Abstract

In future applications of UAVs, the frequent transmission of image data raises significant security concerns, particularly regarding the privacy of facial information. Existing methods for protecting such data are often inadequate, especially in the context of UAVs, which require both high security and efficiency. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a face encryption scheme utilizing a 4D hyperchaotic Chen system and DNA cryptography. First, edge recognition face detection technology is employed to detect facial features, with the corresponding matrix selected for encryption. The eigenvalues of the selected matrix are then extracted and hashed using the SHA-256 hash algorithm to enhance security, generating plain image associated chaotic sequences. These sequences are used for Multi-Dimensional cryptic transformation. By employing plaintext-associated hyperchaotic sequences, ciphertext feedback method and dynamic DNA chain encryption, the proposed face encryption scheme significantly strengthens resistance against cryptographic attacks. Simulations were conducted using MATLAB and the resulting performance evaluation metrics were compared with the current state-of-the-art (SOTA) schemes. Experimental outcomes and security analysis confirm that this face encryption scheme provides robust security and high efficiency, as evidenced by key performance metrics specifically an information entropy value of 7.9992, MSE of 8908.61, PSNR of 8.9619, SSIM of 0.00091, NPCR of 99.7163%, UACI of 33.5671%, demonstrating the robustness of our encryption algorithm against differential attacks, and a key space of\(\:\:{2}^{1024}\), ensuring resistance against brute-force attacks. Thus, the proposed face encryption scheme offers excellent performance and holds promising potential for ensuring face privacy by preventing unauthorized access to facial information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid growth of UAV technology has substantially improved the ability of aerial equipment to collect images, resulting in increasingly diverse and detailed image data1. However, this achievement raises new worries about information security, notably the preservation of facial privacy in digital images. Cryptanalytic attacks on digital images during transmission can result in information hacking, posing a major threat to private information. As a result, privacy protection technology has become an essential component of managing digital images collected by UAVs. Encrypting these images is an important technical solution for protecting sensitive data from potential leaks during network transmission. To solve these issues, several excellent cryptographic systems have been established to protect the privacy of images. Singh J. et al.2 presented image encryption and decryption using symmetric key and MATLAB. Kumar R. et al.3 interpreted images and image encryption mathematically. Yin H. L. et al.4 suggested an effective quantum digital signature technique that employs asymmetric quantum keys achieved by secret sharing, a hash, and a PAD. Furthermore, Youssef M. et al.5 suggested numerous satellite images encryption techniques through S-Box generation.

Furthermore, chaotic systems have become increasingly popular in image encryption. Chaotic systems are defined by destructive and diffusion laws, and they have essential features of irregularity, pseudo randomness and sensitivity to initial standards. As a result, there are several uses of chaotic systems in information safety, confident public services, and cryptography. Image encryption algorithms that utilize chaotic systems are more protected, faster, more sensitive, and more effective than conventional methods. Therefore, there is a lot of room for research on chaotic-based image encryption. Pareek N.K. et al.6 suggested a new encryption technique for images that leverages the preliminary settings of a chaotic system created via an external key established on a logistic map to improve security. The key is updated continually throughout the encryption process. Patidar V. et al.7 presented a non-destructive colored image encryption technique utilizing the logistic map. This approach incorporates two series of arrangement and dispersion in the encryption, using the initial conditions, chaotic map parameters, and iteration computations as part of the encryption key. Wang X. et al.8 suggested an innovative color image encryption algorithm created on a 1D logistic map for key generation. Although these small dimensional chaotic systems have benefits like simplicity, comfort of use and clarity, they are limited in their ability to produce random sequences, which could result in lesser uncertainty and vulnerability to attacks. As our understanding of chaotic systems expands, scholars are turning their attention to higher dimensional chaotic systems rather than old ones. This development has garnered a lot of interest. Cang S. et al.9 built a 4D independent hyperbolic stationary point chaotic map and thoroughly inspected its vibrant behavior, discovering a four dimensional brief chaotic system. El-Damak D. et al.10 suggested hyperchaos and Fibonacci Q-Matrix for medical image encryption. Feng W. et al.11,12 have made notable contributions to hyperchaotic systems in image encryption, utilizing robust polynomial and fractional-order chaotic maps to enhance security, efficiency, and resistance against attacks. Qian K. et al.13 developed a memristor-enhanced polynomial hyperchaotic map for image encryption, demonstrating strong resistance against various cryptographic attacks. A bigger key space is provided by higher-dimensional chaotic systems, which makes decryption more challenging and improves encryption security. The dynamic behavior of the system grows increasingly complex as dimensionality rises, enhancing the encryption effect even more. Because of their extensive dynamic properties, that make it further difficult for foes to expect scheme conditions, Multi-dimensional chaotic systems are more suited for set-ups demanding high safety than low dimensional systems. The proposed face encryption scheme makes extensive use of 4D Hyperchaotic Chen system to enhance security, expand key space, and optimize both encryption and efficiency.

In 2023, Gao S. et al.14 provide a novel image encryption technique. This approach has a good computational efficiency as it only encrypts the face from an image. First, only the face from an image is extracted and identified using facial recognition technology. The encryption algorithm is then used to create cipher-images using techniques like diffusion and permutation. When tested on a dataset, the suggested technique performs admirably. Alexan W. et al.15 proposed encryption technique to secure military images in UAV network. Hadi H. et al.16 performed a thorough analysis of privacy concerns, security, and suggested a new defensive technologies for UAVs in the same year. This paper summarizes important lessons learnt in drone security and privacy, provides viewpoints and insights on the risks and vulnerabilities related to drones, and thoroughly investigates their privacy and security concerns. These investigations demonstrates that the majority of UAV safety communication procedures have produced satisfying outcomes, significantly accelerating advancements in information security.

Cryptanalysis is essential for evaluating the strength and reliability of encryption schemes, aiming to uncover potential vulnerabilities and ensure robust security. Hackers commonly exploit encryption techniques through chosen-plaintext and chosen-ciphertext attacks. Several studies have highlighted vulnerabilities in existing encryption schemes, revealing their susceptibility to various attacks. Wen H. et al.17 demonstrated weaknesses in a quantum chaos and DNA encryption scheme, while their earlier work in 202318 analyzed security flaws in chaotic-DNA ciphers, exposing their vulnerability to chosen-plaintext attacks. Chen Y. et al.19 examined the security of medical image encryption, identifying issues related to scrambling and diffusion techniques. Feng W. et al.20 investigated a Feistel-based DNA encryption scheme and proposed improvements to enhance its resilience against cryptanalysis techniques. These studies emphasize that many existing encryption structures lack proper ciphertext or plaintext feedback mechanisms, making them vulnerable to known-plaintext and chosen-plaintext attacks. To address these concerns, our proposed encryption scheme integrates hash based key generation and ciphertext feedback method, ensuring resistance against such attacks while maintaining high security and efficiency.

Significant progress has been made recently in cryptography based on DNA encoding and chaos theory. In order to create a different chaotic image encryption process, Alrubaie A. et al.21 used DNA encoding techniques in conjunction with Arnold transformations to create a 2D distinct chaotic method with constant Lyapunov exponents. A novel nonlinear chaotic system with hyperchaotic characteristics was also presented by them. By putting out a novel data encryption technique that combines Henon chaotic map with DNA. Liu C22. solved the shortcomings of the current DNA encryption algorithms. This technique showed good security and encryption performance. Jiang G. et al.23 presented a novel hash function-based picture cryptography technique that combines DNA and chaotic operations. This approach has limits when it comes to thwarting noise attacks, but it effectively withstands statistical and differential attacks. Ravichandran D. et al.24 efficiently encrypted medical images utilizing DNA technology and chaos theory. Sun S. et al.25 have presented an innovative approach to image encryption that combines DNA encoding with additional image scrambling and deconstruction techniques. However, this approach requires security enhancements because it has a limited key space and finds it difficult to successfully thwart different types of assaults. Combining DNA encoding approaches can increase the complication and safety of encryption because single chaotic systems frequently struggle with safety and attack conflict in image encryption.

Despite rapid advancement in digital technology and the internet, many developments remained constrained by the limitation of their times: (1) Current encryption algorithm structure is either illogical or very basic. In the absence of ciphertext feedback or plaintext association, the technique is susceptible to chosen plaintext or known-plaintext attacks. (2) Full encryption or global encryption encrypts a large amount of redundant data, wasting communication capacity and performance. (3) Low-dimensional chaotic systems have limited complexity and smaller key space, making them more susceptible to brute force attacks.

Following are the primary innovations and contributions of this paper.

-

1.

Encrypting the complete image is the main goal of the majority of image encryption systems now in use. Researchers frequently encrypt the entire image when analyzing facial images, failing to take redundant information protection into account. Local encryption of facial images is required to advance the safety and usefulness of encryption systems.

-

2.

DNA encoding offers images a higher level of security than pixel-level encryption. The proposed scheme uses a more sophisticated and effective DNA-based encryption mechanism. To reach a higher level of encryption, it re-encodes the image’s pixels using DNA sequences. Furthermore, this algorithm uses a number of DNA manipulation principles to rise the complication and strength of the encryption and decryption procedures. Results from experiments show that this technique successfully improves image encryption security.

-

3.

Current encryption schemes make use of single operation rule and easily cracked encoding techniques. This face encryption scheme, in contrast to earlier encryption schemes, includes a number of encryption techniques, such as Color permutation, Scrambling, DNA encryption, bit-level confusion and irregular diffusion. This Multi-Dimensional cryptic transformation strengthens the face encryption scheme’s security and resilience, increasing its resistance to attacks and guaranteeing the privacy of face images.

-

4.

To achieve a balance between computational efficiency and encryption robustness, this paper utilizes a 4D hyperchaotic Chen map instead of higher-dimensional or lower-dimensional chaotic systems. This choice ensures improved precision in chaotic sequence generation while significantly reducing computational time, making the proposed face encryption scheme both time-efficient and precise.

-

5.

A lot of the encryption algorithm structures in use today are irrational. These are at risk to attacks without plain image or cipher image feedback. Using a cipher image feedback mechanism, the proposed face encryption scheme updates the encoding key in response to data. The safety and resilience against attacks, are improved by this feedback mechanism. The hash based key generation and cipher image feedback mechanism guarantees that the proposed face encryption scheme is resistant to both chosen plaintext and ciphertext attacks.

Preliminaries

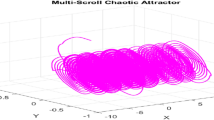

This section delivers a summary of the key concepts and methodologies used in our proposed face encryption scheme. It begins with an introduction to the basic principles of cryptography. Following this, we discuss the chaotic systems employed in our work, particularly focusing on the 4D hyperchaotic Chen system. We introduce the system’s partial chaotic attractors in both the plane and space, and illustrate these concepts with figures to highlight their relevance in encryption.

DNA technology

In 1994, DNA cryptography was proposed by Adleman L. et al.26. Early studies concentrated on creating encryption methods using the chemical and physical characteristics of DNA molecules. DNA is seen as a potential cryptography tool due to its complicated biological properties and extremely dependable information storing capability. Researchers are now investigating DNA as a novel encryption technique in cryptography due to the ongoing advancements in DNA technology27.

‘Adenine (A)’, ‘thymine (T)’, ‘cytosine (C)’ and ‘guanine (G)’ are four different nucleotides found in DNA sequences. A compliments with T, and G compliments with C. Likewise, 00 and 01 are compliments of 11 and 10 respectively in binary integers. We have 24 alternative encryption rules because binary numbers and nucleotides can be used interchangeably. However, as Table 1 illustrates, only eight of these rules meet the complimentary condition.

Take an image pixel having value 189, for instance. The output is “AGGT” if we substitute the binary sequence “10111101” for this value and encode it using Table 1’s encoding rule number 3. An original pixel value can be precisely recovered by using the similar coding algorithm for decoding. Similarly, pixel value 199 is encoded as “TAGT” when encoding rule number 6 is applied, the original value can still be recovered using the same technique. Nevertheless, the binary sequence “11001011,” which doesn’t connect to actual value, is produced when encryption rule number 7 is applied. This illustrates how using different rules to encode and decode a single pixel can provide different outcomes. The six fundamental operations in DNA computation are addition, subtraction, XoR, Addition Compliment, Subtraction Complement, and XNoR. The specific DNA operations using rule 3 from Table 1 are displayed in Table 2.

The chaotic system

In this paper, as a Chaotic system we have used hyperchoatic Chen system28. This system is designed to generate more complex and unpredictable dynamical behavior. It has two or more positive Lyapunov exponents, indicating greater sensitivity to initial conditions and a higher degree of randomness compared to standard chaotic systems. The hyperchaotic Chen system is described by four first-order nonlinear differential equations given in Eq. (1):

In the above system, \(\:d/dt\) represents the derivative of the variables \(\:x,y,z,q\) w.r.t time t. The system is in Hyperchaotic state when \(\:\alpha\:\:=\:35,\:\:\beta\:\:=\:3,\:\:\gamma\:\:=\:12,\:\:r=7\:and\:s\:=0.55\).The chaotic dynamics of the hyperchaotic Chen system can be further analyzed through bifurcation diagrams and Lyapunov exponents plots which provide insight into stability of chaotic system29. We have illustrated the system’s dynamics using partial chaotic attractors, as displayed in Fig. 1.

Face encryption scheme

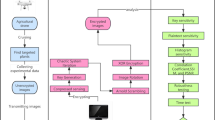

The Face Encryption Scheme begins with face detection, using an edge recognition method to isolate the face. Then the selected matrix is encrypted by calculating eigenvalues and applying SHA-256. These hashes initialize a 4D hyperchaotic Chen system for generation of keys. The chaotic sequences taken from the Chen system are employed for color permutation, zigzag scrambling, DNA encoding, ciphertext feedback mechanisms, irregular diffusion and bit-level confusion. In this way, Multi-dimensional encryption procedure is carried out using a novel ciphertext feedback technique, which raises the complication of the algorithm and fortifies its defenses against attacks.

Face detection and encryption workflow

The face detection process begins by applying edge recognition method30 to get the face containing delicate information. The image is first smoothed using linear filter to lessen sufficient details and then the binary image is obtained. A morphological–based face detection method is utilized to refine facial features. Morphological boundary extraction is used to isolate the face, effectively handling smaller connected regions caused by darker skin tones to minimize detection errors. A closure process, using upright extended shaping elements, removes interloping from hair, clothing, and other distractions while preserving the facial region. Next, lateral erosion segments large body parts and eliminates background noise, refining the detected area. Finally, the largest connected domain matching facial feature criteria is selected. The mathematics behind the face detection scheme is given in31. Figure 2 represents the steps of the face detection.

The final facial image then moves to the encryption stages, which include Color permutation, zigzag scanning, DNA encoding, irregular diffusion and confusion, resulting in fully encrypted image. The workflow diagram of the encryption process is depicted in Figure 3.

Encryption process

To initialize the encryption process, an image \(\:I\) of dimensions \(\:512\times\:512\times\:3\) is chosen. The eigenvalues of face image are calculated, and SHA-256 data hash is applied to produce scanning values \(\:H\left(\phi\:\right),\) where \(\:\phi\:\in\:[1,\:32].\) These values are used to generate key parameters as shown in Eq. (2).

Here, \(\:\theta\:\) acts as the key parameter, while \(\:x\left(0\right),\:y\left(0\right)\:,\:z\left(0\right)\:and\:q\left(0\right)\) are used as preliminary values for the chaotic system. These parameters are deputize for the 4D Hyperchaotic Chen system to produce four sequences\(\:{\:Q}_{1},{Q}_{2}\),\(\:{Q}_{3}\) and\(\:\:{Q}_{4}\). To ensure the sequences meet the algorithm’s requirements, the Eq. (3) are applied.

where \(\:floor\left(.\right)\) is the downward function and \(\:mod\left(.\right)\) is the modular action. \(\:{Q}_{RGB}\) and \(\:{Q}_{bit}\) are disordered sequences that serve for Color permutation and confusion, respectively.

Encryption stage 1: color permutation

During the encryption process, the orignal image I is decomposed into its RGB channels and transformed into 1D vectors \(\:{I}_{R}\),\(\:\:{I}_{G}\) and \(\:{I}_{B}\), each of size M×N. The permutation of these RGB channels is guided by the chaotic sequence \(\:{Q}_{RGB}\left(n\right)\) as depicted in Table 3. We get image \(\:{I}_{1}\) after Color permutation.

Encryption stage 2: interleaved scrambling process of zigzag

Zigzag Scrambling initializes a 3D matrix \(\:{I}_{1}\) of size \(\:M\times\:N\) to store the scrambled RGB image. Each color channel (red, green, blue) is processed separately. The image matrix is conceptually divided into two halves: the upper half and the lower half. Zigzag scanning is applied to fill upper half: Odd rows are scanned from left to right, while even rows are scanned from right to left. In reverse zigzag scanning for filling the lower half, the pattern is inverted: odd rows are scanned from right to left, and even rows are scanned from left to right. A new array is created by interleaving the values of upper and lower half with odd indices taking values from upper half and even indices from lower half. The interleaved array is reshaped into a 2D matrix with dimensions to reconstruct the scrambled channel. The scrambled channel is stored in the corresponding layer of the output matrix\(\:\:{I}_{2}\) that is used for further encryption, as shown in Fig. 4.

Encryption stage 3: DNA encoding

Before initiating DNA encryption, we generated of the chaotic sequence \(\:{Q}_{k},\:{Q}_{E}\:and\:{Q}_{D}\:\)given in Eq. (4).

First, the sequence \(\:{Q}_{k}\) is utilized to reconstruct the matrix as a key K. Subsequently, DNA encoding is carried out using the sequence \(\:{Q}_{E.}\)The key matrix and cipher image are expanded to binary form, and DNA encoding is applied to resulting binary sequence using Table 1. The encryption rules are altered after 8 bits to increase complication and system safety. The DNA coding is defined in Eq. (5).

At the completion of this step, a matrix with height M and width \(\:4\times\:\text{N}\) is obtained.

Encryption stage 4: ciphertext feedback mechanism

To strengthen the encryption technique ability to resist attacks, a ciphertext feedback mechanism is employed in the DNA domain. This increases the involvedness between original image, keys, and cipher image. The DNA dynamic operation is depicted in Eq. (6).

Here, p = 2\(\:\times\:\text{M}\),\(\:\:q=14\times\:\text{N}\), \(\:{I}_{d}\) and \(I^{\prime}_{d}\) are intermediate cipher images, K is the encoded chaotic matrix, and the operations and sub(.), XoR(.) and add(.) represent DNA subtraction, XOR and addition operation respectively. The process utilizes the DNA matrix’s previous position to encrypt the next position, achieving chain encryption. The final ciphertext is denoted as \(\:{I}_{3}\).

Encryption stage 5: DNA decoding

The DNA decoding procedure mirrors the encoding but uses the sequence \(\:{Q}_{D}\), distinguishing it as an additional encryption transformation rather than a simple reverse process. The DNA decoding process is defined in Eq. (7).

Here, \(I^{\prime}_{3}\) represents the image obtained after the process of DNA decoding.

Encryption stage 6: irregular diffusion

To enhance the diffusion feature of encryption scheme, a non-sequential pixel processing method is implemented. This avoids fixed processing orders that might reduce encryption performance. Pixels are influenced by others from the same or different color planes based on a chaotic sequence. The encryption operation is given in Eq. (8).

Here \(\:mod(.)\) represents the modular function, \(I^{\prime}_{3}\) is the image, A is the Chaotic matrix obtained from the chaos sequence \(\:{Q}_{4}\) and F represents the number of pixel value in every colored image\(I^{\prime}_{3}\). The ciphertext \(\:{I}_{4}\) is the final output.

Encryption stage 7: bit-level confusion

To further advance encryption enactment, a bit-level confusion mechanism is applied. The chaos sequence \(\:{Q}_{bit}\) is employed to reconstruct the key matrix\(\:{\:K}_{h}\). The image \(\:{I}_{4}\) is XoRed with the key matrix \(\:{K}_{h}\) and then shifted to the right by\(\:\:j-bits\), where \(\:j\in\:\left[\text{1,999}\right]\). The procedure is given in Eq. (9).

The image \(\:{I}_{5}\) represents the final encrypted result, completing the encryption process

Decryption process

To begin the decryption process, the required encryption keys are obtained. Specifically, the encryption keys: \(\:{Q}_{1},{Q}_{2},{Q}_{3}\:and\:{Q}_{4}\) which are generated using the SHA-256 hashes of the plain images, are securely shared between the sender and receiver.

Decryption stage 1: reverse bit-level confusion

Bit-level confusion is reversed as follows:

-

1.

Perform a bit-level left shift by s-bits on the final encrypted image \(\:{I}_{5}\), ensuring all bits are correctly realigned.

-

2.

XOR the shifted result with the reconstructed key matrix \(\:{K}_{h}\), generated using the chaotic sequence \(\:{Q}_{bit}\), to obtain \(\:{I}_{4}\).

Decryption stage 2: reverse irregular diffusion

Irregular diffusion process is reversed using the chaotic sequence \(\:{Q}_{4}\) and the chaos matrix A. For each pixel in \(\:{I}_{4}\text{},\:\)calculate the inverse operation of Eq. (8), using the modular relationship and previously processed pixels to reconstruct \(I^{\prime}_{3}\).

Decryption stage 3: reverse DNA decoding

The DNA decoding step is reversed using the sequence \(\:{Q}_{D}\):

-

1.

The encoded image \(I^{\prime}_{3}\) is processed in blocks of size 12×H×W, decoding each block sequentially based on the rules defined in Eq. (7).

-

2.

Reconstruct the original DNA-encoded image \(\:{I}_{3}\).

Decryption stage 4: reverse ciphertext feedback mechanism

To reverse the feedback mechanism:

-

1.

Perform the DNA operations (subtraction, XoR, addition) in reverse order, using the chaotic matrix K and the intermediate ciphertexts \(\:{I}_{d}\:\)and \(I^{\prime}_{d}\) following Eq. (6).

-

2.

Restore the DNA-encoded matrix \(I^{\prime}_{2}\).

Decryption stage 5: reverse DNA encoding

The DNA dynamic encoding is reversed using the sequence \(\:{Q}_{E}\):

-

1.

Process the DNA matrix \(I^{\prime}_{2}\)and key matrix K′ using the reverse of the encoding rules defined in Eq. (5).

-

2.

Reconstruct the original intermediate image \(\:{I}_{2}\).

Decryption stage 6: reverse zigzag scrambling

The scrambled 3D matrix \(\:{I}_{2}\) is processed to undo the zigzag scanning:

-

1.

Separate the interleaved array into upper and lower halves. Odd indices of interleaved array are mapped to the upper half, and even indices to the lower half.

-

2.

Apply reverse zigzag scanning to reconstruct the red, green, and blue channels of \(\:{I}_{1}\).

Decryption stage 7: reverse color permutation

Using the chaotic sequence \(\:{Q}_{RGB(}\left(i\right)\), the RGB permutation is reversed based on the rules in Table 3:

-

1.

Assign each channel in \(\:{I}_{1}\) to its original position (R, G, B).

-

2.

Combine the channels to reconstruct the original image \(\:I\).

This completes the decryption process, recovering the original plain image. Figure 5 illustrates the workflow diagram of the decryption process.

Simulation results and security analysis

This section incorporates several widely used performance evaluation metrics from existing research. We tested our proposed face encryption scheme using facial images of various dimensions to assess its performance and robustness. The following subsections discuss a diverse range of testing metrics.

Experimental configurations

The proposed face encryption scheme was experienced using a PC running MATLAB R2023a. The system is fitted out with an Intel i5-6300U processor and 16 GB RAM. The images used in the paper were sourced from the Kaggle Human Face Detection database32. The dataset was retrieved on January 6, 2025 from https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sbaghbidi/human-faces-object-detection.

Entropy

Entropy is a critical metric for evaluating the uncertainty and randomness of grayscale values in images, making it essential in assessing image encryption algorithms. Mathematically, information entropy is expressed in Eq. (10)

where \(\:X\) represents the entire amount of variables, and \(\:p\left({m}_{i}\right)\) denotes the probability of each variable. The ideal entropy value for a perfectly encrypted image is 8 bits33,34,35. This designates that the pixel distribution is uniform, meaning the encryption has maximized randomness and minimized any patterns that could be exploited for cryptanalysis. In this study, the information entropy of original images and its cipher were calculated and compared. The experimental results shown in Table 4, reveals that the proposed face encryption scheme attains an average entropy of 7.9985. This point to a high degree of unpredictability in the cipher images, enhancing resistance to statistical analysis.

Image quality assessment

Mean square error (MSE)

MSE is a statistical measure used to estimate the variance between two images, typically an original image and its cipher or reconstructed form. It calculates the average squared difference of pixel intensities and is defined in Eq. (11).

Where, \(\:P\:and\:Q\) represents the height and width of the image, respectively and \(\:U\left(r,s\right)\:and\:V\left(r,s\right)\) represent the pixel at location \(\:\left(r,s\right)\:\)in the plain and its cipher image, respectively.

Peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR)

PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) is derived from the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and measures the worth of an image, particularly after encryption. A higher PSNR indicates better quality. It is calculated using Eq. (12).

where Q is the maximum possible pixel value (for an 8-bit image, \(\:Q=255\)). Smaller MSE values correspond to larger PSNR values, implying better quality. In effective encryption, the PSNR of cipher image is less than 10 dB, indicating significant deviation from the plain image.

Structural similarity index (SSIM)

Structural Similarity Index evaluates the perceptual similarity between two images by assessing their luminance, contrast, and structural content. It is defined using Eq. (13).

Where \(\:{\lambda\:}_{U}\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{V}\) shows the average values of images U and V respectively. L expresses the dynamic range of pixels. SSIM value range from − 1 to 1, where 1 point to identical images, and values close to 0 suggest no similarity. For effective encryption, the SSIM value between the plain and its cipher image should be close to 0, indicating a lack of perceptual similarity.

The proposed face encryption scheme was tested for MSE, PSNR, and SSIM values using various images. The results in Table 4 shows that MSE values are high, indicating significant changes in pixel intensity, PSNR values are less than 10 dB, confirming the effectiveness of encryption and SSIM values are near 0, indicating minimal structural similarity between original and encrypted images. These metrics validate strength of the proposed method against statistical and visual analysis assaults, ensuring secure encryption.

Histogram analysis

To ensure adaptability across various applications, image encryption algorithms must effectively transform different images into cipher images. These algorithms should guarantee that the actual image could only be accurately restored with right encryption key, rendering it impossible to extract meaningful information without it. Histogram analysis offers acute visions into the distribution of pixels inside an image. The encryption algorithm was tested using images with diverse color profiles. Figure 6 showcases the histograms of plain and its cipher images. The even pixel distribution observed in all the three channels (Red, Green and Blue) of the cipher image underscores the system’s capability to transform regular images into secure, high quality cipher images.

In the original image, neighboring pixels exhibit minimal differences and maintain high correlations in vertical, horizontal and diagonal directions. A robust image encryption procedure effectively disrupts this correlation, turning it nearly unbearable to decode the encoded image by attacks. The correlation between adjoining pixels is defined in Eq. (14).

Here, \(\:{r}_{p}\) and \(\:{s}_{p}\) represent the \(\:pth\) pair of adjoining pixels in horizontal, vertical and diagonal directions, \(\:Q\) is the total number of pixel pairs, \(\:cov\left(r,s\right)\) is the covariance, \(\:F\left(r\right)\) and \(\:F\left(s\right)\) are the Mean Square Error of \(\:r\) and \(\:s\) respectively, \(\:G\left(r\right)\) and \(\:G\left(s\right)\) shows the estimated values of r and s respectively and \(\:{s}_{mn}\) is the correlation of \(\:r\:and\:s.\)

A primary objective of image encryption is to break pixel correlations, thereby preventing decryption based on statistical analysis. Correlation measurements of original and encoded images for horizontal, vertical, and diagonal orientations were computed, and sprinkle plots were generated as depicted in Figs. 7 and 8. The results, precised in Table 5, demonstrate that the proposed encryption algorithm significantly reduces pixel correlations. The ciphertext exhibits almost no discernible correlation, highlighting the algorithm’s strong security capabilities.

Differential attack analysis

The Number of Pixel Change Rate (NPCR) and Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI) are commonly used metrics to assess the image data encryption approaches, especially their opposition to differential attacks. These metrics measure the algorithm’s permutation and diffusion properties, which are essential for ensuring robust encryption. The mathematical form of NPCR and UACI is given in Eq. (15).

Here, \(\:P\times\:Q\) symbolizes the dimensions of the image, and \(\:{u}_{1}\) and \(\:{u}_{2}\) are the pixel values of the cipher images earlier and later a single pixel in the plain image is transformed. \(\:F\) is defined in Eq. (16).

The ideal NPCR and UACI values are 99.6094070% and 33.4635070% respectively36,37,38. In this study, we tested the values of NPCR and UACI of different images, as detailed in Table 6. The investigational outcomes demonstrate that the encryption process achieves values very near to the theoretic benchmarks, confirming its effectiveness in repelling differential attacks.

Key space analysis

A key space discusses the complete set of potential keys in encryption procedure, with its size being determined by the length and complexity of the encryption key. A larger key space strengthens the cryptosystem by making it more resilient to brute force attacks. When the key range surpasses\(\:\:{2}^{100}\), the likelihood of successful brute force attacks is significantly decreased. In this paper, the face encryption scheme employs SHA-256 and 4D hyperchaotic Chen system, to generate four 256 bit keys. This approach expands the key range to\(\:{\:2}^{1024}\), vastly surpassing \(\:{2}^{100}\) and enhancing security.

A larger key space requires significantly more time for breakdown, ensuring the strength of the data encryption approach in contradiction of brute force attacks. The outcomes confirm that the key space generated by this scheme is sufficiently large to provide strong security. A comparison of key space sizes with other encoding techniques is presented in Table 7.

Key sensitivity test

Key sensitivity inspects how minor alterations in the key affects the subsequent ciphertext43. In this analysis, the original image was encrypted using the right keys and slightly altered keys:\(\:\:{K}_{1}+{10}^{-13}\), \(\:{K}_{2}+{10}^{-14}\), \(\:{K}_{3}+{10}^{-15}\)and \(\:{K}_{4}+{10}^{-16}\). The differences of resultant cipher images were evaluated by computing the UACI and NPCR values defined in Eq. (15). The findings presented in Table 8, demonstrate that even minimal modifications to the key produce considerably different cipher images. The NPCR and UACI values for these tests are nearby to 99.6094070% and 33.4635070%, respectively that are the ideal values, confirming the algorithm’s resilient key sensitivity and its opposition to differential attacks.

Analysis of noise and data loss

We assessed the robustness of the face encryption scheme by conducting tests against both noise and data loss. In the case of noise attacks, the cipher image was subjected to salt and pepper noise at varying intensity levels, including 5%, 10%, and 25%. The impact of noise on the decrypted images was analyzed, demonstrating the algorithm’s resilience in maintaining image integrity despite increasing noise levels. The results, as depicted in Fig. 9 confirms that the proposed face encryption scheme productively mitigates the effects of noise, ensuring reliable image recovery.

For data loss analysis, we implemented a cropping attack test to assess the algorithm’s ability to reconstruct an image with missing portions. Different levels of intentional cropping were applied to the encrypted image, removing sections equivalent to 25%, 50% and 80%. The cropped cipher images were then reconstructed, and the results, displayed in Figure 10 indicates that despite partial data loss, the decrypted images retained significant visual information. This highlights the performance of the face encryption scheme in repelling data loss and confirming image recovery even under severe cropping conditions.

Time complexity

In any encryption process, the total time taken by an algorithm to complete its operations is referred to as computation time. This time is mainly determined by the number of arithmetic operations the algorithm performs. To enhance efficiency and reduce resource consumption, it is essential to minimize these operations. An increase in the number of operations can lead to higher energy usage and longer execution times, ultimately affecting the algorithm’s overall performance. To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed scheme, a comparison with other existing algorithms has been carried out using a 512 × 512 image, as illustrated in Table 9.

Summary and comparison of the proposed face encryption scheme

In this section, we summarize the results of proposed face encryption scheme by presenting the average values that we obtained from performance evaluation metrics. We tested our proposed face encryption scheme using facial images of various dimensions. Table 10 presents the average results for different performance evaluation metrics. We tested our scheme using common benchmark image of Mandrill, to verify the stability and adaptability of our encryption technique. In image processing and cryptography, the image of Mandrill is widely used for evaluation. Figure 11 demonstrates the performance of our scheme on Mandrill image, showcasing its applicability to other commonly used research images. Table 11 presents a comparison of the Mandrill image with other related works in the literature.

Conclusion and future work

To address the critical issue of data safety for drone captured facial images, this paper recommends a face encryption scheme grounded on a 4D hyperchaotic Chen system, SHA-256 hashing, color permutation, zigzag scanning, DNA coding, confusion and diffusion. Unlike traditional full-image encryption, the proposed approach selectively encrypts the face region containing sensitive information. This significantly enhances the efficiency of encryption scheme while maintaining high security.

The use of plaintext or intermediate ciphertext association in chaotic sequence generation enhances resistance against chosen-plaintext attacks. The incorporation of the 4D hyperchaotic Chen system and SHA-256 hashing ensures robust key generation, significantly escalating the key space and strengthening the encryption system’s security. Experimental results and theoretical analysis demonstrate the proposed algorithm’s superiority in key performance indicators such as histogram uniformity, correlation reduction, high information entropy and resistance to various attacks. The large key space and the ability of proposed face encryption scheme to effectively resist brute-force and statistical attacks underscore its robustness and reliability.

Although the proposed face encryption scheme leverages the 4D hyperchaotic Chen system for strong security, one limitation is the lack of evaluation against machine learning-based cryptanalysis attacks and quantum computing attacks, which could pose a potential security risk in the future.

Future research can explore other chaotic models that offer better efficiency or adaptability to different UAV images. Efforts can also focus on optimizing the algorithm for large-scale image processing while ensuring compatibility with next-generation UAV imaging and cloud-based storage platforms. Additionally, enhancing resistance to quantum computing attacks and integrating quantum-resistant cryptographic primitives will be crucial. The proposed face encryption scheme will also be tested against advanced cryptanalytic models such as those used by Jiang D. et al.51, which leverage deep learning to reconstruct original faces from encrypted data. Moreover, the current system focuses primarily on facial data, and future work could explore the encryption of other sensitive data types in UAV systems.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

Wen, H., Xie, Z., Wu, Z., Lin, Y. & Feng, W. Exploring the future application of uavs: face image privacy protection scheme based on chaos and DNA cryptography. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inform. Sci. 36, 101871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101871 (2024).

Singh, J., Lata, K. & Ashraf, J. Image encryption & decryption with symmetric key cryptography using MATLAB. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 5 (1), 448–454 http://inpressco.com/category/ijcet (2015).

Kumar, R. & Mathew, J. A mathematical interpretation of images and image encryption. Int. J. Math. Trends Technol. 66 (6), 190–194. https://doi.org/10.14445/22315373/IJMTT-V66I6P518 (2020).

Yin, H. L. et al. Experimental quantum secure network with digital signatures and encryption. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10 (4), nwac228. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwac228 (2023).

Youssef, M. et al. Enhancing satellite image security through multiple image encryption via hyperchaos, SVD, RC5, and dynamic S-box generation. IEEE Access. 12, 123921–123945. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3454512 (2024).

Pareek, N. K., Patidar, V. & Sud, K. K. Image encryption using chaotic logistic map. Image Vis. Comput. 24 (9), 926–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2006.02.021 (2006).

Patidar, V., Pareek, N. K. & Sud, K. K. A new substitution–diffusion-based image cipher using chaotic standard and logistic maps. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 14 (7), 3056–3075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2008.11.005 (2009).

Wang, X., Teng, L. & Qin, X. A novel colour image encryption algorithm based on chaos. Sig. Process. 92 (4), 1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sigpro.2011.10.023 (2012).

Cang, S., Qi, G. & Chen, Z. A four-wing hyper-chaotic attractor and transient chaos generated from a new 4-D quadratic autonomous system. Nonlinear Dyn. 59, 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-009-9558-0 (2010).

El-Damak, D. et al. Fibonacci Q-matrix, hyperchaos, and Galois field (2⁸) for augmented medical image encryption. IEEE Access. 12, 102718–102744. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3433499 (2024).

Feng, W. et al. Exploiting robust quadratic polynomial hyperchaotic map and pixel fusion strategy for efficient image encryption. Expert Syst. Appl. 246, 123190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123190 (2024).

Feng, W. et al. Exploiting newly designed fractional-order 3D Lorenz chaotic system and 2D discrete polynomial hyper-chaotic map for high-performance multi-image encryption. Fractal Fract. 7 (12), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract7120887 (2023).

Qian, K. et al. A robust memristor-enhanced polynomial hyper-chaotic map and its multi-channel image encryption application. Micromachines 14 (11), 2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14112090 (2023).

Gao, S. et al. EFR-CSTP: encryption for face recognition based on the chaos and semi-tensor product theory. Inf. Sci. 621, 766–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2022.11.121 (2023).

Alexan, W. et al. Secure communication of military reconnaissance images over UAV-assisted relay networks. IEEE Access. 12, 3407838. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3407838 (2024).

Hadi, H. J., Cao, Y., Nisa, K. U., Jamil, A. M. & Ni, Q. A comprehensive survey on security, privacy issues and emerging defence technologies for UAVs. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 213, 103607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2023.103607 (2023).

Wen, H. & Lin, Y. Cryptanalysis of an image encryption algorithm using quantum chaotic map and DNA coding. Expert Syst. App. 237 (Part B), 121514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121514 (2024).

Wen, H. & Lin, Y. Cryptanalyzing an image cipher using multiple chaos and DNA operations. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inform. Sci. 35 (7), 101612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101612 (2023).

Chen, Y., Tang, C. & Ye, R. Cryptanalysis and improvement of medical image encryption using high-speed scrambling and pixel adaptive diffusion. Sig. Process. 167, 107286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sigpro.2019.107286 (2020).

Feng, W., Qin, Z., Zhang, J. & Ahmad, M. Cryptanalysis and improvement of the image encryption scheme based on feistel network and dynamic DNA encoding. IEEE Access. 9, 145459–145470. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.312357 (2021).

Alrubaie, A. H., Khodher, M. A. A. & Abdulameer, A. T. Image encryption based on 2DNA encoding and chaotic 2D logistic map. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 70 (60). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-023-00228-2 (2023).

Liu, C. C. Chaotic information encryption algorithm based on DNA strand displacement reaction. J. Changchun Normal Univ. 42 (2), 65–71 (2023).

Jiang, G., Guo, X. & Yang, C. Simulation of image encryption algorithm combining chaos and DNA operations. Comput. Simul. 38 (5), 176–180 (2021).

Ravichandran, D. et al. An efficient medical image encryption using hybrid DNA computing and chaos in transform domain. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 59, 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-021-02328-8 (2021).

Sun, S. A novel hyperchaotic image encryption scheme based on DNA encoding, pixel-level scrambling, and bit-level scrambling. IEEE Photon. J. 10 (2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2018.2817550 (2018).

Adleman, L. M. Molecular computation of solutions to combinatorial problems. Science 266 (5187), 1021–1024 https://www.jstor.org/stable/2885489 (1994).

Wen, H. et al. Secure DNA-coding image optical communication using non-degenerate Hyperchaos and dynamic secret-key. Mathematics 10 (17), 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10173180 (2022).

Li, R., Liu, T. & Yin, J. An encryption algorithm for color images based on an improved dual-chaotic system combined with DNA encoding. Sci. Rep. 14, 20733. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-20733-2 (2024).

Alexan, W., El-Damak, D. & Gabr, M. Image encryption based on Fourier-DNA coding for hyperchaotic Chen system, Chen-based binary quantization S-box, and variable-base modulo operation. IEEE Access. 12, 21092–21113. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3363018 (2024).

Yang, G. & Huang, T. S. Human face detection in a complex background. Pattern Recogn. 27 (1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-3203(94)90017-5 (1994).

Arulkumar, V., Prakash, S. J., Subramanian, E. K. & Thangadurai, N. An intelligent face detection by corner detection using special morphological masking system and fast algorithm. 2021 2nd Int. Conf. Smart Electron. Communication (ICOSEC). 1556, 1561. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOSEC51865.2021.9591857 (2021).

Human Faces (Object Detection). Kaggle. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sbaghbidi/human-faces-object-detection (Accessed 06 Jan 2025) (2025).

Ravichandran, D., Jebarani, W. S. L. & Amirtharajan, R. An efficient medical data encryption scheme using selective shuffling and inter-intra pixel diffusion IoT-enabled secure E-healthcare framework. Sci. Rep. 15, 4143. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85539-5 (2025).

Lakshmi, C. et al. Reconfigurable security solution based on Hopfield neural network for e-healthcare applications. Sci. Rep. 15, 5628. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88561-9 (2025).

Chidambaram, N., Thenmozhi, K., Raj, P. & Amirtharajan, R. DNA-chaos governed cryptosystem for cloud-based medical image repository. Cluster Comput. 27, 4127–4144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-024-04391-w (2024).

Liu, H., Liu, J. & Ma, C. Constructing dynamic strong S-Box using 3D chaotic map and application to image encryption. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 23899–23914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12069-x (2023).

Banu, A. S. & Amirtharajan, R. A robust medical image encryption in dual domain: Chaos-DNA-IWT combined approach. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 58, 1445–1458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-020-02178-w (2020).

Ravichandran, D., Praveenkumar, P., Rayappan, J. B. B. & Amirtharajan, R. DNA chaos blend to secure medical privacy. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 16 (8), 1430–1438. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNB.2017.2780881 (2017).

Gabr, M. et al. Application of DNA coding, the Lorenz differential equations, and a variation of the logistic map in a multi-stage cryptosystem. Symmetry 14 (12), 2559. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14122559 (2022).

Alexan, W., Alexan, N. & Gabr, M. Multiple-layer image encryption utilizing fractional-order Chen hyperchaotic map and cryptographically secure PRNGs. Fractal Fract. 7 (4), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract7040287 (2023).

Elkandoz, M. T. & Alexan, W. Image encryption based on a combination of multiple chaotic maps. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81, 25497–25518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12595-8 (2022).

Iqbal, N. et al. On the image encryption algorithm based on the chaotic system, DNA encoding, and castle. IEEE Access. 9, 118253–118270. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3106028 (2021).

Liu, H., Kadir, A. & Niu, Y. Chaos-based color image block encryption scheme using S-box. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 68 (7), 676–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2014.02.002 (2014).

Inam, S., Kanwal, S., Firdous, R. & Hajjej, F. Blockchain-based medical image encryption using arnold’s Cat map in a cloud environment. Sci. Rep. 14, 5678. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-42679-6 (2024).

Neela, K. L. & Kavitha, V. Blockchain-based chaotic deep GAN encryption scheme for Securing medical images in a cloud environment. Appl. Intell. 53, 4733–4747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-022-03503-2 (2023).

Afzal, I., Parah, S. A. & Song, O. Y. Secure patient data transmission on resource constrained platform. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 15001–15026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-020-08909-9 (2024).

Alexan, W., ElBeltagy, M. & Aboshousha, A. RGB image encryption through cellular automata, S-box, and the Lorenz system. Symmetry 14 (3), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14030443 (2022).

Kanwal, S. et al. A robust approach to satellite image encryption using chaotic map and circulant matrices. Eng. Rep. 6 (12), e13010 https://doi.org/10.1002/eng2.13010 (2024).

Dridi, M., Hajjaji, M. A., Bouallegue, B. & Mtibaa, A. Cryptography of medical images based on a combination between chaotic and neural network. IET Image Proc. 10 (11), 830–839. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-ipr.2015.1152 (2016).

Wang, J., Li, J., Di, X., Zhou, J. & Man, Z. Image encryption algorithm based on bit-level permutation and dynamic overlap diffusion. IEEE Access 8, 160004–160024. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3019671 (2020).

Jiang, D. et al. DDCM: cracking anonymized facial images using denoising diffusion cryptanalytic model. IEEE Trans. Consumer Electron. Adv. Online Public. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2024.3370601

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R125), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1. Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Supervision: Saba Inam 2. Formal Analysis, Visualization, Validation: Shamsa Kanwal 3. Experimental Results, writing original Draft: Eaman Amin 4. Validation, Review and editing draft: Omar Cheikhrouhou and Monia Hamdi.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Inam, S., Kanwal, S., Amin, E. et al. Securing face images in UAV networks using chaos and DNA cryptography approach. Sci Rep 15, 26011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11499-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11499-5