Abstract

The use of sedentary bioindicators, such as trees, in environmental contamination monitoring is receiving increased focus. This study evaluates Theobroma cacao L. as a bioindicator for cadmium (Cd) contamination by quantifying hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) as an oxidative stress marker in cellular suspensions exposed to CdSO₄. Chronoamperometric measurements using platinum electrodes indicated Cd accumulation in T. cacao L. and revealed a corresponding increase in H₂O₂ production up to a threshold level, beyond which cell apoptosis occurred. These findings support the potential of T. cacao L. as a bioindicator of Cd pollution. Moreover, H₂O₂ quantification via chronoamperometry demonstrated a rapid and effective method for detecting Cd-induced oxidative stress in plant systems. Future research should explore field applications, evaluate alternative plant species, and assess long-term responses under real environmental conditions to optimize this approach for large-scale biomonitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental biomonitoring is a crucial tool for assessing contamination risks and their impact on ecosystems. Among the various biomonitoring strategies, sedentary bioindicators—organisms that accumulate and reflect environmental contaminants—are especially useful for evaluating pollution levels over time1. Plants in particular are widely used to monitor toxic metal contamination due to their ability to absorb and store hazardous elements from soil and water2,3.

Ecuador has a strong agricultural and economic interest in cultivating cacao, or Theobroma cacao L. The country’s fine aroma cacao is particularly highly valued in European markets for its distinct flavor and quality4,5. While bioindicators are often associated with organisms like lichens and mollusks, which passively reflect environmental contamination, certain plant species can actively serve as effective localized biomonitors of soil pollution. T. cacao L., known for its ability to bioaccumulate cadmium (Cd), offers valuable insights into toxic metal contamination in agricultural ecosystems. This is especially relevant in Ecuador, where Cd pollution stems from both natural and anthropogenic sources, including industrial discharges, vehicular emissions, and artisanal mining11. Unlike traditional bioindicators, which are widely distributed across different environments, T. cacao L. is cultivated in specific agricultural regions, making it a particularly relevant indicator of pollution in economically important crops. Monitoring oxidative stress responses in cacao plants can provide an early warning of Cd exposure, facilitating the evaluation of soil contamination levels and potential risks to food safety. This localized approach to biomonitoring is crucial in regions where toxic metal accumulation threatens both agricultural productivity and compliance with international trade regulations.

Cadmium exposure severely affects plant morphology, causing stunted growth, chlorosis, and impaired photosynthesis, as well as damaging cellular structures such as membranes and DNA6,7,8. One of the primary physiological responses to Cd stress is oxidative stress, which triggers excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anions (O₂•−), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂)9. Notably, Cd exposure has been shown to significantly increase H₂O₂ levels in plant systems, making it a useful marker for oxidative stress.

Electrochemical techniques offer sensitive and rapid methods to detect ROS, providing advantages over traditional spectrophotometric and chromatographic approaches3,4. In particular, chronoamperometry allows real-time monitoring of H₂O₂ production in plant cell suspensions, making it a reliable indicator of Cd-induced oxidative stress10.

Considering these factors, this study aimed to explore the potential of T. cacao L. as a sedentary bioindicator by quantifying H2O2 in cellular suspensions derived from seed explants exposed to Cd2+ ions. The suspensions were cultivated under controlled in vitro conditions utilizing a medium simulating the optimal environment for plant tissue development11. While previous studies have investigated Cd accumulation in cacao-growing soils16,17research on the use of cacao as an active bioindicator remains limited12,13. This study seeks to bridge that gap by exploring H₂O₂ quantification as a novel approach for assessing toxic metal contamination. The findings will contribute to understanding the role of cacao as an environmental sentinel and demonstrate the applicability of electrochemical techniques in the biomonitoring of toxic metal pollution. Such a methodology could provide a practical alternative for environmental monitoring, particularly in regions where conventional assessment methods are impractical or imprecise.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The following reagents were used in this study: calcium nitrate (PhytoTechnology Laboratories, analytical grade); potassium sulfate (Merk, analytical grade); Bacto agar (Biomark); Murashige & Skoog basal medium with vitamins (MS); 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D); 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BAP); dipotassium phosphate (99%, Merck, analytical grade); monopotassium phosphate (99.05%, Merck, analytical grade); H2O2 (30% v/v, Sigma-Aldrich), and sulfuric acid (Fischer, analytical grade). An electrode polishing kit (CH Instruments, Inc.) was also employed.

Equipment

Experiments were conducted using a laminar flow cabinet (Esco); autoclave (Tuttnauer); Olympus BX-41 microscope (Olympus Corporation); orbital shaker (WiseSheak); ultrasonic bath (Branson 3800); and a Neubauer chamber (AR Biotech). Electrochemical measurements were performed with a potentiostat (Biologic SP-150); ECLab software V11.26; platinum (Pt) working electrode; Ag/AgCl reference electrode (3 mol L−1 KCl); and graphite rod counter electrode.

Preparation of T. cacao L. cell suspensions

T. cacao L. pods were collected in the town of Mindo, Ecuador, (latitude: −0.0506,

longitude: −78.7788) in the province of Pichincha. The fruit was transported to the laboratory in a portable refrigerator. The disinfection process involved extracting and rinsing the T. cacao L. seeds with distilled water to remove the mucilage completely, followed by washing with a chlorine solution, testing concentrations between 3.5 and 5% for 10 min. The seeds were then rinsed three times with distilled water inside a laminar flow chamber14.

Callus formation was induced using MS medium containing hydrated calcium nitrate (1967 mg L−1), potassium sulfate (1559 mg L−1), sucrose (40 g L−1), 6-BAP (4 mg L−1), 2,4-D (2 mg L−1), and 7 g of agar15.

Subsequently, four explants per flask were planted in MS medium and stored at room temperature under dark conditions for 30 days to allow for callus multiplication14. The same culture medium was used for both multiplication of callus and sowing.

To prepare the cellular suspensions, approximately 1 g of the formed callus was added to 50 mL of the aforementioned MS growing medium (excluding the agar). The mixture then underwent orbital agitation15.

Cells were counted by taking a sample of the suspension inside the flow chamber, which was subsequently introduced into the Neubauer chamber. The cells were observed and counted using an Olympus BX-41 microscope. Cellular concentration (CC) was calculated using Eq. (1):

Hydrogen peroxide production assessment

The electrochemical system consisted of a Pt working electrode, a graphite rod counter electrode, and a Ag/AgCl (3 mol L−1 KCl) reference electrode. The Pt working electrode was cleaned using successive mechanical polishing with alumina powder of decreasing grain sizes (1, 0.3, and 0.05 μm)16 for 3 min for each grain size. Subsequently, electrochemical cleaning was performed via cyclic voltammetry in a 0.5 mol L−1 H2SO4 solution, with potentials ranging from −0.300 to 1.800 V vs. Ag/AgCl at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1.

Chronoamperometric measurements were performed in cell suspensions with a turbidity of 15 NTU and CC of 3 × 104 cells mL−1. Turbidity of initial cell solution 25 NTU and the CC of the stock solution was of 5 × 10⁴ cells mL−1.

Calibration curves were constructed by measuring chronoamperometric currents in H2O2 standard solutions at concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 1.4 µmol L−1 in a phosphate buffer solution (PBS) at pH 5.7. The standard addition method was employed to determine H2O2 concentrations to minimize the dependency between the target signal current and possible sample matrix interference26. Method performance parameters, including sensitivity, detection limit, quantification limit, precision, and accuracy, were evaluated. The arithmetic mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and percent recovery (R%) were also calculated for the measurements (n = 5). The percent coefficient of variation (CV%) values were assessed according to the acceptable limits described in the AOAC (2012) guidelines for laboratory chemical method validation in dietary supplements and botanicals. These were set at CV < 11% for reproducibility and precision and between 80 and 115% for R% values.

For the respective cellular stress experiments, 1:10 dilutions of aqueous suspensions were prepared using CdSO4 concentrations of 5, 20, 50, and 100 µmol L−1 4. Cells were exposed to the stressing agent for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 h. H2O2 quantification was performed using the standard addition method in a 0.1 mol L−1 PBS at pH 5.7. Aliquots of 20 µL were added from a 0.02 mol L−1 H2O2 standard solution every 20 s16,17.

Results and discussion

Disinfection protocol for T. cacao L. explants

The most efficient disinfection protocol for T. cacao L. explants was determined by evaluating bacterial contamination, fungal contamination, and oxidation. The optimal method involved immersing the cacao seeds, with mucilage removed, in a 3.5% chlorine solution for 10 min (Table 1), followed by three rinses with distilled water in a laminar flow chamber. This approach minimized oxidation while effectively reducing microbial contamination, preventing inhibition of seed germination. This protocol aligns with reported plant tissue disinfection methods, where appropriate NaClO concentrations have been shown to reduce contamination without significantly affecting germination or development18. The selection of a 3.5% chlorine concentration effectively balanced microbial decontamination while maintaining explant viability, ensuring a suitable starting point for subsequent experimental procedures.

Induction and multiplication of embryogenic callus

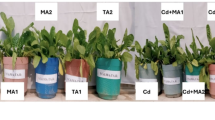

Embryogenic callus formation in T. cacao L. seeds began seven days after sowing in MS medium. The calluses were kept in a dark environment to promote optimal growth. After 15 days, their successful development confirmed that the MS medium provided suitable conditions for explant cultivation (Fig. 1). After 30 days, an additional multiplication step was carried out using the same MS medium. Figure 1d shows the embryogenic callus alongside clusters of undifferentiated cells. The MS medium, enriched with macro- and micronutrients, vitamins, and cytokinins, created optimal circumstances for callus growth under in vitro conditions.

The induction and multiplication of embryogenic callus in T. cacao L. are critical steps in somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration protocols. In this study, embryogenic callus formation began seven days after sowing in MS medium under dark conditions, consistent with established methodologies. Subsequent sub-culturing after one month further promoted callus proliferation.

The enriched MS medium provides essential support for in vitro plant tissue culture. The inclusion of plant growth regulators, such as 2,4-D, a synthetic auxin, and 6-BAP, a cytokinin, plays a key role in callus induction and somatic embryogenesis. Research has demonstrated that 2,4-D promotes cell division and dedifferentiation, while 6-BAP enhances cell proliferation and differentiation. Their synergistic effect has been shown to facilitate embryogenic callus development in cacao19.

Regular sub-culturing onto fresh medium is essential for maintaining cell viability, preventing necrosis, and ensuring continued callus proliferation. This practice replenishes nutrients and growth regulators while eliminating inhibitory metabolites. Studies have confirmed that sub-culturing enhances callus growth and embryogenic potential in cacao tissue cultures19.

Our results are consistent with those of previous studies highlighting the positive influence of 2,4-D and 6-BAP supplementation on callus development20. To prevent cell death and aggregation, subcultures were periodically transferred to fresh medium22. Auxins such as 2,4-D are frequently used to induce embryogenic callus, as they regulate key physiological and molecular processes involved in somatic embryogenesis. Consistent with our observations, Hazubska-Przybył et al.27 reported that the combination of 2,4-D and 6-BAP enhances somatic embryo formation from embryogenic callus structures.

Cell counting

Cell counting was conducted by taking a small aliquot from each suspension, placing it in the Neubauer chamber, and examining it under a microscope. Figure 2 shows optical microscope images of the cells at 10x magnification, showing fully disaggregated cells, confirming the suspensions were suitable for monitoring cell growth. Additionally, no large clusters of cells were observed.

Evaluation of analysis method

Figure 3 shows the cyclic voltammetry responses recorded over 10 consecutives cycles of the electrochemical cleaning process. As described in the experimental section, the working electrode was rinsed before each measurement to prevent analyte interference that could lead to adsorption on the electrode surface; such adsorption may introduce impurities and result in non-stable electrochemical responses23. The voltammograms exhibit characteristic peaks corresponding to a H2SO4 solution at a pure poly-crystalline Pt surface24.

According to Strandberg et al.10the voltammogram in Fig. 3 can be divided into four regions: (i) the hydrogen adsorption/desorption region (\(\:Pt+{H}^{+}+{e}^{-}\rightleftarrows\:Pt-\:{H}_{ads}\)) between 0.00 and −0.2 vs. Ag/AgCl; (ii) the double layer region between 0.1 and 0.4 vs. Ag/AgCl; (iii) the oxidation region during the anodic scan from 0.7 vs. Ag/AgCl up to the upper potential limit; and (iv) the reduction region during the cathodic scan from at an upper potential limit down to 0.6 Ag/AgCl.

To assess the electrocatalytic activity of Pt in the H2O2 reaction, cyclic voltammograms were recorded in a 0.1 mol L−1 PBS saturated with N2 (Fig. 4). When the Pt electrode was cycled within a potential window ranging from 0.7 V to −0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl, a distinct redox peak was observed at 0.25 V, corresponding to the H2O2 reduction reaction. The current magnitude increased proportionally with H2O2 concentration, confirming the catalytic activity of the Pt electrode toward H2O2 reduction, consistent with prior studies25.

The calibration plot was constructed using chronoamperometry at a potential of −0.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl over a 15 minute period. Figure 5 shows the resulting calibration curve, with the insert displaying the chronoamperogram indicating the electrocatalytic response of the Pt electrode across varying H2O2 concentrations (0.3–1.4 µmol L−1). The maximum reduction currents corresponding to each H2O2 concentration increased as the potential was adjusted to −0.3 V. However, saturation of the sensor was observed after the addition of 1.4 µmol L−1 H2O2. The limits of detention and quantification were calculated using the formula 3 × SDblank/slope of the calibration curve and 10 × SDblank from the blank/slope of the calibration curve, respectively (Table 2). The analytical sensitivity was determined to be 0.4959 mA (µmol L−1)−1.

Hydrogen peroxide quantification in cell suspensions

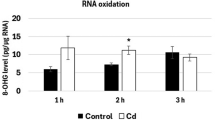

While ROS are also metabolic by-products in processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, and nitrogen fixation in plants, their concentrations are normally regulated by scavenging agents, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione reductase, and peroxidase. Thus, living organisms can maintain harmless levels of ROS concentrations during these processes. However, under stress conditions, this balance is disrupted, resulting in the overproduction of ROS and a subsequent oxidative burst a critical and rapid detoxification response in plants10,27,28. Previous studies have indicated that a H2O2 concentration of just 2.5 mmol L−1 in the medium can initiate a series of chain reactions that irreversibly damage DNA, thereby affecting cells’ replication mechanisms29. Conversely, at concentrations exceeding 2.5 mmol L−1, H2O2 can damage enzymatic cellular compounds containing Ca2+30 and attack proteins and lipids within cell membranes, causing lysis31. The control experiment, in which the suspension was not exposed to CdSO4, was conducted in PBS at pH 5.7, resulting in a mean H2O2 concentration of 0.16 µmol L−1 (Fig. 6a). Figure 6b–e illustrates the relationship between generated H2O2 concentrations and exposure time in T. cacao L. cells subjected to different concentrations of CdSO4. There was no change in H2O2 concentration in the control medium (Fig. 6a) over 6 h, suggesting that, in the absence of oxidative stress, natural ROS scavenging agents effectively maintain H2O2 concentration at a constant level.

After 1 h of the cell suspension’s exposure to CdSO4 solutions, the quantified H2O2 at the electrode was considerably higher than that in the unstressed suspension (Fig. 6b–e). Thus, 1 h was determined to be the minimum time required to detect H2O2 in the system due to the oxidative stress process. As shown in Fig. 6, the cell suspension’s response to increasing CdSO4 concentrations is consistent with previously reported data32; specifically, increasing the amount of Cd2+ in the medium led to higher H2O2 production by cells. The suspension exposed to 5 µmol L−1 CdSO4 (Fig. 6b) exhibited the lowest H2O2 concentration over time, while the highest concentration corresponded to the suspension exposed to 100 µmol L−1 CdSO4 (Fig. 6c). In all cases, peak H2O2 production was quantified at 3 h, regardless of CdSO4 concentration. Overall, Fig. 6 shows that after 1 h of exposure to different CdSO4 concentrations, H2O2 concentrations are higher than those in the control medium, supporting the occurrence of an oxidative burst.

According to the graph shown in Fig. 6, the highest H2O2 concentrations after adding CdSO4 to the cell suspensions occur at 1, 3, and 5 h. Each peak in H2O2 concentration can indicate an oxidative burst at the respective CdSO4 concentration. Conversely, the minimum H2O2 concentrations at 2 and 4 h likely correspond to periods wherein the cells gradually recover equilibrium, as these concentrations are the same as or very close to those for the control, 0.16 µmol L−1 H2O2 (Fig. 6a).

The results suggest that the overproduction of H2O2 in cell suspensions of T. cacao L. seeds was related to the plant’s defense mechanism against Cd2+ ions. Upon exposure to the metal, cell surface receptors recognize it, stimulating localized H2O2 production. H2O2 delays germination, allowing cells more time to activate their defense mechanisms, which contributes to resistance to Cd2+ stress. However, cell suspension behavior after 5 h of CdSO4 exposure suggests that T. cacao L. seed cells lose their capacity to re-establish equilibrium H2O2 concentrations beyond this duration. This is evidenced by the increased production of H2O2 in all suspensions, regardless of CdSO4 concentration, which fails to return to the baseline H2O2 concentration observed in the control. Notably, cell suspensions exposed to 100 µmol L−1 CdSO4 (Fig. 6c) showed the lowest capacity for recovery.

The addition of H2O2 is a commonly used method to induce cellular oxidative stress, typically requiring H2O2 concentrations greater than 100 µmol L−133,34. According to Fig. 6, after 5 h of exposure, cell apoptosis could occur due to the overproduction of H2O2 caused by stress from the contaminating metal, thereby impairing the cells’ ability to recover. This reaction produces molecular oxygen through the catalase reaction, a very rapid reaction that drastically decreases H2O2 concentration within minutes35. Additionally, the results highlight the efficacy of intracellular antioxidant defenses against H2O2.

These findings support the potential of T. cacao L. as a bioindicator for Cd contamination in the environment. The observed correlation between Cd exposure and H₂O₂ production suggests that oxidative stress responses in cacao cells can serve as an early warning system for toxic metal pollution. The plant’s ability to accumulate Cd and generate a measurable oxidative stress response highlights its suitability for biomonitoring applications, particularly in regions where cacao cultivation is economically and environmentally important. Furthermore, the progressive loss of cellular recovery capacity under prolonged Cd exposure underscores the potential long-term impacts of toxic metal contamination on cacao plantations.

Integrating electrochemical H₂O₂ quantification into environmental monitoring programs could provide a rapid and sensitive method for detecting metal-induced oxidative stress, reinforcing the role of T. cacao L. as a practical and sustainable bioindicator for assessing environmental Cd contamination. Additionally, recent studies have highlighted the critical function of phenolic compounds in plant defense mechanisms against Cd stress. These non-enzymatic antioxidants act as ROS scavengers and metal chelators, thereby mitigating oxidative damage and enhancing stress tolerance42. T. cacao L. phenolic compounds may play a crucial role in maintaining redox balance under Cd stress, complementing enzymatic defenses. Future studies exploring this interaction could further strengthen the potential of T. cacao L. as a biomonitor for Cd contamination.

Conclusion

The determination of H₂O₂ via chronoamperometry using Pt as the working electrode proved to be an effective methodology for Cd quantification, achieving detection and quantification limits of 0.012 and 0.389 µmol L−1, respectively. The findings showed that T. cacao L. responds to Cd stress through increased H₂O₂ production, demonstrating its potential as a sedentary bioindicator for environmental contamination. The observed correlation between Cd levels and oxidative stress marker suggests that T. cacao L. could serve as an efficient tool for monitoring toxic metal pollution in agricultural regions. Additionally, the results highlight the effectiveness of the plant’s defense mechanisms, as evidenced by its immediate oxidative response to Cd-induced stress.

To establish T. cacao L. as a bioindicator, field-based studies should be conducted to validate laboratory findings under real environmental conditions. Standardized protocols for H₂O₂ quantification in cacao tissues should be developed to ensure reliable and reproducible results. Moreover, policymakers should consider incorporating T. cacao L. into environmental monitoring programs, particularly in regions where cacao cultivation is a major economic activity. Regulatory agencies could leverage these findings to establish early warning systems for Cd contamination, helping to safeguard both agricultural sustainability and public health.

Data availability

Data “available on request”: lmfernandez@puce.edu.ec.

References

Zhou, Q. et al. An appealing tool for assessment of metal pollution in the aquatic ecosystem. Anal. Chim. Acta. 606, 135–150 (2008).

El-SiKaily, A. & Shabaka, S. Biomarkers in aquatic systems: advancements, applications and future directions. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 50, 169–182 (2024).

Biomonitoring of Pollutants in the Global South. Biomonitoring of Pollutants in the Global South. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-1658-6/COVER

Vargas Jentzsch, P. et al. Distinction of Ecuadorian varieties of fermented cocoa beans using Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem. 211, 274–280 (2016).

Wexler-Goering, L. & Alvarado-Marenco, P. Fine and flavor cocoa: key aroma compounds and their behavior during processing. Agronomía Mesoamericana. 35, 59679–59679 (2024).

Reygaert, W. C. & Reygaert, W. C. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiology 2018 3:482 4, 482–501 (2018).

Mansoor, S. et al. Biochar mediated remediation of emerging inorganic pollutants and their toxicological effects on plant and soil health. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 25, 1612–1642 (2025).

Davidova, S., Milushev, V. & Satchanska, G. The Mechanisms of Cadmium Toxicity in Living Organisms. Toxics 12, (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Cadmium-induced genomic instability in arabidopsis: molecular toxicological biomarkers for early diagnosis of cadmium stress. Chemosphere 150, 258–265 (2016).

Xu, Q. et al. In vivo monitor oxidative burst induced by Cd2 + stress for the oilseed rape (Brassica Napus L.) based on electrochemical microbiosensor. Phytochem Anal. 21, 192–196 (2010).

Wampash Najamtai, G. B., Nieves, N., Barriga Castillo, F. M. & Implementación G. R. adecuación y Valoración de Un sistema de climatizado, Para El área de incubación Del laboratorio de micropropagación Del campus Juan Lunardi Cantón paute. Provincia Del. Azuay 1 (2011).

Baker, C. J. & Mock, N. M. A method to detect oxidative stress by monitoring changes in the extracellular antioxidant capacity in plant suspension cells. Physiol. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 64, 255–261 (2004).

Akter, S., Khan, M. S., Smith, E. N. & Flashman, E. Measuring ROS and redox markers in plant cells. RSC Chem. Biol. 2, 1384–1401 (2021).

Balladares, C. et al. Physicochemical characterization of Theobroma cacao L. sweatings in Ecuadorian Coast. Emir J. Food Agric. 28, 741–745 (2016).

Montero-Jiménez, M. et al. Evaluation of the cadmium accumulation in Tamarillo cells (Solanum betaceum) by indirect electrochemical detection of Cysteine-Rich peptides. Molecules 2019. 24, 2196 (2019).

Alvarez-Paguay, J., Fernández, L., Bolaños-Méndez, D., González, G. & Espinoza-Montero, P. J. Evaluation of an electrochemical biosensor based on carbon nanotubes, hydroxyapatite and horseradish peroxidase for the detection of hydrogen peroxide. Sens Biosensing Res 37, (2022).

Fernández, L. et al. Electrochemical sensor for hydrogen peroxide based on Prussian blue electrochemically deposited at the TiO2-ZrO2–Doped carbon nanotube glassy carbon-Modified electrode. Front. Chem. 10, 884050 (2022).

Lopes da Silva, A. L. et al. Chemical sterilization of culture medium: A low cost alternative to in vitro establishment of plants. Scientia Forestalis/Forest Sci. 41, 257–264 (2013).

Dar, S. A., Nawchoo, I. A., Tyub, S. & Kamili, A. N. Effect of plant growth regulators on in vitro induction and maintenance of callus from leaf and root explants of Atropa acuminata royle ex Lindl. Biotechnol. Rep. 32, e00688 (2021).

Hesami, M., Daneshvar, M. H., Yoosefzadeh-Najafabadi, M. & Alizadeh, M. Effect of plant growth regulators on indirect shoot organogenesis of Ficus religiosa through seedling derived petiole segments. J. Genetic Eng. Biotechnol. 16, 175–180 (2018).

Puad, N. I. M., Mze, S. A. I., Azmi, A. S. & Abduh, M. Y. The influence of plant growth regulators and light supply on bitter cassava callus initiation for starch production. IIUM Eng. J. 25, 1–11 (2024).

Curtis, W. R. & Emery, A. H. Plant Cell Suspension Culture Rheology.

Elgrishi, N. et al. A practical beginner’s guide to Cyclic voltammetry. J. Chem. Educ. 95, 197–206 (2018).

Strandberg, L. et al. Comparison of Oxygen Adsorption and Platinum Dissolution in Acid and Alkaline Solutions Using Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance. ChemElectroChem 9, (2022).

Okada, H., Mizuochi, R., Sakurada, Y., Nakanishi, S. & Mukouyama, Y. Electrochemical oscillations (Named oscillations H and K) during H2O2 reduction on Pt electrodes induced by a local pH increase at the electrode surface. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 76512 (2021).

Bagur, G., Sánchez-Viñas, M., Gázquez, D., Ortega, M. & Romero, R. Estimation of the uncertainty associated with the standard addition methodology when a matrix effect is detected. Talanta 66, 1168–1174 (2005).

Apostol, I., Heinstein, P. F. & Low, P. S. Rapid stimulation of an oxidative burst during elicitation of cultured plant cells: role in defense and signal transduction. Plant. Physiol. 90, 109–116 (1989).

Luna, C. M., González, C. A. & Trippi, V. S. Oxidative damage caused by an excess of copper in oat leaves. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 35, 11–15 (1994).

Szmigiero, L. & Studzian, K. H202 as a DNA fragmenting agent in the alkaline elution interstrand crosslinking and DNA-Protein crosslinking assays. Anal. Biochem. 168(1), 88–93 (1988).

Sato, H. et al. Hydrogen peroxide mobilizes Ca2 + through two distinct mechanisms in rat hepatocytes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30, 78–89 (2009).

Horn, A. & Jaiswal, J. K. Structural and signaling role of lipids in plasma membrane repair. in Current Topics in Membranes vol. 84 67–98Academic Press Inc., (2019).

Guo, B., Liu, C., Liang, Y., Li, N. & Fu, Q. Salicylic acid signals plant defence against cadmium toxicity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 20 Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20122960

Ransy, C., Vaz, C., Lombès, A. & Bouillaud, F. Use of H2O2 to cause oxidative stress, the catalase issue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9149 (2020).

Park, C. S., Yoon, H. & Kwon, O. S. Graphene-based nanoelectronic biosensors. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 38, 13–22 (2016).

Sule, R. O., Condon, L. & Gomes, A. V. A Common Feature of Pesticides: Oxidative Stress—The Role of Oxidative Stress in Pesticide-Induced Toxicity. Oxid Med Cell Longev 5563759 (2022). (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank ESPE-Ecuador (Departamento de Ciencias de la Vida y Agricultura) for its technical assistance.

Funding

Dirección de Investigación de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The Author Contributions section is mandatory for all articles, including articles by sole authors. If Conceptualization: L.F.; Data curation; M.J.G.-L., P.B., L.F. and P.E.-M.; Formal analysis: L.F., M.J., and P.E.-M.; Funding acquisition: L.F. and P.E.-M.; Investigation: M.J.G.-L., P.B., L.F., and P.E.-M.; Methodology: M.J.G.-L., M.J., A.O.G and L.F.; Project administration: L.F.; Resources: L.F.and P.E.-M.; Supervision: L.F.; Validation: P.B., L.F., J.D.S. and D.B.-M.; Visualization: A.R., L.F. and P.E.-M.; Roles/Writing - original draft: L.F.; and P.E.-M.; Writing - review & editing: A.R, P.E.-M.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández, L., Espinoza-Montero, P.J., Gallegos-Lovato, M.J. et al. Evaluation of Theobroma cacao L. as a bioindicator for cadmium contamination through H2O2 electrochemical analysis. Sci Rep 15, 26715 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11715-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11715-2