Abstract

Ecological restoration has been widely regarded as an essential strategy to enhance carbon sequestration in ecologically fragile areas. However, the long-term sustainability and dynamics of carbon sequestration induced by afforestation remain uncertain, particularly in dryland river basins. Clarifying long-term carbon sequestration trends and understanding the impact of planted forests on these trends are crucial for ecological management and achieving carbon neutrality targets. In this study, we evaluated the dynamics of vegetation carbon sequestration and soil carbon storage in the Yellow River Basin (YRB) over the past two decades using annual Net Primary Production (NPP) and Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) datasets. Our results indicated that afforestation significantly enhanced NPP during the initial restoration phase (NPP increased by 34%), but subsequently NPP declined (NPP decreased by 10%), whereas SOC exhibited a modest increase with a gradually decreasing growth rate over time. Increased frequencies of extreme temperature and drought events negatively affected soil moisture availability and the sustained growth of planted forests. Furthermore, land-use transitions contributing to enhanced carbon sequestration and storage approached saturation, constrained by environmental limitations and cultivated-land protection policies. Given water-resource constraints, realizing future carbon sequestration benefits in dryland ecosystems requires more strategic vegetation spatial planning within ecological restoration initiatives. Our findings provide valuable insights for carbon management strategies in the YRB and similar dryland river basins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In response to ongoing global warming, the Paris Agreement was adopted at the United Nations Climate Conference in 2015, establishing international commitments to mitigate climate change1. China subsequently announced ambitious national targets to achieve peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, emphasizing the necessity of balancing anthropogenic carbon emissions with enhanced ecosystem carbon sinks2,3. Apart from direct emission reduction, carbon sequestration through ecological restoration has emerged as an indispensable strategy to achieve these climate objectives4,5.

Afforestation, as a primary ecological restoration measure, has been reported to significantly promote vegetation productivity and enhance carbon sequestration6,7,8. Dryland regions, which cover more than 40% of Earth’s terrestrial surface, are increasingly recognized for their substantial potential to serve as carbon sinks9,10,11,12. In China, dryland ecosystems and environmentally fragile areas have been prioritized for extensive ecological restoration13. Since the late 1990s, large-scale governmental restoration initiatives such as the Natural Forest Protection Project (NFPP) and the Grain-to-Green Program (GGP) have aimed to increase biodiversity, enhance vegetation cover, and strengthen ecosystem carbon sequestration through strategic land-use and land-cover transformations14,15,16.

Despite these efforts, the long-term sustainability of carbon sequestration induced by afforestation remains uncertain, particularly in dryland environments, due to increasing competition for limited water resources as vegetation expands17,18. Additionally, variations in land-use conversion pathways resulting from ecological restoration efforts further complicate predictions about carbon sequestration potentials19,20. Reliable predictions regarding future carbon sequestration capacity can only be achieved by analyzing long-term trends of carbon dynamics. However, the current lack of long-term, high-resolution data on forest carbon sinks and soil organic carbon (SOC) storage limits our understanding of the enduring impacts of afforestation on carbon sequestration in drylands21,22. Consequently, considerable uncertainty persists about whether ecological restoration-driven afforestation can sustain increased carbon storage over extended periods and significantly expand carbon sink capacities in drylands.

The Yellow River Basin (YRB) is a typical dryland region of China undergoing afforestation and vegetation restoration23,24,25. However, over half of the YRB receives annual precipitation of less than 400 mm with loose soil and relatively low fertility, constraining vegetation establishment and growth. Given these water limitations and decreasing land availability suitable for further vegetation restoration, vegetation expansion in the basin may already have approached its maximum potential. Additionally, long-term monitoring data on the growth quality and ecological performance of afforestation remain scarce. Furthermore, pronounced climatic and environmental differences among administrative divisions exacerbate uncertainties26,27.

This study focuses on the Yellow River Basin (YRB), a representative dryland ecosystem in China, to quantify the carbon dynamics associated with afforestation over the past two decades. Given the inherent spatial heterogeneity of ecological management practices and diverse environmental conditions (including vegetation types, precipitation, temperature, soil texture, and terrain), we examined spatial variations in carbon sequestration dynamics at a pixel scale. Additionally, we assessed differences in carbon sequestration responses resulting from various land-use transitions induced by ecological restoration initiatives. Specifically, two essential indicators—net primary productivity (NPP) and soil organic carbon (SOC) storage—were utilized to represent vegetation carbon fixation capacity and ecosystem carbon storage, respectively. By addressing these aspects, our findings aim to improve the understanding of carbon dynamics in afforested dryland river basins and provide detailed baseline information necessary for accurately estimating carbon sequestration potentials and informing future ecological restoration strategies and sustainable forest management.

Methodology

Study area

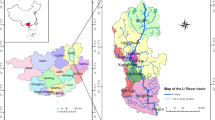

The Yellow River, an essential water resource for northern China, traverses nine provinces located predominantly in dryland areas (Fig. 1). Although accounting for only approximately 2% of China’s total river runoff, the Yellow River supports about 12% of the national population and provides irrigation water for roughly 15% of the nation’s cultivated land28. Historically, intensive agricultural practices have led to severe soil erosion across more than 70% of the Yellow River Basin (YRB), significantly compromising ecosystem functions29. Since the 1990s, the Chinese government has initiated numerous ecological restoration programs within the YRB, notably the Grain-for-Green Program (GFGP), to mitigate land degradation and enhance ecosystem resilience30. Grassland remains the dominant land type in the Yellow River Basin. Although these efforts have substantially increased forest and grassland coverage and improved regional carbon sequestration, the ecosystem conditions remain fragile and prone to degradation due primarily to limited water resources31.

Data preparation

The datasets used in this study include annual net primary productivity (NPP) and soil organic carbon (SOC) density products. Annual NPP data spanning 2001–2019 were derived by averaging the NPP products from the National Earth System Science Data Center (http://www.geodata.cn/data) and the MODIS MOD17A2 product (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/product_search/). These data have a spatial resolution of 500 m. Surface soil organic carbon density data (0–30 cm depth) covering the period 2001–2019 were also obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center, with a spatial resolution of 1 km32, (http://www.geodata.cn/data). Although theoretically, a longer time span would provide more accurate insights into the patterns of carbon sink changes, we ultimately selected nearly 20 years of data starting from 2001 after considering multiple factors, including resolution, accuracy, the timeline of ecological restoration projects in the YRB, and data availability (Updated to 2019).

Additionally, annual land-cover data (CLCD) for China covering the period 2000–2020 were acquired from Earth System Science Data (https://zenodo.org/record). This dataset has a spatial resolution of 30 m and includes nine land-cover classes: cropland, forest, shrubland, grassland, water bodies, snow and ice, barren land, impervious surfaces, and wetland. These land-cover data were used to assess the impacts of land-use changes on carbon dynamics. Temperature and precipitation datasets spanning 1990–2020 with a spatial resolution of 1 km were obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Scientific Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home). Soil moisture data were derived from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Soil Moisture Climate Change Initiative (CCI) project33. Potential evapotranspiration (ET) data were sourced from the National Earth System Science Data Center NPP Product (http://www.geodata.cn/data). Finally, soil texture data were obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD). These environmental datasets were used to analyze their influence on carbon sink dynamics throughout the study region.

Except for the land cover data, which retains a high resolution of 30 m for land cover transition analysis, all other datasets have been uniformly resampled to a 1 km resolution through registration and reprocessing. Given the minimal annual fluctuations in soil carbon, temporal scales of soil organ carbon data were standardized to the period 2000–2020.

Trends analysis by piecewise linear regression of NPP and SOC changes

Piecewise linear regression of NPP and SOC from 2001 to 2020

In the dryland regions of the YRB, land cover underwent substantial transformations around the year 2000, driven primarily by large-scale ecological restoration projects. However, the rate of vegetation expansion began to slow around 2010. Given the distinct temporal patterns of vegetation dynamics associated with human activities, it is expected that carbon sequestration trends within these ecosystems have also experienced stage-specific changes8. To capture these temporal dynamics, we employed a piecewise linear regression model to analyze the trends in ecosystem carbon sequestration within the YRB over the past two decades. This approach identifies turning points within the time-series data and applies linear regression separately to each identified segment. Specifically, the model determines the optimal turning points and corresponding regression slopes by minimizing the sum of squared residuals, thus providing an effective method for capturing temporal changes in carbon sequestration34.

In the equation: y represents the time series of vegetation coverage; t represents time (years);\({\beta\:}_{0}\), \({\beta\:}_{1}\), \({\beta\:}_{2}\), α are fitting parameters, where \({\beta\:}_{0}\) is the intercept of the fitting line, \({\beta\:}_{1}\) and \({\beta\:}_{1}\) + \({\beta\:}_{2}\) are the slopes for the first and second stages respectively, α is the estimated year of the trend change; ε represents random noise.

The spatial difference analysis of NPP and SOC changes caused by land use changes

Frequency histograms were employed to statistically analyze and visually represent trends in NPP and SOC changes across the study area. Specifically, we calculated the frequency distributions of the slope coefficients from the piecewise linear regression analysis: b1 (slope during the first stage) and b2 (slope during the second stage) for both NPP and SOC at pixel-level resolution. Both b1 and b2 are automatically generated through piecewise linear regression, with trend change detection determining the breakpoint while ensuring continuity between the two segments. To better illustrate the underlying patterns of these changes, we further applied Gaussian functions to fit the frequency histograms. Moreover, to assess the impacts of ecological restoration projects on land use and corresponding carbon dynamics, we compared the frequency distributions of b1 and b2 values within restoration regions against those of the entire YRB. Recognizing that the effects of specific land-use conversions on regional carbon sequestration require further exploration, we constructed a land-use transition matrix based on available land-cover data. Subsequently, we extracted and analyzed b1 and b2 slope values for pixels undergoing different land-use transitions, summarizing the results through frequency histogram statistics.

Analysis of factors affecting carbon sink capacity based on geographical detector

The geographical detector serves as an effective spatial statistics method based on spatial variation analysis of the geographical strata of variables, and it comprises as many as four modules, namely factor detector, interaction detector, ecological detector, and risk detector35. In order to explore the determinant power of the related factors and their interactive impact on carbon sink change, a geographical detector method was used in this study.

-

(1)

The factor detector quantifies the influences of factors on urban park use based on the q-statistic. Its formula is:

$$q = 1 - \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{h = 1}}^{L} N_{h} \sigma _{h}^{2} }}{{N\sigma ^{2} }}$$(2)Where q is the explanatory power of determinants associated with carbon sink change, h = 1, …, L are the stratification of y or factor x, that is, classification or partition; Nh and N stands respectively for the number of units in h and the whole region. \({{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{h}}^{2}\:\)and \({{\upsigma\:}}^{2}\) are the variance of units in h and the variance of y over the whole region, respectively. The q value ranges between 0 and 1, and the larger the q value is, the stronger the influence of factor x on y.

-

(2)

The interaction detector examines whether the factors (x1 and x2) have an interactive effect on carbon sink change. First, the q-statistic of factors x1 and x2 with respect to the carbon sink change were calculated and marked as q (x1) and q (x2). Then, the interactive q-statistic of factors x1 and x2 was calculated and marked as q (x1∩x1). The interactive relationship can be classified into five types (Weakened, nonlinear; Weakened, unique; Enhanced, bilinear; Independent; Enhanced, nonlinear) by comparing the interactive q-statistic of the two factor and the q-statistic of each of the two factors36. In this study, ecological detector and risk detector were not discussed because the carbon sink had been explained clearly by due to their weak relevance to this study.

Results and discussions

Spatial change characteristics of NPP and SOC in YRB

Over the past two decades, distinct spatial variations in NPP trends have occurred across the YRB (Fig. 2). In the lower and middle reaches, the growth rate of NPP has notably slowed, with many areas previously exhibiting rapid increases transitioning into pronounced declines (comparing slopes b1 and b2). In the central and northern regions, NPP initially showed a slight decline followed by a moderate recovery and accelerated growth. In contrast, continuous decreases in NPP were observed in the northernmost parts of the basin, although localized areas showed sustained increases. In the upper reaches, NPP trends were more variable, with some areas shifting from slight declines to rapid decreases, while others transitioned from slight increases to declining trends. Overall, declining trends were more prevalent throughout the basin.

Compared to the pronounced variability in NPP, changes in SOC were relatively subtle. Across much of the basin, SOC exhibited a generally slight increasing trend. However, the eastern part of the basin displayed a distinct shift, characterized by an initial SOC increase followed by a subsequent decline, which mirrored local NPP patterns. Significant declines in SOC were also observed in the upper reaches. In the middle reaches, SOC remained relatively stable or showed slight increases, while in limited areas of the northern basin, SOC experienced notably stronger increases.

Frequency histograms of the slopes derived from piecewise regression for NPP and SOC are presented in Fig. 3. During the initial period (b1), over half of the basin exhibited a positive NPP trend, with most pixels displaying slope values greater than zero. However, in the second period (b2), the frequency distribution of NPP slopes approached a normal distribution, indicating that NPP dynamics had transitioned from rapid growth to a relatively stable state characterized by nearly balanced areas of increase and decrease throughout the basin.

Similarly, the stability of SOC changes over the past two decades is also evident from the frequency histograms. Both the first and second stages of SOC slope distributions approximated normality across the entire basin. To better characterize these patterns, Gaussian functions were fitted to the SOC histograms (Butler, 1998), allowing direct comparison of SOC dynamics between the two periods. The results from Gaussian fitting indicated that SOC exhibited slight overall increases during both periods (\({x}_{b1}=0.047\:and\:{x}_{b2}=0.044\)). Nonetheless, the analysis revealed that a larger proportion of the basin experienced declining SOC trends during the second period relative to the first (\({x}_{b1}>{x}_{b2}\)).

Carbon changes characteristics in the planted forests restoration regions

Since the 1990s, a series of government-led ecological restoration programs have been implemented to expand forest and vegetation cover throughout the YRB, which have undoubtedly enhanced regional carbon sequestration capacity. However, the duration and sustainability of these carbon sequestration gains remain uncertain.

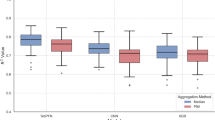

Our analysis (Fig. 4) revealed notable differences in carbon dynamics between restored ecological areas and the broader basin. In restoration areas, NPP rapidly increased during the initial restoration phase, reflecting vigorous vegetation recovery and growth driven by ecological conservation policies37. In the subsequent stage, NPP growth rates gradually stabilized, suggesting that vegetation productivity had reached a saturation point within restored ecosystems.

The transition in SOC between the two stages was less pronounced within ecological restoration regions, showing trends similar to those observed basin-wide. Nonetheless, SOC in restored areas exhibited a more rapid initial increase (\({x}_{b1}=0.088\)), followed by a substantial decline in growth rate during the second stage (\({x}_{b2}=0.006\)), falling even below the basin-wide average in the later phase. Although SOC changes were relatively modest compared to NPP, the differences between restoration and non-restoration areas across the entire basin still exhibited distinctive temporal patterns.

Over the past three decades, forest expansion within the YRB has largely been driven by plantation establishment, resulting in an increase of approximately 35,000 km² of planted forests (Fig. 5a). However, as indicated in Fig. 5b, annual NPP in planted forests shifted from increasing to declining trends within 15 years after planting in more than 80% of these areas, and in nearly half of these regions, declines began within 10 years. Considering that the primary tree species used for afforestation in the YRB, such as Robinia pseudoacacia and Pinus tabuliformis, typically mature around 50 years after planting38,39,40, the observed decline in carbon sequestration capacity occurred significantly earlier than expected. These findings suggest that planted forests in the YRB reach carbon sequestration saturation prematurely, raising concerns regarding their long-term effectiveness in regional carbon management strategies. Also, some researches demonstrated afforestation growth was limited in drylands due to water competition and insufficient soil nutrients41,42.

Carbon sink differences affected by the LUCC conversion

Significant land-use transformations have occurred within the YRB over the past two decades, primarily involving the conversion among forests, grasslands, croplands, and shrublands. Areas under ecological restoration policies promoting the conversion of cropland to forest and grassland have steadily declined over the last decade, whereas the conversion of grassland to forest has expanded. Concurrently, the availability of bare land suitable for vegetation restoration has approached saturation (Fig. 6).

As shown in Fig. 7, NPP trends following the conversion of cropland and grassland to forest exhibit an initial rapid increase, followed by a marked decline. This pattern aligns closely with the broader temporal trend observed for planted forests across the entire basin. Regarding SOC dynamics, the conversion from grassland to forest has only a limited impact, as indicated by the modest changes in slopes (b1 and b2). Conversely, cropland-to-forest transitions generally result in sustained increases in soil carbon storage across most converted areas.

In summary, the carbon sequestration capacity resulting from land-use-driven forest expansion in the YRB appears lower than previously anticipated. Given that most suitable bare land has already been utilized, conversions from sparse grasslands and croplands have become the dominant approach for afforestation. Regardless of whether the original land cover is grassland or cropland, NPP demonstrates an initial period of rapid growth, followed by a subsequent decline over multiple years. Cropland-to-forest conversion shows greater effectiveness in enhancing SOC stocks, with more than half of these areas experiencing continuous SOC accumulation. However, opportunities for cropland conversion are increasingly limited and have been steadily decreasing. Consequently, current land-use conversion patterns represent a key limitation to realizing the full carbon sequestration potential of ecological restoration in the basin. Furthermore, grassland-to-forest transitions offer comparatively limited benefits for carbon sequestration enhancement.

The carbon sink increase limitations resulting from environmental conditions

The influences of soil texture, soil moisture, air temperature, drought conditions, and their interactions on plantation carbon sequestration were investigated (Fig. 8). Model analyses indicated that although the individual impacts of these factors were relatively weak, their interactive effects were substantially stronger. Among these, soil moisture was identified as the primary individual factor controlling carbon sequestration dynamics. Furthermore, the interaction between soil sand content and temperature exerted a notably stronger influence on carbon sequestration than other factor interactions.

Detector of interactions among multiple factors based on Geographical detector model (SM_b: multi-year variation rate of soil moisture, sand: sand content in soil, maxtemp_mk: Mann-Kendall trend of long-term changes in annual maximum temperature, ET_b: multi-year variation rate of ET, dry_mk: the MK trends of annual maximum consecutive days of drought. ).

Previous studies have confirmed that the YRB is experiencing severe drought due to increases in potential evapotranspiration, resulting in reductions in soil moisture and subsequently limiting carbon sink capacity43,44. To better characterize drought impacts, two extreme climate indices were calculated: the annual maximum daily high temperature (MDHT) and the maximum consecutive drought days (MCDD). Mann-Kendall trend analysis was used to assess multi-decadal changes (2000–2020) in the two climate indicators. MK is commonly used for time series analysis in climate change45. As shown in Fig. 9, MDHT has increased steadily across most parts of the basin over the past several decades, with recent maximum daily temperatures exceeding 40 °C in some areas. Concurrently, MCDD exhibited a clear upward trend in the middle and upper reaches, with drought durations extending up to 180 days in recent years compared to historical averages of approximately 100 days. Existing research has demonstrated that drought leads to a decline or loss in NPP46,47. Therefore, extreme climate may serve as pivotal determinants of NPP change. Furthermore, numerous studies indicate that vegetation growth in the YRB has approached its ecological thresholds due to severe water limitations14,48,49. The intensified drought conditions driven by extreme climate events could further restrict vegetation productivity and thus limit the potential for future carbon sink enhancement.

Previous research commonly suggests that ecological restoration contributes positively to regional vegetation recovery and increased carbon sequestration potential50,51,52. However, the duration of monitoring in many of these studies was relatively short. Despite demonstrated benefits of ecological restoration in improving carbon sequestration within the YRB, these benefits have proven limited, particularly in ecologically vulnerable drylands53,54. Consequently, future ecological restoration strategies aimed at enhancing carbon sequestration in dryland ecosystems should carefully consider regional water availability constraints.

How to manage plantation effectively for ecosystem sustainability and climate mitigation

Large-scale afforestation efforts in dryland regions have shown limited long-term potential for enhancing carbon sequestration. Furthermore, extensive restoration activities may inadvertently exacerbate pressures such as soil desiccation in these water-limited ecosystems. To address these challenges, ecologically sound restoration strategies should involve careful assessment of local environmental conditions, sustained ecological monitoring, and the application of appropriate technologies. Specifically, selecting suitable indigenous or locally adapted plant species, combined with optimal management practices, is crucial to prevent soil moisture depletion and enhance ecosystem resilience. Moreover, since converting grasslands into forest plantations in dryland regions typically yields minimal improvements in carbon sequestration, restoration policies should consider prioritizing grassland recovery in areas with severe water scarcity. Restoration projects should avoid solely pursuing increases in vegetation cover or “greenness,” emphasizing instead scientifically informed spatial planning and management that effectively improves ecosystem services and ensures the long-term sustainability of dryland ecosystems.

Conclusions

This study examined the carbon sink dynamics influenced by ecological restoration and land-use changes in the YRB over the past two decades, using annual time-series datasets of Net Primary Productivity (NPP) and Soil Organic Carbon (SOC). Results from the piecewise linear regression analysis indicated that NPP exhibited an initial significant increase following restoration efforts, followed by a subsequent declining trend. Meanwhile, SOC demonstrated a subtle increasing trend, which gradually diminished over time, suggesting that the effectiveness of ecological restoration in enhancing carbon sequestration progressively weakens with the passage of time. Moreover, limited land availability, constraints posed by environmental conditions and water resources, and frequent disturbances from extreme climatic events negatively impacted the sustained accumulation of carbon in planted forests. Therefore, to effectively enhance and maintain long-term carbon sequestration in the YRB, it is crucial to consolidate ecological restoration achievements, optimize vegetation restoration patterns, and implement comprehensive post-restoration ecosystem management strategies. These insights can provide valuable guidance for regional ecological management and contribute meaningfully to the objectives outlined in the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Data availability

The data used in this paper is obtained from Earth System Science Data (https://www.geodata.cn/main/) and National Tibetan Plateau Scientific Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/).

References

Jenouvrier, S. et al. The Paris agreement objectives will likely halt future declines of emperor penguins. Glob. Change Biol. 26 (3), 1170–1184 (2020).

Dong, H. et al. Carbon neutrality commitment for china: From vision to action. Sustain. Sci. 17 (5), 1741–1755 (2022).

Zhou, C. et al. Institutional logic of carbon neutrality policies in china: what can we learn?. Energies 15 (12), 4391 (2022).

He, Y. & Ren, Y. Can carbon sink insurance and financial subsidies improve the carbon sequestration capacity of forestry?. J. Clean. Prod. 397, 136618 (2023).

Huang, Y., Li, Z. & Shi, M. Prediction of plant carbon sink potential in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China environment. Dev. Sustain. 26 (2), 3529–3556 (2024).

Han, D. et al. Large soil organic carbon increase due to improved agronomic management in the North China plain from 1980s to 2010s. Glob. Change Biol. 24 (3), 987–1000 (2018).

Zhou, J. et al. Impacts of ecological restoration projects on the ecosystem carbon storage of inland river basin in arid area, China. Ecol Indic. 118 106803 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Accelerated increase in vegetation carbon sequestration in China after 2010: A turning point resulting from climate and human interaction. Glob. Change Biol. 27 (22), 5848–5864 (2021).

Lal, R. Potential of desertification control to sequester carbon and mitigate the greenhouse effect. Clim. Change. 51 (1), 35–72 (2001).

Li, C. et al. Carbon stock and its responses to climate change in C entral A sia. Glob. Change Biol. 21 (5), 1951–1967 (2015).

Rotenberg, E. & Yakir, D. Contribution of semi-arid forests to the climate system. Science 327 (5964), 451–454 (2010).

Schimel, D. S. Drylands in the Earth System. Science. 327(5964), 418–419. (2010).

Cao, S. et al. Excessive reliance on afforestation in china’s arid and semi-arid regions: Lessons in ecological restoration. Earth Sci. Rev. 104 (4), 240–245 (2011).

Feng, X. et al. Revegetation in china’s loess plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Change. 6 (11), 1019– (2016).

Liu, T. et al. Environmental laws and ecological restoration projects enhancing ecosystem services in china: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manage. 327, 116810 (2023).

Song, W., Feng, Y. & Wang, Z. Ecological restoration programs dominate vegetation greening in China. Sci. Total Environ. 848 157729 (2022).

Rohatyn, S. et al. Limited climate change mitigation potential through forestation of the vast dryland regions. Science 377 (6613), 1436–1439 (2022).

Wei, X. et al. Assessment of the variation and influencing factors of vegetation NPP and carbon sink capacity under different natural conditions. Ecol Indic 138 108834 (2022).

Holmes, K. W. et al. Large-area spatially explicit estimates of tropical soil carbon stocks and response to land‐cover change. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 20(3). (2006).

Xin, Z., Qin, Y. & Yu, X. Spatial variability in soil organic carbon and its influencing factors in a hilly watershed of the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 137 660–669 (2016).

Ji, Y. et al. Long-term growth of temperate broadleaved forests no longer benefits soil C accumulation. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 42328 (2017).

Jia, X. et al. Carbon and water exchange over a temperate semi-arid shrubland during three years of contrasting precipitation and soil moisture patterns. Agr Forest Meteorol. 228 120–129 (2016).

Gao, G. et al. Effects of land-use patterns on soil carbon and nitrogen variations along revegetated hillslopes in the Chinese loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ 746 (2020).

Liang, Y., Hashimoto, S. & Liu, L. Integrated assessment of land-use/land-cover dynamics on carbon storage services in the loess plateau of China from 1995 to 2050. Ecol Indic. 120 (2021).

Tuo, D. et al. Effects of revegetation and precipitation gradient on soil carbon and nitrogen variations in deep profiles on the loess plateau of China. Sci. Total Environ. 626 399–411 (2018).

Lu, F., Ren, H. & Zhai, X. Regional differences and spatio-temporal convergence of environmental regulation efficiency in the yellow river basin, China. Front Ecol Evol. 11 1156981 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Spatial variation and influencing factors of the effectiveness of afforestation in China’s Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ 771 144904 (2021).

Li, X., Zhang, X. & Wang, S. Managing conflicts and equitability in hierarchical decision making for water resources planning under fuzzy uncertainty: A case study of yellow river. China J. Hydrol. Stud.. 38: p. 100963. (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Reduced sediment transport in the yellow river due to anthropogenic changes. Nat. Geosci. 9 (1), 38– (2016).

Feng, X. et al. Recent leveling off of vegetation greenness and primary production reveals the increasing soil water limitations on the greening earth. Sci. Bull. 66 (14), 1462–1471 (2021).

Hu, S. et al. Determination of the optimal ecological water conveyance volume for vegetation restoration in an arid inland river basin, Northwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 788 147775 (2021).

Xie, E. et al. Integration of a process-based model into the digital soil mapping improves the space-time soil organic carbon modelling in intensively human-impacted area. Geoderma. 409 115599 (2022).

Dorigo, W. et al. ESA CCI Soil Moisture for improved earth system understanding: State-of-the art and future directions. Remote Sens Environ. 203 185–215 (2017).

Pan, N. et al. Increasing global vegetation browning hidden in overall vegetation greening: Insights from time-varying trends. Remote Sens. Environ. 214 59–72 (2018).

Wang, J. F. & Hu, Y. Environmental health risk detection with GeogDetector. Environ Modell Softw 33 114–115 (2012).

Fan, Z. et al. A geographical detector study on factors influencing urban park use in nanjing, China. Urban For Urban Gree 59 126996 (2021).

Ma, R. et al. A modified habitat quality model to incorporate the effects of ecological restoration. Environ. Res. Lett. 17 (10), 104029 (2022).

Wang, J. J. et al. Carbon sequestration of mature black locust stands on the loess plateau, China. Plant. Soil. Environ. 61 (3), 116–121 (2015).

Liu, D. et al. The restoration age of Robinia pseudoacacia plantation impacts soil microbial biomass and microbial community structure in the loess Plateau. CATENA. 165 192–200 (2018).

Chen, L. et al. Age-related C:N:P stoichiometry in two plantation forests in the loess plateau of China. Ecol.Eng 120, 14–22 (2018).

Stavi, I. et al. Unexpected consequences of afforestation in degraded drylands: Divergent impacts on soil and vegetation. J. Environ. Manage. 345, 118703 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Nature-based framework for sustainable afforestation in global drylands under changing climate. Glob. Change Biol. 28 (7), 2202–2220 (2022).

Ren, Z. et al. Effects of aridification on soil total carbon pools in China’s drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 30(1). (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. The increasing contribution of potential evapotranspiration to severe droughts in the yellow river basin. J. Hydrol. 605. (2022).

Hamed, K. H. & Rao, A. R. A modified Mann–Kendall trend test for autocorrelated data. J. Hydrol. 204 (1–4), 182–196 (1998).

Li, J., Wang, Z. & Lai, C. Severe drought events inducing large decrease of net primary productivity in Mainland China during 1982–2015. Sci. Total Environ 703 135541 (2020).

Cao, D. et al. Projected increases in global terrestrial net primary productivity loss caused by drought under climate change. Earth’s Future 10(7): p. (2022). e2022EF002681.

Ge, F. et al. Afforestation reduced the deep profile soil water sustainability on the semiarid Loess Plateau. For. Ecol. Manag. 544. (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Regional development boundary of China’s Loess Plateau: Water limit and land shortage. Land Use Policy. 74: pp. 130–136. (2018).

Bryan, B. A. et al. China’s response to a national land-system sustainability emergency. Nature 559 (7713), 193–204 (2018).

Feng, X. et al. How ecological restoration alters ecosystem services: An analysis of carbon sequestration in China’s Loess Plateau . Sci. Rep 3 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multiple afforestation programs accelerate the greenness in the ‘three north’ region of China from 1982 to 2013. Ecol Indic. 61 404–412 (2016).

Vallejo, V. R. et al. Perspectives in dryland restoration: Approaches for climate change adaptation. New Forests. 43(5–6): pp. 561–579. (2012).

Zhang, D., Zuo, X. & Zang, C. Assessment of future potential carbon sequestration and water consumption in the construction area of the three-north shelterbelt programme in China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 303: p. 108377. (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42201339), Gansu Provincial Key R&D Program for Ecological Civilization Development (24YFFA051). Thanks to the research project of Peking University-Ordos Carbon Neutrality Joint Laboratory, and thanks to the Ordos Carbon Neutrality Research Institute for providing technical support. We also would like to thank the editor and the reviewers for valuable suggestions and comments to improve the previous version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yingying Yang carried out most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Huawei Wan gave suggestions about the method. Yihe Lü provided the main frame and modified the writing. Yunlong Zhang offered help for modifying the original manuscript. Haowei Duan modified the writing. Xuwei Sun provided funding support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Duan, H., Wan, H. et al. Analysis of 20 years of monitoring data reveals insufficient carbon sequestration potential of planted forests in dryland regions. Sci Rep 15, 26973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11740-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11740-1