Abstract

Treatment for a cleft lip can result in significant functional and aesthetic changes to the nasolabial region. Although three-dimensional (3D) measurements are the gold standard for evaluating cleft surgery, most short- and long-term evaluations still rely on subjective assessment or the measurement of patient photographs. To our knowledge, this work establishes the first baseline and reference group for the nasolabial region in children aged 3 to 9 months without cleft lip or palate. This group can be used for future evaluations, such as those of surgical outcomes or NAM therapy, via 3D anthropometric measurement. Data was collected cross-sectionally from 25 children aged 3 to 9 months using a validated intraoral scanner (Trios 4, 3Shape). Scans were analysed according to 3D anthropometric criteria by metrically accurate measurements of distances, surface curves and angles using 3D inspection software (GOM Inspect, Co. Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Results are presented as reference database combined with a step-by-step guide on the measurement methodology. For easy application all data are additionally presented in the form of formulae in which clinical data can be inserted. Based on the data from healthy children, we propose a new classification of alar base types ranging from 1 to 3. Unlike conventional assessment methods, surface curves and other 3D anthropometric tools provide a highly accurate and objective quantification of the anatomy of the nasolabial region and thus serve as a foundation for future clinical research on cleft lip surgery. Alar base type classification may influence future surgical approaches to cleft lip surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The treatment of congenital deformities of the nasolabial region has far-reaching consequences for the future lives of our young patients. It should therefore be the goal of every cleft surgeon to provide the best possible treatment in order to create both function and aesthetics. Today, long after Millard’s work, the field of cleft surgery continues to change and improve, or as Millard himself once stated: ‘Semper investigans, nunquam perficiens. Always searching, never achieving (perfection)’1,2.

In order to progress towards the optimal outcome, it is essential to visualise and define it. To date, many studies have assessed the ‘where have we got to?’ by evaluating the outcomes of cleft lip surgery using various aesthetic scoring systems or symmetry assessments3,4,5,6,7. So far, Loo et al. are one of the very few to assess the ‘where exactly do we want to get to’ by describing the anthropometic morphology of the ‘normal Cupid’s bow’ in healthy young children8.

In today’s era of three-dimensional (3D) analysis techniques, it is essential that we have reference databases of these ‘normal’ anthropometics combined with appropriate and precise evaluation methods. These tools are indispensable in order to identify the optimal, or in other words the most unobtrusive, result that we are looking for, and to analyse the aspects in which we have not yet achieved it. This will provide the basis for further improving surgeons’ understanding and skills, and therefore the surgical outcomes. By establishing an objective and valid basis for comparison, it will also allow us to evaluate the surgical outcomes in detail, and to improve the surgical techniques in a very targeted way. It is important to note that this is only possible if the databases’ range corresponds to the age at which primary surgical intervention takes place. Available literature suggests that this procedure takes place between three and nine months after birth9,10. The present work therefore focuses on this timeframe.

A recent shift towards 3D assessment in cleft surgery has led to the use of different data acquisition tools, ranging from 3D photography to the extraoral use of intraoral scanners11,12,13,14,15,16. As part of the validation of a suitable measurement tool, our group has recently demonstrated the superiority of the extraoral application of a commercially available intraoral scanner (3Shape, Trios4 and 5) in terms of accuracy and applicability in mapping the nasolabial region12. The use of this high-precision instrument, which is now well established, provides the opportunity to apply a novel measurement method using previously unidentified measurement parameters that differ from those used in conventional anthropometry.

The EUROCLEFT and SCANDCLEFT studies, with their respective scoring scales, have already established global standards for the assessment of outcomes following surgical correction of cleft lip and palate (CLP) defects10,17. Although both studies highlight a glaring lack of evidence in orofacial cleft surgery, they do not yet make use of new 3D anthropometry within the scope of the respective possibilities. The recent works of Bugaighis et al. and Xu et al. uses 3D instruments for image acquisition. However, they are limited to the conventional measurement parameters established in two-dimensional anthropometry, such as direct distances and angles15,18.

As we stand on the verge of transitioning from 2D to 3D assessment in cleft surgery, the aim of this study is to establish a baseline and reference group for future evaluations. Additionally, an accurate and reproducible methodology is to be established for the 3D assessment of the nasolabial region in children aged 3 to 9 months, taking into account surface reflections, surface curves and perpendicular lengths. As part of the study of healthy children, a classification of alar base types will be presented.

Methods

Patient acquisition

An intraoral scanner, previously established and validated by our working group12was used to acquire the nasolabial region of 47 healthy children aged 3 to 9 months, who presented to the Division of Phoniatrics and Paediatric Audiology at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Erlangen University Hospital. Three members of the working group performed the scans, and the scanner was calibrated before each process. Scans that were distorted or otherwise corrupted by the childrens’s movements were excluded, leaving 25 patients who met the requirements for 3D anthropometric measurement for further analysis. The average time taken was 3 min per child, and all children with nasolabial or generalised cranial deformities were excluded. Of the 25 children included, 13 were male and 12 were female. The mean age was 4 months and 18 days with a minimum age of 3 months and a maximum age of 8 months and 30 days. Birth weight was recorded as another demographic parameter.

All parents were informed in detail about the study and gave their informed written and verbal consent. All children’s legal guardians gave informed consent for the publication of identifying information/images in an online open access publication. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg on May 6, 2022 under the application number 22-100-B and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measuring methods

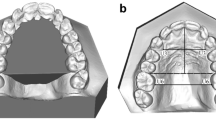

The measurement methodology was derived from the seminal work of Leslie G. Farkas, namely ‘Anthropometry of the head and face’, as well as from the contributions from Chong et al., Bughaigis et al. and Kesting et al.1,18,19,20. Subsequently, our working group modified this methodology to take advantage of the new possibilities offered by modern 3D anthropometry. This involved focusing on light reflections and incorporating surface curves and perpendicular lengths. The basis of all our 3D anthropometric measurements were 33 landmarks (Fig. 1a; Table 1), i.e. points on a surface that can be defined as constructed elements without a vector. The step-by-step guide, which is presented in the results section, was developed with the aim of defining their precise location and facilitating their placement for future work. Our final reference database consists of 32 distances (Fig. 1b), 33 surface curves (Fig. 1c), 2 angles (Fig. 1d) and 18 indices (Table 2).

(a) Overview of the 3D anthropometric landmarks of the nasolabial region. The 33 landmarks are placed on the virtual surface, taking into account anatomical structures, colour/texture and surface reflection. Detailed instructions on placing the landmarks can be found in Supplementaray Material 1 and 4. Corresponding number assignments (e.g. L1 - Nasion) can be found in the table in Supplementary Material 1. (b) Overwiew of the 3D anthropometric distances of the nasolabial region The 32 distances are measured as a direct length between two landmarks or as a perpendicular length between a previous measurement and a new landmark, as in the example of effective nasal length, dimple depth or right and left vermillion convexity. Corresponding number assignments (e.g. D1 - Nasal height) can be found in the table in Supplementary Material 1. (c) Overwiew of the 3D anthropometric surface curves of the nasolabial region. The 32 surface curves are positioned directly on the mesh. They can be set by raw placement using landmarks only, or by using intersection points. Detailed instructions on placing the surface curves and corresponding number assignments (e.g. S1 - Volumetric upper nasal height) can be found in Supplementaray Material 1. (d) Overwiew ot the 3D anthropometric angles of the nasolabial region The 2 angles consist of a 3-point angle and a bipartite angle. The vermillion angle is constructed as a 3-point angle, the collumellar angle as a 2-directional angle. Corresponding number assignments (e.g. A1 - Columellar angle) can be found in the table in Supplementary Material 1.

A distance is defined as the direct length between two points on a mesh or between a point on the mesh and a point on a previous measurement. A distance between a previous measurement and a new landmark can be constructed as a perpendicular length, as in the example of effective nasal length, dimple depth or right and left vermillion convexity (Fig. 1b).

Unlike normal curves, surface curves are positioned directly on the mesh (Fig. 1c). They are used to generate curvature curves that reflect the subject’s natural anatomy, while remaining independent of mesh/face rotation in space. This was confirmed by the authors through repetitive measurements using surface curves while manipulating the respective meshes in space, as well as by consulting the software developers. As a fundamental advance in the transition from conventional to 3D anthropometry, surface curves provide the ability to make new and more comprehensive statements about the facial morphology. They include the previously overlooked anatomical configurations between their respective start and end points. Taking into account the specific characteristics of each parameter and its prospective integration in future studies of cleft patients, we have determined for each surface curve, in particular, whether the intersection points are valid. If no intersection points are valid, only the start and end points of the surface curve should be set manually. Detailed instructions for each parameter are given in the Supplementary Material section.

3D anthropometric angles can be constructed in two ways: as three-point angles or as bipartite angles (Fig. 1d). Three-point angles are defined by three landmarks, one of which acts as the angle point. Bipartite angles can be constructed using elements containing a direction, a normal or a line (e.g. planes and lines) without them having to touch. In the context of our 3D anthropometric methodology, the vermillion angle is constructed as a 3-point angle between right and left cheilion and labrale superius, with the latter acting as the angle point. As a 2-directional angle, the columellar angle is formed by the line/distance between columellar median high point and subnasale, and the line/distance between right and left cheilion.

The indices function as constructed variables, facilitating the formation of new assertions regarding the interrelationship between the parameters and allowing a rapid assessment of the patient’s nasolabial conditions.

The data set was analysed according to 3D anthropometric criteria by metrically accurate measurements of distances, surface curves, angles and indices using 3D inspection software (GOM Inspect 2019 Hotfix 6, Rev. 125216, Build 2020-02-27, Co. Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Reliability tests were conducted using a sub-collective as a proxy for the entire collective to ensure reliable measurements. With an interval of two weeks intra-rater reliability was assessed for five children. Intra-rater reliability was calculated using the time points as different assessment occasions. The two-way intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for consistency and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) were calculated as measures of intra-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability is evaluated across all children for five parameters between three raters using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for two-way models employing an absolute agreement definition21,22. To ensure a high degree of reliability in the test, the working group mixed presumably ’easy’ and ‘hard’ parameters, as well as parameters relating to the nose and lip. Distances and surface curves of each kind were included. An ICC of < 0.40 is as considered poor agreement, values between 0.40 and 0.75 as substantial- and an ICC exceeding 0.75 as excellent23.

To improve the accuracy of the data, values were imputed based on clinically relevant information, such as the subject’s sex, age, and birth weight. This led to the predicted values presented in the Results section. Rationale for the imputation process: Providing the algorithm with high quality data from a limited number of samples, which have been measured with precision by an expert in the field, is a time-consuming process, but is preferable to measurements made by an expert under time pressure or by a non-expert for a large number of samples. In the present study, valid and precise data are employed to predict nonobserved values, rather than providing additional clinical data within the same time frame. This approach aims to minimize the impact of human error. All variables for which quantitative data were available were used to predict explicit missing values using the R package Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (mice 3.15.0) with predictive mean matching. Predictive mean matching was chosen because it has been shown to be effective in dealing with nonlinearity and outliers. An example of the observed and predicted parameters for 9 direct lengths and 7 surface curves is given in Table 3.:

The dataset used to impute missing values consisted of 25 children, with each subject having 85 distinct variables. The age range used for imputation was 3 to 8 months and 30 days, respectively. For the purposes of this analysis, each month was assumed to consist of 30 days. For the age range of 5 months (5/0–5/30 months/days) only one measurement point was available (5/22 months/days). The child was included in the dataset, but the age range of five months was not predicted. Similarly, for the age of seven months, there was no data available for a child and therefore the range was not predicted.

Parameters that are likely to be highly correlated, such as length measurements, were approximated together and grouped by individual. The rationale is once more straightforward:

It can be assumed that the “left lateral columella length” corresponds to the “right lateral columella length” of a healthy individual. Yet, for the purposes of this approximation, it is not necessary for this axiom to be met. However, if the aforementioned axiom is proven to be true, the information is utilised. It is important to note that the data are inherently interdependent, as some indices are calculated from the raw values of other variables. In addition, the values are naturally dependent on age, sex and birth weight. Consequently, if a raw value is missing, the index cannot be calculated, resulting in a dependent pattern of missing data. It should be noted that subsequently Little’s MCR Test was not computed.

Statistical analysis led to the presentation of the results in the form of growth curves and formulae according to Brons et al., Matthews et al. and Liang et al.24,25,26.

Results

Our final reference database consists of 32 distances (Fig. 1b), 32 surface curves (Fig. 1c), two angles (Fig. 1d) and 18 indices; representing the optimal morphological outcome as a control group for future research in cleft lip and palate surgery. Descriptive plots of all 84 datasets can be found in Supplementary Material 2, with observed values on the left and predicted values on the right. Age is given in months on the x-axis, and the specific value for each parameter is given on the y-axis in mm for distances and surface curves, in degrees for angles, and in numbers without dimension for indices. The red lines represent growth curves for female individuals and the blue lines for male individuals. To facilitate the application in both clinical and research settings, the comprehensive mathematical equation for each parameter is provided in Supplementary Material 3, with the equations presented for both male and female patients. In order to determine the optimal morphological result for a particular parameter, it is necessary to enter the current clinical value as age in months in the equation, or for simplification purposes in the column provided for the respective sex. We recommend using the predicted value equations.

For each child and each parameter, the intra-rater reliability was good/high or excellent/very high with a minimum value of ICC = 0.89 and r = .89. Stratified by type of parameter intra-rater reliability is lowest for angles and highest for surfaces (ICC = 0.99) with distances ranging in between (ICC = 0.90). For a tolerance of 1 mm, percentage agreement across all indices and children was 81.4%. Across variables assessed ICC for inter-rater reliability was 0.99 (p < .001) indicating nearly perfect absolute agreement between raters. The lowest ICC was found for the right vermillion length with an ICC of 0.73 (p < .001) indicating substantial agreement among raters. For a tolerance of 1 mm percentage agreement between raters was 43.9%. A possible cause of the lower ICC for some parameters, including right vermillion length, could be the challenging placement of the cheilion points.

Accurate positioning of the updated 3D anthropometric landmarks is required to ensure reproducible measurements. Therefore, in addition to a step-by-step tabular guide (Table 1 and Supplementary Material 1), we present a short video guide for 3D anthropometric landmark positioning (Supplementary Material 4).

As part of the establishment of our 3D anthropometric measurements and conclusive reference database, the new methodology allowed for a dedicated classification of alar and nasal shape. To facilitate future studies and to improve the individualised surgical approach to cleft lip and other nasolabial surgical procedures in general, we have identified the following three types of alar base:

-

Type I: mabR/mabL is more lateral than cR/cL.

-

Type II: mabR/mabL is more medial than cR/cL.

-

Type III: Direct transition from mabR/mabL to cbR/cbL.

Alar base type 1, the most common in our study population, is characterised by a wide and shallow labial nasal entrance and a continuously narrow columella. Alar base type 2 is characterised by a narrow and shallow labial nasal entrance and a columella that extends far cranially/anteriorly. In alar base type 3, a continuous ridge shields the labial nasal entrance from the rest of the upper lip. As shown in Fig. 2, alar base types not only influence the appearance of the alar, but also have a major impact on the overall appearance of the patient’s nose and can therefore be used to classify the nose in general.

In addition to the previous validation of metric accuracy of the intraoral scanner12we can now confirm its clinical applicability based on the long-term use in awake and sleeping children aged 3 to 9 months.

Discussion

To facilitate future studies in cleft surgery, we have identified the optimal morphological endpoint in the nasolabial region of healthy children aged 3 to 9 months. Our reference database will allow clinicians and research groups to compare the status quo or the morphological baseline of cleft patients before and after cleft lip repair with a healthy control group. Similar to the description of bone growth in healthy children by Liang et al., we present growth curves that now allow graphical and mathematical prediction of the expected value at a given age and sex25. In addition to previously established anthropometric parameters of the nasolabial region20our database takes into account recent advances in 3D anthropometry and includes surface curves, perpendicular lengths and the resulting comprehensive indices. To our knowledge, this is the first 3D anthropometric database of the nasolabial region in healthy children aged 3 to 9 months.

As mentioned above, 3D anthropometry is a highly accurate and advanced tool for evaluating the nasolabial region and has been shown to be superior to two-dimensional methods27,28. In line with this statement, recent literature indicates a paradigm shift in the evaluation of CLP surgery towards 3D evaluation13,15,18,29,30,31,32. To date, the majority of recent studies lack validation of the 3D (facial) scanner used13,15,18,30,31 and it is worth noting that some of the scanners used do not achieve the accuracy for craniofacial assessment touted by the industry12. As a 3D scanner for the assessment of cleft lip and palate must not only be highly accurate but also mobile in order to be used in clinical applications, a suitable device has recently been validated by our working group using a previously validated industrial scanner as a baseline12.

The use of this new data acquisition tool has opened up a host of new possibilities for 3D data processing and measurement. The mere ability to rotate the meshes in 3D space, together with a constant virtual light source, enables the accurate identification of previously difficult or indistinguishable anatomical structures through light reflection and shading. As light reflection and shading occur naturally at the edges of 3D structures in space and have been shown to be suitable for the perception and detection of 3D structures33,34,35,36the reflections appear to be well suited for the detection and separation of anatomical structures in the nasolabial region, such as the nose from the facial and labial tissues, the alae from the alar base, and the vermillion from the upper lip (see video and tables in the supplementary material). Furthermore, both our own experience and the current literature indicate that 3D anthropometry on coloured 3D surfaces seems to benefit 3D shape perception36. As most of the current articles on 3D anthropometry of the nasolabial region include measurements on monochrome surfaces32,37,38,39we recommend their implementation for further research in our field. It is worth mentioning, as a limiting factor, that although general data reproducibility was high to very high, some landmarks were slightly less reproducible than others with regard to inter-rater reliability. For instance, this was the case for parameters including the left and right cheilion as landmarks. These limitations could be overcome through future research and technological advances.

The novel approach of combining precise measuring instruments with the use of light reflections on coloured 3D surfaces now paves the way for a new and accurate method of measuring the outcome of cleft lip plasty.

Self-critical examination of one’s own accuracy and, above all, the reproducibility of data collection and processing is an important part of science and one that has been increasingly emphasised in recent years40,41. As we are now on the threshold of a paradigm shift towards 3D evaluation of cleft lip surgery with the implementation of all its technical and methodological possibilities, a unified and standardised approach within the discipline and between the working groups is of great importance. To this end, in addition to the reference database, we present step-by-step instructions for the consistent and reproducible placement of the updated anthropometric landmarks of the nasolabial region in text and video. Once the 33 landmarks have been created, the children (i.e. their scans) are measured using distances, surface curves, angles and indices. Once again, the use of 3D anthropometric methods offers new and far-reaching possibilities in all four areas of application mentioned, which go beyond their pure superiority in terms of precision and applicability.

The concept of distance has expanded beyond its traditional definition. It now encompasses more than just the linear measurement between two points (A and B). In modern spatial analysis, distance can also be quantified as the perpendicular length from a reference line to a point on a mesh or virtual surface. This technique, which to our knowledge has never been used in 3D nasolabial anthropometry, was used by our working group to determine the parameters of effective nasal length, dimple depth and right and left vermillion convexity.

When measuring the distance between point (A) and point (B), we disregard all information about the morphology in the form of natural convexities and concavities of the nasolabial region between the two points. Therefore, with the new capabilities of 3D anthropometry, we introduce the entity of surface curves, which follow the patient’s natural anatomy on the surface of the mesh, allowing it to be included in future evaluations and research.

Vermillionplasty is essential for adequate closure of the lip in unilateral cleft lip. Various techniques, with Noordhoff’s technique as a prominent forerunner, are currently being discussed with regard to their effect on vermillion convexity and, in the case of a suboptimal result, the loss of vermillion convexity1,42,43. Similarly, different techniques for bilateral cleft lip closure and their respective effects on the dimple morphology, which strongly influences the perception of a person’s attractiveness, have been the subject of much debate1,44,45,46,47. By quantifying the aforementioned distances, in particular dimple depth and left and right vermillion convexity, and adding surface curves, in this case the volumetric philtrum and vermillion length, as a new entity, we allow for profound and far-reaching conclusions to be drawn in future studies on the impact of different techniques in cleft lip surgery.

The pursuit of reproducible data collection and processing should go beyond the implementation of accurate and precise measuring methods. It is also essential to use a reliable statistical approach. Inclusion of missing data is used in several research areas where resources such as expertise, cost or readily available samples are scarce48,49. As long as the prediction model does not become too complex (at present), it has been shown that clinical data can be imputed reliably. For example, using data from 13 common laboratory tests and deliberately removing known information, 12 international teams were able to correctly estimate the missing information using probabilistic algorithms50. Clinical research needs to revalue missing values not as a genuine problem of a dataset, but as a challenge for mathematical modelling given the probabilistic and Bayesian algorithms available. Simply treating missing information as not present can lead to more severe artefacts in statistical analysis (e.g. assuming non-normality where data are actually normally distributed, up-weighting of actually random occurrences, which enlarges the confidence interval) than treating them51.

In our case, the benefit of imputation can be demonstrated by examining, for example the length of the right lateral columella (Fig. 3). The observed information leads the equation to assume a decrease in males, based on the large confidence interval between four and six months. However, the multiple chained regression equations for the predicted values indicates growth, thereby reducing the size of the confidence interval and providing information on a more fine-grained y-axis.

Observed and predicted values based on age, sex and weight for right lateral columnella length. All values are given in months and mm. The observed information leads the equation to assume a decrease in males, based on the large confidence interval between four and six months. However, the multiple chained regression equations for the predicted values indicates growth, thereby reducing the size of the confidence interval and providing information on a more fine-grained y-axis. Y-axis shows distance (mm). X-axis shows age (months).

The morphology of the nose, in particular the nostrils and their attachment point to the upper lip and the aforementioned columella, has a major influence on the overall appearance of an individual. Leslie G. Farkas has previously classified alar base configurations based on visually assessed criteria such as ‘short curved’ and ‘full curved’20. Despite the new 3D anthropometric capabilities, modern classifications are limited to pathologies and different treatment methods without describing the optimal morphological endpoint52,53,54,55. We therefore propose a simple classification of alar base types based on the 3D anthropometric landmarks cR/cL, cbR/cbL and mabR/mabL and their spatial relationship (Fig. 2). The potential for a detailed and consistent characterisation of alar base types now allows them to be incorporated into surgical procedures for the treatment of cleft lip. This can be achieved by considering the healthy side of the nose in unilateral clefts, or by considering the alar base types of close relatives. It should be noted, however, that further work on the inheritance of alar base types is needed to make accurate predictions based on close relatives.

Despite the high drop-out rate as a limiting factor of the study, it seems important to lay an early foundation in the form of reference databases on the nasolabial region of healthy children aged 3–9 months, thus anticipating technical advances in clinical 3D anthropometry. By minimising the time required per scan, intraoral scanners may become more feasible for awake and active children in the future. The use of smartphone-based scans also offers promising approaches, despite losses in metric accuracy56,57,58.

Good coverage rates and confidence interval widths can be achieved with small samples when suitable donor cases are available for imputation. The suitability of donor cases is inevitably linked to the (clinical) population of interest, addressing the underrepresentation of different ethnic groups. Although children of Asian (n = 2), Arab (n = 4) and African (n = 1) ethnicity were included to represent the average Central European patient population, there is no specific ethnic analysis of the optimal morphological endpoint. Given the small sample size and high exclusion rate despite precise measurement methodology, this should be the subject of future studies. The generation of ethnicity-specific databases, and the resulting potential to improve the treatment of nasolabial defects for individual patients, represents a challenging yet promising area of research.

Conclusions

By defining the optimal morphological endpoint, we have successfully established a basis for future 3D anthropometric measurements in children with cleft lip and palate. The establishment of a reference database and a step-by-step tutorial will allow reproducibility of measurements in future studies and facilitate the comparison of the clinical status quo with the optimal morphological endpoint. In addition, alar base types based on 3D anthropometric measurements may allow for a more individualised surgical approach to cleft lip and palate treatment.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files).

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

3-dimensional

- FS:

-

facial scanner

- IOS:

-

intraoral scanner

- CLP:

-

cleft lip and palate

- STL:

-

stereolithography

References

Kesting, M., Lutz, R. & Weber, M. (Springer, Cham, (2023).

Millard, D. Cleft craft: the evolution of its surgery—II: bilateral and rare deformities. Bellingham WA: Little Brown & Co (1977).

Duggal, I., Talwar, A., Duggal, R., Chaudhari, P. K. & Samrit, V. Comparative evaluation of nasolabial appearance of unilateral cleft lip and palate patients by professional, patient and layperson using 2 aesthetic scoring systems: A cross sectional study. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 26, 660–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr.12663 (2023).

Rautio, J. et al. Scandcleft randomised trials of primary surgery for unilateral cleft lip and palate: 2. Surgical results. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 51, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/2000656x.2016.1254646 (2017).

Abdullahi, M. A. S., James, O., Olasoji, H. O. & Adeyemo, W. L. Evaluation of the effect of surgical repair on lip-Nose morphometric parameters of patients with unilateral cleft lip using Two-Dimensional photogrammetry: A comparative study between the cleft and the Non-Cleft side. J. West. Afr. Coll. Surg. 13, 73–77. https://doi.org/10.4103/jwas.jwas_257_22 (2023).

Adetayo, A. M., James, O., Adeyemo, W. L., Ogunlewe, M. O. & Butali, A. Unilateral cleft lip repair: A comparison of treatment outcome with two surgical techniques using quantitative (anthropometry) assessment. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 44, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2018.44.1.3 (2018).

Bansal, A., Reddy, S. G., Chug, A., Markus, A. F. & Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M. Nasal symmetry after different techniques of primary lip repair for unilateral complete cleft lip with or without cleft of the alveolus and palate: A systematic review. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 50, 894–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2022.12.006 (2022).

Loo, Y. L., Van Slyke, A. C., Shanmuganathan, P., Reitmaier, R. & Chong, D. K. A guide to bilateral cleft lip markings: an anthropometric study of the normal cupid’s bow. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 59, 926–931. https://doi.org/10.1177/10556656211036329 (2022).

Semb, G., Brattström, V., Mølsted, K., Prahl-Andersen, B. & Shaw, W. C. The Eurocleft study: intercenter study of treatment outcome in patients with complete cleft lip and palate. Part 1: introduction and treatment experience. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 42, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1597/02-119.1.1 (2005).

Semb, G. et al. A scandcleft randomised trials of primary surgery for unilateral cleft lip and palate: 1. Planning and management. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 51, 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2000656x.2016.1263202 (2017).

Carrara, C. F. et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of surgical techniques in neonates with orofacial cleft. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 6, 246–250. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0746.200350 (2016).

Olmos, M. et al. 3D assessment of the nasolabial region in cleft models comparing an intraoral and a facial scanner to a validated baseline. Sci. Rep. 13, 12216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39352-7 (2023).

Shiigi, A. et al. Three-Dimensional quantification of postoperative facial asymmetry in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate using facial symmetry plane. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 61, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/10556656221123276 (2024).

Stebel, A., Desmedt, D., Bronkhorst, E., Kuijpers, M. A. & Fudalej, P. S. Rating nasolabial appearance on three-dimensional images in cleft lip and palate: A comparison with standard photographs. Eur. J. Orthod. 38, 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjv024 (2016).

Xu, Y. et al. Three-dimensional assessment of longitudinal surgical outcome in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate: A modified rotation advancement technique. Clin. Oral Investig. 28, 539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-024-05928-4 (2024).

Yin, J. et al. Short-term surgical outcomes in patients with unilateral complete cleft lip and palate after presurgical Nasoalveolar molding therapy: A three-dimensional anthropometric study. Front. Pediatr. 10, 1101184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.1101184 (2022).

Shaw, W. C. et al. The Eurocleft project 1996–2000: overview. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 29, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1054/jcms.2001.0217 (2001). discussion 141 – 132.

Bugaighis, I., Mattick, C. R., Tiddeman, B. & Hobson, R. 3D facial morphometry in children with oral clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 51, 452–461. https://doi.org/10.1597/12-217 (2014).

Chong, D. K., Somasundaram, M., Ho, E., Dhooghe, N. S. & Fisher, D. M. Comparison of presurgical anthropometric measures of right and left complete unilateral cleft lip and/or palate. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 149, 248e–253e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000008769 (2022).

Farkas, L. G. Anthropometry of the Head and Face (Raven, 1994).

McGraw, K. O. & Wong, S. P. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol. Methods. 1, 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30 (1996).

Shrout, P. E. & Fleiss, J. L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 86, 420–428. (1979).

Bliese, P. D. & Group Size, I. C. C. Values, and Group-Level correlations: A simulation. Organizational Res. Methods. 1, 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814001 (1998).

Brons, S. et al. Uniform 3D meshes to Establish normative facial averages of healthy infants during the first year of life. PLoS One. 14, e0217267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217267 (2019).

Liang, C. et al. Normal human craniofacial growth and development from 0 to 4 years. Sci. Rep. 13, 9641. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36646-8 (2023).

Matthews, H. S. et al. Large-scale open-source three-dimensional growth curves for clinical facial assessment and objective description of facial dysmorphism. Sci. Rep. 11, 12175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91465-z (2021).

Krimmel, M. et al. Three-Dimensional normal facial growth from birth to the age of 7 years. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 136, 490e–501e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000001612 (2015).

Mosmuller, D. G., Griot, J. P., Bijnen, C. L. & Niessen, F. B. Scoring systems of cleft-related facial deformities: A review of literature. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 50, 286–296. https://doi.org/10.1597/11-207 (2013).

Katsube, M. et al. A 3D analysis of growth trajectory and integration during early human prenatal facial growth. Sci. Rep. 11, 6867. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85543-5 (2021).

Kimura, N. et al. Three-dimensional analyses of nasolabial forms and upper lip surface symmetry after primary lip repair in patients with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 47, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2018.11.035 (2019).

Kuijpers, M. A., Chiu, Y. T., Nada, R. M., Carels, C. E. & Fudalej, P. S. Three-dimensional imaging methods for quantitative analysis of facial soft tissues and skeletal morphology in patients with orofacial clefts: A systematic review. PLoS One. 9, e93442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093442 (2014).

Ayoub, A. et al. The validation of an innovative method for 3D capture and analysis of the nasolabial region in cleft cases. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 58, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1055665620946987 (2021).

Marlow, P. J., Mooney, S. W. J. & Anderson, B. L. Photogeometric Cues to Perceived Surface Shading. Curr Biol 29, 306–311.e303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.041

Todd, J. T. & Reichel, F. D. Ordinal structure in the visual perception and cognition of smoothly curved surfaces. Psychol. Rev. 96, 643–657. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.96.4.643 (1989).

Todd, J. T., Egan, E. J. & Kallie, C. S. The darker-is-deeper heuristic for the perception of 3D shape from shading: is it perceptually or ecologically valid? J. Vis. 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.1167/15.15.2 (2015).

Marlow, P. J., Gegenfurtner, K. R. & Anderson, B. L. The role of color in the perception of three-dimensional shape. Curr. Biol. 32, 1387–1394e1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.01.026 (2022).

Wong, K. W. F., Keeling, A., Achal, K. & Khambay, B. Using three-dimensional average facial meshes to determine nasolabial soft tissue deformity in adult UCLP patients. Surgeon 17, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2018.04.006 (2019).

Rizzo, M. I. et al. Volumetric analysis of cleft lip deformity using 3D stereophotogrammetry. Ann. Ital. Chir. 90, 281–286 (2019).

Othman, S. A., Ahmad, R., Asi, S. M., Ismail, N. H. & Rahman, Z. A. Three-dimensional quantitative evaluation of facial morphology in adults with unilateral cleft lip and palate, and patients without clefts. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 52, 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.11.008 (2014).

Peng, R. D. & Hicks, S. C. Reproducible research: A retrospective. Annu. Rev. Public. Health. 42, 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-012420-105110 (2021).

Torrington, E. Reproducibility, scientific rigor and responsibility. Biotechniques 71, 400–402. https://doi.org/10.2144/btn-2021-0066 (2021).

Jan, S. N., Khan, F. A., Ansari, H. H., Hanif, A. & Bajwa, A. Reducing the vermilion Notch in primary lip repairs: Z-plasty versus the Noordhoff triangular flap. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 22, 307–310 (2012).

Pahal, G. et al. Enhancing the vermilion in adult secondary cleft lip repair with a continuous V plasty without closure of the donor defect-a case series. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 52, 374–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2023.11.003 (2024).

Tan, S. P. K., Greene, A. K. & Mulliken, J. B. Current surgical management of bilateral cleft lip in North America. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 129, 1347–1355. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824ecbd3 (2012).

Manchester, W. M. The repair of bilateral cleft lip and palate. Br. J. Surg. 52, 878–882. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800521111 (1965).

Mulliken, J. B. Bilateral complete cleft lip and nasal deformity: an anthropometric analysis of staged to synchronous repair. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 96, 9–23 (1995). discussion 24–26.

Wei, J. et al. Philtrum reconstruction using a Triangular-Frame Conchae cartilage graft in secondary cleft lip deformities. J. Craniofac. Surg. 31, 1556–1559. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000006391 (2020).

Pokropek, A.

Rioux, C., Lewin, A., Odejimi, O. A. & Little, T. D. Reflection on modern methods: planned missing data designs for epidemiological research. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49, 1702–1711. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa042 (2020).

Luo, Y. Evaluating the state of the Art in missing data imputation for clinical data. Brief. Bioinform. 23 https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab489 (2022).

Tutz, G. & Schmid, M. Modeling Discrete Time-to-Event Data. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28158-2

Rauso, R. et al. Alar cinch sutures in orthognathic surgery: Scoping review and proposal of a classification. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 51, 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2021.10.003 (2022).

Yan, Q., Wang, X. & Deng, Y. Classification of Alar abnormalities and the relevant treatments. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 47, 123–128. https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2022.210359 (2022).

Rohrich, R. J. et al. Beyond Alar base resection: contouring of the Alar rim and base. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 152, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000010749 (2023).

Cerkes, N. Alar base reduction: Nuances and techniques. Clin. Plast. Surg. 49, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2021.08.007 (2022).

Singh, P. et al. Smartphone-generated 3D facial images: Reliable for routine assessment of the oronasal region of patients with cleft or Mere convenience? A validation study. BMC Oral Health. 24, 1517. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-05280-9 (2024).

Hartmann, R. et al. Evaluating smartphone-based 3D imaging techniques for clinical application in oral and maxillofacial surgery: A comparative study with the vectra M5. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 29, 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-024-01322-2 (2025).

Seifert, L. B. et al. Comparative accuracy of stationary and Smartphone-Based photogrammetry in oral and maxillofacial surgery: A clinical study. J. Clin. Med. 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13226678 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The present work was performed in fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree Dr. med. for Manuel Olmos. A special thank you goes to our photographer Markus Kohler, who helped with the realisation of Supplementary Material 4.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MO and RL were responsible for study design, data collection, data processing and drafting of the manuscript. CV, KS, SB and LW assisted with data collection through scanning as well as conceptualization. JB contributed to data processing and statistical analysis. MW, RM, AS and MK helped to design and conduct the study. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript through linguistic review. All authors approved the final manuscript before publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg on May 6, 2022 under the application number 22-100-B.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olmos, M., Backhaus, J., Weber, M. et al. 3D anthropometry of the nasolabial region in children aged 3 to 9 months as reference database for clinical assessment. Sci Rep 15, 27443 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11024-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11024-8