Abstract

Numerous studies have shown that caffeine facilitates cognition, particularly memory, when consumed before learning and immediately tested. However, most of this evidence relates to its effects during encoding, and the role in memory consolidation remains unclear. A key study demonstrated that caffeine administered after learning can enhance object recognition memory consolidation by improving discrimination between previously seen targets and similar lures. Here, we investigated the effects of post encoding caffeine on the consolidation of face recognition memory using a randomized, double-blind design. Participants (N = 97) viewed ten generated faces on Day 1 and then received 200 mg of caffeine or placebo. On Day 2, they completed a recognition task under two conditions: Present condition (original face with five similar distractors) or Absent condition (six similar distractors) adding a “none of the above” option. The results showed that, contrary to our expectation, caffeine consumption did not improve the consolidation of face recognition memory. Instead, we observed a general impairment in recognition performance, suggesting a reduced ability to distinguish previously encountered from novel but similar faces. These findings discuss the idea of caffeine as a general cognition enhancer and aligned with studies suggesting it enhances global processing at the expense of detailed discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caffeine is the world’s most commonly used psychoactive1 and nootropic substance2. Numerous studies have observed its stimulating effects, which enhance alertness, wakefulness, motivation, motor activity3,4 and visual attention5,6 Additionally, caffeine has been shown to mitigate habituation effects7 and reduce processing speed in inhibitory control tasks8.

Generally, these studies have focused on caffeine administration before information encoding. As a result, they have not sufficiently distinguished whether its possible enhancing effects influence learning itself or the subsequent consolidation of memories.

Research on caffeine’s effect on memory consolidation, however, remains debated. On the one hand, studies in rodents have demonstrated a positive effect of caffeine when administered post learning9,10. Angelucci et al. (2002)11 showed that relatively low doses (0.3-3 mg/kg) of caffeine improved consolidation in tasks such as the water maze, active avoidance, and inhibitory avoidance. More recently, Días et al. (2022)12 reported that caffeine enhanced the consolidation of the temporal (‘what-when’) and spatial (‘what-where’) components of episodic-like memory in rodents. On the other hand, evidence from human studies on the effects of caffeine on memory consolidation remains mixed. One study found that caffeine improved object recognition memory by enhancing the ability to discriminate between familiar and similar objects when the target was absent13. In contrast, no improvements were observed in motor memory consolidation following post practice caffeine administration14, nor in incidental word learning15. Beyond human models, research in invertebrates has also provided nuanced findings. In honey bees, caffeine was found to modulate performance during encoding, with high doses reducing responsiveness, while having no effect on early long-term memory consolidation16.

While much of the research on caffeine and memory has focused on general or object based memory tasks, less is known about its effects on more complex and socially relevant forms of memory, such as face recognition. The ability to recognize faces is a widely utilized skill in everyday life. It has been observed that this ability could be modulated by individual variables, such as visual imagery capacity17. Furthermore, it could be totally or partially affected in people who acquire or genetically have prosopagnosia (facial blindness) or people with autistic traits18. The face recognition ability could also be decisive in specific areas such as eyewitness memory, where victims and/or witnesses could play a crucial role in legal decisions through their choices in identification lineups19 or in the construction of identikits20. For this reason, multiple studies have focused on the effect that different legal and illegal drugs have on this ability21.

To our knowledge, no studies have assessed the influence of caffeine on the consolidation of face recognition memory. Following the study of Borota et al., (2014)13, we hypothesized that a dose of 200 mg would positively affect human memory consolidation in a recognition task. Therefore, the present study evaluated the effect of caffeine on the consolidation of human face recognition using a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The experiment was conducted over two days. On Day 1, participants viewed ten artificially generated faces and immediately received either 200 mg of caffeine, the lowest dose that has been proposed to improve consolidation13, or a placebo. On Day 2, they completed a recognition task under either target present or target absent condition.

Results

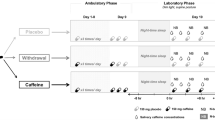

To examine the effects of post encoding caffeine ingestion on the consolidation of face recognition memory, a randomized, double-blind study was conducted. A total of 97 participants viewed ten artificially generated faces on Day 1 before receiving either 200 mg of caffeine or a placebo. On Day 2, they underwent a recognition task with two conditions: Present (the original face alongside five similar distractors) and Absent (six similar distractors), including a “none of the above” option (Fig. 1). The distractors used were also artificially generated faces.

Experimental procedure. On Day 1 participants performed a Training session immediately received either 200 mg of caffeine or a placebo. At the same time on Day 2 participants performed a Testing session. In the Present condition, participants’ responses were classified as hits (selection of the original face), false alarms (selection of a distractor), or incorrect rejections (choosing “none of the above” despite the original face being present). In the Absent condition, responses were categorized as false alarms (selection of a distractor) or correct rejections (The correct response is to select the “None of the above”).

In the Present condition, participants’ responses were classified as hits, false alarms, or incorrect rejections. In the Absent condition, responses were categorized as false alarms or correct rejections (see Table 1).

To evaluate overall performance across both conditions, we conducted an integrated analysis using a two-way ANOVA with conditions (Present vs. Absent) and group (Caffeine vs. Placebo) as between-subject factors. The dependent variable was the Correct choice rate, defined as the proportion of hits in the Present condition and correct rejections in the Absent condition. This analysis revealed no significant interaction between condition and group (Fcondition*group(1,95) = 0.06 p = 0.80, Fig. 2), indicating that the effect of condition on performance did not differ by group. However, we found that subjects performed better in the Present condition (Fcondition(1,95) = 31.51 p < 0.001, η2 = 0.25, Fig. 2). Furthermore, the Caffeine group showed significantly less correct choices than the Placebo group (Fgroup(1,95) = 4.27 p = 0.04, η2 = 0.04, Fig. 2). In the same way, we conducted a two-way ANOVA with conditions (Present vs. Absent) and group (Caffeine vs. Placebo) as between-subject factors analysis of the False alarm rate. This analysis revealed no significant interaction between condition and group (Fcondition*group(1,95) = 0.22 p = 0.63, Fig. 2). However, the Absent condition showed a significantly higher False alarm rate compared to the Present condition (Fcondition(1,95) = 127.24 p < 0.001, η2 = 0.57, Fig. 2). Furthermore, the Caffeine group exhibited a higher False alarm rate with respect to the Placebo group (Fgroup(1,95) = 7.47 p = 0.008, η2 = 0.07, Fig. 2). The variable of Incorrect rejection rate (when in the presence of the original face, they responded that it was none of the options) was only analyzed in the Present condition because the Absent condition does not have this option. It was observed that the groups had no differences for these elections (Fgroup(1,48) = 1.56 p = 0.21).

Further, to ensure that these effects were not influenced by potential confounders, we conducted an additional ANCOVA. On the Correct choice rate, the Covariate BMI (Body mass index) did not have a significant effect (F(1,95) < 0.000, p = 0.98), neither state anxiety (State anxiety subscale of the STAI anxiety test) (F(1,95) = 0.33, p = 0.56), time awake (Total waking hours from wake-up to the time of the Training session) (F(1,95) = 1.42, p = 0.23), or regular daily caffeine consumption (F(1,95) = 2.04, p = 0.15). Further, the same analysis was conducted for the False alarm rate. The Covariate BMI did not have a significant effect (F(1,95) = 0.21, p = 0.64), neither state anxiety (F(1,95) = 0.54, p = 0.46), time awake (F(1,95) = 1.18, p = 0.28), or regular daily caffeine consumption (F(1,95) = 1.65, p = 0.20).

Finally, confidence-accuracy characteristic analysis revealed that the exponential relationship typically observed between responses and confidence is preserved in the Caffeine group (i.e., response rate increases as self-reported confidence increases), despite this group’s lower proportion of correct recognition compared to the placebo group at all confidence levels (Fig. 3).

Post hoc statistical power analysis

A post hoc power analysis was conducted using an alpha level of 0.05, the observed effect sizes for each factor, and a final sample size of 97 subjects. For the Correct choice rate, the main effect of condition (Present vs. Absent) demonstrated a large effect size (f = 0.58) and achieved a power of 0.99. The main effect of the group (Caffeine vs. Placebo) showed a small to medium effect size (f = 0.20) with moderate power of 0.52, indicating a limited but acceptable capacity to detect differences between groups. Regarding the False alarm rate, the main effect of the condition revealed a large effect size (f = 1.15) with maximal statistical power of 1.00. The main effect of the group showed a moderate effect size (f = 0.27) and moderate power of 0.78, suggesting a reasonable likelihood of detecting group differences.

Control measures

In the Present condition, the groups did not differ in baseline activation levels, as measured by STAI subscale for state anxiety22 (Caffeine group: 35.18 ± 4.69 points, Placebo group: 35.13 ± 5.62 points, t(48) = 0.03, p = 0.97), nor in their usual daily coffee consumption (Caffeine group: 396.42 ± 205.44 mg, Placebo group: 402.27 ± 177.60 mg, t(48) = −0.10, p = 0.91), body mass index (Caffeine group: 24.31 ± 3.64 kg/m², Placebo group: 24.72 ± 5.02 kg/m², t(48) = −0.33, p = 0.73), or time awake at the moment of the Training session (Caffeine group: 7:26 ± 2:48 h, Placebo group: 6:37 ± 2:41 h, t(37) = 0.93, p = 0.35). Additionally, we analyzed whether the groups were comparable in terms of attentional baseline in the Training session (Caffeine group: 7.83 ± 1.57 faces ‘Seen’, Placebo group: 8.05 ± 1.04 faces ‘Seen’, t(48) = −0.44, p = 0.66). In the Absent condition, the groups did not differ in baseline activation levels, as measured by the state anxiety test (Caffeine group: 36.52 ± 6.50 points, Placebo group: 34.70 ± 7.38 points, t(45) = 0.89, p = 0.37), nor in their usual daily coffee consumption (Caffeine group: 365.21 ± 201.37 mg, Placebo group: 369.16 ± 217.87 mg, t(45) = −0.06, p = 0.94), body mass index (Caffeine group: 24.47 ± 3.14 kg/m², Placebo group: 24.38 ± 6.34 kg/m², t(45) = 0.06, p = 0.95), or time awake at the moment of the Training session (Caffeine group: 7:13 ± 2:41 h, Placebo group: 6:55 ± 3:16 h, t(39) = 0.32, p = 0.74). Additionally, we analyzed whether the groups were comparable in terms of attentional baseline in the Training session (Caffeine group: 8.00 ± 1.82 faces ‘Seen’, Placebo group: 8.54 ± 1.22 faces ‘Seen’, t(45) = −1.16, p = 0.25). Finally, we explored whether the timing of the Training session within the Caffeine group (including both conditions) influenced the results by comparing participants who received caffeine earlier versus later in the day. Since all sessions took place between 9am and 5pm, participants in the Caffeine group were categorized into Early and Late intake subgroups based on the time of administration relative to the Training session. The variable analyzed was the percentage of Correct choices (hits or correct rejection) in the recognition task during the Testing session. No significant differences were found between the subgroups (Early intake: 42.27 ± 17.70; Late intake: 39.69 ± 20.23; t(49) = 0.48, p = 0.62).

Discussion

Contrary to our expectations, caffeine appeared to have a detrimental effect on the consolidation of face recognition memory. This was evidenced in the integrated analysis across Present and Absent conditions, which revealed that the Caffeine group after learning exhibited a significantly lower Correct choice rate and a higher False alarm rate compared to the Placebo group. These effects were consistent across both conditions, indicating a general disruption in recognition accuracy rather than a condition specific effect. Taken together, the results suggest that caffeine, when administered post encoding, impairs the ability to reliably discriminate previously seen faces from similar distractors, disrupting rather than enhancing the consolidation of face memory representations. In line with these findings, the CAC curves revealed that the performance of the Caffeine group was consistently inferior to that of the Placebo group across all confidence levels. However, the typical confidence-accuracy relationship, characterized by increasing accuracy with higher confidence, remained preserved in both groups.

While previous studies on the effect of caffeine on memory consolidation have produced mixed findings, to our knowledge, none have reported a consistent detrimental effect on face recognition performance following caffeine intake after encoding. One potential explanation involves heightened physiological arousal induced by caffeine, which is known to increase the sympathetic nervous system and the HPA axis23,24,25. This elevated arousal may enhance the encoding of post learning stimuli (e.g., faces encountered after the experimental session), increasing interference with consolidation of the original encoded faces. This interpretation aligns with the idea that arousal could both facilitate memory consolidation and increase competition between newly encoded and previously learned information, leading to greater susceptibility to interference26. This explanation is consistent with Schwabe et al. (2010)27, who proposed that arousal not only influences how much we remember but also the quality of what is remembered. Specifically, arousal can shift memory processing from flexible, hippocampus dependent encoding to more rigid, habit based learning. If caffeine induced arousal pushed participants to this kind of processing, it may have reinforced the encoding of new faces encountered after the experiment, at the expense of consolidating the original ones. In our study, the Caffeine group may have unintentionally encoded post experiment faces (the faces they encountered incidentally after leaving the lab at the end of the Training session) more strongly, which interfered with the consolidation of the previously learned faces. This would also be in line with evidence suggesting that caffeine benefits the encoding of incidental information2.

To our knowledge, the only study that observed a beneficial effect of caffeine on recognition memory consolidation in humans was Borota et al. (2014)13, which observed that a dose of 200 mg of caffeine could benefit the ability to discriminate between similar and previously seen objects. One possible explanation for the differences between their results and those found in our study could be the substantial difference between the information learned in both studies. In the cited study the stimuli consisted of cartoon-style drawings of objects. These stimuli are rarely found in post-laboratory experiences, that is, they are difficult to compete with stimuli external to the experiment. However, a later replication by Aust & Stahl (2020)28 found that the enhancing effect reported by Borota et al., (2014)13 may not be as robust. They proposed that observed improvement could reflect a reversal of the withdrawal rather than true cognitive enhancement. This phenomenon occurs frequently because, by orders from the experimenter, the participants avoid consuming caffeinated beverages before the experiment. Another key difference concerns participants’ usual caffeine intake. While Borota et al. (2014)13 excluded high caffeine consumers (> 500 mg/week), our sample had a substantially higher average intake (~ 400 mg/day), which is consistent with typical consumption patterns in Argentina, where yerba mate is a culturally prevalent caffeinated beverage29. Aust & Stahl (2020)28, whose participants had similar intake levels (~ 427 mg/day), found no effect of caffeine on mnemonic discrimination, and reported no association between habitual intake and performance. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the higher baseline caffeine use alone explains the absence of an effect in our study. While caffeine intake was included as a covariate in our analysis, the potential attenuation of acute effects due to tolerance in high consumers cannot be entirely ruled out. Future studies may explore this possibility more directly.

Another possible explanation stems from caffeine’s documented enhancement of global processes29, which biases individuals towards holistic rather than detail-focused processing. In a recognition memory task, this bias can lead to increased false alarms, as participants may rely on general face similarities rather than discriminating specific features that distinguish the original face from a distractor (similar face). This occurs because global processing could favor the recognition of broad or contextual characteristics of the stimuli instead of discriminating between unique or specific details that differentiate a target stimulus from a lure one.

This tendency towards holistic processing may interact with other neurochemical effects of caffeine on memory consolidation mechanisms, particularly when the stimuli are faces. While object recognition might benefit from enhanced pattern separation mechanisms supported by norepinephrine or long-term potentiation13,30 face recognition engages a combination of featural and holistic processes31. Some evidence suggests that caffeine could elevate hippocampal acetylcholine levels via adenosine A1 receptors32, potentially disrupting memory consolidation by interfering with the replay of newly acquired memories. This may disproportionately affect face recognition, which is highly sensitive to subtle interference and less reliant on discrete features. If featural traces are weakened during consolidation, participants may become more dependent on holistic retrieval strategies. Holistic processing is generally beneficial and associated with better face recognition performance33. However, under certain conditions, such as when memory traces are degraded, relying primarily on holistic cues in the absence of robust featural information may be insufficient to support accurate recognition. This could result in reduced face memory performance, particularly when distinguishing among highly similar identities. Furthermore, faces have been shown to automatically capture attention, even when they are task-irrelevant34, and they engage distinct, domain-specific cognitive mechanisms compared to non-face objects, even those processed with high expertise35. Thus, caffeine may impair not only the strength of memory traces, but also the cognitive strategies used during retrieval, particularly for faces.

Within the limitations of the present work, we did not include an active control group, as recommended by Aust & Stahl (2020)28, which impeded us from controlling the subjects’ awareness of the pill received. Additionally, we did not measure reaction times, which could have provided further insights into the processing dynamics of the task36. Furthermore, it has been observed that impulsivity levels could modulate the effects of caffeine on memory tasks37 and this variable was not taken into account. Further, recent meta-analytic evidence suggests that caffeine could impair subsequent sleep for up to 8.8 h following ingestion38. A limitation of the present study is that some participants may have received caffeine within this sensitive time frame. Although the average bedtime in the Buenos Aires population is relatively late (approximately 00:30 a.m.)39, the timing of certain training sessions may have coincided with the window during which caffeine intake could affect nighttime sleep. To account for this, participants who received caffeine were divided into Early and Late intake subgroups, and no significant differences in task performance were observed between them. Nevertheless, the absence of post-training sleep data limits the ability to accurately assess whether caffeine had any residual effects on sleep that could have influenced memory performance. Another limitation of this study is the use of artificially generated faces as stimuli, without a pilot study to determine whether participants could distinguish between these and real faces. Previous research has indicated that artificially generated faces tend to be more difficult to memorize and are associated with higher false alarm rates40,41, which could have influenced participant performance. Nevertheless, the hit and correct rejection rates observed in the present experiment align with values reported in the eyewitness memory literature for face recognition tasks42. This suggests that participants’ performance did not substantially differ from expectations based on real face stimuli. Future studies should address this issue to further validate these findings.

In sum, the findings of this study suggest that caffeine could have a detrimental effect on the consolidation of face recognition memory. However, this effect could be influenced by the unique characteristics of faces as stimuli, given that humans possess a remarkable ability to recognize, encode, and consolidate face information. The facility with which face stimuli are encoded and their constant availability in everyday environments could play a key role in how caffeine modulates their consolidation. Future research should continue exploring both factors together, as caffeine is the most widely consumed psychoactive substance, and face recognition ability could be crucial in contexts such as the judicial system, where it could aid in the identification of criminals or help avoid wrongful convictions. The present study contributes to understanding how a widely used substance could influence a fundamental human ability.

Materials and methods

Study participants

The study sample consisted of 104 healthy adults between 18 and 40 years old (mean age = 27.30 ± 6.33 years), all of whom were habitual consumers of caffeine beverages. Participants were recruited through advertisements posted on the laboratory social media platforms. Two participants were excluded from the initial sample for not attending the Testing session and five participants were excluded from the analyses because they scored 0 points on the Testing session, indicating either lack of engagement or failure to understand the task, resulting in a final sample size of 97 participants.

Inclusion criteria were: age between 18 and 40 years and no current use of psychotropic medication or history of psychological illness. Exclusion criteria included a history of migraines or chronic headaches, ulcers or gastrointestinal disorders, high blood pressure, or cardiovascular problems. The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee (CEH), Faculty of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires (UBA). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. Participants were instructed to stop consuming caffeine from the night before starting the study and were instructed not to take naps during the two study days.

Groups

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups (Caffeine or Placebo), and randomly assigned to one of two testing conditions (Present or Absent condition).

Caffeine group: On Day 1, participants completed the Training session, followed by the administration of 200 mg of caffeine. On Day 2, they performed the Testing session under one of two conditions: Present condition (N = 28, 19 females) and Absent condition (N = 23, 15 females).

Placebo group: On Day 1, participants completed the Training session, followed by the administration of an inert capsule. On Day 2, they performed the Testing session under one of two conditions: Present condition (N = 22, 14 females) and Absent condition (N = 24, 19 females).

A number of participants were excluded from the final analyses. Two participants failed to return on Day 2 and were therefore not tested. Additionally, five participants who completed both sessions were excluded due to scoring zero on the Testing session, indicating either lack of engagement or failure to understand the task. These excluded participants were distributed as follows: one in the Present condition Placebo group, one in the Present condition Caffeine group, one in the Absent condition Caffeine group, and two in the Absent condition Placebo group.

Each participant completed the Testing session in only one condition (Absent or Present), such that measurements were taken from distinct samples.

The sample size was determined based on a previous study that examined the effect of caffeine on memory consolidation for a recognition task13. Although the original study did not report an effect size, we estimated it from their reported comparison between the 200 mg Caffeine group and the Placebo group (t(71) = 2.0, p = 0.049), which yielded an approximate Cohen’s d of 0.47. This corresponds to an f of approximately 0.24, considered a medium effect. Based on this estimate, we conducted an a priori power analysis using G*Power to determine the minimum sample size required to detect a main effect of Group (Caffeine vs. Placebo) in a 2 × 2 between-subjects’ ANOVA. With α = 0.05 and power = 0.80, the analysis indicated that a minimum total of 88 participants (44 per group) was required.

Experimental procedure

The experiments took place in a quiet room using a personal computer. Each participant wore headphones and sat in front of a 24-inch monitor. Before the study, medical staff conducted a health assessment to determine eligibility and the participants completed the questionnaires. Participants then returned to the laboratory on a different day to begin the experiment. On day 1 upon arrival, participants provided written informed consent before beginning the experiment. Then completed the Training session and immediately after received either 200 mg of caffeine or a placebo, administered with a glass of water. On Day 2, at the same time as the previous session, participants returned to the lab to complete the Testing session under identical conditions. All experiments were performed between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m.

Questionnaires

During the medical interview the BMI (Body mass index) of the subjects was recorded and they were asked about their usual caffeine consumption. To account for caffeine consumed through the local drink mate, we assumed a concentration of 250 mg per liter43,44, and a value of 200 mg of caffeine per cup of coffee (approximately 240 ml) was assumed45. Further, although the time of the study sessions was controlled, the specific time of awakening at the time of the Training session was not initially recorded due to an omission and was collected retrospectively. Since this question required retrospective recall, 15 participants were unable to provide an accurate response, so those data were not taken into account for the analysis. Further, prior to the Training session, participants completed the STAI subscale for state anxiety22 to assess the basal activation state.

Tasks

During the Training session (Day 1), participants received the following instruction: ‘You will now see a series of faces. The images will automatically scroll. Click the “Start” button and observe them carefully.’ They were then presented with 10 images of human faces (5 males and 5 females, selected randomly), each displayed at the center of the screen for three seconds. Participants were informed that they would later see a series of images and were instructed to classify each as ‘Seen’, ‘Unseen,’ or ‘Familiar.’ During this phase, the same set of 10 images was shown again in random order, and participants were required to make a classification for each one. These response options were included to ensure sustained attention throughout the Training session. Immediately after finishing the Training session, a capsule was administered that could be 200 mg of caffeine or a placebo and the participants left the laboratory. On the following day (Day 2), during the Testing session, participants received the instruction: ‘You are now going to see several groups of faces, each containing 6 photos. Each group could or could not contain one of the faces you watched before. If you recognize any of the faces, select the corresponding item (Each face in the lineup has a visible number ranging from 1 to 6). If you do not recognize any of the faces, select the item ‘I do not recognize any of the photos’. Participants assigned to the Present condition watched a lineup containing the original face along with five similar faces, whereas those in the Absent condition were presented with six faces similar to the original, without the original face included. There was no time limit for the Testing session elections. After making each choice, participants were asked about their level of confidence through the question: ‘How confident are you in your choice? Answer with a number within 1 and 100’.

Stimuli

On Day 1 (Training session), 10 human face images were generated using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)46. To create the Testing session lineups for Day 2, six new faces were generated for each lineup, and transitional images were created between the original face and each of these new faces. From these transitions, we selected the image representing a 50% blend of the original face and a new face, forming the final testing lineups. In the Present condition, the lineup included five transition-generated faces along with the original face from Day 1. In the Absent condition, only the six transition-generated faces were presented. Face image generation and manipulation were performed using a GAN-based architecture, specifically StyleGAN47, a variant optimized for the synthesis of realistic and controllable images. The implementation was integrated into an interactive web-based platform, enabling the generation of faces with modifiable attributes. This tool allowed for the creation of visual stimuli with controlled variability, ensuring consistency in face structure while exploring different phenotypic characteristics.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software. Post hoc power analysis were performed using G*Power348. An analysis of variance two-way ANOVA was conducted to assess the effect of caffeine (Caffeine vs. Placebo) and target condition (Present vs. Absent) on correct responses (hits/correct rejections) and false alarms. Further, to evaluate the relationship between the accuracy of the elections and the confidence attributed to them, CAC curves were performed. To calculate the value of the correct proportion corresponding to each confidence level (low 0–50%, medium 60–80%, or high 90–100%) the following formula was used: # Correct identifications/# Correct identifications + # Incorrect identifications49. Further, the levels of state anxiety, habitual daily caffeine consumption, body mass index, time awake at the beginning of the training session, and attentional performance (analyzed by comparing the number of face images identified as ‘Seen’ during encoding between groups) were analyzed using Student’s t-tests for both conditions. Additionally, an exploratory analysis was conducted within the Caffeine group participants, including both conditions, in which two subgroups were formed: Early and Late intake. This was based on recent studies showing that caffeine could negatively affect subsequent sleep even when consumed up to 8.8 h before bedtime38. This finding extends the previously suggested window of 6 h typically recommended to avoid sleep disruption50. Therefore, it was decided to control the timing of the Training session to ensure that proximity to bedtime was not influencing the results of the subsequent Testing session.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article is available at the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/15759113. The stimuli used are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Cappelletti, S., Daria, P., Sani, G. & Aromatario, M. Caffeine: cognitive and physical performance enhancer or psychoactive drug? Curr. Neuropharmacol. 13 (1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X13666141210215655 (2015).

Nehlig, A. Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer?. JAD 20(s1), S85–S94. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-091315 (2010).

Nehlig, A. & Debry, G. Effects of coffee on the central nervous system in coffee and health (ed. Debry, G.) 157–249 (Libbey, 1994).

Zhang, R. C. & Madan, C. R. How does caffeine influence memory? Drug, experimental, and demographic factors. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 131, 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.09.033 (2021).

Brunyé, T. T., Mahoney, C. R., Lieberman, H. R., Giles, G. E. & Taylor, H. A. Acute caffeine consumption enhances the executive control of visual attention in habitual consumers. Brain Cogn. 74 (3), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2010.07.006 (2010).

Giles, G. E., Mahoney, C. R., Brunyé, T. T., Taylor, H. A. & Kanarek, R. B. Caffeine and theanine exert opposite effects on attention under emotional arousal. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 95 (1), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2016-0498 (2017).

Davidson, R. A. & Smith, B. D. Caffeine and novelty: effects on electrodermal activity and performance. Physiol. Behav. 49 (6), 1169–1175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9384(91)90346-P (1991).

Tieges, Z., Snel, J., Kok, A. & Ridderinkhof, K. R. Caffeine does not modulate inhibitory control. Brain Cogn. 69 (2), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2008.08.001 (2009).

Castellano, C. Effects of caffeine on discrimination learning, consolidation, and learned behavior in mice. Psychopharmacol 48 (3), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00496858 (1976).

Cestari, V. & Castellano, C. Caffeine and cocaine interaction on memory consolidation in mice. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn Ther. 331 (1), 94–104 (1996).

Angelucci, M. E., Cesário, C., Hiroi, R. H., Rosalen, P. L. & Cunha, C. D. Effects of caffeine on learning and memory in rats tested in the Morris water maze. Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 35, 1201–1208. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-879X2002001000013 (2002).

Dias, A. L. A. et al. Post-learning caffeine administration improves ‘what-when’and ‘what-where’components of episodic-like memory in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 433, 113982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2022.113982 (2022).

Borota, D. et al. Post-study caffeine administration enhances memory consolidation in humans. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 201–203. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3623 (2014).

Hussain, S. J. & Cole, K. J. No enhancement of 24-hour visuomotor skill retention by post-practice caffeine administration. PloS One. 10 (6), e0129543. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129543 (2015).

Herz, R. S. Caffeine effects on mood and memory. Behav. Res. Ther. 37 (9), 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00190-9 (1999).

Mustard, J. A., Dews, L., Brugato, A., Dey, K. & Wright, G. A. Consumption of an acute dose of caffeine reduces acquisition but not memory in the honey bee. Behav. Brain Res. 232 (1), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2012.04.014 (2012).

Dance, C. J., Hole, G. & Simner, J. The role of visual imagery in face recognition and the construction of facial composites. Evid. Aphantasia Cortex. 167, 318–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2023.06.015 (2023).

Griffin, J. W., Bauer, R. & Scherf, K. S. A quantitative meta-analysis of face recognition deficits in autism: 40 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 147 (3), 268. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000310 (2021).

Mickes, L., Wilson, B. M. & Wixted, J. T. The cognitive science of eyewitness memory. TiCS https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2025.01.008 (2025).

Tredoux, C. G., Frowd, C., Vredeveldt, A. & Scott, K. Construction of facial composites from eyewitness memory. In Biomedical Visualisation The Art Vol. 13 149–190 (Philosophy and Science of Observation and Imaging. Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Flowe, H. D., Colloff, M. F., Kloft, L., Jores, T. & Stevens, L. M. Impact of alcohol and other drugs on eyewitness memory. In The Routledge International Handbook of Legal and Investigative Psychology 149–162 (Routledge, 2019).

Spielberger, C. D. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Mind Garden, 1983).

Green, P. J., Kirby, R. & Suls, J. The effects of caffeine on blood pressure and heart rate: a review. ABM 18 (3), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02883398 (1996).

James, J. E. & Gregg, M. E. Hemodynamic effects of dietary caffeine, sleep restriction, and laboratory stress. Psychophysiol 41 (6), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00248.x (2004).

Lovallo, W. R., Farag, N. H., Vincent, A. S., Thomas, T. L. & Wilson, M. F. Cortisol responses to mental stress, exercise, and meals following caffeine intake in men and women. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 83 (3), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2006.03.005 (2006).

Joëls, M., Pu, Z., Wiegert, O., Oitzl, M. S. & Krugers, H. J. Learning under stress: how does it work? TiCS 10 (4), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.002 (2006).

Schwabe, L., Wolf, O. T. & Oitzl, M. S. Memory formation under stress: quantity and quality. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 34 (4), 584–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.015 (2010).

Aust, F. & Stahl, C. The enhancing effect of 200 mg caffeine on mnemonic discrimination is at best small. Mem 28 (7), 858–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2020.1781899 (2020).

Mahoney, C. R., Brunye, T. T., Giles, G., Lieberman, H. R. & Taylor, H. A. Caffeine-induced physiological arousal accentuates global processing biases. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 99 (1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2011.03.024 (2011).

Segal, S. K., Stark, S. M., Kattan, D., Stark, C. E. & Yassa, M. A. Norepinephrine-mediated emotional arousal facilitates subsequent pattern separation. NLM 97 (4), 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2012.03.010 (2012).

Nakabayashi, K. & Liu, C. H. Development of holistic vs. featural processing in face recognition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 831. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00831 (2014).

Carter, A. J., O’Connor, W. T., Carter, M. J. & Ungerstedt, U. Caffeine enhances acetylcholine release in the hippocampus in vivo by a selective interaction with adenosine A1 receptors. JPET 273 (2), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3565(25)09521-7 (1995).

Leong, B. Q. Z., Estudillo, A. J. & Hussain Ismail, A. M. Holistic and featural processing’s link to face recognition varies by individual and task. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 16869. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44164-w (2023).

Langton, S. R. H., Law, A. S., Burton, A. M. & Schweinberger, S. R. Attention capture by faces. Cogn 107 (1), 330–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.07.012 (2008).

Robbins, R. & McKone, E. No face-like processing for objects-of-expertise in three behavioural tasks. Cogn 103 (1), 34–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.02.008 (2007).

Kamimori, G. H. et al. Caffeine improves reaction time, vigilance and logical reasoning during extended periods with restricted opportunities for sleep. Psychopharmacol 232, 2031–2042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-014-3834-5 (2015).

Smith, A. P., Rusted, J. M., Savory, M., Eaton-Williams, P. & Hall, S. R. The effects of caffeine, impulsivity and time of day on performance, mood and cardiovascular function. J. Psychopharmacol. 5 (2), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/026988119100500205 (1991).

Gardiner, C. et al. The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101764 (2023).

Leone, M. J., Sigman, M. & Golombek, D. A. Effects of lockdown on human sleep and chronotype during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Biol. 30 (16), R905–R931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.015 (2020).

Balas, B. & Pacella, J. Artificial faces are harder to remember. Comput. Hum. Behav. 52, 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.018 (2015).

Kätsyri, J. Those virtual people all look the same to me: Computer-rendered faces elicit a higher false alarm rate than real human faces in a recognition memory task. Front. Psychol. 9, 1362. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01362 (2018).

Steblay, N. M., Dysart, J. E. & Wells, G. L. Eyewitness accuracy rates in Police showup and lineup presentations: a meta-analytic comparison. LHB 27 (5), 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025596900713 (2003).

Instituto Nacional de la Yerba Mate. (s.f.). Yerba mate y salud. INYM. Retrieved [24/02/2025], of https://inym.org.ar/yerba-mate-y-salud.html

Ramallo, L. A., Smorcewski, M., Valdez, E. C., Paredes, A. M. & Schmalko, M. E. Contenido nutricional Del Extracto acuoso de La Yerba mate En Tres formas diferentes de Consumo. La. Alimentación Latinoam. 225, 48–52 (1998).

FDA. Al grano Cuánta cafeína es demasiada Administración de Alimentos y Medicamentos de los Estados Unidos. Retrieved [21/02/2025], Retrieved [21/02/2025], of. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/articulos-para-el-consumidor-en-espanol/al-grano-cuanta-cafeina-es-demasiada

Alqahtani, H., Kavakli-Thorne, M. & Kumar, G. Applications of generative adversarial networks (gans): an updated review. Arch. Computat Methods Eng. 28, 525–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-019-09388-y (2021).

Pawar, D. R. & Yannawar, P. Advancements and Applications of Generative Adversarial Networks: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.62148 (2024).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G* power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39 (2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007).

Mickes, L. Receiver operating characteristic analysis and confidence–accuracy characteristic analysis in investigations of system variables and estimator variables that affect eyewitness memory. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 4, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.01.003 (2015).

Drake, C., Roehrs, T., Shambroom, J. & Roth, T. Caffeine effects on sleep taken 0, 3, or 6 hours before going to bed. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 9 (11), 1195–1200. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3170 (2013).

Funding

Préstamo BID PICT 2020 Serie-A N° 02666 to C.F.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L. and C.F. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. C.L., A.L.LC and R.J. acquired the data. A.L.LC and R.G. were responsible for the medical screening of participants and administration of the experimental substance. C.L. performed the statistical analyses. C.L. made the graph art. C.L. and C.F. contributed by drafting the work. C.L. and C.F. contributed to revising it critically. C.F. was in charge of funding acquisition, project administration and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Use of large language models (LLMs)

During the manuscript preparation, a Large Language Model (ChatGPT, OpenAI 4.0) was used to assist with English language editing and grammar correction. The authors carefully reviewed and verified all LLM-assisted edits to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the final text.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leon, C.S., Lo Celso, A.L., Guajardo, R.A. et al. Caffeine reduces accuracy in face recognition memory consolidation. Sci Rep 15, 25722 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11737-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11737-w