Abstract

Access to abundant greenness and low levels of air pollution have been widely recognized as contributing to a multitude of positive health outcomes. However, the empirical evidence elucidating the impact of air pollutants on the disease burden associated with dementia, as well as the potential modifying role of greenness, remains scarce. This ecological study aimed to explore the relationship between particulate matter with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5) and ozone with the disease burden attributable to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementia, and further discuss the role of greenness on this association across 162 countries globally. We acquired data on the disease burden of AD and other dementias, along with air pollutant concentrations (PM2.5 and ozone), from the Global Health Data Exchange. We used the satellite-derived annual average normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and enhanced vegetation index (EVI) sourced from the MOD13A3 product, to quantify country-level exposure to greenness. A generalized linear mixed model based on penalized quasi-likelihood was employed for statistical analysis. Additionally, stratified analysis by greenness was performed to discuss the effect modification. In the fully adjusted model, we observed that per 10-unit increment in PM2.5 and ozone was positively associated with a 2.0% and 1.9%, 2.8% and 9.5%, 2.2% and 6.7% increased risk of incidence, death, and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) rate, respectively, for AD and other dementias. These associations were found to be more pronounced in countries with lower socio-demographic index and gross national income. In areas with high levels of greenness, both PM2.5 and ozone were observed to be associated with a diminished risk of disease burden related to AD and other dementias. Our findings provide evidence of a detrimental association between PM2.5 and ozone exposure and the disease burden of AD and other dementias, particularly in low-income countries. Moreover, our results suggest that higher levels of greenness exposure may have a modifying effect, mitigating the adverse impacts of air pollutants on these outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to Alzheimer’s Disease International, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias are the seventh leading cause of death and there are more than 55 million people worldwide who have been diagnosed, this number is estimated to rise to 78 million by 2030 and 139 million by 20501. In 2019, the global cost of dementia was estimated to be US$ 1.3 trillion, and these costs are expected to surpass US$ 2.8 trillion by 2030 as both the number of people living with dementia and care costs increase (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia). Dementia is highly prevalent in China, and the number of dementia in China ranks first in the world, with about 15.1 million elderly suffering from dementia, of which 9.8 million are patients with AD2. Therefore, identifying modifiable risk factors is particularly important to prevent AD and other dementias and reduce the economic burden of the disease.

A growing number of evidences support the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Lancet Commission on potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia. Of these, air pollution is an emerging risk factor3. Air pollutants can directly trigger neuroinflammation changes and oxidative stress in the brain, increasing the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and ultimately leading to dementia and cognitive decline4. Evidence suggested a positive association between fine particulate matter (PM) less than 2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5) and AD and other dementias5. Globally, about 28% of deaths and 30% of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) associated with the total burden of dementia in 2015 were caused by ambient PM2.5 pollution, with the largest increase being in China, which increased by 758 thousand additional DALYs from 2000 to 2015, according to a systematic review6.

Natural environments can improve cognitive function by reducing stress and restoring attention, and some studies have shown an association between higher levels of residential greenness and better cognitive function7. For example, a cohort of 249,405 U.S. Medicare beneficiaries from Florida, found that higher neighborhood greenness may be associated with lower odds of AD and related dementias8. As to the mechanism, access to more greenness can reduce mental stress by promoting physical activity and social cohesion and mitigating the adverse effects of air pollution9.

Currently, relatively few studies investigating the impact of greenness on the relationship between air pollutants and the global disease burden of AD and other dementias. To address this gap, we conducted an ecological study with the primary objectives of (1) examining the association between air pollutants and the global disease burden of AD and other dementias, and (2) assessing the potential modifying effect of greenness on this association.

Methods

All data in the study were obtained from publicly available sources. A summary of the description and data source of the outcomes, air pollutants, greenness, and potential covariates was provided in Table S1.

Definition of AD and other dementias

AD and other dementias were defined using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III, IV, or V, or the international classification of diseases (ICD), tenth revision (ICD-10: F00-F02.0, F02.8-F03.9, G30-G31.1, G31.8-G31.9) and ninth revision (ICD-9: 290-290.9, 294.1-294.9, 331-331.2).

Disease burden of AD and other dementias

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database encompasses comprehensive data on the global burden of 369 diseases and injuries, along with 87 risk factors, across 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019, which can be publicly accessed from the website of Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) (Available at: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/). For the purpose of our study, we collected data on the incidence, death, and DALY due to AD and other dementias. These data were sourced from the GBD database and covered a sample of 162 countries worldwide, spanning the years 2010, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

Air pollutants measurement

We acquired the most extensively studied air pollutants in GBD database, namely, PM2.5 and ozone. Exposure to PM2.5, defined as population-weighted annual average mass concentration of PM2.5 in a cubic meter of air, was estimated from satellite data on aerosols in the atmosphere and calibrated to observations from ground monitors. Exposure to ozone, defined as the highest seasonal average eight-hour daily maximum concentration, in parts per billion (ppb), was estimated based on a chemical transport model of satellite data using Bayesian maximum entropy. The detailed methods of estimations of PM2.5 and ozone have been released in the previous study10. In addition to the GBD sources, we also collected the population-weighted PM2.5 (POP-PM2.5) and geographically-weighted PM2.5 (GEO-PM2.5) from atmospheric composition analysis group. The estimation of PM2.5 concentrations involved a comprehensive integration of data from satellite-based, simulation-based, and monitor-based sources, using geographically weighted regression to provide a robust and accurate assessment11.

Greenness measurement

We utilized country-level normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and enhanced vegetation index (EVI) data obtained from the Terra Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) to evaluate the greenness exposure. Specifically, we employed the MOD13A3 product, which provides global monthly NDVI and EVI layers at a spatial resolution of one kilometer (km). The NDVI and EVI values range from − 0.2 to 1.0, with negative values representing cloud cover, water bodies, or snow. Higher values approaching 1.0 indicate greater greenness. We downloaded MOD13A3 product images with HDF format in January, April, July, and October to consider the seasonal variation for each year. There are 292 images on average to cover the global area. Over a six-year period, a total of 7008 images (6 years * 4 months * 292 images) were downloaded and processed. Subsequently, country-level mean values of NDVI and EVI were extracted from these vegetation layers.

Other covariates

According to prior knowledge, several country-level covariates associated with AD and other dementias were collected for model adjustment in this ecological study, including demographic characteristics, socioeconomic variables, medical service, meteorological factors, and behavior factors. For demographic characteristics, we included population density (person/sq. km.), males (the proportion of males, %), and older population (the proportion of older adults aged over 65 years old, %). For socioeconomic variables, we included urban population (the proportion of urban population, %), primary education (years), SDI (socio-demographic index), and GNI (gross national income, current US$). SDI is a composite indicator of total fertility rate under the age of 25, mean education for those ages 15 and older and lag distributed income per capita. The value of SDI ranges from 0 to 1, in which 1 value indicating high income per capita, high education, and low total fertility rate. In GBD databases, countries are divided into five subgroups: low, low-middle, middle, high-middle, and high SDI. GNI reflects a nation’s economic level and is considered a more accurate indicator for some nations than gross domestic product. GNI per capita is calculated using Atlas methodology. Countries are classified into four groups based on GNI per capita: low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high income. For medical service, we collected hospital beds and physicians per 1,000 people. For meteorological factors, we considered annual mean temperature (℃) and precipitation (mm). We also collected smoking (the prevalence of current tobacco use in adults, %) and alcohol (total alcohol consumption per capita in 15 + years of age, liters) data.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics of quantitative variables were expressed as minimum, the 25th percentile, median, the 75th percentile and maximum.

To avoid multicollinearity, Spearman correlation between the candidate covariates was examined. We kept only one covariate if two covariates were highly correlated (rs > 0.7). Then, we fitted a generalized linear regression model to detect multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF). A VIF greater than 10 indicated that multicollinearity might be problematic. Based on the Spearman correlation coefficients and VIFs (Table S2 and Table S3), we chose to adjust for the covariates in the models, including males, older population, primary education, urban population, population density, calendar year, smoking, alcohol, hospital beds, mean temperature, and NDVI.

We adopted a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) based on penalized quasi-likelihood (PQL) estimation procedure with a random intercept for countries to investigate the association between pollutants and disease burden of AD and other dementias. The dependent variable included incidence cases, death cases, and DALYs due to AD and other dementias, respectively. We included a log population offset in the model. We fitted four models through adjustment for the combination of different covariates. Specifically, model 1 adjusted male, older population, primary education, urbanization rate, population density, and calendar year. Model 2 further added smoke and alcohol for adjustment to model 1. Model 3 further added hospital beds to model 2, and model 4 additionally added mean temperature and NDVI to model 3. The rate ratio (RR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) for per 10-unit increment in PM2.5 and ozone was reported.

We conducted a series of stratified analyses to examine whether the associations varied by SDI and GNI. For SDI, we categorized the data into three groups: low, middle (including low-middle, middle, and high-middle groups), and high SDI. Additionally, GNI was dichotomized into low income (including low and lower-middle groups) and high income (including upper-middle and high groups). To further explore the effect modification of greenness, we analyzed the associations between each pollutant exposure and disease burden separately within the quantile groups of greenness indicators.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to ascertain the robustness of our findings. Firstly, we reran the primary model, substituting the exposure variable for PM2.5 with both POP-PM2.5 and GEO-PM2.5 to assess their individual impacts as alternative indicators. Secondly, we replicated the effect modification analysis by employing the EVI values as an alternative measure of greenness.

All the statistical analyses and visualization were performed using R statistical software, Version 4.0.3 (University of Auckland, New Zealand) with glmmPQL function in MASS package (for main analysis) and ggplot function in ggplot2 package (for visualization). P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Research ethics board approval was not required because all data were publicly available and aggregated at the country level.

Results

Descriptive statistics

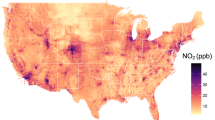

Table 1 presented the descriptive statistics of all candidate variables. During the study periods, the median values of global incidence rate, death rate and DALY rate due to AD and other dementias were 55.52 (IQR 111.96), 12.48 (IQR 23.6), and 206.94 (IQR 372.12) per 100,000 population, respectively. Global spatial distribution showed that the highest incidence rate, death rate, and DALY rate due to AD and other dementias in Japan in 2017, followed by Italy, while Qatar and the United Arab Emirates had the lowest rates (Figure S1, S2, and S3). Figure 1 also visualized the spatial distribution of country-level greenness, PM2.5, and ozone in 2017. The median values of NDVI and EVI during the study periods were 0.56 and 0.33, respectively. Greenness density is more prominent in Oceania and America. The median values of PM2.5 and ozone during the study periods were 23.13 ug/m3 and 39.96 ppb, respectively. The average concentrations of PM2.5 and ozone were higher in countries throughout Asia and Africa, with lower in Europe, Oceania and America regions.

Spatial distribution of country-level (a) normalized difference vegetation index, (b) enhanced vegetation index, (c) fine particulate matter, and (d) ozone in 2017. The map was generated using R statistical software, Version 4.0.3 (University of Auckland, New Zealand) with ggplot function in ggplot2 package.

The distribution of annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 and ozone was detected in high-level group of greenness compared to low-level group of greenness (Table S4 and Table S5). The spearman correlations between air pollutants and greenness were shown in Table S6, with coefficients ranging from − 0.36 to -0.40, suggesting negative and moderate correlations.

Association of air pollutants and greenness with disease burden of AD and other dementias

Table 2 presented the stepwise adjustment of models through the combination of candidate covariates. All the models suggested a positive association of PM2.5 and ozone with disease burden of AD and other dementias, with statistically significance. In the fully adjusted model, we found that 10-unit increment in PM2.5 and ozone were associated with 2.0% (RR: 1.020, 95% CI: 1.014, 1.026) and 1.9% (RR: 1.019, 95% CI: 1.010, 1.029) increased risk of incidence rate due to AD and other dementias, and with 2.8% (RR: 1.028, 95% CI: 1.016, 1.039) and 9.5% (RR: 1.095, 95% CI: 1.077, 1.114) increased risk of the death rate, as well as 2.2% (RR: 1.022, 95% CI: 1.014, 1.030) and 6.7% (RR: 1.067, 95% CI: 1.054, 1.080) increased risk of DALY rate, respectively.

We observed a significant negative association between greenness and dementia when greenness was at moderate levels. This suggested that there might be a non-linear relationship between greenness and dementia risk (Table S7).

Stratified analyses by SDI, and GNI

When stratified by SDI, our results revealed that the RRs associated with air pollutants and the disease burden of AD and other dementias were notably higher in low SDI countries compared to those in middle or high SDI categories. Similarly, the estimated effects were more pronounced in countries with low GNI, in contrast to those with high GNI. The detailed results obtained from these stratified analyses are clearly illustrated in Fig. 2.

Forest plots of stratified analyses by SDI, and GNI on per 10-unit increment in PM2.5 and ozone. Except for the stratified covariates, all the stratified analyses were adjusted for males, older population, primary education, urban population, population density, calendar year, smoking, alcohol, hospital beds, mean temperature, and NDVI. Abbreviation: DALY, disability-adjusted life years; CI, confidence interval; SDI, socio-demographic index; GNI, gross national income.

When stratified by SDI and GNI, we found that the association between NDVI and dementia was stronger at lower levels of SDI and GNI (Figure S4).

Effect modification of greenness exposure

To test whether greenness modified the effect of pollutants on disease burden, we conducted the stratified analyses based on the quantile groups of greenness (Fig. 3). We found that both PM2.5 and ozone were observed to be associated with a diminished risk of disease burden related to AD and other dementias in areas with high levels of greenness.

Estimated effects of air pollutants on disease burden of AD and other dementias across NDVI exposure quantiles. All the models were adjusted by males, older population, primary education, urban population, population density, calendar year, smoking, alcohol, hospital beds, and mean temperature. Abbreviation: DALY, disability-adjusted life years; CI, confidence interval; NDVI, normalized difference vegetation index.

Sensitivity analysis

When POP-PM2.5 and GEO-PM2.5 were utilized as exposure variables, the results maintained significance, with effect estimates of RR ranging from 1.016 to 1.031 across three measurements of disease burden in the fully adjusted model (Table S8). This robustness in the findings underscores the consistency of the associations observed, regardless of the specific PM2.5 metric used. Furthermore, in the analysis where the EVI was employed as an alternate indicator of greenness, we observed consistent results regarding the effect modification by EVI (Figure S5).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively assess the relationship between air pollutants and the global disease burden due to AD and other dementias, while also examining the modifying effects of greenness on this association. We identified a significant positive correlation between annual average concentrations of PM2.5 and ozone exposure with the disease burden of AD and other dementias. Furthermore, in areas with high levels of greenness, a notable attenuation in the association between PM2.5 and ozone exposure and the disease burden related to AD and other dementia was observed. Specifically, the effect estimates for these air pollutants became statistically insignificant or even reversed in high-level greenness.

Our results revealed a positive correlation between PM2.5 exposure and the disease burden due to AD and other dementia, aligning with the findings of numerous previous studies that have consistently supported the detrimental effects of PM2.5 on dementia. For instance, a population-based cohort study, which included 257,816 incident cases of dementia residing in Canada, reported a significant positive association between PM2.5 concentrations and the incidence of dementia12. Similarly, a study conducted using data from the UK Biobank, encompassing 187,194 individuals, found a robust and consistent link between PM2.5 exposure and increased risks of all-cause dementia and AD13.

Currently, evidence examining the relationship between ozone exposure and the risk of dementias is limited and inconclusive. Our results indicating an adverse effect of ozone on dementia outcomes were consistent with a large cohort of 3.5 million adults from Canada14. However, Chen et al.12 found no association between ozone and dementia incidence. Interestingly, a nationwide, population-based cohort study with a larger sample size (over 2 million incident cases) found a protective role of ozone in bi-pollutant and tri-pollutant models15. The authors thought the explanation of the protective effect might be due to the collinearity among the pollutants, and the effect of ozone was not supported.

Findings on the association of greenness with dementias outcome remained mixed and inconclusive. In a longitudinal study from Australia16 access to more tree canopy was associated with reduced risk of dementias measured by hospital and death records, but an opposite correlation was observed for dementias measured by anti-dementia medications. A large cohort study from Belgium demonstrated that surrounding greenness was related to a reduction in AD mortality17. In contrast, Klompmakera et al.18 failed to detect any association of greenness with dementia mortality in a Dutch national health survey. Our study revealed a notable negative correlation between greenness and dementia at moderate levels of greenness; however, this association became weak or even non-significant at higher levels, suggesting a non-linear pattern. This finding aligned with the results of a dose-response meta-analysis19.

Our stratified analysis by economic level suggested that the association was more pronounced increase in dementia disease burden in countries with lower income. Similarly, a prospective cohort study from Chinese older adults found that the association between PM2.5 and cognitive function was stronger in lower prefecture-level GDP20. One reason was that countries with lower socioeconomic status experienced higher concentrations of air pollutants, such as 37.66 ug/m3 (low GNI) vs. 22.14 ug/m3 (high GNI) for annual average PM2.5 concentration in our study.

Several studies attempted to deeply investigate the potential mechanisms regarding PM2.5 exposure and AD and other dementias. Neuroinflammation-related microglial activation has been identified as a major factor in the pathogenesis of AD and other dementias21. Shou Y et al.22 summarized four known pathways which PM2.5 may impact the central nervous system (CNS) and development of dementia. First, PM2.5 enters into the lungs and the vascular system, affecting CNS through those systemic diseases and peripheral inflammation, leading to neuroinflammation. Second, PM2.5 can pass directly through the olfactory nerve, causing damage to the blood-brain barrier and potentially causing neuroinflammation. Third, microbiota alteration by PM2.5 exposure may also influence AD-related brain function by gut-brain axis information transmission. Fourth, PM2.5 is inferred to lower the methylation of genome, including some vital genes incorporated in the process of AD, such as apolipoprotein E.

Inflammation and oxidative stress have generally been hypothesized to be the basic pathophysiologic pathways through which ozone damages cognitive function23. Exposure to ozone may induce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from the lungs24. These cytokines may also cross the blood-brain barrier and reach the brain, and lead to active microglia, contributing to oxidative stress and inflammation in some brain areas25.

Several epidemiological studies have demonstrated the attenuated effect of greenness on the association between air pollutants and other outcomes. A prior study from Canadian cohort showed that the effects of PM2.5 on all non-accidental cause mortality were attenuated among those residing in greener areas than those in less green26. However, few studies discussed the joint effects of air pollutants and greenness on dementias outcome. Only one study from a population-based cohort study in Canada that directly examined effect modification of greenness on the association between air pollutants and dementias found that greenness attenuated the effects of air pollution on both non-AD dementias27. Our study suggested no association between air pollutants and dementia, or even a protective effect at the highest greenness level (Q4). The protective effects in highest greenness quartile (Q4) may be attributed to vegetation’s multifaceted mitigation mechanisms. Dense vegetation has the capacity to efficiently sequester PM2.5 via stomatal deposition processes28. Furthermore, specific tree species emit biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that interact with ozone29. Additionally, canopy shading can decrease temperature-dependent formation of secondary pollutants30.

Greenness has been linked to reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases, increased physical activity and social connectedness, and attenuated negative impacts of air pollution31. These have been identified as influencing factors for cognitive decline, and could be mechanisms which may underlie greenness’ relationships to AD and other dementias. For example, greenness encourages physical activity, which leads to an increase in antioxidant capacity and induce of anti-inflammatory response32. Trees or vegetation may absorb nitrogen oxides, ammonia, sulphur dioxide, and ozone and filter particulates by trapping them in their leaves and bark33.

There are some limitations in this study that should be mentioned. First, we conducted a global-level analysis to investigate the relationship of air pollutants on the disease burden of AD and other dementias, as well as the modifying effect of greenness on this relationship. While this approach allowed us to examine trends and patterns across different countries, we also acknowledge that it has its limitations. Specifically, the use of country-level mean values for air pollution and greenness may not accurately capture individual exposure, as there can be significant variations within countries. This is particularly important to consider when interpreting our results, as individual exposure to air pollution and greenness can vary greatly depending on factors such as geography, lifestyle, and socioeconomic status. To address this limitation, we recommend that future studies aim to collect more detailed and individualized data on air pollution, greenness, and the disease burden of AD and other dementias. This could include, for example, using personal monitoring devices to measure air pollution exposure or collecting data on individuals’ daily activities and environments to better understand their exposure to greenness. Second, greenness indicators derived from satellite images based on a top-down and bird’s eye view approach could not fully capture the total green of the land surface. Moreover, vegetation indices, like NDVI and EVI, could not differentiate the composition of green spaces (e.g. parks, forests, and agricultural land) and the structure of vegetation (e.g. shrubs, grass, canopy). Third, we could not distinguish the subtype of dementias. Previously, studies suggested more highly positive association between air pollutants and AD, but less significant for non-AD dementias. For example, a comprehensive meta-analysis involving 80 studies covering 26 countries found that exposure to PM2.5 had the highest risk for AD, followed by dementia and Parkinson’s disease34. Fourth, the disease burden of AD and other dementias was estimated in the GBD study 2019. Thus, the limitations of the GBD database itself, such as the data quality from available countries and methodology, were also applicable to our study.

In conclusion, the current study supported that exposure to air pollution was associated with increased risks of the incidence, death, and DALY rate due to AD and other dementias. These associations of PM2.5 and ozone with death and DALY rate were substantially attenuated, suggesting that higher greenness modified the harmful effects of PM2.5 and ozone on disease burden of dementias. With accelerated industrialization and explosive urbanization, our findings might be important to public health implications toward increasing more green spaces to cope with the adverse effects of air pollution on human beings.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

International, A. D. World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes To Dementia. (London: Alzheimer’s Disease International (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2019).

Collaborators, G. B. D. D. F. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public. Health. 7, e105–e125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 (2022).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet 396, 413–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6 (2020).

Block, M. L. & Calderon-Garciduenas, L. Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci. 32, 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.009 (2009).

Yao, Y. et al. The effect of china’s clean air act on cognitive function in older adults: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 3, e98–e108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00004-6 (2022).

Ru, M., Brauer, M., Lamarque, J. F. & Shindell, D. Exploration of the Global Burden of Dementia Attributable to PM2.5: What Do We Know Based on Current Evidence? Geohealth 5, e (2020). GH000356 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GH000356 (2021).

Jin, X., Shu, C., Zeng, Y., Liang, L. & Ji, J. S. Interaction of greenness and polygenic risk score of alzheimer’s disease on risk of cognitive impairment. Sci. Total Environ. 796, 148767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148767 (2021).

Aitken, W. W. et al. Relationship of neighborhood greenness to alzheimer’s disease and Non-Alzheimer’s dementia among 249,405 U.S. Medicare beneficiaries. J. Alzheimers Dis. 81, 597–606. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-201179 (2021).

Markevych, I. et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Res. 158, 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.028 (2017).

Murray, C. J. L. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

Hammer, M. S. et al. Global estimates and Long-Term trends of fine particulate matter concentrations (1998–2018). Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7879–7890. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c01764 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Exposure to ambient air pollution and the incidence of dementia: A population-based cohort study. Environ. Int. 108, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.08.020 (2017).

Parra, K. L., Alexander, G. E., Raichlen, D. A., Klimentidis, Y. C. & Furlong, M. A. Exposure to air pollution and risk of incident dementia in the UK biobank. Environ. Res. 209, 112895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.112895 (2022).

Zhao, N. et al. Long-term Ozone exposure and mortality from neurological diseases in Canada. Environ. Int. 157, 106817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106817 (2021).

Shi, L. et al. A National cohort study (2000–2018) of long-term air pollution exposure and incident dementia in older adults in the united States. Nat. Commun. 12, 6754. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27049-2 (2021).

Astell-Burt, T., Navakatikyan, M. A. & Feng, X. Urban green space, tree canopy and 11-year risk of dementia in a cohort of 109,688 Australians. Environ. Int. 145, 106102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106102 (2020).

Rodriguez-Loureiro, L. et al. Long-term exposure to residential greenness and neurodegenerative disease mortality among older adults: a 13-year follow-up cohort study. Environ. Health. 21, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00863-x (2022).

Klompmaker, J. O. et al. Surrounding green, air pollution, traffic noise exposure and non-accidental and cause-specific mortality. Environ. Int. 134, 105341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105341 (2020).

Zagnoli, F. et al. Is greenness associated with dementia?? A systematic review and Dose-Response Meta-analysis. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 9, 574–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-022-00365-5 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Fine particulate matter and poor cognitive function among Chinese older adults: evidence from a Community-Based, 12-Year prospective cohort study. Environ. Health Perspect. 128, 67013. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP5304 (2020).

Maji, S., Ghosh, S. & Ahmed, S. Association of air quality with respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity rate in delhi, India. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 28, 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2018.1487045 (2018).

Shou, Y. et al. A review of the possible associations between ambient PM2.5 exposures and the development of alzheimer’s disease. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 174, 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.086 (2019).

Moulton, P. V. & Yang, W. Air pollution, oxidative stress, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Environ. Public. Health. 2012 (472751). https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/472751 (2012).

Martinez-Lazcano, J. C. et al. The effects of Ozone exposure and associated injury mechanisms on the central nervous system. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2012-0084 (2013).

Block, M. L., Zecca, L. & Hong, J. S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: Uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2038 (2007).

Crouse, D. L. et al. Complex relationships between greenness, air pollution, and mortality in a population-based Canadian cohort. Environ. Int. 128, 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.047 (2019).

Yuchi, W., Sbihi, H., Davies, H., Tamburic, L. & Brauer, M. Road proximity, air pollution, noise, green space and neurologic disease incidence: a population-based cohort study. Environ. Health. 19, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-0565-4 (2020).

Chen, L., Liu, C., Zhang, L., Zou, R. & Zhang, Z. Variation in tree species ability to capture and retain airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 3206 (2017).

Moura, B. B., Bolsoni, V. P., de Paula, M. D., Dias, G. M. & de Souza, S. R. Ozone impact on emission of biogenic volatile organic compounds in three tropical tree species from the Atlantic forest remnants in Southeast Brazil. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 879039 (2022).

Fallmann, J., Forkel, R. & Emeis, S. Secondary effects of urban heat Island mitigation measures on air quality. Atmos. Environ. 125, 199–211 (2016).

Chen, L., Liu, C., Zou, R., Yang, M. & Zhang, Z. Experimental examination of effectiveness of vegetation as bio-filter of particulate matters in the urban environment. Environ. Pollut. 208, 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.09.006 (2016).

Gomez-Cabrera, M. C., Domenech, E. & Vina, J. Moderate exercise is an antioxidant: upregulation of antioxidant genes by training. Free Radic Biol. Med. 44, 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.001 (2008).

Ji, J. S., Zhu, A., Lv, Y. & Shi, X. Interaction between residential greenness and air pollution mortality: analysis of the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Lancet Planet. Health. 4, e107–e115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30027-9 (2020).

Fu, P., Guo, X., Cheung, F. M. H. & Yung, K. K. L. The association between PM2.5 exposure and neurological disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 655, 1240–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.218 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by PhD Research Foundation of the first Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu medical university.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenjia Peng: Conceptualization, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. Ting Liu: Data Curation, Software, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, W., Liu, T. Greenness modified the association of PM2.5 and ozone with global disease burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Sci Rep 15, 26823 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11552-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11552-3