Abstract

Public attitudes vary across mental health (MH) problems. However, research on young people and certain MH conditions is limited. This online-experiment examined stigma and potential help-seeking among 554 adolescents and emerging adults aged 14–29 years towards generalized anxiety disorder, depression (DEP), bulimia nervosa (BN), non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), and problematic alcohol use (ALC). Participants were randomized to a video vignette depicting one of the five MH problems. Attitudes were measured with the Universal Stigma Scale (subscales: “blame/ personal responsibility” and “impairment/ distrust”) and the General Help Seeking Questionnaire assessing the likelihoods of seeking professional, informal, and no help for the respective MH problem. Data were analysed using Kruskal-Wallis and Bonferroni-corrected Dunn’s tests. Compared to all of the other conditions, ALC was the most stigmatized. Furthermore, ALC was more likely to prompt any help-seeking as compared to DEP, BN, and NSSI, and professional help-seeking in comparison to DEP. BN elicited more blame than DEP, whereas the reverse pattern emerged for distrust. However, this sample generally held positive MH attitudes. The results highlight the importance of addressing disorder-specific stigma and may inform the development of targeted anti-stigma and help-seeking campaigns.

Trial registration: This study has been registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (www.drks.de) on September 23rd, 2020 https//drks.de/search/de/trial/DRKS00023110 #DRKS00023110.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With at least 10% of children and adolescents1,2 and 25–39% of college students3,4 affected by common mental health (MH) problems such as anxiety and depression, MH problems in youth are increasingly prevalent and pose high burdens on both individuals and societies5,6. Approximately half of all mental disorders first develop by the age of 18 years7 and they frequently persist into adulthood8. While effective treatment exists, large proportions of young people either do not seek any support or receive treatment after substantial delays9,10, resulting in an alarming rate of unmet MH care needs of almost 60%11. Attitudinal barriers such as stigmatizing beliefs and a low MH literacy12,13,14 largely contribute to delayed help-seeking and treatment uptake. Previous literature has identified various aspects of stigma, manifesting on systemic, behavioural, and attitudinal levels as stereotypes and prejudice (i.e. beliefs or cognitive responses that associate undesirable characteristics with MH problems) as well as discrimination (i.e. social avoidance, distancing, and exclusion on interpersonal and structural levels)15. While public stigma in particular encompasses this variety of behavioural, systemic, affective, and cognitive aspects as well, on an attitudinal level, it refers to the agreement with negative stereotypes of the general population towards individuals with MH conditions16. While personal attitudes towards MH problems have previously also been termed “personal stigma” as opposed to “perceived (public) stigma”, i.e. the awareness of public stigma in the general population17, the term “public stigma” is used in the following to maintain consistency. A deeper understanding of these attitudinal barriers and the development of effective strategies to overcome them constitute major public health objectives15.

While stigmatizing beliefs affect MH problems in general, previous studies have identified differences in stigma across specific MH problems. These studies frequently utilized case vignettes, i.e. diagnostic descriptions of individuals affected by selected sets of symptoms, which provide more nuanced stimuli as compared to simple labels and can be used in experimental contexts via random assignment18. For instance, a representative Swiss vignette survey with an adult sample demonstrated that alcohol dependency symptoms and other-endangering behaviours increased the perceived dangerousness (i.e. perceptions of unpredictability and violence) of vignette characters19. A similar pattern was found in a study with Australian adolescents, wherein a vignette peer who displayed alcohol misuse was perceived as both more dangerous and as “weak” rather than sick in comparison to a depressed vignette character20. Both stigma dimensions, dangerousness and the “weak-not-sick” facet, were associated with weaker intentions to encourage informal help-seeking (e.g. consulting friends or family members), while dangerousness was associated with stronger intentions to recommend formal help-seeking (e.g. consulting MH professionals). Other studies compared stigmatizing attitudes among college students towards vignette characters depicting either obesity, eating disorders, or depression. While characters with obesity were blamed (i.e. held responsible) more strongly for their condition than characters with eating disorders, which in turn were blamed more than characters with depression, depression was associated with higher perceived impairment and distrust21,22. However, most studies addressed adult samples and a limited amount of MH problems, such as general MH, depression, schizophrenia18,23,24 or attention deficit disorder in the field of children and adolescents25. Youth samples and other MH problems such as eating disorders are less represented. As previous studies suggest differences in stigmatizing attitudes in relation to age26,27, gaining a deeper understanding of stigma in different phases of life is crucial for the development of targeted anti-stigma interventions.

Current study

This secondary analysis of an online-experiment examined and compared public stigma (other-oriented) and potential help-seeking (self-oriented) among adolescents and emerging adults aged 14 to 29 years between five MH problems, namely generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), depression (DEP), bulimia nervosa (BN), non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), and problematic alcohol use (ALC), expanding previous research by including MH conditions that have been less studied in young people. This study followed an exploratory approach and did not test specific hypotheses.

Methods

Study design

This study is based on a secondary analysis of data from a larger online-experiment with 15 conditions in total (5 MH problems × 3 interventional conditions). The primary study compared the effects of two video-based micro-interventions against a vignette-only control group (see Lemmer et al. (2024)28 for detailed information). While the two intervention groups were presented with an additional video aiming to either induce positive outcome-expectancies of help-seeking or to provide psychoeducational and destigmatizing information, only the vignette video which is described in more detail below was shown to the control group. Group allocation was implemented through an automated permuted block randomization (block sizes: 15, 30), stratified by gender. Participants who identified as men/ boys were presented with a male protagonist (“Paul”), while participants who identified as women/ girls and participants with another gender identity viewed a female protagonist (“Paula”). The current study uses only data from the five control conditions to ensure comparability, as differential intervention effects were found across MH conditions in the primary study. Allocation to the five groups was randomized.

Recruitment and sample

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee I of the Heidelberg Medical Faculty on 27th of July, 2020, protocol number S-378/2020. Adolescents and emerging adults aged 14 to 29 years with sufficient German language skills were recruited between October 2020 and May 2022. The age limit of 14 years was selected due to its widely accepted adequacy for the provision of informed consent in health-related decisions and study participation29,30 while the upper age limit of 29 years conforms with the age span of emerging adulthood, a distinct life stage between adolescence and established adulthood31,32. A convenience sample was primarily recruited online via social media, mailing lists, online forums, and online market places targeted at youths (e.g. online groups, accounts, and mailing lists of youth clubs or student associations). In an optional gift card lottery at the end of the study, participants had the chance to win one of 100 gift cards à 20 €. Participants who voluntarily provided their e-mail addresses at the end of the survey were eligible for the lottery. E-mail addresses were stored separately from other participant data to ensure anonymity.

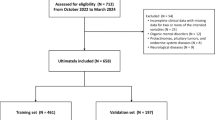

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants. In total, 730 participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were randomized to one of the five control conditions. Participants who did not complete data assessment (n = 103) and participants whose duration of stay on the video page fell below the length of the respective video they were assigned to watch, as indicated by page change timestamps, were excluded (n = 73). The final sample included N = 554 young persons (75.89%).

nrand. = randomized cases: number of randomized control group cases, irrespective of data completeness and video page duration of stay; nincl. = included cases: number of control group cases with complete data and sufficient durations of stay on the video vignette page which were included in the data analysis.

Procedure

This web-based experiment was implemented in the software ASMO33. It was openly accessible via a website containing the study information. Participants received extensive information about the study aims, procedures, data processing, and data storage prior to their participation. However, the information did not specify the five MH problems of the study. Instead, the general term “health problems” was used to avoid self-selection biases. After providing informed consent through an online checkbox, participants were presented with sociodemographic and screening questionnaires, watched the randomly assigned video, completed outcome questionnaires, and received MH emergency contact information on a debriefing page. Once the participants had confirmed their responses through a click on the “next”-button, they were not able to change the responses. There was no “back”-button. All items had to be completed in order to proceed with the study. In total, this study took participants approximately 30 min to complete. The study was conducted in German.

Measures

Sociodemographics and screening

All measures were self-reported assessments used to describe the characteristics of the sample. The sociodemographic form included questions about the participants’ age, gender, migration background, education, exposure to someone affected by MH problems (one item: “Do you know someone who has a mental illness? Similar terms are mental health problems, emotional problems, psychological issues, mental disorders, and personal difficulties.”), and their personal MH service use (past or current actual help-seeking).

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)34 was used to assess anxiety symptoms (current sample Cronbach’s α = 0.88; McDonald’s ω = 0.88). Across its seven items, symptom frequencies were measured on a 4-point response scale. Sum scores ≥ 5 indicate mild, ≥ 10 moderate, and ≥ 15 severe anxiety symptoms (potential range: 0–21)31.

The 9-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)35 was used to measure depression symptoms (current sample Cronbach’s α = 0.88; McDonald’s ω = 0.88). Symptom frequencies within the past two weeks were indicated on a 4-point scale. Sum scores ≥ 5 are interpreted as mild, ≥ 10 as moderate, ≥ 15 as moderately severe, and ≥ 20 as severe depressive symptomatology (potential range: 0–27)35.

The Weight Concerns Scale (WCS)36,37 is a five item questionnaire measuring weight and body shape concerns (current sample Cronbach’s α = 0.86; McDonald’s ω = 0.87). Scores ≥ 57 indicate an elevated risk for eating disorders (potential range: 0–100)36.

To assess NSSI, four items of the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI-G)38 were used (lifetime NSSI, frequency of NSSI within the last year, ages of first and last NSSI).

The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C)39,40 screened for problematic alcohol use during the past 12 months. It consists of three items with 5-point scales (current sample Cronbach’s α = 0.72; McDonald’s ω = 0.77). A sum score of 0 indicates abstinence, scores between 1 and 3 are indicative of moderate alcohol consumption, and scores ≥ 4 are interpreted as hazardous alcohol consumption (potential range: 0–12)39,41.

Outcomes

The Universal Stigma Scale (USS)21 with its subscales blame/ personal responsibility (5 items; current sample Cronbach’s α = 0.75; McDonald’s ω = 0.76; example item “Paula could pull herself together if she wanted to”) and impairment/ distrust (6 items; current sample Cronbach’s α = 0.77; McDonald’s ω = 0.77; example item: “People with a problem like Paul’s are dangerous”) was applied to assess stigmatizing attitudes towards the five MH problems on a 5-point Likert scale. For each of the two subscales, means were calculated. Lower scores indicate higher stigmatization.

A 12-item version of the General Help Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) was used to assess the potential use of formal, informal, and no support (i.e., the hypothetical willingness to seek help if participants themselves were affected by the MH problem assigned to them) within the next four weeks42. The GHSQ assesses the likelihood of seeking different sources of help for a previously defined problem on a 7-point rating scale (1 = “extremely unlikely”, 7 = “extremely likely”). The participants were thus asked about their likelihoods of approaching different sources of help if they themselves were experiencing the vignette character’s problem. Help-seeking was operationalized by the maximum scores of the items representing professional (psychotherapist, psychiatrist, counselling service) and informal (friend, parent, other family member, romantic partner) sources of MH support. No intention of seeking any help was measured with one GHSQ-item (“I would not seek any help”).

Video acceptability was measured with three translated items from the acceptability/ likability scale used by Gaudiano, Davis, Miller, and Uebelacker (2020)43 to assess overall likability, comprehensibility, and interestingness on a 5-point rating scale (1 = “not at all”, 5 = “very”).

Experimental conditions and materials

The experimental conditions were implemented with brief animated videos depicting case vignettes for each of the five MH problems. The vignettes were similarly structured across MH problems. First, the protagonists were introduced as 16-year old high school students in a third-person perspective. The videos then described challenges in their everyday lives due to their respective MH condition (e.g. difficult emotions and cognitions, social and school-related issues, physical symptoms). The vignettes were fully descriptive and did not include any diagnostic labels44. The BN vignettes were developed first and served as a template for the other four MH problems. The vignettes were inspired by Mond et al. (2010)45 and adapted in accordance with ICD-10 and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria as well as further literature on the respective symptomatology and psychological distress (e.g. DeJong et al., 201246). Each study site developed a vignette for a MH problem that was aligned with their respective area of expertise.

Vignette durations ranged from 02:19 to 02:47 min (M = 02:29, SD = 0:11). We used the online animation tool Powtoon Pro + to create the videos. A convenience sample of N = 9 youths (Mage = 18.56, SD = 3.74, range: 14–24 years, 1/3 male) pre-tested a subset of the videos between July and September 2020 and confirmed their overall acceptability and comprehensibility.

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic, screening, and outcome data were first analysed descriptively. Kruskal-Wallis (KW) and chi squared tests were performed to check for group differences in the screening and video acceptability measures. Due to non-normal distributions, KW tests were conducted to test group differences between the experimental conditions (MH problems) on the primary (stigma) and secondary outcomes (potential help-seeking). Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were further conducted to control for actual help-seeking, the gender of the vignette character (fixed factors), and age (covariate). However, as the ANCOVAs yielded similar results to the KW tests and the main outcome data distributions were strongly deviating from normality, indicating a better suitability of nonparametric approaches47only the KW test results are reported. Bonferroni-corrected Dunn’s post-hoc tests between experimental conditions were conducted whenever significant (p < 0.05) group main effects in the KW tests were found. η²H Effect sizes are reported for the KW tests48. For the post-hoc comparisons, r coefficients were calculated as effect sizes (common cutoff-points: r = 0.10 for small, r = 0.30 for medium, r = 0.50 for large effects)49,50. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 28 and R 4.3.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Sample characteristics

The participants’ age ranged between 14 and 29 years (M = 20.86, SD = 3.60). In total, 79.06% of the sample identified as women/ girls and 44.40% reported that they had sought professional help for a MH problem. Sociodemographic and screening results are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. Separate sample characteristics for each of the five vignette groups are shown in Supplementary Tables S1 to S5. On average, participants reported mild to moderate depression symptoms (PHQ-9: M = 9.76, SD = 6.16) and mild anxiety symptoms (GAD-7: M = 8.60, SD = 5.06). An elevated eating disorder risk was found in 19% of the sample, while hazardous alcohol consumption affected 31%. Lifetime and 12-month prevalences of NSSI amounted to 37% and 20%, respectively.

Video acceptability

On 5-point scales, the videos were, on average, rated as very comprehensible (M = 4.79, SD = 0.50), and moderately to highly likeable (M = 3.85, SD = 0.78) and interesting (M = 3.84, SD = 0.93). Most participants (n = 395, 71.30%) rated the general likability with a “4” or “5”, while only 26 individuals (4.69%) gave a rating of “1” or “2”. Almost all participants (n = 542, 97.83%) rated the comprehensibility with a score of “4” or “5”, with a minority of n = 5 (0.90%) participants assigning a score of “1” or “2”. Interestingness was rated with a “4” or “5” by n = 385 (69.49%) participants and with a “1” or “2” in n = 46 (8.30%) cases.

As indicated by KW and chi-squared tests prior to the main analysis, the groups did not differ significantly with regard to video acceptability (general likability: H(4) = 6.36, p = 0.17; comprehensiveness: H(4) = 8.42, p = 0.078; interestingness: H(4) = 6.37, p = 0.17) and all but one of the screening measures (age: H(4) = 2.07, p = 0.72; GAD-7: H(4) = 2.62, p = 0.62; PHQ-9: H(4) = 3.93, p = 0.42; WCS: H(4) = 2.12, p = 0.71; number of NSSI events during the past year: H(4) = 8.05, p = 0.090; AUDIT-C: H(4) = 1.48, p = 0.83; gender of the vignette characters: χ²(4) = 0.62, p = 0.96; dichotomized actual help-seeking: χ²(4) = 4.06, p = 0.40). The proportions of participants reporting lifetime NSSI differed significantly between the NSSI (n = 30, 26.79%) and the DEP groups (n = 52, 46.85%; χ²(4) = 10.85, p = 0.028; Bonferroni corrected pairwise post-hoc proportion test: χ²(4) = 9.65, p = 0.019). As two-factorial Puri and Sen tests (i.e. generalized KW tests51) which included lifetime NSSI as a second factor yielded similar results as the one-factorial KW tests, and none of the interaction effects with the MH problems were statistically significant, the one-factorial KW test results are reported. However, comparisons between the DEP and the NSSI groups should be interpreted with caution, as the significantly lower rate of individuals reporting lifetime NSSI yields contextual relevance in addition to its statistical impact.

Differences between MH problems

Descriptive and KW outcome results are displayed in Table 3.

Stigma (USS)

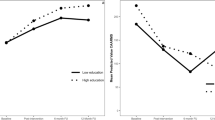

In the USS-subscale blame/ personal responsibility, the KW test revealed a statistically significant group main effect (H(4) = 67.60, p < 0.001, η²H = 0.12). Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests demonstrated a clear pattern where blame/ personal responsibility scores were significantly lower (i.e. agreement with stigmatizing statements was higher) in the ALC group as compared to any of the other conditions (GAD: z = 6.31, p < 0.001, r = 0.42; DEP: z = 7.54, p < 0.001, r = 0.50; BN: z = 4.28, p < 0.001, r = 0.29; NSSI: z = 5.64, p < 0.001, r = 0.38). Furthermore, participants in the DEP condition reported higher scores (i.e. less blame) than participants in the BN condition (z = 3.20, p = 0.014, r = 0.22).

With regard to the USS-subscale impairment/ distrust, a statistically significant group main effect was found (H(4) = 134.81, p < 0.001, η²H = 0.24). According to the post-hoc comparisons, the mean impairment/ distrust score was significantly higher (i.e. self-reported distrust was lower) in the BN group as compared to the DEP group (z = 4.05, p = 0.001, r = 0.27). Moreover, impairment/ distrust scores were significantly lower (i.e. distrust was higher) in the ALC group compared to all of the other conditions (GAD: z = 8.73, p < 0.001, r = 0.58; DEP: z = 6.69, p < 0.001, r = 0.45; BN: z = 10.71, p < 0.001, r = 0.72; NSSI: z = 8.18, p < 0.001, r = 0.55).

Help-seeking (GHSQ)

99 participants (17.87%) indicated a low likelihood of seeking professional help (scores of “1” or “2”), whereas n = 216 participants (38.99%) reported a high willingness to seek professional support (scores of “6” or “7”). Potential professional help-seeking differed between the conditions (H(4) = 11.03, p = 0.026, η²H = 0.013). Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant mean difference between the ALC and the DEP groups (z = 3.10, p = 0.019, r = 0.21).

Few participants (n = 20, 3.61%) reported a low likelihood of seeking informal help (scores of “1” or “2”), while the majority of the sample (n = 385, 69.49%) selected scores of “6” or “7”, with significant differences between the five conditions (H(4) = 9.80, p = 0.044, η²H = 0.011). None of the pairwise comparisons were statistically significant. Excluding the n = 5 cases with a comprehensibility score of less than 3 yielded similar results. Only the group effect for informal help no longer reached statistical significance (H(4) = 9.04, p = 0.060, η²H = 0.0093).

While n = 264 participants (47.65%) reported a low likelihood of not seeking any support (scores of “1” or “2”), n = 89 participants (16.06%) selected a score of “6” or “7”. Mean scores for no intention to seek any help differed significantly between the MH conditions (H(4) = 18.32, p = 0.001, η²H = 0.026). Scores in the ALC group (M = 2.39, SD = 1.68) were significantly lower in comparison to the DEP (z = 3.89, p = 0.001, r = 0.26), BN (z = 3.37, p = 0.007, r = 0.23), and NSSI groups (z = 2.82, p = 0.049, r = 0.19).

Discussion

Principal findings

This study compared stigmatizing and help-seeking related attitudes towards five MH problems in a sample of N = 554 adolescents and emerging adults aged 14 to 29 years. In comparison to the other four MH problems, ALC clearly stands out. While ALC emerged as the most stigmatized MH problem on both public stigma dimensions (blame/ personal responsibility and impairment/ distrust), it was also associated with a higher likelihood of potentially seeking professional support as compared to DEP. Moreover, the likelihood of not seeking any support was significantly lower for ALC than for DEP, BN, and NSSI. With respect to public stigma, the results are in line with previous research demonstrating the particularly pronounced and distinct stigmatization of and discrimination against individuals with alcohol use disorder in comparison to other substance-unrelated MH problems52,53. However, given the well-recognized detrimental impact of stigma on help-seeking14, the higher likelihoods of seeking any help and professional support for ALC in particular are surprising at first glance, even though relationships between stigma and help-seeking were not investigated in this study. On the other hand, a review by Hammarlund et al. (2018)54 demonstrated mixed effects of stigma on treatment-seeking decisions in alcohol- and drug-use disorders, with some studies identifying stigma as a positive predictor of help-seeking, while others found it to be a relevant barrier or observed no substantial impact. The authors argue that both the specific constructs measured, ranging from self-stigmatization to experiences of discrimination, as well as the target samples (e.g. participants with or without prior help-seeking experiences) varied considerably in this field of research, which may have contributed to heterogeneous results. The specificities of our study regarding its cross-sectional experimental design, its measures (public stigma towards others, potential help-seeking relating to oneself), and its sample composition should undoubtedly be taken into account in the interpretation of its results. Indeed, in a similar study, alcohol misuse was perceived as more dangerous than depression among a sample of high school students, with dangerousness positively predicting intentions to encourage formal help-seeking to an affected vignette peer20. Even though the current study measured a different facet of help-seeking (self-related instead of other-related) and investigated differences in the perception of MH problems instead of associations between stigma and help-seeking, limiting the comparability with the aforementioned study, these findings are in line with our results and might indicate a greater publicly perceived urgency of help-seeking in ALC due to the pronounced perception of dangerousness, but may not be applicable to other contexts, as we further discuss in the limitations section below.

While a significant overall group effect was found on the likelihood of seeking informal support, none of the post-hoc comparisons reached statistical significance. As the likelihood of seeking informal help was high across MH problems (all means reached a score above 5 on a 7-point scale), this result might suggest minimal overall differences which may not have been detected in the pairwise comparisons due to a low variability. Moreover, after the exclusion of n = 5 participants who indicated a poor comprehensibility of the vignettes, the group effect no longer reached statistical significance. While these results do not allow for specific conclusions about the MH problems included in this study, they confirm previous findings showing the importance of and preference for informal help in youths55,56,57. This emphasizes the potential of informal sources of support to either facilitate or obstruct treatment-seeking for MH problems58. As peer-led MH interventions have been shown effective in the promotion of adolescents’ help-seeking intentions12 and MH literacy was positively associated with peer-recommendations for formal help in previous research59, a deeper understanding of attitudes towards informal help-seeking for specific MH problems as well as the development and dissemination of targeted psychoeducational interventions for informal supporters could be essential steps in reducing the MH treatment gap.

Additionally, more blame and personal responsibility was reported for BN in comparison to DEP, while the opposite pattern was observed in the impairment/ distrust subscale of the USS, supporting previous findings of inverse associations between these public stigma dimensions in eating disorders and DEP21,22. As Ebneter and Latner (2013)21 and Thörel et al. (2021)22 argue, these results may suggest an underestimated public perception of the severity of eating disorders such as BN, resulting in stronger attributions of personal responsibility. Furthermore, the behavioural aspects of eating disorders as opposed to more internalizing MH conditions such as DEP may be associated with higher perceptions of voluntariness, control, and a lack of self-discipline21. Conversely, an increased awareness of the severity of depression may involve stronger perceptions of distrust and, in turn, a greater inclination towards social distance. However, as our results demonstrate, this association may be limited to specific MH conditions, whereas both facets of public stigma may be similarly pronounced towards other MH problems such as ALC. This further underscores the importance of understanding and addressing MH problem specific stigmata, which this experimental study is contributing to by involving a range of different and partly understudied MH problems.

As this study aimed to investigate public stigma and potential help-seeking in a general sample of adolescents and emerging adults, it should be noted that the vignettes and measures related to them were hypothetical. They were not necessarily related to the lived experiences of the participants as we did not aim to recruit a clinical sample. As previous research has shown that adolescents are both more likely to recommend formal help to peers than seeking help for themselves59 and to exhibit less public stigma in comparison to self-stigma60, suggesting differences in stigmatizing perceptions of oneself and others, the results of this study may not be applicable to, for instance, clinical samples experiencing stigmata related to the MH problems they are personally affected by. While the inclusion of a measure assessing potential help-seeking from the participants’ perspective served as an approximation of help-seeking intentions in a non-clinical sample, a help-recommendation measure could have been a valuable addition as it would have aligned more closely with the participants’ viewpoints as well as the public stigma measures. By acknowledging these different perspectives, future research that assesses and compares them may lead to a more comprehensive understanding of help-seeking and stigma.

Moreover, attitudes and intentions are not always accurate predictors of actual behaviour (intention-behaviour gap)61 which has been observed in treatment-seeking for MH problems as well. For instance, help-seeking intentions did not significantly predict actual help-seeking at a three-year follow-up in a Swiss sample of 16- to 40-year olds with MH problems, even though a small significant correlation was found62. While approximately 85% of the sample initially stated an intention to seek professional help, only 20% reported actual help-seeking62. Furthermore, only anticipated stigma (i.e. expected embarrassment if friends were to find out about the utilization of MH services) was negatively associated with actual help-seeking, whereas no direct significant impacts were found from personal (i.e. willingness to interact with depressed or schizophrenic patients) or perceived stigma (i.e. perceptions of public opinions about MH problems), highlighting once again that close attention should be paid to specific constructs and contexts of MH stigma research. As the aim of the current study was to investigate public stigma and hypothetical help-seeking intentions, the applicability of our findings may not generalize beyond these constructs.

Limitations

As mentioned above, the design, target sample, and actual sample composition of this study limit its applicability to other contexts. Even though we aimed to recruit a young community sample, participants generally reported low stigma and a high educational status. Furthermore, the sample included a relatively high proportion of severely distressed individuals (e.g. 8% reported severe depression symptoms as compared to approximately 2% in other studies with university students63), high rates of past or current help-seeking (45%), and comparably few participants identifying as men or boys (18%), which limits the generalizability of our results. As this study was openly accessible, resulting in self-selection into the study, it is plausible that young individuals with an elevated interest in MH were more inclined to participate, even though the general term “health issues” was used in the instructions instead of “MH problems” and we were careful not to specifically recruit psychology or medicine students. The sample characteristics observed in this study appear to be typical for openly accessible MH-related studies using social media as a primary recruitment channel. For instance, Lee et al. (2020)64 observed an overrepresentation of female, highly educated, and psychologically distressed participants who were recruited via Facebook advertisements for their suicide prevention study, which is consistent with our results. However, the use of targeted advertisements for men resulted in higher proportions of male participants, suggesting that adaptive recruitment strategies could be used in future studies to recruit more representative samples.

One further limitation of our study lies within the absence of a comprehension check to assure that the participants fully engaged with and understood the contents of the vignettes. Even though the durations of stay on the video pages were taken into account in the data analysis and the videos were rated as highly comprehensible (M = 4.79 on a 5-point scale), it remains unknown to what extent the participants truly attended to and comprehended the vignettes. To enhance the robustness of the findings, similar studies should include comprehension checks.

Conclusions

The results add to previous findings on differences in public stigma across MH conditions in adolescents and emerging adults and highlight the particular stigmatization of ALC as compared to GAD, DEP, BN, and NSSI. Furthermore, BN vignettes were blamed more for their condition than DEP vignettes, while the opposite pattern was observed with respect to perceived impairment and distrust. At the same time, potential help-seeking was more likely for ALC than other MH problems, suggesting that higher public stigma may not act as a barrier to help-seeking in all contexts. The results contribute to a broader understanding of specific attitudes towards different MH conditions and can help develop and optimize targeted anti-stigma and help-seeking campaigns.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALC:

-

Problematic alcohol use

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- AUDIT-C:

-

Alcohol use disorders identification test – alcohol consumption questions

- BN:

-

Bulimia nervosa

- DEP:

-

Depression

- GAD:

-

Generalized anxiety disorder

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized anxiety disorder scale-7

- GHSQ:

-

General help-seeking questionnaire

- KW:

-

Kruskal-Wallis

- MH:

-

Mental health

- NSSI:

-

Non-suicidal self-injury

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient health questionnaire-9

- SITBI-G:

-

Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview – German version

- USS:

-

Universal stigma scale

- WCS:

-

Weight concerns scale

References

Kieling, C. et al. Worldwide prevalence and disability from mental disorders across childhood and adolescence: evidence from the global burden of disease study. JAMA Psychiatry. 81, 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5051 (2024).

Sacco, R., Camilleri, N., Eberhardt, J., Umla-Runge, K. & Newbury-Birch, D. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in Europe. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02131-2 (2022).

Li, W., Zhao, Z., Chen, D., Peng, Y. & Lu, Z. Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 63, 1222–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13606 (2022).

Sheldon, E. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in university undergraduate students: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 287, 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.054 (2021).

Castelpietra, G. et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in europe, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Reg. Health Europe. 16 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100341 (2022).

McGorry, P. D. et al. The lancet psychiatry commission on youth mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 11, 731–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(24)00163-9 (2024).

Solmi, M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry. 27, 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7 (2022).

Mulraney, M. et al. A systematic review of the persistence of childhood mental health problems into adulthood. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 129, 182–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.07.030 (2021).

Scott, J. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of delayed help-seeking, delayed diagnosis and duration of untreated illness in bipolar disorders. Acta Psychiatry. Scand. 146, 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13490 (2022).

Wang, P. S. et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet 370, 841–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7 (2007).

Ghafari, M., Nadi, T., Bahadivand-Chegini, S. & Doosti-Irani, A. Global prevalence of unmet need for mental health care among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 36, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2021.10.008 (2022).

Aguirre Velasco, A., Cruz, I. S. S., Billings, J., Jimenez, M. & Rowe, S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0 (2020).

Cavelti, M. et al. An examination of sociodemographic and clinical factors influencing help-seeking attitudes and behaviors among adolescents with mental health problems. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-024-02568-7 (2024).

Radez, J. et al. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 30, 183–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4 (2021).

Thornicroft, G. et al. The lancet commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. Lancet 400, 1438–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01470-2 (2022).

Corrigan, P. W. & Watson, A. C. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 1, 16–20 (2002).

Griffiths, K. M., Christensen, H., Jorm, A. F., Evans, K. & Groves, C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 185, 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.185.4.342 (2004).

Angermeyer, M. C. & Schomerus, G. State of the Art of population-based attitude research on mental health: a systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatric Sci. 26, 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000627 (2017).

Sowislo, J. F., Gonet-Wirz, F., Borgwardt, S., Lang, U. E. & Huber, C. G. Perceived dangerousness as related to psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric service Use – a vignette based representative population survey. Sci. Rep. 7 https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45716 (2017).

Cheetham, A. et al. Stigmatising attitudes towards depression and alcohol misuse in young people: relationships with Help-Seeking intentions and behavior. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 9, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.2174/2210676608666180913130616 (2019).

Ebneter, D. S. & Latner, J. D. Stigmatizing attitudes differ across mental health disorders: a comparison of stigma across eating disorders, obesity, and major depressive disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 201, 281–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e318288e23f (2013).

Thörel, N., Thörel, E. & Tuschen-Caffier, B. Differential stigmatization in the context of eating disorders: less blame might come at the price of greater social rejection. Stigma Health. 6, 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000274 (2021).

Evans-Lacko, S. et al. The state of the Art in European research on reducing social exclusion and stigma related to mental health: A systematic mapping of the literature. Eur. Psychiatry. 29, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.02.007 (2014).

Peter, L. J. et al. Continuum beliefs and mental illness stigma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of correlation and intervention studies. Psychol. Med. 51, 716–726. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000854 (2021).

Kaushik, A., Kostaki, E. & Kyriakopoulos, M. The stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 243, 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.042 (2016).

Bradbury, A., Mental Health & Stigma The impact of age and gender on attitudes. Commun. Ment. Health J. 56, 933–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00559-x (2020).

Mackenzie, C. S., Heath, P. J., Vogel, D. L. & Chekay, R. Age differences in public stigma, self-stigma, and attitudes toward seeking help: A moderated mediation model. J. Clin. Psychol. 75, 2259–2272. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22845 (2019).

Lemmer, D. et al. The impact of Video-Based microinterventions on attitudes toward mental health and help seeking in youth: Web-based randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet. Res. 26 (e54478). https://doi.org/10.2196/54478 (2024).

Santelli, J. S. et al. Guidelines for adolescent health research: A position paper of the society for adolescent medicine. J. Adolesc. Health. 17, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(95)00181-Q (1995).

Schachter, D., Kleinman, I. & Harvey, W. Informed consent and adolescents. Can. J. Psychiatry. 50, 534–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370505000906 (2005).

Arnett, J. J. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55, 469–480 (2000).

Mehta, C. M., Arnett, J. J., Palmer, C. G. & Nelson, L. J. Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. Am. Psychol. 75, 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000600 (2020).

Wilhelm, M., Feldhege, J., Bauer, S. & Moessner, M. Einsatz internetbasierter verlaufsmessung in der psychotherapieforschung. Psychotherapeut 65, 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00278-020-00461-7 (2020).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 (2006).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Killen, J. D. et al. An attempt to modify unhealthful eating attitudes and weight regulation practices of young adolescent girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 13 (199305), 369–384. (1993).

Killen, J. D. et al. Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: A three-year prospective analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 16 (199411), 227–238. (1994).

Fischer, G. et al. The German version of the self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview (SITBI-G): A tool to assess non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior disorder. BMC Psychiatry 14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0265-0 (2014).

Bush, K. et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 (1998).

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R. & Grant, M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction 88, 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x (1993).

Kuitunen-Paul, S. & Roerecke, M. Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) and mortality risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 72, 856–863. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-210078 (2018).

Wilson, C. J., Deane, F. P., Ciarrochi, J. & Rickwood, D. Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the general Help-Seeking questionnaire. Can. J. Counselling. 39, 15–28 (2005).

Gaudiano, B. A., Davis, C. H., Miller, I. W. & Uebelacker, L. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a video self-help intervention for depression based on acceptance and commitment therapy: feasibility and acceptability. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 27, 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2436 (2020).

Wright, A., Jorm, A. F. & Mackinnon, A. J. Labels used by young people to describe mental disorders: which ones predict effective help-seeking choices? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 47, 917–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0399-z (2012).

Mond, J. M. et al. Eating disorders mental health literacy in low risk, high risk and symptomatic women: implications for health promotion programs. Eat. Disord. 18, 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2010.490115 (2010).

DeJong, H., Hillcoat, J., Perkins, S., Grover, M. & Schmidt, U. Illness perception in bulimia nervosa. J. Health Psychol. 17, 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311416874 (2012).

Lantz, B. The impact of sample non-normality on ANOVA and alternative methods. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 66, 224–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.2012.02047.x (2013).

Cohen, B. H. Explaining Psychological Statistics 3rd edn (Wiley, 2008).

Cohen, J. Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 (1992).

Tomczak, M. & Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends Sport Sci. 1, 19–25 (2014).

Lüpsen, H. R functions for the analysis of variance. https://www.uni-koeln.de/~luepsen/R/manual.pdf (2021).

Kilian, C. et al. Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: an updated systematic review of population studies. Alcoholism: Clin. Experimental Res. 45, 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14598 (2021).

Schomerus, G. et al. The stigma of alcohol dependence compared with other mental disorders: A review of population studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 46, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agq089 (2011).

Hammarlund, R., Crapanzano, K. A., Luce, L., Mulligan, L. & Ward, K. M. Review of the effects of self-stigma and perceived social stigma on the treatment-seeking decisions of individuals with drug- and alcohol-use disorders. Subst. Abuse Rehabilitation. 9, 115–136. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S183256 (2018).

Buscemi, J. et al. Help-seeking for alcohol-related problems in college students: correlates and preferred resources. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 24, 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021122 (2010).

Lubman, D. I. et al. Australian adolescents’ beliefs and help-seeking intentions towards peers experiencing symptoms of depression and alcohol misuse. BMC Public Health. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4655-3 (2017).

Yap, M. B., Wright, A. & Jorm, A. F. The influence of stigma on young people’s help-seeking intentions and beliefs about the helpfulness of various sources of help. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 46, 1257–1265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0300-5 (2011).

Lynch, L., Moorhead, A., Long, M. & Hawthorne-Steele, I. The role of informal sources of help in young people’s access to, engagement with, and maintenance in professional mental health Care—A scoping review. J. Child Fam. Stud. 32, 3350–3365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02498-5 (2023).

Villatoro, A. P., DuPont-Reyes, M. J., Phelan, J. C. & Link, B. G. Me versus them: how mental illness stigma influences adolescent help-seeking behaviors for oneself and recommendations for peers. Stigma Health. 7, 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000392 (2022).

Pfeiffer, S. & In-Albon, T. Gender specificity of self-stigma, public stigma, and help-seeking sources of mental disorders in youths. Stigma Health. 8, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000366 (2023).

Sheeran, P. & Webb, T. L. The Intention–Behavior gap. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 10, 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12265 (2016).

Doll, C. M. et al. Predictors of help-seeking behaviour in people with mental health problems: a 3-year prospective community study. BMC Psychiatry 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03435-4 (2021).

Pukas, L. et al. Prevalence and predictive factors for depressive symptoms among medical students in Germany - a cross-sectional study. GMS J. Med. Educ. 39 https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001534 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. Cost-effectiveness, and representativeness of facebook recruitment to suicide prevention research: online survey study. JMIR Mental Health 7 https://doi.org/10.2196/18762 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sabrina Baldofski, Elisabeth Kohls, Felicitas Mayr, and Maria I. Austermann for their support in the creation of the video materials for this study (DEP and ALC videos). We thank Lutfi Arikan (University Hospital Heidelberg) for enabling the technical implementation of this study.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (funding identifier: 01GL1904). The BMBF had no influence on the design of the study and was not involved in data collection, analysis and interpretation, or the writing of manuscripts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB, MM, and MK conceptualized the study. SB led the grant application. SB, MM, MK, and DL contributed to the study design and selection of screening and outcome measures. DL prepared the technical implementation of this study. DL, AM, EK, and SLK prepared the video interventions, under the supervision of MM, NA, HB, PP, CRK, RT, and SB, who also provided feedback and information within their fields of expertise. MM generated the random allocation sequence. DL was responsible for study recruitment, which was supported by student assistants. DL analysed the data, wrote the first draft of this manuscript and created its tables and figures, with SB and MM providing further feedback, guidance, and supervision during each step. All authors provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

PP is an advisor for Boehringer-Ingelheim and received speaker’s honoraria from Infectopharm, GSK, Janssen and Oral B. The other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee I of the Heidelberg Medical Faculty on 27th of July, 2020, protocol number S-378/2020. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants through an online checkbox agreement.

Parental informed consent

In accordance with the approval granted by the Ethics Committee I of the Heidelberg Medical Faculty, parental or guardian consent was formally waived for participation of minors in this anonymous online study. This decision was justified as follows: “Since this is an anonymous online survey and it cannot be verified whether the parents have actually given their consent by ticking the checkbox, this requirement can be waived in the present case.” (Ethics Committee I of the Heidelberg Medical Faculty, protocol number S-378/2020, statement from July-10-2020).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lemmer, D., Moessner, M., Arnaud, N. et al. An online vignette experiment on stigma and help-seeking attitudes towards five mental health problems in adolescents and emerging adults. Sci Rep 15, 29956 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11315-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11315-0