Abstract

Proper synchronization between transmitter and receiver ports in time-domain measurements is of great importance. This study presents a novel synchronization method that can be applied to data acquired from dual single-shot samplers in real time, diverging from the conventional approach that utilizes a single-shot sampler with an external trigger to synchronize the input signal. Following synchronization algorithm, its effectiveness is validated through experimental testing using a time-dependent, narrow-band transient radar signal. The experiments on a 5-cm thick polyvinylchloride (PVC) sample demonstrated the reliability of the proposed method. The transient radar signal utilized in the experiments had a carrier frequency of approximately 10 GHz, while data acquisition was carried out with an independent external trigger using only a 2 MHz sinusoidal signal. Applying the synchronization technique to the measurement results yielded a complex relative dielectric permittivity of (2.55 ± 0.02) – (0.23 ± 0.01)j. Using this value to calculate the speed of light in the PVC sample, the thickness was determined to be 5.29 ± 0.13 cm. Further refinement of the effective angle enhanced measurement accuracy, ultimately yielding a thickness of 4.83 ± 0.11 cm and reducing the relative error from 5.8 to 3.4%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

General background information

Synchronization between transmitter and receiver elements in time-domain measurement systems is crucial to ensure an accurate representation of received signals. By capturing signals at the appropriate time, preventing phase drift, maintaining a precise trigger scheme, coping with signal jitter, and avoiding frequency mismatch, synchronization minimizes phase noise and signal distortions. These challenges become significantly more severe at higher frequencies, such as in the millimeter-wave, THz, and optical domains, where the relative impact of any timing or phase error increases linearly with frequency (for example, switching from MHz to GHz scales amplifies the issue by a factor of 1000). Traditional time-domain systems often rely on a timing loop between transmitter and receiver, particularly in applications requiring precise phase monitoring. However, at pico- and sub-picosecond scales, technological limitations such as thermal noise further complicate synchronization. As 5G and 6G networks shift toward even higher frequencies, these issues are expected to intensify.

In addition to timing errors like jitter and drift, non-ideal parameters such as temperature variation, cable loss, and phase noise can also degrade signal fidelity. In conventional systems, these effects may propagate through the acquisition chain, affecting synchronization. However, in our dual-channel synchronization approach, operating independently of external triggering, such factors do not significantly impact the algorithm’s performance. While temperature or cable-induced variations may introduce minor amplitude or timing errors, they are effectively mitigated during post-processing. Moreover, phase noise with a symmetric distribution primarily influences the envelope calculation rather than the phase alignment critical to synchronization.

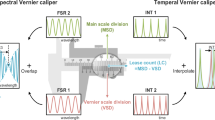

Sampling and real time oscilloscopes play an important role in signal acquisition. One of the significant differences between sampling oscilloscopes and real time oscilloscopes is that the effective bandwidth of sampling oscilloscopes can be typically hundreds to thousand times higher than the internal sampling frequency. The timing accuracy (or jitter) of a single sampling event can be up to a million times smaller than the sampling period. While sampling oscilloscopes offer considerable advantages, they have two fundamental drawbacks compared to real-time oscilloscopes. First, they require the input signal to be fully repeatable at the smallest time scales (related to the timing accuracy explained above) and second, they generally depend on external triggering. Nevertheless, a recent technology using a local oscillator with a low frequency has been introduced, allowing sampling oscilloscopes to operate independently of an external trigger. However, they must still be coupled to the signal1,2. It is worth noting that all these challenges arise for input signals with spectral components higher than a few tens of GHz. For input signals with lower spectral frequency components, however, the speed of available electronic components allows to implement accurate sampling even without external triggering. Tables 1 and 2 present a timeline of the advances in synchronization techniques in oscilloscopes and triggering.

Recent advances in synchronization techniques for sampling oscilloscopes have significantly improved the reliability and precision of waveform monitoring for repeatable, high-frequency signals. Foundational principles are well-documented in technical literature, such as the Tektronix primer, which explains how equivalent-time sampling and advanced interpolation methods enable oscilloscopes to reconstruct high-frequency signals with high fidelity8. In practice, real-time and equivalent-time sampling methods are selected based on signal characteristics, and synchronization is achieved through careful management of trigger sources, reference clocks, and signal path delays. For multi-instrument setups, precise synchronization using a high-stability reference clock and matched cabling can virtually eliminate long-term drift and minimize timing errors between channels. These best practices are critical for applications like eye diagram analysis and high-speed communications testing, where time base errors can significantly impact measurement accuracy3. Recent peer-reviewed research has further advanced these principles. Tankeliun et al.4 introduced a hybrid time-base (HTB) device for coherent sampling oscilloscopes, combining trigonometric and interpolation techniques to determine sample-time positions with high accuracy. By sampling both the test signal and a synchronous harmonic reference clock, the HTB device reduces sampling jitter by more than a factor of two and nearly eliminates drift in the equivalent time axis when phase locked. This approach, validated experimentally, marks a significant advancement for coherent sampling and waveform restoration. Compared to hardware-intensive or network-dependent solutions, our dual sampler in addition to post-processing method offers sub-picosecond synchronization with minimal hardware and software complexity, making it more accessible for high-frequency asynchronous systems.

The impact of the triggering issues and novel solutions in the acquisition of repeatable signals such as in sampling oscilloscopes, will be exemplified in this paper by means of the novel non-destructive testing (NDT) technique, transient radar methodology9,10,11.

Transient radar methodology

Wave-based techniques play a prominent role in the NDT domain. It involves various techniques such as ultrasonic investigations, X-ray imaging, laser pulse scanning, and microwave, millimeter wave or sub-THz wave scanning or imaging12,13. Microwave, millimeter wave (MMW), and THz technologies have found use in (broadband) dielectric spectroscopy, time-of-flight sensing, time-domain reflectometry (TDR), and frequency modulation continuous wave (FMCW) radar imaging. Recent literature highlights rapid growth in MMW/THz applications across diverse fields like composite material characterization, thermal barrier coatings, and noninvasive clinical monitoring14,15,16,17,18,19. The latter category of waves is particularly useful for monitoring physical and chemical changes in industrial and pharmaceutical materials, with the choice of frequency range crucially dependent on conditions and application requirements. Despite the higher resolution of sub-THz or THz imaging methods compared to ultrasound, they suffer from limited penetration depth20. Furthermore, drawbacks such as the necessity of couplant gel, prior knowledge, and ionizing radiation hinder the effectiveness of ultrasonic, spectroscopy using MMW/THz, and X-ray methods respectively21,22.

Transient Radar Methodology (TRM) is an NDT technique that utilizes narrowband electromagnetic waves to analyze multi-layer dielectric structures by extracting the thickness and electromagnetic (EM) properties of each layer of the sample under test by means of a time domain analysis9,10,11,14. Conceptually a sample under test is illuminated with a smoothly truncated sinusoidal wave of limited duration, rising from no radiation to a steady state regime and then back switched off. Along its propagation, such illuminated waves will be partially reflected at each material interface of the sample, leading to an accumulation of time-delayed reflected waves, also called propagation paths. All these partially reflected waves (propagation paths) will interfere and this complex interference signal in the time domain will compose together the full transient radar signal. To minimize EM dispersion effects induced by any material in the multi-layer sample under test, the illumination frequency band should be as narrow as possible, which is fully controlled by the rise-time of the switch controlling the output of the emitter. The rise time of this switch should be inversely proportional to the emitted carrier frequency. In general, TRM data acquisition can be done with real time or sampling oscilloscopes, depending on the required time resolution between sampling points and the cost limitations for application development. For a real-time oscilloscope, having the largest price tags, one illumination and one reflection are typically sufficient for full signal acquisition at the receiver. This is because real-time oscilloscopes capture and sample the signal continuously over time, allowing for the direct observation of the waveform as it occurs. As such, a single instance of illumination and reflection provides a complete representation of the signal23,24. Nevertheless, the minimum time resolution of real-time scopes is rather in the 5-picosecond range while for sampling oscilloscopes could be sub-picosecond without interpolation. Using a sampling oscilloscope with random equivalent time sampling, the sample under test should be repeatedly illuminated with exact the same illumination signal. During each illumination time the signal is sampled with time accuracy down to 100 fs (10 to 100 times more accurate than in real-time oscilloscopes). Combining all the samples collected with thousands of repeated illuminations results in a concatenated set of scattered measurements. The captured waveform is then used to reconstruct the signal. This process is doable when the triggering can be strictly controlled as shown in previous research10,14,25. Due to the technical limitations in varying the power of illumination, radiating transient radar signals using different frequency carriers, and most challenging of all, synchronizing and coupling the transmitter section with the receiver from a hardware perspective, differential ports, and consequently two samplers, are used instead of single-shot samplers and triggering. In this study, it is proved that input signal with a 10 GHz carrier frequency can be monitored since the triggering frequency is not larger than 2 MHz, that is operating without coupling the input signal. Using a single harmonic as a triggering signal that its frequency is one thousand or even ten thousand times smaller than the input signal for monitoring the phase of the waveform on sampling oscilloscopes or other time domain components, devices in the radio frequency range, or even the optical domain, is completely doable. For operating TRM techniques in variant power and variant frequency carriers to cope with such challenging application domains, novel system solutions are needed, where even a lack of synchronization between emitter and receiver can be handled by smart post-processing techniques. When this synchronization is lost, the captured signal can be coined as the asynchronous equivalent. A novel algorithm has been proposed to reshuffle this asynchronous signal and to convert it into a synchronous equivalent, which allows us to analyze the electromagnetic and geometric characteristics of the sample under test via the known techniques of the transient radar method14. Although a TRM system can be implemented across any frequency range, the actual system operates with a carrier frequency of 10 GHz, and the recording period is no longer than a few nanoseconds (ns). However, in the actual system, an impressive challenge arises when the indirect triggering solution is deployed to higher or lower frequency carriers, or when high radiation power is implemented11,14. Sampling issues arise due to slight variations in the timing and relevant phase and frequency of each generated signal in the repetitive cycle. This leads to asynchronous sampling, causing the data points to be spread out in time, creating a cloud-like pattern. The cloud-like signal (which could be associated with a closed eye-diagram) acquisition is an issue for the next signal processing steps as no signal modulation can be done to extract further parameters. Hence, we had to design a new system and implement novel data processing solutions that still workwith sampling oscilloscopes but donot have limitations. For the extraction of theEM and geometrical data with post-processing techniques, the waveform of the reflected signal must be recorded in synchronous mode for a few nanoseconds. In the actual system, to achieve the highest synchronization state, the sampler is triggered with an indirect triggering technique exploiting a reflective single-pole single-throw switch11,14. The advantage of using indirect triggering to synchronize the transmitter and receiver parts on the (sub-)picosecond scale is that it automatically compensates for any time shifts or delays in coupling between the transmitter and receiver. This becomes even more effective when the triggering input signal is a few MHz for a 10 GHz input signal.

After converting the asynchronous signal to its synchronous equivalent, the decomposition of propagation paths -related to the multiple partial reflections at the interfaces of the sample under test - is performed using a forward solver algorithm, which operates based on the peeling method3,4,5.

Materials and methods

The synchronization process generally involves several steps, including data acquisition, DC reduction, envelope extraction, and parameters calculation. The parameters include average frequency (faverage), frequency per sample (fs), the initial point of the signal within the considered time window (t0 − nose), time delay (td), and harmonic number (n). Finally, synchronization is performed, as explained in the corresponding section. Synchronization uses a cost function to iteratively reconstruct the synchronous signal by exploring different possibilities for the frequency and \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\). As proof of concept, a transient radar signal has been selected, while still narrow band, it is more complex than a single harmonic due to its multiple features, including rise time. This transient radar signal is used for nondestructive testing to characterize a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) sample, allowing for the extraction of its thickness and dielectric permittivity experimentally. It is worth noting that synchronization is the first step, and additional calibration operations, pre-measurements, vertical and horizontal phase injections are necessary for conducting nondestructive testing using TRM, that is described later in validation part.

Switch from synchronous to asynchronous

In our method, instead of using more complex hardware26,27,28 we exploit a conventional sampler combined with post-processing, which allows us to detect and filter outliers and significantly reduce the standard deviation. Moreover, this technique enables the detection of outlier samples caused by jitter, noise, drift, or other non-idealities, which can then be removed in the subsequent post-processing steps. However, any single-end structure cannot detect and filter outlier samples, even if it can decrease the average errors occurred. By using this technique, we are not only measuring pure single harmonic, narrowband system surrounding carrier frequency but also any signal shape that is modulated on the carrier frequency could be sampled as synchronous mode. Moreover, any narrowband, wideband, or even ultrawideband signals that are modulated using single-tone modulation can be synchronized by leveraging this technique in both high frequency microwave and optical domain. In fact, using this technique shifts the issue from the hardware domain, including inevitable non-idealities, to the mathematical domain, and then modification or removal of the sample can be implemented. Using this technique could be implemented without external triggering signals as well as internal local oscillation. Additionally, synchronization is independent from precise triggering. Most challenging issues related to the synchronization in high frequency domain such as, random jitter, systematic time-based distortion, aliasing (when the sample rate is not fast enough), high-frequency components can “fold down” into lower frequencies, causing distortion in the displayed waveform, interleave distortion, triggering issues, clock synchronization, sampling clock synchronization and insufficient samples per cycle23,26,27 could be addressable using dual single shot samplers in differential mode and post processing operation that is described further.

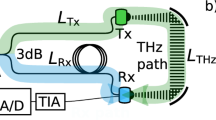

In general, using sample and hold modules or sampling oscilloscopes has lower noise floor compared to real time oscilloscopes and the real time resolution could be much lower than real time oscilloscope, however, it is appropriate for analogue applications such as senores. As we mentioned, synchronization in sampling oscilloscopes is one of serious challenge specifically for higher frequency ranges. In the transient radar hardware, the sample under test (SUT), which can vary from a single to multi-layer dielectric and or magnetic structure, undergoes illumination with a monochromatic continuous wave signal including rise time, meaning no-radiation to steady state versus time at 10 GHz. During this process, the time-dependent reflection signal from the SUT is recorded. The synchronous TRM process14 typically involves two main steps: data acquisition and extraction of the SUT’s parameters. However, in asynchronous TRM, an additional step known as synchronization of the data is introduced between these two main steps. This synchronization step is crucial for aligning the asynchronously sampled data points and reconstructing a coherent representation of the reflected signals. Extraction of the SUT’s parameters can be reliably performed14, only after this synchronization process. Figure 1 presents an overview of synchronous and asynchronous setups. In fact, instead of using an input signal and external trigger in the sampling oscilloscope, the input signal is divided into two inputs and recorded using dual single-shot samplers simultaneously with an independent external trigger.

In general, the TRM system consists of a single frequency generator, power divider, reflective Single Pole Single Throw (SPST) switch, amplifier, transmitter and receiver antennas, single-shot samplers, low-pass filters, delay creator, and a trigger module. The single frequency generator is a narrow-band voltage-controlled oscillator (VCO) that generates continuous electromagnetic waves at a frequency of 10 GHz. The power divider functions as a power splitter, providing similar amplitude and phase to each output port. The SPST switch serves two main functions in this setup: first, it enables rise time generation, which is achieved by converting the generated single harmonic from the baseband to the intermediate band. Second, it reflects the signal to trigger the single-shot sampler at the moment it toggles between conductive and non-conductive states. The amplifier increases the amplitude of signals that are radiated toward the sample under test. The transmitter and receiver antennas function as the emitter and collector of the electromagnetic waves, respectively. The single-shot sampler, also known as the sample-and-hold module, records the amplitude of the reflected electromagnetic waves during an infinitesimal time interval. The low-pass filter removes noise and improves the quality of the recorded signal. The delay creator allows the operator to record the reflected signal at specific time frames. Finally, the trigger module sends commands to the SPST switch to toggle between conductive and non-conductive states.

To synchronize this data effectively, we operate under the premise that both channels are acquiring data synchronously. In other words, if channel 1 records a measurement at time t = t1, channel 2 also records a measurement at the same time. This ensures that the data points recorded at t = t1 by channel 1 (t1,y1) and channel 2 (t1,y2) originate from the same signal repetition, sharing the same frequency, and \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) (see Fig. 2). Additionally, this technique works for any signal including single-tone as a frequency carrier thus, we supposed for each repeated input signal in the sampling oscilloscope we have the following equations for both channels. The following formulas are simple mathematical models of transient radar signals. Due to the use of a sampling oscilloscope for data acquisition, repeatability is a key factor. However, in each repetition, the screened signal initiates with its \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) which might be different from the next one due to non-ideal parameters such as noise, drift, and jitter and or having equivalent initial phase. So, we must always consider that there are two types of \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\): one refers to each repetition, and the second one, which we call the ideal \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\), is the time point that ideally should be applied to all repetitions.

Equation 1, in fact, represents a mathematical model of the transient radar signal as a sinusoidal function. For simplicity, primary phase is translated to the \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) in Eq. 1. These equations are also fit with transient radar signal that is used later in validation part. \(\:{A}_{1},\:{t}_{1},{t}_{0-nose},\:{n}_{1\:or\:2},\:and\:{f}_{s}\) represent the amplitude of the sinusoidal curve as a function of time, the moment when the sample is recorded, the initial moment of the reflected transient signal for each repetition, the integer value for the harmonic number, and the signal frequency, respectively. Figure 2 represents the scheme of two signals that could be recorded using real time oscilloscope but in sampling oscilloscope for each repetition, only one or two samples are caught and for reconstructing the signal properly using high speed, precise external trigger in picosecond or even sub picosecond time interval must be implemented otherwise the output is not clear and readable specifically for higher frequency ranges. It is worth noting the transient radar signal that we are talking about, has 10 GHz as carrier frequency and time window that is recorded is only few nanoseconds. Using this technique, recording data without dependency to accurate-precise external trigger will be implemented. From a mathematic point of view, there are three unknown parameters, including, \(\:{f}_{\text{s}}\), \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) and \(\:{n}_{1}\). Some other parameters can be determined easily in advance and injected into the post processing solution. For instance, \(\:{A}_{1}\left({t}_{1}\right)\) and \(\:{A}_{2}\left({t}_{1}\right)\) can be obtained using envelope calculation for each data point corresponding to each channel. Additionally, \(\:{t}_{d}\) can be calculated specifically for transient radar signals using the time discrepancy between two envelopes or it can be generally determined in advance for the typical dual single shot samplers. \(\:{n}_{2}={n}_{1}+{n}_{{t}_{d}}\) and \(\:{n}_{{t}_{d}}\:\)can be estimated using following formula.

The average frequency of the reflected signal is computed using either CH1- or CH2-REF-REF data. However, only the last quarter section of the signal (see Fig. 2), known as the steady-state part, is considered for this calculation, even though the frequency can be determined across the entire time window. In fact, Eq. 2 computes the estimated harmonic number corresponding to a given time delay, using the previously calculated average frequency. This is needed to narrow down the set of valid harmonic number candidates during synchronization, enabling more accurate reshuffling of asynchronously sampled data. The average frequency can be determined by using the following formula:

\(\:{A}_{1},\:{t}_{1},{t}_{0\:nose},\:n,\:and\:{f}_{s}\) represent the amplitude of the sinusoidal curve as a function of time, the moment when the sample is recorded, the initial moment of the reflected transient signal, the integer value for the harmonic number, and the signal frequency, respectively.

For every data point, the frequency is computed, yielding an array of frequencies. The mean of this array is then calculated to determine the average frequency (faverage). Additionally, the maximum and minimum values found in the array, which will be utilized later in computing the uncertainty value.

It is worth noting, due to the uncertainty in each repetition the \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) must be calculated individually. From a mathematical point of view, we need extra equation that could be cost function as follows. In other words, Eq. 3 is used to estimate the instantaneous frequency of each sample in the asynchronous signal. The output feeds into the cost function and harmonic number estimation step of the synchronization algorithm, helping to resolve phase ambiguity and align repetitions of the waveform accurately.

In this equation, f represents the illumination frequency. In fact, \(\:{n}_{1}\) is unlimited and integer quantity that in this case it can be limited to the few possibilities by having priori knowledge about carrier frequency. In fact, this cost function is used in the iterative optimization process for reshuffling the asynchronously sampled data. The cost function helps identify the best-fit harmonic number and frequency that align the sample with the reconstructed synchronous waveform. In ideal case, since the signal to noise ratio is infinite, carrier frequency is constant, and hence the harmonic number can be obtained. In reality multiple non-ideal features such as noise, jitter and drift impose slight differences from the ideal case. Nevertheless, by knowledge of the average of the carrier frequency, the order of magnitude of number harmonic for each pair of samples can be roughly estimated and finally by means of a cost function each parameter can be recalculated accurately. \(\:{n}_{1}\) for each sample point could be obtained using following formula.

Consequently, for every data point, the amplitude is obtained from the envelope of signal and then the frequency is computed, yielding an array of frequencies. The mean of this array is then calculated to determine the average frequency (f average). Additionally, the maximum and minimum values of \(\:{f}_{s}\) in the array, would be utilized later in computing the uncertainty value. The next parameter to be calculated is the \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\). The \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) represents the onset time point of the reflected signal from the front side of the SUT in transient radar application for each repetition. Although, \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) is specified parameter for transient radar signal and it must be determined accurately but for any other signal it could be considered as initial point of time window of oscilloscope’s screen. This is a core step in reshuffling the asynchronous samples into a coherent, periodic signal. By determining how far into the waveform each sample lies in terms of cycles, it enables reconstruction of the proper time sequence for signal alignment and synchronization. Now, there are two equations and two unknowns for each pair. By solving these equations, frequency and \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) can be calculated for each pair and repetition in sampling oscilloscope. And in the last step, reshuffling is applied based on obtained data. A set of two equations and two unknowns can be solved, on the condition that the time delay is not zero, otherwise you measure the exact same point on both channels, which means you cannot solve the two unknowns (generating dependent equations). Additionally, there are always two possible solutions \(\:\pi\:-x\) and \(\:x\) for a \(\:{\text{s}\text{i}\text{n}}^{-1}\) function. In the system of two equations, this gives us 4 possible solutions (actually, infinite due to the 2 \(\:\pi\:\) n). Since we use an average value for the frequency to calculate \(\:n\), an error will be made. To account for this, we calculate an uncertainty value for n based on the minimum and maximum frequency calculated in the steady-state part of signal:

In fact, Eq. 6 can show the length of possibilities for n in the following flowchart. It is obvious if SNR is high the length of uncertainty becomes short and vice versa. The uncertainty is used to bound the search space for possible harmonic numbers during synchronization. This helps limit the number of cycle candidates to test during reshuffling, reducing computation while ensuring accuracy in cases where noise or jitter affects frequency stability.

The experimental results related to the \(\:{f}_{s},\) \(\:{t}_{0-nose}\) and n and reshuffling are given in the following graphs (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7).

Validation with experimental measurements

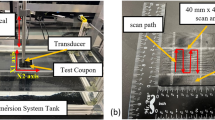

The procedure described in “Switch from synchronous to asynchronous” is a general concept, meaning any high frequency signal in any condition that modulated on single tone can be monitored using this technique independently using the higher triggering signal. However, it was only one step of calibration and pre-measurement using TRM. So, further measurements and computations are necessary for measuring the electromagnetic properties and thickness of SUT. As proof of concept, PVC sheet (50 cm × 30 cm) with a thickness of 5 cm, was selected as the sample for characterization. To reduce the environmental interference, strong absorber sheets were positioned behind the SUT. These experimental measurements have utilized the Keysight DCA-X oscilloscope (Keysight corporation, MA, USA). Signal processing was done in MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

The differential asynchronous TRM setup is shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

After running the measurement, six asynchronous datasets in three different steps were generated for further data processing including synchronization and extra computations, parameter extraction, and lastly, sample characterization.

Naming convention for datasets includes three terms. Assuming the convention of x_y_ch, first term ‘x’ refers what is in front of the current channel, ‘y’ stands for what is in front of the other channel, and ‘ch.’ represents the current channel that made the measurement (Table 3).

It is worth noting, as a first step, that the asynchronous-to-synchronous algorithm has been applied to Channel 1 REF-REF and Channel 2 REF-REF signals. For the remaining two steps related to the TRM, additional computations are performed, and there is no longer a need to convert the asynchronous-to-synchronous algorithm. In these two steps, the \(\:{t}_{0\:nose}\) and frequency for each sample point, already obtained from Channel 1 REF-REF, are applied to the REF-SAM and REF-AIR channels. It is important to note that Channel 1 remains in a fixed position throughout the three measurement steps, meaning that the reflected signal should be similar across these steps. To ensure similar signals in REF-REF-Ch.1, REF-AIR-Ch.1, and REF-SAM-Ch.1, the phase for each sample point is calculated according to the following Eq.

where φ₁ and φ₂ refer to the initial phases for REF-SAM-Ch.1 and REF-AIR-Ch.1, which should be calculated for each sample point in the relevant dataset until the signals in the column related to Ch.1 are similar across the three rows (vertical phase injection). Mathematically, we must satisfy the following equation in the recorded time window:

Based on the principle of superposition, these phase values (φ₁ and φ₂) will be applied to the horizontal datasets (horizontal phase injection), specifically SAM-REF-Ch.2 and AIR-REF-Ch.2. (Fig. 10).

Once the asynchronized signals are transformed into synchronized signals, the previously established blind algorithm for TRM14 can be implemented. This algorithm enables the calculation of electromagnetic properties and thickness of each layer within a layer-based sample under testing.

Some Tips for This Type of Calculation.

-

1)

DC reduction: Filtering out the DC offset; initially, any data pairs containing undefined values are eliminated from all datasets to maintain uniformity in the time arrays. Subsequently, the DC offset of each dataset is computed and then subtracted from the data.

-

2)

Computing the envelope for each data array: One step involves computing the envelope for each data array. Various methods exist for calculating envelopes. In this experimental study, a specific approach is employed; the total time window is divided into one hundred time slots, and the average of the last twenty highest/lowest values within each slot is regarded as a single sample point for the upper/lower envelope.

-

3)

Drift compensation stage: In the drift compensation stage, we address drift that may occur during the measurements. The drift calculation is performed on channel 1, as the same signal is consistently measured there (see Fig. 11). To compute the drift, one of the envelopes is incrementally shifted in both directions, and the discrepancy between the two envelopes is determined. The shift resulting in the smallest error is deemed the correct amount of drift. Specifically, CH1-REF-REF is designated as the reference set, and the envelopes of CH2-REF-AIR and CH2-REF-SAM are adjusted to calculate the drift.

If the signal being shifted happens after the reference signal, the resulting time delay is considered negative. Conversely, if the signal occurs before the reference, the delay is deemed positive. This principle is exemplified in Fig. 11, where tdrift 1 is negative and tdrift 2 is positive. Following this, it is assumed that any drift observed on channel 1 is also present on channel 2, and thus the same correction is applied to channel 2, as illustrated in Fig. 11. This assumption is fully supported using a single clock for both channels in the oscilloscope setup.

-

4)

Effective angle computation: Although the simplest calculation of electromagnetic properties of SUT would be measured since the transmitter antennas and receiver have zero-degree angles due to avoiding phase error from output aperture of antennas, and decreasing complexity of refraction impact, etc., increasing angle leads to improving SNR. As a result, the angle must be near zero, however, it can still impact output quantitative results. The thickness calculation is directly correlated with the time of flight corresponding to each propagation path9. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the effective angle between the transmitter and receiver antennas through additional calibration and calculations. The angle at which the signal is transmitted and received plays a vital role in determining the thickness of the sample: a greater angle results in a longer signal path through the material and build-up phase error etc. While the angle can be adjusted by manipulating the antennas, it is imperative to calculate the angle based on the data to obtain the true effective angle (see Fig. 12).

As illustrated in Fig. 12, the calculation of the effective angle can be done by further calibration. In fact, by changing the distance between the ideal reflector and transceiver, reflector, we can obtain two new signals being known as near REF and far REF. Taking the triangle of abc into account, we can write the following equation:

In a similar way, we can write the following equation for the triangle acd:

We also know that:

While we lack direct measurements of a, b, or d, we possess the differences between them; the green line in Fig. 12 represents y = a - b, and the yellow line represents z = d – a. Therefore:

Now, we can express b and d in terms of a to establish two equations with two unknowns (a and \(\:\alpha\:\)):

and:

Finally, the effective angle can be calculated by:

Results

Propagation paths, complex permittivity and thickness measurements

After synchronous conversion (Fig. 13), three sets of signals are generated: REF, SAM, and AIR. This means that after synchronization, data from the first channel, which was previously related to the reflector, is no longer needed. The AIR signal, generated due to crosstalk from the antenna, is subtracted from both the REF and SAM signals. Finally, the decomposition of propagation paths is performed.

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed synchronization algorithm under non-ideal conditions, we performed error vector diagram simulations using synthetic datasets. The simulations assumed an amplitude noise standard deviation of 0.2 and a phase noise standard deviation of 15 degrees. Two datasets were analyzed: one processed using the synchronization algorithm and another left uncorrected. The resulting error vector diagrams (see Fig. 14) show a clear reduction in distortion when the algorithm is applied, confirming its resilience to amplitude and phase noise.

To extract the first propagation path (PP), the initial segment of the envelope of the REF signal is matched to the initial segment of the envelope of the SAM signal. This segment contains only the first PP, free from interference from other PPs that appear later in the signal. The portion used for data matching spans from the nose (head of the first propagation path) of the reference signal to 40% of the SAM signal. The ideal nose is determined by the intersection of the AIR signal and the REF signal, occurring at 40,011 ns, as shown in Fig. 15.

Through an iterative process, the envelopes of the REF and SAM signals are matched, yielding the amount of reflection illustrated in Fig. 15. Next, the optimal phase is calculated by injecting a phase into the REF signal and comparing it to the SAM signal, based on the TRM algorithm explained in9. This comparison is performed using the initial part of the SAM signal, which corresponds to approximately 40% of the total SAM data (Fig. 16). The first propagation path is defined as the reflection coefficient multiplied by the REF signal, which already includes the appropriate phase.

The REF, SAM, and SAM without the first PP are shown in Fig. 17.

With the first PP obtained, we can also calculate the dielectric permittivity of the sample, which allows us to determine the speed of light within the material. To determine the thickness of the SUT, we need to identify the nose of the second PP (the head of the second PP). By multiplying the corrected speed of light by the time difference between the noses of the first and second PPs, we can calculate the thickness of the SUT.

After subtracting the first PP from the sample signal, we can repeat the same process4. However, the nose of the REF signal no longer aligns with the nose of the SAM signal. Our iterative process now involves matching two parameters amplitude and nose. Figure 18 shows the outcome of this process, indicating that the matching is not as accurate as it was for the first propagation path. As more propagation paths are extracted, the results become less reliable. The nose is determined to be at 40.570 ns.

Next, the phase is matched again. Currently, the outcome of this process is not as expected, as shown in Figs. 18 and 19. This discrepancy may be due to inaccuracies in previous processes or the need for improved phase matching.

Using the noses of PP1 and PP2 (see Fig. 20), we can calculate the material’s thickness, enabling us to evaluate the effectiveness of our algorithm.

Based on the results obtained, the PVC thickness is determined to be 5.29\(\:\pm\:0.03\) cm. However, by considering the angle between the emitter and receiver, we can further refine the speed of light calculation, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the thickness measurement. This modification resulted in a thickness of 4.83\(\:\pm\:0.03\) cm.

Discussion and conclusion

In the realm of signal analysis, synchronization plays a pivotal role in ensuring accurate and reliable measurements. Synchronization, particularly in the context of electromagnetic signals, is crucial for aligning the signal phases and frequencies, thereby enabling precise sampling with sampling oscilloscopes. When signals are not properly synchronized, the resulting data can be plagued by phase jitter, frequency drift, and timing errors, which can obscure the true characteristics of the signal and lead to erroneous conclusions. Proper synchronization facilitates the coherent sampling of signals, allowing for the clear and accurate representation of signal parameters such as amplitude, phase, and frequency. This is especially important in high-frequency applications where even minor discrepancies can significantly impact the performance and interpretation of the measured data.

The central innovation lies in the development and implementation of a dual single-shot sampler architecture combined with a mathematical post-processing algorithm that converts asynchronously acquired data into a synchronized waveform. Unlike traditional systems that rely on hardware-based synchronization and high-speed external triggers, this method reshapes the synchronization challenge into a software-driven problem, allowing for flexible, accurate signal reconstruction with minimal hardware complexity. Scientifically, this study contributes a generalizable asynchronous-to-synchronous conversion framework capable of correcting jitter, drift, and phase distortions across repetitive signal measurements. It proves that synchronization can be reliably achieved even when the triggering signal is orders of magnitude lower in frequency than the input signal (e.g., using a 2 MHz trigger to capture a 10 GHz carrier). Experimental validation using a transient radar signal demonstrated successful extraction of complex dielectric permittivity and material thickness of a 5-cm polyvinyl chloride (PVC) sample. The technique yielded results with high accuracy, reducing relative error from 5.8 to 3.4% after refining the effective transmission angle. Furthermore, this method is not restricted to narrowband systems; it can be extended to any signal, narrowband, wideband, or ultrawideband, modulated on a single-tone carrier in both the microwave and optical domains. By decoupling synchronization from hardware constraints, this work offers a foundational advancement for future non-destructive testing systems and high-frequency signal analysis tools, enabling enhanced measurement precision, reduced system complexity, and broader frequency adaptability.

As proof of concept, experiments were conducted on a 5-cm thick PVC using an asynchronous TRM setup at almost 10 GHz. Following synchronization, the traditional transient radar methodology was employed to extract the dielectric permittivity and thickness of the PVC without using priori knowledge. This involved decomposing the reflection response of the PVC into several sub-reflections, known as propagation paths, which are generated when electromagnetic waves encounter an interface with an impedance mismatch. Through this method, the first and second propagation paths of the PVC were identified. The first propagation path provides information about the reflection coefficient of the SUT, which is used to calculate the speed of light in that medium. Additionally, the leading edge of the first propagation path indicates the moment when the electromagnetic waves reach the first interface (front side of the PVC). The second propagation path, representing the back side of the PVC (second interface), allows for the calculation of the time difference between the leading edges of the first and second propagation paths. This time difference is subsequently used to determine the thickness of the PVC. The results showed a dielectric permittivity of (2.55 ± 0.02) – (0.23 ± 0.01) j and a thickness of 5.29 ± 0.13 cm resulting in a relative error of 5.8%. After refining the speed of light based on the angle between the transmitter and receiver, the relative error decreased to 3.4%. The synchronization process represents a significant advancement in transient radar methodology, offering researchers the capability to conduct measurements in asynchronous mode. This innovation allows for higher illumination power, increased penetration depth, and greater flexibility in frequency adjustments, among other benefits.

In our long-term vision, we aim to push this technology forward by developing a system that renders sampling oscilloscopes independent of external triggering for millimeter wave range or higher using dual samplers instead of single sampler and external triggering. Although this concept is currently focused on narrowband systems and relatively high frequency microwave, it can address the synchronization of any narrowband, wideband, or even ultrawideband signals modulated using single-tone modulation in both microwave and optical domain. As mentioned, using reshuffling during the post-processing stage allows for noise reduction and signal stabilization without requiring precise single-shot samplers. Future developments will be necessary to extend its applicability to wideband and ultra-wideband systems without limitations. In this work, we address asynchronization issues in single tone modulated signals, which are validated through experimental tests of transient radar signals3.

Data availability

The derived data supporting the findings of this study, in addition to the processing algorithms, are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Remley, K. A. & Williams, D. F. Sampling oscilloscope models and calibrations. In: IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest, 2003: 8–13 June 2003 2003; : 1507–1510 vol.1503. (2003).

Electrical Sampling Modules Datasheet. https://www.tek.com/en/datasheet/electrical-sampling-modules-datasheet

How to Synchronize 4 5. and 6 Series MSO Oscilloscopes for Higher Channel Count https://www.tek.com/en/documents/technical-brief/how-to-synchronize-4-5-and-6-series-mso-oscilloscopes-for-higher-channel-count

Tankeliun, T., Zaytsev, O. & Urbanavicius, V. Hybrid Time-Base device for coherent sampling oscilloscope. Meas. Sci. Rev. 19 (3), 93–100 (2019).

He, S. et al. Time synchronization network for EAST poloidal field power supply control system based on IEEE 1588. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 46 (7), 2680–2684 (2018).

Kaviani, A. S. Dual-edge synchronized data sampler. In., vol. US 7,190,196 B1 USA: Xilinx Inc; (2004).

Pham, T. H., Prasad, V. A. & Madhukumar, A. A hardware-efficient synchronization in L-DACS1 for aeronautical communications. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. VLSI Syst. 26 (5), 924–932 (2018).

Oscilloscope Systems and Controls. Vertical, Horizontal & Triggering Explained https://www.tek.com/en/documents/primer/oscilloscope-systems-and-controls

Pourkazemi, A., Tayebi, S. & Stiens, J. H. Error assessment and mitigation methods in transient radar method. Sensors 20 (1), 263 (2020).

Pourkazemi, A., Tayebi, S. & Stiens, J. H. Fully blind electromagnetic characterization of deep Sub-Wavelength (λ/100) dielectric slabs with low bandwidth differential transient radar technique at 10 ghz. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 70 (3), 1651–1657 (2022).

Pourkazemi, A. & Stiens, J. Characterization of multilayer structures. In, EP3106861A1, 1–31 (2015).

Hui, R. & O’Sullivan, M. Chap. 2 - Basic Instrumentation for Optical Measurement. In: Fiber Optic Measurement Techniques. Edited by Hui R, O’Sullivan M. Boston: Academic Press; : 129–258. (2009).

Korzh, B. et al. Demonstration of sub-3 Ps Temporal resolution with a superconducting nanowire single-photon detector. Nat. Photonics. 14 (4), 250–255 (2020).

Pourkazemi, A., Stiens, J. H., Becquaert, M. & Vandewal, M. Transient radar method: novel illumination and blind electromagnetic/geometrical parameter extraction technique for multilayer structures. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 65 (6), 2171–2184 (2017).

Jincan, Z. et al. A rigorous peeling algorithm for direct parameter extraction procedure of HBT small-signal equivalent circuit. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 85 (3), 405–411 (2015).

Kumar, V. & Ghosh, J. Phase noise analysis performance improvement, testing and stabilization of microwave frequency source. J. Electron. Test. 40 (3), 387–403 (2024).

Telba, A. A. Jitter and Phase-Noise in High Speed Frequency Synthesizer Using PLL. In: Transactions on Engineering Technologies: 2019// ; Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019: 281–288. (2019).

Gholizadeh, S. A review of non-destructive testing methods of composite materials. Procedia Struct. Integr. 1, 50–57 (2016).

Tonouchi, M. Cutting-edge Terahertz technology. Nat. Photonics. 1 (2), 97–105 (2007).

Shen, Y. C., Upadhya, P. C., Linfield, E. H., Beere, H. E. & Davies, A. G. Terahertz generation from coherent optical phonons in a biased GaAs photoconductive emitter. Phys. Rev. B. 69 (23), 235325 (2004).

Ping Gu, P. G., Masahiko Tani, M. T., Masaharu Hyodo, M. H., Kiyomi Sakai, K. S. & Takehiro Hidaka, T. H. Generation of cw-Terahertz radiation using a Two-Longitudinal-Mode laser diode. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 37 (8B), L976 (1998).

Smet, J. H., Fonstad, C. G. & Hu, Q. Intrawell and interwell intersubband transitions in multiple quantum wells for far-infrared sources. J. Appl. Phys. 79 (12), 9305–9320 (1996).

Baek, I. H. et al. Real-time ultrafast oscilloscope with a relativistic electron bunch train. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 6851 (2021).

Williams, D., Hale, P. & Remley, K. A. The sampling oscilloscope as a microwave instrument. IEEE. Microw. Mag. 8 (4), 59–68 (2007).

Tayebi, S. et al. A novel approach to Non-Destructive rubber vulcanization monitoring by the transient radar method. Sensors 22 (13), 5010 (2022).

Fontaine, N. K. et al. Real-time full-field arbitrary optical waveform measurement. Nat. Photonics. 4 (4), 248–254 (2010).

Hussain, S. A. et al. Sub-attosecond-precision optical-waveform stability measurements using electro-optic sampling. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20869 (2024).

Jargon, J. A., Hale, P. D. & Wang, C. M. Correcting sampling oscilloscope timebase errors with a passively Mode-Locked laser phase locked to a microwave oscillator. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 59 (4), 916–922 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The VUB has partially supported this work with the SRP (Strategic Research Program) LSDS and the IOF-GEAR TECH4HEALTH project funding and ETRO.RDI BAS funding and SB Ph.D. fellow at FWO” (“SB-doctoraatsbursaal van het FWO”) and Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek—Vlaanderen, Research Foundation—Flanders, project number: 1S51124N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., J.S.; methodology, A.P., F.A.; validation, F.A., A.Z., M.GH., S.T.; data curation, A.P., F.A.; writing—original draft preparation A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P., S.T., F.A., A.Z., M.GH., J.S.; visualization, S.T.; supervision, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pourkazemi, A., Tayebi, S., Akbarian, F. et al. Asynchronous to synchronous waveform conversion for high frequency microwave and optical signals without external triggering. Sci Rep 15, 25291 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11548-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11548-z

Keywords

- Asynchronous-to-synchronous waveform conversion

- Complex permittivity and geometry of sample under test

- Determining

- Forward solver

- High-frequency

- Independence from external triggering

- Microwave and optical signals

- Narrowband

- Wideband

- Ultrawideband signals

- Non-destructive testing

- Sampling oscilloscope

- Single-tone modulated signal

- Time-of-flight

- Transient radar methodology

- Waveform acquisition