Abstract

Nanomaterials with dual-functions integrating diagnostic and therapeutic abilities have attracted the interest in biomedical applications, and low-dimensional carbon dots have shown their potentialities in the field owing to their versatile optical and physicochemical properties. Yet the link between the surface emissive states and their structure and composition is not well understood, and their stability and biocompatibility needs to be further investigated. We have prepared a series of N- and O-doped carbon dots from a commercial commodity with a high surface functionalization, and performed a deep analysis to rationalize the structure-performance indicators that control their fluorescence, cytotoxicity and antioxidant properties. The synthesized carbon dots exhibited broad multiple surface emissive states: a bright blue emission at 430 nm governed by electronic transitions involving pyridones and carbonyl moieties, and a greenish emission at 500 nm due to transitions involving C-N and C-O groups or trap states. The carbon dots displayed good photostability with negligible photobleaching over continuous excitation during 2 h. The carbon dots also displayed good antioxidant activity correlated to the electron storage capacity of the aromatic core and O- and N- groups with proton exchange capacity. The carbon dots showed excellent cytotoxicity on human gingival fibroblast cell lines, and good response in in vitro fluorescence imaging over a wide concentrations range (0.05-1 mg/mL), similar to other contrast agents, demonstrating the potential of these N-O- doped carbon dots in imaging applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanomaterials with dual-function capabilities (integrating diagnostic and therapeutic features) have emerged as promising tools in biomedical applications; particularly in theranostics, where a single nanomaterial can be designed to enabling real-time imaging to monitor disease progression and simultaneously delivering treatments to target areas1,2. By integrating diagnostic capabilities like fluorescence imaging or magnetic resonance imaging with therapeutic actions such as drug delivery, photothermal therapy, or antioxidant effects, dual theranostic systems provide a more efficient and precise approach to disease management1,2,3. To achieve this, the nanomaterial must possess both fluorescence -for diagnostic imaging- and therapeutic properties such as antioxidant activity -to counteract oxidative stress in cells or tissues-. Furthermore, practical application for in vitro and in vivo imaging requires a precise control of the fluorescence (intensity, wavelength, stability) and photostability, both challenging issues for many organic fluorophores.

Low-dimensional carbon nanomaterials have gained significant interest in dual therapeutic and diagnostic applications due to their biocompatibility4,5,6,7,8, fluorescence (occasionally bright and wavelength tunable) and their capacity to act as oxidants (produce radicals and reactive oxygen species) or radical scavengers (antioxidants)9,10,11,12. Such duality is not observed in benchmark molecular antioxidants (e.g., vitamin C), and it is not intrinsic to all carbon nanomaterials but rather a complex function of their structure and composition11,12.

Despite the numerous studies describing the synthesis from a variety of precursors and synthetic routes of carbon nanomaterials and their potential for biomedical applications, yet their photostability and biocompatibility needs to be further investigated, and the mechanisms governing such performance are not sufficiently understood13,14,15,16. The optical properties of low-dimensional carbon nanomaterials depend on various factors such as the size, the structure of the core (amorphous, crystalline), or the surface functionalization (e.g., Csp2/Csp3 domains, nature of surface moieties)13,15,16,17,18. However, the mechanisms involved in those optical features (e.g., quantum confinement effects, surface states emission, molecular fluorophores, self-trapped exciton emission, solvent relaxation, aggregation centers.) remain rather uncertain, making it difficult to obtain materials with properties adapted to the intended application15,16. This complexity and the lack of a basic understanding of the composition-properties binomial represent an inherent limitation to push forward the biomedical applications of low-dimensional carbon nanomaterials.

Considering the above context, the goal of this study was to synthesize low-dimensional carbon nanomaterials with dual-function capabilities for diagnostic fluorescence imaging and antioxidant activity, and to perform a deep analysis to rationalize the composition-performance indicators that control their fluorescence, cytotoxicity and antioxidant properties. Based on our previous works on carbon nanodots with tunable emission and antitumoral activity in pre-clinical models19,20, we have used a commercial commodity precursor for the synthesis of N and O-doped carbon dots. We have evaluated the impact of the time of thermal processing of the precursor on the composition, fluorescence and antioxidant properties of the carbon nanodots. We have gained a deeper understanding of the nature of the surface moieties that control the fluorescence emission, cytotoxicity and antioxidant properties of the carbon dots (thus, paving the pathway towards the control and design of carbon dots with specific properties for a potential application as fluorescent imaging agents).

Results and discussion

Physicochemical characterization of the synthesized cds

The morphology and size of the synthesized CDs was investigated by scanning transmission electron microscopy; STEM, high resolution TEM images and the average distribution of particle sizes of selected samples are presented in Fig. 1. The images show a decrease in the average particle size of the carbon nanodots as the time of thermal processing of the precursor was raised, with (average) values ranging from 20 nm for sample CD-10 to 9 nm for sample CD-30. For the sample obtained after 40 min, two populations of particles with distinct average sizes were observed: the dominant population is composed of large aggregates with an average size of hundreds of nanometers and a pseudo-spherical morphology; the second population of nanoparticles showed an average size of ca. 7 nm (still following the decreasing trend with the synthesis time).

Clustering of carbon dot nanoparticles has been widely reported in the literature for functionalized carbon dots as those herein synthesized (see discussion below)21,22, and it is important since it may affect the fluorescence properties of the suspensions.

The freeze-dried powders obtained after the synthesis were initially characterized by thermogravimetry to analyze their thermal stability. Data is compared to that of the NHF precursor for comparison purposes (Fig. 2). A different thermal fingerprint was observed for the precursor and the CD samples, confirming the thermochemical transformation of the precursor. The profile of N-hydroxyphthalimide shows a sharp decomposition peak at around 235 ºC accounting for 38% of the overall mass loss, and a gradual mass loss featuring several humps between 300–600ºC until almost complete degradation (final solid yield was ca. 6 wt%). The CD samples displayed higher solid yields, following an increasing trend with the time of the thermal processing during the synthesis (i.e., 2, 7, 19, 23 wt% for 10, 20, 30 and 40 min, respectively). The mass loss in the region 120–400 ºC in the CD samples is associated to the decomposition of the carbonaceous matrix decorated with different functional groups.

The derivative of the thermal profiles clearly shows the differences among the CD and the precursor (inset Fig. 2a). The main peak indicative of the major mass loss in the CD samples is shifted to lower temperatures than for NHF (ca. 235 ºC), following a decreasing trend with the time of the thermal processing (i.e., 214, 199, 189, 170 ºC for CD-10, CD-20, CD-30 and CD-40, respectively). These thermal profiles point out to strong differences in the composition of the carbon dots compared to the NHF precursor, most likely attributed to a high surface oxidation during the synthesis (this will be discussed below). Similar thermal profiles have been reported for carbon dots obtained at moderate temperatures using other precursors21,23,24. It should be noted that the profile of sample CD-10 shows a mass loss between 220 and 250 ºC that overlaps partially with the main mass loss of NHF and its partial degradation intermediates (phthalic acid and phthalimide, Figure S1), suggesting that 10 min may be too short to assure the complete decomposition of precursor. This was not observed for the CDs obtained at longer processing times. A similar observation was obtained from Raman spectroscopy, where the profiles of the samples prepared at 10 and 20 min are ill-defined, and the spectra present some sharp peaks corresponding to the unreacted precursor (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the bands D and G bands characteristic of carbon materials start to be defined in samples CD-30 and CD-40, prepared at longer times.

This was further confirmed by the analysis of the surface composition by XPS (Table 1). As seen, all the samples displayed rather similar carbon contents of around 73 at% and high oxygen contents ranging from 21 to 24 at% indicating a high surface oxidation of the prepared materials (which is expected since the thermal decomposition of the precursor took place under air atmosphere). On the other hand, the nitrogen content slightly increased with the processing time, ranging from 3.3 at% for sample CD-10 to 5.0 at% for sample CD-40.

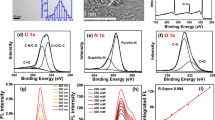

The differences in the surface functionalization of the samples were further investigated by the deconvolution of the high resolution XPS spectra of the carbon, oxygen and nitrogen core energy levels (Table 1; Fig. 3). The full deconvolution of the XPS spectra of the samples and the survey spectra are shown in Figure S2 and S3. The high-resolution spectra of C1s core energy level show multiple components corresponding to carbon atoms in varied chemical environments (see assignments in Table 1).

All the obtained CDs are predominantly constituted by carbon atoms in sp2 configuration (peak at 284.6 eV), with a second major fraction corresponding to carbon atoms in sp3 configuration representing aliphatic chains and/or defects. The fraction of Csp2 increased with the synthesis time (as opposed to the Csp3 fraction), pointing out a gradual aromatization of the core of the CDs as the temperature increased (and attributed to dehydrogenation reactions of the precursor)25,26. This was further confirmed by the somewhat increasing trend with the synthesis time of the relative abundance of the peak at 291 eV attributed to the π-π* shake up of aromatic carbon atoms27. On the other hand, the peak assigned to carbon bound to nitrogen in imine structures (285.4 eV) remained rather stable, which is consistent with the general trend of the overall nitrogen content.

The deconvolution of the peaks of the O1s core energy level indicates a gradual increase in the C = O bonds (e.g., carboxyl, carbonyl or amidic groups) with the synthesis time, in agreement with an increased surface oxidation. This is attributed to oxidative C-O coupling and dehydration reactions during the thermal decomposition of N-hydroxyphthalimide26.

The high-resolution N1s spectra were deconvoluted into three main components assigned to nitrogen in imine structures (398.7 eV), pyrrolic/pyridonic moieties (400.1 eV) and quaternary/amine groups (401.2 eV). The relative abundance of pyrrolic/pyridonic groups increased with the synthesis time, indicating a rearrangement of the carbon matrix during the thermal decomposition of the precursor. The characteristic signal of oxidized nitrogen was not observed for any of the samples (despite the oxidizing atmosphere of the synthesis), confirming that the decomposition of NHF proceeded via a dehydroxylation reaction. The relatively high oxygen and nitrogen contents of the CDs, combined with the difference in the nature of the surface groups are expected to influence the fluorescence emission properties and the antioxidant activity of the CDs. This will be discussed in the upcoming sections.

Optical properties of the CDs

The optical properties of the dispersions of the CDs were investigated by UV-Vis absorption (Figure S4) and steady state fluorescence emission at various excitation wavelengths (Fig. 4). All the suspensions showed a similar behavior characterized by well-defined absorption peaks in the region of 250–400 nm (Figure S4), attributed to π-π* transitions involving aromatic carbon sp2 domains, and n–π* transitions involving defect states of oxygen and nitrogen containing functional groups13,17,28,29,30. The absorption peaks differed in the extinction coefficient, with the sample treated for 40 min displaying the stronger absorption.

The photoluminescence emission spectra of dispersions of the CDs in ethanol excited from 300 to 400 nm are shown in Fig. 4. Broad asymmetric emission peaks were observed for all the samples, which is characteristic of complex electronic configurations involving multiple pathways for radiative transitions31,32,33. Comparatively, the spanning range of the emission profiles was rather similar for all the samples and the position of the maximum emission (ca. 450 nm) and did not vary with the synthesis time (Figure S5). The fluorescence intensity decreased as the excitation wavelength deviated from the optimal value (i.e., 370 nm for all the samples). An excitation-dependent emission response was observed for samples CD-10 and CD-20 upon excitation between 300 and 360 nm; the effect was almost negligible for the samples prepared at 30 and 40 min. A similar behavior has been reported for other carbon dots and has been attributed to multiple surface emissive states arising from various surface groups15,34,35,36.

The Stokes shift calculated at the excitation wavelength of the maximum intensity (ca. 370 nm) was ca. 80 nm for all the samples. This value is larger than that commonly reported for organic fluorophores, but of the same order of magnitude reported for functionalized carbon dots35. Such large Stokes shifts are often associated to systems with large contributions of non-radiative relaxation from high energy levels37.

(A-D) Photoluminescence emission spectra of the synthesized materials at different excitation wavelengths (insets: wavelength of maximum emission vs. the excitation wavelength); (E) absolute photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) upon excitation between 370–400 nm; (F) evolution of the average fluorescence lifetime of the CDs with the synthesis time.

Samples CD-30 and CD-40 displayed multiple well-defined emission peaks when excited above 350 nm. Since the emission was recorded in the same solvent for all the samples, this behavior cannot be attributed to different solvent relaxation effects, but to intraband relaxation phenomena (likely due to the presence of various fluorophores contributing to the overall emission profiles). The intensity of the maximum emission was very low for the sample prepared at 10 min, and reached a maximum value for the sample prepared at 20 min with a gradual decreasing trend for longer times. A similar time dependence behavior has been reported for the synthesis of CDs from hydrothermal approaches15. We attribute the low emission of sample CD-10 to the incomplete transformation of the precursor under these conditions, as also inferred by the thermal analysis (Fig. 2).

The absolute photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) upon excitation between 370 and 400 nm varied between 2 and 8% for samples CD-30 and CD-40, and between 15 and 25% for sample CD-20 (Fig. 4E). These values are consistent with the typical values reported in the literature for carbon dots, usually in the range of 2–15% depending on the synthesis method, composition and precursor38. Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy was used to evaluate the lifetimes and decay behaviors of the fluorescent species upon excitation at 370 nm (maximum emission for all the samples). The time resolved emission decay traces of the CDs are shown in Figure S6. The decay curves were reproduced by fitting to a multiexponential function, with two fast decay components (ca. 0.5–2.5 ns) and one long time decay component of 4.5–6.6 ns. It is interesting to remark that the average lifetime decreased (faster emission decay traces) with increasing the time of the synthesis (Fig. 4f, Table S1), suggesting more efficient non-radiative decays or quenching mechanisms. The reduction in the fluorescence lifetime can be associated to the increased n − π∗ transitions brought about by the functionalization (i.e., presence of unpaired electrons in substituted carbon atoms)29.

To further investigate the nature of the emitting species, we performed a deconvolution of the emission spectra recorded upon excitation at 370 nm. The deconvolution was done in Origin, assuming that the entire emission spectra can be represented as sum of individual Gaussian functions31,39. An example of the deconvolution for sample CD-30 is shown in Fig. 5; deconvolutions of all the samples are shown in Figure S7. Several distinct emission bands were identified in all the samples, centered at ca. 410 nm, 430 nm, 460 nm and 500 nm with a tail spanning between 540 and 600 nm (Fig. 5). These emission bands show different trends with the time of the thermal processing (Fig. 5B). The contribution of the emission at 410 nm (band I in Fig. 5) was rather constant for all the samples, and according to literature it can be ascribed to surface defects caused by functionalization40. The contributions of the emission bands centered at 430 and 460 nm (II and III) increased with the time of the synthesis (Fig. 5B), as opposed to the emission centered at 500 nm (IV).

Figures 5C-E show the correlation between these emission bands and the various radiative deexcitation pathways associated to the O- and N- surface moieties present in the CDs (see complete correlations in Figure S8). The contribution of the bright blue emission centered at 430 nm followed an increasing trend with the relative abundance of carbon atoms in sp2 configuration, nitrogen atoms in pyrrolic/pyridonic groups and oxygen in carbonyl moieties. This agrees with the assignment of this emission to the radiative deactivation of exciton pairs on amide complexes and pyridonic groups14,15,18,28,41,42. The emission centered at 500 nm (band IV) showed an increasing correlation with the relative abundance of carbon atoms in sp3 configuration and O-C moieties, in agreement with its assignment to n-π∗ transitions involving C-N and C-O groups and inter-system crossing or trap states31,41,42,43.

According to literature, the emission of carbon dots can also be partially attributed to molecular fluorophores either dissolved in the solution or retained in the surface of the carbon dots. This is the case, for instance of 2-pyridone derivatives, citrazinic acid or 5-oxo-1,2,3,5-tetrahydroimidazo-[1,2-α]-pyridine-7-carboxylic acid (IPCA) when citric acid, ethylenediamine or L-cysteine are used as precursors13,14,28. In our case, the contribution of emission from molecular fluorophores arising from the partial decomposition of the precursor has been discarded, since controls carried out with NHF dissolved in ethanol, as well as solutions of phthalic acid and phthalimide (degradation intermediates of NHF) showed no or low emission features at the studied wavelengths (Figure S9). This is also consistent with the low emission intensity of sample CD-10, that presented some impurities from unreacted NHF as discussed above (as inferred from the thermal analysis).

Photostability

The photostability of samples CD-30 and CD-40 was assessed by monitoring the fluorescence emission intensity over continuous excitation at 370 nm during 2 h. Data in Fig. 6 shows that the dispersions of the carbon dots retained ca. 96 and 89% (respectively) of the initial emission intensity after the first hour of continuous UV irradiation. Comparatively, samples CD-40 showed a lower photostability as the emission intensity declined faster over time than for CD-30. The effect was more pronounced during the first hour of UV irradiation and stabilized gradually during the second hour of UV irradiation (where the decline represented only ca. 4%).

The intensity of the emission was recorded after a relaxation period in the dark following the first UV continuous irradiation, showing a stable signal in the dark (no recovery or further decline of the emission). Beyond these differences between the samples, it can be concluded that shows a good photostability -similar than that reported for carbon dot dispersions in the literature-44,45 to be used in bioimaging applications.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of the prepared CDs was evaluated from the DPPH• assay, a widely recognized method for assessing the ability of antioxidants to neutralize free radicals46. Figure 7 shows the UV-VIS spectra of the DPPH• solutions in the presence of increasing concentration of the dispersions of CDs prepared at the different synthesis times. The strong absorbance of DPPH• was reduced in the presence of the carbon dots, demonstrating their ability to act as free radical scavengers neutralizing DPPH• radicals. The quantification of the antioxidant capacity showed that the carbon dots displayed antioxidant activity at relatively low concentrations (e.g., 0.016 mg/mL), although the effect was modest (ca. 10% activity). As the dose of carbon dots increased, the antioxidant activity also improved significantly. Interestingly, the samples prepared at longer synthesis times displayed slightly higher antioxidant activities (Fig. 6). This agrees with the increased aromatization and the evolution of the O- and N-moieties with the synthesis time (Table 2). In this context, the antioxidant capacity of carbon nanomaterials has been attributed to various mechanisms involving sp2 carbon atoms (electron storage) and functional groups (mostly hydroxyls, thiols, amines) capable of donating H+ ions to DPPH• radicals to form stable H-DPPH complexes5,6,11,12,47. In our carbon dots, we attribute the antioxidant activity to the presence of carboxylic, hydroxyl and amine groups as evidenced in the XPS analysis (Table 1). Nitrogen-rich (pyrrol, pyridone) groups also contribute significantly to the antioxidant properties of the CDs5,48,49.

The IC50 values (i.e., concentration of an antioxidant required to inhibit 50% of the free radical activity) and antiradical power parameter (ARP, reciprocal of IC50) of the samples are compiled in Table 2, and compared with those reported for carbon dots and benchmark non-enzymatic antioxidants reported in the literature47,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. The IC50 values for the synthesized carbon dots decreased with increasing the synthesis time, indicating the stronger antioxidant activity for the latter. These values are of the same order of those reported for other carbon dots in the literature, although lower than those of antioxidant benchmarks as ascorbic acid (vitamin C) (Table 2).

In vitro biocompatibility assessment over HGF cell lines

The cytotoxicity of the prepared carbon dots was evaluated by the in vitro biocompatibility assessment on human gingival fibroblast (HGF) cell lines. Figure 8 shows the viability of the cells incubated with varying concentrations of the samples ranging from 10 to 500 µg/mL for 24 h. These results of viability show that all the tested carbon dots demonstrated excellent biocompatibility across a wide range of concentrations, with a cell viability of 86% for the highest concentration assayed (ca. 500 µg/mL). For all the low concentrations the cell viability remained close to or above 90% (i.e., no harm to normal gingival fibroblast cells), further confirming the lack of cytotoxic effect of the prepared carbon dots. This confirms that they can be safely applied in biomedical applications (e.g., bioimaging, therapeutic interventions, antioxidant therapies) at the tested concentrations. Similar studies on cytotoxicity of carbon dots on HGF cell lines typically report viabilities above 90% for concentrations of carbon dots higher than those herein reported (e.g., below 0.1 mg/ml59), indicating the larger range of biocompatibility of our materials. Cell viability over 90% in similar ranges of concentration are similar to those reported for benchmark dyes used in fluorescence imaging such as Indocyanine Green60, and 5-Aminolevulinic Acid61.

In-vitro optical imaging

Based on the bright luminescence of the prepared carbon dot suspensions in the visible region and their biocompatibility, in vitro optical imaging of phantoms containing increasing concentrations of carbon dots was explored using Spectral Ami HT fluorescence. Images depicting the observed luminescence signal from four different concentrations of the suspensions are shown in Fig. 9, compared to those of the control (distilled water). All the CDs tested presented fluorescence under exaction at 320 nm, with red color indicating bright emission of the samples. The corresponding controls show a very low fluorescence.

The fluorescence intensity followed a linear dependence with the concentration of CDs in the dispersions, with higher slopes for the sample prepared at 20 min (CD-20) and slightly lower values for those obtained at longer synthesis times. The values of the slope from concentration ranges between 0.05 and 1 mg/mL (e.g., 2.9, 7.4, 4.3 and 5.8 for CD-10, CD-20, CD-30 and CD-40, respectively) are of the same other of those reported for other contrast imaging agents such as doped silica nanoparticles62 and chitosan-polypyrrole nanocomposites63. These results demonstrate the great potential of the prepared carbon dots as contrast agents in imaging applications.

Conclusions

In this study we have prepared a series of N- and O-functionalized carbon dots from the thermochemical conversion at ambient atmosphere of an organic chemical commodity (N-hydroxyphthalimide). We have investigated the impact of the time of thermal processing of the precursor (between 10 and 40 min) on the composition, fluorescence features and antioxidant properties of the obtained carbon dots. Data has shown that the prepared low-dimensional carbon dots showed dual-function capabilities for diagnostic fluorescence imaging and antioxidant activity. We have analyzed the composition-performance indicators that control the fluorescence, cytotoxicity and antioxidant activity to clarify the role of the surface moieties of the carbon dots.

Analysis of the surface composition showed a gradual aromatization of the core of the CDs as the temperature increased (opposed trend for Csp3) accompanied by an increased surface oxidation mainly in the form of C = O bonds (carboxyl, carbonyl, amidic) and pyrrolic/pyridonic groups. The control of the oxygen and nitrogen surface groups is critical to modulate the fluorescence emission properties and the antioxidant activity of the CDs. A deep analysis of the fluorescence data confirmed that the emissive features of the prepared carbon dots arises from the surface functionalization, with no contribution form molecular fluorophores. The broad emission bands are attributed to various radiative deexcitation pathways associated to the O- and N- surface moieties of the carbon dots. The bright blue emission at 430 nm was correlated to the presence of N-rich groups (amides, pyridones) and oxygen in carbonyl moieties. The emission at 500 nm (less intense) was correlated to transitions involving C-N and C-O groups and inter-system crossing or trap states. The good photostability of the CDs under continuous excitation conditions was demonstrated, which is an essential parameter in biological applications as it reduces the risk of photobleaching during extended cell imaging experiments. The CDs showed antioxidant activity at relatively low concentrations with IC50 values in the same order of those reported of carbon dots and benchmark non-enzymatic antioxidants. The antioxidant activity of the samples is correlated with the aromaticity of the core of the carbon dots (electron storage mechanisms involving sp2 carbon atoms) and the presence of O- and N- surface groups (carboxylic acids, hydroxyls, amines) capable of donating H+ to DPPH• radicals. The excellent biocompatibility (inferred from the in vitro cytotoxicity assays on human gingival fibroblast cell lines) and the good response in in vitro fluorescence imaging across a wide range of concentrations confirms that the prepared carbon dots can be safely applied in biomedical applications.

Methods

Synthesis of the carbon dots

The synthesis of the carbon dots from N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHF, Sigma Aldrich 97%) has been described elsewhere20. In a typical synthesis, about 5 g of NHF were introduced in a 50 mL open quartz tube reactor provided with a glass heating jacket. The precursor was heated under atmospheric conditions using a temperature/flow regulated hot air gun. The temperature was raised at 10 °C/min up to the melting point of NHF (ca. 233 °C); after the complete melting of the precursor, the temperature was raised to 280ºC and maintained for 10–40 min. Afterwards, the solid remaining in the quartz tube was flooded in 50 mL of cold ethanol, allowed to reach room temperature and further sonicated for about 10 min. The resulting dispersion was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 min and at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. The nearly transparent aqueous supernatants were collected and freeze-dried. The nomenclature of the samples was CD-t, where t is the time of the synthesis (e.g., CD-10, CD-20, CD-30 and CD-40).

Characterization techniques

X-ray photoelectronic spectroscopy (XPS) experiments were collected in a KRATOS Axis Nova instrument using monochromatic AlKα radiation and applying 20 mA and 15 kV. The spectra of dried samples were recorded with an incident X-ray beam focus on 0.7 × 0.3 mm area. The high-resolution spectra were collected using pass energy of 20 eV and a step size of 0.1 eV. ESCApe software was used for the processing of the XPS spectra, with energy values referenced to the C1s peak of adventitious carbon located at 284.6 eV, and a Shirley-type background. The morphology and average diameter size of the prepared materials was explored by Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) in a Verios G4 UC instrument (Thermo Scientific) functioning in STEM Mode at 25 kV, with a STEM 3 + detector. The samples were prepared by depositing the diluted sample on 400 Mesh carbon-coated copper grids and air-dried for 24 h in dust-free conditions at ambient temperature. High resolution TEM images were recorded in a HITACHI HT7700 device operated at 100 kV. The images were processed with ImageJ 1.48r software64. Thermogravimetric analyses of the samples were carried out in a thermobalance (Netzsch-STA 409 CD) using ca. 10 mg of sample under argon atmosphere and heating up to 1000 ºC (heating rate 10 ºC/min). Steady-state fluorescence of ethanolic dispersions of the samples was measured in a FluoroMax-4 spectrophotometer (Horiba) at excitation between 300 and 400 nm, using 10 mm path length quartz cuvettes. The excitation and emission slits were set at 2 nm. Absolute quantum yields (PLQY) and excited states lifetimes were recorded on Horiba Fluoromax 4P provided with a Quanta-φ integration sphere and a FluoroHub Time-Correlated Single-Photon Counting lifetime module using a 370 nm LED excitation source. Experimental lifetime decays were fitted to a single or multi-exponential decay model (see further details in the Supplementary Information). Photostability measurements were recorded with a 370 nm exaction light over two hours, with a relaxation period of 60 min between both exposures. Aqueous dispersions of the samples were irradiated and the maximum emission intensity was recorded at 5 s intervals. Raman spectra were recorded in a Renishaw InVia Qontor spectrometer using a 514 nm laser. The spectra were collected under a Leica DM2500 optical microscope with a x50 long working distance objective (ca. 10 mm). Each spectrum was recorded with an integration time of 5 s; data represents the average of three measurements.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of the samples was evaluated from their ability to scavenge 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl stable radical (DPPH•), following the procedure described elsewhere44. Briefly, stock solutions of DPPH• (0.05 mg/mL) and dispersions of the carbon dots at varied concentrations between 0 and 4 mg/mL were prepared in ethanol (90%). Two mL of the carbon dot suspensions were mixed with 2 mL of DPPH• stock solution in a lockable glass vial at room temperature. After 120 min of stirring, the unreacted DPPH• amounts were monitored by UV absorbance of the solutions between 250 and 700 nm in a Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer. All determinations were carried out in triplicate at room temperature and using 1 cm length path quartz cuvettes. A control sample was recorded using ethanol. All samples were protected from light until spectral analysis. The free radical scavenging activity of the samples was calculated as the inhibition degree according to: Inhibition = (Ac-As)/Ac x 100, where Ac and As are the absorbance at 517 nm of the control and carbon dots dispersions, respectively. The antioxidant activity was also expressed in terms of the IC50, defined as the amount of antioxidant required to reduce the concentration of DPPH radical by half, determined from the inhibition/concentration curves. The antiradical power parameter (ARP) was also calculated as the reciprocal value of IC50 (1/IC50).

Cell viability

Human gingival fibroblasts (HGF, CLS Cell Lines Service GmbH, Eppelheim, Germany) were cultured in alpha-MEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (both from PAN-Biotech GmbH) and 1% Penicillin‐Streptomycin‐Amphotericin B mixture (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Biocompatibility of NHF-CDs was assessed using the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were seeded into 96-well tissue culture-treated plates (50000 cells/mL) and, the next day, cells were incubated with NHF-CDs (10, 50, 100, 500 µg/mL) or fresh complete medium (control) for 24 h. Absorbance readings at 490 nm were performed using a FLUOstar® Omega microplate reader (BMG LABTECH). All experiments were carried out in triplicate (average data and error bar are presented), and the viability of treated cells was expressed relative to the viability of control cells.

In-vitro optical imaging

In vitro optical imaging was recorded in a SPECTRAL Ami HT instrument piloted by Aura imaging software. The experiment involved phantoms containing increasing concentrations of the carbon dots suspensions (ca. 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 mg/mL) and distilled water as control. The imaging procedure included excitation at 430 nm and emission at 530 nm. Other parameters were set as follows: LED excitation power 35 and 50%; exposure time 1 s; FOV 25 × 17.5 cm; F-stop 2 and binning 2. About 1 mL of the suspensions was deposited in 5 mL glass vials (that do not exhibit fluorescence at our excitation and emission wavelengths). The quantification of the fluorescence was conducted drawing circular regions of interest that covered the whole image of each sample, with the results reported in radiance units. The slope of the correlation between the fluorescence and the suspensions concentration was calculated to estimate the potential application of the samples as a fluorescence imaging agents.

Data availability

Datasets of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Jani, P., Subramanian, S., Korde, A., Rathod, L. & Sawant, K. K. Theranostic nanocarriers in cancer: dual capabilities on a single platform, in: (eds Thangadurai, D., Sangeetha, J. & Prasad, R.) Functional Bionanomaterials: from Biomolecules To Nanoparticles, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 293 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41464-1_13 (2020).

Yasun, E. Theranostic cancer applications utilized by nanoparticles offering multimodal systems and future insights. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03397-4 (2020).

Karthikeyan, L., Sobhana, S., Yasothamani, V., Gowsalya, K. & Vivek, R. Multifunctional theranostic nanomedicines for cancer treatment: recent progress and challenges. Biomedical Eng. Adv. 5, 100082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bea.2023.100082 (2023).

Tang, N., Ding, Z., Zhang, J., Cai, Y. & Bao, X. Recent advances of antioxidant low-dimensional carbon materials for biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1121477 (2023).

Innocenzi, P. & Stagi, L. Carbon Dots as oxidant-antioxidant nanomaterials, Understanding the structure-properties relationship. Crit. Rev. Nanotoday. 50, 101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2023.101837 (2023).

Peng, Z. et al. Carbon dots: biomacromolecule interaction, bioimaging and nanomedicine. Coord. Chem. Rev. 343, 256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2017.06.001 (2017).

Sharma, V., Tiwari, P. & Mobin, S. M. Sustainable carbon-dots: recent advances in green carbon Dots for sensing and bioimaging. J. Mater. Chem. B. 5, 8904. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TB02484C (2017).

Sachdev, A., Matai, I. & Gopinath, P. Implications of surface passivation on physicochemical and bioimaging properties of carbon Dots. RSC Adv. 4, 20915 (2014).

Li, Q. & Shen, X. Xing carbon quantum Dots as ROS-generator and -scavenger: a comprehensive review. Dyes Pigm. 208, 110784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110784 (2023).

Velasco, L. F., Maurino, E., Laurenti, E. & Ania, C. O. Light-induced generation of radicals on semiconductor-free carbon photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. Gen. 453, 310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.12.033 (2013).

Chong, Y. et al. Crossover between anti- and pro-oxidant activities of graphene quantum Dots in the absence or presence of light. ACS Nano. 10 (8690). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b04061 (2016).

Christensen, I. L., Sun, Y. P. & Juzenas, P. Carbon Dots as antioxidants and prooxidants. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 7, 667. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbn.2011.1334 (2011).

Zhang, Q., Wang, R., Feng, B., Zhong, X. & Ostrikov, K. Photoluminescence mechanism of carbon dots: triggering high-color-purity red fluorescence emission through edge amino protonation Nat. Commun 12, 6856. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27071-4 (2021).

Langer, M., Zdražil, L., Medveď, M. & Otyepka, M. Communication of molecular fluorophores with other photoluminescence centres in carbon Dots. Nanoscale 15, 4022. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2nr05114a (2023).

Ehrat, F. et al. Tracking the source of carbon Dot photoluminescence: aromatic domains versus molecular. Fluorophores Nano Lett. 17, 7710. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03863 (2017).

Wu, X., Liang, W. & Cai, C. Photoluminescence mechanisms of carbon quantum Dots. Progress Chem. 33, 1059. https://doi.org/10.7536/PC200715 (2021).

Mintz, K. J. et al. R.M. Leblanc A deep investigation into the structure of carbon Dots carbon, 173 433 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2020.11.017

Fu, M. et al. Carbon dots: A unique fluorescent cocktail of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Nano Lett. 15, 6030. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02215 (2015).

Tiron, C. E. et al. NHF-derived carbon dots: prevalidation approach in breast cancer treatment. Sci. Rep. 10, 12662. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69670-z (2020).

Tiron, A. C. S. et al. Manganese-doped N-hydroxyphthalimide-derived carbon dots—theranostics applications in experimental breast cancer models. Pharmaceutics 13, 1982 (2021).

Gonzalez-Vera, A. S. et al. Influence of the sequential purification of biomass-derived carbon Dots on their colloidal and optical properties. Carbon Trends. 19, 100460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cartre.2025.100460 (2025).

Ullal, N., Mehta, R. & Sunil, D. Separation and purification of fluorescent carbon dots – an unmet challenge. Analyst 149, 1680. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3AN02134C (2024).

Date, P. et al. Carbon dots-incorporated pH-responsive agarose-PVA hydrogel nanocomposites for the controlled release of Norfloxacin drug. Polym. Bull. 77, 5323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-019-03015-3 (2020).

Pandey, S., Mewada, A., Thakur, M., Tank, A. & Sharon, M. Cysteamine hydrochloride protected carbon Dots as a vehicle for efficient release of Anti-Schizophrenic drug haloperidol. RSC Adv. 3, 26290. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3RA42139B (2013).

Bauer, L. & Miarka, S. V. The chemistry of N-Hydroxyphthalimide. ACS Publications. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01565a061 (2002).

Krylov, I. B. et al. Electron-deficient N-oxyl radicals – new reagents for selective oxidative functionalization of organic substrate. J. Phys. : Conf. Ser. 1942, 012007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1942/1/012007 (2021).

Wagner, C. D. Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: A Reference Book of Standard Data for Use in X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, Perkin-Elmer (1979).

Ren, J. et al. Controlling the emission colour and chemical structure of carbon Dots by catalysis-tuned conversion of ortho-aminophenol. Carbon 231, 119706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2024.119706.( (2025).

Zhang, T. et al. A novel mechanism for red emission carbon dots: hydrogen bond dominated molecular States emission. Nanoscale 9, 13042. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr03570e (2017).

Li, H. J. et al. Deng amide (n, π∗) transitions enabled clusteroluminescence in solid-state carbon Dots adv. Funct. Mater. 33, Article 2302862, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202302862 (2023).

Olla, C. et al. Exploring the impact of nitrogen doping on the optical properties of carbon Dots synthesized from citric acid. Nanomaterials 13, 1344. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13081344 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Nitrogen doped carbon dots: mechanism investigation and their application for label free CA125 analysis. J. Mater. Chem. B. 7, 3053. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TB00021F (2019).

Qureshi, Z. A., Dabash, H., Ponnamma, D. & Abbas, M. K. G. Carbon Dots as versatile nanomaterials in sensing and imaging: efficiency and beyond. Heliyon 10 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31634 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Water-soluble, nitrogen-doped fluorescent carbon Dots for highly sensitive and selective detection of Hg2 + in aqueous solution. RSC Adv. 5, 40393. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra04653j (2015).

Meisner, Q. J. et al. Excitation- dependent multiple fluorescence of a substituted 2-(2′-Hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole. J. Phys. Chem. A. 122, 9209. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.8b07988 (2018).

Mohandoss, S. et al. Excitation-dependent multiple luminescence emission of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon Dots for cysteine sensing, bioimaging, and photoluminescent ink applications. Microchem. J. 167, 106280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2021.106280 (2021).

Liu, X. Z., Xu, J. M. & Cole Molecular design of UV–vis absorption and emission properties in organic fluorophores: toward larger bathochromic shifts, enhanced molar extinction coefficients, and greater Stokes shifts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 16584. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp404170w (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. One-step microwave-assisted polyol synthesis of green luminescent carbon Dots as optical nanoprobes. Carbon 68, 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2013.10.086 (2014).

Samokhvalov, A. Trap emission by nanocrystalline anatase in visible range studied by conventional and synchronous luminescence spectroscopy: adsorption and desorption of water vapor. J. Lumin. 192, 388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2017.07.009 (2017).

Zhu, P., Tan, K., Chen, Q., Xiong, J. & Gao, L. Origins of efficient multiemission luminescence in carbon Dots. Chem. Mater. 31 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b00870 (2019). 10.

Kasprzyk, W. et al. Luminescence phenomena of carbon Dots derived from citric acid and urea – a molecular insight. Nanoscale 10, 13889. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8NR03602K (2018).

Li, H. et al. Water-Soluble fluorescent carbon quantum Dots and photocatalyst design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4430. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200906154 (2010).

Liu, Y. et al. X room temperature synthesis of pH-switchable polyaniline quantum Dots as a turn-on fluorescent probe for acidic biotarget labeling. Nanoscale 10, 6660 (2018).

Fiori, F. et al. Highly photostable carbon Dots from citric acid for bioimaging. Materials 15, 2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15072395 (2022).

Dua, S. et al. Stability of carbon quantum dots: a. Crit. Rev. RSC Adv. 13, 13845. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA07180K (2023).

Brand-Williams, W., Cuvelier, M. E. & Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 28, 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5 (1995).

Tsai, H-W. et al. Y.W. Green synthesis of gardenia seeds-based carbon Dots for bacterial imaging and antioxidant activity in aqueous and oil samples. RSC Adv. 13, 29283. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA06293G (2023).

MacLean, P. D., Chapman, E. E., Dobrowolski, S. L., Thompson, A. & Barclay, L. R. C. Pyrroles as antioxidants: solvent effects and the nature of the attacking radical on antioxidant activities and mechanisms of pyrroles, dipyrrinones, and bile pigments. J. Org. Chem. 73, 6623. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo8005073 (2008).

Shalaby, M. A., Fahim, A. M. & Rizk, S. A. Antioxidant activity of novel nitrogen scaffold with Docking investigation and correlation of DFT stimulation. RSC Adv. 13, 14580. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA02393A (2023).

Saravanan, A. et al. Heteroatom co-doping (N, NS, NB) on carbon Dots and their antibacterial and antioxidant properties. Surf. Interfaces. 46, 103857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2024.103857 (2024).

Liang, Y., Hou, D., Ni, Z., Cao, M. & Cai, L. Preparation, characterization of naringenin, β-cyclodextrin and carbon quantum Dot antioxidant nanocomposites. Food Chem. 375, 131646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131646 (2022).

Rodríguez-Varillas, S. et al. Biocompatibility and antioxidant capabilities of carbon Dots obtained from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Appl. Sci. 12. 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12020773 (2022).

Gedda, G. et al. Green synthesis of multi-functional carbon Dots from medicinal plant leaves for antimicrobial, antioxidant, and bioimaging applications. Sci. Rep. 13, 6371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33652-8 (2023).

Salari, S., Esmaeilzadeh Bahabadi, S., Samzadeh-Kermani, A. & Yosefzaei, F. In-vitro evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial potential of greensynthesized silver nanoparticles using Prosopis farcta fruit extract. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 18, 430 (2018). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31089378

Moteriya, P. & Chanda, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles formation from Caesalpinia pulcherrima stem metabolites and their broad spectrum biological activities. J. Genetic Eng. Biotechnol. 16, 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgeb.2017.12.003 (2018).

Yan, Y. et al. Structural and functional properties of two phenolic acid-chitosan derivatives and their application in the preservation of Saimaiti apricot fruit food sci. Technol 43 https://doi.org/10.1590/fst.106922 (2023).

Tejwan, T. et al. Synthesis of green carbon Dots as bioimaging agent and drug delivery system for enhanced antioxidant and antibacterial efficacy. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 139, 1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109317 (2022).

Yuan, S. et al. Poria cocos-derived carbon Dots for cellular imaging, free radical scavenging and pH sensing. Diam. Relat. Mater. 137, 110121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2023.110121 (2023).

Bhavikatti, S. K. et al. Green-synthesized carbon Dots from ginger: multifunctional agents against oral pathogens with biocompatibility in human gingival fibroblast cells. Curr. Plant. Biology. 40, 100392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpb.2024.100392 (2024).

Pourhajibagher, M., Gharesi, S., Chiniforush, N. & Bahador, A. The effect of indocyanine green antimicrobial photothermal/photodynamic therapy on the expression of BCL-2 and BAX messenger RNA levels in human gingival fibroblast cells Folia Medica 62 314 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3897/folmed.62.e48038

D’Antonio, D. L. et al. Effect of 5-Aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) in ALADENT gel formulation and photodynamic therapy (PDT) against human oral and pancreatic cancers. Biomedicines 131316. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12061316 (2024).

Son et al. Advancing fluorescence imaging: enhanced control of cyanine dye–doped silica nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnol. 22 347. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02638-7 (2024).

Doan, V. H. M., Van Nguyen, T., Mondal, S., Choi, J. & Oh, J. Thi Mai Thien Vo, Cao Duong Ly, Dinh Dat Vu, Gebremedhin Yonatan Ataklti1, Sumin Park, Fluorescence/photoacoustic imaging–guided nanomaterials for highly efficient cancer theragnostic agent, Scientific Reports 11, 15943 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95660-w

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 671. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089 (2012).

Acknowledgements

In memoriam Acad. Bogdan C. Simionescu (1948-2024). The authors are thankful for the financial support from the grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, project no. PNRR-III-C9-2022-I8-291, contract no. 760081/23.05.2023, within the National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A Coroaba: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft; M Ignat, OE Carp, C Stan, SI Filipiuc, A Canizares, N Simionescu, C. Uritu: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing; NL Marangoci, M. Pinteala: Project administration, Fund¬ing acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing; CO Ania: Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coroaba, A., Ignat, M., Carp, OE. et al. Antioxidant activity and in vitro fluorescence imaging application of N-, O- functionalized carbon dots. Sci Rep 15, 25834 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11676-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11676-6