Abstract

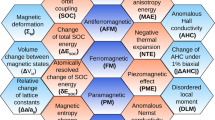

In this paper, an analytical model of a new bulk magnetostrictive actuator in three modes—longitudinal, bending, and torsional—are examined. The magnetostrictive material considered is a cylindrical vanadium permendur. This actuator is capable of operating in the mentioned modes both independently and in combination. Three constant magnetic fields are used to actuate the device in axial, bending, and torsional modes, and the calculation of each magnetostrictive coefficient dij is performed by considering all magnetic fields. The longitudinal deformation is applied through the Joule effect by stimulating the magnetostrictive material with a coaxial coil surrounding the material. The torsional mode is implemented via the Wiedeman effect by passing an electric current through a wire inside the magnetostrictive material. For the bending mode, the stimulation is achieved by applying a magnetic field on a surface of the material using a magnetic coupler. The actuator modeling is conducted using classical magnetostrictive equations, and the magnetostriction coefficients are modified for the excitation magnetic fields. Experimental tests are conducted to measure the coefficients. Ultimately, the magnetostrictive deformations in three modes are precisely refined and presented using nonlinear regression relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetostriction refers to the phenomenon in which ferromagnetic materials change their dimensions in response to a magnetic field1. These materials possess the unique capability of converting magnetic energy into mechanical energy, known as the Joule effect, and conversely, converting mechanical energy into magnetic energy, referred to as the Villari effect. The classical equations formulated to describe the behavior of magnetostrictive materials are linear and incorporate several simplifying assumptions. Consequently, these equations do not fully capture the complete behavior of magnetostrictive materials2. Karafi et al. developed a continuum electro-mechanical model for piezoelectric transducers to study their frequency response3. This model provides a comprehensive tool for designing, predicting, and optimizing transducers and energy harvesters. Linnemann et al. presented a comprehensive model for nonlinear behavior in magnetostrictive alloys and ferroelectric ceramics, particularly focusing on hysteresis effects4. The model is derived from a thermodynamically motivated uniaxial framework, incorporating a specific free energy function and a switching criterion. This approach ensures volume conservation for irreversible strains and can approximate ferromagnetic or ferroelectric hysteresis curves, including butterfly hysteresis. Additionally, it extends to ferrimagnetic behavior observed in magnetostrictive materials. Lin et al. introduced micromechanics formulations to analyze nonlinear piezomagnetism in magnetostrictive Terfenol-D composites under large magnetic fields5. It employed a simplified unit-cell method and reformulated Mori–Tanaka model to investigate composite behavior. Nonlinear magneto-elastic constitutive laws were linearized, followed by a homogenization process to minimize errors. Different composites, including fiber, particle, and lamina reinforcements, were studied, demonstrating good agreement with experimental data. These findings offered insights for sensor and actuator applications. Li et al. delved into the nonlinear piezomagnetic effect of iron-cobalt alloy, focusing on its equations and applications6. Using ANSYS finite element simulation, the piezomagnetic coefficient’s response to varying magnetic fields and stress levels was analyzed. Mathematical models based on electromagnetic theory were developed, revealing insights into sensor performance. Zhou et al. presented an analytical model to predict the magnetoelectric coefficient of laminated composites under pre-stress and magnetic bias loadings7. Using the equivalent circuit method and nonlinear magnetostrictive constitutive relations, the model accurately captured nonlinear magnetoelectric coupling effects. It highlighted the significant influence of pre-stress on the magnetoelectric coefficient, offering insights for optimizing device performance without requiring high magnetic bias fields. Zhou et al. presented an analysis of the dynamic magneto-mechanical response in magnetization-graded ferromagnetic materials (MGFM) used in magnetoelectric laminates8. A theoretical model for the piezomagnetic coefficient dependency on the bias magnetic field of MGFM was proposed, integrating nonlinear constitutive models and simulation software. The theoretical predictions aligned well with experimental results, enabling qualitative understanding of self-biased piezomagnetic response in MGFM and aiding in the design of magnetoelectric devices. Alexander developed a comprehensive mathematical model for magnetostrictive linear displacement transducers (MTD), utilizing COMSOL Multiphysics software9. The model integrates multiple physical phenomena including mechanical stress in the waveguide, electrical currents through the magnetostrictive material, and magnetic fields from permanent magnets and excitation currents. The paper highlights the model’s accuracy in reflecting real-world processes, with experimental data matching the model’s predictions within a 5% error margin. This model is noted for its completeness, integrity, and user-friendly visual control, marking a significant improvement over existing models in the design and development of magnetostrictive sensors. G.B. Nkamgang developed a model for analyzing the nonlinear dynamics of magnetostrictive hysteresis in thin rod actuators10. The study uses the method of multiple scales and Routh-Hurwitz theorem for stability and bifurcation analysis. Ashraf Saleem developed a model identification approach for Terfenol-D magnetostrictive actuators aimed at precise positioning control11. The study addresses the complexity of physical modeling for these actuators by employing a simpler empirical model. The results demonstrate that linear models can effectively capture the actuator’s behavior and are suitable for controller design. In last few years, new bending, torsional and hybrid longitudinal-torsional magnetostrictive actuators have been developed. Karafi presented a bulk magnetostrictive bending actuator using a permendur rod12. This actuator generates bending deformations by applying an axial magnetic field to a thin layer of the magnetostrictive rod. Magnetic fields are created with coils and a comb-shaped magnetic core. This bending actuator is ideal for applications requiring precise positioning, like TEM, STM, or AFM microscopes. Karafi et al. introduced a bulk magnetostrictive torsional transducer13. They introduced an innovative type of torsional transducer in which the magnetostrictive material served as the core and underwent torsional vibrations. By simultaneously applying an axial magnetic field and a circumferential magnetic field to a cylindrical magnetostrictive material, they utilized the Wiedeman effect to induce shear strain in the material. This actuator has been used to generate torsional displacements in a vibration assisted drilling process14. In 2013, Karafi et al. presented a longitudinal-torsional ultrasonic transducer employing a horn-shaped magnetostrictive material15. The transducer’s horn-shaped design was engineered to coincide the primary longitudinal and torsional modes at a frequency of 20,288 Hz. For analytical modeling of the transducers, they employed the piezomagnetic equations of magnetostrictive materials in the cylindrical coordinates. These equations were integrated with mechanical vibration equations to derive the general governing differential equation for the system, which they utilized for transducer design purposes. The horn exhibits longitudinal and torsional oscillations, influenced respectively by the Joule and Wiedeman effects. The stated configuration has been used to developed hybrid torsional- axial force magnetostrictive sensor16.

This study introduces an analytical model of a new bulk magnetostrictive actuator capable of operating in longitudinal, bending, and torsional modes simultaneously, using a cylindrical vanadium permendur alloy. The actuator is driven by applying constant magnetic fields in three orientations: volumetric axial, circumferential, and surface axial. Axial magnetic field is induced by a coaxial coil. Circumferential magnetic field is created by passing a wire through the cylinder, and the bending mode is activated by applying an axial magnetic field to the surface of the material using an attached magnetic coupler. To analyze the deformation of the actuator, piezomagnetic equations are employed. The primary aim is to develop a comprehensive model of the actuator using classical magnetostrictive equations and to accurately adjust the magnetostriction coefficients for the three modes. The study includes both modeling and experimental study, which allows for an in-depth investigation of the interactions between the combined modes and their impact on the actuator’s performance. The research aims to enhance the understanding of how multiple magnetic fields influence the behavior of magnetostrictive materials, providing a more detailed and accurate representation of their capabilities and limitations. This approach not only refines the theoretical models but also contributes to practical applications where precise control and prediction of the actuator behavior are important.

Principle of the actuator

The magnetostrictive material used in this study is 2V permendur, known for its isotropic magnetic characteristics. The design includes a centrally drilled hole along the axis of the magnetostrictive cylinder, through which a wire is passed. When an electric current is passed through the wire, it generates a circumferential magnetic field within the material. The bending mode is achieved by using a coupler fixed to the surface of the cylindrical magnetostrictive material, which induces an axial magnetic field on the material’s surface. This field leads to an asymmetric axial elongation in the vicinity of the coupler, causing the material to bend.

At ambient temperature, 2V permendur exhibits a saturation strain of around 60 ppm. Furthermore, it has a saturation magnetic flux density of 2.34 T and saturation magnetic field of approximately 20 kA/m. These properties make it suitable for applications requiring precise control of mechanical deformation through magnetic stimulation. The material’s isotropic nature ensures uniform magnetic response in all directions, enhancing the reliability and predictability of the actuator’s performance under various operating conditions.

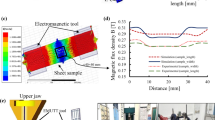

Figure 1 schematically shows how magnetic fields are applied to stimulate longitudinal, torsional, and bending modes.

The end of the rod is fixed to a base plate, effectively restricting its freedom of movement in all directions. A coaxial coil, consisting of a wire with a diameter of 1 mm and wound into 95 turns, is installed around the material. The coupler is chosen from CK45 due to its magnetic properties, with the goal of enhancing the induction of magnetic flux within it. To achieve this, 150 turns of wire are wound around the coupler and the coupler bonded to the material’s surface. Additionally, a wire is passed through the material to generate a circumferential magnetic field. A magnetic field of approximately 12,000 A/m, has the capability to saturate the material. In torsional mode, saturation of the magnetostrictive material is achieved with a current of around 30 A passing through the wire within the material. However, in bending mode, full saturation is not achieved due to the limited penetration of the magnetic fields into the material. The degree of bending increases with higher concentration of magnetic flux on the material’s surface. When magnetic fields are applied simultaneously in both bending and longitudinal modes, it is essential to ensure directions of the magnetic flux vectors. Misalignment may result in interference, omitting each other’s effects and preventing the material from achieving the desired bending or elongation. Figure 2 illustrates the configuration of a magnetostrictive actuator. In this arrangement, a coupler is used as the core of a bending coil to induce magnetic flux on the surface of the magnetostrictive material.

Although a variety of configurations have been developed for single-mode magnetostrictive actuators, integrating these configurations within the multi-mode actuator result in significant mutual interferences, which is taken into account in the design of the multi-mode actuator. The non-contact excitation systems minimize cross-mode coupling and reduce magnetic interferences.

Analytical model

Modeling magnetostrictive actuators presents a significant challenge due to the interplay of electrical, magnetic, and mechanical effects. This complexity largely stems from the nonlinear characteristics of these materials. The most widely used model for magnetostrictive materials is linear piezomagnetic equations.

In the given equation, T represents stress tensor, S represents strain tensor, H denotes the magnetic field intensity vector, and B is the magnetic flux density vector. The coefficient d, known as the magnetostriction coefficient (m/A) or the piezomagnetic constant, indicates the amount of strain per unit of magnetic field. Additionally, \({s}_{ij}^{H}\) is the compliance matrix tensor under a constant magnetic field (m2/N), and \({\mu }_{mk}^{T}\) is the magnetic permeability coefficient tensor at a constant stress.

This equation is primarily used for the linear modeling of magnetostrictive materials. Although the relationship between the magnetic field and mechanical strain in these materials is inherently nonlinear, linear coefficients can be used if the material’s deformations fluctuate minimally around a working point (bias point). Linear modeling can effectively describe small deformations caused by magnetic fields or stress, considering a constant magnetic bias or pre-stress. A constant magnetic bias is usually generated by a permanent magnet, which helps to reduce the nonlinearity of the materials. Under these conditions, the material’s behavior can be approximated as reversible and nearly linear.

When magnetostrictive materials are exposed to mechanical stress or a magnetic field, they undergo strain and magnetization changes. If the magnetostrictive material has reversible properties, this relationship can be described using mathematical equations. Equation 2 represents the matrix form of tensor Eq. 1.

In cylindrical coordinates, the values of S3 and S6 denote the longitudinal strain and the torsional strain of the magnetostrictive material, respectively. The equations for axial and torsional strain, disregarding mechanical stress (in a stress-free conditions), will be as follows:

In classical equations for magnetostrictive materials, the calculation of the magnetostriction coefficient dij is only dependent on the magnetic field in j direction, excluding other magnetic fields. For instance, when calculating d33, only the magnetic field in the z-direction is taken into account, along with the measurement of displacement in that direction. However, it’s important to note that the magnetic field in direction 2 can potentially influence this coefficient. This paper thoroughly examines the effects of magnetic fields of axial, torsional, and bending mode on the displacements of the magnetostrictive material, using a cylindrical coordinate system. Additionally, in this paper, the influence of the current in the bending coil on the actuator deformations is investigated both independently and considering other modes.

The first-order Taylor expansion approximation is used in the piezomagnetic equation. The condition for using finite Taylor series expansions is that it is written around a certain point.

However, the second-order Taylor expansion approximation is as follows:

According to Eq. 7, the relation between S3 and magnetic fields H1, H2, H3 is nonlinear. One way to make the nonlinearity into the account, is that consider it as nonlinear piezomagnetic coefficients as follows:

Dij are nonlinear piezomagnetic coefficients, which are functions of magnetic fields of Hi, Hj and Hk. The coefficients are obtained based on empirical tests in different conditions in this paper. Since in the muti-mode actuator, there is not the radial component of the magnetic field H1, therefore the analytical equation for longitudinal and torsional strains can be expressed as follows.

Experimental setup

Figure 3 shows the constructed magnetostrictive actuator. The magnetostrictive material is attached to a plate, with a hole drilled on the plate to permit a wire to pass through the material. The magnetostrictive material is wound with wire, forming a coil designed to stimulate the longitudinal mode. The coupler, selected for its desired magnetic properties and is bonded to the coaxial coil. Since the magnetostrictive material is excited in longitudinal, bending, and torsional modes, the coaxial coil is placed at a small distance from the material to avoid constraining its degrees of freedom. The magnetic permeability of the O-shaped core is greater than that of the magnetostrictive material. This ensures that the magnetic field passes through the surface layer of the magnetostrictive material.

Displacement measurements were performed using an Omron ZX-LD40 laser sensor, which has an analog output and a resolution of 2 microns. Three laser sensors were used to independently measure the three deformations. One sensor was placed above the magnetostrictive material to measure longitudinal displacement. To magnify amplitude and minimize noises, a mechanical arm is used to increase the scale of the measured bending and torsional deformations.

The analog outputs of the sensors are connected to a computer using an Advantech 1716 DAQ card. Data visualization and storage are managed by MATLAB Simulink software. The signal received in Simulink was filtered through an IIR low-pass filter and then amplified with a gain of 10,000 before storage. The filter was configured with a sample rate of 100 Hz, a passband frequency of 0.1 Hz, and a stopband frequency of 8 Hz.

Three independent power supply were used to excite the different modes of the actuator. Three ACS 712 5A current sensors were connected to the DAQ card to measure the real-time current applied to the coils. Data from both the current and laser sensors were simultaneously recorded. To eliminate noises from the data, a median filter was used.

When analyzing each mode independently, the corresponding current source and laser sensor for measuring the displacement of that mode are activated, and electric current and displacement are recorded simultaneously. Similarly, for investigating two or three modes concurrently, these steps are repeated.

Measurement of longitudinal strain as a function of axial magnetic field (d33)

To calculate the d33 coefficient, the value of longitudinal strain (S3) must be measured as a function of axial magnetic field (H3). For this purpose, the coaxial coil is excited to generate an axial magnetic field. The displacement of the magnetostrictive material is measured by a laser sensor installed along the axis of the material. Figure 4 illustrates the method for measuring the value of axial deformations.

The magnetic field inside the coil was determined as a function of the electric current using analytical equations and the Hall Effect sensor UGN 3503 with a sensitivity of 1.3 mV/G. Considering the sensitivity of the Hall effect sensor, its output represents the magnetic flux density. To calculate the magnetic field intensity, the magnetostrictive material was removed from the coil, and the Hall Effect sensor was placed inside the coil to measure the air magnetic flux density (Bair). The magnetic field intensity in the air can be calculated using Eq. 11.

where \({\mu }_{0}\) is the magnetic permeability of air. As the coil and the magnetostrictive material are parallel to each other, it can be inferred that the same value of Hair also passes through the magnetostrictive material. In this study, the empirical relationship between the current passing through the axial coil (I) and the magnetic field inside the coil (H3) was determined based on measured data. The results indicate that this relationship is linear and can be expressed as H3 = 822Ia.

Figure 5 displays the measured data of longitudinal strain as a function of axial magnetic field for the purpose of calculating the d33 coefficient.

The measured points on the graph were fitted using MATLAB’s Curve Fitting Toolbox to derive the equation describing the curve fitted on the points to calculate d33.

The d33 coefficient is derived from the slope of the \({S}_{3}-{H}_{3}\) curve.

Figure 6 illustrates the d33 coefficient of the magnetostrictive material.

Measurement of longitudinal strain as a function of circumferential magnetic field (d32)

To measure the d32 coefficient, the circumferential magnetic field (H2) must be applied to the magnetostrictive material, and its strain along the axis 3 should be measured. For this purpose, a wire is passed through the magnetostrictive material to generate a circumferential field in the rod. A strip is attached to the end of the rod, and a laser sensor measures the displacement of the end of the strip. Figure 7 schematically illustrates this test.

The electric current was passed through the wire in several steps ranging from 0 to 30 A. This electric current generated a circumferential magnetic field inside the magnetostrictive material. The laser sensor recorded the corresponding displacement for each electric current. In this test, the average value of the magnetic field was calculated using the following equations, where r1 represents the radius of the hole and r2 is the radius of the magnetostrictive material.

Figure 8 illustrates the data for measuring the longitudinal strain as a function of the circumferential magnetic field used to calculate the d32 coefficient.

The equation describing the curve passing through the experimental points was obtained using curve fitting as follows:

The d32 coefficient is the slope of the S3-H2 curve. By taking the derivative of Eq. 15, this coefficient is obtained as follows:

Figure 9 represents the d32 coefficient curve.

Measuring shear strain as a function of circumferential magnetic field (d62)

To measure the d62 coefficient, a circumferential magnetic field (H2) is applied to the magnetostrictive material, and the resulting torsional strain around its axis is measured. A wire passing through the material carries an electric current, generating a circumferential field in the rod. To amplify the torsion angle, a strip is attached to the end of the magnetostrictive material. Laser sensors and current measurement sensors simultaneously record the data. Figure 10 provides a schematic representation of this test.

Figure 11 illustrates the schematic and the equations used to determine S6. In this experiment, the magnetostrictive material’s length is 200 mm, the strip’s length is 200 mm, and R was set at 4.1 mm.

In this test, an electric current from 0 to 20 A was passed through the wire, generating a circumferential magnetic field within the magnetostrictive material. The average value of the circumferential magnetic field is considered. Figure 12 presents the measured torsional strain versus circumferential magnetic fields. The fitted equation from the test data is represented as a second-order polynomial. The fitted equation and the test graph are shown below.

The slope of the S6-H2 curve represents the d62 coefficient. By differentiating the Eq. 17, the d62 coefficient is obtained as follows.

Figure 13 shows the coefficient d62 as a function of circumferential magnetic fields.

The value of d31 and d61 are not measured, because the component of H1 (the radial magnetic field) is zero in this actuator. Also, the value of d63 is zero because the axial magnetic field has no effect on the torsional strain.

Measurement of longitudinal strain considering both axial and circumferential magnetic fields

As previously mentioned, in classical linear piezomagnetic equations, the dij coefficient is calculated by applying a magnetic field in the j direction and measuring the strain in the i direction, assuming other magnetic fields are zero. This assumption simplifies the equations and allows for linear consideration. In the performed test, the longitudinal strain of the magnetostrictive material was measured in the presence of both axial and circumferential magnetic fields. In this experiment, the electric current was applied to the axial coil and the wire passing through the material, and the longitudinal displacement is measured using the laser sensor. Figure 14 schematically illustrates the experimental setup.

The effects of both magnetic fields, denoted as H2 and H3, are significant on the coefficients d32 and d33. The following equation shows the correlation between the current passing through the axial coil and the current through the wire for measuring axial displacement, L3.

where Ia and It are axial coil and torsional wire currents. Figure 15 displays the plot of L3 against It and Ia. The two-dimensional plot on the horizontal plane represents the values of the axial coil current and the current passing through the wire, while the longitudinal displacement is shown on the vertical axis.

The above equation can be rewritten in terms of magnetic fields as follows. This equation represents the relationship between longitudinal strain S3 (ppm) as a function of axial and circumferential magnetic fields.

The nonlinear terms in equation are for accounting higher-order effects that become more significant at larger magnitudes of the excitation magnetic fields or currents. Figure 16 presents the experimental graph of S3 as a function of H2 and H3 , compared with the theoretical Eq. 9.

Measurement of torsional strain considering longitudinal and torsional magnetic field

In this experiment, electric currents are applied to the axial coil and the passing wire inside the material and the torsional strain was measured using the laser sensor. Figure 17 illustrates the experimental setup schematically.

The following equations illustrates the relationship between torsional strain in term of the current in the axial coil and the current passing through the wire. A strip with a length of 200 mm is attached to the material to amplify deformations.

Figure 18 presents the experimental graph of S6 as a function of H2 and H3, compared with the theoretical Eq. 10.

Measurement of magnetostriction deformations in combined modes

As mentioned, the magnetostrictive bending deformation not only depends on the magnetic field at the material’s surface but also on the axial and circumferential magnetic fields. In the presence of circumferential and axial fields, a portion of the material becomes saturated, reducing the contribution of the magnetic field to the magnetostrictive bending deformation. This argument holds for other modes as well.

To calculate the magnetostrictive bending deformation as a function of input parameters including axial coil current (Ia), bending coil current (Ib), and current passing through the wire (It), Eq. 24 is presented. In experiments conducted, the independent and combined effects of these three mentioned currents on magnetostrictive deformations were investigated. Three laser sensors were used to measure the displacement of the three modes separately. The electric current ranging from 0 to 10 A was passed through the coil wounded to the coupler, and the experiment was conducted in a quasi-static condition. The outputs of the three sensors and the value of the bending coil current were recorded. After removing noises and extracting the data, the data was discretely transferred to the Minitab software, where a nonlinear regression fit of the order 5 was performed. Equation 24 represents the value of the bending deflection as a function of the input electrical currents. The fitted equation, consisting of three nonlinear fifth-degree equations, enables the examination of the combined impact of all input parameters.

Additionally, the longitudinal displacement of the actuator can also be expressed as follows in terms of the three input currents.

As evident, the longitudinal strain not only depends on the longitudinal coil current but also on the bending current (Ib) and torsional current (It). These parameters have a significant influence on the longitudinal displacement, which is not accounted for in the classical equation mentioned. Equation 26 shows the torsional angle of the actuator.

The residuals for the three Eqs. (24), (25), and (26) were analyzed, with the R2 values for each mode calculated as follows: 89% for the longitudinal mode, 85% for the torsional mode, and 81% for the bending mode.

Conclusion

In this article, a new bulk magnetostrictive actuator was presented. The actuator is able to operate in longitudinal, torsional, and flexural modes independently and in combination. To excite the flexural mode, a coupler is employed to apply magnetic flux to the surface of the magnetostrictive material. Additionally, the torsional mode is induced by passing a wire through the magnetostrictive material and allowing an electric current to pass, following the Wiedeman effect. The longitudinal mode is also generated by a coaxial coil surrounding the magnetostrictive material. The displacement range of this actuator reaches up to 12 microns in the longitudinal mode, 7 microns in the flexural mode and 0.15 degrees torsionally. This article investigates the independent and combined effects of longitudinal, torsional, and flexural magnetic fields on the piezomagnetic coefficients. The coefficients presented in classical piezomagnetic equations are corrected and expanded, and the impact of all magnetic fields on each coefficient is measured and equations are derived accordingly. The corrected equations reveal that the influence of magnetic fields, not accounted for in classical equations, is significant. When precision is required, and multiple magnetic fields are applied to the material, the coefficients calculated from classical equations are inadequate and prone to error.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Engdahl, G. & Mayergoyz, I. D. Handbook of Giant Magnetostrictive Materials Vol. 107, 1–125 (Academic Press, San Diego, 2000).

Gopalakrishnan, S. Modeling of magnetostrictive materials and structures. In AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 1029(1), 140–157. (American Institute of Physics, 2008).

Karafi, M. & Kamali, S. A continuum electro-mechanical model of ultrasonic Langevin transducers to study its frequency response. Appl. Math. Model. 92, 44–62 (2021).

Linnemann, K., Klinkel, S. & Wagner, W. A constitutive model for magnetostrictive and piezoelectric materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 46(5), 1149–1166 (2009).

Lin, C. H. & Lin, Y. Z. Analysis of nonlinear piezomagnetism for magnetostrictive terfenol-D composites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 540, 168490 (2021).

Li, R. et al. Study on piezomagnetic effect of iron cobalt alloy and force sensor. Processes 10(6), 1218 (2022).

Zhou, H. M., Ou, X. W., Xiao, Y., Qu, S. X. & Wu, H. P. An analytical nonlinear magnetoelectric coupling model of laminated composites under combined pre-stress and magnetic bias loadings. Smart Mater. Struct. 22(3), 035018 (2013).

Zhou, H. et al. Analysis of magneto-mechanical response for magnetization-graded ferromagnetic material in magnetoelectric laminate. Materials 13(12), 2812 (2020).

Alexander, S., & Vasih, Y. Mathematical model of magnetostrictive linear displacement transducer. In 2019 International Conference on Electrotechnical Complexes and Systems (ICOECS), 1–4 (IEEE, 2019).

Nkamgang, G. B., Foagieng, E., Kamdoum, T. V., Talla, P. K. & Fomethe, A. A model for a thin magnetostrictive actuator in nonlinear dynamics. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 11, 1245–1256 (2015).

Saleem, A., Ghodsi, M., Mesbah, M., & Ozer, A. Model identification of terfenol-D magnetostrictive actuator for precise positioning control. In Active and Passive Smart Structures and Integrated Systems 2016, Vol. 9799, 702–709 (SPIE, 2016).

Karafi, M. R. & Nejabat, R. S. An introduction to a bulk magnetostrictive bending actuator using a permendur rod. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1–10 (2020).

Karafi, M. R., Hojjat, Y., Sassani, F. & Ghodsi, M. A novel magnetostrictive torsional resonant transducer. Sens. Actuators A 195, 71–78 (2013).

Karafi, M. R. & Korivand, S. Design and fabrication of a novel vibration-assisted drilling tool using a torsional magnetostrictive transducer. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 102, 2095–2106 (2019).

Karafi, M. R., Hojjat, Y. & Sassani, F. A new hybrid longitudinal–torsional magnetostrictive ultrasonic transducer. Smart Mater. Struct. 22(6), 065013 (2013).

Karafi, M. R. & Ehteshami, S. J. Introduction of a hybrid sensor to measure the torque and axial force using a magnetostrictive hollow rod. Sens. Actuators A 276, 91–102 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohammad Reza Karafi’s Contributions: Conceived the main idea of the hybrid actuator. Conducted and evaluated the analytical model. Supervised the project. Revised the manuscript. Saeed Ansari’s Contributions: Performed the experiments. Gathered and analyzed the data. Plotted the graphs. Prepared the draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansari, S., Karafi, M.R. Experimental characterization and modeling of a new bulk multi-mode magnetostrictive actuator. Sci Rep 15, 39567 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11582-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11582-x