Abstract

It is unclear whether the serum glucose-to-potassium ratio (GPR) is related to delirium in critically ill patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between GPR and delirium in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). Patients were enrolled from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV). We extracted the mean values of blood glucose and blood potassium on the first day of admission to the ICU and calculated the glucose-to-potassium ratio using Navicat Premium (16.0). In this study, known risk factors for delirium, including age, sex, duration of mechanical ventilation, benzodiazepine use, opioid use, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), were systematically adjusted through a multivariable logistic regression model. Subgroup analysis was used to determine the risk factors for delirium in critically ill patients. Of the 15,007 patients, 56.2% were males, the median age was 65 years, and the overall incidence of delirium was 16.8% (2528/15007). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that an increased GPR was significantly associated with increased delirium occurrence. The Model 3 adjusted odds ratio for the GPR as a continuous variable was 1.17 (95% CI 1.09–1.26). Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 was adjusted for comorbidities; and Model 3 included clinical, laboratory, and treatment variables. Additionally, the incidence of delirium increased significantly with an increasing GPR (trend test: 1.1 (1.05–1.15); p < 0.01). GPR is an independent predictor of delirium in critically ill ICU patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Delirium is an acute disorder of attention and cognition and is linked to underlying physiological disorders1. It is also an independent predictive factor for mortality and several morbidities, such as extended lengths of stay in the ICU and hospital and cognitive dysfunction2. Delirium is common in ICU patients and is associated with adverse outcomes, particularly among those requiring mechanical ventilation3,4. Delirium is typical in patients with acute heart failure and is associated with both short- and long-term mortality in the ICU5,6. Delirium increases the costs and difficulty of posthospitalization rehabilitation. Delirium in critically ill patients is associated with multiple high-risk factors, including nonmodifiable factors (age ≥ 65 years and baseline cognitive impairment) and modifiable triggers (mechanical ventilation, benzodiazepine exposure, and metabolic derangements)7. Specifically, metabolic dysregulation, such as stress-induced hyperglycemia and electrolyte abnormalities, has been shown to significantly increase delirium risk8,9,10. However, the mechanisms underlying delirium remain unclear, making the treatment and management of delirium in the ICU challenging.

However, the mechanisms of delirium are multifactorial and not fully understood. Given the potential to reduce the incidence of delirium, clinical severity, and complications in ICU patients through timely intervention and early prognostic prediction, identifying prognostic markers that accurately predict poor outcomes is important. The GPR, which is calculated as the serum glucose level divided by the serum potassium level, has been recently proposed. The GPR has been shown to have prognostic value for mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury11 and ischemic stroke12,13,14. The GPR also plays an important role or is highly predictive in patients with abdominal trauma15 and acute type A aortic dissection16. The GPR is also a good predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction17 or patients admitted to the coronary care unit18. The GPR is simple, less invasive, cost-effective, and readily applicable in clinical settings, which is why it is becoming increasingly widely used.

Although previous studies have linked the GPR to outcomes in patients with cerebral hemorrhage or brain injury19,20, no studies have specifically investigated its association with ICU delirium. Notably, the incidence and mechanism of delirium differ significantly across different critical illnesses; delirium occurs independently of age in patients with acute heart failure and may be directly related to insufficient cerebral perfusion due to ventricular remodeling5. The risk of delirium after extracorporeal circulation is as high as 50% and mainly originates from systemic inflammatory storms induced by extracorporeal circulation21, and delirium in patients with severe brain injury is both a result of disruption of the blood‒brain barrier and a secondary cerebral predictor of dysfunction22. This evidence suggests that delirium of different etiologies may involve heterogeneous pathological pathways, and universal biomarkers are urgently needed for its early detection. We hypothesized that an elevated GPR could be independently associated with delirium in critically ill patients. We used the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database 23 to investigate the relationship between the GPR and delirium in critically ill patients in the ICU.

Results

Patient characteristics

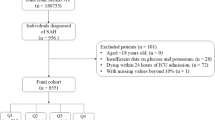

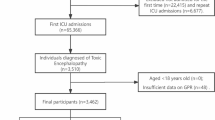

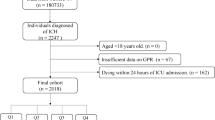

From an initial cohort of 50,920 patients with a first ICU admission, 23,726 patients remained after excluding those with an ICU length of stay of less than 48 h. Following exclusion of patients without a CAM-ICU assessment (4950), with fewer than three blood glucose measurements (2739), with missing potassium data (122), and with dementia (908), the final study population that met all the inclusion criteria comprised 15,007 patients. Figure 1 shows the patient selection process from the MIMIC-IV database. Baseline characteristics according to the quartiles of the GPR are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 65 years, and 8438 (56.2%) patients were males. In the present study, according to the quartiles of the GPR, namely, Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4, the ICU patients were divided into four groups (< 1.3, 1.3–1.6, 1.6–2.0 and > 2.0), with 3740, 3785, 3823 and 3819 patients, respectively. Along with the elevated GPR, the incidences of all comorbidities, except CPD, PVD and TBI, significantly increased. With an increased GPR, patients often required more benzodiazepines or hormones, and the use of insulin was also more common. Among the patients with diabetes, 52.2% had a GPR > 2.0. Delirium occurred in 2528 patients (16.8%). The incidence of delirium in the low GPR group was 560 (15%), and that in the high GPR group was 724 (19.8%). The in-hospital mortality rate was 11.4%, which was significantly higher in the Q4 group (13.8%) than in the Q1 group (11.9%). The length of the hospital stay significantly increased with the increasing GPR (9.6 (6.3, 15.8) vs. 10.5 (6.8, 17.7), p < 0.001), as did the length of the ICU stay (4.0 (2.9, 6.4) vs. 4.2 (2.9, 7.7), p < 0.001).

Relationship between the GPR and delirium

Univariate regression analysis revealed that the HR, MBP, RR, SpO2, the levels of Hb, BUN, creatinine, and sodium, MI, PVD, CVD, CPD, ICH, AHF, liver disease, malignant cancer, medical treatment, urgent surgery, the use of MV, norepinephrine, insulin, statins, benzodiazepine, dexmedetomidine, and opioids and SAPS II were significantly associated with delirium (Supplementary Table 1). The linearity of the relationship between the GPR and delirium was assessed using restricted cubic splines. A linear relationship was observed between the GPR and delirium (Fig. 2). A higher GPR was associated with an increased incidence of delirium. After adjusting for confounders, the GPR was found to be positively associated with delirium in all three models (Table 2). Regardless of whether the GPR was analyzed as a continuous variable or a quartile, the odds ratios (ORs) of the GPR were consistently significant in all three models. An adjusted logistic model was used to reduce the impact of confounding variables. In the fully adjusted logistic model (Model 3), when the GPR was used as a continuous variable, the incidence of delirium increased by 17% for every 1 unit increase in the GPR (OR 1.17, 95% CI: 1.09–1.26). When the GPR was used as a categorical variable in Model 3, the adjusted ORs were 1.29 (95% CI: 1.13–1.47) and 1.35 (95% CI: 1.19–1.53) in Model 2 and the fully adjusted Model 3, respectively, with quartile 1 as a reference (Table 2).

Subgroup analyses and the sensitivity analysis

Subgroup analyses were performed to ensure the stability of the study outcomes. The risk stratification value of the GPR for delirium was further analyzed in multiple subgroups of the enrolled patients, which were stratified by age, diabetes status, benzodiazepine use, dexmedetomidine use and the CCI (Fig. 3). The GPR was significantly associated with a greater risk of delirium in the patients in the age ≥ 65 years and the CCI ≥ 5.7 subgroups, in those without diabetes and those without dexmedetomidine use. Significant interactions were detected in the subgroups with or without benzodiazepine use (P for interaction < 0.05). The predictive value of the GPR for delirium risk was greater in patients without benzodiazepine use (Table 3).

In addition, we performed a sensitivity analysis for patients who underwent urgent surgery or medical treatment. This analysis was performed in the same manner as for critically ill patients in the ICU. Covariate selection for the patients who underwent urgent surgery was based on p < 0.05, as shown in Supplemental Table 2. After adjusting for the full model, the analysis revealed that when the GPR was used as a continuous variable, the incidence of delirium increased by 26% for every 1 unit increase in the GPR (OR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.08–1.46). When the GPR was used as a categorical variable in Model 3, the adjusted ORs were 1.7 (95% CI: 1.31–2.1) and 1.56 (95% CI: 1.18–2.06) in Model 2 and the fully adjusted Model 3, respectively, with quartile 1 as a reference (Supplemental Table 3). Covariate selection for patients who underwent medical treatment was based on p < 0.05, as shown in Supplemental Table 4. In the fully adjusted Model 3, the adjusted ORs were 1.17 (95% CI: 1.07–1.28) and 1.23 (95% CI: 1.05–1.44) when the GPR was used as a continuous variable and a categorical variable, respectively (Supplemental Table 5).

Discussion

In this retrospectiveal o sndct on the MIMIC-IV lnkota, we found a linear relationship between the GPR and delirium incidence. A higherionGPR was liinuked to a grudrdeetmentf delirium. Notably, evene after adjusting for potential confounding factors, the GPR remained robustly linked to delirium. As the GPR increased, patients tended to have more comorbidities and more severe illness. The lengths of the hospital and ICU stays were considerably longer in patients with higher GPRs than in those with lower GPRs. Subgroup analyses revealed that the predictive performance of the GPR was stronger in patients who did not use benzodiazepines. Sensitivity analyses also indicated that elevated GPR was linked to the onset of delirium, regardless of whether the patient was in the stressful situation of emergency surgery or under medical treatment.

Serum glucose and potassium are two important circulating biomarkers for disease prognosis. Hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia are associated with ICU delirium in critically ill patients24,25. The pattern of glucose metabolism in critically ill patients is significantly different from that in patients with diabetes. Glycemic abnormalities are common in ICU patients, and the stress response can increase blood glucose levels in critically ill patients by regulating hormones (glucagon, catecholamines, growth hormone, and cortisol) to provide sufficient energy for organ survival26. Postoperative metabolic disturbances and electrolyte imbalances, especially hyperglycemia and low potassium levels, are closely related to the development of delirium after CABG and need to be considered more carefully10. The glucose-to-potassium ratio (GPR) has recently been widely used in clinical practice and is an independent risk factor for the severity and 6-month prognosis of acute traumatic spinal cord injury27. Early on, the GPR was used in patients with cerebral hemorrhage28 or brain injury11 as a predictor of short-term mortality and a preliminary marker of cerebral dysfunction19. However, the association between the GPR and delirium has not been studied. Our findings suggest a robust association between the elevated GPR and delirium, even after adjusting for confounders. Sedative medications are often administered to patients in the ICU, and the relationship between benzodiazepine use and delirium is still somewhat controversial29,30. Our subgroup analysis revealed that the GPR had a stronger prognostic effect in patients who did not receive benzodiazepines.

The occurrence of ICU delirium is related to many factors, such as patients’ comorbidity with hypertension, smoking, alcohol consumption, and other predisposing factors, such as mechanical ventilation or sedative drugs in the ICU and a prolonged ICU stay7. However, variables such as smoking and alcohol use were not available in the dataset and may act as residual confounders. Although the exact mechanism of delirium is unclear, some studies have suggested that energy metabolism is one of the mechanisms by which delirium, hypoglycemia, or insulin resistance can reduce energy in the brain, causing hypoxia31. Additionally, inflammation and oxidative stress may trigger delirium9. Stress-induced hyperglycemia commonly occurs in patients admitted to the hospital, especially patients in the ICU32, and can lead to a state of insulin resistance. This leads to elevated levels of catecholamines, cortisol, glucagon and growth hormone. Additionally, increases in the levels of inflammatory cytokines further worsen the metabolic milieu. The regulation of sodium/potassium ATPase activity by high catecholamine levels and insulin secretion leads to potassium influx33. In addition, high cortisol levels activate the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system to lower serum potassium levels34. These pathophysiological alterations collectively promote the onset and progression of cerebrovascular disorders and culminate in adverse clinical outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, the MIMIC-IV database may have incomplete preadmission baseline information, such as specific data on the preoperative cognitive status, psychiatric history, and education level, which may influence the occurrence of delirium. Second, we selected only patients who met the diagnostic criteria for the CAM-ICU but could not determine the evaluation time and frequency of the CAM-ICU. Third, glucose measurements were not continuous, and the frequency of measurements varied between patients because of differences in disease severity and dietary composition; Persistent elevation of GPR, an early metabolic indicator, may be associated with disease progression. This limitation may have introduced measurement bias and attenuated the observed associations. Future studies could explore this association in depth using time-dependent covariate modeling with the help of a better longitudinal database. Fourth, this study was a single-center, retrospective cohort study, which warrants further investigation in multicenter randomized controlled trials.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that the GPR was strongly associated with delirium in critically ill patients. The GPR is a good predictor of delirium in critically ill patients in the ICU. Monitoring the GPR could provide information for delirium management strategies. However, additional research is needed to explore whether effective management of the GPR can lead to improved clinical outcomes and prognoses in patients.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective cohort study was based on the MIMIC-IV database (version 2.2), a public clinical database that contains data on patients admitted to the intensive care unit at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, between 2008 and 2019. One author (JLX) obtained the necessary authorization to access the anonymized dataset and oversaw the rigorous process of data extraction. Informed consent was not required because all the patient data in the database were anonymized.

Study population and data extraction

Data from all patients admitted to the ICU for the first time were extracted from the MIMIC-IV database (version 2.2). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) adult patients (≥ 18 years old) admitted to the ICU for the first time; (ii) ICU stay ≥ 48 h; and (iii) presence of CAM-ICU assessment records. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) had a history of baseline dementia; (ii) had fewer than 3 blood glucose tests within 72 h of admission; and (iii) lacked potassium data. The extracted data included (1) demographics (age and sex); (2) vital signs (mean blood pressure (MBP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), and oxygenated hemoglobin saturation (SpO2)); (3) laboratory results (white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin (Hb), creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), potassium, sodium, and calcium levels and average blood glucose level); (4) comorbidities (diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease (CPD), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), malignant cancer, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), chronic heart failure (CHF), myocardial infarction (MI), traumatic brain injury (TBI), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), acute heart failure (AHF), liver disease and renal disease, medical treatment, urgent surgery or elective surgery); (5) the use of mechanical ventilation (MV) and norepinephrine and other drugs (insulin, statins, benzodiazepine, dexmedetomidine, corticosteroids, and opioids) during the ICU stay; (6) scores: the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI); and (7) outcomes: the incidence of delirium, the length of ICU stay, the length of hospitalization and in-hospital mortality. The analysis relied on laboratory values and scores that indicated disease severity and were collected during the first examination within 24 h after ICU admission.

Glucose measurement and GPR definition

We calculated the mean blood glucose (MBG) and potassium levels on the first day during the ICU stay by using all laboratory records for each included patient. The GPR was calculated by dividing the glucose level by the potassium level (mmol/L). The laboratory examination results were recorded in the MIMIC-IV database (version 2.2) “mimic-hospital, lab events” table. This study stratified participants into quartiles (Q1–Q4) on the basis of their GPR values.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of delirium while the patient was in the ICU, whereas the hospital mortality rate and the lengths of the ICU and hospital stays were the secondary outcomes. Patients were assessed for delirium using the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). The CAM-ICU includes (1) acute onset of illness with marked fluctuations in the state of consciousness; (2) inability to concentrate; (3) disorganization and disorganized thinking; and (4) acute changes in the level of consciousness. When items (1) + (2) + (3) or (1) + (2) + (4) are simultaneously present, the patient is determined to be positive for delirium35.

Statistical analysis

The GPR was used to stratify the observational dataset for this retrospective study. Descriptive analysis of the data was conducted using a normality test. Continuous variables were compared using one-way ANOVA or the nonparametric Kruskal‒Wallis test, whereas nonparametric variables were compared by using the median (interquartile range [IQR]). Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables, which are presented as frequencies (percentages).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine the relationship between the GPR and the incidence of delirium in critically ill patients. Continuous and categorical scales were developed for the GPR. In the three models, the possible confounders were gradually changed. Initially, we considered sex and age (Model 1); subsequently, related comorbidities, such as MI, CVD, PVD, CPD, AHF, ICH, malignant cancer and liver disease, were modified (Model 2); and finally, illness severity ratings (SAPS II and CCI), associated therapies, such as the use of MV and norepinephrine, insulin, statins, benzodiazepine, dexmedetomidine, and opioids, and laboratory tests, including the HR, RR, MBP, and SpO2 and Hb and BUN levels throughout the ICU stay, were adjusted in Model 3. A generalized additive model was used to analyze the relationship between the GPR and the occurrence of delirium. A logistic regression model with adjustments, as in Model 3, was used to fit the splines.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the consistency of the GPR–delirium association across key clinical subgroups and to identify effect modifiers through tests for interaction. All subgroup analyses were based on the multivariable-adjusted model (Model 3). By integrating the two-factor interaction terms in the multivariate logistic regression model, the interaction of the GPR with the variables was determined for the stratification of the delirium incidence rate. The R software (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation) and Free Statistics software version 1.7 were used to perform all the statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Sensitivity analyses were performed on the basis of whether the patient underwent emergency surgery or medical treatment. By screening the mode of hospitalization and the type of surgery, we obtained 9898 patients with medical treatment and 3738 patients with urgent surgery. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were also used to determine the relationship between the GPR and the incidence of delirium in these patients. We performed three modeling adjustments. The included covariates were selected on the basis of the results of one-way analysis of variance, with p < 0.05( Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Table 4).

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2.

Abbreviations

- GPR:

-

Glucose-to-potassium ratio

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MIMIC-IV:

-

Medical information mart for intensive care-IV

- CAM-ICU:

-

Confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit

References

Oh, E. S. et al. Delirium in older persons: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA 318(12), 1161–1174 (2017).

Stollings, J. L. et al. Delirium in critical illness: clinical manifestations, outcomes, and management. Intens. Care Med. 47(10), 1089–1103 (2021).

Girard, T. D. et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (awakening and breathing controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 371(9607), 126–134 (2008).

Vasilevskis, E. E. et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for delirium across hospital settings. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 26(3), 277–287 (2012).

Han, J. H. et al. Delirium and its association with short-term outcomes in younger and older patients with acute heart failure. PLoS ONE 17(7), e0270889 (2022).

Iwata, E. et al. Prognostic value of delirium in patients with acute heart failure in the intensive care unit. Can. J. Cardiol. 36(10), 1649–1657 (2020).

Mart, M. F. et al. Prevention and management of delirium in the intensive care unit. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 42(1), 112–126 (2021).

Song, Q. et al. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and delirium in older hospitalized patients: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 22(1), 277 (2022).

Pang, Y. et al. Effects of inflammation and oxidative stress on postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1049600 (2022).

Shirvani, F., Sedighi, M. & Shahzamani, M. Metabolic disturbance affects postoperative cognitive function in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Neurol. Sci. 43(1), 667–672 (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Usefulness of serum glucose and potassium ratio as a predictor for 30-day death among patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Clin. Chim. Acta 506, 166–171 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. The association between serum glucose to potassium ratio on admission and short-term mortality in ischemic stroke patients. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 8233 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Association between the serum glucose-to-potassium ratio and clinical outcomes in ischemic stroke patients after endovascular thrombectomy. Front. Neurol. 15, 1463365 (2024).

Yan, X. et al. Relationship between serum glucose-potassium ratio and 90-day outcomes of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Heliyon 10(17), e36911 (2024).

Katipoğlu, B. & Demirtaş, E. Assessment of serum glucose potassium ratio as a predictor for morbidity and mortality of blunt abdominal trauma. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi. Derg. 28(2), 134–139 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. The blood glucose-potassium ratio at admission predicts in-hospital mortality in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 15707 (2023).

Shan, L. et al. J-shaped association between serum glucose potassium ratio and prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction with stronger predictive value in non-diabetic patients. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 29965 (2024).

Demir, F. A. et al. Serum glucose-potassium ratio predicts inhospital mortality in patients admitted to coronary care unit. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 70(10), e20240508 (2024).

Demirtas, E. et al. Assessment of serum glucose/potassium ratio as a predictor for delayed neuropsychiatric syndrome of carbon monoxide poisoning. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 40(2), 207–213 (2021).

Alışkan, H., Kılıç, M. & Ak, R. Usefulness of plasma glucose to potassium ratio in predicting the short-term mortality of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Heliyon 10(18), e38199 (2024).

Ho, M. H. et al. Prevalence of delirium among critically ill patients who received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy: A systematic review and proportional meta-analysis. Intens. Crit. Care Nurs. 79, 103498 (2023).

Roberson, S. W. et al. Challenges of delirium management in patients with traumatic brain injury: From pathophysiology to clinical practice. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 19(9), 1519–1544 (2021).

Johnson, A. et al. MIMIC-IV (version 2.2). PhysioNet. Sci. Data 10(1), 1 (2023).

van Keulen, K. et al. Glucose variability during delirium in diabetic and non-diabetic intensive care unit patients: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 13(11), e0205637 (2018).

Liu, S. et al. Potential value of preoperative fasting blood glucose levels in the identification of postoperative delirium in non-diabetic older patients undergoing total hip replacement: The perioperative neurocognitive disorder and biomarker lifestyle study. Front. Psychiatry 13, 941048 (2022).

Singh, M. et al. Effect of glycemic variability on mortality in ICU settings: A prospective observational study. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 22(5), 632–635 (2018).

Zhou, W. et al. Serum glucose/potassium ratio as a clinical risk factor for predicting the severity and prognosis of acute traumatic spinal cord injury. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24(1), 870 (2023).

Jung, H. M. et al. Association of plasma glucose to potassium ratio and mortality after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 12, 661689 (2021).

Wang, E. et al. Effect of perioperative benzodiazepine use on intraoperative awareness and postoperative delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 131(2), 302–313 (2023).

Swarbrick, C. J. & Partridge, J. Evidence-based strategies to reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium: a narrative review. Anaesthesia 77(Suppl 1), 92–101 (2022).

Wilson, J. E. et al. Delirium. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 6(1), 90 (2020).

Vedantam, D. et al. Stress-induced hyperglycemia: Consequences and management. Cureus 14(7), e26714 (2022).

Thier, S. O. Potassium physiology. Am. J. Med. 80(4A), 3–7 (1986).

Back, C. et al. RAAS and stress markers in acute ischemic stroke: preliminary findings. Acta Neurol. Scand. 131(2), 132–139 (2015).

Mottaghi, S. et al. The effect of taurine supplementation on delirium post liver transplantation: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 41(10), 2211–2218 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JLX and HJ designed the study and wrote the manuscript. JHZ modified the manuscript. CCH revised the manuscript. HYX analyzed the data and reviewed the statistical analyses. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The use of the MIMIC-IV database has received ethical approval from the institutional review boards (IRBs) at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Because the database does not contain protected health information, a waiver of the requirement for informed consent was included in the IRB approval. All the data were anonymized and obtained under the MIMIC-IV data usage agreement.

Consent statement

Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center waived the need to obtain informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, H., Zhang, J., Han, C. et al. Association between the glucose-to-potassium ratio and delirium in critically ill ICU patients: a retrospective study. Sci Rep 15, 25949 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11475-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11475-z