Abstract

In this study, an e-powertrain for 55 kW electric tractors was designed and analyzed using agricultural workload data. The electric tractor power transmission system structure was analyzed, and three types were selected: the single-motor, the dual-motor, and the dual-motor including a planetary gear set (PGS). The single-motor specification for type I was 62.8 kW at 199.5 Nm. In type II, the power take-off (PTO) motor specification was 55.3 kW at 176.0 Nm, and the traction motor specification was 58.4 kW at 185.3 Nm. In type III, the PTO motor specification was 55.3 kW at 176.0 Nm, and the traction motor specification was 11.8 kW at 37.7 Nm. The power and torque of the single motor of type I were the highest. In type II, both the PTO and traction motor specifications were above those of the 55.3-kW engine. In type III, the PTO motor specifications were identical to those of type II. Moreover, the adoption of the traction motor specification could significantly reduce the required output by 80% compared with that of type II. A comparison of the mechanical components by e-powertrain type showed that the number of mechanical components exhibited the descending order of type II, type III, and type I. Depending on the tractor power, the powertrain structure can be appropriately applied. This study is expected to facilitate future development and optimization of the e-powertrain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the adoption of the Paris Climate Agreement, efforts are made to limit the increase in the global average temperature to below 2 °C by 2100 compared with preindustrial levels to mitigate climate change worldwide, thereby striving to maintain the increase below 1.5 °C1. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) proposed specific goals for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in its 2018 Special Report—Global Warming of 1.5 °C (SR15). To limit the increase in the Earth’s temperature to less than 1.5 °C, GHG emissions must be reduced. A reduction of at least 45% compared with the level during the 2010s is needed by 2030, and emissions should be reduced to net zero by 20502. In addition, the total amount of carbon emissions by 2050 will reach approximately 3000 Gt CO2. Carbon neutrality has become a global concern, and many companies, governments and institutions are accounting for this goal. Business and industrial sectors are focusing on reducing GHG emissions by adopting eco-friendly technologies and green energy sources. In Korea, the GHG reduction policy aims to reduce carbon emissions originating from the agricultural and livestock sector to 9.3 million tons by 20503. Electrification in the field of agricultural machinery is important in response to the high-power consumption and to ensure stability against external shocks and short circuit issues during agricultural operations4. Agricultural machinery is used to perform various agricultural operations, such as plow tillage, rotary tillage, loader operation, and baler operation, in addition to basic driving. Therefore, a substantial amount of power is consumed. Moreover, it is difficult to charge agricultural machinery externally during operations. This necessitates the installation of a battery with a sufficient capacity. In working environments such as paddies and fields, it is necessary to respond to problems such as short circuits owing to shock and moisture inflow issues. In many cases, paddy fields contain standing water, and various crops, such as rice, are grown. Therefore, ensuring safety is necessary. In Korea, various types of policy support instruments are used to ensure the adoption of agricultural machinery electrification technology and establish an initial market. This includes providing subsidies and incentives for replacing existing old agricultural machinery.

In electric tractors, the existing internal combustion engine (ICE) components (engine and powertrain) have been replaced with electric drive systems (motor, inverter, battery, and e-powertrain) that require more space5. Accordingly, the layout of the electric drive system is important, and the e-powertrain composition and structure must be analyzed. There are various types of e-powertrains. The number of motors and power connections typically affect the overall system efficiency and economic feasibility.

In the automotive field, single motors are generally applied to the front and rear wheels when a two-wheel drive (2WD) system is used. However, the power performance is less than that of the all-wheel drive (AWD) system. Because the performance is insufficient when snowy or rough roads cannot be avoided, the AWD system provides an economic advantage as only one motor is employed. The single-motor type encompasses two cases: (1) using one front-wheel motor and (2) using one rear-wheel motor. If two or more motors are installed, the AWD method is applied. The system generally comprises a main driving motor and a lower output auxiliary motor. It is configured to transmit power to the front and rear wheels. Additionally, space is saved by eliminating the propeller shaft of the existing 4WD system. The tri-motor type is similar to the dual-motor type. Notably, one motor supplies power to the front wheels, while two motors supply power to the rear wheels. However, in a particular case, the system was developed to connect to a reducer to transmit power to both wheels. In addition, the front-wheel motors are identical, but there are cases where the two rear-wheel motors separately transmit power to each wheel. This configuration improves driving responsiveness. In the quad-motor type, power is transmitted by connecting a motor to each of the four wheels. Thus, this system can achieve different performance levels depending on the driving environment and can ensure a correspondingly high output. When a quad-motor system is installed, the tank turn function is provided. Similar to a tank rotating 360° in place, each motor controls the rotation direction of the corresponding wheel. This enables 360° rotation in place. In the quad-motor case, the installation of in-wheel motors has been actively studied recently. In contrast to motors generally located at the center of the car body, the motor is installed inside the wheel. This yields a structure where the wheel surrounds the motor. This approach provides the advantages of optimizing the load capability and saving space inside the vehicle and battery6.

Most electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers apply a one-speed transmission (or reducer) system between the motor and wheel7. Only certain manufacturers of high-performance EVs, such as Porsche, have adopted the two-speed transmission system considering high speed and acceleration. In the tractor field, the existing transmission structure is utilized for small tractors by adopting a single-motor type in which the engine has been replaced with an electric motor for rapid commercialization8. At this time, a hydrostatic transmission (HST) system has been developed. It implements a continuously variable transmission function via a hydraulic pump and motor to fully utilize the compact design. This method is considered suitable for small tractors that handle relatively low workloads. There are cases where a dual-motor type has been adopted in medium-sized tractors considering the target speeds for power take-off (PTO) and driving operations. Such tractors can more efficiently perform control adapted to the target speed by configuring the PTO and traction motors9. Recently, the development of an e-powertrain structure using a dual-motor type and a planetary gear set (PGS) has been researched in China10,11,12,13. However, this technology is still at the prototype stage. This system exhibits a power combination and distribution structure that necessitates power characteristics analysis14. However, the motor output can be optimized, and spatial arrangement advantages can be obtained. In Europe, PTO operations were conducted at the front and sides in addition to the rear. Therefore, additional motors may be configured. In addition, the driving axle does not encompass only one axis but can be divided into front and rear axes. Specifically, left and right sides can be distinguished.

The overall goal of this study is to analyze representative types of e-powertrains for agricultural tractors and determine their structure and configuration. For the selected types, the required specifications of the electric motor were calculated on the basis of agricultural workload data, and the characteristics and number of mechanical components of the e-powertrain system were compared and analyzed according to the type. Finally, the e-powertrain type was determined. The specific objectives were to analyze representative e-powertrain types for the agricultural tractor, calculate the required motor specifications according to the selected e-powertrain types, compare the characteristics and number of mechanical components of the e-powertrain system according to the considered types, and determine the optimal e-powertrain type and configuration for the agricultural tractor.

Methods

Electrification

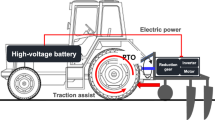

A diesel engine tractor includes devices to reduce exhaust gases such as carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HCs), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter (PM). The types of exhaust gas reduction devices employed are exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), selective catalytic reduction (SCR), diesel particulate filter (DPF) and other devices according to tier regulations. The electric drive system comprises an electric motor, inverter, battery, e-powertrain, etc. In addition, it contains necessary EV components, such as a battery management system (BMS), electric vehicle communication controller (EVCC), power distribution unit (PDU), low-voltage DC‒DC converter (LDC), and onboard charger (OBC). An important consideration when developing electric tractors is the layout within the limited space. The number of parts needed for electric drive systems is greater than that for ICE tractors. The placement of parts becomes important during the design of electric tractors.

Figure 1 shows an illustrative schematic of ICE tractor power flow. Notably, engine power is largely transmitted to the PTO motor, driving axle and hydraulic system, and PTO power is transmitted directly. Driving axle power is transmitted through the transmission system, and the power of hydraulic devices such as three-point hitches and steers is transmitted through the main pump or sub pumps. Therefore, even when designing electric tractors, the power transmission system can be configured in various ways depending on the number of motors and the connection configuration. In this study, the main power sources of the tractor were selected and analyzed by dividing them into three types: the PTO motor, the driving axle, and the hydraulic system.

e-powertrain

The e-powertrain is configured to transmit power via an electric drive system with a battery, motor, and inverter as the power source rather than a diesel engine. Each electric motor is connected to a driving axle, PTO motor, and hydraulic system.

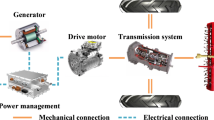

Figure 2 shows representative types of electric drive power transmission systems. In Europe, PTO motors exist for the rear, front, and sides. However, only one was considered for the Korean tractor structure. Although the front and rear axles can be separated, they were designed to comprise only one driving axle. The number of motors ranges from one to three depending on the driving axle, PTO motor, and hydraulic pump connections. Notably, (a) shows the case in which one motor is used, (b)–(d) show the case in which two motors are employed, and (e)–(j) show the case in which three motors are used. Because limited motor specifications can be selected and analyzed, cases (b), (e), and (f) were chosen and investigated. In most e-powertrain types, the motor of the hydraulic system for steering and for lifting and lowering the three-point hitch is configured separately. The gear pump is always driven at the rated rotational speed. When connected to the driving axle motor or the PTO motor, a gear pair should be added. This makes it difficult to save space. Accordingly, the motor of the hydraulic system was considered a separate configuration. The corresponding structures are shown in (b), (e), (f), and (i). However, the structure shown in (i) was determined inefficient and excluded because it combined a motor in parallel with a hydraulic system with a relatively low motor output.

Various motor types were selected for calculating the required motor specifications and analyzing the characteristics, as shown in Fig. 3. Type I consists of a single motor. In this type, power is transmitted from one motor to the driving axle and PTO motor. Type II consists of dual motors, and power is transmitted to the driving axle and PTO motor. Type III is identical to type II in that it comprises dual motors, but power summation and splitting are enabled through the adoption of a PGS. In all types, the hydraulic system was designed to be driven by a separate motor.

Figure 4 shows a schematic of type I. This type represents an engine–electric motor replacement method. The power of the electric motor is transmitted to the driving and PTO axles. The ICE powertrain is applied equally between the input shaft of the electric motor and the output shaft of the driving and PTO axles. This structure was developed by John Deere, Kubota, Solectrac, and Monarch for small tractors that perform agricultural operations involving low loads. It was rapidly developed by applying the ICE powertrain to the existing tractor line-up.

Figure 5 shows a schematic of type II. In this type, the PTO and traction motors are used separately. Many geartrain arrangements and clutches are needed to control the tractor and PTO speeds with one motor. In this structure, the required speed range can be efficiently controlled because power is transmitted separately to the driving and PTO axles. Tractors use more than 80% of the engine rated power for the driving and PTO axles during high-load agricultural operations such as plow tillage, towing operation, and rotary tillage. Type II is suitable for medium-sized tractors of 40 kW or more. Kubota, Daedong, and TYM have developed dual-motor-type electric tractors.

Figure 6 shows a schematic of type III. This dual-motor type is similar to type II. However, power is coupled and distributed through a PGS according to the working mode. The power flow of type III is shown in Fig. 7 according to the power summation and split modes. In the power summation mode, the power outputs of the PTO and traction motors are combined and transmitted to the driving axle. This mode is used for high-load operations such as high-speed driving operations, plow tillage, and towing operations. In the power split mode, the power outputs of the PTO and traction motors are transmitted to the PTO and driving axles, respectively. This mode is used for PTO operations such as rotary tillage. An electric tractor with this structure has recently been developed into a prototype at universities and research institutes in China. In addition, e-powertrains with dual motors and a PGS are actively studied.

Agricultural workload data

The workload data, such as the engine, driving axle, and PTO workload data, were plotted as a T–N curve to calculate the motor specifications needed for the different e-powertrain types. The workload data used in the analysis were extracted from previous research15. The data were measured using a 55-kW diesel engine tractor of the same output, and field experiments were conducted on the main agricultural operations such as plow tillage, rotary tillage, and driving operation in Korea. Torquemeters were installed on the axle and PTO, and the torque generated on the axle and PTO was measured through plow and rotary tillage. At this time, the axle torque was calculated as the sum of four wheels. The measured data were converted into a T–N curve and analyzed according to the type of power transmission system.

Figure 8 shows the T–N curve of the measured engine data of a 55-kW agricultural tractor during agricultural operation. During plow tillage, the engine speed ranged from 939 to 2328 rpm, and the maximum torque was 191 Nm. During rotary tillage, the engine speed ranged from 1922 to 2328 rpm, and the maximum torque was 199 Nm. During driving operation, the engine speed ranged from 640 to 2300 rpm, and the maximum torque was 219 Nm. Accordingly, during agricultural operation, the engine speed ranged from 640 to 2328 rpm, and the engine torque ranged from 3 to 219 Nm. The detailed engine data, which are used for calculating the required motor specifications, are listed in Table 1.

Figure 9 shows the T–N curve of the measured driving axle data of the 55-kW agricultural tractor during agricultural operation. During plow tillage, the axle torque ranged from 65 to 21,062 Nm, and the maximum speed was 19 rpm. During rotary tillage, the axle torque ranged from 85 to 6892 Nm, and the maximum speed was 17 rpm. During driving operation, the axle torque ranged from 72 to 8070 Nm, and the maximum speed was 118 rpm. Accordingly, the axle torque during agricultural operation ranged from 65 to 21,062 Nm, and the maximum speed reached 118 rpm. The detailed driving axle data, which are used for calculating the required motor specifications, are listed in Table 2.

Figure 10 shows the T‒N curve of the measured PTO data of the 55-kW agricultural tractor during agricultural operation. The PTO speed during rotary operation ranged from 559 to 581 rpm, and the PTO torque ranged from 120 to 636 Nm. The average PTO torque reached 476 Nm at the L3 gear stage and 414 Nm at the L4 gear stage. Notably, a higher torque occurred at the L3 gear stage than at the L4 gear stage. Because the PTO gear stage was set to stage 1, the PTO speed was similar at both the L3 and L4 gear stages, with an average PTO speed of 570 rpm. The detailed PTO data, which are used for calculating the required motor specifications, are listed in Table 3.

Methodology

Motor T‒N curves for each type were generated via load data measured during agricultural operations. When electrifying an existing power transmission system, an increase in the gear ratio can reduce the motor specifications. Conversely, a reduction in the gear ratio results in an increase in the motor specifications. In this study, motor specifications similar to those for the existing ICE powertrain gear ratio were selected.

Figure 11 shows the calculation process for the required motor specifications according to the e-powertrain type. The type I T‒N curve was generated by including driving axle and PTO data. Accordingly, when data summation and the gear ratio were applied, the curve was similar to that of the engine data and was selected accordingly. The type II T‒N curve was selected on the basis of the gear ratio applied to the driving axle and PTO data. The T‒N curve of the traction motor was generated on the basis of axle data collected during plow tillage. The T‒N curve of the PTO motor was used as a source for PTO data during rotary tillage. For dual-motor types II and III, the gear ratio connected to the PTO motor was set to the existing PTO gear ratio, and the gear ratio connected to the traction motor was set to enable the application of a spiral bevel gear and final reduction gear, except for the main shift and range shift. The torque and speed of the PTO and traction motors were calculated via Eqs. (1)–(4). The PTO gear ratio is calculated as 4, the gear ratio of the range shift is calculated as 5.7, and the gear ratios of the spiral bevel gear and final reduction gear are calculated as 3.2 and 10.2, respectively. The gear ratio was set based on an engine tractor with the same output. In addition, the efficiency of the PTO axle to the engine and the driving axle to the 4WD axle were calculated considering the number of gear pairs. At the time, the efficiency of the helical gear was applied as 0.98, and as a result, \({\eta }_{PTO}\) of 0.94 and \({\eta }_{DA}\) of 0.92 were applied.

Type III was configured to transmit power to the driving and PTO axles through the brake during PTO operation and to the axle through power combination during driving and towing operations. Therefore, the T‒N curve of the PTO motor was selected to match that of type II. The T‒N curve of the traction motor was selected to satisfy the axle data during rotary tillage. The curve was finally verified by examining whether the combined torque of the PTO and traction motors satisfied the driving axle data during plow tillage.

where \(T_{PM}\) is the torque of the PTO motor (Nm), \(N_{PM}\) is the speed of the PTO motor (rpm), \(\eta_{PTO}\) is the efficiency of the PTO axle to the engine (%), \(GR_{PTO}\) is the gear ratio of the PTO axle to the engine, \(T_{PTO}\) is the torque of the PTO axle (Nm), and \(N_{PTO}\) is the speed of the PTO axle (rpm).

where \(T_{TM}\) is the torque of the traction motor (Nm), \(N_{TM}\) is the speed of the traction motor (rpm), \(\eta_{DA}\) is the efficiency of the driving axle to the 4WD axle, \(GR_{DA}\) is the gear ratio of the driving axle to the 4WD axle, \(T_{DA}\) is the torque of the driving axle (Nm), and \(N_{DA}\) is the speed of the driving axle (rpm).

Results

Type I

Figure 12a shows the T‒N curve of type I to satisfy the engine data. The required specifications for a single motor of type I were 68.8 kW of power and 218.9 Nm of torque. The performance curve for the type I motor torque and power at the rated speed of 3000 rpm is shown in Fig. 12b.

In type I, an ICE powertrain is applied. In addition, it is an independent PTO type and enables PTO operation regardless of whether it is driven. Additionally, it operates at the rated speed of the provided single motor, and the vehicle speed is determined according to the gear stage. A clutch is necessary because power is transmitted from one motor to the driving and PTO axles. Because the engine has been replaced by a motor, existing powertrains can be used, and mass production can be achieved rapidly.

Type II

Figure 13a shows the T‒N curve for the PTO motor of type II to satisfy the PTO data. The required specifications for the PTO motor of type II were 58.4 kW of power and 185.3 Nm of torque. The performance curve for the torque and power of the type II motor at the rated speed of 3000 rpm is shown in Fig. 13b.

Figure 14a shows the T‒N curve for the traction motor of type II to satisfy the driving axle data. The required specifications for the traction motor of type II were 55.3 kW of power and 176.0 Nm of torque. The performance curve for the torque and power of the type II motor at the rated speed of 3000 rpm is shown in Fig. 14b.

In type II, motor power is transmitted separately to the driving and PTO axles. Accordingly, the required vehicle and PTO speeds can be efficiently controlled. In addition, the number of mechanical components can be reduced owing to the simple structure of the connected motor-reducer. This structure is convenient to assemble and repair. There is an advantage in that reverse driving and PTO operations can be implemented without a separate geartrain by using reverse motor rotation. The capacity of the two motors exceeds 55 kW. The two motors occupy a certain amount of space. Mass production is moderately difficult because the motor size is large and the housing is difficult to manufacture.

Type III

Because all the loads occurring on the PTO axle are handled by the PTO motor, the specifications of the PTO motor for type III are identical to those for type II. Figure 15a shows the T‒N curve for the traction motor of type III to satisfy the driving axle data. The required specifications for the traction motor of type III were 11.8 kW of power and 37.7 Nm of torque. The performance curve for the torque and power of the type II motor at the rated speed of 3000 rpm is shown in Fig. 15b.

Figure 16 shows the T–N curve combining PTO and traction motors for type III vehicles during high-load operations, such as high-speed driving, plow tillage, and towing operations. The driving axle data of plow tillage are located higher than the T‒N curve of the PTO motor for type III. However, these are located within the T‒N curve when combining the PTO and traction motors for type III. Accordingly, the combined power of the PTO and traction motors may satisfy the workload of the driving axle during plow tillage.

As this type including a PGS, it is necessary to consider the power summation and split modes depending on the working mode according to the agricultural operations. Additionally, power characteristics such as power circulation should be analyzed. When power circulation occurs, the efficiency decreases within a certain speed range. Space can be saved by reducing the traction motor capacity through power combination and control. When combining and distributing power, the mechanical components of the clutch and brake should be installed in the motor and the PGS ring gear. Type III can be configured in two modes, namely, power summation and split modes. In the power summation mode, the power outputs of the PTO and traction motors are combined and transmitted to the driving axle. This mode is suitable for high-load operations, such as high-speed driving, plowing tillage, and towing operations. In the power split mode, the power of the PTO and traction motors is distributed separately to the driving and PTO axles and is used for PTO operations such as rotary tillage. In type III, the vehicle speed is controlled by setting the PTO motor speed to the PTO operation speed and defining the traction motor speed range. Additionally, type III can perform reverse driving and PTO operations without a separate geartrain by using reverse motor rotation similar to type II. In this study, the specifications of the electric motor were determined based on agricultural workload requirements, with the rated rotational speed set at 3000 rpm. This speed was selected in reference to common standards used by Korean motor manufacturers. Depending on the operational range, the efficiency can be further improved by selecting an appropriate motor specification.

Comparison of motor specifications and characteristics

Table 4 provides a comparison of the motor specifications by e-powertrain type. In type I, the single-motor specification was determined as 68.8 kW at 218.9 Nm. In type II, the PTO motor specification was 55.3 kW at 176.0 Nm, and the traction motor specification was 58.4 kW at 185.3 Nm. In type III, the PTO motor specification was 55.3 kW at 176.0 Nm, and the traction motor specification was 11.8 kW at 37.7 Nm. The single-motor power and torque of type I were the highest. The specifications of the PTO and traction motors were above 55.3 kW for type II. The PTO motor specifications of type III motors were identical to those of the type II motors. The traction motor specification needed for type III was significantly lower than that needed for type II.

Figure 17 shows the results of comparing the diesel engine power with the motor power for each e-powertrain type. The ICE of the 55-kW tractor exhibits a rated torque of 240 Nm and is indicated by a red line. The single-motor power of type I increased by 24.4%, and the torque decreased by 8.8%. The PTO motor power of type II was identical, but the torque increased by 26.7%. The traction motor exhibited a 5.6% increase in power and a 26.7% decrease in torque. The PTO motor of type III was identical to that of type II. The traction motor showed a 78.7% decrease in power and an 84.3% decrease in torque.

When transitioning from an ICE to an electric motor, the capacity of the electric motor can be adjusted according to the tractor performance target. It is also very important to review whether the capacity needs to be increased. It has been shown that electric tractors require an electric motor that can provide more torque than an ICE, and this is because the workload data is positioned within the continuous T–N curve of the motor, and only high loads during agricultural work are responded to with the maximum T–N leading capacity. In type I, the existing ICE transmission was applied, and it is judged that the required output increased the most due to the difference in the performance curves of the engine and motor. In type II, the PTO motor was the same, but the required output also increased in the traction motor.

The PTO motor of type III is identical to that of type II. The traction motor showed a 78.7% decrease in power and an 84.3% decrease in torque. It was demonstrated that the traction motor of type III can be reduced by 80% from 58.4 to 11.8 kW and from 176 to 38 Nm, compared with the traction motor of type II. The motor torque is related to the magnetic flux density, current, and coil. If the number of turns is increased or the winding radius is increased substantially, the motor size increases. As a result, the reduction in the required motor torque allows for a more compact size. This is advantageous for securing space while designing an e-powertrain.

Figure 18 shows the power transmission configuration according to e-powertrain type. The power transmission configuration was considered, excluding the 4WD and front axle parts. Type I comprises an ICE powertrain with an equal output. It includes forward and reverse gears, a PTO clutch, and a range shift. Types II and III are dual-motor types. Notably, reverse PTO and driving operations can be performed via reverse motor rotation. Type II exhibits a range shift of seconds to satisfy the agricultural workload. Type III requires mechanical components capable of fixing the PGS to implement the power coupling and split modes. Accordingly, a clutch and brake were added to the PGS ring gear.

The number of mechanical components and characteristics of the e-powertrain according to type were analyzed. Details are provided in Table 5. The numbers of gears were 36 (type I), 17 (type II), and 27 (type III), and the numbers of bearings were 32 (type I), 14 (type II), and 26 (type III). For type I, the number of clutches was three for the PTO motor, front shift, and rear shift. For type II, there were three clutches, namely, one for the PTO motor and two for the range shifts. For type III, there were two clutches, namely, one for the PTO motor and one for the PGS ring gear, and it contained one brake to fix the ring gear of the PGS.

The number of mechanical components, such as gears, bearings, clutches, and brakes, decreased in the following order: type II, type III, and type I. Type I encompassed 24 gear stages. It comprised a main shift for the fourth gear, a range shift for the third gear, and creep for the second gear. Type II comprised a range shift for the second gear. This type provides two modes, namely, the power summation and split modes.

Conclusions

In this study, motor specifications were determined, and the characteristics were analyzed according to the electric tractor e-powertrain structure. Utility tractors and tractor e-powertrains have not been mass produced worldwide. Recently, R&D has been actively conducted. Because various advantages and disadvantages can be obtained depending on the e-powertrain structure, it is difficult to determine which type is better at this stage. In addition, in this study, it was assumed that the hydraulic pump power was configured separately. In many cases, the power for the driving axle, PTO motor, and hydraulic pump is configured in conjunction. Accordingly, research on e-powertrain structural analysis and optimization is necessary for the development and mass production of electric tractors. The main results are as follows:

Representative types of electric tractor e-powertrains were analyzed. Among the eight representative types, three types of motors and connection types were selected for the tractor main power source, such as the engine, driving axle, hydraulic pump, and PTO motor. At this time, the motor for the hydraulic system was configured separately because it is generally driven continuously at the motor rated speed through the connection of a gear pump. In addition, the motor for the hydraulic system requires less power. Therefore, it was excluded from the parallel connection structure.

The required motor specifications were analyzed for the type I (single motor), type II (dual motor), and type III (dual motor and PGS) motors. The selected types were electric tractor e-powertrain types developed by tractor companies.

An analysis of the required specifications via the measured load data revealed that the single-motor specification for type I was 62.8 kW at 199.5 Nm. In type II, the PTO motor specification was 55.3 kW at 176.0 Nm, and the traction motor specification was 58.4 kW at 185.3 Nm. In type III, the PTO motor specification was 55.3 kW at 176.0 Nm, and the traction motor specification was 11.8 kW at 37.7 Nm. The power and torque of the single motor of type I were the highest. In type II, both the PTO and traction motor specifications were above those of the 55.3-kW ICE. In type III, the PTO motor specifications were identical to those of type II. Moreover, the adoption of the traction motor specification could significantly reduce the required output by 80% compared with that of type II. A comparison of the mechanical components by e-powertrain type revealed that the number of mechanical components, such as gears, bearings, clutches, and brakes, exhibited the descending order of type II, type III, and type I. Depending on the tractor power, the powertrain structure can be appropriately applied. This study is expected to facilitate future design and optimization of the e-powertrain.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author, [Y.J.K.], on reasonable request.

References

NAIR (National Air Emission Inventory and Research). Handbook of Estimation Methods for National Air Pollutant Emissions (IV) (2020).

NAIR (National Air Emission Inventory and Research). 2017 National Air Pollutant emissions (2020).

KAMICO, KSAM. Agricultural Machinery Yearbook in Republic of Korea, Korea Agricultural Machinery Industry Cooperative and Korean Society for Agricultural Machinery (2023).

Mocera, F. & Somà, A. Analysis of a parallel hybrid electric tractor for agricultural applications. Energies 13(12), 3055. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13123055 (2020).

Tong, Y., Zhang, J., Xu, L. & Yan, X. Driving system design and power source parameter optimization of tractor with dual-motor coupling drive. World Electr. Veh. J. 14(3), 63 (2023).

Troncon, D. & Alberti, L. Case of study of the electrification of a tractor: Electric motor performance requirements and design. Energies 13(9), 2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13092197 (2020).

Zhang, X. Design theory and performance analysis of electric tractor drive system. Power 3(18), 20 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Design matching and dynamic performance test for an HST-based drive system of a hillside crawler tractor. Agriculture 11(5), 466 (2021).

Mocera, F., Somà, A., Martelli, S. & Martini, V. Trends and future perspective of electrification in agricultural tractor-implement applications. Energies 16(18), 6601 (2023).

Deng, X. et al. Research on dynamic analysis and experimental study of the distributed drive electric tractor. Agriculture 13(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13010040 (2023).

Xie, B. et al. Design and hardware-in-the-loop test of a coupled drive system for electric tractor. Biosyst. Eng. 216, 165–185 (2022).

Mao, Y., Wu, Y., Yan, X., Liu, M. & Xu, L. Simulation and experimental research of electric tractor drive system based on Modelica. PLoS ONE 17(11), e0276231 (2022).

Chen, Y., Xie, B., Du, Y. & Mao, E. Powertrain parameter matching and optimal design of dual-motor driven electric tractor. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 12(1), 33–41 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Design and optimization of dual-motor electric tractor drive system based on driving cycles. PLoS ONE 18(6), e0286378 (2023).

Baek. S. M. Design and power analysis of a dual-motor e-powertrain with compound planetary Geartrain for a 55-kW electric tractor. Doctoral dissertation (Chungnam National University, 2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry (IPET) through the Eco-friendly Power Source Application Agricultural Machinery Technology Development Program, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (322047 and 322046).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.M.B. and Y.J.K.; Methodology: H.H.J.; Investigation: W.S.K.; Data analysis: Y.S.K.; Writing—original draft preparation: S.M.B.; Writing—review and editing: S.M.B. and Y.J.K.; Visualization: S.M.B.; Supervision: Y.J.K. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baek, SM., Jeon, HH., Kim, WS. et al. Design and analysis of a power transmission system for 55 kW electric tractor using agricultural workload data. Sci Rep 15, 28028 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11444-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11444-6