Abstract

The use of copper slag instead of part of the slag to prepare alkali-activated cementitious materials can achieve the resource utilisation of copper slag, but alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials have the disadvantages of high shrinkage and low flexural strength, which limit their application in practical engineering. In order to improve its performance, this study used glass fiber, polypropylene fiber, steel fiber at 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, 1.0% by volume admixture into alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials, respectively, to explore the effect of fiber on the drying shrinkage and mechanical properties of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials. The test results show that the addition of fibers can compensate the drying shrinkage of AAMs and improve their mechanical properties. 1.0% of GF and SF can compensate the drying shrinkage of 17.5% and 27.3%, and PPF can also inhibit the drying shrinkage of the material, but the drying shrinkage will be exacerbated when the dosage is more than 0.8%. The addition of fibers does not have a significant effect on the compressive strength, but significantly improves the flexural strength of the material. When the dosage of GF, PPF and SF reaches 0.6%, 0.8% and 1.0% respectively, the flexural strength of the specimen at 28d is increased by 7.9%, 19.86% and 61.66% compared with that of the blank control group, respectively. Through microstructural analysis, it was found that the fibers formed a mesh structure in the material, which effectively inhibited the development of cracks and improved the toughness of the material. This study provides a theoretical basis and practical guidance for the optimization of the properties of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) has long been a cornerstone in construction, transportation, water conservancy, and various other sectors, driving the advancement of global infrastructure. Yet, its production comes at a steep environmental cost, contributing roughly 5–8% of worldwide CO2 emissions and consuming 10–15% of industrial energy annually1,2,3,4. In contrast, alkali-activated materials (AAMs) are gaining traction as a promising substitute for OPC, thanks to their lower energy demands, superior strength, and other notable benefits. This shift has captured the attention of researchers both at home and abroad, positioning AAMs as a key focus in the pursuit of sustainable construction solutions5,6. In the production process, AAM is produced without a calcination step, directly through the reaction of alkaline exciters, resulting in lower energy consumption and CO2 emissions compared to ordinary silicate cements7. In addition, AAM exhibits excellent mechanical properties and durability8,9,10, further strengthening its position as a potential alternative to OPC.

The surge in industrial growth over recent years has driven an unprecedented need for copper. However, the processes involved in mining and refining this metal produce substantial quantities of solid waste11,12, Among these by-products, copper slag (CS) stands out as a major residue, with the production of a single ton of copper yielding roughly 2.2 tons of CS13,14,15. At present, the main method of treating CS is landfilling, a method that takes up a lot of land resources while causing pollution of soil and groundwater resources16,17. The chemical composition of CS is similar to that of traditional precursors such as slag, both of which are dominated by SiO2, CaO, and Al2O318, and can exhibit better activity under alkali-activated, thus CS has the potential to be used as a precursor for the preparation of AAMs19. Preparation of AAMs is an effective means to deal with solid wastes, the use of CS instead of part of the slag preparation of AAMs to achieve the resource utilization of CS, can reduce the dependence on slag, reduce its adverse impact on the environment, save the large area of the CS landfill site to significantly reduce the carbon emissions and disposal costs20,21.

In recent years, more and more scholars have been devoted to the application of copper slag in the preparation of alkali-activated materials. Through microstructural analyses and property evaluations, researchers have confirmed the feasibility of copper slag as a precursor for alkali-activated materials and explored the effects of different factors (e.g., type of activator, dosage, condition of maintenance, particle size distribution, and chemical composition) on the macroscopic properties and microstructural evolution of the materials22,23,24. Xu et al.22 explored the possibility of employing CS as a substitute for varying amounts of GGBS in the creation of AAMs. Microstructural analysis revealed that, during alkali activation, the hydration of CS was rather limited. To improve its efficiency, additional research is essential to explore how various activator types and dosages, maintenance conditions, and the chemical makeup of coarse aggregates impact the macroscopic characteristics and microstructural development. Narasimhan et al.23 made use of CS as a replacement for river sand in alkali-activated slag concrete (AASC) formulations. Their findings indicated that AASC formulations utilizing either sand or CS exhibited comparable elastic modulus, reduced overall porosity, lower water absorption rates, and diminished chloride ion permeability when compared to traditional ordinary Portland cement concrete (OPCC) mixtures. Zheng et al.24 explored various quantities of CS in the formulation of alkali-activated permeable concrete. Their findings indicated that incorporating CS in the production of this type of concrete is a viable option, which is beneficial for the consumption of CS wastes and the reduction of carbon emission and cost of pervious concrete preparation.

Despite significant progress, alkali-activated materials prepared using CS still suffer from drawbacks such as high shrinkage and low flexural strength, which limit their application in practical engineering. To overcome these challenges, researchers have begun to explore ways to incorporate fibrous materials into alkali-activated materials. The addition of fibers not only improves the mechanical properties of the material, but also effectively limits its drying shrinkage25,26,27. Zhu et al.28 investigated the effect of different fibers on the ductility of alkali-activated slag cementitious materials (AASCM) and showed that plant fibers and polypropylene fibers retarded the crack propagation and enhanced the ductility of AASCM. Ahmad et al.29 added polypropylene fibers (PPF) to concrete prepared with alkali-inspired cementitious materials and the prepared concrete showed a reduction in both plastic cracking and crack development. Kan et al.30 investigated the long-term behaviour of alkali-inspired fiber-reinforced materials (AAFRC) cured at room temperature by incorporating polyethylene fibers (PE) in AAMs. The results showed that the compressive strength of AAFRC samples exhibited early strength characteristics, reaching nearly half of the peak value at 1 day, peaking at 28 days and remaining stable for a long period of time, and that AAFRC has good sustainability, good potential and excellent carbon emission performance compared to conventional concrete materials. Li et al.31 investigated the effect of steel fiber (SF) content on the mechanical properties of alkali excited slag-based concrete (AAC) with volume fractions of SF of 0.5%, 1% and 1.5%, which showed that SF did not have a significant effect on the compressive strength of AAC, but significantly increased the splitting tensile strength and flexural properties of the concrete. Choi et al.32 incorporated hybrid fibers of PVA and PE fibers into alkali-activated slag-based composites (AAS) to investigate the effect of hybrid fiber reinforcement on the mechanical properties and self-healing ability of AAS, and the results showed that the hybrid fibers improved the tensile strain capacity and self-healing ability of the composites. By incorporating fibers into AAMs, the chaotic distribution of fibers in AAMs can act as a connection and reduce the development of cracks, thus improving the continuity of the material25. When an external load is applied, both the fibers and the matrix share the burden. The fibers act like tiny bridges, ensuring that any cracks in the matrix remain discontinuous, ultimately boosting the matrix’s overall toughness33,34.

This study delves into the impact of incorporating fibers on the engineering properties of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials. We introduced different types of fibers at different volume fractions to see how they affect the drying shrinkage and strength of the composites. To understand the fundamental mechanisms through which fibers enhance the material, we took a close look at the pore structure and microstructure of the samples, employing XRD and SEM techniques. This was done in order to better understand the effect of fiber incorporation on the internal pores of the material and how the fibers and the alkali activated matrix work in tandem, and ultimately to clarify their role in improving the overall performance of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials.

Materials and methods

Raw material

The CS used in this study was sourced from a smelter in Hebei Province and consisted of slag rapidly cooled in high-temperature water. This slag was initially crushed, then further refined via ball milling. We then sieved the resulting CS powder using a 0.075 mm standard sieve to ensure it met the particle size specifications for our experiments. The CS powder had a density of 3.32 g/cm3 and a specific surface area of 1344 cm2/kg. The ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS) was obtained from a mineral processing plant located in Lingshou Country. This GGBS exhibited a density of 2.86 g/cm3 and a specific surface area of 1030 cm2/kg.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the CS and GGBS samples are displayed, while their chemical makeup is detailed in Table 1. The particle size distribution for CS and GGBS is depicted in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. Additionally, the XRD patterns can be observed in Fig. 4.

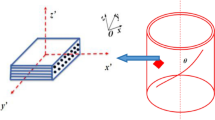

The three fibers used in this study are glass fiber (GF), polypropylene fiber (PPF) and steel fiber (SF). The sample diagrams of the three fibers are shown in Fig. 5 and the parametric indices are shown in Table 2.

Methods

Mix proportion

The mortar water-cement ratio was 0.55, the mass ratio of CS to GGBS was 3:7, the alkaline exciter water–glass modulus and alkali equivalent were 1.5 and 8, respectively, and the fibers were doped according to volumetric admixture, and each type of fiber was divided into five groups, and the admixture of fibers was set to be 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, and 1.0%, respectively. The test blocks produced were recorded as the control group D0 without fiber doping. the test blocks doped with GF were recorded as G-2, G-4, G-6, G-8, G-10; the test blocks doped with PPF were recorded as P-2, P-4, P-6, P-8, P-10; and the test blocks doped with SF were recorded as S-2, S-4, S-6, S-8, S-10. The preparation process of mortar was as follows: firstly, CS and GGBS were mixed well, and then standard sand was added to the mortar. Mixed evenly, then add the standard sand and fiber to continue mixing, and finally add water glass and water, mix evenly and then pour into the mold to maintain the shape. The mixing ratio of each group of specimens is shown in Table 3.

Test methods

Testing of the mineral composition of raw materials by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The tests were conducted with a D8 Advance series device manufactured by Bruker in Germany. The test parameters are: copper target, 40 kV, 36 mA, step size 0.02°/step, speed 0.6°/min, scanning range (2θ) of 10°–60°. The samples were finely ground through a 75 μm standard sieve and dried in a drying oven at 105 °C before testing.

The fluidity of alkali-activated copper slag–slag cementitious materials was assessed using the guidelines outlined in GB/T2419-2005, which details the “Method for Determination of Fluidity of Cementitious Sand.”

Drying shrinkage test: After the specimen is demoulded, the specimen is cured at 20 ± 2 °C, relative humidity ≥ 95% for 3 days to ensure that the specimen reaches a stable initial state, and the length of the specimen at the age of 3d is taken as the initial length of the specimen (zero point of drying shrinkage). Thereafter, the lengths of 7d, 14d, 21d, 28d, 42d, 56d and 90d were measured at specified intervals. Concrete shrinkage deformation was measured using a digital micrometer with an accuracy of 0.001 mm. The zero point of the meter was calibrated with a standard rod before each shrinkage measurement and was double-checked at least 1–2 times more during the determination process.

Flexural and compressive strength were gauged by adhering to the protocols described in GB/T17671-2021, the “Method for Testing Strength of Cementitious Sand (ISO)”. Mortar specimens, measuring 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm, were used. For each test, three parallel specimens from a triple mold were prepared, and the average of their results was taken to represent the overall strength data.

To analyze the pore architecture of alkali-activated cementitious materials, low-field nuclear magnetic resonance was employed as the primary method. Prior to conducting the pore structure assessment, the samples underwent a vacuum saturation process that lasted a minimum of 24 h. After saturation, the excess water on the surface of the specimen was dried with a towel, sealed with PTFE tape to prevent evaporation of water, and placed on the instrument for testing. The equipment used was the MesoMR23-060 V-1 series produced by Suzhou Newsmax, with a magnetic field strength of 0.5 ± 0.08 T and a main frequency of 21.3 MHz.

The hydration reaction product microstructure was examined through SEM. The model of the testing instrument chosen was a Pharos-SED-EDSG220023-F series bench-top SEM manufactured by Feiner Phenom, the Netherlands. The samples were finely ground and sieved before testing, and dried with water in a drying oven, and sprayed with gold using a high-resolution sputter coater.

Results and discussion

Fluidity

The flow characteristics of the alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious material are illustrated in Fig. 6. In the absence of fiber, the matrix of the alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious material demonstrates superior mobility, measuring at 228.45 mm. However, with the inclusion of GF, PPF, and SF fibers, there is a noticeable decrease in mobility after the alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious material, and the greater the dosage of fibers, the lower the mobility. When the amount of doping is 1.0%, doped GF, PPF, SF matrix fluidity values of 195.05 mm, 201.50 mm and 206.40 mm, respectively, compared with the non-doped fiber matrix decreased by 14.62%, 11.80%, 9.65%, respectively, which can be seen that the GF on the decline in the fluidity of the largest impact, followed by the second PPF, the smallest impact of SF.

Fiber doping into alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials can have a strong bonding effect with the matrix35, and play a supporting role in the matrix, increasing the system friction, so that the alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials flow is reduced36 When the SF content is higher, fiber clusters will be formed, and the decrease in matrix flowability will increase37,38, which can also be seen in Fig. 6. When the SF doping is greater than 0.6%, the decrease in matrix flowability increases. While GF and PPF have better cohesive polymerization in contact with water39, the fibers and mortar matrix are tightly bonded, the more fiber doping, the more mortar wrapped, and the lower the mortar fluidity40. For the three types of fibers of 12 mm, the number of GF is about 3.77 × 109 fibers/m3, PPF is about 4.72 × 108 fibers/m3, and SF is about 2.65 × 106 fibers/m3, when the fiber doping is the same, the number of roots of GF is more, which will form a denser mesh structure in the system and greatly reduce the flow of composite cementitious materials41. The surface area per unit volume is about 2135 m2/m3 for GF, about 534 m2/m3 for PPF, and about 20 m2/m3 for SF. The larger the surface area per unit volume, the higher the fiber-matrix frictional resistance, and the more significant the decrease in flowability. GF has the greatest effect on the flowability decrease, PPF is second and SF has the least effect.

Drying shrinkage

The drying shrinkage of all specimens gradually stabilised with the increase of the age of curing. The lengths of all mortar specimens were basically stable up to the 90th d of age. In the early period (0–14 days), the rapid increase in drying shrinkage was mainly driven by the kinetics of the geopolymer condensation reaction. Alkaline exciters triggered rapid depolymerisation and reorganisation of the precursors to form a three-dimensional gel network. This process is accompanied by the depletion of bound water and a sharp release of pore fluid capillary tension, which ultimately leads to significant shrinkage of the specimen in the early stages42. At the later stage (> 28 d), the stabilisation of drying shrinkage can be attributed to a two-stage mechanism: firstly, the reconstruction rate of the geopolymer gel network slows down significantly as the concentration of the reactants decreases, and the driving force for chemical shrinkage is weakened; and secondly, the pore structure of the matrix is gradually densified, and the proportion of the connected pores decreases, which obstructs the moisture diffusion pathway, and the selfdrying effect becomes saturated, ultimately resulting in the specimen drying shrinkage in the later stage reduction43. All three fibers had a compensating effect on the drying shrinkage of the specimens. The variation of drying shrinkage strain of specimens with age is shown in Fig. 7. Specifically, the drying shrinkage strain of the control D-0 specimen was 988 με up to the age of 90 d. The drying shrinkage of the specimen decreased with the increase of the dosage of GF and SF, and the drying shrinkage of the specimen with the dosage of GF of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 was 950 με, 916 με, 887 με, 853 με, and 815 με, which was 3.8%, 7.3%, 10.2%, 13.6%, and 17.5% lower than that of the unadulterated specimen, respectively. The drying shrinkage was reduced by 3.8%, 7.3%, 10.2%, 13.6% and 17.5%, respectively. The drying shrinkage values of specimens with SF dosage of 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 were 940 με, 876 με, 795 με, 750 με and 718 με, which were 4.8%, 11.3%, 19.5%, 24.1% and 27.3% lower than those of the specimens without fiber doping, respectively. However, for PPF, the drying shrinkage of the specimens is negatively affected when the dosage exceeds 0.6%, and the drying shrinkage strains of the specimens with PPF dosed at 8% and 10% were 1038 με and 1060 με up to the age of 90 d, which were increased by 5.1% and 7.3%, respectively, compared with those of the blank control specimens. PPF itself is hydrophobic, the interface between the fiber and the matrix forms capillary pores, When the PPF doping is too high the excess fiber increases these pore networks to accelerate water evaporation, resulting in increased drying shrinkage.

Specimen damage pattern

The damage morphology of the specimen after being subjected to pressure is shown in Fig. 8. The four specimens in the figure are from the blank control group D-0 and 1% fiber doping groups G-10, P-10 and S-10. The specimen without fiber doping reaches the load-bearing limit state without obvious signs, and directly cracks, which is a typical brittle damage. Undoped fiber specimen has many internal pores and defects, these pores and defects are very easy to produce stress concentration phenomenon. When subjected to external forces, the specimen will be the first to carry out cracks in the stress concentration, because there are no fiber constraints, crack development is rapid, and the specimen will soon be blown up with the cracks, the damage occurs. After GF is added, the specimen will still crack after being subjected to the pressure of the limit state, but it will not blow up and the specimen will have fewer internal cracks. The specimen doped with PPF and SF, before being damaged by the pressure, a continuous “squeak” can be heard, the specimen is damaged and there is no debris collapse, the specimen produces a lot of small cracks, cracks in the fiber bridging the matrix, cracking, but not broken phenomenon.

The uniaxial compressive stress–strain curves of the four groups of specimens during the compressive strength tests are shown in Fig. 9. Macroscopic fracture photographs provide a qualitative description of the damage pattern. Complete uniaxial compressive stress–strain curves, and the toughening effect of the three fibers can be quantitatively characterised by calculating the toughness index and residual strength factor. The toughness index and residual strength factor of concrete specimens after compression damage are important indicators for evaluating their ductile properties and bearing capacity after damage. The toughness index reflects the ability of concrete to absorb energy in the damage process, usually calculated by the area under the stress–strain curve, such as the ratio of energy before and after the peak stress, and the residual strength factor is the ratio of the remaining strength to the peak strength after damage, such as the ratio of the stress to the peak stress at a certain point in the descending section of the stress–strain curve. The higher toughness index indicates that the concrete can withstand greater plastic deformation before destruction, the better the ductility. The higher residual strength factor indicates that the specimen can still maintain a high bearing capacity even after cracking. After calculating the load–displacement curve, the toughness index of the empty 100 control specimens is 0.51, and the residual strength factor is 0.06. The toughness index of the three groups of specimens, G-10, P-10, and S-10, is 1.34, 1.72, and 2.96, respectively, and the residual strength factor is 0.11, 0.14, and 0.21, respectively, and the toughness-enhancing effect of SF is better than that of GF and PPF.

The damage pattern of the specimen after the flexural strength test is shown in Fig. 10, from which it can be seen that the specimen without fiber doping and the specimen with GF doping will be broken into two. Undoped fiber specimens in the destruction of no sign, directly “bang” sound broken into two, showing a typical brittle damage pattern. The GF-doped specimen has a short fracture process, and finally breaks into two; PPF-doped specimen will produce a large crack, the middle of the crack has been pulled out of the PPF; SF-doped specimen in the flexural strength test only produces a very small crack, can be seen at the edge of the crack with SF distribution.

Analysis of compressive and flexural strength

Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the compressive and flexural strength of the samples, varying GF volume. When it comes to flexural strength, we see an initial increase followed by a decrease as the GF dosage goes up. The sweet spot, where flexural strength peaked, was at a GF dosage of 0.6%. On the other hand, adding GF didn’t seem to make a huge difference in compressive strength. When GF is incorporated into the matrix, the fibers tend to scatter randomly within the specimen, creating a network structure that collaborates with the matrix to withstand applied forces41. When external forces induce cracks in the matrix, the fibers can effectively bridge these gaps, mitigating further crack propagation33.

Figures 13 and 14 illustrate the compressive and flexural strength of samples incorporating varying levels of PPF. According to previous studies, the incorporation of polypropylene fibers has little effect on the enhancement of compressive strength44. This was also verified by the test data, where a reduction in the compressive strength of the specimens was also observed at PPF dosages above 0.8%. The flexural strength of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious material increases and then decreases with the increase of PPF dosage, and reaches a larger value when the dosage of PPF is 0.8%, and the flexural strengths of 3d, 7d, and 28d are 8.46 Mpa, 10.99 Mpa, and 12.79 Mpa, respectively, and compared with that of the control group D0 with no fibers, they are respectively increased by 14.32%, 18.15%, and 19.86%.

Figures 15 and 16 illustrate the compressive and flexural strength of samples incorporating varying SF dosages. When comparing the compressive strength of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious material samples cured for 3 and 7 days to samples without fiber reinforcement, a decrease was observed with the introduction of 2% SF. However, with SF additions starting at 4%, both the compressive and flexural strengths of the 3-day and 7-day cured specimens began to pick up, showing an increasing trend as the SF dosage went up, and the flexural strengths increased by a larger amount. When the SF doping was 1.0%, the corresponding flexural strengths of 3d, 7d, and 28d were 12.59 Mpa, 15.08 Mpa, and 17.25 Mpa, respectively, which were enhanced by 70.13%, 62.15%, and 61.66% compared to the matrix without fiber doping. The effect of SF doping on the compressive strength of the matrix is not significant, when the SF doping is 1.0%, the compressive strength of 3d, 7d, 28d corresponds to 1.02%, 7.31%, 3.81% compared with that of the matrix without fiber doping, respectively. And the rate of strength increase becomes slower when the SF doping exceeds 0.6%. This is because when the volume content of SF exceeds a certain value, the phenomenon of “agglomeration” will occur45, increasing the number of defects within the matrix, too many defects will weaken the strength of the matrix, which will lead to alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious material performance reduction.

The addition of fibers does not have a significant effect on the compressive strength of the material, but has a more pronounced effect on the flexural strength, especially for GF. The load displacement curve of the specimen under bending stress is shown in Fig. 17. The peak load of the load–displacement curve corresponds to the flexural strength of the specimen, and the slope and shape of the curve can reflect the deformation capacity and ductility of the specimen. It can be seen from the load and displacement curves under bending stress that the peak load of the specimens in the blank control group and the GF group decreases abruptly after reaching the peak load, and the residual section is not obvious, and the peak load of the specimens in the PPF group and the SF group decreases more gently than that of the blank control group and the GF group, and the residual section is obvious. The peak load of the specimens in the SF group is higher than that of the GF and the PPF group, and the toughness and the flexural strength of the materials in the SF group are better than those of the GF and the PPF group GF and PPF.

Compressive to flexural ratio analysis

The compressive to flexural ratio histograms of specimens doped with three different fibers are shown in Figs. 18, 19 and 20. The histograms of the compressive to flexural ratio indicate a decrease followed by an increase as GF doping rises, and the compressive to flexural ratio is the lowest when the GF doping is 0.6%, and the compressive to flexural ratio of 3d, 7d and 28d are 7.25, 6.93, 7.02, which are reduced by 8.55%, respectively, compared with that of the control group D0 without doping fibers, 7.09%, 6.64%, indicating that GF improved the toughness of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials. With the increase of PPF doping, alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious material compressive to flexural ratio decreases, when the PPF doping of 1.0% 3d, 7d, 28d compressive to flexural ratio of 5.91, 5.88 and 6.08, respectively, compared with the control group D0 without fiber doping were reduced by 25.39%, 21.19% and 19.10%, indicating that the PPF has a composite collodion material with crack-resistant and toughening effect. With the increase of SF doping, the compressive to flexural ratio decreases, and the compressive to flexural ratio of 28d is only 4.83 when the SF doping is 1.0%, which is 35.78% lower than that of D0 in the control group without fiber doping, indicating that SF has an improved effect on the flexibility of composite cementitious materials.

Pore structure

The mechanical properties of Alkali-activated copper slag–slag cementitious materials are heavily dependent on their pore structure. As shown in Fig. 21, the effects of adding 1.0% fibers on both pore size distribution and partial porosity were assessed following a 28-day curing period. It’s worth noting that the key factor influencing the mechanical behavior of these materials isn’t just the overall porosity but rather the specific distribution of pore sizes. This distinction plays a pivotal role in shaping their performance46. Previous studies have classified pores into several categories based on size: those under 20 nm are generally considered benign, pores between 20 and 50 nm pose a slight risk, those ranging from 50 to 200 nm are harmful, and pores exceeding 200 nm are the most problematic47. Looking at Fig. 21 it’s clear that adding fibers to the alkali-activated copper slag–slag cementitious materials leads to a greater number of both the smallest, harmless pores and the largest, most harmful ones. The significant jump in the volume of these more damaging pores is likely due to the fact that the fibers are finer than both the CS and GGBS particles. Essentially, cramming in more fibers throws off the particle size distribution within the mix, which in turn expands the volume of these larger, more harmful pores. This shift in the pore structure ultimately takes a toll on the material’s mechanical strength. The most significant increase in the volume of more harmful pores was observed in specimen P-10, which has 1.0% fiber doping, followed closely by specimen G-10, also with 1.0% fiber doping. This trend correlates with the findings from the compressive strength tests, where both specimens P-10 and G-10 exhibited reduced 28-day compressive strengths compared to specimen D-0. In conclusion, while the addition of fibers to alkali-activated copper slag–slag cementitious materials can result in a greater volume of harmless pores, it simultaneously contributes to an increase in the volume of more harmful pores. Consequently, excessive fiber doping can lead to a decline in the mechanical properties of the material.

Microscopic morphology

Figure 22 shows the SEM patterns of the specimens doped with GF, PPF, and SF at 1.0% dosing as well as the cross-sections of the specimens without fiber doping. From the figure, it can be seen that the fiber is more uniformly distributed in the cementitious material, and the bond between the fiber and the cementitious material is better. Moreover, the fibers have better working performance in highly alkaline environment48, and no serious dissolution phenomenon occurred. Within the matrix, the fibers create a network, acting like a supportive skeleton. When external forces cause the matrix to crack, the fibers step in, effectively stopping the crack from spreading and easing the stress buildup through a bridging action. What’s more, these fibers also help keep cracks from wandering off course or splitting, ultimately boosting the matrix’s toughness27. Examination of the fracture surfaces reveals a significant presence of hydration products on the fiber surfaces, suggesting that the friction generated as the fibers are pulled out from the matrix contributes to bearing the external load. This interaction ultimately boosts the matrix’s strength.

When the external load is larger, GF is pulled off because it cannot resist the external force. PPF and SF are more likely to have a strong bond with the matrix compared to GF, which will play a role in connecting the two ends at the matrix defects and better improve the strength and toughness of the matrix49.

Conclusions

In this study, CS was used to make alkali-activated cementitious materials instead of some GGBS and three different types of fibers were added to the materials to systematically evaluate the effect of fibers on the properties of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials Experimental studies have led to the following conclusions:

-

1.

The inclusion of fibers in alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials can adversely affect the flowability of the materials. For the same amount of the three fibers, the amount of GF is much larger than that of PPF and SF and the surface area per unit volume of GF is larger, which reduces the fluidity of the material.

-

2.

Both GF and SF can effectively inhibit the drying shrinkage of alkali-inspired cementitious materials, and the inhibition effect is enhanced with the increase of fiber dosage. 1.0% of GF and SF reduced the drying shrinkage by 17.5% and 27.3%, respectively, with steel fibers having a more significant compensatory effect at 90 d. PPF did not have a significant negative impact on the shrinkage at a low dosage, but a high dosage aggravated the drying shrinkage.

-

3.

Fibers have little effect on the compressive strength of alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials but have a significant effect on the flexural strength. Among them, the flexural strength of 1% volume doped GF specimen at 28d is as high as 17.25 Mpa, which is 61.66% higher than that of the blank group specimen, and the toughening effect of GF is better than that of GF and PPF.

-

4.

The excessive addition of fibers destroys the uniformity of the particle size distribution in the precursor, leading to an increase in the proportion of harmful pores in the material. This microstructural alteration adversely affects the mechanical and durability properties of the material.

-

5.

Fiber-reinforced alkali-activated copper slag–slag composite cementitious materials, despite certain advantages, still face the challenges of scalability, long-term durability and barriers to industrial application. Fluctuations in the composition of CS and GGBS may affect the stability of reactivity and mechanical properties, limiting the large-scale production of the long term performance still needs to be verified in-depth; in addition, the corrosive nature of high alkali exciters also restricts the industrial application. Future research can focus on the pretreatment technology of copper slag and the development of low alkali exciters to promote their large-scale application in the field of building materials.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Amran, Y. M., Alyousef, R., Alabduljabbar, H. & El-Zeadani, M. Clean production and properties of geopolymer concrete; A review. J. Clean. Prod. 251, 119679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119679 (2020).

Karayannis, V. G., Moustakas, K. G., Baklavaridis, A. N. & Domopoulou, A. E. Sustainable ash-based geopolymers. Chem. Eng. Trans. 63, 505–510. https://doi.org/10.3303/CET1863085 (2018).

Amran, M., Debbarma, S. & Ozbakkaloglu, T. Fly ash-based eco-friendly geopolymer concrete: A critical review of the long-term durability properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 270, 121857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121857 (2021).

Siddika, A. et al. Performance of sustainable green concrete incorporated with fly ash, rice husk ash, and stone dust. Acta Polytech. https://doi.org/10.14311/AP.2021.61.0279 (2021).

Sun, B., Ye, G. & De Schutter, G. A review: Reaction mechanism and strength of slag and fly ash-based alkali-activated materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 326, 126843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126843 (2022).

Tayeh, B. A., Hamada, H. M., Almeshal, I. & Bakar, B. A. Durability and mechanical properties of cement concrete comprising pozzolanic materials with alkali-activated binder: A comprehensive review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01429 (2022).

Elzeadani, M., Bompa, D. & Elghazouli, A. One part alkali activated materials: A state-of-the-art review. J. Build. Eng. 57, 104871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104871 (2022).

Wardhono, A., Gunasekara, C., Law, D. W. & Setunge, S. Comparison of long term performance between alkali activated slag and fly ash geopolymer concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 143, 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.153 (2017).

Ramagiri, K. K. & Kar, A. Environmental impact assessment of alkali-activated mortar with waste precursors and activators. J. Build. Eng. 44, 103391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103391 (2021).

Ding, Y., Dai, J.-G. & Shi, C.-J. Mechanical properties of alkali-activated concrete: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 127, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.121 (2016).

Kundu, T., Senapati, S., Das, S. K., Angadi, S. I. & Rath, S. S. A comprehensive review on the recovery of copper values from copper slag. Powder Technol. 426, 118693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2023.118693 (2023).

Tian, H. et al. Comprehensive review on metallurgical recycling and cleaning of copper slag. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 168, 105366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105366 (2021).

Singh, J. & Singh, S. Development of alkali-activated cementitious material using copper slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 211, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.233 (2019).

Yan, Z. et al. Mechanical performance and reaction mechanism of copper slag activated with sodium silicate or sodium hydroxide. Constr. Build. Mater. 266, 120900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120900 (2021).

Shi, C., Meyer, C. & Behnood, A. Utilization of copper slag in cement and concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 52(10), 1115–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2008.06.008 (2008).

Casagrande, C. A., Roque, J. S., Jochem, L. F., Correa, J. N. & Medeiros, A. Copper slag in cementitious composites: A systematic review. J. Build. Eng. 78, 107725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107725 (2023).

Wang, Z., Gao, J., Lan, X. & Guo, Z. A green method to clean copper slag and rapidly recover copper resources via reduction-sulfurizing smelting and super-gravity separation at low temperature. J. Hazard. Mater. 468, 133834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.133834 (2024).

Wang, R., Shi, Q., Li, Y., Cao, Z. & Si, Z. A critical review on the use of copper slag (CS) as a substitute constituent in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 292, 123371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123371 (2021).

Nazer, Payá, J., Borrachero, M. V. & Monzó, J. Use of ancient copper slags in Portland cement and alkali activated cement matrices. J. Environ. Manag. 167, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.11.024 (2016).

Zain, M., Islam, M., Radin, S. & Yap, S. Cement-based solidification for the safe disposal of blasted copper slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 26(7), 845–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2003.08.002 (2004).

Gursel, A. P. & Ostertag, C. Life-cycle assessment of high-strength concrete mixtures with copper slag as sand replacement. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019(1), 6815348. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6815348 (2019).

Xu, R., Wang, H., Yang, R., Kong, F. & Hong, T. The potential of copper slag as a precursor for partially substituting blast furnace slag to prepare alkali-activated materials. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 140283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140283 (2024).

Mithun, B. & Narasimhan, M. Performance of alkali activated slag concrete mixes incorporating copper slag as fine aggregate. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 837–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.026 (2016).

Zheng, X. et al. Utilization of copper slag waste in alkali-activated metakaolin pervious concrete. J. Build. Eng. 76, 107246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107246 (2023).

Adesina, S. Das, Drying shrinkage and permeability properties of fibre reinforced alkali-activated composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 251, 119076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119076 (2020).

Puertas, F., Gil-Maroto, A., Palacios, M. & Amat, T. Alkali-activated slag mortars reinforced with AR glassfibre performance and properties. Mater. Constr. 56(283), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.3989/mc.2006.v56.i283.10 (2006).

Chen, W. et al. Role of aggregate and fibre in strength and drying shrinkage of alkali-activated slag mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 299, 124002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124002 (2021).

Zhu, J., Zheng, W. Z., Qin, C. Z., Xu, Z. Z., Wu, Y. Q. Effect of different fibers on mechanical properties and ductility of alkali-activated slag cementitious material. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering Vol. 292, no. 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/292/1/012060.

Tošić, N. et al. Multi-recycling of polypropylene fibre reinforced concrete: Influence of recycled aggregate properties on new concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 346, 128458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128458 (2022).

Kan, L. et al. Long-term behaviors of fiber reinforced alkali-activated composite cured at ambient condition: Mechanical characterization. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e03306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03306 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Effect of recycled aggregate and steel fiber contents on the mechanical properties and sustainability aspects of alkali-activated slag-based concrete. J. Build. Eng. 66, 105939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.105939 (2023).

Choi, J., Nguyễn, H. H., Park, S. E., Ranade, R. & Lee, B. Y. Effects of fiber hybridization on mechanical properties and autogenous healing of alkali-activated slag-based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125280 (2021).

Ma, R.-Y., Yang, J. & Peng, G.-F. Influence of steel fiber types on residual mechanical properties and explosive spalling of hybrid fiber reinforced ultra-high performance concrete: Optimization and evaluations. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02538 (2023).

Jen, G., Hay, R. & Ostertag, C. P. Multi-scale evaluation of hybrid fiber restraint of alkali-silica reaction expansion in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 211, 1117–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.102 (2019).

Nguyen, D.-L., Thai, D.-K., Tran, N.-T., Ngo, T.-T. & Le, H.-V. Confined compressive behaviors of high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete and conventional concrete with size effect. Constr. Build. Mater. 336, 127382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127382 (2022).

Fu, Z., Yao, Y., Duan, Y., Wang, B. & Li, X. Failure mechanism of bonding between natural fiber and cement matrix at high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 412, 134724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134724 (2024).

Amran, M. et al. Fiber-reinforced alkali-activated concrete: A review. J. Build. Eng. 45, 103638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103638 (2022).

Ni, W. et al. The influence of fiber, aggregate and cementitious materials on the mechanical properties of ultra-high content steel fiber reinforced reactive powder concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 431, 136530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136530 (2024).

Chen, X., Chen, H., Chen, Q., Lawi, A. S. & Chen, J. Effect of partial substitution of cement with dolomite powder on glass-fiber-reinforced mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 344, 128201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128201 (2022).

Murali, G. et al. Combined effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes, steel fibre and glass fibre mesh on novel two-stage expanded clay aggregate concrete against impact loading. Crystals 11(7), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst11070720 (2021).

Zhang, F., Lu, Z. & Wang, D. Working and mechanical properties of waste glass fiber reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 439, 137172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137172 (2024).

Zhang, Y. W., Zhou, C. L., Song, J. X., Li, J. Y. & Gong, Y. F. Foundry waste reutilization: Anti-shrinkage geopolymer based on nano-clay and coal gangue. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136710 (2024).

Wan, Z. M., He, T. S., Chang, N., Yang, R. H. & Qiu, H. P. Effect of silica fume on shrinkage of cement-based materials mixed with alkali accelerator and alkali-free accelerator. J. Mater. Res. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.11.110 (2023).

Xu, Y., Xing, G., Zhao, J. & Zhang, Y. The effect of polypropylene fiber with different length and dosage on the performance of alkali-activated slag mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 307, 124978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124978 (2021).

Li, J., Chen, J., Wan, C. & Niu, J. Flexural toughness and evaluation method of steel fiber reinforced self-compacting lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 277, 122297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122297 (2021).

Liu, R., Wang, H. & Xiao, H. Simulation study on the impermeability improvement effect of cement-based materials with different pore structures. J. Build. Eng. 82, 108237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108237 (2024).

Zhang, T., Ma, B., Wu, S., Jin, Z. & Wang, J. Mechanical properties and hydration process of steel slag-cement binder containing nano-SiO2. Constr. Build. Mater. 314, 125660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125660 (2022).

Wang, Q., Ding, Y. & Randl, N. Investigation on the alkali resistance of basalt fiber and its textile in different alkaline environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 272, 121670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121670 (2021).

Poggemann, L., Thelen, R., Meyer, J. & Dittler, A. Experimental investigation on the change of pull-off force between bulk particulate material and an elastic polymeric filter fiber. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 641, 903–915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2023.03.051 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52308227), the Natural Science Major Research Program Project of Anhui Universities (Grant No. 2024AH040037), and Anhui Housing and Urban-Rural Construction Science and Technology Project, Hefei, Anhui, China (Grant No. 2023-YF127).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qinghu Xu: Writing—review & editing, Methodology. Shuchang Liu: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis. Junjie Qian: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis. Rongsheng Xu: Supervision, Methodology. Wei Ma: Supervision, Methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Q., Liu, S., Qian, J. et al. Effects of three different types of fibers and dosage on the properties of alkali-activated copper slag–slag cementitious materials. Sci Rep 15, 26438 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11384-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11384-1