Abstract

The Amazon Continental Shelf (ACS) stretches for more than 2500 km along the coast of northern Brazil, where it is influenced directly by the discharge of the Amazon River, which deposits enormous quantities of organic matter at its mouth. Despite the extraordinary importance of this region, it is still among the least-studied sectors of the Brazilian coast. The present study, which is based on the data generated by the continuous monitoring conducted by the National Center for Research and Conservation of the Marine Biodiversity of Northern Brazil (CEPNOR/ICMBio) and the systematic review of the databases of reference collections, provides the most comprehensive inventory of the marine biodiversity of the ACS compiled up to now. A total of 3286 species were identified, 1247 more than previous studies, including primarily bony fish (28%) microorganisms (15%) and molluscs (14%). Considering the conservation status of the species, 67 of which are threatened at some level according to the list of endangered species in Brazil, mainly cartilaginous fish (40%), bony fish (31%) and seabirds (11%). The results of the present study reveal hotspots of biodiversity, especially near offshore oilfields and fishing grounds, raising concerns about the potential impact of human activity in the region. These findings emphasize the need for systematic ecosystem management combined with continuous monitoring, to mitigate these threats to the biodiversity of the ACS, while also reinforcing the importance of integrating scientific and conservation efforts to protect this unique, but vulnerable biome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Amazon Continental Shelf (ACS), or Brazilian Amazon Coast, stretches for more than 2500 km of the western equatorial Atlantic, from Oiapoque River, on the border between Brazil and French Guiana, and the Parnaiba River, in the Brazilian state of Piauí1,2,3. This coast forms the largest known continuous estuarine environment, which encompasses innumerable characteristic indentations and inlets dominated by mangrove forests4. This system provides nutrients for the adjacent marine waters, including those of the Great Amazon Reef System5,6.

This region has two well-defined seasons, rainy and dry (with transition periods), and a dynamic macrotidal regime, which is influenced by the input of the Amazon River, the winds of the intertropical convergence zone and the North Brazil Current and trade winds1,7,8,9. The cycle of the tides and local rainfall patterns are responsible for the abundant nutrients and the maintenance of the region’s demersal fauna10,11,12,13.

The ACS has a extreme complexity of the fluvial-oceanic dynamics14, and is reflected in the enormous diversity of the local aquatic fauna13,15. Up until now, however, the most comprehensive studies of this biodiversity have been based on the analysis of the bycatch of commercial fisheries16,17, the assessment of the threatness level of the species18,19,20 or the analysis of the occurrence of species in the different vertical zones of the water column21. Most of these records have been published in a range of periodicals, while the original data are dispersed among different official public databases22.

Given its inestimable biodiversity, the ACS is the target of considerable interest from commercial operations22, given that it represents, based on the most recent data, the second most productive fishery zone off the Brazilian coast23. According to IBAMA technical reports from 2007, the total annual fishery production of this zone was estimated to be 129,981.5 tons24. This is likely an underestimate22, however, and more recent studies have concluded that the actual production may be four to 12 times greater, considering all the non-target biodiversity impacted by local fisheries25,26.

In addition to the impact of its fisheries, the ACS recently became the target of an intense environmental debate between government, oil companies and environmental agencies, related to the licensing of the exploitation of oil and gas fields in the Pará-Maranhão basin, which has estimated reserves of between 20 and 30 billion barrels of oil27. Licensing applications have revealed the probability of highly significant impacts, and have almost invariably been deferred by the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources - IBAMA28. These rulings have been based on the extreme socio-environmental vulnerability of the region, given its rich and still partially undefined biodiversity, in addition to the presence of traditional populations and protected areas29.

Adding to the conflicts described above, the analysis of the impacts of ongoing climate change on the landscape of the Amazon region is still incipient30,31. Given all these questions, it is extremely important to determine which species are present in the ACS, in order to provide a solid baseline for the discussion of the strategies needed to overcome these challenges17,32.

In this context, the National Center for Research and Conservation of the Marine Biodiversity of Northern Brazil of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (CEPNOR/ICMBio) – an autarchy of the Brazilian Environment Ministry (MMA) – has been monitoring the marine biodiversity of the ACS, based on fishery mortality, in collaboration with the Goeldi Museum (Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, MPEG). Based on these efforts, the present study compiled the most comprehensive inventory of the marine biodiversity of the northern coast of Brazil produced to date. These data were assessed in relation to the real and potential impacts facing the region, to provide insights for the effective management and conservation of local biodiversity occurring on the ACS.

Methods

The inventory of the biodiversity of the ACS was compiled based on (1) the database of the CEPNOR/ICMBio Fishery Impact Monitoring Program, and (2) a review of the validated data on the marine biota of the study area available online from museums and reference collections.

CEPNOR monitoring program

During the CEPNOR/ICMBio monitoring program, the data were collected by scientific observers on board, who collected data on licensed commercial fishing vessels during their operations off the northern coast of Brazil. These fishing fleets target shrimp (Penaeus sp), Laulao catfish (Brachyplatystoma vaillantii), spiny lobster (Panulirus sp), acoupa weakfish (Cynoscion acoupa), red snapper (Lutjanus purpureus), and miscellaneous fish, and were monitored between 1998 and 2024.

The vessels were monitored during different periods, and during each excursion, the onboard observer recorded data on a field chart, including the georeferenced location of the catch, and the occurrence of the different morphotypes, based on photographic records (Nikon Coolpix AW130 Geotag) and the preliminary identification of the species at sea.

Samples of the morphotypes and the photographic images were sent to CEPNOR and the Goeldi Museum in Belém for confirmation of the taxonomic identification and inclusion in the reference collection. The taxonomic identification of the species was confirmed using identification keys and, whenever necessary, consultations with specialists.

The georeferenced locations were used to generate maps of the monitored areas, which were subsequently combined in a single shapefile for the definition of the limits of each fishery (Fig. 1). In the specific case of “miscellaneous fish”, the fishing zone was defined based on the coordinates available in Normative Instruction 13/201333. The area of the Amazon Reef System6,34,35 was also included in the map (Fig. 1), as were the minimum and maximum extension of the Amazon plume34 and the offshore oil exploration concession blocks36. All areas were mapped using QGis 3.40 software.

Area monitored by the National Center for Research and Conservation of the Marine Biodiversity of Northern Brazil of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (CEPNOR/ICMBio), showing the principal offshore licensed fishing zones, the oil exploration concession blocks36, the minimum and maximum extension of the Amazon plume34, and the Amazon Reef System6,34,35. Brazilian states: AP = Amapá, MA = Maranhão, and PA = Pará.

Online data search

The online survey of species from the ACS was based on a search of all the databases that contain records of marine species from the northern coast of Brazil, that is, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF: https://www.gbif.org/), the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS: https://obis.org/), the Marine Mammals Monitoring Support System (SIMMAM) and other major projects in the study area (JICA and REVIZEE).

Initially, the polygons that delimit the ACS were generated in the QGIS 3.38 software, then, all georeferenced occurrence points existing in the official databases were inserted into the map, extracting only the records within the polygon in the ACS. Finally, an active search for inconsistent data was performed, removing errors, such as the occurrence of primates and Amazonian birds incorrectly inserted in the official databases.

The study did not collected data from bibliographic reviews on species identification and occurrences in the ACS. The analysis objective was catalog species records that contains information on latitude, longitude, data origin and that have been validated in scientific collections, data generally not reported in scientific articles due to the authors’ restrictions on access to their databases.

All the species records were mapped in the QGis 3.38 software. Species taxonomy was updated based on WoRMS, the World Register of Marine Species (https://www.marinespecies.org/).

Total biodiversity of the ACS

The species identified during the CEPNOR monitoring and online search were organized into 14 taxonomic groups: (1) algae (green, brown, red, and golden algae), (2) bony fish, (3) cartilaginous fish, (4) cetaceans, (5) decapod crustaceans, (6) echinoderms, (7) microorganisms (predominantly cercozoans, diatoms, dinoflagellates), (8) molluscs, (9) other crustaceans (predominantly isopods, copepods, and cirripeds), (10) other invertebrates (brachiopods and chaetognaths), (11) seabirds, (12) soft and hard corals (cnidarians, poriferans, tunicates, and bryozoans), (13) turtles, and (14)worms (predominantly annelids, flatworms, nematodes).

The conservation status of each species was also defined based on the red lists of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN: www-iucnredlist-org) and the Brazilian Environment Ministry (MMA: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-mma-n-148-de-7-de-junho-de-2022-406272733). The data on the occurrence (total species richness and threatened species only) and density per taxon were used to produce heat maps, using the Kernel density estimator, run in QGis 3.384 software.

Statistical analyses

As the fishery zones overlap, the statistical analyses of the species occurrence were based on the distribution of the bottom-substrate megahabitats proposed by Araujo et al.37, which divide the continental shelf into three categories – (i) the Area Influenced Permanently by the Amazon Plume (AIP), which includes “mud near the coast”, “mixed mud and sand”, “lightly laminated mud”, and “sandy silt on the proximal shelf”, (ii) the Area of Transition (ATR), composed on “mud mixed with sand”, and (iii) the Amazon Reef Area (ARA), which includes “reefs and rhodoliths”, “rhodoliths”, “bryolites”, and “other carbonate sediments”.

To compare species richness between areas, the residues were previously evaluated with a Shapiro-Wilk normality test, which revealed asymmetry (p < 0.001), and the Levene test, which demonstrated heteroscedasticity (p < 0.001), even after logarithmic transformation. Considering the test results, the richness was compared using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. The rarefaction method of Gotelli and Colwell38 was then applied to illustrate and compare the species richness per megahabitat. The application of this method permitted the comparison of the megahabitats taking into account their different sampling dimensions, unequal sampling effort, and the absence of data on species abundance. For this, each sampling point (ordered by their geographic coordinates) was considered to be a sampling unit within each area38.

This approach was based on the application of the iNEXT (iNterpolation and EXTrapolation) package39, using the rarefaction (interpolation – number of species observed) and prediction curves (extrapolation – prediction derived from an increase in the number of sampling units) for the samples of occurrence, using the bootstrap method (considering 100 resamplings), which was not restricted only to the rare species, but estimated the total richness based on all the species sampled. The curves were compared based on the degree of overlap of the 95% confidence limits, which are standardized by the megahabitat with the smallest number of sampling units38,40. The median tests considered a critical significance level (α) of 5% and were run in the Vegan package41 of the R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computation), version 4.5.042.

Results

The analysis of the data revealed a total of 3286 species from 72,511 occurrence records between 1844 and 2024. Of this total, the bony fish were identified as the most diverse group, with 922 (28%) species, followed by 502 (15%) species of microorganisms, 464 (14%) species of molluscs (14%), and 312 (9%) corals species (9%). Considering the total number of species identified, 67 of them have a threat status classified as EN, VU or CR according to the list of threatened species of Brazil. The group with the highest number of threatened species is cartilaginous fish (40 species according to the IUCN or 27 considering the MMA red list), followed by bony fish, with 21 species.

Overall, considering all species, 22 are classified as Critically Endangered (CR) by the IUCN, and 17 by the MMA (Table 1), while 11 and 13 are classified as Endangered (EN), respectively. A further 44 species are classified as Vulnerable (VU) by the IUCN, and 37 by the MMA, and 18 and 31 species are listed as Near Threatened (NT), respectively. Of the remaining species, 44 are Data Deficient (DD) in the IUCN listing, while 2450 have not been evaluated (NE), and 697 are Least Concern (LC). In the MMA, 87 species are DD, 2518 are NE, and 583, LC.

The results of the ICMBio/CEPNOR monitoring added 1247 more species occurring in the ACS (39%) of the total data compiled in this study. Comparing the official databases with the final data compilation, the species records added by CEPNOR monitoring include 43% cartilaginous fish, 35% of the echinoderms, 27% of the molluscs, and 16% of the bony fish (Fig. 2).

The pie charts represent the proportion of the species identified in the present study. The cyan color represents the % of species present only in the official databases (combined datasets from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility - GBIF, Ocean Biodiversity Information System - OBIS, data obtained in major projects in the study area [e.g., JICA and REVIZEE], and the Marine Mammals Monitoring Support System - SIMMAM, the green color represents the % of species present only in the database of fisheries monitoring carried out by of the National Center for Research and Conservation of the Marine Biodiversity of Northern Brazil of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation - CEPNOR/ICMBio), and the yellow color represents the % of species present in both datasets. The bar chart indicates the individual percentage of each database.

The taxonomic group with the largest proportion of species for which the conservation status has been defined by the MMA (Fig. 3) is the seabirds (72.0% of the total), followed by cetaceans (69.2%), cartilaginous fish (65.6%), the turtles (62.5%), and bony fish (61.6%). By contrast, the groups with the fewest taxa evaluated are the algae, other invertebrates, other crustaceans, microorganisms, and worms, with a total of 593 species (Fig. 3).

Proportion of the species in the different taxonomic groups for which the conservation status has been evaluated. This analysis includes the records (collected between 1844 and 2024) identified from the scientific collections listed in official databases (i.e., the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS), the Marine Mammals Monitoring Support System (SIMMAM), the databases of other major projects that focused on the study area (i.e., the JICA and REVIZEE projects), as well as the official monitoring conducted by the National Center for Research and Conservation of the Marine Biodiversity of Northern Brazil (CEPNOR), part of the Chico Mendes Institute (ICMBio).

The vectorial analysis of the species impacted by fisheries (Fig. 4) indicate that the most threatened forms tend to be targeted by more than one fishery, irrespective of the type of fishing operation or regulatory measures. Extremely sensitive and endangered species, such as Ophidion holbrooki, Sphyrna tiburo, Eretmochelys imbricata, and Epinephelus itajara are impacted by at least three different fisheries simultaneously.

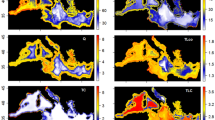

The species heat maps (Fig. 5) reveal an extensive area of distribution of species in general (A) and threatened species (B) in the area of the Amazon plume, as well as distinct hotspots of general biodiversity (C) off the coast of the state of Amapá, and of threatened species (D), off the coast of southern Amapá and Pará, including oil exploration sectors SFZA-AP2 (block FZA-M-539) and SFZA-AP4.

Considering all the biodiversity recorded in the present study, the principal concentration of species were identified off the coasts of Pará and Amapá, and over the Amazon reef system, with hotspots in or near the areas of the oil exploration sectors, in particular in sector SFZA-AP1 (blocks FZA-M57, 59, 86, 88, 90, 125, and 127) and in the vicinity of sector SFZA-AP4 (Fig. 6A). When only the threatened species are considered, the greatest species richness is found off the coast of Pará (Fig. 6B), with smaller hotspots in sector SFZA-AP2 (block FZA-M-539) and near sector SFZA-AP4.

Overall, 710 of the 3286 species identified in the present study were identified in more than one of the megahabitats of the ACS, although 426 species were recorded exclusively in the ARA, 374 in the ATR, and 81 in the AIP (Fig. 7a). While the AIP had the fewest exclusive records, it had the greatest species richness per sampling unit (Kruskal-Wallis test: H = 137.56; p < 0.001) in comparison with the other two megahabitats, however, Dunn’s post hoc test indicates that AIP has the greatest species richness compared to the other areas (AIP-ARA: p < 0,001, AIP-ATR: p < 0,001) and ARA-ATR: p < 0,001), with ARA having the lowest species richness (Fig. 7b). Some groups, such as the corals (69.4%), worms (59.5%), and other crustaceans (35.7%) were predominant in the ARA.

The rarefaction curve (Fig. 7c) indicates that the actual biodiversity of all three areas is likely much higher than that recorded here, as well as reconfirming the differences in the species richness observed here among the three megahabitats. The fact that all three curves fail to reach the asymptote in the bootstrap estimator indicates that the species richness recorded in the ARA represents only 58.5% of the estimated total, and only 56.7% in the ATR, and 37.22% in the AIP.

(a) Occurrence (%) of the marine species per megahabitat of the Amazon Continental Shelf off the mouth of the Amazon River, including their exclusive presence in one of the zones (AIP, ATR, ARA), and their combined presence in two or three megahabitats, (b) The mean species richness per sampling unit recorded in the three zones, showing that the AIP was significantly more speciose (H = 137.56; p < 0.001) than the other two zones. Different letters above any pair of means indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05), based on Dunn’s post hoc test, and (c) rarefaction curves for the three zones, indicating that the true biodiversity is likely to be much higher than that observed up to now, in all three cases.

Discussion

The species diversity of the ACS is clearly much greater than that indicated by the vast majority of the published literature18. The present study identified a total of 3286 taxa, ranging from minuscule crustaceans and other invertebrates to the megafauna, which contribute to a complex web of inter-relationships, which is clearly vulnerable to anthropogenic impacts26.

The lack of divulgation of some of the studies conducted in the region of the Amazon Continental Shelf (ACS), especially research conducted prior to the 1980s, has obscured a number of important discoveries that have only recently come to light43. One of these cases was the much-publicized “discovery” of the coral reef system off the mouth of the Amazon River by Moura et al.34, when in fact, the existence of this system had already been recognized in 1977 by Bruce B. Collette & Klaus Rützler44.

The first species inventory of the ACS was conducted between 1957 and 1969, and was organized by the National Marine Fisheries Service, part of NOAA45. This survey focused on the region’s most valuable commercial fishery resources, and thus registered a fauna of only 54 species, which was similar to the total recorded off the coast of French Guiana44.

Miloslavich et al.46 concluded that the most comprehensive inventory of the marine biodiversity of South America was compiled by the Marine Life Census program (Census 2002), through the sharing of information by a number of researchers, which was used to generate a regional OBIS database. This database was reinforced by additional records from other studies of commercial fisheries18,20,22,25,26,47,48, resulting in the identification of 2039 species from the study area acording to Census program.

These numbers are clearly underestimated, especially given that, in practice, many Brazilian researchers do not deposit their specimens in scientific collections to restrict the access of the public. According to Morrell49 this scientific protectionism is a historical process, observed since 1830, when a number of scientific academies were established in England. The author claimed that the unwillingness of researchers to cooperate in science in order to reinforce their power and personal vanity, together with the lack of a governmental science initiative, has contributed to the establishment of isolated groups of researchers that are not articulated systematically with the state or the need for the resolution of common problems.

This lack of cooperation has contributed to the dispersal of important data that could contribute to a better understanding of biodiversity21,43,50,51 and the development of more effective management measures22,52. In this context, the present study contributes 1247 new taxa to the list – some of which may appear in publications, but not in the official databases – bringing the total number of species identified in the ACS to 3286.

In the present study, the greatest occurrence of species in general and of threatened taxa in particular was observed in the area influenced directly by the plume of the Amazon River, followed by the areas surrounding the coral reef system (Fig. 6). This distribution pattern can be accounted for by the combined freshwater discharge of the Amazonas and Orinoco rivers53, as well as the migration routes of the juveniles and post-larvae, primarily of the trophic baseline crustaceans, which stretch between the coasts of Pará and Amapá54.

These species are impacted fundamentally by fisheries– in particular, the bottom trawlers that modify the whole environment55 – which are obviously the principal stressor and the greatest current problem for the achievement of sustainability26. Historically, some fisheries, such as those of the red snapper (Lutjanus purpureus) have been highly regulated, but even so, the species has become vulnerable, in the MMA Red Book classification, and continues to be exploited intensively, with fisheries adhering to regulations that may simply not guarantee the capacity of stocks to recover from fishing pressure22.

The principal challenge lies in the fact that, while these fisheries threaten the marine biodiversity, they provide more than 3500 jobs in the region, creating a market for more than 330 formal companies and 2796 small businesses, which generate more than US$82 million per annum, in exports alone24,56,57,58,59,60,61,62. These economic considerations provide potent arguments for the maintenance of these fisheries through state subsidies61.

The end result is that more than 60 of the species identified in the area are threatened with extinction considering the MMA classification (Table 1). This likely underestimates the actual scenario, especially in the case of the invertebrates17, which are often overlooked in conservation research, in favor of the more “charismatic” groups of organisms, which are targeted because of their appearance, perceived ecological importance or natural rarity63. These organisms tend to include the megafauna – seabirds, cetaceans, and turtles – and animals of commercial interest, such as bony and cartilaginous fish (Fig. 4). Brodie et al.64 concluded that the criteria established by the IUCN – and replicated by the MMA – for the compilation of red lists follow a fixed methodological approach which, when extrapolated to non-standard organisms, faces a series of limitations ranging from the availability of resources and logistics to cultural barriers. Given this, the assessment of the conservation status of an organism based on the IUCN criteria is more effective for groups with more comprehensive data, which in the context of the ACS, refer primarily to the organisms most impacted by fisheries65.

In fact, scientific and political interest in the marine biomes of the Amazon region has grown after the discovery of after the discovery of oil deposits in the ACS66. This established the need for the involvement of environmental organs, in particular IBAMA, which require adequate data on the potential impacts of oil exploration on the local biodiversity to develop effective strategies for the mitigation of these pressures28,29. In this context, it is no surprise that IBAMA has deferred licenses for oil exploration in the ACS so frequently27.

The Oil and Gas Observatory of the ARAYARA Foundation67 estimates that the restrictions on navigation related to oil exploration and production, which include the creation of safety zones and restricted navigation routes, will result in the complete exclusion of fishing vessels from an area of approximately 34,616 km2. This would have major economic impacts for the local communities that depend on fisheries, due not only to the reduction in the area of their fishing grounds, but also the rerouting of fishing vessels62.

The results of the present study also highlight other challenges related to the extraction of fossil fuels. The analysis of the distribution and concentration of local diversity, both in general and in terms of the threatened taxa, revealed a number of hotspots in the vicinity of the coast of the states of Amapá and Pará, and in oil exploration sectors SFZA-AP2 (block FZA-M-539) and SFZA-AP4. A hotspot was also identified in sector SFZA-AP1, whose operation is still under discussion (Fig. 5). This implies that the liberation of these sectors for oil exploration should have a direct impact on a significant portion of the local biological richness68.

Oil exploration and production may impact the environment, even without oil spills69. Surveying and drilling exploratory wells causes sound pollution, which has an immediate effect on local biodiversity, and may compromise the behavior of many animal species70. During the oil extraction, in addition to the degradation of the environment71, the eventual contamination of the water may spread over a wide area, with major repercussions for the local biodiversity72. Following the extraction of the oil, the use of the fossil fuels produced by the operations will contribute to global warming, which causes, for example, coral bleaching73,74.

No less important than the local impacts of oil extraction, the exploitation of fossil fuels contradicts the commitments made by Brazil and many other countries around the world toward the reduction of greenhouse gases and the mediation of global warming75,76. The ongoing deforestation in the Amazon region is also related to climate change, and has modified significantly the local hydrological regime77, resulting in prolonged dry periods and unprecedented droughts78. The effects of these changes on the fauna influenced by the discharge of the Amazon River65, which is responsible for 25% of primary global production, has yet to be fully understood8.

The results of the present study thus reveal the presence of a rich biodiversity in the ACS, which is potentially exposed to a new “anthropogenic web” that limits the full understanding of its biological configuration. This web extends from scientific protectionism – which has delayed the divulgation of important data – through intense fishing activity, which has often disrespected the fishery legislation and become predatory22, to oil exploration. This may not only affect the marine ecosystems – and compromise the conservation status of many species – but may also influence the provision of services by terrestrial ecosystems, affecting the cultural and economic dynamics of the local human populations79,80,81.

In this context, the discussion, regulation, and monitoring of fisheries must continue, not least because the number of species affected in the ACS is now likely to increase, given the new data on the region’s biodiversity presented here. In particular, continuous monitoring programs should not be interrupted, to ensure the accumulation of more reliable data on the dynamics, biodiversity, and resilience of this environment.

In addition to all these considerations, the findings of the present study provide important insights for the ongoing debate on oil exploration. This input contributes to the definition of the alternative, preventive, and corrective measures that should be applied to any activities related to the exploitation of oil deposits, in addition to compensatory actions, when appropriate, not only from an environmental perspective, but also from an economic and social viewpoint.

Conclusions

The CEPNOR/ICMBio monitoring program recorded more than a third of the 3286 species from the Amazon Continental Shelf identified in the present study. This reaffirms the value of continuous monitoring as a fundamental tool for the inventory of biodiversity, as well as emphasizing the importance of registering information in official databases, where it can be accessed as part of the development of management measures.

In the region of the Amazon Continental Shelf, the species are concentrated primarily within the area influenced directly by the Amazon plume, as well as along the margins of the Amazon reef system. A total of 67 of the species identified in the present study are listed as threatened in Brazil (MMA), while 77 are classified as threatened worldwide (IUCN). These numbers are likely an underestimate of the true level of threat to the region’s biodiversity, however, given that the assessment of conservation status tends to focus on the better known or economically more important species.

Many of these threatened species are targeted by more than one type of fishery operating in the ACS, which reinforces the conclusion that this economic activity is a major threat to the region’s biodiversity. The proposal for the creation of oil exploration sectors SFZA-AP2 (block FZA-M-539), SFZA-AP4, and SFZA-AP1 refers to areas that coincide with or are adjacent to the hotspots of biodiversity on the ACS observed in the present study, both in general, and in terms of the presence of threatened taxa.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to require institutional sanction from ICMBio but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The authors inform that they already have authorization to publish the data after complying with ICMBio’s institutional rules, the data will be entered into SISBBR.

References

DeMaster, D. J., Kuehl, S. A. & Nittrouer, C. A. Effects of suspended sediments on geochemical processes near the mouth of the Amazon river: examination of biological silica uptake and the fate of particle-reactive elements, Cont. Shelf Res. 6, 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4343(86)90056-7 (1986).

Ekau, W. & Knoppers, B. A review and re-definition of the Large Marine Ecosystems of Brazil, in: K. Sherman, G. Hempel (Eds.), Large Mar. Ecosyst. World -Trends Exploit. Prot. Res. LME, Elsevier Science, : pp. 355–372. (2003).

Prestes, Y. O., da Borba, T. A., da Silva, A. C. & Rollnic, M. A discharge stationary model for the Pará-Amazon estuarine system. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 28, 100668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2020.100668 (2020).

Dittmar, T. Outwelling of organic matter and nutrients from a Mangrove in North brazil: evidence from organic tracers and flux measurements, in: (1999). https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:126962337

Floriani, D. C., Fukuda, J. C. & Pinto, E. F. Parque Nacional Dos Lençóis maranhenses: o Maior Campo de Dunas Costeiras Da América do Sul. Rev. Gerenc Cos Integr. 1, 62–64 (2004).

Francini-Filho, R. B. et al. Perspectives on the great Amazon reef: extension, biodiversity, and threats. Front. Mar. Sci. 5 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00142 (2018).

Noriega, C. & Araujo, M. Carbon dioxide emissions from estuaries of Northern and Northeastern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 4, 6164. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06164 (2014).

Sharples, J., Middelburg, J. J., Fennel, K. & Jickells, T. D. What proportion of riverine nutrients reaches the open ocean? Global biogeochem. Cycles 31, 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GB005483 (2017).

Aquino, R. et al. Possible Amazonian contribution to Sargassum enhancement on the Amazon continental shelf, sci. Total Environ. 853, 158432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158432 (2022).

Richardson, P. L., Hufford, G. E., Limeburner, R. & Brown, W. S. North Brazil current Retroflection eddies. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 99, 5081–5093. https://doi.org/10.1029/93JC03486 (1994).

Costa, E. A. & Figueiredo, A. G. Echo-character and sedimentary processes on the Amazon continental shelf. Acad. Bras. Ciências. 70, 187–200 (1998).

Brunskill, G. J. & Margins, T. in Carbon Nutr. Fluxes Cont. Margins A Glob. Synth. 423–493 (eds Liu, L., Kon-Keeand & Atkinson) (Springer, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92735-8_8

Araujo, M., Noriega, C. & Lefèvre, N. Nutrients and carbon fluxes in the estuaries of major rivers flowing into the tropical Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 1 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2014.00010 (2014).

Prestes, Y. O., da Silva, A. C. & Jeandel, C. Amazon water lenses and the influence of the North Brazil current on the continental shelf, Cont. Shelf Res. 160, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2018.04.002 (2018).

Regnier, P. et al. Anthropogenic perturbation of the carbon fluxes from land to ocean. Nat. Geosci. 6, 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1830 (2013).

Marceniuk, A. P. Sharks and batoids (Subclass Elasmobranchii) caught in the industrial fisheries off the Brazilian North Coast. Rev. Nord Biol. 27 https://doi.org/10.22478/ufpb.2236-1480.2019v27n1.47112 (2020).

da Nóbrega, P. S. V., Meira dos Santos, C. R., Cordeiro, A. P. B. & Martinelli-Lemos, J. M. Invertebrates assemblage captured by a Pink shrimp’s fishery on Amazon continental shelf. Lat Am. J. Aquat. Res. 49, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.3856/vol49-issue2-fulltext-2600 (2021).

Marceniuk, A., Caires, R., Rotundo, M., Alcântara, R. & Wosiacki, W. The icthyofauna (Teleostei) of the Rio Caeté estuary, Northeast pará, brazil, with a species identification key from Northern Brazilian Coast. Panam. J. Aquat. Sci. 12, 31–79 (2017).

Brasil Plano de Recuperação do Pargo, Brasília, (2018).

Ferreira, B. P., Olavo, G. & França, A. R. Projeto REPENSAPESCA- Avaliação Ecossistêmica Dos Recursos Pesqueiros Demersais E Pelágicos Das Costas Norte E Nordeste (Subsídios para o Ordenamento Pesqueiro Sustentável, 2022).

de Klautau, A. G. C. et al. The deep sea teleost fish fauna of the Brazilian North Coast. Neotrop. Ichthyol. 18 https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-2020-0030 (2020).

de Klautau, A. G. C. et al. Da silva, regulation of the Caribbean red snapper fishery on the Amazon continental shelf: 60 years of conflict between conservation and exploitation. Mar. Policy. 174, 106622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2025.106622 (2025).

Frédou, F. L. et al. Aspectos econômicos Da Pesca industrial no pará: entraves e perspectivas (Paper 265), pap. Do NAEA. 1 https://doi.org/10.18542/papersnaea.v19i1.11361 (2010).

IBAMA & Estatística nacional da pesca (2007) 1–151. (2007).

da Silva, L. E. O., Silva, K. C. A. & Cintra, I. H. A. Sobre a Pesca industrial Para Peixes Diversos Na Plataforma continental Amazônica. Rev. Bras. Eng. Pesca. 7, 19 (2014). www.sumarios.org

de Klautau, A. G. C. et al. Impacted biodiversity by industrial Piramutaba fishing in the Amazon river mouth, Bol. Do Inst. Pesca. 42, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.20950/1678-2305.2016v42n1p102 (2016).

Neves, A. F. M., Zuffo, M. M. & Duleba, W. Novas demandas de cooperação internacional: análise das implicações diplomáticas da exploração de recursos na foz do Amazonas, in: Visões Para Um Mundo Sustentável Abordagens Em Ciência, Tecnol. Gestão Socioambiental e Governança, Editora Blucher, : pp. 116–139. (2024). https://doi.org/10.5151/9786555503487-06

IBAMA, Parecer Técnico n° 128/2023-Coexp/CGMac/Dilic. Atividade de Perfuração Marítima no bloco FZA-M-59, bacia da foz do Amazonas. (2023).

IBAMA, Decisão do Ibama sobre pedido de licença para perfuração no bloco FZA-M-59, na bacia da foz do Amazonas. (2023).

de Barros, D. et al. Effects of deforestation and other environmental variables on floodplain fish catch in the Amazon. Fish. Res. 230, 105643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105643 (2020).

Trindade, D. G. et al. Effects of marine climate variability on the relative abundance of < scp > Lutjanus purpureus (POEY, 1866) on the Amazon continental shelf. Fish. Oceanogr. 33 https://doi.org/10.1111/fog.12662 (2024).

Marceniuk, A. P. et al. Megahabitats shape fish distribution patterns on the Amazon Coast. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 305, 108847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2024.108847 (2024).

Brasil Instrução Normativa no 13, de 18 de setembro de Brazil, 2013. (2013). https://pesquisa.in.gov.br/imprensa/jsp/visualiza/index.jsp?data=19/09/2013&jornal=1&pagina=36&totalArquivos=88

Moura, R. L. et al. An extensive reef system at the Amazon river mouth. Sci. Adv. 2 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501252 (2016).

Bayma, A. P., Paixão, L. R. L. & Pompeu, M. S. Áreas prioritária para a Conservação, Utilização Sustentável e Repartição dos Benefícios da Biodiversidade, Brasília, (2023).

Falcon, G. B., Soares, A., Louzada, R. & Raíces, D. PRIM-PGMar - Plano De Redução De Impactos Das Atividades De Exploração E Produção De Petróleo E Gás (Natural sobre a Biodiversidade Marinha e Costeira, 2023).

Araujo, L. S. et al. Growing industrialization and poor conservation planning challenge natural resources’ management in the Amazon shelf off Brazil. Mar. Policy. 128 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104465 (2021).

Gotelli, N. J. & Colwell, R. K. Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol. Lett. 4, 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00230.x (2001).

Hsieh, T. C., Ma, K. H. & Chao, A. iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (< Scp > H ill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12613 (2016).

Chao, A. et al. Rarefaction and extrapolation with hill numbers: a framework for sampling and Estimation in species diversity studies. Ecol. Monogr. 84, 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0133.1 (2014).

Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0–2, (2019).

RCore & Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing, (2025).

Marceniuk, A. P. et al. De Macedo klautau, L. Montag, the bony fishes (Teleostei) caught by industrial trawlers off the Brazilian North coast, with insights into its conservation. Neotrop. Ichthyol. 17 https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-20180038 (2019).

Bruce, B. & Collette Klaus Rützler, Reef Fishes Over Sponge Bottom off the mouth of the amazon river, in: Proceedings, Third Int. Coral Reef Symp., : pp. 305–310. (1977).

Marceniuk, A. P., Caires, R. A., Carvalho-Filho, A. & Rotundo, M. M. W.C.R. Dos Santos, A.G.C. De Macedo Klautau, Peixes Teleósteos Da costa Norte Do Brasil (Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 2020).

Miloslavich, P. et al. Marine biodiversity in the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts of South america: knowledge and gaps. PLoS One. 6, e14631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014631 (2011).

Paiva, K. S., Aragão, J. A. N., Silva, K. C. A. & Cintra, I. H. A. Fauna Acompanhante Da Pesca industrial do Camarão-Rosa Na Plataforma continental Norte brasileira, Bol. Técnico Científico Do CEPNOR. 9, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.17080/1676-5664/btcc.v9n1p25-42 (2009).

Bentes, B. et al. Documento técnico sobre a Situação atual Das pescarias do Pargo Na Região Norte do Brasil, 132. (2017).

Morrell, J. B. Individualism and the structure of British science in 1830, Hist. Stud. Phys. Sci. 3, 183–204. https://doi.org/10.2307/27757318 (1971).

Caires, R. A. et al. The Tonkin weakfish, Cynoscion similis (Sciaenidae, Perciformes), an endemic species of the Amazonas-Orinoco Plume. Acta Amaz. 49, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4392201803481 (2019).

Rotundo, M. M., Machado, L., Oliveira, C., dos Santos, W. C. R. & Marceniuk, A. P. Record of the rare Caribbean mud eel, Pythonichthys sanguineus (Heterenchelyidae, Anguilliformes), in the region of the Amazon Reef. Acta Amaz. 49, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4392201802883 (2019).

Aragão, J. A. N. OEI Organização dos Estados Ibero-americanos Para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura, (2017).

Grodsky, S. A., Reverdin, G., Carton, J. A. & Coles, V. J. Year-to-year salinity changes in the Amazon plume: contrasting 2011 and 2012 aquarius/sacd and SMOS satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 140, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2013.08.033 (2014).

Peixoto, U. I., Mello-Filho, A. S., Bentes, B. & Isaac, V. J. Trawl fishing fleet operations used to illustrate the life cycle of the Southern brown shrimp: insights to management and sustainable fisheries. Fishes 7, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes7030141 (2022).

Olsgard, F., Schaanning, M. T., Widdicombe, S., Kendall, M. A. & Austen, M. C. Effects of bottom trawling on ecosystem functioning. J. Exp. Mar. Bio Ecol. 366, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2008.07.036 (2008).

Pinheiro, L. A. & Frédou, F. L. Caracterização Geral Da Pesca Industrial Desembarcada No Estado Do Pará, Rev (Virtual Iniciação Científica Da Univ. Fed. Do Pará, 2004).

Isaac, V. J. Explotação e Manejo Dos recursos Pesqueiros do litoral amazonico: Um Desafio Para o futuro. Ciência E Cult. 58, 33–36 (2006).

Isaac, V. J., Martins, A. S., Haimovici, M. & Andrigetto, J. M. A Pesca Marinha E Estuarina Do Brasil No Início Do Século XXI: Recursos, Tecnologias,aspectos Socioeconômicos E Institucionais (Universidade Federal do Para, 2006).

Castello, J. P. O futuro Da Pesca Da aquicultura Marinha no brasil: a Pesca Costeira. Cià E Cult. 62, 32–35 (2010). http://cienciaecultura.bvs.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext &pid=S0009-67252010000300013&nrm=iso.

Aragão, J. A. N. Documento técnico contendo o diagnóstico da pesca do pargo Lutjanus purpureus, englobando os aspectos ecossistêmicos, biológicos, pesqueiros, econômicos, sociais e legal da atividade., (2017).

Trindade, D. A. G., Fonseca, G. B. A. N., Freire, J. C. L., dos Santos, M. D. A. S. & Brabo, M. E. F. Artigos | Seção Cadeia de valor da pesca do pargo no município de Bragança, Estado do Pará, Amazônia, Brasil (2023). https://doi.org/10.12957/cdf.2023.71055

Fapespa, N. Técnica da Pesca Paraense (2023) 34. (2023).

McClenachan, L., Cooper, A. B., Carpenter, K. E. & Dulvy, N. K. Extinction risk and bottlenecks in the conservation of charismatic marine species. Conserv. Lett. 5, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00206.x (2012).

Brodie, J. et al. Red list for British seaweeds: evaluating the IUCN methodology for non-standard marine organisms. Biodivers. Conserv. 32, 3825–3843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-023-02649-0 (2023).

Marceniuk, A. P., Caires, R. A., Wosiacki, W. B. & Di Dario, F. Conhecimento e Conservação Dos Peixes Marinhos e estuarinos (Chondrichthyes e Teleostei) Da costa Norte do Brasil. Biota. Neotrop. 13, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032013000400022 (2013).

de Mahiques, M. M. et al. Insights on the evolution of the living great Amazon reef system, Equatorial West Atlantic. Sci. Rep. 9, 13699. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50245-6 (2019).

Nora, V., Carvalho, K., Mendes, G., de Oliveira, N. F. & de Araújo, J. B. Impactos do avanço do petróleo na pesca da costa amazônica, Brasília, (2024). https://marsempetroleo.arayara.org/pesca/

Banha, T. N. S. et al. Francini-Filho, the great Amazon reef system: A fact. Front. Mar. Sci. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.1088956 (2022).

Butt, N. et al. Biodiversity risks from fossil fuel extraction. Science 342, 425–426. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1237261 (2013).

Di Iorio, L. & Clark, C. W. Exposure to seismic survey alters blue Whale acoustic communication. Biol. Lett. 6, 51–54. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2009.0651 (2010).

O’Rourke, D. & Connolly, S. Just oil? The distribution of environmental and social impacts of oil production and consumption. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 28, 587–617. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.28.050302.105617 (2003).

Nnadi, V. E., Udokporo, E. L. & Okolo, O. J. Petroleum production activities and depletion of biodiversity: A case of oil spillage in the Niger Delta, in: Handb. Environ. Conscious Manuf., Springer International Publishing, Cham, : 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75834-9_9. (2022).

Goreau, T. J. F. & Hayes, R. L. Global warming triggers coral reef bleaching tipping point. Ambio 50, 1137–1140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01512-2 (2021).

Andini, N., Pratama, G., Ariyanti, I., EdelwisT.W. & Riel, B. Global warming threats to coral bleaching events and their impacts on coastal ecosystem sustainability. BIO Web Conf. 134, 02009. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/202413402009 (2024).

Cheung, W. W. L. et al. Projecting global marine biodiversity impacts under climate change scenarios. Fish. Fish. 10, 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00315.x (2009).

Yanik, T. & Aslan, I. Impact of global warming on aquatic animals. Pak J. Zool. 50 https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/2018.50.1.353.363 (2018).

Hilker, T. et al. Vegetation dynamics and rainfall sensitivity of the Amazon, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 16041–16046. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1404870111

Marques, B. L. B. & Pereira, J. W. The Contribution of Social Assistance Policy in Addressing the Drought in the Amazon from 2023 To 2024 (Universidade Federal do Amazonas - UFAM, 2024).

Laurance, W. F., Goosem, M. & Laurance, S. G. W. Impacts of roads and linear clearings on tropical forests. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 659–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.009 (2009).

Finer, M. & Orta-Martínez, M. A second hydrocarbon boom threatens the Peruvian amazon: trends, projections, and policy implications. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 014012. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/5/1/014012 (2010).

Parish, E. S. et al. Comparing scales of environmental effects from gasoline and ethanol production. Environ. Manage. 51, 307–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9983-6 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the onboard scientific observers of the CEPNOR/ICMBio monitoring program that worked so hard over the years to collect the data analyzed here. These young researchers demonstrated an extraordinary level of dedication to collect data on the marine biodiversity of the Amazon region, helping to reduce the knowledge gap that exists on the biological diversity of the northern coast of Brazil. We would also like to thank the team at CEPNOR/ICMBio, and the Federal Rural University of Amazonia and the Federal University of Pará for their respective inputs toward the development of the study presented here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G.C.M.K. wrote the main manuscript text, conceived the experiment(s), conducted the experiment(s), analysed the results. A.P.B.C. and B.B.S. conducted the experiment(s), analysed the results, reviewed the manuscript, R.A.C, A.P.M, W.C.R.S., conducted the experiment(s), analysed the results, prepared all figures and tables. N.S.S.C, C.E.M.C.B., F.A.A.J., I.H.A.C and L.C.P. reviewed the manuscript, P.S.V.N. and, J.M.M.L. identified the invertebrates.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Macedo Klautau, A.G.C., Cordeiro, A.P.B., das Chagas, R.A. et al. Biodiversity hotspots and threatened species under human influence in the Amazon continental shelf. Sci Rep 15, 26681 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11261-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11261-x