Abstract

Promoting cooperation remains a major challenge in natural science. While most studies focus on single strategy update rules, individuals in real-life often use multiple strategies in response to dynamic environments. This paper introduces a mixed update rule combining imitation and reinforcement learning (RL). In imitation learning (IL), individuals adopt strategies from higher-payoff opponents, while RL relies on personal experience. Simulations of the Prisoner’s Dilemma Game (PDG), Coexistence Game (CG), and Coordination Game (CoG), both in well-mixed populations and square lattice networks, show that: (i) cooperation and defection coexist in the PDG, resolving the dilemma of universal defection; (ii) cooperation exceeds the mixed Nash equilibrium in the CG; and (iii) cooperators dominate in the CoG. The mixed update rule outperforms single strategy approaches in those games, highlighting its effectiveness in fostering cooperation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cooperation is a widespread phenomenon observed in both nature and human society, encompassing levels ranging from molecular interactions to complex biological systems. However, Darwin’s theory of evolution, which emphasizes survival of the fittest and individual interest maximization, does not adequately account for the prevalence of cooperation. Although cooperative behavior enhances collective benefits, it often conflicts with individual self-interest, creating a social dilemma of cooperation1. Consequently, understanding the mechanisms by which cooperation emerges and persists among rational, self-interested individuals has become a fundamental question in game theory research2.

Evolutionary game theory3,4,5 serves as a powerful framework for quantitatively analyzing cooperative behavior. Within this field, five evolutionary mechanisms-kin selection6,7,8, direct reciprocity9,10, indirect reciprocity11, group selection12,13, and network reciprocity14,15,16,17 have been identified as pivotal contributors. Among these, punishment18,19,20, social exclusion21 and reputation22,23,24,25,26 have garnered significant attention due to its promising results in studies conducted on square lattice networks. In essence, the evolution of cooperation is ultimately studied from the perspective of strategy updating.

Strategy updating, or learning mechanisms, is a crucial factor influencing cooperation in evolutionary game theory. Successful strategies are typically assumed to spread more rapidly27,28, characterized by higher reproduction rates or an increased likelihood of imitation. Various update rules have been proposed, including the Moran process29,30,31,32, pairwise comparison33, imitation34,35,36,37,38, aspiration-driven processes39,40,41,42,43,44, and RL45,46,47,48,49. The imitation mechanism promotes the spread of successful strategies through payoff comparisons, while the aspiration-driven mechanism39 adjusts strategies based on the gap between actual payoffs and predetermined expectations. In contrast, RL45 relies on individuals’ historical experiences and corresponding payoffs to guide current strategy choices. This diversity of update rules provides a foundation for further exploration of cooperative behavior under combined mechanisms.

While most studies have focused on the emergence and maintenance of cooperation under a single update rule, heterogeneous strategy update rules are prevalent in nature. For example, ants combine IL and experiential learning when foraging for food50. In recent years, research on heterogeneous update rules has garnered increasing attention. For instance, the combination of imitation and aspiration-driven update rules has been used to study the evolution of cooperation51,52,53, and the integration of imitation with innovation-based update rules has also been explored54. These studies typically employ probabilistic models or group-specific mechanisms to investigate the interaction between different update rules51.

Inspired by previous studies, this paper proposes a mixed update mechanism that combines RL and IL. In this mechanism, RL guides decision-making based on an individual’s historical strategies and payoffs, while IL selects better strategies through payoff comparisons. Individuals adopt RL with probability \(\gamma\) and IL with probability \(1-\gamma\). When the two update rules lead to conflicting strategies, the final strategy is determined probabilistically, with \(\gamma\) for RL and \(1-\gamma\) for IL.

This study differs from52 in three key ways. First, it employs a mixed mechanism that combines RL and IL, rather than aspiration-driven and imitation-based update rules. Second, the results are consistent across both well-mixed populations and square lattice networks: RL promotes cooperation in the PDG and CGs but suppresses it in the CoG, while IL has the opposite effect, promoting cooperation in the CoG and suppressing it in the PDG and CGs. In contrast,52 reports opposite outcomes for these games in the two network structures. Third, under the mixed mechanism, cooperators dominate the population in the CoG, whereas cooperators and defectors coexist in52. These contributions provide a novel perspective and methodology for studying the evolution of cooperation.

Additionally, this study differs significantly from54 in two key aspects. First, the mixed learning (ML) update mechanism in this paper combines IL and RL, whereas54 explores a mechanism that integrates IL with innovation-based update processes. Second, in this study, agents select the RL update rule with probability \(\gamma\) (\(\gamma \in [0,1]\)) and the IL update rule with probability \(1-\gamma\). In contrast,54 assumes that a subset of agents adopts the imitation update rule, while the remaining agents follow the innovation update rule.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the game model. In Section 3, the strategy update rules are described and convergence analyses are provided. Simulation experiments are presented for a well-mixed population in Section 4 and for a square lattice network in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study.

The game models

This section provides a detailed introduction to two models: well-mixed populations and square lattice networks. In both models, agents have two alternative strategies: cooperation (C) and defection (D). In each round, each agent receives a payoff based on a symmetric payoff matrix, defined as follows:

A cooperator receives a reward, \(a_{11}\), when paired with another cooperator, but a sucker’s payoff, \(a_{12}\), when paired with a defector. A defector, on the other hand, receives a temptation payoff, \(a_{21}\), when paired with a cooperator, and a punishment payoff, \(a_{22}\), when paired with another defector.

This paper considers PDG \((a_{21}>a_{11}>a_{22}>a_{12})\), CG \((a_{21}>a_{11}\), \(a_{12}>a_{22})\) and CoG \((a_{11}>a_{21}\), \(a_{22}>a_{12})\).

Well-mixed populations

In a well-mixed population, agents do not have fixed neighbors, and any agent may interact with any other. See Fig. 5a. For a well-mixed population of size N, at round t, the population state is denoted as \(x(t) = (x_C(t), x_D(t))\), where \(x_C(t)\) (respectively, \(x_D(t)\)) represents the number of agents choosing strategy C (respectively, D), such that \(x_C(t) + x_D(t) = N\). The expected payoffs for agents choosing strategies C and D can be obtained using the following Eq.56,57:

Structured populations

This paper examines the structure of a square lattice network, where nodes represent agents and edges define the relationships between neighboring agents. Once the network is generated, the neighbors of all agents are fixed, and each agent can interact only with its neighbors. Agents located in the interior have four neighbors, while those on the boundary have either three or two neighbors, as shown in Fig. 5b. For agent \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\), at round t, the average payoff is defined as follows:

where \(y^i_C(t)\) (respectively, \(y^i_D(t))\) denotes the proportion of the neighbors for agent i choosing strategy C (respectively, strategy D) at round t. It clearly holds that \(y^i_C(t)+y^i_D(t)=1\).

Theoretical analyses of updating rules

IL update rule

Social learning theory, proposed by Fudenberg and Levine58, is a form of IL in which only certain agents actively learn from those with higher payoffs. The social learning update rule is described as follows: if all agents have the same payoff, no changes occur; otherwise, part of agents with lower payoffs will imitate those with higher payoffs, while the rest will remain unchanged59.

Let \(\alpha\) be the fraction of active learning agents among those with the same payoff. Then the population state is updated as follows:

where

and \(u_C(x(t))\) (respectively, \(u_D(x(t)))\) is the expected payoff of agents choosing strategy C (respectively, strategy D).

Take PDG, CG and CoG as examples to analyze the convergence under the IL update rule.

-

(I)

PDG

It follows from Eqs. (1) and (2) that \(u_D(x(t))-u_C(x(t))=\frac{(a_{21}-a_{11})x_C(t)+(a_{22}-a_{12})x_D(t)+a_{11}-a_{22}}{N-1}\). Since \(a_{21}>a_{11}>a_{22}>a_{12}\), then \(u_C(x(t))<u_D(x(t))\) holds for all x(t). By Eq. (4), then \(q_1(x(t))=q_2(x(t))=0\) and \(x_C(t+1)=(1-\alpha )x_C(t)\). If \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), then \(\lim _{t \rightarrow \infty } x_C(t) \rightarrow 0\), which is the Nash equilibrium of this game.

-

(II)

CG

By Eqs. (1) and (2), when \(x_C(t)=\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), \(u_C(x(t))=u_D(x(t))\) is obtained. According to Eq. (4), then \(q_1(x(t))=1\), \(q_2(x(t))=0\) and \(x_C(t+1)=x_C(t)\), i.e., the population state has remained the same. The result of convergence is the mixed strategy Nash equilibrium \((\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}},\frac{(N-1)a_{11}-N a_{21}+a_{22}}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}})\).

Since \(a_{21}>a_{11}\) and \(a_{12}>a_{22}\), when \(x_C(t)>\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), \(u_C(x(t))<u_D(x(t))\) is obtained. It follows from Eq. (4) that \(q_1(x(t))=q_2(x(t))=0\) and \(x_C(t+1)=(1-\alpha )x_C(t)\). If \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), as time goes on, \(x_C(t)\) is gradually decreasing, and when it decreases to \(\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), it follows from the first case that \(x_C(t)\) will remain constant. That is, the result of convergence is the mixed strategy Nash equilibrium \((\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}},\frac{(N-1)a_{11}-N a_{21}+a_{22}}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}})\).

When \(x_C(t)<\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), \(u_C(x(t))>u_D(x(t))\) is obtained. By Eq. (4), \(q_1(x(t))=q_2(x(t))=1\) and \(x_C(t+1)=x_C(t)+\alpha x_D(t)\). When \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), as time goes on, \(x_C(t)\) is gradually increasing, and when it increases to \(\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), it follows from the first case that \(x_C(t)\) will remain constant. That is, the result of convergence is the mixed strategy Nash equilibrium \((\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}},\frac{(N-1)a_{11}-N a_{21}+a_{22}}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}})\).

To conclude, when \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), \(\lim _{t \rightarrow \infty } x_C(t) \rightarrow \frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), i.e., the result of convergence is the mixed strategy Nash equilibrium \((\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}},\frac{(N-1)a_{11}-N a_{21}+a_{22}}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}})\) regardless of the initial population state.

-

(III)

CoG

By Eqs. (1) and (2), when \(x_C(t)=\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), \(u_C(x(t))=u_D(x(t))\) is obtained. According to Eq. (4), then \(q_1(x(t))=1\), \(q_2(x(t))=0\) and \(x_C(t+1)=x_C(t)\), i.e., the population state has remained unchanged. The result of convergence is the mixed strategy Nash equilibrium \((\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}},\frac{(N-1)a_{11}-N a_{21}+a_{22}}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}})\).

Due to \(a_{11}>a_{21}\) and \(a_{22}>a_{12}\), when \(x_C(t)>\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), \(u_C(x(t))>u_D(x(t))\) is obtained. It follows from Eq. (4) that \(q_1(x(t))=q_2(x(t))=1\) and \(x_C(t+1)=x_C(t)+\alpha x_D(t)\). When \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), \(\lim _{t \rightarrow \infty } x_C(t) \rightarrow N\), i.e., the result of convergence is the pure strategy Nash equilibrium (N, 0), where all agents choose to cooperate.

When \(x_C(t)<\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), \(u_C(x(t))<u_D(x(t))\) is obtained. By Eq. (4), \(q_1(x(t))=q_2(x(t))=0\) and \(x_C(t+1)=(1-\alpha )x_C(t)\). When \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), \(\lim _{t \rightarrow \infty } x_C(t) \rightarrow 0\), i.e., the result of convergence is the pure strategy Nash equilibrium (0, N), where all agents choose to betray.

In summary, when \(x_C(t)=\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), then the population state remains unchanged. When \(x_C(t)>\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), the population converges to the pure strategy Nash equilibrium (N, 0), where all agents choose to cooperate. When \(x_C(t)<\frac{a_{11}-a_{22}+N(a_{22}-a_{12})}{a_{11}+a_{22}-a_{12}-a_{21}}\), the result of convergence is the pure strategy Nash equilibrium (0, N), where all agents choose to betray.

RL update rule

RL is independent of the strategic environment and can be interpreted as a form of self-learning. In 1997, Camerer and Ho55 proposed a general model known as experience-weighted attraction (EWA) learning. In this model, agents update the preferences of all strategies, with the strategy having a higher preference being more likely to be selected. The preference of strategy \(a \in \{C, D\}\) for agent i is defined as follows:

In this model, \(F_i^a(t)\) represents the preference of agent i for strategy a after round t; \(\phi\) denotes the discount factor; \(\delta\) is the weighting coefficient for the assumed payoff obtained from the unselected strategy; \(f_i^a(t)\) represents the payoff of agent i when selecting strategy a in round t. If a denotes the cooperative strategy, then \(f_i^a(t) = a_{11}\) or \(a_{12}\); if a denotes the defection strategy, then \(f_i^a(t) = a_{21}\) or \(a_{22}\); \(H(t) = \rho H(t-1) + 1\) represents the number of ‘observation-equivalents’ of past experiences before round t; \(\rho\) is the depreciation rate or retrospective discount factor, which measures the impact of past experiences relative to the new period; H(0) is the value assigned before the game, and \(F_i^a(0)\) represents agent i’s initial preference for strategy a at the start of the game.

By Eq. (5), the probability of choosing strategy a (\(a \in \{C,D\}\)) is defined as follows:

where \(\lambda ^k ~ (k \in \{C,D\})\) represents sensitivity to strategy k.

For all experiments analyzed in this paper, the payoff matrices for the PDG, CG and CoG are \(\begin{bmatrix} -1 & -10 \\ 0 & -8 \end{bmatrix}\), \(\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 0 \\ 4 & -1 \end{bmatrix}\) and \(\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 0 \\ 0 & 2 \end{bmatrix}\).

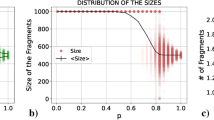

To verify the convergence of those games under the RL update rule, different initial population states \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\), depreciation rates \(\rho\), parameters \(\delta\) and decay rates \(\phi\) are considered. We set parameters \(N=1000\), \(H(0)=3\), \(maxgen=300\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\) and \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\). When \(\delta =\rho =0.5\), the \(\phi\) vs \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\) phase plane for the mean fraction of cooperators (denoted briefly by MFC) are shown in Figs. 1a, 2a and 3a. In addition, cooperative traits in \(\delta -\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\) parameter panel with \(\phi =\rho =0.5\) are depicted in Figs. 1b, 2b and 3b. The \(\rho\) vs \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\) phase plane for MFC with \(\phi =\delta =0.5\) are visualized in Figs. 1c, 2c and 3c.

-

(I)

PDG

From Fig. 1b,c, as \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) increase, so does the MFC, namely, high values of \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) are more effective at promoting cooperation. However, the MFC decreases instead as \(\phi\) increases from Fig. 1a, i.e., lower value of \(\phi\) is more effective at promoting cooperation.

-

(II)

CG para From Fig. 2a, the MFC decreases instead as \(\phi\) increases, i.e., lower value of \(\phi\) is more effective at promoting cooperation. However, from Fig. 2b,c, as \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) increase, the MFC also increases, namely, large values of \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) are more effective at promoting cooperation.

-

(III)

CoG

From Fig. 3b,c, the MFC decreases instead as \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) increase, i.e., lower values of \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) are more effective at promoting cooperation. However, as \(\phi\) increases, so does the MFC from Fig. 3a, that is, large value of \(\phi\) is more effective at promoting cooperation.

Heat maps concerning MFC (colors) for the PDG (\(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=-8\)) with different combinations of \(\phi\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\), \(\delta\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\), \(\rho\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\). Panel (a) is performed with \(\delta =\rho =0.5\). Panel (b) illustrates MFC as a function of \((\delta ,\frac{x_C(0)}{N})\) under \(\phi =\rho =0.5\). Panel (c) depicts MFC as a function of \((\rho ,\frac{x_C(0)}{N})\) under \(\phi =\delta =0.5\). It shows that high values of \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) but lower value of \(\phi\) are more effective at promoting cooperation.

Heat maps concerning MFC (colors) for the CG (\(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\), \(a_{22}=-1\)) with different values of \(\phi\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\), \(\delta\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\), \(\rho\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\). Panel (a) \(\phi -\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\) parameter panel with \(\delta =\rho =0.5\). Panel (b) is performed with \(\phi =\rho =0.5\). Panel (c) cooperative traits in \(\rho -\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\) parameter panel with \(\phi =\delta =0.5\). It shows that high values of \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) but lower value of \(\phi\) are more effective at promoting cooperation.

Heat maps concerning MFC (colors) for the CoG (\(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=2\)) with different combinations of \(\phi\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\), \(\delta\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\), \(\rho\) and initial population state \(\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\). Panel (a) \(\phi -\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\) parameter panel with \(\delta =\rho =0.5\). Panel (b) illustrates MFC as a function of \((\delta ,\frac{x_C(0)}{N})\) under \(\phi =\rho =0.5\). Panel (c) cooperative traits in \(\rho -\frac{x_C(0)}{N}\) parameter panel with \(\phi =\delta =0.5\). It shows that high value of \(\phi\) but lower values of \(\delta\) and \(\rho\) are more effective at promoting cooperation.

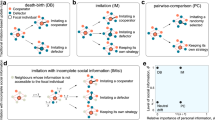

The ML update rule

Given that agents possess a certain degree of rationality, they exhibit both IL and RL abilities in each round of the game. Based on the IL update rule outlined in Section 3.1 and the RL update rule described in Section 3.2, this paper proposes a ML update rule. Specifically, agents select the RL update rule with probability \(\gamma\) (\(\gamma \in [0,1]\)) and the IL update rule with probability \(1-\gamma\). When the strategies updated through IL and RL are inconsistent, the strategy updated via RL is selected with probability \(\gamma\), and the strategy updated through IL is chosen with probability \(1-\gamma\). The parameter \(\gamma\) represents the tradeoff between IL and RL. When \(\gamma = 0\), agents rely solely on IL; when \(\gamma = 1\), they adopt only RL. For values of \(\gamma \in (0,1)\), agents must consider both update rules. To examine the impact of the ML update rule on cooperation evolution, three games-PDG, CG, and CoG-are analyzed in both well-mixed populations and square lattice networks. Diagrams illustrating the adoption of the proposed ML update rule in a well-mixed population and square lattice network are presented in Fig. 4a,b, respectively.

(a) Agents participate in a symmetric \(2 \times 2\) game within a finite, well-mixed population. Each agent selects the RL update rule with probability \(\gamma\) (\(\gamma \in [0,1]\)) and the IL update rule with probability \(1-\gamma\). In the left black box, the solid red circle represents a cooperator, while the solid green circle represents a defector. The agents’ neighbors are not fixed, and every agent in the population has the potential to interact with others. The learning update rules for the agents are shown in the right black box. (b) Agents engage in a symmetric \(2 \times 2\) game within a square lattice network. All agents are positioned at the vertices of the square lattice, and their neighbors are fixed. Each agent can only interact with their immediate neighbors. As in part (a), all agents choose the RL update rule with probability \(\gamma\) (\(\gamma \in [0,1]\)) and the IL update rule with probability \(1-\gamma\).

Based on the ML update rule proposed in this paper, the agent’s strategy update process is outlined as follows:

-

(a)

Initialize parameters, including the introspection rate \(\alpha\), discount factor \(\phi\), depreciation rate \(\rho\), the weighting coefficient for unselected strategies \(\delta\), the trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\), initial preferences \(F^C(0)\) and \(F^D(0)\), the initial experience value H(0), population size N, and the maximum number of iterations maxgen.

-

(b)

Initialize the population: each agent randomly selects a strategy from \(\{C,D\}\), i.e., each agent is randomly assigned a value of 0 (defection) or 1 (cooperation).

-

(c)

Determine the population state: the population state is obtained by calculating \(\sum _i s_i\) and \(N - \sum _i s_i\), where \(i \in \{1, \dots , N\}\) and \(s_i \in \{0,1\}\). This state is used in Eqs. (1) and (2).

-

(d)

Calculate average payoffs, pure payoffs, and probabilities: average payoffs are calculated under the IL update rule, while pure payoffs and probabilities are determined under the RL update rule. Expected payoffs of agents choosing strategies C and D are obtained from Eqs. (1) and (2) in a well-mixed population, and from Eq. (3) in a square lattice network. Pure payoffs are derived from the payoff matrix and opponents. Based on the preferences for strategies C and D, computed using Eq. (5), the probability of choosing strategy a (\(a \in \{C,D\}\)) is determined by Eq. (6).

-

(e)

Calculate pending strategies: the updated strategy of an agent is defined as pending strategy 1 under the RL update rule, and pending strategy 2 under the IL update rule. In a well-mixed population, the expected payoff of an agent choosing strategy C is compared with that of an agent choosing strategy D, and \(P_{max} = \max _{s \in {C,D}} u_s(x(t))\). The agent whose expected payoff is less than \(P_{max}\) is recorded, and we randomly select agents with a ratio of \(\alpha\) from those agents to adjust their strategies. In a square lattice network, based on the IL update rule, for each agent, if both the agent and all of their neighbors follow the same strategy, the agent remains unchanged. Otherwise, the agent’s average payoff is compared with those of neighbors who have a different strategy. If the agent’s average payoff is minimal, the agent may adjust their strategy. The agents likely to adjust their strategies are recorded, and we randomly select agents with a ratio of \(\alpha\) from those agents to adjust their strategies. Additionally, agent i selects strategy C (respectively, strategy D) with probability \(Pr_i^C\) (respectively, \(Pr_i^D\)) under the RL update rule in both the well-mixed population and the square lattice network.

-

(f)

Each agent compares their pending strategy 1 with pending strategy 2. If the strategies are unequal, the agent selects pending strategy 1 with probability \(\gamma\) and pending strategy 2 with probability \(1-\gamma\). If the strategies are equal, the agent selects pending strategy 1.

-

(g)

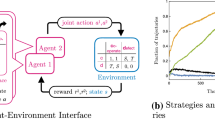

If the maximum number of iterations maxgen is reached, the process ends. Otherwise, return to step (c). See Fig. 2 for the flow chart of specific policy update.

Simulation experiment of well-mixed populations

Convergence analysis of the mixed update rule in a well-mixed population

This subsection focuses on the convergence of three games under the ML update rule in a well-mixed population. \(\phi\) is the discount factor, indicating the extent to which past experiences affect the present. In general, past experiences are instructive for the present. \(\delta\) is the weighting coefficient for the assumed payoff obtained from the unselected strategy. If a certain strategy has hardly been selected before, it indicates that the strategy is a poor one and the preference for it will also be relatively low. According to the analysis results in 3.2, when \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\) and \(\phi =0.8\), the proportion of cooperators in the three games is relatively high. We set parameters \(N=10000\), \(maxgen=100\), \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\), \(\gamma =0.5\), \(\alpha =0.3\), \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\), \(\phi =0.8\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\), \(H(0)=3\) and \(x_C(0)=x_D(0)=\frac{N}{2}\). Figure 6 shows the trend of the MFC of the three games in a well-mixed population with the iterative process.

The MFC varies with the iteration process for three games in a well-mixed population. The blue solid lines, red solid lines, and green solid lines correspond to the PDG (\(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=-8\)), CG (\(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\), \(a_{22}=-1\)), and CoG (\(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=2\)), respectively.

In the PDG, the MFC fluctuates around \(42\%\) as iterations progress under the ML update rule. Since the unique Nash equilibrium of the PDG is that defectors dominate the entire population, the ML update rule alleviates the dilemma to some extent, encouraging agents to cooperate at a proportion of approximately \(42\%\).

In the CG, the MFC fluctuates around \(35\%\) as iterations progress under the ML update rule. According to the convergence analysis of IL, regardless of the initial population state, the system will ultimately converge to the mixed Nash equilibrium state \((\frac{1}{3}, \frac{2}{3})\). Thus, the proportion of cooperators increases under the ML update rule.

In the CoG, the proportion of cooperators reaches 1 by the 20-th iteration and remains constant thereafter under the ML update rule. Based on the convergence analysis of IL, if \(x_C(0) > \frac{2N+1}{5}\), the system will converge to a state where all agents choose cooperation. Therefore, under the ML update rule, the convergence result is consistent with that of the IL update rule.

Sensitivity analysis of trade-off coefficient on MFC

This subsection focuses on the sensitivity analysis of trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\) for three games under the ML update rule. We set parameters \(N=10000\), \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\), \(\alpha =0.3\), \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\), \(\phi =0.8\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\), \(H(0)=3\) and \(x_C(0)=x_D(0)=\frac{N}{2}\).

The MFC varies with trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\) for three games as the iteration progresses in a well-mixed population: (a) in the PDG (\(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=-8\)) with \(maxgen=100\); (b) in the CG (\(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\), \(a_{22}=-1\)) with \(maxgen=50\); (c) in the CoG (\(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=2\)) with \(maxgen=100\). The blue solid lines, red solid lines, green solid lines and black solid lines show the proposed processes, with \(\gamma =0\), \(\gamma =0.3\), \(\gamma =0.7\) and \(\gamma =1\), respectively.

For the PDG, it can be seen from Fig. 7a that the MFC increases with the increase of \(\gamma\). When \(\gamma =0\), the MFC decreases to \(0\%\), and remains unchanged thereafter. When \(\gamma =1\), the MFC fluctuates around \(45\%\).

In the CG, as seen in Fig. 7b, as \(\gamma\) increases, so does the MFC. The MFC is around \(43\%\) when \(\gamma = 0.7\). The MFC fluctuates around \(57\%\) when \(\gamma = 1\).

In the CoG, as shown in Fig. 7c, it takes longer for cooperators to dominate the population as \(\gamma\) increases. Cooperators occupy the entire population by the 18-th iteration when \(\gamma = 0\), whereas they occupy the entire population by the 40-th iteration when \(\gamma = 1\).

Sensitivity analysis of introspection rate on MFC

This subsection focuses on the sensitivity analysis of introspection rate \(\alpha\) for three types of games under the ML update rule. We set parameters \(N=10000\), \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\), \(\gamma =0.5\), \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\), \(\phi =0.8\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\), \(H(0)=3\) and \(x_C(0)=x_D(0)=\frac{N}{2}\).

The MFC varies with introspection rate \(\alpha\) for three games as the iteration progresses in a well-mixed population: (a) in the PDG (\(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=-8\)) with \(maxgen=100\); (b) in the CG (\(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\), \(a_{22}=-1\)) with \(maxgen=50\); (c) in the CoG (\(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=2\)) with \(maxgen=100\). The blue solid lines, red solid lines, green solid lines and black solid lines show the proposed processes, with \(\alpha =0\), \(\alpha =0.3\), \(\alpha =0.7\) and \(\alpha =1\), respectively.

As shown in Fig. 8a, the MFC in the PDG decreases as the introspection rate \(\alpha\) increases. When \(\alpha = 0\), the MFC fluctuates around \(45\%\), whereas it fluctuates around \(40\%\) when \(\alpha = 1\).

In Fig. 8b, the MFC in the CG game decreases as the introspection rate \(\alpha\) increases. When \(\alpha = 0\), the MFC is around \(57\%\), whereas it fluctuates around \(35\%\) when \(\alpha = 0.3\).

In Fig. 8c, for the CoG, the time required for cooperators to dominate the entire population increases as \(\alpha\) decreases. When \(\alpha = 0\), cooperators occupy the entire population by the 70-th iteration, whereas at \(\alpha = 1\), they occupy the entire population by the 9-th iteration.

Figure 7 shows that the trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\) inhibits cooperation in the CoG but promotes cooperation in the PDG and CGs within a well-mixed population.

Figure 8 illustrates that the introspection rate \(\alpha\) promotes cooperation in the CoG but inhibits cooperation in the PDG and CGs within a well-mixed population.

Simulation experiment of square lattice network

To further substantiate the conclusions drawn in Section 5 and gain a more detailed understanding of this phenomenon at the microscopic level, snapshots of a square lattice in three games were analyzed (see Figs. 9, 10, and 12). First, a \(100 \times 100\) square network is constructed, where each node represents an agent and the edges between nodes represent neighbor relationships. Internal nodes have four neighbors, while boundary nodes have either two or three neighbors, as shown in Fig. 4b. Unlike well-mixed populations, each agent can only interact with its fixed neighbors. Under the IL update rule, the average payoff of each agent is calculated based on interactions with all of its neighbors, while the pure payoff is used under the RL update rule. All agents choose the RL update rule with probability \(\gamma\) (\(\gamma \in [0,1]\)) and the IL update rule with probability \(1 - \gamma\).

Convergence analysis of the ML rule in a square network

We set parameters \(N=10000\), \(maxgen=200\), \(\gamma =0.5\), \(\alpha =0.3\), \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\), \(\phi =0.8\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\), \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\) and \(H(0)=3\). The initial population state is given randomly.

Snapshots of the population states for three games in a \(100 \times 100\) square lattice network. From top to bottom, (a–c) represent the CoG with \(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=2\); (d–f) denote the CG with \(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\), \(a_{22}=-1\); (g–i) show the PDG with \(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=-8\). From left to right, (a, d, g) represent the population states of those games at 50-th iteration; (b, e, h) show the population states of those games at 100-th iteration; (c, f, i) denote the population states of those games at 150-th iteration. Cooperators are depicted in red and defectors in green.

Fig. 9 shows snapshots of the population states for three games under the ML update rule at the 50-th, 100-th and 150-th iteration, respectively. By Fig. 9a–c, the MFC of the CoG gradually increases as iterations proceed, eventually cooperators occupy the entire population. It follows from Fig. 9d–f that the MFC of the CG remains near \(40\%\), which improves the proportion of cooperators compared to mixed Nash equilibrium \((\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3})\). By Fig. 9g–i, the MFC of the PDG fluctuates around \(44\%\), which solves the dilemma all agents choosing to defect in the unique Nash equilibrium state.

Sensitivity analysis of trade-off coefficient on MFC

We set parameters \(N=10000\), \(maxgen=200\), \(\alpha =0.3\), \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\), \(\phi =0.8\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\), \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\) and \(H(0)=3\). The initial population state is given randomly.

Snapshots of the population states for three games in a \(100 \times 100\) square lattice network. From top to bottom, the first row denotes the CoG with \(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=2\); the second row shows the CG with \(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\), \(a_{22}=-1\); the third row denotes the PDG with \(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=-8\). From left to right, the first, second, third and fourth columns represent the population states of these games with \(\gamma =0\), \(\gamma =0.3\), \(\gamma =0.7\) and \(\gamma =1\), respectively. Cooperators are depicted in red and defectors in green.

The MFC varies with trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\) for three games as iterations proceed in a \(100 \times 100\) square lattice network: (a) CoG with \(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\) and \(a_{22}=2\); (b) CG with \(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\) and \(a_{22}=-1\); (c) PDG with \(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\) and \(a_{22}=-8\). The blue solid lines, red solid lines, green solid lines, and black solid lines show the proposed processes with \(\gamma =0\), \(\gamma =0.3\), \(\gamma =0.7\), and \(\gamma =1\), respectively.

Figures 10 and 11 show snapshots and the MFC of three games varies with trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\) as the iteration proceeds in a square lattice network, respectively. From Figs. 10a–d and 11a, it takes more time for cooperators to occupy the population as \(\gamma\) grows when \(\gamma <1\). When \(\gamma =1\), the proportion of cooperators gradually increases as iterations proceed, reaching \(80\%\) at the 200-th iteration. Therefore, lower value of \(\gamma\) is more effective at promoting cooperation in the CoG.

From Figs. 10e–h and 11b, if \(\gamma =1\), the MFC of the CG is the largest converging to \(58\%\). If \(\gamma =0\), the MFC of the game converges to \(36\%\). Therefore, higher value of \(\gamma\) is more effective at promoting cooperation in the CG.

It follows from Figs. 10i–l and 11c that higher value of \(\gamma\) is more effective at promoting cooperation in the PDG. The MFC of the PDG is around \(47\%\) when \(\gamma =1\). However, that of the game fluctuates around \(37\%\).

Sensitivity analysis of introspection rate on MFC

We set parameters \(N=10000\), \(maxgen=200\), \(\gamma =0.5\), \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\), \(\phi =0.8\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\), \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\) and \(H(0)=3\). The initial population state is given randomly.

Figures 12 and 13 show snapshots and the MFC of three games varies with introspection rate \(\alpha\) as the iteration proceeds in a square lattice network. From Figs. 12a–d and 13a, in the CoG, it takes less time for cooperators to occupy the population as \(\alpha\) increases when \(\alpha >0\). The proportion of cooperators gradually increases as the iteration progresses, reaching \(77\%\) when \(\alpha =0\). Therefore, high value of \(\alpha\) is more effective at promoting cooperation.

It follows from Figs. 12e–h and 13b that the MFC of the CG decreases as the increase of \(\alpha\). The MFC of the game fluctuates around \(58\%\) when \(\alpha =0\), while that of the game fluctuates around \(32\%\) when \(\alpha =1\).

Similarly, it follows from Figs. 12i–l and 13c that lower value of \(\alpha\) is more effective at promoting cooperation in the PDG.

Snapshots of the population states for three games in a \(100 \times 100\) square lattice network. From top to bottom, (a–d) denote the CoG with \(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=2\); (e–h) show the CG with \(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\), \(a_{22}=-1\); (i–l) represent the PDG with \(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\), \(a_{22}=-8\). From left to right, the population states of these games are represented with \(\alpha =0\), \(\alpha =0.3\), \(\alpha =0.7\) and \(\alpha =1\), respectively. Cooperators are depicted in red and defectors in green.

The MFC varies with introspection rate \(\alpha\) for three games as iterations proceed in a \(100 \times 100\) square lattice network: (a) CoG with \(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\) and \(a_{22}=2\); (b) CG with \(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\) and \(a_{22}=-1\); (c) PDG with \(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\) and \(a_{22}=-8\). The blue solid lines, red solid lines, green solid lines, and black solid lines show the proposed processes, with \(\alpha =0\), \(\alpha =0.3\), \(\alpha =0.7\), and \(\alpha =1\), respectively.

Sensitivity analyses of trade-off coefficient and introspection rate on MFC

We set parameters \(N=10000\), \(maxgen=200\), \(\delta =0.01\), \(\rho =0.01\), \(\phi =0.8\), \(\lambda ^C=\lambda ^D=1\), \(F_i^C(0)=F_i^D(0)=3\) for all \(i \in \{1, \cdots , N\}\) and \(H(0)=3\). The initial population state is given randomly.

The MFC versus trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\) in panel (a) and the MFC versus introspection rate \(\alpha\) in panel (b) for three games in a \(100 \times 100\) square lattice network. The blue hollow circles, magenta solid squares and black solid triangles represent CoG (\(a_{11}=3\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=0\) and \(a_{22}=2\)), PDG (\(a_{11}=-1\), \(a_{12}=-10\), \(a_{21}=0\) and \(a_{22}=-8\)), CG (\(a_{11}=2\), \(a_{12}=0\), \(a_{21}=4\) and \(a_{22}=-1\)).

From Figs. 10, 11 and 14a, trade-off coefficient \(\gamma\) inhibits cooperation for the CoG but promotes cooperation for the CG and PDG in a square lattice network.

From Figs. 12, 13 and 14b, introspection rate \(\alpha\) promotes cooperation for the CoG but inhibits cooperation for the CG and PDG in a square lattice network.

Conclusion

This paper examines the evolution of cooperation under a ML update mechanism, which combines IL and RL update rules, within the context of a finite homogeneous population. RL agents are independent of the strategic environment and make strategy choices based on a probability proportional to their preference size, while imitators compare their payoffs with those of their opponents and adopt the strategies of opponents with higher payoffs.

The results obtained from the mixed population are consistent with those observed in a square lattice. Simulation analyses under the ML mechanism, conducted in both a well-mixed population and a square lattice network, reveal the following key findings: In the PDG, a stable proportion of cooperators emerges, overcoming the dilemma where defectors dominate the population; in the CG, the proportion of cooperators increases compared to the mixed Nash equilibrium; and in the CoG, cooperators eventually occupy the entire population. Sensitivity analyses of the ML update rule’s parameters show that increasing the probability of choosing RL (\(\gamma\)) enhances the proportion of cooperators in the CG and PDG, while prolonging the time for cooperators to occupy the entire population in the CoG. Additionally, increasing the proportion of imitators (\(\alpha\)) decreases the proportion of cooperators in the PDG and CGs, but accelerates the time for cooperators to dominate the population in the CoG.

Furthermore, a sole RL update rule suppresses cooperation in the CoG compared to the ML update mechanism, while the opposite effect is observed in the PDG and CGs. In contrast, a sole IL update rule promotes cooperation in the CoG relative to the ML update mechanism, whereas the opposite effect occurs in the PDG and CGs.

In the future, the case of infinite populations can be considered. In addition, the factors like reputation and social exclusion can be take into account for payoffs or preferences of agents.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, S. Y., Liu, Y. P., Zhang, F. & Wang, R. W. Super-rational aspiration induced strategy updating promotes cooperation in the asymmetric prisoner’s dilemma game. Appl. Math. Comput. 403(5805), 126180 (2021).

Pennisi, E. How did cooperative behavior evolve?. Science 309, 93–93 (2005).

Amaral, M. A. et al. Evolutionary mixed games in structured populations: Cooperation and the benefits of heterogeneity. Phys. Rev. E 93(4), 042304 (2016).

Hofbauer, J. & Sigmund, K. Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamics (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Sandholm, W. H. Population Games and Evolutionary Dynamics (MIT Press, 2010).

Michod, R. E. The theory of kin selection. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 13(1), 23–55 (2003).

Foster, K. R., Wenseleers, T. & Ratnieks, F. L. W. Kin selection is the key to altruism. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21(2), 57–60 (2006).

Gardner, A. Kin selection. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition) 26–31 (2015).

Maskin, E., Fundenberg D. Evolution and cooperation in noisy repeated games. Am. Econ. Rev. 80(2), 274–279 (1990).

Pacheco, J. M., Traulsen, A., Ohtsuki, H. & Nowak, M. A. Repeated games and direct reciprocity under active linking. J. Theor. Biol. 250(4), 723–731 (2008).

Panchanathan, K. & Boyd, R. Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature 432(7016), 499–502 (2004).

Nowak, M. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 314(5805), 1560–1563 (2006).

Traulsen, A. & Nowak, M. A. Evolution of cooperation by multilevel selection. P. Natl. A. Sci. 103(29), 10952–10955 (2006).

Ohtsuki, H. & Nowak, M. A. The replicator equation on graphs. J. Theor. Biol. 243(1), 86–97 (2006).

Ohtsuki, H. & Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary stability on graphs. J. Theor. Biol. 251, 698–707 (2008).

Du, W. B., Cao, X. B., Hu, M. B. & Wang, W. X. Asymmetric cost in snowdrift game on scale-free networks. Europhys. Lett. 87(6), 60004 (2009).

Su, Q., McAvoy, A. & Plotkin, J. B. Strategy evolution on dynamic networks. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 763–776 (2023).

Gao, S. P., Du, J. M. & Liang, J. L. Evolution of cooperation under punishment. Phys. Rev. E 101, 062419 (2021).

Quan, J., Pu, Z. & Wang, X. Comparison of social exclusion and punishment in promoting cooperation: Who should play the leading role?. Chaos Solitons Fractals 151, 111229 (2021).

Pi, J. X., Yang, G. H. & Yang, H. Evolutionary dynamics of cooperation in N-person snowdrift games with peer punishment and individual disguise. Physica A 592, 126839 (2022).

Liu, L., Chen, X. J. & Perc, M. Evolutionary dynamics of cooperation in the public goods game with pool exclusion strategies. Nonlinear Dyn. 97, 749–766 (2019).

Pan, Q., Wang, L. & He, M. Social dilemma based on reputation and successive behavior. Appl. Math. Comput. 384, 125358 (2020).

Zhu, H. et al. Reputation-based adjustment of fitness promotes the cooperation under heterogeneous strategy updating rules. Phys. Lett. A 384(34), 126882 (2020).

Tang, W., Yang, H. & Wang, C. Reputation mechanisms and cooperative emergence in complex network games: Current status and prospects. EPL 149, 41001 (2025).

Tang, W. et al. Cooperative emergence of spatial public goods games with reputation discount accumulation. New J. Phys. 26, 013017 (2024).

Bi, Y. & Yang, H. Based on reputation consistent strategy times promotes cooperation in spatial prisoner’s dilemma game. Appl. Math. Comput. 444, 127818 (2023).

Santos, F. C. & Pacheco, J. M. Scale-free networks provide a unifying framework for the emergence of cooperation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 098104 (2005).

Stojkoski, V., Utkovski, Z., Basnarkov, L. & Kocarev, L. Cooperation dynamics of generalized reciprocity in state-based social dilemmas. Phys. Rev. E 97(5), 052305 (2018).

Moran, P. A. P. The Statistical Processes of Evolutionary Theory (Clarendon Press, 1962).

Nowak, M. A., Sasaki, A., Taylor, C. & Fudenberg, D. Emergence of cooperation and evolutionary stability in finite populations. Nature 428(6983), 646 (2004).

Altrock, P. M. & Traulsen, A. Deterministic evolutionary game dynamics in finite populations. Phys. Rev. E 80, 011909 (2009).

Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary Dynamics: Exploring the Equations of Life (Harvard University Press, 2006).

Traulsen, A., Pacheco, J. M. & Nowak, M. A. Pairwise comparison and selection temperature in evolutionary game dynamics. J. Theor. Biol. 246(3), 522–529 (2007).

Sigmund, K. The Calculus of Selfishness (Princeton University Press, 2010).

Traulsen, A., Claussen, J. C. & Hauert, C. Coevolutionary dynamics: From finite to infinite populations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95(23), 238701 (2005).

Traulsen, A., Nowak, M. A. & Pacheco, J. M. Stochastic Payoff Evaluation Increases the Temperature of Selection. J Theor Biol 244, 349–356 (2007).

Altrock, P. M. & Traulsen, A. Fixation times in evolutionary games under weak selection. New J. Phys. 11(1), 013012 (2009).

Szolnoki, A. & Chen, X. Gradual learning supports cooperation in spatial prisoner’s dilemma game. Chaos Soliton Fract. 130, 109447 (2020).

Du, J., Wu, B., Altrock, P. M. & Wang, L. Aspiration dynamics of multi-player games in finite populations. J. R. Soc. Interface 11(94), 20140077 (2014).

Du, J., Wu, B. & Wang, L. Aspiration dynamics in structured population acts as if in a well-mixed one. Sci. Rep.-UK 5, 8014 (2015).

Liu, X., He, M., Kang, Y. & Pan, Q. Aspiration promotes cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemma game with the imitation rule. Phys. Rev. E 94(1), 012124 (2016).

Matja, P., Zhen, W. & Marshall, J. A. R. Heterogeneous aspirations promote cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemma game. Plos One 5, 515117 (2010).

Platkowski, T. Enhanced cooperation in prisoner’s dilemma with aspiration. Appl. Math. Lett. 22(8), 1161–1165 (2009).

Lim, I. S. & Wittek, P. Satisfied-defect, unsatisfied-cooperate: A novel evolutionary dynamics of cooperation led by aspiration. Phys. Rev. E 98(6), 062113 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Levy noise promotes cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemma game with reinforcement learning. Nonlinear dynam. 2, 1–10 (2022).

Jia, N. & Ma, S. Evolution of cooperation in the snowdrift game among mobile players with random-pairing and reinforcement learning. Physica A 392(22), 5700–5710 (2013).

Zhang, S. P., Zhang, J. Q., Chen, L. & Liu, X. D. Oscillatory evolution of collective behavior in evolutionary games played with reinforcement learning. Nonlinear Dyn. 99, 3301–3312 (2020).

Jia, D., Li, T., Zhao, Y., Zhang, X. & Wang, Z. Empty nodes affect conditional cooperation under reinforcement learning. Appl. Math. Comput. 413(6398), 126658 (2022).

Deng, Y. & Zhang, J. Memory-based prisoner’s dilemma game with history optimal strategy learning promotes cooperation on interdependent networks. Appl. Math. Comput. 390, 125675 (2021).

Amaral, M. A., Wardil, L., Perc, M. & Silva, J. K. L. D. Stochastic win-stay-lose-shift strategy with dynamic aspirations in evolutionary social dilemmas. Phys. Rev. E 94(3–1), 032317 (2016).

Arefin, M. R. & Tanimoto, J. Evolution of cooperation in social dilemmas under the coexistence of aspiration and imitation mechanisms. Phys. Rev. E 102, 032120 (2020).

Wang, X., Gu, C., Zhao, J. & Quan, J. Evolutionary game dynamics of combining the imitation and aspiration-driven update rules. Phys. Rev. E 100(2–1), 022411 (2019).

Xu, K., Li, K., Cong, R. & Wang, L. Cooperation guided by the coexistence of imitation dynamics and aspiration dynamics in structured populations. Europhys. Lett. 117(4), 48002 (2017).

Amaral, M. A. & Javarone, M. A. Heterogeneous update mechanisms in evolutionary games: mixing innovative and imitative dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 97(4–1), 042305 (2018).

Camerer, C. & Ho, T. Experience-Weighted Attraction Learning in Games: A Unifying Approach. Working Papers (1997).

Imhof, L. A. & Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary game dynamics in a wright-fisher process. J. Math. Biol. 52(5), 667–681 (2006).

Ashcroft, P., Altrock, P. M. & Galla, T. Fixation in finite populations evolving in fluctuating environments. J. R. Soc. Interface 11(100), 20140663 (2014).

Fudenberg, D. & Levine, D. K. The Theory of Learning in Games (MIT Press, 1998).

Bjornerstedt, J. & Weibull, J.W. Nash equilibrium and evolution by imitation. Working Paper Series (1994).

Acknowledgements

This study received support from the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (ZK[2022] General 168), the National Science Foundation of China (Grant 11271098), Scientific Research Project Results of Guizhou Open University (Guizhou Vocational and Technical College) (Project Number: 2023YB26) and Scientific Research Projects for the Introduced Talents of Guizhou University (No. [2021]90).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Tang: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Guolin Wang: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Zhiyan Xing: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, W., Wang, G. & Xing, Z. Evolution of cooperation guided by the coexistence of imitation learning and reinforcement learning. Sci Rep 15, 26136 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11557-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11557-y