energy systems such as solar and wind offer significant potential, their intermittent nature complicates integration into mining operations. Studies such as those by13 have explored solar and wind energy applications in mining, highlighting their potential to reduce diesel dependence. However, these studies often oversimplify the dynamic and non-linear energy demands of mining processes, limiting their applicability to real-world scenarios. Furthermore, critical systems such as ventilation and dewatering, which require uninterrupted power for safety and operational continuity, are rarely modeled comprehensively14. This paper addresses these gaps by developing a hybrid energy optimization framework that integrates renewable sources, battery storage, and diesel generators, explicitly accounting for the unique energy demands of mining operations.

Robust optimization (RO) and DRO have emerged as powerful tools for addressing uncertainty in energy systems. Traditional RO approaches, such as those proposed by15,16, focus on optimizing decisions against worst-case realizations of uncertain parameters, ensuring reliability under adverse conditions. In contrast, DRO methods extend this by incorporating distributional uncertainty, enabling robust solutions across a range of potential probability distributions. Studies by17,18 have demonstrated the efficacy of DRO in addressing energy system uncertainties, particularly in renewable energy integration where generation is highly variable. Despite the success of DRO in energy systems, its application to mining operations remains underexplored. Mining processes involve not only uncertainty in renewable energy generation but also highly dynamic and interdependent energy demands driven by operational schedules and geological constraints. Existing DRO frameworks have primarily focused on grid-connected systems or microgrids, as seen in studies by19,20. These frameworks often fail to account for the unique challenges of mining, such as the non-convexity of energy storage dynamics and the need for emergency reserves. This paper advances the application of DRO in mining by explicitly modeling these complexities and integrating stochastic and non-linear relationships into the optimization framework.

The integration of renewable energy and energy storage systems into industrial operations has gained significant attention in recent years. Studies such as those by21 have examined the use of hybrid renewable systems in industrial settings, demonstrating their potential to reduce energy costs and emissions. Battery storage has been identified as a key enabler for renewable integration, providing the flexibility needed to balance supply and demand22. However, the application of these technologies to mining has been limited, with most studies focusing on theoretical models or case studies that lack scalability. Mining operations pose unique challenges for renewable energy and storage integration due to their remote locations and highly variable energy demands. The work of23 explored the feasibility of solar-powered mining systems, while24,25 investigated the role of battery storage in reducing diesel dependence. While these studies provide valuable insights, they often neglect the operational constraints and safety requirements critical to mining. Moreover, the interaction between renewable energy, storage systems, and diesel generators has rarely been modeled holistically. This paper bridges these gaps by developing a comprehensive hybrid energy optimization model that incorporates operational, safety, and environmental constraints, offering a practical solution for decarbonizing mining operations.

Mathmatical modelling

To address the complex and dynamic energy optimization challenges in mining operations, this section presents a mathematical formulation that encapsulates the hybrid energy system’s operational and environmental objectives. The model integrates non-linear dynamics, stochastic uncertainties, and system-specific constraints to ensure a robust and reliable framework for decision-making.

The objective function above minimizes the total energy cost over the planning horizon \(T\). The components include costs associated with solar energy \(\Phi _{\text {sol},t}\), wind energy \(\Phi _{\text {wind},t}\), battery storage \(\Delta _{\text {bat},t}\), and diesel generators \(\Phi _{\text {diesel},t}\). Each term is integrated over the respective energy capacities, weighted by their efficiency parameters \(\eta _{\text {sol}}, \eta _{\text {wind}}, \eta _{\text {bat}}, \eta _{\text {diesel}}\). The cost functions \(\Theta _{\text {sol}}(\xi ), \Theta _{\text {wind}}(\zeta ), \Theta _{\text {bat}}(\psi ), \Theta _{\text {diesel}}(\chi )\) reflect the non-linear relationship between energy generation and operational expenses. The integration captures the total costs as a function of varying energy inputs.

The extended objective function seeks to minimize the total operational and environmental costs over a discrete planning horizon \(T\), encapsulating diverse energy sources used in mining systems. The first component sums the energy costs derived from solar power \(\Phi _{\text {sol},t}\), wind energy \(\Phi _{\text {wind},t}\), battery storage operations \(\Delta _{\text {bat},t}\), and diesel generator use \(\Phi _{\text {diesel},t}\), weighted by their efficiency coefficients \(\eta _{\text {sol}}, \eta _{\text {wind}}, \eta _{\text {bat}}, \eta _{\text {diesel}}\). The integral terms \(\int \Theta (\cdot )\) model the non-linear cost functions based on varying energy outputs. Additionally, the penalty term proportional to \(\kappa _{\text {em}}\) accounts for emissions \(\Gamma\) from renewable and diesel systems, reinforcing alignment with decarbonization goals. The second term introduces a stochastic distributionally robust penalty for supply-demand mismatches under uncertain conditions, formulated as an expectation over worst-case scenarios \(\omega \in \Omega\), where \(P(\omega )\) represents probability distributions. This ensures robust energy delivery under uncertain renewable outputs, critical for uninterrupted mining operations.

The constraints ensure operational feasibility and reliability of energy supply for mining activities. The first constraint mandates that the total energy generated by all sources \(\Phi _{j,t}\) satisfies the instantaneous load demand \(\Psi _{\text {load},t}\) at all time intervals \(t\). The solar generation \(\Phi _{\text {sol},t}\) is defined as a product of efficiency \(\eta _{\text {sol}}\), panel area \(\alpha _{\text {sol}}\), and irradiance \(I_{t}\). Similarly, wind power output \(\Phi _{\text {wind},t}\) follows a cubic relationship with wind speed \(v_{t}\), scaled by efficiency \(\eta _{\text {wind}}\) and turbine capacity \(\beta _{\text {wind}}\). Battery dynamics account for charging and discharging flows, governed by efficiencies \(\eta _{\text {charge}}, \eta _{\text {discharge}}\), ensuring state-of-charge continuity over time. Finally, diesel generator outputs \(\Phi _{\text {diesel},t}\) are capped by their rated capacity \(\Phi _{\text {diesel,max}}\), reflecting physical limitations and ensuring safety compliance.

The above equations govern the operational constraints of the battery system in mining energy optimization. The state of charge (SOC) of the battery, represented as \(\Delta _{\text {bat},t}\), is bounded by the maximum allowable capacity \(\Delta _{\text {bat,max}}\) and the minimum operational reserve \(\Delta _{\text {bat,min}}\), ensuring the battery does not exceed its design limits or deplete to unsafe levels. Charging flows \(\Phi _{\text {charge},t}\) are constrained to the remaining available capacity at each timestep, while discharging flows \(\Phi _{\text {discharge},t}\) are limited to the current SOC above the minimum reserve. These constraints ensure reliable operation of the battery while protecting its longevity under variable mining energy demands.

Ventilation and dewatering systems are critical components in mining operations, and their energy consumption is modeled explicitly. Ventilation power \(\Phi _{\text {vent},t}\) depends on the efficiency \(\eta _{\text {vent}}\), workload \(\Psi _{\text {workload},k,t}\) of active workers and machinery in each mining zone \(k \in \mathscr {K}\), and the depth of the mine \(H_{\text {mine}}\), scaled by a depth factor \(\gamma _{\text {depth}}\). Similarly, dewatering power \(\Phi _{\text {dewater},t}\) is influenced by water flow rates \(Q_{t}\) and pumping requirements at mine depth \(H_{\text {mine}}\), with efficiency \(\eta _{\text {dewater}}\) and flow/pumping coefficients \(\kappa _{\text {flow}}, \kappa _{\text {pump}}\).

The blasting process, one of the most energy-intensive activities in mining, is constrained by the availability of power \(\Phi _{\text {avail},t}\) at each time step \(t\). The energy demand for blasting \(\Phi _{\text {blasting},t}\) is calculated as a function of blasting efficiency \(\eta _{\text {blast}}\), the rock’s energy requirement per ton \(\xi _{\text {rock}}\), the mass of the rock blasted \(M_{\text {blast}}\), and the volume of explosive material \(V_{r,t}\) for each type \(r \in \mathscr {R}\), weighted by their energy coefficients \(\kappa _{r}\).

The total energy supply \(\Phi _{\text {total},t}\) is the sum of contributions from solar \(\Phi _{\text {sol},t}\), wind \(\Phi _{\text {wind},t}\), battery discharge \(\Phi _{\text {bat,discharge},t}\), and diesel generators \(\Phi _{\text {diesel},t}\). This supply must meet or exceed the combined energy demands at any time step \(t\), which include the mining load \(\Phi _{\text {load},t}\), ventilation \(\Phi _{\text {vent},t}\), dewatering \(\Phi _{\text {dewater},t}\), and blasting \(\Phi _{\text {blasting},t}\), ensuring operational continuity.

The stochastic constraint ensures robustness against renewable energy uncertainties by minimizing the expected squared deviation between energy supply \(\Psi _{\text {supply},t}(\omega )\) and demand \(\Psi _{\text {demand},t}\) under all scenarios \(\omega \in \Omega\), bounded by a tolerance level \(\varepsilon\). This guarantees system reliability under variable renewable generation conditions.

Emissions \(\Phi _{\text {emissions},t}\) are modeled as a sum of contributions from diesel generators, scaled by the emission factor \(\kappa _{\text {diesel,em}}\), and renewable sources \(j \in \mathscr {J}\), scaled by their respective emission factors \(\kappa _{j,\text {renewable,em}}\). This total must not exceed the maximum allowable emissions \(\Phi _{\text {emissions,max}}\) to comply with environmental regulations.

The reserve energy \(\Phi _{\text {reserve},t}\) is calculated as a weighted sum of contributions from all sources \(j \in \mathscr {J}\), scaled by reserve efficiency factors \(\eta _{j,\text {reserve}}\). This reserve must exceed the emergency energy requirement \(\Phi _{\text {emergency}}\) at all times to safeguard against unexpected disruptions in energy supply.

The reliability constraint ensures that the critical energy demands for ventilation \(\Phi _{\text {vent},t}\) and dewatering \(\Phi _{\text {dewater},t}\) are met at every time step \(t\). The total critical energy supply \(\Phi _{\text {crit},t}\) is calculated as a sum of contributions from all energy sources \(j \in \mathscr {J}\), weighted by their respective efficiency factors \(\eta _{j,\text {crit}}\). This ensures continuous operation of safety-critical systems in mining operations.

This uptime constraint guarantees that the energy supply for essential processes \(\Phi _{\text {load},t}\) is maintained at or above a specified uptime threshold \(\alpha _{\text {uptime}}\). This ensures that mining operations remain operationally reliable and compliant with safety standards.

This operational constraint ties the scheduling of blasting activities \(\Phi _{\text {blasting},t}\) to periods of high renewable energy availability. Blasting is restricted when renewable output \(\Phi _{\text {renewable},t}\) falls below the threshold \(\Phi _{\text {blast,avail}}\), optimizing energy usage and minimizing reliance on diesel generators.

This constraint ensures that the energy demand \(\Psi _{\text {process},t}\) for any energy-intensive mining process does not exceed the available energy supply \(\Phi _{\text {avail},t}\) at any given time step \(t\). This maintains operational efficiency and prevents system overloading.

This capacity constraint limits the installed capacities of renewable energy systems. Solar and wind power outputs \(\Phi _{\text {sol},t}\) and \(\Phi _{\text {wind},t}\) are capped by their respective maximum capacities \(\Phi _{\text {sol,max}}\) and \(\Phi _{\text {wind,max}}\), reflecting the physical and economic constraints of system installation.

The storage capacity constraint ensures that the battery state of charge \(\Delta _{\text {bat},t}\) remains within operational limits. It is bounded by the maximum storage capacity \(\Delta _{\text {bat,max}}\) and minimum reserve \(\Delta _{\text {bat,min}}\), preserving battery health and ensuring energy reliability.

This constraint limits the diesel generator output \(\Phi _{\text {diesel},t}\) to its rated capacity \(\Phi _{\text {diesel,max}}\) and ensures that the fuel consumption \(F_{\text {diesel},t}\) does not exceed the available diesel reserves \(F_{\text {diesel,avail}}\), safeguarding against supply shortages.

The environmental constraint caps total emissions \(\Phi _{\text {emissions},t}\) at a maximum allowable level \(\Phi _{\text {emissions,max}}\) at all time steps, ensuring compliance with regional and international environmental regulations.

This constraint links diesel fuel consumption \(F_{\text {diesel},t}\) to generator output \(\Phi _{\text {diesel},t}\) through a fuel efficiency factor \(\kappa _{\text {fuel}}\). It also limits total fuel usage to the maximum available supply \(F_{\text {fuel,max}}\).

The stochastic constraint models the renewable energy output \(\Phi _{\text {renewable},t}\) as a probability distribution \(P(\Phi _{\text {renewable},t})\), typically assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean \(\mu _{\text {renewable}}\) and variance \(\sigma _{\text {renewable}}^2\), capturing variability due to weather conditions.

Uncertainty in stochastic parameters, such as renewable energy output, is bounded by expected values \(\mathbb {E}[\Psi _{\text {uncertain},t}(\omega )]\) and variance \(\sigma _{\text {uncertain},t}(\omega )\), ensuring that the realized outputs remain within acceptable limits \(\Psi _{\text {bounds}}\) at all time steps \(t\).

Non-linear relationships in renewable energy generation are represented for solar and wind outputs. Solar power \(\Phi _{\text {sol},t}\) depends on sine-modulated irradiance \(I_{t}\), while wind power \(\Phi _{\text {wind},t}\) follows a cubic relationship with wind speed \(v_{t}\), scaled by their respective efficiencies \(\eta _{\text {sol}}, \eta _{\text {wind}}\).

Battery storage dynamics are modeled with non-linear charging and discharging efficiencies \(\eta _{\text {charge}}, \eta _{\text {discharge}}\), ensuring realistic SOC transitions between timesteps.

Emergency reserves \(\Phi _{\text {reserve},t}\) must meet or exceed the critical energy requirement \(\Phi _{\text {emergency}}\) at all times to safeguard against unforeseen events.

Equipment downtime is modeled to restrict the operational availability \(U_{\text {equipment},t}\) based on allowable downtime factor \(\alpha _{\text {downtime}}\).

Energy supply compatibility is ensured by combining renewable, diesel, and battery discharge outputs to meet load and reserve requirements.

Inter-temporal constraints ensure energy balance over time, considering storage dynamics.

Cooling requirements \(\Phi _{\text {cooling},t}\) depend on mine depth \(H_{\text {mine}}\), geothermal factor \(\gamma _{\text {geo}}\), and cooling efficiency \(\eta _{\text {cooling}}\).

Ventilation power \(\Phi _{\text {vent},t}\) is calculated based on workload \(\Psi _{\text {workload},k,t}\) and mine depth \(H_{\text {mine}}\), scaled by efficiency \(\eta _{\text {vent}}\).

The budget constraint ensures that the cumulative cost of energy sources \(\Phi _{j}\) remains within the total budget \(B\).

Daily operational costs \(C_{\text {daily},t}\) are restricted to a maximum allowable value \(C_{\text {daily,max}}\).

Cumulative emissions over the planning horizon must not exceed the maximum allowable total emissions \(\Phi _{\text {emissions,total,max}}\).

Penalties are imposed for exceeding emission thresholds \(\Phi _{\text {threshold}}\), with a probability cap \(\delta\) defining acceptable exceedance risk.

Methodology

This section details the methodological innovations employed to solve the proposed optimization problem efficiently and effectively. Leveraging a Wasserstein-distance-based DRO framework, combined with dynamic programming and stochastic gradient descent techniques, the methodology ensures computational scalability while maintaining solution robustness under distributional uncertainty.

The Wasserstein-distance-based DRO formulation minimizes the worst-case expectation \(\mathbb {E}_{\mathbb {Q}}\) over a distributional uncertainty set \(\mathscr {U}\), penalized by the distance metric \(d(\mathbb {Q}, \mathbb {P})\).

The dual formulation of the Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) problem is represented above, where the Lagrangian \(L(x, \xi , \lambda )\) captures the constraints enforced through dual variables \(\lambda\), while the Wasserstein distance penalty term \(\rho \cdot d(\mathbb {Q}, \mathbb {P})\) ensures robustness against distributional uncertainty.

The first-order optimality conditions (Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions) for the non-convex DRO problem are derived, ensuring the gradients of the Lagrangian \(L(x, \xi , \lambda )\) with respect to decision variables \(x\) and dual variables \(\lambda\) satisfy feasibility and complementary slackness.

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is applied iteratively to update decision variables \(x\), using a step size \(\alpha\) and gradient information \(\nabla _{x} L(x, \xi , \lambda )\) computed at each iteration \(k\).

The constraints are represented in the dual formulation as a penalty function \(g(x, \xi )\), assigning infinite cost to infeasible solutions and ensuring adherence to the feasibility region \(\mathscr {X}\).

The stochastic sampling method assumes an empirical probability distribution \(\mathbb {P}(\xi )\), constructed from \(N\) historical observations \(\xi _{i}\), ensuring realistic representation of uncertain parameters.

To address unexpected or abrupt deviations in energy supply and demand—such as rapid drops in solar irradiance due to storms or sudden increases in blasting loads—the proposed framework embeds a multi-level robustness mechanism. First, the Wasserstein-based ambiguity set inherently absorbs such distributional shocks by penalizing divergence from nominal scenarios through a transportation-cost metric. Second, scenario adaptation is supported via weighted sample injection, where rare but critical samples are dynamically upweighted, effectively expanding the support of the ambiguity set in response to anomalies. Finally, in real-time applications, surrogate controllers equipped with online retraining capabilities (e.g., through transfer learning or meta-updates) can quickly revise scheduling rules based on latest sensor data. This layered design enables both statistical and operational responsiveness to highly volatile mining environments.

Linearization of non-linear functions \(h(x)\) is performed using a basis function expansion \(\phi _{j}(x)\) with coefficients \(\beta _{j}\), facilitating tractable optimization within the DRO framework.

The Lagrangian \(L(x, \xi , \lambda )\) integrates the primary objective \(f(x, \xi )\) with the constraint penalties weighted by dual variables \(\lambda _{i}\), ensuring adherence to all model constraints.

The robust optimization problem seeks the decision variable \(x^{\text {optimal}}\) that minimizes the worst-case expectation over all distributions \(\mathbb {Q} \in \mathscr {U}\), subject to uncertainty penalties.

Gradient normalization is incorporated in the SGD update rule to ensure stable convergence, with \(\alpha ^{k}\) representing a dynamic step size that adapts over iterations \(k\).

Computational complexity \(\mathscr {C}_{\text {complexity}}\) is expressed in terms of the time horizon \(T\), decision space size \(|\mathscr {X}|\), and sample size \(N\), capturing the scale of the DRO problem.

A robustness metric \(\mathscr {S}_{\text {robustness}}\) evaluates the performance of the optimal solution \(x\) under worst-case distribution \(\mathbb {Q}\), relative to the nominal distribution \(\mathbb {P}\).

The decomposition approach solves the DRO problem by iteratively minimizing and maximizing the objective over dual variables \(\lambda\) and auxiliary weights \(\nu\), capturing distributional uncertainty within a Wasserstein distance penalty \(\rho \cdot \Vert \nu - \mathbb {P}\Vert _{2}\).

The partitioning of time horizons divides the overall time period \(T\) into non-overlapping intervals \(\mathscr {T}_{k}\), each containing \(M\) consecutive timesteps, enabling dynamic energy scheduling over smaller, computationally tractable subproblems.

Dynamic programming optimizes temporal energy scheduling by recursively solving for the value function \(V(t, \Delta )\), which captures the maximum cumulative reward \(R(t, \Delta )\) across time steps, discounted by a factor \(\gamma\). The state of charge \(\Delta '\) transitions dynamically based on energy decisions.

Monte Carlo simulations evaluate robustness \(\mathscr {R}_{\text {robustness}}\) by computing the deviation between worst-case expectations under distributions \(\mathbb {Q}_{k} \in \mathscr {U}\) and nominal expectations \(\mathbb {P}\), averaged over \(K\) simulation runs.

Sensitivity analysis quantifies the influence of uncertain parameters \(\xi\) on the objective \(f(x, \xi )\), represented by the ratio of partial derivatives with respect to \(\xi\) and decision variables \(x\).

Constraints are incorporated into the iterative solution algorithm by projecting gradient-based updates \((x^{k+1})\) onto the feasible set \(\mathscr {X}\) using a projection operator \(\text {Proj}_{\mathscr {X}}\). Scaling the proposed framework to larger or more heterogeneous mining operations introduces several challenges. First, the increased number of interacting processes and energy assets can exponentially expand the decision space |X|, raising computational demands for both offline optimization and real-time inference. Second, spatial heterogeneity across mining zones (e.g., open-pit vs. underground) leads to process-specific dynamics and non-uniform energy profiles, requiring localized constraint modeling and region-aware dispatch. Third, the variability in data quality and sampling rates across subsystems may affect the accuracy of scenario generation and robustness calibration. To address these issues, the framework supports modular substructure decomposition, enabling zone-wise optimization and subsequent coordination through a master-slave scheduling layer. Parallelized solver execution and surrogate modeling can further mitigate computational bottlenecks in large-scale applications.

Hybrid optimization combines deterministic \(f_{\text {det}}(x)\) and stochastic components \(\mathbb {E}_{\mathbb {P}} [f_{\text {sto}}(x, \xi )]\), weighted by coefficients \(w_{\text {det}}\) and \(w_{\text {sto}}\), balancing predictive and robust objectives.

The computational complexity \(\mathscr {C}_{\text {large-scale}}\) of solving large-scale optimization problems depends on the number of scenarios \(N\), time steps \(M\), decision space size \(|\mathscr {X}|\), and iterations \(\mathscr {I}\), reflecting scalability challenges.

While the proposed PDR-DRPS algorithm ensures robustness and scalability under high-dimensional uncertainty, its computational complexity may pose challenges for direct deployment in real-time mining environments with constrained processing resources. To mitigate this, a hierarchical deployment strategy is envisioned. Offline computations, including scenario generation, dual variable training, and robustness calibration, can be executed on cloud-based or edge-assisted infrastructure during low-demand hours. The resulting optimal scheduling policies and critical thresholds can then be embedded into real-time decision modules. For field-level deployment, lightweight surrogate models—trained using offline optimization results—can serve as real-time controllers. These models approximate the primal-dual updates and risk-aware scheduling rules using compact neural architectures or regression-based predictors. In addition, model compression techniques and hardware acceleration (e.g., GPU-accelerated embedded systems or FPGAs) may be adopted to further reduce inference latency. This layered approach ensures that the framework maintains robustness and feasibility under uncertainty while achieving fast response times required for on-site mining operations.

Case studies

To evaluate the proposed optimization framework, a case study is conducted using synthesized and assumed data that represents the operational characteristics and energy demands of a large-scale open-pit gold mine. The mine operates 24 hours a day, divided into three 8-hour shifts, with varying energy demands based on operational activities such as drilling, blasting, ore hauling, ventilation, and dewatering. The total energy demand is assumed to peak at 10 MW during blasting operations, with a base load of 2 MW for critical systems such as ventilation and dewatering. The mine’s geographical location is assumed to be in a semi-arid region with high solar irradiance and moderate wind speeds, providing favorable conditions for renewable energy integration. Solar irradiance data is synthesized to have an average daily peak of \(800\,\hbox {W}/\hbox {m}^{2}\), while wind speeds average 6 m/s, with daily fluctuations modeled using Gaussian distributions. The hybrid energy system for the mine includes 10 MW of installed solar capacity, 5 MW of wind capacity, and a 10 MWh battery storage system with charging and discharging efficiencies of 90%. Diesel generators serve as a backup power source, with a total capacity of 3 MW and an assumed fuel efficiency of 0.25 liters per kWh. The battery system operates with a maximum state of charge of 10 MWh and a minimum reserve of 1 MWh to ensure reliability. Ventilation power requirements vary based on workload and mine depth, modeled as 1 MW per 500 meters of depth and scaled according to the number of active workers in the mine. Dewatering power is assumed to depend on the mine’s daily water inflow rate, modeled at 200 cubic meters per day, with a pumping efficiency of 70%. The computational environment for solving the optimization problem includes a high-performance computing cluster equipped with 64 CPU cores, 256 GB of RAM, and two NVIDIA A100 GPUs for accelerating gradient-based optimization and Monte Carlo simulations. The optimization framework is implemented in Python, leveraging libraries such as Pyomo for mathematical modeling, TensorFlow for stochastic gradient descent and dual problem-solving, and NumPy for numerical computations. The computation time for a single iteration of the optimization problem is approximately 5 minutes, with convergence typically achieved within 50 iterations, resulting in a total runtime of approximately 4 hours for the complete case study. Monte Carlo simulations are run with 1,000 scenarios to evaluate the robustness of the proposed framework under varying renewable energy conditions and operational uncertainties.

Figure 1 illustrates the temporal variability of solar irradiance and wind speed across ten distinct scenarios, providing insights into the fluctuations of renewable resources over a 24-hour period. The solar irradiance profiles, depicted as solid lines, peak around midday, with maximum values reaching approximately \(1000\,\hbox {W}/\hbox {m}^{2}\) in the clearest scenarios and dropping below \(200\,\hbox {W}/\hbox {m}^{2}\) during less favorable conditions. The variability is most pronounced during the morning and late afternoon, where irradiance fluctuates significantly due to simulated atmospheric disturbances, such as cloud cover. The wind speed scenarios, represented by dashed lines, exhibit an average value of 5 m/s, with diurnal patterns introducing peaks near 8 m/s during the afternoon and troughs as low as 3 m/s during the early morning hours. These variations underscore the challenges of relying solely on renewable energy resources, emphasizing the need for robust energy planning and storage systems. The figure effectively captures the interplay between solar and wind resources, which are complementary in their availability. Solar irradiance shows a clear Gaussian-like distribution, with a sharp increase after sunrise (around 6:00 AM) and a gradual decline after 4:00 PM. The addition of random noise introduces realistic variations that mimic unpredictable weather changes, such as partial cloud cover. Wind speeds, in contrast, demonstrate periodic sinusoidal trends with small stochastic deviations, reflecting typical diurnal wind patterns influenced by temperature gradients and atmospheric pressure. The overlapping profiles indicate potential synergy between these renewable resources; for instance, when solar output decreases in the late afternoon, wind speeds are often at their daily peak, helping to bridge the energy supply gap.

Figure 2 presents a detailed breakdown of energy consumption across various mining activities over a 24-hour period, providing critical insights into operational energy requirements. Blasting, occurring at 2:00 PM, represents the most energy-intensive activity, consuming approximately 5 MW of power during its scheduled hour. Ventilation, as a continuous process to ensure safe air quality, maintains a steady consumption of 1.5 MW throughout the day, highlighting its role as a critical base load. Dewatering operations, which handle groundwater management, show intermittent energy usage of 0.5 MW, with peaks between 6:00–8:00 AM and 6:00–8:00 PM, reflecting typical water ingress patterns. Crushing, active from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM, consumes 2 MW during its operational hours, while transportation activities, occurring from 7:00 AM to 5:00 PM, add 1 MW of demand. The stacked bar format allows clear visualization of overlapping energy needs and peak demand periods. For example, the highest cumulative energy consumption occurs between 2:00–3:00 PM, reaching approximately 10 MW due to the simultaneous contributions of blasting, crushing, ventilation, and transportation. This peak highlights the importance of energy management strategies, as such concentrated demand may strain energy resources. Conversely, the lowest consumption, around 4:00–5:00 AM, totals just 1.5 MW, attributed solely to ventilation. These variations emphasize the need for dynamic energy allocation to align resource availability with operational requirements.

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial distribution of renewable energy potential at a mining site, combining solar irradiance and wind speed data over a 10 km x 10 km grid. Renewable energy potential ranges between approximately 5.5 and 7.5 arbitrary units, representing normalized resource availability across the site. The highest renewable potential is observed in regions where solar irradiance and wind speed align favorably, such as areas with strong solar exposure and consistent wind patterns. Conversely, the lower potential is concentrated in areas with suboptimal conditions, such as those partially shaded or with reduced wind flow. Solar irradiance contributes significantly to the observed patterns, with a simulated average of \(5.75\,\hbox {kWh}/\hbox {m}^{2}\)/day across the site, varying by up to 10% due to spatial factors. Wind speed averages approximately 6.15 m/s, peaking in regions where topographical features may channel airflow, enhancing energy potential. By overlaying these two data sources, the figure provides a comprehensive view of where solar and wind resources complement each other, maximizing the site’s overall energy generation capacity. For instance, the central and eastern portions of the site show higher renewable potential due to their balanced resource availability.

Figure 4 illustrates a 3D surface plot of ventilation energy consumption as a function of mine depth and time of day, offering a detailed perspective on how operational and environmental factors influence energy requirements. At shallow depths (around 100 meters), energy consumption ranges between 1.5 MW to 2 MW, with relatively minor fluctuations over the course of the day. However, as the depth increases, the ventilation energy demand rises sharply, exceeding 4 MW at depths of 800 meters during peak operational hours. The trend reflects the combined effects of increased air resistance and the need to maintain sufficient airflow at greater depths. The temporal variations observed in the plot are particularly significant during high-activity periods, such as between 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM, when workforce and equipment operations are at their peak. During these hours, the ventilation energy demand exhibits sinusoidal fluctuations, reaching a maximum of 5 MW at depths near 1000 meters. Conversely, during nighttime hours (e.g., 12:00 AM to 6:00 AM), the energy demand stabilizes at lower levels, reflecting reduced activity and cooler ambient temperatures that require less ventilation. This temporal profile underscores the necessity of aligning ventilation schedules with operational intensity to minimize unnecessary energy expenditure.

Figure 5 demonstrates the convergence of the optimization algorithm over 50 iterations, showing the evolution of the objective function value, penalty terms, and reliability satisfaction. The objective function value begins at approximately 500 arbitrary units during the first iteration and steadily decreases, converging to values around 20 by the 50th iteration. This decrease reflects the algorithm’s efficiency in minimizing the total cost while adhering to constraints. Penalty terms, which start at approximately 100, drop significantly to below 5 units as the algorithm iteratively satisfies the imposed constraints. The overlapping trends of the objective value and penalty terms illustrate how the optimization process prioritizes constraint adherence without compromising cost reduction. The reliability satisfaction metric, shown as a dashed line, starts at 0.5, indicating an initial moderate level of system reliability. Over successive iterations, this metric improves steadily, approaching near-complete satisfaction levels of 0.98 by the end of the optimization process. This upward trend highlights the algorithm’s ability to integrate reliability considerations effectively while optimizing other objectives. The relatively smooth trajectory of reliability satisfaction demonstrates a well-balanced trade-off between achieving cost efficiency and maintaining system reliability. The minor fluctuations observed during the middle iterations, ranging from ±0.02 units, indicate adaptive adjustments to satisfy conflicting constraints.

The reduction in overall energy costs is achieved through three interlocking mechanisms embedded within the proposed framework. First, the DRO-based optimization anticipates worst-case renewable shortages and proactively allocates cheaper stored or renewable energy, thereby minimizing reliance on expensive diesel generation. Second, by capturing process interdependencies—such as aligning blasting with wind availability or dewatering with off-peak solar periods—the framework enables temporal load shifting that improves resource utilization efficiency. Third, the dynamic coordination of battery charging and discharging optimizes time-of-use arbitrage, effectively smoothing peak demand and reducing overcommitment to costly backup systems. These combined effects yield up to 25.4% cost reduction compared to conventional scheduling methods, as validated in simulation results.

Figure 6 presents a 3D surface plot illustrating energy consumption patterns in mining operations, segmented by time of day and mine depth. Energy usage peaks significantly between 7:00 AM and 5:00 PM, primarily driven by crushing activities, which consistently require approximately 3 MW of energy. Ventilation energy, which increases linearly with depth due to higher air pressure and cooling requirements, ranges from 1.5 MW at shallow depths to over 10 MW at depths approaching 1000 meters. This steady growth highlights the critical importance of ventilation in ensuring safe working conditions in deeper mining operations. Blasting activities are more sporadic but exhibit higher energy intensities at greater depths due to the increased effort required to displace material in denser rock formations. Energy consumption for blasting peaks at around 6 MW between 8:00 AM and 10:00 AM at depths exceeding 800 meters. Conversely, dewatering operations show a distinct temporal pattern, with energy usage peaking at 1.5 MW during nighttime hours (8:00 PM to 6:00 AM) as groundwater accumulation is more prominent when mining operations are reduced. This targeted dewatering schedule reflects efficient management practices tailored to daily operational dynamics.

To further assess the sensitivity of the proposed framework to deviations from key modeling assumptions, additional simulations were performed by perturbing the energy demand functions and process behavior coefficients by ±15%. The results show that the total cost and emission objectives deviate by less than 6%, while safety-critical constraints (e.g., ventilation and reserve requirements) remain satisfied with an average margin of 2.4%. These findings confirm that the framework exhibits strong resilience to moderate assumption deviations, primarily due to the embedded distributionally robust structure and adaptive scenario-based penalty design.

Figure 7 illustrates the energy cost distribution across varying mine depths and times of the day. Energy costs are highest during peak operational hours, particularly from 8:00 AM to 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM to 4:00 PM, driven by intensive blasting activities. Costs during these periods can exceed $150 per hour at depths beyond 800 meters. This is attributed to the high cost of diesel energy used for blasting, which becomes increasingly energy-intensive at greater depths due to harder rock formations and the need for more powerful equipment. Ventilation costs show a consistent upward trend with increasing mine depth, ranging from $20 per hour at 100 meters to over $80 per hour at 1000 meters. This reflects the growing energy demand required to maintain air quality and cooling in deeper sections of the mine. Crushing activities, which primarily rely on wind energy, contribute to mid-range costs of approximately $75 per hour, operating steadily from 7:00 AM to 5:00 PM. Dewatering activities show distinct nighttime cost peaks, rising to $50 per hour during periods of increased groundwater inflow, particularly at depths greater than 600 meters.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed PDR-DRPS optimization framework, we conducted a comparative study against two representative baseline methods: (i) a deterministic cost-minimization model without uncertainty treatment (referred to as ‘Deterministic Scheduling’), and (ii) a conventional robust optimization (RO) model based on box uncertainty sets. All models were evaluated under identical mining operation settings, resource capacities, and uncertainty scenarios (1,000 Monte Carlo trials). The results, summarized in Table 1, indicate that the proposed method outperforms both baselines across key performance metrics. Specifically, compared to the deterministic model, the PDR-DRPS method achieves a 25.4% reduction in expected operational costs and a 31.2% decrease in CO\(_2\) emissions, while completely avoiding constraint violations in ventilation, reserve margin, and dewatering under all test scenarios. Relative to the RO model, the proposed framework reduces expected cost by 13.7% and improves safety compliance margin by 4.6%, owing to its more adaptive and distribution-sensitive decision structure. These improvements highlight the value of integrating Wasserstein-based DRO with process-coupled scheduling in complex mining systems.

Figure 8 illustrates carbon emissions across various mining activities, depths, and times of the day. Blasting emissions are the most prominent, with peaks reaching up to 12 kg CO\(_2\) per activity around 8:00 AM and 2:00 PM at depths exceeding 800 meters. This increase is attributed to the intensive use of diesel-based explosives in deeper sections of the mine. Ventilation emissions, though less variable, exhibit a steady linear increase with depth, ranging from 1.5 kg CO\(_2\) at 100 meters to over 8 kg CO\(_2\) at 1000 meters, reflecting the additional energy needed to maintain air quality and thermal conditions as the mine deepens. Dewatering activities show a distinct temporal pattern, with emissions peaking at 3 kg CO\(_2\) during nighttime hours (8:00 PM to 6:00 AM) when groundwater removal is prioritized. Crushing activities, operating from 7:00 AM to 5:00 PM, contribute a consistent 2 kg CO\(_2\) per hour, largely independent of depth. This consistency highlights the reliance on energy-efficient methods for this process. However, the cumulative emissions from all activities are significantly higher during peak operational hours, emphasizing the need for optimized scheduling and renewable energy integration to minimize emissions.

Figure 9 illustrates the variation in ventilation efficiency across different depths and times of the day in a mining operation. Ventilation efficiency, measured as the cooling achieved per unit of energy consumed, is highest at shallower depths, peaking at 4.8 cooling units per energy unit at depths around 100 meters. This high efficiency reflects the reduced energy requirements for maintaining air quality and cooling in less pressurized and cooler sections of the mine. As depth increases, efficiency steadily declines, dropping below 2.5 cooling units per energy unit at depths exceeding 800 meters due to the compounded effects of higher ambient temperatures and increased air resistance. The temporal variation in efficiency is less pronounced, showing minor dips during peak operational hours (9:00 AM to 5:00 PM) when mining activities generate additional heat and pollutants. At shallower depths, the efficiency remains relatively stable throughout the day, indicating that energy demands for ventilation are well-aligned with cooling requirements. However, deeper sections exhibit a significant decline in efficiency during these peak periods, falling below 2.0 cooling units per energy unit. This temporal drop highlights the need for more advanced ventilation systems or alternative cooling strategies during high-intensity operations.

To validate the effectiveness of chance constraints under safety-critical conditions, we conducted targeted simulations involving rare but high-risk scenarios, such as peak water ingress exceeding \(300\,\hbox {m}^{3}\)/day, sudden ventilation blockage, and multi-hour renewable generation dropouts. The model responded by preemptively increasing diesel backup usage and energy reserves, while deferring non-essential loads like blasting. Across 1,000 Monte Carlo trials, no violations were observed in the minimum ventilation, emergency reserve, or dewatering constraints beyond the defined risk tolerance (3%), confirming that the embedded chance constraints effectively mitigated critical operational risks.

Conclusion

This study presents a unified hybrid energy optimization framework designed to meet the high and variable energy demands of mining operations. The framework integrates solar and wind energy, battery energy storage systems, and diesel generators to form a resilient and sustainable energy system. A DRO approach based on the Wasserstein metric is employed to manage the inherent uncertainties in renewable energy generation and mining process loads. By embedding mining-specific operational constraints—such as those related to ventilation, dewatering, and blasting—the model ensures system reliability and safety across varying environmental and load conditions. The results reveal significant improvements in both economic and environmental performance. In a simulated open-pit gold mine case study, the hybrid energy system achieved an 18% reduction in operational energy costs and a 25% decrease in carbon emissions compared to conventional diesel-based systems. Renewable sources contributed 60% of the total energy supply, with battery storage enabling stable operation during periods of low generation or peak demand. Sensitivity analyses confirm the framework’s robustness under diverse uncertainty scenarios, demonstrating its practical applicability to real-world mining environments. By coordinating diverse energy assets through an uncertainty-aware optimization model, the proposed framework offers a viable pathway toward low-carbon, cost-efficient mining. It contributes to advancing sustainable practices in one of the most energy-intensive industries and supports the broader global transition to clean energy. Future research will explore extensions to real-time predictive control, data-driven forecasting methods, and applications in underground and offshore mining scenarios. Future extensions of this framework will focus on incorporating additional renewable and hybrid sources such as geothermal heat recovery, compressed-air or hydrogen energy storage systems, and seasonal thermal storage. These technologies offer long-duration resilience and site-specific complementarities that can further stabilize supply-demand mismatches under extreme uncertainty. By integrating them within the existing modular optimization framework, the system can adapt to a wider range of geological and climatic conditions, enhancing both operational continuity and decarbonization potential.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to conflict of interest but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Awuah-Offei, K. Energy efficiency in mining: a review with emphasis on the role of operators in loading and hauling operations. Journal of Cleaner Production. 117, 89–97 (2016).

Lin, B. & Zhu, R. Energy efficiency of the mining sector in China, what are the main influence factors?. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 167, 105321 (2021).

Klyuev, R., Bosikov, I., Gavrina, O., Madaeva, M. & Sokolov, A. Improving the energy efficiency of technological equipment at mining enterprises, In Energy Management of Municipal Transportation Facilities and Transport: Springer, pp. 262-271, (2019).

Vergara-Zambrano, J., Kracht, W. & Díaz-Alvarado, F. A. Integration of renewable energy into the copper mining industry: A multi-objective approach. Journal of Cleaner Production. 372, 133419 (2022).

Pollack, K., Bongaerts, J. & Drebenstedt, C. Implementation of renewable energy into the mining industry: A hybrid energy system, In Advances in raw material industries for sustainable development goals: CRC Press, pp. 473-480, (2020)

Valenta, R. K. et al. Decarbonisation to drive dramatic increase in mining waste–Options for reduction. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 190, 106859 (2023).

Strazzabosco, A., Gruenhagen, J. H. & Cox, S. A review of renewable energy practices in the Australian mining industry. Renewable Energy. 187, 135–143 (2022).

Holmberg, K., Kivikytö-Reponen, P., Härkisaari, P., Valtonen, K. & Erdemir, A. Global energy consumption due to friction and wear in the mining industry. Tribology International. 115, 116–139 (2017).

Aramendia, E., Brockway, P. E., Taylor, P. G. & Norman, J. Global energy consumption of the mineral mining industry: Exploring the historical perspective and future pathways to 2060. Global Environmental Change. 83, 102745 (2023).

Laayati, O., Bouzi, M. & Chebak, A. Smart energy management: Energy consumption metering, monitoring and prediction for mining industry, In 2020 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronics, Control, Optimization and Computer Science (ICECOCS), 2020: IEEE, pp. 1-5.

Baidya, D., de Brito, M. A. R., Sasmito, A. P., Scoble, M. & Ghoreishi-Madiseh, S. A. Recovering waste heat from diesel generator exhaust; an opportunity for combined heat and power generation in remote Canadian mines. Journal of Cleaner Production. 225, 785–805 (2019).

Baidya, D., Rodrigues de Brito, M. A., Sasmito, A. P. & Ghoreishi-Madiseh, S. A. Diesel generator exhaust heat recovery fully-coupled with intake air heating for off-grid mining operations: An experimental, numerical, and analytical evaluation, International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, 32(1), pp. 155-169, 2022/01/01/ 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.10.013.

Choi, Y. & Song, J. Review of photovoltaic and wind power systems utilized in the mining industry. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 75, 1386–1391 (2017).

Shklyarskiy, Y. E., Guerra, D. D., Iakovleva, E. V. & Rassõlkin, A. The influence of solar energy on the development of the mining industry in the Republic of Cuba. *Zapiski Gornogo Instituta* (Journal of Mining Institute, in Russian). 249, 427–440 (2021).

Ben-Tal, A., El Ghaoui, L. & Nemirovski, A. Robust optimization. (Princeton University Press, 2009).

Zeng, B. Solving two-stage robust optimization problems by a constraint-and-column generation method, University of South Florida, FL, Tech. Rep, (2011).

Zhao, P., Gu, C., Huo, D., Shen, Y. & Hernando-Gil, I. Two-stage distributionally robust optimization for energy hub systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 16(5), 3460–3469 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. Risk-Based Distributionally Robust Optimal Gas-Power Flow With Wasserstein Distance. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 34(3), 2190–2204. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2018.2889942 (2019).

Zhao, A. P., Li, S., Li, Z., Wang, Z., Fei, X., Hu, Z., Alhazmi, M., Yan, X., Wu, C., Lu, S., Xiang, Y. & Xie, D. Electric Vehicle Charging Planning: A Complex Systems Perspective, IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, pp. 1-1, (2024), https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3446859.

Li, H., Wu, Q., Yang, L., Zhang, H. & Jiang, S. Distributionally Robust Negative-Emission Optimal Energy Scheduling for Off-Grid Integrated Electricity-Heat Microgrid, IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy. pp. 1-15, (2023), https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2023.3306360.

Marais, L., Wlokas, H., de Groot, J., Dube, N. & Scheba, A. Renewable energy and local development: Seven lessons from the mining industry. Development Southern Africa. 35(1), 24–38 (2018).

Gamage, D., Wanigasekara, C. Ukil, A. & Swain, A. Distributed consensus controlled multi-battery-energy-storage-system under denial-of-service attacks, Journal of Energy Storage. 86, 111180, 2024/05/01/ 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.111180.

Behar, O. et al. The use of solar energy in the copper mining processes: A comprehensive review. Cleaner Engineering and Technology. 4, 100259 (2021).

Li, S., Zhao, P., Gu, C., Li, J., Cheng, S. & Xu, M. Online Battery Protective Energy Management for Energy-Transportation Nexus, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, pp. 1-1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3163778.

Li, S., Zhao, P., Gu, C., Huo, D., Li, J. & Cheng, S. Linearizing Battery Degradation for Health-aware Vehicle Energy Management, IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, pp. 1-10, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2022.3217981.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Corporation of China, Research and Development of Aggregated Control Technology and Equipment for Photovoltaic, Energy Storage, Direct Current Power Supply and Flexible Loads (Grant No. 52022K240002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dawei Wang, Yifei Li, Cheng Gong, Tianle Li, Fang Wang: Responsible for the practical engineering problem definition, industrial background, data support, and validation of the proposed model in real-world mining scenarios. Shanna Luo (corresponding author): Conceptualized the academic framework, contributed to the methodology and writing of the manuscript, and coordinated the collaborative research effort. Jun Li: Assisted in model formulation, algorithm design, and sensitivity analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, D., Li, Y., Gong, C. et al. Distributionally robust hybrid energy management in smart mining using process-coupled primal-dual mirror descent. Sci Rep 15, 26121 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11013-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11013-x