Abstract

This research explores the performance, emissions, and combustion behavior of a dual-fuel Reactivity Controlled Compression Ignition (RCCI) engine fueled with sapota oil methyl ester (SOME) blended with butanol, hexanol, and diesel. Sapota oil methyl ester, a still less-researched biodiesel, is evaluated for its synergistic effect when blended with oxygenated additives. Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM), some of the fuel blends like a base blend (B20D80) and others like B20BU10D70 and B20HEX10D70 were compared to enhance engine efficiency and emissions. The findings show that Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) increases with engine load, with Further gains detected under oxygenated blends. With a 10% butanol addition, the BTE improved by about 0.30%, while hexanol blends showed as much as a 0.70% improvement over the reference B20 blend. At the same time, Brake Specific Energy Consumption (BSEC) reduced by 3.29% for butanol and 4.5% for hexanol blends, reflecting improved energy efficiency. Emissions analysis showed that hydrocarbon (HC) and carbon monoxide (CO) emissions have reduced oxygenated additives. With 10% concentrations, HC emissions were reduced by 2.27% (butanol) and 4.65% (hexanol), and the co emissions fell 50% and 63%, respectively. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) increased with load due to incomplete combustion initially, but later reduced in high loads. Smoke emissions were equally reduced by 3.23% (butanol) and 6.66% (hexanol) at 10% levels but increased with increased alcohol content. But emissions did not increase a Little by 1% for butanol and 4.5% for hexanol, emphasizing the need to adopt a careful approach to mixture formulation to deal with environmental concern. The combustion test validated that moderate levels of butanol and hexanol enhance combustion efficiency through enhanced oxygen supply and atomization. The research concludes that B20 + BU10 + D70 and B20 + HEX10 + D70 blends are a viable direction towards sustainable fuel utilization by striking a balance between performance improvement and emission regulation. This work provides insightful contributions towards the optimization of biodiesel-alcohol-diesel blends for clean and efficient engine operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The energy developed for renewability is cheaper and far more efficient than ever. Environmental degradation, along with climatic targets, will have to bring an end to fossil fuel1,2. So, plant-based biofuels, ethanol, and soybean-based biodiesel, are highly promising for replacing fossil Fuel. As such, researchers have estimated a 20% greenhouse gas emission by using soybean-based biodiesel; thus, such a phenomenon would be an important point in sustainability3. Plant-based biofuels, such as biodiesel, are of significant interest in the twenty-first century because they offer promising alternatives to fossil fuels with renewability, sustainability, and lower greenhouse gas emissions. The global implementation of biodiesel initiatives reflects approved blends of diesel and biodiesel, which addresses the challenges and benefits of using biodiesel4.

Adoption of RCCI engines is important in replacing fossil Fuels and sustainability. RCCI engines have improved combustion efficiency by 30% and reduced NOx emissions by 50%. These engines are important for environmental conservation5–7. Development and implementation of new engine technologies, such as RCCI engines, must be subjected to strict testing to ensure sustainable solutions. Testing comprises performance assessments under numerous operating conditions for the demonstration of emission reduction and improvements in efficiency8. Reactivity-Controlled Compression Ignition (RCCI) engines, among several advanced concepts, have garnered much importance in research fields due to their promising prospects in raising efficiency in engines along with lessening emissions9. Reactivity-Controlled Compression Ignition (RCCI) engines indicate significant improvement over an old-fashioned diesel engine from the aspect of dual-fuel mode efficiency with very lesser emissions10. Unlike diesel engines that depend on a lone source of fuel and traditional mechanisms of combustion, RCCI engines are designed with a low-reactivity fuel, such as biodiesel or biogas, mixed with a high-reactivity fuel, such as diesel11,12. A dual-fuel approach allows for very precise control of the combustion process, which therefore results in better performance across a range of operating conditions. RCCI engines demonstrate improved performance on harmful emissions, such as NOx and particulate matter, through the lowering of combustion temperatures and by being better mixtures13.

The flexibility that exists in the fuel blends, such as biodiesel/n-butanol or biogas/diesel blends, makes possible cleaner methods of combustion. For instance, higher ratios of low-reactivity fuels, n-butanol, are efficient in diminishing emission levels during low-load conditions, whereas the input of split combustion techniques has resulted in an improvement during high-load conditions14. High-quality fuel-air mixture is provided through the advanced injector geometries, which results in better emission reduction performances than typical diesel engines15. The use of alternative fuels, such as hydrogen, in RCCI engines offers excellent opportunities for a considerable reduction of CO2 and unburned hydrocarbon emissions16. RCCI engines are a complex and ecologically friendly approach that effectively addresses the conflicts between the need for high efficiency and the stringent emission standards; this marks an important advancement in the field of internal combustion technology. Biofuels in RCCI engines offer many significant advantages over conventional Fuels. It has been proved by research that NOx emissions associated with a biodiesel-diesel blend decrease by 6.7%17.

Additionally, the higher oxygen content in biofuels contributes to more efficient combustion that results in enhanced thermal efficiency. In trials based on research, the combustion of 30% CNG blended with algal biodiesel presents a rise of 4.35% in terms of thermal efficiency from traditional biodiesel18. This is indicative of the power of biofuels in allowing engine performance to enhance and sustain as the core point is made on the issue of sustainability19. Despite all these advantages, several challenges must be addressed to increase the usage of biofuels for RCCI engines20. Among the problems of this phenomenon, high hydrocarbon emissions associated with reduced combustion temperatures remain one of the considerable challenges because they may partially oppose the environmental benefits that otherwise may be accomplished21. The rapid pressure rise rates that occur during dual-fuel operation also raise some important durability issues related to the integrity of components in an engine22,23. Furthermore, the complex fuel injection systems necessary to mix high- and low-reactivity fuels within an RCCI engine make it difficult to integrate them into current engine designs. The production of biofuels, particularly algal biodiesel, is resource intensive and, by this aspect, characterized by significant energy needs in processing. Such a scenario raises important questions about long-term sustainability and scalability in such biofuel production techniques. The introduction of recent technologies and advancements in the production methods can overcome the difficulties24,25.

The present paper discusses the performance, emission, and combustion characteristics of an RCCI engine fueled with blends of sapota oil methyl ester and alcohol. These engines have recently gained attention since they can potentially provide a higher efficiency level along with lower emission potential. Consequently, it is essential to research alternative fuels for these engines.

Research into alternative fuels like butanol, hexanol, and sapota oil methyl ester (SME) have never been in greater demand since their potential to enhance the efficiency of combustion and reduce emissions from compression ignition (CI) engines. Numerous studies for combustion behavior, spray behavior, and combustion characteristics of alternative fuels have confirmed their potential status as clean-energy alternatives26,27.

Potential biodiesel feedstocks have been examined as derived from sapota seed oil. Investigation of the physicochemical properties and combustion behavior of SME-diesel blends in CI engines indicated that B20 (20% SME blend) can provide a brake thermal efficiency (BTE) higher than clean diesel. These were also correlated with emission reduction such as carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC), and smoke; while nitrogen oxide (NOx) emission increased with increased unsaturated fatty acid concentration in SME. More studies have considered the potential of using oxygenates like dimethyl carbonate (DMC) and n-butanol in SME-diesel blend in conventional rail direct injection (CRDi) engines for enhancing combustion properties at the same time altering emission profiles. In addition to diesel, butanol—a biofuel derived from alcohol—has also been explored widely for combustion stability and emission-reducing potential28–30. N-butanol reduces emissions of particles and increases combustion stability, therefore an additive of probable cleaner-burning fuel31–33.

Studies on partially premixed compression ignition (PPCI) engines operated on n-butanol/diesel blends have demonstrated this. In addition, corroborated by spray property tests are butanol’s excellent atomizing properties—that is, smaller droplets sizes and greater evaporation rates—which support more efficient burning. Greater understanding of the spray and flame behavior of the alternative fuels assures optimization of combustion performance. Fuel characteristics, injection parameters, and injector design influence characteristics such as spray tip penetration, Sauter mean diameter, and spray cone angle; physicochemical characteristics have been determined how they impact spray behavior. Especially under high ambient temperatures, since studies on the flame and spray characteristics of butanol-lemon oil blends mixed with petrol in optical engines show, the lower boiling point of butanol allows for greater penetration and evaporation. SMEs, hexanol, and butanol—other CI fuels—also possess significant potential to enhance combustion efficiency and reduce toxic emissions34,35.

Yet, serious concerns in the short term are increasing NOx emissions and demanding optimal mixing ratios. Further research into their fundamental combustion behavior, spray processes, and flame quality will enable one to utilize these fuels efficiently and thus construct sustainable energy systems. These results form the foundation upon which the present work is based, seeking to investigate the performance, emission, and combustion characteristics of an RCCI engine fueled with alcohol blended with sapota oil methyl ester36.

In the study, several fuel blends are investigated, including a base blend B20D80 and experimental blends with butanol B20BU10D70, B20BU20D60, B20BU30D50, and hexanol B20HEX10D70, B20HEX20D60, B20HEX30D50. An RSM methodology using CCD for optimization of interaction between fuel composition, engine load, and other key performance parameters is adopted in this work37–40. The analysis concentrates on BTE and BSEC as the parameters for assessing the combustion efficiency and quality of the atomization of fuel by butanol-hexanol blending. The emission analysis evaluates HC, CO, CO₂, smoke, and NOx, investigates trends under diverse engine loads, and considers variations in fuel compositions, all related to the environmental impacts of blends of biodiesel-alcohol-diesel. Combustion parameter analysis in-cylinder pressure and Heat Release Rate (HRR) would be used to understand the influence of alcohol concentration on combustion behavior. Findings from these analyses add to a deeper understanding of fuel formulation and RCCI engine operation, and insights into how to optimize biodiesel-alcohol blends for better efficiency and cleaner emissions. In the final recommendations, further research is suggested as well as the potential applications of these alternative fuels in internal combustion engines.

Materials and methods

Materials

The fuel used in our research are hexanol, butanol and sapota oil methyl ester. The higher alcohols are bought in a local chemical vendor. Sapota oil methyl ester is obtained initially by mechanical grinding and then processed by transesterification to obtain the methyl ester of sapota oil and to reduce the viscosity of the fuel.

Oil extraction and characterization

Sapota seeds are collected from a local vendor of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu for, and they are made dry in a seed drier for 600C to ensure dryness and the outer skin of the kernels are manually removed and for dryness and then mechanically grinded for extraction of oil. The transesterification was done after characterization of the oil and understood the state of free fatty component in the oil is 1.79%< 2.0%, so a single step transesterification is done using 50 g of raw sapota oil in a conical flask and using KOH + methanol and stirred for 500 rpm using a mechanical stirrer in hot plate heater and carried out for 90 min until phase separation and distilled for glycerin and sapota oil methyl ester41,42.

Gas chromatography and molecular spectroscopy observation

The identification of various chemicals associated with their concentration and retention period is achieved by taking an in-depth study regarding the chemical composition of methyl ester sapota oil with the help of a technique called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, or GC-MS. The significant findings reveal that 1,1-Diethoxy-, and Ethane contributed for the area percentage of 7.87%0.1-Butanol,3-methyl, and2,2-Diethoxypropane took in second and third positions that amounted to 0.35% and 0.37%, respectively. Other notable compounds observed include various alcohols and acids, 1,4-Dimethyl-5-Octyl, and naphthalene. With the column oven set at 40 °C and the injection set at 280 °C, the run was made under specific conditions that facilitated proper identification and quantification of the chemicals present in the sample. Table 1 shows the main components of the GCMS analysis.

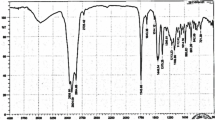

Additionally, the absorbance analysis was done by using the Probe software version 2.70 in a normal mode of measurement ranging from 200 nm up to 1200 nm. Important points include considerable absorbance peaks at the wavelengths of 357.00 nm and 341.00 nm, wherein the absorbance is calculated to be 6.000. The other marked peaks were recorded at wavelengths of 1187.00 nm with an absorbance of 0.624 and at 1062.00 nm at an absorbance of 0.565. Report includes the identification of several chemical compounds with the aid of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and there were remarkable findings such as Ethane, 1,1-Diethoxy-, which represented 7.87% of the total area, while 1-Butanol, 3-methyl- appeared at 0.35%. This general analysis indicates that UV-Vi’s spectroscopy is complemented with GC-MS in identifying and quantifying complex mixtures of chemicals, useful data for future research and applications in chemical analysis and environmental monitoring. Figure 1 indicates the wavelength in nm and absorption rate of the spectrum when the fuel is tested. Table 2 shows that Physiochemical properties of the Fuel used for experimentation.

Experimental engine and set up

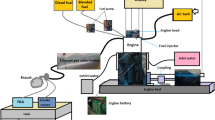

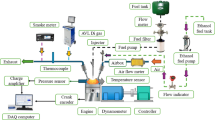

Figure 2 depicts the test engines schematic set up. Two fuel are injected from different fuel and was connected to the flow meter, which is connected to the test engines electronic control unit (ECU), one fuel is injected through the air intake manifold and other in the primary injection of the engine, the fuel that is injected in the air intake manifold is a less reactive fuel and in the primary injector is the fuel with more reactivity. Eddy current dynamometer is controlled by dynamic controller and emission and combustion is measured using emission and combustion analyzer.

Table 3 explains the operation nomenclature of the RCCI engine used, an injector is mounted in the air intake manifold of A conventional single cylinder DI engine and it acts as A secondary injector and conventionally fitted injector acts as the primary injector. The Fuel flow is managed manually by initially calculating the TFC of the engine for all load conditions and then the blends are splinted based on the total volume of the Fuel consumed in two different tanks and the engine is operated in 70% primary injection and 30% in secondary or air intake manifold injection. Table 4 shows the fuel nomenclature.

Calculation of heat release rate

The heat release rate of the engine is calculated using the below equation,

dQ/dθ = γ (P/V) (dV/dθ) + (1/(γ −1)) V (dP/dθ).

where dQ/dθ represents the heat release rate per degree of crank angle (J/°CA), P is the cylinder pressure (Pa), V is the instantaneous cylinder volume (m³), and θ is the crank angle (°CA). The term dP/dθ denotes the rate of pressure change with respect to the crank angle, while dV/dθ represents the rate of volume change with respect to the crank angle. The ratio of specific heats, γ, is typically around 1.35 for diesel engines43,44.

Uncertainty analysis

Uncertainty measures the accuracy errors of an instrument used in the measurement of the current investigation Sources of error include different test conditions, bad sensors, or even assumptions related to fuel45. Scientists use statistics to compute this uncertainty, for instance, determining an error of ± 1.36%. This has large impacts. In environmental research, uncertain pollution values can bias results. For performance, minor measurement variations make it hard to compare biofuels. So, a good uncertainty analysis is crucial. It makes us more confident in our results, informs better engine choices for biofuels, and informs future studies to avoid these errors. Eventually, solving these uncertainties makes biofuel use more successful43,45. Table 5 shows the uncertainty of the measurands.

Optimization using response surface methodology

The investigation aims to employ RSM in analyzing the impacts of diesel-to-hexanol blends with diverse ratios on other performance indicators related to an engine, which involve BTE, BSEC, and other types of emissions; these are in the form of CO, HC, smoke, CO2, and NOx. Carrying out an experiment by central composite design (CCD) methodology will include simultaneous estimation of linear and interaction effects with as minimal as possible experimental runs46. The ratio diesel would be on 70, 60 and 50 volumes %, the ratio butanol to be at the value of 10, 20 and 30% in volumes, the ratio of hexanol would be the same as that of butanol, and the 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100 loading conditions. Each factor will be coded for better analytical purposes, where the actual levels are converted into coded values ranging between − 1 and + 1. The experiments will be carried out based on the CCD matrix; the response variables will be measured systematically in controlled conditions. The coded factor levels and responses will be related through a second-order polynomial regression model. Diagnostic plots and analysis of variance will be used to check model adequacy, which would make the model reliable in predicting responses within the study’s given range. Working with the systematic methodology, it is intended to come up with better fuel formulations that will help in enhancing the efficiency of an engine while being in Line with reduced emissions. The experimental runs were determined as 15 for hexanol and 15 for butanol and experimental runs and combinations are shown in Tables 6 and 732,47–50.

Results and discussions

Performance parameters

The performance parameters of an engine need to be evaluated to optimize efficiency and contribute to sustainability. From a research perspective, brake thermal efficiency, or BTE, is one of the important metrics for gauging how effectively an engine converts fuel energy into mechanical work. The metric is defined as the ratio of useful work output, known as brake power, to the energy input obtained from fuel. This ratio gives insight into the efficiency of combustion processes and the corresponding thermal losses. At the same time, BSEC measures the amount of fuel consumed per unit of power produced, thus directly assessing fuel efficiency. The above parameters significantly decide the trend of experimental investigations and simulations directed towards improving the design and operational efficiency of engines. Through the detailed analysis of Brake Thermal Efficiency and Brake Specific Energy Consumption, researchers become well-capable of unearthing inefficiencies and consequently make suggestions for improvement and advance the design of engines that not only present better performance but also restrain within international sustainability aims by reducing fuel usage and emissions in the automotive industry.

Brake thermal efficiency

Figure 3 shows that Load vs. Brake thermal efficiency. Comparing among different fuel blends, the addition of Hexanol (Hex) and Butanol (Bu) in the B20 + D80 (Sapota Oil Methyl Ester 20% + Diesel 80%) baseline had the tendency to result in better BTE, primarily due to the oxygen content of these alcohols promoting complete combustion. At 100% load, the B20 + BU10 + D70 blend indicated a 0.30% increase in BTE (31.51%) over the B20 + D80 baseline (31.2%), indicating a marginal improvement. But the decrease of BTE to 30.74% at 100% load for an increase in butanol content to 30% (B20 + BU30 + D50) indicates that an optimum blending ratio is achieved. The maximum BTE gain in BTE was with Hexanol blends. The greatest BTE overall of 32.01% was obtained with the B20 + HEX10 + D70 blend at 100% load, a 2.59% gain over the B20 + D80 baseline at the same load. This improved performance is due to Hexanol’s beneficial oxygen content and better combustion properties or energy density to butanol at the given blend fraction. A 30% increase in hexanol concentration, on the other hand, resulted in the lowest BTE at 100% load with B20 + HEX30 + D50 at 30.17%, a 6.09% drop from the maximum BTE of B20 + HEX10 + D70 at 100% load. The intrinsic inefficiency at idle for higher alcohol concentrations was demonstrated by the absolute lowest BTE measured under all conditions, which was 12.99% for B20 + HEX30 + D50 at 0% load. Both butanol and hexanol have lower heating values and potentially longer ignition delays, which can lead to less effective combustion phasing and overall energy conversion. This is especially true when their oxygenation benefits are outweighed by their lower energy density or altered combustion kinetics. As a result, BTE decreases at higher alcohol concentrations51.

Brakes specific energy consumption

Figure 4 shows that Load (%) vs. BSEC (kJ/kWh). The brake specific energy consumption (BSEC) measurement of blends of alcohol and biodiesel under different engine loads is useful information regarding the efficiency of the alternative fuel. There is a consistent trend in all the blends that were tested, and that is the negative correlation of BSEC with engine load: as the load becomes higher, BSEC becomes lower. Increased loads increase the ratio of useful work generated to the pumping and friction losses, with increased overall combustion efficiency and power generation. This phenomenon has been extensively documented in internal combustion engines.

BSEC was affected by the addition of oxygenated alcohols, Butanol (Bu) and Hexanol (Hex), to the B20 + D80 (Sapota Oil Methyl Ester 20% + Diesel 80%). These oxygenate alcohols promote a more complete combustion process by increasing the concentration of available oxygen when the fuel oxidizes. This supports fuel utilization and subsequently decreases the entire consumed fuel. Besides, Butanol and Hexanol can increase the cetane number of the blends, which improves ignition speed and efficiency, thus directly contributing to improved combustion and lower BSEC. Amongst the blends, the B20 + HEX10 + D70 blend consistently showed the optimum BSEC characteristics with the minimum overall BSEC value of 9505 kJ/kWh at 100% load. This represents an efficiency improvement by 3.98% on the B20 + D80 reference (9899 kJ/kWh) at the same load. The B20 + BU10 + D70 blend was also found to benefit with a reduction in BSEC by 3.18% to 9584 kJ/kWh at 100% load against the B20 + D80 reference.

But BSEC was compromised when the alcohol concentration level was increased above optimal. The B20 + HEX30 + D50 blend exhibited the highest BSEC at 100% load (10179 kJ/kWh) of the alcohol-diesel blends, which indicates a 6.62% increase in BSEC over the optimal B20 + HEX10 + D70 blend at full load. Likewise, the B20 + BU30 + D50 mixture shows elevated BSEC values for increased loads (10159 kJ/kwh at 100% load). This reduction in efficiency with elevated alcohol content can be due to their naturally lower energy density and longer ignition delay times, which may be detrimental for optimal phasing of combustion even as there is a benefit from oxygenation. It is also noteworthy to note that the average peak BSEC (least efficiency) was determined at 0% load for the B20 + HEX30 + D50 mix (22760 kJ/kWh), which indicates the challenge of maintaining efficiency at extremely low loads for high alcohol fuels.

Surprisingly, in remarkably high load conditions, it was observed that the convergence of BSEC values among different mixes. This observation suggests that the effect of some fuel properties can be overcompensated by the dominating effects of greater in-cylinder turbulence and improved fuel-air mixture due to naturally greater engine loads, leading to the combustion efficiency to tend to be uniform irrespective of minor fuel variations. In general, the strategic application of oxygenated alcohols like butanol and hexanol in biodiesel blends opens a promising route towards maximized engine fuel efficiency through reduction of BSEC, mostly due to enhanced oxygen availability and improved cetane characteristics. Optimal efficiency, however, calls for judicious blend ratio contemplation as well as interaction with the broad spectrum of engine operating conditions52.

Emission parameters

Emissions from engines are one of the biggest environmental concerns in transportation. While the combustion that occurs within an engine allows it to generate power, it simultaneously emits a host of pollutants, which can damage air quality and human health. The five key parameters of emission that are considered include hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter, also known as smoke. Hydrocarbons are unburned or partially burned fuel constituents, which is significant in forming smog. Carbon monoxide, a toxic gas, is generated by incomplete combustion and can, therefore, deteriorate the transport capacity of blood hemoglobin for oxygen. Carbon dioxide acts as a greenhouse gas hence contributing immensely towards the global threat of climate change. Nitrogen oxides belong to the toxic gases that have been formed in high-temperature combustion processes. They are of pivotal importance in the production of smog, acid rain occurrences, and the aggravation of respiratory diseases. Smoke, consisting mostly of particulate matter, is of great threat to the environment as well as human health. Controls and emission reductions are mandatory for environmental sustainability and public protection. Concisely, these current research and developments involve the optimization of engine design, fuel composition, and after-treatment systems to reduce emissions in the atmosphere.

Hydrocarbon emission

The Fig. 5 below shows the HC emissions of different biodiesel blends at various engine loads. Combustion of a Fuel in an engine involved the observation of hydrocarbon emission at various loading conditions. Most commonly HC emission increases up to 75% load in any engine and then down surges at 100% load due to the preheated combustion chamber in the previous loading conditions.

This trend typically indicates a balance between rising combustion temperatures at higher loads (which should decrease HC) and the likelihood of greater fuel trapped in crevice volumes or localized zones of incomplete combustion as more fuel is being injected. The intentional combination of oxygenated alcohols, Butanol (Bu) and Hexanol (Hex), with the B20 + D80 baseline blend clearly impacted HC emissions. The built-in oxygen of these alcohols is a contributing factor through the supply of extra oxidant during combustion, thus encouraging complete combustion of the Fuel and the consequent decrease in HC. For 100% load, B20 + BU10 + D70 blend posted a 2.22% reduction of HC emissions (44 (ppm)) over B20 + D80 reference (45 (ppm)). Yet the greatest decrease occurred under the hexanol blends, more so the B20 + HEX10 + D70 blend that recorded the lowest HC emission at 100% load (43 (ppm)), which was a 4.44% reduction compared to the baseline. The same blend registered the overall lowest HC emission of 33 (ppm) at 0% load, underlining its consistent capacity to enhance complete combustion throughout the range of operating conditions.

However, when alcohol concentrations exceeded optimal ranges, HC emissions rose. At loads below 75%, the B20 + BU30 + D50 and B20 + HEX30 + D50 blends showed the highest HC emissions of 50 (ppm). There are several reasons why the concentrations of these alcohols lead to a counterintuitive rise in HC, even though they contain oxygen. Suppression in cetane number results in slower ignition and less than ideal combustion conditions and this may be also due to the increase volatility, which restricts more fuel inside the crevice volume and flame quenching.

Lastly, with the increased oxygen content and improved combustion characteristics of the correct blending of butanol and hexanol with biodiesel, the application of butanol and hexanol blending with biodiesel shows a highly feasible approach towards reducing the emissions of HC. However, the foregoing discussion demonstrates how crucial it is to determine the best blending ratio as excessive alcohol will indirectly threaten the completeness of combustion and lead to the higher emissions of HC. This requires the delicate optimization over the entire operating range of the engine54.

Carbon monoxide emission

The Fig. 6 below shows the CO emissions of different biodiesel blends at various engine loads. Carbon monoxide is produced due to incomplete combustion in engines, which is caused by insufficient oxygen supply, poor air-fuel mixing, low combustion temperatures, and fuel characteristics that prevent the complete oxidation of fuel. The analysis of load dependence deals with the way an applied load influences the behavior of a system or material. Carbon monoxide emissions typically decrease with increasing engine load. Under high load conditions, the combustion process is more efficient and, therefore, better fuels are oxidized, and fewer Carbon monoxide are formed. Addition of butanol with the fuel blend reduces the Carbon monoxide emission in comparison with the baseline blend B20 + D80 under high load operation34,55–57. Alcohol mixing has a multifaceted impact on CO emissions, a marker of incomplete burning. The inherent oxygen content in the alcohols reduces CO for optimal mixes such as B20 + HEX10 + D70 (a 4.44% reduction at 100% load over B20 + D80). Improved fuel-air mixing and greater extent of carbon oxidation, especially around fuel-rich zones, are directly aided by this molecular oxygen. Conversely, elevated alcohol content like B20 + BU30 + D50 and B20 + HEX30 + D50 induces CO increases. These increases are normally triggered by a lower blend cetane number, leading to increased ignition delay, and driving combustion into less desirable, cooler cycle zones. Alcohols’ greater latent heat of vaporization can only serve to worsen this by cooling the local combustion environment, which would hinder complete oxidation and promote the production of CO. However, fuels with higher oxygen content are known to burn more readily and this, in turn, makes their combustion processes faster and efficient. It then leads to a reduction in the formation of Carbon monoxide.

Carbon dioxide emission

Figure 7 shows the variation of load expressed in percent and carbon dioxide emission. Carbon dioxide emissions are one of the vital factors that contribute to the greenhouse effect. The emission of carbon dioxide increases if the fuel burning in a compression ignition (CI) engine, or any other type of engine, gets oxidized. The unoxidized fuel releases carbon monoxide, while the leftover carbon is released in the form of uncombusted hydrogen-based carbon, depending on the composition of the fuel. The increase in the level of carbon dioxide levels reflects that greater amounts of fuel have fully combusted or oxidized; however, a smaller amount of carbon dioxide signifies the presence of incomplete combustion or oxidation activities. In the present study, the emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) exhibits an increasing trend with the addition of butanol and hexanol when compared to the base fuel, specifically B20 + D80. Notably, an increase in the percentages of butanol and hexanol beyond 10% has demonstrated a reduction in CO2 emissions. This phenomenon can be attributed to the calorific value and cetane number of the fuels. Both B20 and diesel Fuels can combust appropriately combined with butanol and hexanol; however, when the intake of such alcohols goes beyond 10%, there is a lack of energy. This is because excess oxygen, due to the combustion process, is not used, and in turn, there is a reduced number of carbon molecules to be burnt in the engine. The amount of oxygen that leaves unreacted correlates with the suppression of CO2 emissions. From the results in this figure, it can be concluded that butanol and hexanol blending concentrations greater than 10% are not the best. Comparing butanol and hexanol, however, it is noticed that hexanol has a better combustion efficiency. Thus, its blended biofuel has a higher emission of CO2 than butanol. This phenomenon can be associated with the greater number of carbon molecules in the case of hexanol, which enhance the process of combustion as they facilitate better formation of CO2 through an interaction with the oxygen molecules. In addition to this, increasing the proportion of butanol and hexanol has led to lowering the charge temperature, which may be due to the latent heat of vaporization associated with the alcohols. This phenomenon effectively suppresses the flame propagation within the combustion chamber, leading to incomplete combustion and retention of unburnt hydrocarbons. Besides that, the lower temperature of the combustion products tends to produce a higher emission of carbon monoxide (CO) rather than carbon dioxide (CO2)58–60.

Smoke

Figure 8 describes the variability of Smoke (HSU) emitted with different blends of biodiesel at various load conditions. The smoke emission analysis, an immediate measure of particulate and incomplete combustion, shows strong trends with engine load and fuel constitution. Invariably, smoke emissions show an unmistakable rise with increasing engine load for all blends. This is typical behavior of diesel engines, where increased fuel injection amounts at high loads result in progressively richer combustion zones, favorable for soot generation.

Addition of oxygenated alcohols, Butanol (Bu) and Hexanol (Hex), to the B20 + D80 base mixture, nonetheless, had a profoundly positive effect in the direction of smoke suppression. The major reason for this reduction rests in the inherent oxygen content that is found in butanol and hexanol molecules. This molecular oxygen facilitates the complete combustion of the carbonaceous fuel species, successfully preventing the formation and development of soot particles even in fuel-rich areas. Besides that, these alcohols may also improve the fuel atomization and mixing, additionally overcoming the localized conditions for smoke formation.

Among the blends, hexanol formulations generally produced the optimum smoke suppression performance, with the B20 + HEX30 + D50 blend showing the minimum total smoke emission of 6 units at 0% load, and a remarkable 12.5% decrease to 28 units at 100% load from the B20 + D80 base (32 units). Butanol blends also experienced significant reductions, such that B20 + BU20 + D60 had a 6.25% reduction to 30 units at 100% load. Conversely, the B20 + BU30 + D50 blend experienced the greatest total smoke emission of 33 units at 100% load, even higher than the baseline. Such counter-intuitive enhancement at elevated alcohol concentrations, even when oxygenated, can be explained by reasons like a potentially longer ignition delay (due to lower blend cetane number) resulting in less optimal combustion phasing, or higher latent heat of vaporization effects that may locally cool the flame and hinder complete oxidation of soot. Although strategic application of oxygenated alcohols is extremely effective in suppressing smoke emissions, precise optimization of blending proportions is essential to achieve the maximum benefits and prevent harmful consequences at elevated levels of concentration61,62.

Oxides of nitrogen

The Fig. 9, illustrates investigation on the dynamics of NOx emission linked with several biodiesel blends under an extensive range of engine loads. The NOx emission analysis offers compelling evidence for the synergistic relationship between fuel, engine load, and pollutant formation. Most fundamental observation is the strong, consistent increase in NOx emissions with increasing engine load for all the fuel blends tested. The NOx emission behavior is related to the increasing in-cylinder pressure and temperature with higher loads, which are strongly favorable to the thermal formation of NOx from oxygen and atmospheric nitrogen. The effect of the addition of oxygenated alcohols, Butanol (Bu) and Hexanol (Hex), on NOx emission is subtle. Although alcohols do contain oxygen by their nature, their impact on NOx is usually overshadowed by their role in affecting peak combustion temperatures. On balance, their higher latent heat of vaporization and specific heat capacity can induce a cooling effect on the combustion reaction, one of the main ways of lowering NOx. In the present research work, the B20 + BU30 + D50 mix showed the highest NOx reduction of 4.32% at 100% load of 1373 (ppm) against the B20 + D80 baseline (1435 (ppm)) and the lowest overall NOx emission of 132 (ppm) at 0% load. This indicates that at this greater concentration of butanol, the cooling effects or certain combustion phasing properties more than compensatively offset other contributing factors to NOx. Conversely, the hexanol blends always resulted in greater NOx emissions compared to the baseline, and B20 + HEX10 + D70 had the greatest overall NOx at 100% load of 1500 (ppm). For 100% load, B20 + BU10 + D70 and B20 + BU20 + D60 blends also had minimal increases over the baseline. This increase, despite the oxygen content of alcohols, can be attributed to several reasons. It may be due to an overall rise in combustion efficiency that leads to higher overall flame temperatures, or a change in combustion phasing that creates more advance heat release and thus higher peak local temperatures, both of which enhance NOx formation. Therefore, while alcohols are promising, the precise mix of their properties at a given blend ratio dictates their overall effect on NOx and requires careful optimization3,63.

Combustion parameters

In-cylinder pressure

Figure 10 shows the values of in cylinder pressure rise with respect to crank angle the combustion characteristic addition of butanol and hexanol to B20-diesel blends strongly suggests that the peaks across the fuel blends plotted here relate to an important combustion event. The lowest peak intensity was seen for the baseline blend B20 + D80. BU10, BU20, BU30 (addition of butanol) and HEX10, HEX20, HEX30 (addition of hexanol), increase peak values to high values, with the highest observed in the cases of B20 + BU10 + D70 and B20 + HEX10 + D70. This is due to the presence of higher oxygen content in alcohols, better atomization of fuel, and enhanced premixing, all of which lead to efficient combustion. However, a downward shift in peak intensity at a higher alcohol concentration is found, especially in B20 + BU30 + D50 and B20 + HEX30 + D50, which indicates that higher alcohol concentration may reduce the efficiency of combustion because of changed spray characteristics, ignition delay, or heat release patterns. Hexanol blends also have a little higher peak value than butanol blends at the same concentration due to a higher calorific value and cetane number of hexanol. However, beyond HEX30 and BU30, the gap decreases, thus showing a saturation effect. In general, moderate levels of alcohol addition enhances combustion efficiency. Among the above-mentioned blends, B20 + BU10 + D70 and B20 + HEX10 + D70 are the best, because they combine good combustion characteristics with stable operational features and thus look promising for use as alternative fuels64,65.

Heat release rate

Figure 11 shows the HRR trend for the tested fuel, The HRR trends of the graph make it abundantly evident that the addition of butanol and hexanol to the B20-diesel blend has a major impact on the combustion dynamics. The baseline of B20 + D80 has the lowest peak HRR, which indicates that the combustion process is slower because there are no alcohols present. When butanol (BU10, BU20, and BU30) and hexanol (HEX10, HEX20, and HEX30) are added, the HRR rises to its highest point at B20 + BU10 + D70 and at B20 + HEX10 + D70. This indicates that the combustion process is more efficient because of the increased oxygen supply, improved atomization of the fuel-air combination, and improved premixing. This is demonstrated by the sharply increasing peak in HRR that occurs immediately after the fast energy release phase for the fuels that contain alcohols when they are combined. Nevertheless, the HRR reduces above moderate concentrations of alcohol (BU30 and HEX30), which may be attributed to greater latent heat of vaporization of alcohols, which causes local cooling and enhances ignition delay. As a result, the HRR decreases. The viscosity and spray properties of the fuel are altered when there is an excessive amount of alcohol present in the fuel. This is because the viscosity and spray characteristics of the fuel are in some way incompatible with the correct mixing of the fuel and the air involved in the combustion process. The higher calorific value and cetane number of hexanol causes the blends of hexanol to consistently have a little higher concentration than the blends of butanol at the same concentration levels. This is a crucial point to keep in mind. On the other hand, the trend becomes stable at HEX30 and BU30, indicating that saturation effects are present. This means that additional increases in alcohol concentration do not result in any improvement in combustion performance. The findings therefore show that the addition of alcohol at moderate levels improves the features of combustion, whereas the addition of alcohol at excessive levels results in decreasing returns. The blends B20 + BU10 + D70 and B20 + HEX10 + D70 are the most successful combinations for the goal of generating a high amount of heat and converting energy in an efficient manner66–68.

Response surface methodology optimization

Growth of scientific model using RSM

Response surface methodology is an alternative intensive method for determining correlations relating input and output relationships in complicated systems. The fuel mixture characteristics were studied systematically using a method that included four input variables over two distinct stages, first butanol and then hexanol. The input variables, which comprises the percentage content of diesel and butanol and the variation in load in the initial segments, describe the initial segments. Butanol has been substituted by hexanol in the following stage and the models were run afterwards. Thus, the scientific model was developed incorporating performance and emission characteristics in such a way that it included brake thermal efficiency, brake specific energy consumption, and emission characteristics such as hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), smoke, and nitrogen oxides (NOx)69,70.

A central composite design (CCD) was chosen for the design of experiments to estimate full quadratic effects between the input variables and the output variables. Based on the preliminary studies and experimental capabilities, levels for each input parameters were determined for various fuel combinations. Minitab software generated the experimental design model as shown in the below Tables 8 and 9 shows the point types selected and two level full factorial function was selected for enhance accuracy71–72.

Determining parameters of performance and emissions involved choosing a quadratic model, given that such is most suitable in determining performance. Choosing quadratic models is based on statistical tests on lack of fit and sequential sum of squares. All factors-including linear, interaction, and quadratic terms -are considered when utilizing quadratic models for the major interaction and curvature effects of input parameters73.

Equations (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7) shows the developed quadratic models for performance parameters inclusive of brake thermal efficiency (BTE), Brake specific energy consumption (BSEC), and emission parameters inclusive of HC, CO, CO2, SMOKE and NOx.

Based on the signs and magnitudes of the coefficients, it is possible to obtain insights into the nature and relevance of the input parameters. This makes it feasible to gain insights. Within the experimental parameter range, the mathematical models that were constructed are advantageous tools for estimating the performance of the engine and the pollutants that it produces. The model not only analyses the behavior of fuel composition, but it also provides insight into the interactions that occur between the factors that are input. Table 9 shows that ANOVA table with p and F factors to show model adequacy37.

Anuva and scientific model adequacy checking

This Table 10 reports the results of an analysis of variance (ANOVA). The ANOVA was performed to determine the significance of different variables, including butanol concentration and engine load, on several parameters related to the performance and emissions of the engine. The criteria considered in this study include the following BTE-Brake thermal efficiency, BSFC-brake specific fuel consumption, HC-hydrocarbons, CO-carbon monoxide, CO2-carbon dioxide, smoke opacity, and NOx- nitrogen oxides. The F-value that is a statistical measure to determine the value of each factor is presented in the table along with its corresponding p-value. The presence of a low p-value, that is, below 0.05 most of the time indicates that the given factor has statistically significant influence over the parameter in question. Results of the analysis indicate that all parameters are influenced by engine load. This is evident in the high F-values and low p-values of the factors “load,” “square,” which is associated with the quadratic effect of load, and “Load*Load,” which represents the interaction between load and its square. This should be expected because load on the engine has a strong influence on the features of the combustion process and, consequently, on all the parameters being monitored. The amount of butanol has different degrees of relevance. The result shows that it has an incredibly significant effect on HC emissions. This is proven by the fact that the F-value is highly significant, with a low p-value for the term “butanol.” using this knowledge, the addition of butanol into the biodiesel blend affects the combustion process in a manner such that it tends to reduce the number of hydrocarbons not burnt. The larger p-values, on the other hand, imply that the effect of butanol content on other metrics, including BTE and BSFC, is not as significant as once thought. The “2-Way interaction: Butanol*Load” has minimal relevance on most parameters, suggesting that the influence of butanol content on the parameters is independent of the engine load. This is due to the interaction between butanol content and load, which shows to have only limited significance. Information about the ANOVA table is very meaningful in terms of the elements causing major impacts to the performance as well as characteristics of emission on the engine. It highlights the importance of load on the engine and the influence that concentration plays in butanol in affecting the specific characteristics like hydrocarbon emission of the engine70.

Table 10 contains R-squared values for diverse characteristics of engine performance and emission. This table entails an assessment of how well the model represents the data. R squared is a measure that quantifies the proportion of the variance of the dependent variable that can be explained by the proposed model. From the table above, most of the R-squared values for most of the parameters are remarkably high. These are BTE = 99.03%, CO = 99.65%, CO2 = 97.89%, SMOKE = 97.90%, and NOx = 99.67%. This means that the model is capable enough to express the variability associated with these parameters. Whereas the R-squared for BSFC is much lower than the rest, meaning the model might not be an amazingly effective predictor for BSFC. Further evidence for these results is found in the adjusted R-squared values, which control for the total number of predictors in the model. The fact that the adjusted R-squared values for most of the parameters are high suggests that the model provides a good fit considering the entire number of predictors. The R-squared values that were expected also suggest that most parameters have good predictive ability except for BSFC. The table reveals that the model is a good fit to most the characteristics of engine performance and emission, yet it is conceivable that its predictive ability for BSFC may be limited71.

Contour plots

Figure 12 shows the contour plot of BTE and BSEC with respect to load and butanol. The Contour Plots offer a graphical representation of the interaction effects that the amount of butanol present and the load on the engine have on the brake thermal efficiency (BTE) and the brake specific energy consumption (BSEC). This is demonstrated by the contour plot of BTE, which demonstrates that BTE normally increases with increasing engine load, although the effect of butanol content is less significant. Another overly complicated relationship in the contour plot of BSEC is revealed that depicts a zone with lower values of BSEC at lower loads and intermediate concentration of butanol, which will suggest that combining moderate butanol content with smaller loads can boost the fuel economy. From both data graphs, it is shown that load is a dominant element that affects both BTE and BSEC. The Contour Plots provide valuable information about the interacting effects of these elements and can be used to find the optimal operating conditions for maximum BTE and minimum BSEC so that the best possible results can be obtained44.

Figure 13 shows the Contour plots for HC and CO with respect to load and butanol, Emission plots for hydrocarbon (HC) and carbon monoxide (CO) are shown below and represent the cumulative effect of both the butanol present and load on the engine. As plotted, an increase in load normally increases the emission for both hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide. Because higher loads tend to give less complete combustion, this is to be expected. The curves also indicate that increasing the butanol proportion of the blend tends to increase the amounts of hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide, especially for a higher load. This implies that although butanol presents some promise to enhance specific performance characteristics of the engine, it may, at the same time negatively impact the emission characteristics for hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide, especially when subjected to stresses in terms of demand. These findings reveal the complex interdependence that is present between the type of fuel used, the load imposed on the engine, and the formation of these harmful pollutants74.

Figure 14 shows the percentage variations with the carbon dioxide and smoke released from the engine and which depends on the quantity of butanol in the fuel along with the load on the engine. The graph for carbon dioxide (CO2) shows that an increase in the percentage of butanol in the fuel results in a decrease in the emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), which is an environmentally positive effect. In contrast, both plots clearly show a pattern where increased engine load causes the carbon dioxide and smoke emissions to increase. Significantly, the plots also underscore the point that the impact of butanol concentration on emissions does not follow a constant trend across various levels of engine load. Although butanol possesses the propensity of reducing emission due to carbon dioxide, simultaneously it has potential that can rise to smoke-emitting emissions specially while increasing loads on the engine. This discovery provides insight on a complex and intriguing relationship where an intricate nature can be envisioned as between composition fuel, and a load present upon the engine in relation with varied emission parameters72.

Figure 15, the contour plot for NOx emissions shows how NOx emissions vary with changes in the amount of butanol used and the load on the engine. The plot clearly shows that the amount of NOx emissions increases dramatically as the load on the engine increases. This would be expected since higher loads often result in higher combustion temperatures during combustion. Furthermore, the plot shows that with an increase in the content of butanol, the NOx emissions also increase, especially at higher loads. From this information, it seems that even though butanol may have other benefits regarding the emissions, it will cause a rise in NOx emissions especially when the operating conditions are in high demand. The relation is complex; this realization relates to the three components: composition of fuel, load on engine, and formation of NOx36.

3D response surface plots

Figure 16 Presents the Surface plots describe three dimensions that depict exactly how the BTE and BSEC change by response to all different combinations of how much butanol is mixed and how loaded up the engine is. Here is a surface plot for the BTE clearly indicating an uptick in slope by load in fact indicating when it’s cranked up large, larger amounts generally have been experienced as relating to BTE. The effect of butanol concentration on BTE does not look so significant as it was. In contrast, the plot of the BSEC depicts a relationship that is much more convoluted. The results show that the BSEC decreases first with load rise which means the fuel economy has increased. BSEC, however begins to rise once more for increasing the load. The effect of butanol content on BSEC is evident from the downward slopes of the surfaces. This indicates that high butanol content frequently tends to cause a reduction in BSEC, which represents an enhancement in the fuel economy. These three-dimensional visualizations represent interaction effects of butanol content and load on engine performance and fuel efficiency, providing a comprehensive insight into the subject matter70.

Figure 17 the Surface Plots provides a three-dimensional view about the way changes in HC and CO emissions based on the volume of butanol added to the engine and on the load given to the engine. In a glance at the HC plot, one can view an increasing pattern clearly; in other words, this emission grows as the volume of butanol and the amount of load add higher. In an equivalent manner, the plot of CO also shows a trend upwards; thus, it is an indication that higher loads result in greater CO emissions besides increasing the butanol content in the mixture. Such three-dimensional visualizations can validate earlier investigations’ findings and provide evidence of the intricate relationship that exists between the load on the engine, the composition of the fuel, and the processes that lead to their development74.

Figure 18 shows the three-dimensional charts depicting the complex relationship between the quantity of butanol, the load on the engine, and the emissions of carbon dioxide and smoke. The plot indicates that there is an initial rise with load for CO2, which is followed by a reduced rate of increase or even a plateau that occurs. This tendency of increasing in the amount of butanol can be said to lead to reduced carbon dioxide that is an aspect of improvement on the combustion process. However, the Smoke plot shows a rising trend and yet both the load and the amount of butanol have increased. From this information, it is derived that the rising butanol concentration and the heavier loads both may lead to smoke emissions. Such three-dimensional visualization provides full knowledge of the interactions of these factors to contribute to the performance of the engine and to the pollutants which it emits6.

In this three-dimensional plot Fig. 19, NOx emissions produced is depicted in terms of concentrations butanol and engine load. An upward trend from the plot suggests that based on the amount of butanol present and load, an increase in NOx emissions will be produced. This would imply that butanol, although it has some potential benefits by at least lowering other emissions, may increase the NOx emission, especially with higher loads and elevated butanol concentrations. This primarily is because it incorporates the fuel with other emissions. Since the surface is so steep along the load axis, the plot shows the impact on the generation of NOx from the load in a strong way. This is a typical example of the complex relationship between the composition of the fuel, the load on the engine, and the generation of NOx emissions44.

Optimization of input parameters using RSM to achieve desired engine performance and emission characteristics

Optimization Objectives/Constraints for Performance Parameters and Emission Parameters Using Various Engine Configurations Table 11 The target is to optimize with respect to various engine performance parameters and emission characteristics. Optimization should be minimized to NOx, Smoke, CO, and HC, but CO2 and BTE, brake thermal efficiency should be maximized. Acceptability-wise, each response must have identical lower restrictions and upper restrictions. These demarcated goal line and limitations will be strategies during the optimization progression to identify the best operating conditions and fuel compositions to meet the desired performance and emission targets. Table 12 shows that outlines the optimization goals and constraints for various engine performance and emission parameters74.

The Table 12 shows the optimal solution for engine performance and emission characteristics. Under the optimal condition, it can be determined to be 10% butanol content in Fuel and an engine load of 17.1717%. Then, the given predicted values are nox, smoke, CO2, CO, HC, BSEC, and BTE at these conditions. The “fit” column must replicate the goodness-of-fit of the model forecast for each response variable at the augmented resolution. The value 0.613052 in “composite desirability” is the overall measure that indicates how well an optimized solution would Meet the given goals and constraints, with better values being superior performance. Table 13 shows that presents the optimized solution for the engine performance and emission characteristics.

The Table 14 gives some predictions of different engine performance and emission characteristics at the optimized operating conditions of 10% butanol content and 17.1717% load. The table represents the predicted values for nox, smoke, CO2, CO, HC, BSEC (Brake specific energy Consumption), and BTE (Brake Thermal Efficiency). The table provides the predicted values, in addition to the standard error of the fit (SE Fit) for each response variable, which gives an indication of the precision by which the model can predict. More importantly, it shows 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and 95% prediction intervals (PIs). The confidence intervals give a range in which the actual mean value of the response variable will fall, and the prediction interval gives a range in which a Future observation of the response variable will fall. Such intervals give valuable information about the uncertainty associated with predictions of a model. butanol set to 10 and load is set to 17.717.

Conclusion

The research examines the performance, emission, and combustion behavior of an RCCI engine using blends of sapota oil methyl ester (SOME), butanol, hexanol, and diesel. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was used to optimize major findings for better efficiency and lower emissions.

-

Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) was enhanced with engine load and showed notable improvement when using blends of butanol and hexanol. Use of a 10% butanol blend (B20BU10D70) improved the brake thermal efficiency by 0.30%, while B20HEX10D70 blend improved by 0.70% compared to the control B20D80 blend.

-

The Brake Specific Energy Consumption (BSEC) reduced by 3.29% for B20BU10D70 and 4.5% for B20HEX10D70, reflecting improved fuel efficiency.

-

Hydrocarbon (HC) emissions reduced by 2.27% for B20BU10D70 and 4.65% for B20HEX10D70, while carbon monoxide (CO) emissions reduced by 50% and 63% for butanol and hexanol blends, respectively. Smoke emissions reduced by 3.23% in B20BU10D70 and 6.66% in B20HEX10D70. Nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions were increased by 1% with butanol and 4.5% with hexanol, showing a requirement of precise optimization of the blend for better performance.

-

A mid-level alcohol blend generated higher heat release rate (HRR) and in-cylinder pressure, thus enhancing combustion efficiency. Greater alcohol contents decreased the efficiency of combustion by affecting the dynamics of the spray and delaying ignition.

-

The B20 + BU10 + D70 and B20 + HEX10 + D70 mixtures offered optimal balance between higher efficiency and lower emissions.

The current research is based on sufficient evidence that the use of alternative biodiesel-alcohol mixtures in RCCI engines could be an effective strategy to optimize the performance of internal combustion engines without breaching tight pollution standards.

Software Used: The study was conducted using Minitab version 20.3 and the software is accessible at the official website: https://www.minitab.com/en-us/support/downloads/.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Papu, N. H., Lingfa, P. & Dash, S. K. Euglena Sanguinea algal biodiesel and its various diesel blends as diesel engine fuels: a study on the performance and emission characteristics. Energy Sources Part. Recovery Utilization Environ. Eff. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2020.1798566 (2020).

Dash, S. K. et al. Investigation on the adjusting compression ratio and injection timing for a DI diesel engine fueled with policy-recommended B20 fuel. Discov Appl. Sci. 6, 387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-024-06076-w (2024).

Ramachandran, E. et al. Prediction of RCCI combustion fueled with CNG and algal biodiesel to sustain efficient diesel engines using machine learning techniques. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 51:103630 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2023.103630 (2023).

Yilmaz, N. Effects of intake air preheat and fuel blend ratio on a diesel engine operating on biodiesel–methanol blends. Fuel 94, 444–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.10.050 (2012).

Singh, A. P., Kumar, V. & Agarwal, A. K. Evaluation of comparative engine combustion, performance and emission characteristics of low temperature combustion (PCCI and RCCI) modes. Appl. Energy. 278(August), 115644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115644 (2020).

Kumaran, P., Natarajan, S., Kumar, S. M. P., Rashid, M. & Nithish, S. Optimization of diesel engine performance and emissions characteristics with tomato seed blends and EGR using response surface methodology. Int. J. Automot. Sci. Technol. 7 (3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.30939/ijastech.1326036 (2023).

Lionus Leo, G. M., Jayabal, R., Kathapillai, A. & Sekar, S. Performance and emissions optimization of a dual-fuel diesel engine powered by cashew nut shell oil biodiesel/hydrogen gas using response surface methodology. Fuel 384 (133960). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.133960 (2025).

Jia, Z. & Denbratt, I. Experimental investigation of natural Gas-Diesel Dual-Fuel RCCI in a Heavy-Duty engine. SAE Int. J. Engines. 8 (2), 797–807. https://doi.org/10.4271/2015-01-0838 (2015).

Fathi, M., Ganji, D. D. & Jahanian, O. Intake charge temperature effect on performance characteristics of direct injection low-temperature combustion engines. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 139 (4), 2447–2454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08515-y (2020).

LEE, T. Y. K. Combustion and emission characteristics of wood pyrolysis Oil-Butanol blended fuels in a Di diesel engine. Int. J. …. 13 (2), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12239 (2012).

Fu, Y., Hu, E. & Xia, Z. HCCI technology using hydrogen energy and artificial intelligence. Appl. Comput. Eng. 11 (1), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-2721/11/20230226 (2023).

Sanyasi Rao, S., Paparao, J., Raju, M. V. J. & Kumar, S. Effect of nanoparticle-doped biofuel in a dual-fuel diesel engine with oxy-hydrogen gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 70 (April), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.05.131 (2024).

Brandão, M., Heijungs, R. & Cowie, A. L. On quantifying sources of uncertainty in the carbon footprint of biofuels: crop/feedstock, LCA modelling approach, land-use change, and GHG metrics. Biofuel Res. J. 9 (2), 1608–1616. https://doi.org/10.18331/BRJ2022.9.2.2 (2022).

Sagin, S. V. et al. Use of biofuels in marine diesel engines for sustainable and safe maritime transport. Renew. Energy. 224 (February). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.120221 (2024).

Jaral, S. V. & Singh and M.S., Recent Advances in Sustainable Technologies, ISBN 9789811609756, (2021).

Mahmud, A. S. & Zachary, D. S. A matrix representation for sustainable activities. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05750-6 (2022).

Chen, H., Wang, X. & Pan, Z. Effect of operating conditions on the chemical composition, morphology, and nano-structure of particulate emissions in a light hydrocarbon premixed charge compression ignition (PCCI) engine. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 141716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141716 (2021).

Kumar, N. P., Vijayabaskar, S., Murali, L. & Ramaswamy, K. Design of optimal Elman recurrent neural network based prediction approach for biofuel production. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 8565. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34764-x (2023).

Deepak, H. S., Veerabhadrappa, K. & Tharakeshwar, T. K. Optimization of the design of shell and double concentric tube heat exchanger using the TLBO algorithm. J. Mines Metals Fuels. 119–130 https://doi.org/10.18311/jmmf/2023/43184 (2024).

Padmanaban, J., Kandaswamy, D. A., Joshua, P. J. T. & Natarajan, A. Statistical analysis of engine fueled with two identical lower aromatic biofuel blends at various injection pressure. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 46 (1), 7720–7735. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2024.2368495 (2024).

Alemayehu, G., Nallamothu, R. B., Firew, D. & Gopal, R. Experimental investigation on impact of EGR configuration on exhaust emissions in optimized PCCI-DI diesel engine. J. Eng. 2022, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5688842 (2022).

Prashanth, K. & Srihari, S. Emission and performance characteristic of a PCCI-DI engine fueld with cotton seed oil bio-diesel blends. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 11 (9), 5965–5970 (2016).

Parthasarathy, M. et al. Experimental investigation of strategies to enhance the homogeneous charge compression ignition engine characteristics powered by waste plastic oil. Energy Convers. Manag. 236 (March), 114026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114026 (2021).

Roschat, W. et al. A highly efficient and cost-effective liquid biofuel for agricultural diesel engines from ternary blending of distilled Yang-Na (Dipterocarpus alatus) oil, waste cooking oil biodiesel, and petroleum diesel oil. Renew. Energy Focus. 48 (January), 100540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ref.2024.100540 (2024).

Ramalingam, K. et al. An assessment on production and engine characterization of a novel environment-friendly fuel. Fuel 279 (May), 118558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118558 (2020).

Hezam, I. M., Cavallaro, F., Lakshmi, J., Rani, P. & Goyal, S. Biofuel production plant location selection using integrated picture fuzzy weighted aggregated sum product assessment framework. Sustainability 15 (5), 4215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054215 (2023).

RAJAK, U., KUMAR, N. A. S. H. I. N. E. P. & CHAURASIYA, P. A numerical investigation of the species transport approach for modeling of gaseous combustion. J. Therm. Eng. 7 (Supp 14), 2054–2067. https://doi.org/10.18186/thermal.1051312 (2021).

Jatadhara, G. S., Chandrashekhar, T. K., Banapurmath, N. R., Nagesh, S. B. & Keerthi Kumar, N. Reactivity controlled compression ignition engine powered with plastic oil and B20 Karanja oil Methyl ester. J. Mines Metals Fuels. 186–192. https://doi.org/10.18311/jmmf/2023/45584 (2023).

Ramalingam, K., Kandasamy, A. & Chellakumar, P. J. T. J. S. Production of eco-friendly fuel with the help of steam distillation from new plant source and the investigation of its influence of fuel injection strategy in diesel engine. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 (15), 15467–15480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04773-3 (2019).

Ramalingam, K., Vellaiyan, S., Kandasamy, M., Chandran, D. & Raviadaran, R. An experimental study and ANN analysis of utilizing ammonia as a hydrogen carrier by real-time emulsion fuel injection to promote cleaner combustion. Results Eng. 21 (February), 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101946 (2024).

Gurusamy, M. & Subramanian, B. Study of PCCI engine operating on pine oil diesel blend (P50) with benzyl alcohol and diethyl ether, Fuel 335(x):127121, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.127121

Ramalingam, K. M., Kandasamy, A., Subramani, L., Balasubramanian, D. & Paul James Thadhani, J. An assessment of combustion, performance characteristics and emission control strategy by adding anti-oxidant additive in emulsified fuel. Atmos. Pollut Res. 9 (5), 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2018.02.007 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Fuel modification flash boiling atomization and combustion in reciprocating engines. J. Energy Inst. 111 (April), 101268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2023.101268 (2023).

Perumal Venkatesan, E. et al. Performance and emission reduction characteristics of cerium oxide nanoparticle-water emulsion biofuel in diesel engine with modified coated piston. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 (26), 27362–27371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05773-z (2019).

Venu, H., Raju, V. D., Lingesan, S., Elahi, M. & Soudagar, M. Influence of Al2O3nano additives in ternary fuel (diesel-biodiesel-ethanol) blends operated in a single cylinder diesel engine: performance, combustion and emission characteristics. Energy 215, 119091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119091 (2021).

Ramachandran, E., Krishnaiah, R., Perumal Venkatesan, E., Medapati, S. R. & Sekar, P. Experimental investigation on the PCCI engine fueled by algal biodiesel blend with CuO nanocatalyst additive and optimization of fuel combination for improved performance and reduced emissions at various load conditions by RSM technique. ACS Omega. 8 (8), 8019–8033. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c07882 (2023).

Shirneshan, A. R., Almassi, M., Ghobadian, B. & Najafi, G. H. Investigating the effects of biodiesel from waste cooking oil and engine operating conditions on the diesel engine performance by response surface methodology. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. - Trans. Mech. Eng. 38 (M2), 289–301 (2014).

Saheban Alahadi, M. J., Shirneshan, A. & Kolahdoozan, M. Experimental investigation of the effect of grooves cut over the piston surface on the volumetric efficiency of a radial hydraulic piston pump. Int. J. Fluid Power. 18 (3), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/14399776.2017.1337440 (2017).

Eslami, M. J., Hosseinzadeh Samani, B., Rostami, S., Ebrahimi, R. & Shirneshan, A. Investigating and optimizing the mixture of hydrogen-biodiesel and nano-additive on emissions of the engine equipped with exhaust gas recirculation. Biofuels 14 (5), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/17597269.2022.2148877 (2023).

Shirneshan, A., Amiri, M. & Zare, A. Effects of oxygen addition on thermal and pollutant emission characteristics of a cylindrical furnace fueled with 1-Hexanol–biodiesel–diesel blends. Energy Rep. 10, 2080–2089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2023.09.014 (2023).

Govindasamy, M., Dhariyasamy, R. & Rajendran, S. Sapota Methyl ester: analysis of combustion and emission characteristics for partial replacement of diesel in a CI engine. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 43 (1), 5076–5084. https://doi.org/10.1080/01430750.2021.1934114 (2022).

Jayabal, R., Thangavelu, L. & Velu, C. Experimental investigation on the effect of ignition enhancers in the blends of Sapota biodiesel/diesel blends on a CRDi engine. Energy Fuels. 33 (12), 12431–12440. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b02521 (2019).

Parida, S. et al. Production of biodiesel from waste fish fat through ultrasound-assisted transesterification using petro-diesel as cosolvent and optimization of process parameters using response surface methodology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (17), 25524–25537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-32702-6 (2024).

Varuvel, E. G., Seetharaman, S., Shobana Bai, J., Devarajan, F. J., Balasubramanian, D. & Y., and Development of artificial neural network and response surface methodology model to optimize the engine parameters of rubber seed oil – Hydrogen on PCCI operation. Energy 283 (April), 129110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.129110 (2023).

Ramalingam, K. et al. An assessment on production and engine characterization of a novel environment-friendly fuel. Fuel 279 (118558). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118558 (2020).

Elkelawy, M., Shenawy, E. A., El, Mohamed, S. A., Elarabi, M. M. & Bastawissi, H. A. E. Impacts of using EGR and different DI-fuels on RCCI engine emissions, performance, and combustion characteristics. Energy Convers. Management: X. 15 (May), 100236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2022.100236 (2022).

Azizul, M. A. et al. Improvement of combustion process and exhaust emissions with premixed charge compression ignition. J. Automot. Powertrain Transp. Technol. 2 (1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.30880/japtt.2022.02.01.002 (2022).

Gani, A. Fossil fuel energy and environmental performance in an extended STIRPAT model. J. Clean. Prod. 297:126526 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126526 (2021).

Natarajan, A., Kandasamy, A., Venkatesan, P., Saleel, C. A. & E., and Experimental investigation on the effect of graphene oxide in higher alcohol blends and optimization of injection timing using an ANN method. ACS Omega. 8 (44), 41339–41355. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c04895 (2023).

Dhileepan, S., Viswanathan, K., Esakkimuthu, S. & Balasubramanian, D. Optimization of CRDI engine operating parameters using response surface methodology utilizing lemon Peel oil biofuel enriched with hydroxy gas. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 190 (PA), 1506–1519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.07.108 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Optimization of a cold thermal energy storage system with micro heat pipe arrays by statistical approach: Taguchi method and response surface method. Renew. Energy. 238, 121899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.121899 (2025).

Joshua, P. J. T., Kandasamy, A., Venkatesan, E. P. & Saleel, C. A. Experimental study on sustainability involving the Pugh matrix on emission values of High-Temperature air in the premixed charged compression ignition engine. ACS Omega. 8 (44), 41243–41257. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c04694 (2023).

Kale, A. V. & Krishnasamy, A. Application of machine learning for performance prediction and optimization of a homogeneous charge compression ignited engine operated using biofuel-gasoline blends. Energy Convers. Manag. 314 (May), 118629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118629 (2024).

Singh, A. P., Kumar, D. & Agarwal, A. K. Introduction to Alternative Fuels and Advanced Combustion Techniques as Sustainable Solutions for Internal Combustion Engines, ISBN 9789811615122, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-1513-9_1

Ramalingam, K., Kandasamy, A. & Joshua Stephen Chellakumar, P. J. T. Production of eco-friendly fuel with the help of steam distillation from new plant source and the investigation of its influence of fuel injection strategy in diesel engine. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 (15), 15467–15480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04773-3 (2019).

Ramalingam, K., Kandasamy, A., Subramani, L., Balasubramanian, D. & Paul James Thadhani, J. An assessment of combustion, performance characteristics and emission control strategy by adding anti-oxidant additive in emulsified fuel. Atmos. Pollut Res. 9 (5), 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2018.02.007 (2018).

Sivalingam, A. et al. Citrullus colocynthis - an experimental investigation with enzymatic lipase based Methyl esterified biodiesel. Heat. Mass. Transfer/Waerme- Und Stoffuebertragung. 55 (12), 3613–3631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-019-02632-y (2019).

Pan, D. et al. Study on the effect of Two-Stage injection strategy for Coal-to-Liquid/Gasoline Reactivity-Controlled compression ignition combustion mode. ACS Omega. 9 (16), 18191–18201. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c10315 (2024).

Krishnamoorthi, M., Malayalamurthi, R., He, Z. & Kandasamy, S. A review on low temperature combustion engines: performance, combustion and emission characteristics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 116 (109404). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109404 (2019).

R, S. M. & Nandakumar, S. The effect of air preheating on the performance and emission characteristics of a DI diesel engine achieving HCCI mode of combustion. Int. J. Theoretical Appl. Mech. 12 (3), 411–421 (2017).