Abstract

Optimal scheduling of battery energy storage system plays crucial part in distributed energy system to provide stability and reduce user costs. Non-linear equipment characteristics (e.g., battery energy storage systems (BESS), electric power conversion have non-linear efficiency curves) can lead to errors in stored energy between the schedule and actual operation. This research proposes a technique to mitigate the occurrence of such errors in the BESS charging/discharging planning process by linearizing equipment nonlinear characteristics. This paper presents the implementation and comparison of three linearization techniques: special ordered set type 1 (SOS1), special ordered set type 2 (SOS2), and the Taylor method for the modeling and control of charging-discharging BESS, a DC/AC and AC/DC converters where non-linear efficiency curves are used. Also, the paper offers heuristics that allow effective selection of initial points for each of the intervals on the efficiency curves. There are presented experimental results confirming the effectiveness of the proposed control with different linearization approaches for solving operational problems caused by nonlinear characteristics of the equipment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern Energy Management Systems (EMS) must optimize the operation of distributed energy resources to ensure reliability, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness. A major challenge is capturing the nonlinear behavior of components like batteries and inverters, which directly impacts scheduling accuracy. Meanwhile, real-time and embedded applications impose strict computational constraints, demanding compact and efficient models. Although recent research1,2,3,4 seeks to improve accuracy without increasing complexity, it often relies on standard linearization techniques not adapted to the behavior of efficiency curves found in energy systems—limiting model fidelity. To address this gap, we propose the use of low-complexity linearization methods enhanced by a heuristic for selecting approximation points, enabling accurate representation of nonlinear efficiency curves without increasing the dimensionality of the optimization problem.

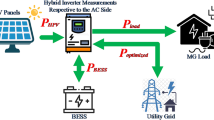

The energy system considered consists of a photovoltaic (PV) array, a battery energy storage system (BESS), residential loads, and inverters that connect the microgrid to the utility grid. Inverters convert DC from the PV and BESS into AC for local consumption, or convert grid-supplied AC to DC to charge the battery or meet EV charging demand. Residential loads can be supplied by PV generation, battery discharge, or grid electricity. The chosen topology represents a widely adopted and scalable solution for residential and commercial microgrids. Its relevance is confirmed by prior research on energy management4,5,6,7 and industrial competitions8. This architecture supports high renewable integration, bidirectional power flow, and flexible demand-side control, while its modular and cost-efficient design enables practical deployment in sustainable energy systems. At each time step t, the control system receives inputs such as electricity price, forecasted PV generation and load, and equipment parameters. Based on this, the algorithm computes the next battery state of charge \(SoC(t+1)\) and sends optimized commands to the controller. The microgrid architecture is illustrated in Fig. 1, with the system model and equipment specifications detailed in Sect. 1.

Recent works on energy management5,6,9 highlight the effectiveness of advanced strategies—such as teaching-learning-based optimization, adaptive model predictive control (MPC), and transactive control using metaheuristics—for reducing costs and improving flexibility. However, these approaches often operate at a high level of abstraction, relying on black-box models that do not explicitly behavior of equipments. This introduces a trade-off between short-term control performance and model transparency, where interpretable models offer greater long-term reliability, ease of validation, and suitability for deployment. Additionally, these studies rarely address computational efficiency—an essential consideration for real-time control in resource-constrained environments, such as smart microcontrollers. Solution times of metaheuristic methods can exceed those of piecewise-linearized models by several orders of magnitude10, and unlike these models, which can yield solutions close to the global optimum, metaheuristics offer no such guarantees, making them unsuitable for real-time control when effective linearization is possible. In contrast, Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) remains one of the most transparent and computationally efficient approaches for modeling and controlling energy management systems7,11. For instance,7 and11 utilize standard optimization software packages (solvers) to obtain scheduling solutions. To reduce complexity, many prior works simplify the model by neglecting network power flow constraints. However, while linear models enable tractable formulations, they fail to capture the nonlinear characteristics of component efficiency curves, thereby reducing the accuracy of the control action and the effectiveness of scheduling. Therefore, our research will consider a nonlinear model that takes into account the dependence of BESS and inverter efficiency on the power used. Previous studies, such as12,13, propose mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) approaches for demand response optimization, but they do not account for all equipment types with nonlinear efficiency characteristics and rely tools like AIMMS, which computationally expensive and does not allow solving large-scale problems. In14, a stochastic MINLP approach includes battery dynamics and AC power flow, but proposed algorithm decomposes the original MINLP problem into a subtask. However, this approach does not guarantee an optimal solution. Other works1,2,3,4 apply linearized MINLP models to enable MILP solvers, sacrificing accuracy. However, existing studies lack a comprehensive comparative analysis of multiple linearization techniques in terms of both solution quality and computational efficiency. In addition, none of the reviewed works propose a systematic methodology for selecting approximation points along component efficiency curves, which is critical for accurate and scalable linear modeling.

Piecewise linearization is commonly used in power system scheduling15. The special ordered set (SOS) method4 is a widely adopted technique to convert nonlinear functions into MILP-compatible forms. SOS1 allows at most one non-zero component and is computationally efficient, making it suitable for real-time applications. SOS2 permits two adjacent non-zero components, providing improved approximation accuracy while maintaining tractability. Taylor series16 enables local linearization of smooth nonlinear functions, capturing their curvature near operating points. These three methods were selected due to their solver compatibility, numerical stability, and favorable trade-offs between approximation quality and computational complexity. Alternative approaches—such as Big-M formulations17, McCormick envelopes18, and convex hull reformulations19—often require manual configuration, lead to weak relaxations or large model sizes, and are not always natively supported by solvers, which complicates practical implementation. Our study complements the selected techniques by introducing a novel heuristic algorithm for selecting optimal approximation points on efficiency curves, improving the quality of linearization for BESS and inverter models.

Our study introduces a novel heuristic algorithm for selecting optimal linearization points on nonlinear efficiency curves, enabling compact piecewise-linear approximations for BESS and inverter models. The key novelty lies in combining this point-selection heuristic with a lightweight SOS1-based linearization, which significantly reduces the number of auxiliary variables compared to more complex methods like SOS2 and SOS2+Taylor, achieving comparable or even superior solution quality. To evaluate the proposed approach, realistic energy consumption and production data were used. Electric vehicle demand was modeled based on20, considering factors such as day of the week, time, holidays, and charging station count. Residential load and PV output were based on Schneider Electric data21, while additional energy management data were taken from Driven Data8,22. Model-based strategies were compared against a baseline rule-based controller that charges the BESS at night and discharges it during the day when PV is insufficient. Performance was measured using the Score metric, which reflects the percentage reduction in electricity costs compared to the baseline. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in balancing accuracy and computational efficiency. The SOS1-based model with 30 intervals achieves a Score of 5.37% without heuristics, compared to 4.75% for the baseline MILP model. With the proposed heuristic for selecting linearization points, the Score increases to 5.46% without increasing the solution time (4.74 seconds). In contrast, SOS2 and SOS2 +Taylor models yield similar Scores (5.37%–5.41% without heuristics, 5.49%–5.50% with heuristics) but require 4–5\(\times\) longer runtimes (19.56–21.14 seconds). This highlights a favorable trade-off: our approach delivers near-optimal performance without the computational burden of more complex models, making it especially suitable for large-scale or real-time EMS applications, including deployment on embedded platforms.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 1 a description of the equipment and model of the power system considered in this paper is presented, and a review of the data for modeling. Section 2 describes existing optimization methods that can be used for EMS, including an approach base on MILP, an approach with linearization MINLP including SOS1, SOS2, Taylor series, and heuristic algorithms to find the best partition for each efficiency curve. Then an application of different models to schedule EMS will be discussed in Sect. 3. Section 4 contains the conclusion.

Energy management model formulation

This section describes the equipment parameters, the datasets used for experimentation, and the formulation of the energy management model as MINLP.

Energy equipment model description

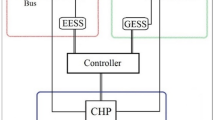

The energy system includes a PV plant,BESS, various loads, and inverters connecting the microgrid to the utility network, as shown in Fig. 1. Inverters convert DC from the battery and PV system to AC for the grid, with efficiency curves in Fig. 2b, and AC to DC for battery storage or EV charging, with efficiency in Fig. 2a. To reduce computational costs, average efficiency values are often used: 0.98 for AC/DC and 0.8 for DC/AC inverters.

BESS stores and discharges energy with efficiency over 96% in a wide operation area, when the battery voltage level drops the efficiency decreases significantly, as shown in Fig. 2c.Therefore, in the case of the linear model, the constant efficiency will be set at 0.96. The BESS has a maximum capacity of 2000 kWh, a minimum capacity of 600 kWh, and a maximum charging and discharging power of 800 kW.

Mathematical non-linear model of the energy system

Target function. The goal is to minimize total electricity costs from the grid over a one-day horizon (divided into 96 time intervals of 15 minutes). Electricity costs from the grid:

Energy balance equations. Electric balance equation for building electricity demand:

where \(D_{electricity}^{daily}(t)\) is the electiricity demand for lighting, elevator, socket in building, \(P_{Power-supply}^{AC}(t)\) is the power supply from AC flow, \(P_{Power-supply}^{DC}(t)\) is the power supply from DC flow, \(G^{dc/ac}(P_{Power-supply}^{DC}(t))\) – nonlinear function inverter DC/AC efficiency depending on power. The coefficients a, b, and c of the nonlinear function G is 62.91, -0.0000071, and 1.092 through curve fitting.

Energy balance equations. Electric balance equation (for demand and supply of electricity) for AC power line:

where \(P_{switch}(t)\) is the energy flow from the main grid to the DC flow, \(P_{switch}^{max}\) is the maximum possible energy flow from the main grid to the DC flow, \(y_{switch}(t)\) is the on/off state of the switch.

Energy balance equations. Electric balance equation (for demand and supply of electricity) for DC power line in non-linear formulation:

where \(P_{PV}(t)\) is the amount of electricity produced by PV panel at time t, \(P_{bess_{i}}^{ch}(t)\) is the BESS i charging power, \(P_{bess_{i}}^{dch}(t)\) is the BESS i discharging power, \(D_{electricity}^{PHEV}(t)\) is the electiricity demand for EV charging station, \(G^{ac/dc}(P_{switch}(t))\) – nonlinear function inverter AC/DC efficiency depending on power. The coefficients a, b, and c of the nonlinear function G is 7.72, -0.00001, and 1.002 through curve fitting.

BESS equations. Limitations on the charging and discharging rate, battery capacity:

where \(y_{bess_{i}}^{ch}(t)\) is the On/off state of the BESS i charge, \(y_{bess_{i}}^{dch}(t)\) is the On/off state of the BESS i discharge.

where \(P_{bess_{i}}^{dch, \max }\) is the maximum BESS i discharging power, \(P_{bess_{i}}^{ch, \max }\) is the maximum BESS i charging power.

where \(SoC_{i}(t)\) – state of charge BESS i, \(SoC_{max}^{i}\) is the maximum state of charge BESS i, \(SoC_{min}^{i}\) is the minimum state of charge BESS i.

Initializing the initial battery power and the battery power ratio between two consecutive steps:

where \(SoC_{In}^{i}\) – initial state of charge BESS i, \(G(P_{bess}^{ch/dch}(t))\) nonlinear function charging/discharging efficiency depending on BESS power. The coefficients a, b, and c of the nonlinear function G is 0.2326, 0.0477, and 0.9042 through curve fitting.

Capacity constraint:

where \(P_{grid }^{\max }\) is the maximum possible amount of electricity taken from main grid

Datasets description

A description of the energy dataset used in this research is as follows:

-

The residential load and PV output data were provided by Schneider Electric21 and Driven Data22. The dataset8 includes: historical building consumption and weather data, calendar information (workdays and holidays), meta-data about the building Data from over 200 buildings were collected. Forecast values were not used to avoid prediction error affecting model comparisons.

-

Electric vehicle load demand was modeled based on key factors such as day, time, and availability of charging stations20.

-

Electricity price trends reflect the time-of-use strategy in Beijing, with peak prices at ¥1.51/kWh and off-peak at ¥0.35/kWh. Typical peak hours are 8:30-11:30 AM and 6:00-11:00 PM.

The dataset provides time series data with 15-minute intervals for PV output, residential load, electric vehicle demand, and electricity prices for the next day (Fig. 3). The balance between energy demand and PV output cannot be achieved with PV energy alone, as peak generation occurs during the day, while energy demand persists throughout the day. A time-of-use pricing strategy encourages shifting electricity use to off-peak hours, optimizing energy use and reducing pollution. A battery storage system could store surplus PV energy or off-peak electricity for future use, especially during peak hours.

Optimization approaches

Microgrid energy management focuses on the optimal scheduling of distributed resources23,24. Traditional optimization approaches such as MILP and MINLP are commonly used, involving both continuous and discrete decision variables. While MILP formulations are well-supported by standard solvers and can efficiently provide globally optimal solutions, they are limited in modeling nonlinear relationships, such as equipment efficiency curves.

MINLP models, on the other hand, can capture such nonlinearities but are computationally intensive and often impractical for large-scale or real-time applications. To address this, many studies apply linearization techniques to reduce MINLP problems to MILP form, trading off model fidelity for tractability.

Heuristic algorithms offer an alternative by quickly approximating solutions to complex or large-scale problems without requiring exact optimality. Techniques such as genetic algorithms25 and evolutionary strategies26 are frequently used for energy system control. While heuristics may not guarantee globally optimal solutions, they are particularly effective for solving large problems and specific subtasks where exact methods become infeasible.

MILP

MILP is a mathematical optimization problem in which some or all variables must be integers. The target function and constraints are linear. The main advantage is the capability of solving rather large problems. Linear models do not describe the nonlinear characteristics of the battery and inverter’s efficiency curve. Therefore, this model uses the average value of the efficiency coefficient

Similar to the previous section the process used to mathematically model the energy management system, which consists of the following parts: electricity costs from the grid, energy balance equations, BESS - energy storage equations, capacity constraints. However, instead of an efficiency curve, the average value of the efficiency coefficient in the following formulas is used:

Energy balance equations. Electric balance equation for building electricity demand:

where \(\eta _{dc/ac}^{inv}\) – average inverter efficiency DC/AC

Electric balance equation (for demand and supply of electricity) for DC power line:

where \(\eta _{ac/dc}^{inv}\) is the average inverter efficiency AC/DC.

Initializing the initial battery power and the battery power ratio between two consecutive steps:

where \(\eta ^{ch}_{i}\) – average efficiency charge BESS i, \(\eta ^{dch}_{i}\) – average efficiency discharge BESS i

Linearization for MINLP

Transforming a non-linear model into a linear one often requires specific manipulations, substitutions, and the use of valid inequalities. Approximating complex functions linearly is a common technique in operations research and optimization. Linear approximations can simplify problem-solving by segmenting non-linear curves and applying linear interpolations. Figure 4 illustrates two examples of linearization: (a) shows a piecewise linear approximation of a non-linear function; (b) demonstrates a Taylor series linear approximation of an exponential function.

Piecewise approximations are widely used in engineering and mathematics15. They introduce linear segments to approximate non-linear functions, allowing the resulting linear problem to be solved more efficiently. Two main types of piecewise linearization are used: SOS1, where at most one variable in the set can be nonzero, and SOS2, where at most two variables can be nonzero and they must be adjacent. Another approach is Taylor’s theorem, which approximates f(x) around a point \(x = a\) using the first-order Taylor polynomial: \(f(x) \approx f(a) + f'(a)(x - a)\), where the error term \(h(x)(x - a)\) becomes negligible as x approaches a. Figure 4b demonstrates this linear approximation for \(f(x) = e^x\) around \(a = 0\).

The Taylor method can be applied together with the SOS2 method. The SOS2 method involves dividing the area of the function definition into intervals and using its mean value on that interval as the value of the function. However, if the Taylor function is used instead of the mean value at each interval, it will increase the accuracy of the approximation. The following is a mathematical formulation of the application of piecewise linear approximation of nonlinear functions including SOS1, SOS2, and Taylor series for the energy system controller.

MINLP + SOS1

To the model constraints described in subsection 1.2, the following constraints are added, to convert to a linear model.

BESS linearization constraints:

where \(\omega _{j,t,i}^{ch}\) and \(\omega _{j,t,i}^{dch}\) an array of boolean variables for each of the batteries, indicating which point on the curve to use (i.e. at what power to charge/discharge the battery) at each step.

Inverter linearization constraints:

where \(\omega _{j,t}^{ac/dc}\) and \(\omega _{j,t}^{dc/ac}\) an array of boolean variables, indicating which point on the curve to use (i.e. at what power convert DC to AC (and vice versa) using an inverter) at each step.

MINLP + SOS2

To the model constraints described in subsection 2.2.1, the following constraints are added, in order for the values of the control variables to be continuous.

BESS linearization constraints:

Inverter linearization constraints:

The value of the point at which the slope change occurs is the change point, and SOS2 proceeds with piecewise linearization as the sum of the weights of the change points at both ends of each interval. The variables \(u_{j,t,i}^{dch}\),\(u_{j,t,i}^{ch}\),\(u_{j,t}^{dc/ac}\),\(u_{j,t}^{ac/dc}\) are added for this purpose. The variables \(P_{bess_{i}}^{dch}(t)\), \(P_{bess_{i}}^{ch}(t)\), \(P_{Power-supply}^{DC}(t)\), and \(P_{switch}(t)\) can be calculated by using the near change points of the intervals \(u_{j,t,i}^{dch}\),\(u_{j,t,i}^{ch}\),\(u_{j,t}^{dc/ac}\),\(u_{j,t}^{ac/dc}\) and their weights (\(\omega _{j,t,i}^{dch}\), \(\omega _{j+1,t,i}^{dch}\)), (\(\omega _{j,t,i}^{ch}\), \(\omega _{j+1,t,i}^{ch}\)), (\(\omega _{j,t}^{dc/ac}\), \(\omega _{j+1,t}^{dc/ac}\)), (\(\omega _{j,t}^{ac/dc}\), \(\omega _{j+1,t}^{ac/dc}\)). Different from the SOS1 method, all weights are continuous values from 0 to 1.

MINLP + SOS2 + Tailor

The following constraints are added to the previous model:

Where \(\alpha _{j}\) and \(\beta _{j}\) – the coefficients of the line approximating the curve at each interval.

Computational complexity

The computational complexity of the linearization methods is evaluated in terms of the number of variables and constraints generated in the resulting mathematical programming models, which directly depends on the number of approximation intervals used. Figure 5 illustrates how these quantities scale with the number of intervals for the SOS1, SOS2, and SOS2 + Taylor methods (the latter coinciding in structure with SOS2).

The SOS2 and SOS2 + Taylor methods exhibit a steeper increase in model size: each additional interval introduces \(T \times 12\) new variables (1152 for the case study with a planning horizon \(T = 96\)), compared to \(T \times 6\) variables (572 for the same case) in the SOS1 method. While SOS2-based approaches achieve higher approximation accuracy with fewer intervals, the SOS1 method requires significantly more intervals to reach comparable accuracy, which may offset its initial computational advantage. However, with a more informed selection of approximation points—beyond uniform partitioning—the SOS1 method can maintain low computational complexity while achieving accuracy comparable to the more demanding SOS2 approach. A detailed evaluation of this trade-off and the optimal number of intervals for each method is provided in Sect. 3.

Heuristic-based linearization algorithms

A heuristic algorithm can efficiently support or replace traditional optimization by providing fast, targeted solutions. In this work, heuristics are used to select breakpoints for linearizing the efficiency curve, enabling more accurate approximations. Unlike standard sequential partitioning, which may overlook critical nonlinear regions, the proposed lightweight heuristic adaptively focuses on high-curvature areas where approximation errors are largest. The algorithm follows the steps outlined in Algorithm 1. It computes the discrete derivative of the efficiency curve and applies a dynamic thresholding scheme to identify points with the steepest slope changes. These points are then sorted and combined with boundary values to form the final set of linearization intervals. This strategy ensures denser point selection in regions with rapid efficiency variation, improving local approximation while keeping the total number of intervals manageable.

Proposed approach

Figure 6 presents a diagram of the proposed solution approach, which introduces a novel method for improving the accuracy and efficiency of energy management in microgrids. The proposed methodology combines domain-specific heuristics with efficient linearization techniques, making it suitable for real-time applications. The key steps are as follows:

-

Use of a domain-informed heuristic for selecting initial points on the nonlinear efficiency curves of BESS and inverters. Unlike standard uniform sampling, the heuristic prioritizes regions with higher curvature, leading to improved linearization accuracy with fewer segments.

-

Formulation of the MINLP that accounts for realistic nonlinear efficiency characteristics of key components. To address computational complexity, the model is linearized using the SOS1 method, which provides a favorable trade-off between accuracy and solver performance.

-

Solving the resulting MILP using commercial solvers, to obtain optimal control actions for the next time step (e.g., charge/discharge power, grid purchase decisions, SoC update).

This solution providing a low-complexity yet high-accuracy alternative to traditional nonlinear or uniformly linearized models.

Simulation results

This section explains the experimental design and tests the performance of the power system control algorithms based on four different mathematical models. The hardware that was used in the experiment is a PC with Intel Core i5-8600 with 6 cores and 3.10Ghz base frequency, 16 GB of RAM, and NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1060 with 6 GB of VRAM.

Baseline and score

All power system management strategies based on mathematical models are compared with the baseline rule-based control algorithm. Which consists of the following simple rules: charging BESS at night (lowest electricity price) and discharging BESS in a day (highest or higher electricity price) when PV generation cannot satisfy loading demand.

To present the optimization results, a baseline rule-based control algorithm is used as the benchmark, and the performance is measured using the metric \(\text {Score} = 100\% \times \left( 1 - \frac{Money_{\text {spent}}^{\text {model-based}}}{Money_{\text {spent}}^{\text {baseline-based}}} \right)\), which reflects the average relative cost savings of the model-based strategy compared to the baseline. Here, the numerator and denominator represent electricity costs under the model-based and baseline control strategies, respectively

Algorithms hypertuning

Before solving the obtained models it is necessary to determine the following hyperparameters: number of linearization intervals; initial points for each of the intervals on the efficiency curves; solver parameters (time limit, gap) .

Depending on how many points to take for linearization depends on the complexity of the model and as a consequence the computational cost. Choosing a large number of points will lead to high solution times, or even make the model nearly unsolvable. If too few points are chosen, the model will be too simple and will not give any improvement over the linear model. Table 1 shows a comparison of models when testing on 1 day, depending on the number of intervals for linearization.

Increasing the number of intervals significantly affects the speed of the solution in MNILP + SOS2, because increasing by one interval increases the number of constraints by 576 and the number of variables by 1152. However, in the discrete action model MNILP + SOS1, increasing the number of intervals does not affect the number of constraints, but to achieve the level of accuracy of the MNILP + SOS2 model it is necessary to increase the number of variables several times. Further increasing the number of intervals or discrete steps does not bring significant percent improvement compared to the solution time (Fig. 7).

To select the initial points for each of the intervals on the efficiency curves, we used the algorithm described in Sect. 2.3. Using this algorithm, it is able to create intervals for linearization in a very short time maintaining good accuracy. Figure 8 provides a comparison of approaches to the selection of initial points of intervals for sequential (with equal step) and heuristic method for 4 intervals for the BESS, AC/DC and DC/AC efficiency curve for SOS1(a) – (c), SOS2 (d) – (f), Taylor series (g) – (i) methods. The blue line represents the actual efficiency curve, the equation of which is 1.2. The green line represents an approximation of the efficiency curve with heuristic point selection, and the red line represents an approximation of the efficiency curve with sequential point selection.

The following metric (integrally calculated avarage accuracy) is used to compare approaches: \(P = 1 - \frac{\int _a^b (y - \hat{y})}{\int _a^b (y - 1)}\), where y - the value of the function on the approximation lines, \(\hat{y}\) - value of the real efficiency curve function, [a, b] - the interval in which the efficiency curve is determined. This metric shows how close the constructed approximation curve is to the real efficiency curve.

For intervals distributed uniformly on average for each curve (BESS, AC/DC, and DC/AC) the accuracy was 96.56% for SOS1, 97.67% for SOS2, and 99.03% for the Taylor series. In turn for heuristics, this metric was 97.93% for SOS1, 98.95% for SOS2, and 99.62% for the Taylor series.

To estimate the global solution, a genetic algorithm25 was used to select the initial points for each of the intervals on the efficiency curves. A genetic algorithm is a heuristic search algorithm used to solve optimization and modeling problems by randomly selecting, combining, and varying the desired parameters using mechanisms similar to natural selection in nature. This algorithm, in most cases, allows us to determine a solution close to the globally optimal one, but it requires significant computational resources27,28,29. The resulting solution provides an average accuracy for each curve (BESS, AC/DC and DC/AC) of 98.58% for SOS1, 99.61% for SOS2 and 99.91% for the Taylor series. Accordingly, the heuristic was possible to cover 99.3% to the global optimal solution obtained using the genetic algorithm, while for intervals distributed uniformly this value was 97.6%.

All mathematical formulations presented in Sect. 2 solved using Python 3.6 and MILP solver CBC30 is applied to solve MILP problem since it provides the best optimization results of open source solvers. The time limit of 15 minutes, relative MILP optimality gap of 0.03, and deterministic concurrent method are used for each MILP solution.

Algorithms comparison

To compare the effectiveness of the models under consideration, testing was conducted on 100 random test cases (days) with the equipment parameters described in the Sect. 1.1. The most important observation from the results in Table 2 is, that whilst the linear model is solved in 0.21 s, the nonlinear model linearized by the SOS1 method with 30 intervals can in turn be solved in an average of 4.74 s. The improvements in Score metrics were as follows 0.71 % (from 4.75 to 5.46). Two other linearization methods SOS2 and SOS2 + Tailor require more time to solve (19.56 and 21.14 s. respectively) and are therefore more difficult to compute, and the improvements in the Score metric compared to the linear model were, respectively 0.62%(from 4.75 to 5.37) and 0.66%(from 4.75 to 5.41). Application of the SOS1 method together with the proposed heuristic for selecting initial points for each of the intervals on the efficiency curves shows improvements in solving scheduling problems in EMS compared to traditional approaches.

To improve the MINLP + SOS2 and MNILP+ Taylor methods, a heuristic was applied to select initial points for each of the intervals on the efficiency curves (Table 3). This approach increased the percentage improvement by 0.12 and 0.09 for the MINLP + SOS2 and MNILP + Taylor methods, respectively. The results obtained are insignificantly more than in the SOS1 method, however, because of the high computational complexity, these approaches can be difficult to use when solving problems in the real world. A detailed comparison of the percentage of improvement on each day for all methods is given in Fig. 9. It is important to note that the choice of initial points for each of the intervals on the efficiency curves using heuristics can improve the accuracy of the model and obtain an increase in the percentage of optimization. Including some improvement can be obtained by applying heuristics to methods MINLP+SOS2 and MNILP+Taylor because of the specificity of these methods.

These findings demonstrate that the proposed method with SOS1-linearization with 30 intervals, when combined with the proposed heuristic for interval selection, offers a computationally lightweight yet highly accurate solution. Its low algorithmic complexity and minimal memory requirements make it particularly suitable for implementation on embedded platforms, such as smart microcontrollers. Notably, similar MILP-based energy management algorithms using the same open-source CBC solver have been successfully implemented on Raspberry Pi 2 Model B with a 900MHz quad-core ARM Cortex-A7 CPU, achieving acceptable solution times for real-time home energy management31. This confirms the practical feasibility of deploying such methods in embedded systems. While the referenced study demonstrates the feasibility of implementing simplified MILP-based load scheduling on embedded platforms, our approach extends this by incorporating nonlinear efficiency characteristics, offering improved planning accuracy while maintaining similarly low computational requirements—thus supporting practical deployment in real-world systems.

Conclusion

This study proposed an optimization approach that accounts for the nonlinear efficiency characteristics of BESS and inverters, using piecewise linearization techniques—SOS1, SOS2, and SOS2 combined with Taylor series expansion. To improve accuracy without increasing computational burden, we introduced a heuristic for selecting linearization breakpoints based on efficiency curve dynamics. To verify the performance of the proposed method, it was compared with an optimization model based on constant efficiency assumptions (i.e., a MILP approach). The linear model is simple and allows you to get a solution in a relatively short time, but it does not take into account the peculiarities of the equipment in which non-linear efficiency curves are used. Compared to a MILP model with constant efficiency assumptions, the proposed SOS1-based approach with 30 intervals and heuristic point selection improves scheduling performance by 0.71%. This gain is obtained by comparing two globally optimal solutions—one based on a simplified model with fixed efficiency, and the other incorporating nonlinear efficiency curves that more accurately reflect real equipment behavior. The improvement quantifies the contribution of modeling nonlinearity and selecting optimal linearization points, demonstrating that even small gains can deliver meaningful benefits in high-throughput energy systems without increasing computational complexity. Among the evaluated methods, SOS1 provided the best balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. More complex methods like SOS2 and SOS2 + Taylor achieved marginally better results but incurred significantly higher computational costs, limiting their practicality for real-time applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/NastiyaM/Linearization-Method-for-MINLP-Energy-Optimization-Problems-DATA.

References

Zhu, S., Liu, H., Xu, J., Chen, Z. & Niu, M. Study on the day-ahead co-operation strategy of regional integrated energy system including cchp. J. Eng. 2019, 5219–5223 (2019).

Geidl, M. & Andersson, G. Optimal power flow of multiple energy carriers. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 22, 145–155 (2007).

Bischi, A. et al. A detailed milp optimization model for combined cooling, heat and power system operation planning. Energy 74, 12–26 (2014).

de Farias Jr, I. R., Zhao, M. & Zhao, H. A special ordered set approach for optimizing a discontinuous separable piecewise linear function. Oper. Res. Lett. 36, 234–238 (2008).

Gbadega, P. A., Sun, Y. & Balogun, O. A. Advanced control technique for optimal power management of a prosumer-centric residential microgrid. IEEE Access (2024).

Gbadega, P. A. & Balogun, O. A. Transactive energy management for efficient scheduling and storage utilization in a grid-connected renewable energy-based microgrid. e-Prime-Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 100914 (2025).

Zhang, X., Son, Y. & Choi, S. Optimal scheduling of battery energy storage systems and demand response for distribution systems with high penetration of renewable energy sources. Energies 15, 2212 (2022).

Data exchange, (2022) optimizing storage demand-side strategies. https://shop.exchange.se.com/en-US/apps/39045/optimizing-storage-demand-side-strategies/overview (2022). Accessed: 2022-03-01.

Gbadega, P. A. & Saha, A. K. Impact of incorporating disturbance prediction on the performance of energy management systems in micro-grid. IEEE Access 8, 162855–162879 (2020).

Pickering, B., Ikeda, S., Choudhary, R. & Ooka, R. Comparison of metaheuristic and linear programming models for the purpose of optimising building energy supply operation schedule. In Proceedings of the CLIMA (2016).

Wang, J., Liu, J., Li, C., Zhou, Y. & Wu, J. Optimal scheduling of gas and electricity consumption in a smart home with a hybrid gas boiler and electric heating system. Energy 204, 117951 (2020).

Althaher, S., Mancarella, P. & Mutale, J. Automated demand response from home energy management system under dynamic pricing and power and comfort constraints. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 6, 1874–1883 (2015).

Bisschop, J. & Roelofs, M. Aimms-User’s Guide (Lulu. com, 2006).

Shuai, H., Fang, J., Ai, X., Wen, J. & He, H. Optimal real-time operation strategy for microgrid: An adp-based stochastic nonlinear optimization approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 10, 931–942 (2018).

Coffrin, C., Knueven, B., Holzer, J. & Vuffray, M. The impacts of convex piecewise linear cost formulations on ac optimal power flow. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 199, 107191 (2021).

Zhang, H., Vittal, V., Heydt, G. & Quintero, J. A relaxed ac optimal power flow model based on a taylor series. In 2013 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT Asia), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISGT-Asia.2013.6698739 (2013).

Kleinert, T. & Schmidt, M. Why there is no need to use a big-m in linear bilevel optimization: A computational study of two ready-to-use approaches. Comput. Manag. Sci. 20, 3 (2023).

Najman, J., Bongartz, D. & Mitsos, A. Linearization of mccormick relaxations and hybridization with the auxiliary variable method. J. Glob. Optim. 80, 731–756 (2021).

Sawaya, N. W. & Grossmann, I. E. Computational implementation of non-linear convex hull reformulation. Comput. Chem. Eng. 31, 856–866 (2007).

Chaudhari, K., Kandasamy, N. K., Krishnan, A., Ukil, A. & Gooi, H. B. Agent-based aggregated behavior modeling for electric vehicle charging load. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 15, 856–868. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2018.2823321 (2019).

Schneider electric, (2022) official website. https://www.se.com/ww/en/ (2022). Accessed: 2022-03-01.

Driven data, (2022) official website. https://www.drivendata.org (2022). Accessed: 2022-03-01.

Ahmad Khan, A., Naeem, M., Iqbal, M., Qaisar, S. & Anpalagan, A. A compendium of optimization objectives, constraints, tools and algorithms for energy management in microgrids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 58, 1664–1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.259 (2016).

Gamarra, C. & Guerrero, J. M. Computational optimization techniques applied to microgrids planning: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 48, 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.04.025 (2015).

Sidea, D.-O., Toma, L., Sanduleac, M., Picioroaga, I.-I. & Boicea, V.-A. Optimal bess scheduling strategy in microgrids based on genetic algorithms. In 2019 IEEE Milan PowerTech, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/PTC.2019.8810633 (2019).

Khunkitti, S., Boonluk, P. & Siritaratiwat, A. Optimal location and sizing of bess for performance improvement of distribution systems with high dg penetration. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 1–16, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6361243 (2022).

Markelova, A. et al. Applied routing problem for a fleet of delivery drones using a modified parallel genetic algorithm. Vestnik Saint Petersburg Univ. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. Control Process. 18, 135–148. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu10.2022.111 (2022).

Bezmaslov, M. et al. Optimizing dso requests management flexibility for home appliances using cbcc-rdg3. Computation https://doi.org/10.3390/computation10100188 (2022).

Sun, Q., Wu, H. & Petrosian, O. Optimal power allocation based on metaheuristic algorithms in wireless network. Mathematics https://doi.org/10.3390/math10183336 (2022).

Cbc package, (2022) cbc optimization. https://projects.coin-or.org/Cbc (2022). Accessed: 2022-03-01.

Soetedjo, A., Lomi, A. & Nakhoda, Y. I. Implementation of optimization technique on the embedded systems and wireless sensor networks for home energy management in smart grid. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Wireless Sensors (ICWiSE), 26–31 (IEEE, 2016).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by Postdoctoral International Exchange Program of China. The work of corresponding author is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72171126).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Z., A.M., A.A., O.P. and H.G.: conceptualization, original draft preparation, writing review and editing; A.Z. and O.P.: conceived the ideas and designed the methodology; A.M. and A.A.: collected and analysed the data; A.Z.: conceived and conducted the experiment, O.P. and H.G.: led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhadan, A., Martemyanov, A., Allahverdyan, A. et al. Linearization method for MINLP energy optimization problems. Sci Rep 15, 27853 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11380-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11380-5