Abstract

Multimodal sentiment analysis significantly improves sentiment classification performance by integrating cross-modal emotional cues. However, existing methods still face challenges in key issues such as modal distribution differences, cross-modal interaction efficiency, and contextual correlation modeling. To address these issues, this paper proposes an Adaptive Multimodal Transformer based on Exchanging (AMTE) model, which employs an exchange fusion mechanism. When the local emotional features of one modality are insufficient, AMTE enhances them with the global features of another modality, thus bridging cross-modal semantic differences while retaining modality specificity, achieving efficient fusion. AMTE’s multi-scale hierarchical fusion mechanism constructs an adaptive hyper-modal representation, effectively reducing the distribution differences between modalities. In the cross-modal exchange fusion stage, the language modality serves as the dominant modality, deeply fusing with the hyper-modal representation and combining contextual information for sentiment prediction. Experimental results show that AMTE achieves excellent performance, with binary sentiment classification accuracies of 89.18%, 88.28%, and 81.84% on the public datasets CMU-MOSI, CMU-MOSEI, and CH-SIMS, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing demand for emotion understanding in social media and human-computer interaction scenarios, multimodal sentiment analysis has become an important research direction in natural language processing1. Existing research has made significant progress in improving sentiment classification performance by integrating emotional cues from text, speech, and visual modalities. However, current methods still have some shortcomings in addressing key issues such as modal distribution differences2, inefficient cross-modal interaction3, and contextual correlation analysis4. To address these challenges, this chapter proposes a multimodal sentiment analysis model based on adaptive hyper-modal dynamic exchange to provide new methods for subsequent research.

Firstly, most existing methods fail to adequately address the problem of distribution differences between modalities5. The features of different modalities are often distributed in heterogeneous high-dimensional spaces, making effective fusion difficult. This difference stems from the heterogeneous physical characteristics of each modality and the feature extraction methods. In terms of physical characteristics, audio signals are continuous signals transmitted by sound waves, with physical characteristics such as frequency and amplitude; image signals are two-dimensional spatial data perceived by vision, including features such as color, contrast, and resolution; text signals are composed of discrete language units, with attributes such as sentence length and grammatical structure. In terms of extraction methods, text modality is usually mapped to a high-dimensional discrete space through word vectors, while speech and visual modalities rely on spectral or image feature extraction to map to a continuous space. While some approaches attempt to mitigate these differences through alignment mechanisms (You et al.6) or attention mechanisms (Zhang et al.7) designed to focus on the most emotionally salient information within each modality, these strategies have limitations. Alignment processes can be highly sensitive to noise, particularly in less controlled environments like social media videos, where modal noise can significantly degrade alignment quality. Similarly, when modal information is redundant or conflicting, attention mechanisms may inadvertently guide the model to focus on less relevant modalities or features (Tsai et al.8). Consequently, this inherent distribution difference often introduces redundant and conflicting information, ultimately reducing the model’s ability to effectively capture and integrate emotion-related features across modalities.

Secondly, mainstream multimodal fusion methods suffer from inefficient cross-modal interaction and feature imbalance3. Specifically, traditional feature-level fusion strategies (such as weighted average, concatenation, etc.) only achieve shallow feature aggregation and lack deep information interaction between modalities. This fusion method based on simple operations fails to effectively capture the complex relationships between modalities, resulting in the loss of potential emotional information. Moreover, although cross-modal attention mechanisms can establish associations between modalities, attention modules may over-focus on cross-modal features unrelated to emotion (such as the accidental association between visual background and speech noise), introducing non-emotional information interference. Furthermore, although alignment-based fusion methods strengthen the consistency of modal representation space through subtask constraints (Han et al.9) or joint loss functions (Hazrika et al.10), this alignment may ignore the unique features within modalities. Existing methods struggle to establish an effective balance between global interaction and local feature retention, resulting in low efficiency of interaction between modalities.

In addition, current research has not paid enough attention to the continuous nature of multimodal emotional expression, and the emotional state at the current moment is often affected by the context of the previous moment4. Taking monologue as an example, the speaker’s emotional attitude may be related to previous dialogues through logical relationships such as rhetorical questions, progressions, or turns. If only the current statement is analyzed, the model may find it difficult to capture emotional meanings such as “irony” that depend on historical context. For example, when semantically ambiguous adjectives appear in the current text, the emotional tone established in the historical context can help the model make more accurate emotional classifications. Wu et al.11 demonstrated that incorporating contextual information significantly improves sentiment recognition performance in their Multimodal Multi-loss Fusion Network, highlighting the essential role of context in multimodal sentiment analysis.

To address the above shortcomings, this paper proposes an Adaptive Multimodal Transformer based on Exchanging (AMTE) model for multimodal sentiment analysis based on exchange fusion. In AMTE, firstly, the features of each modality are extracted and uniformly represented through Transformer to remove redundant information. Then, in the adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module, the language features are modeled in multiple layers through the Transformer layer to obtain low, medium, and high-scale language features. The multi-level features of the language modality are used to exchange and fuse with the visual and audio modalities respectively, supplementing the lack of emotional information in the visual and audio modalities, realizing the gradual fusion of information between modalities, and generating an adaptive hyper-modal representation that integrates multimodal information, effectively reducing the difference in multimodal feature distribution. The exchange fusion mechanism selectively replaces tokens with low emotional attention scores, while the remaining tokens retain the original modality’s features. This avoids the loss of original information when realizing information interaction between modalities and maintains the expressive ability within modalities. Then, in the cross-modal exchange fusion stage, the language modality and the hyper-modal representation are deeply integrated through the exchange mechanism to generate a joint emotional feature-rich representation that takes into account the characteristics within and between modalities. Finally, the classifier outputs emotional prediction results in conjunction with contextual information. This process effectively solves the problems of information conflict and redundancy in multimodality, while fully exploring the complementarity and contextual emotion between modalities. The main contributions of AMTE are as follows:

-

(1)

An adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module is designed. By constructing multi-scale hierarchical fusion, the language modality is decomposed into semantic representations of different granularities, and the feature exchange of visual and speech modalities is dominated by a threshold mechanism, generating an adaptive hyper-modal representation, unifying multimodal representations, and enhancing the complementarity of cross-modal information.

-

(2)

The exchange-based method is innovatively extended from traditional single visual modality fusion to text-image-speech three-modality fusion for dynamic feature compensation. When the emotional proportion of local features of a certain modality is insufficient, it is enhanced by the global features of another modality, achieving cross-modal semantic bridging while retaining modal specificity. Ensure that the final output can maintain the uniqueness of various modalities while fully exploring the correlation and similarity between them, thereby achieving higher interaction efficiency.

-

(3)

A context extraction module is innovatively introduced, which utilizes the high-level semantic representation of historical context to improve the model’s ability to parse complex emotions.

Related works

Multimodal fusion methods

In multimodal sentiment analysis, the accuracy of sentiment classification is improved by fusing information from multiple modalities, such as text, speech, and images. Since emotions are expressed in multiple dimensions, using different modalities can capture emotional features from different perspectives, helping to build a more comprehensive emotional model. Multimodal feature fusion is a key step in achieving this goal. In this process, multimodal features can be simply combined, or the potential emotional relationships between modalities can be fully considered. Currently, multimodal fusion methods can be divided into three types according to the fusion stage: feature-level fusion, decision-level fusion, and hybrid fusion12.

Feature-level fusion

Feature-level fusion, also known as early fusion, has a core idea of reorganizing the features of each modality into new feature representations through concatenation, weighted operations, or projections before inputting them into the model. By directly combining the features of different modalities (Poria et al.13; Pérez-Rosas et al.14), multimodal emotional information can be utilized simultaneously in subsequent models. Although feature-level fusion has studied the interactions between different modalities, the direct fusion of them at the initial stage may lead to information loss or mutual interference, masking key features due to the respective feature spaces and information expression methods of different modalities. In addition, early fusion leads to a sharp increase in the dimensionality of the joint feature vector, which brings about increased computational complexity and the risk of overfitting.

Decision-level fusion

Decision-level fusion, also known as late fusion, usually establishes different models for multiple modalities, performs sentiment analysis on each modality, and then incorporates single-modal sentiment decisions into the final decision. The incorporation methods include weighted sums (Zadeh et al.15; Morvant et al.16), majority voting, and so on. Through this mechanism, the model can make decisions based on the correlation and weights between different modalities. The advantage of decision-level fusion is that the data of each modality can be processed independently, retaining their respective features and characteristics, which is suitable for dealing with situations where the differences between modalities are large. However, it cannot make full use of the interrelationships between different modalities, and may lose potential cross-modal information. At the same time, it needs to model and train each modality separately, and the computational overhead is relatively large.

Hybrid fusion

Different from feature-level fusion and decision-level fusion, hybrid fusion no longer emphasizes the stage of the fusion process, but is committed to fusing multimodal data features at different levels. It can be further subdivided into tensor-based fusion methods, graph-based fusion methods, and attention-based fusion methods, etc.

Tensor-based fusion methods combine and interact features from different modalities by constructing and manipulating high-dimensional tensors (Zadeh et al.17; Liu et al.18). This method can capture high-order associations and complex dependencies between multimodal features, enhancing the expressiveness of multimodal data. However, this method usually projects low-dimensional features into high-dimensional space, resulting in a sharp increase in feature dimensions. As the number of low-dimensional features or the size of each feature dimension increases, the feature dimension after mapping to high-dimensional space also increases significantly, thereby increasing the training difficulty of the model and limiting its scalability.

In multimodal sentiment analysis, graph structures can effectively represent the interrelationships between different modalities and within modalities. For example, nodes can represent features from different modalities (such as text, speech, vision, etc.), and edges can represent the dependencies or similarities between these features (Xiao et al.19). Lin et al.20 proposed HGraph-CL, a hierarchical graph contrastive learning framework that constructs syntax-aware and sequential graphs for each modality, and further integrates them into a unified inter-modal graph to effectively capture sentiment cues. Zhao et al.21proposed a Heterogeneous Fusion Network based on Graph Convolution (HFNGC), which effectively mitigates modality heterogeneity and semantic misalignment by leveraging a convolutional aggregation mechanism and graph-based feature learning. Tang et al.22 proposed MECG, a graph convolution-based framework designed specifically to address the issue of unbalanced multimodal sentiment representation. By introducing a modality enhancement module and constructing text-driven multimodal graphs, MECG effectively enriches visual and acoustic features under the guidance of textual input, and performs fusion through graph convolutional operations to obtain semantically aligned sentiment embeddings across modalities. Through the graph structure, the model can fully fuse emotional information from different modalities and different speakers. However, when dealing with long sequences or high-dimensional features, the number of nodes in graph-based fusion methods may increase exponentially, which affects the model’s training efficiency and inference speed.

Attention-based fusion methods selectively combine information from different modalities by introducing attention mechanisms, thereby capturing deeper-level correlations between different modalities. Currently, a common approach is to combine features of different modalities in pairs (Tsai et al.8) and use cross-attention mechanisms to weight and mark important regions of each modality. Quan et al.23 proposed a Text-oriented Cross-Attention Network (TCAN) that emphasizes the semantic primacy of the textual modality in multimodal sentiment analysis. By employing a dual bi-modal fusion strategy–specifically, text-visual and text-acoustic interactions–and incorporating a gated control mechanism, TCAN effectively enhances cross-modal representation while mitigating the influence of redundant and noisy information. Wu et al.24 propose a novel perspective by modeling sentiment as a form of cognitive-emotional reasoning, where attention mechanisms are employed not only for modality fusion but also to emulate human-like emotional inference across modalities. Their approach leverages both inter-modal and intra-modal attention to dynamically weigh affective cues, thereby enriching the semantic representation of multimodal data. A potential drawback is that attention mechanisms might overemphasize redundant information shared across modalities (e.g., both text and image describing an object unrelated to the sentiment) and can be computationally intensive.

Methods

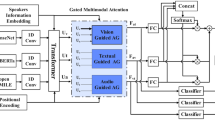

The structure of AMTE is shown in Figure 1. First, to obtain better multimodal emotional representations and filter redundant information, each modality input is passed through a Transformer to obtain unified features. Then, in the adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module, the visual and audio modalities are supplemented with emotional information layer by layer from different levels of the language modality, eventually obtaining an adaptive hyper-modal representation that integrates multimodal information and has a unified distribution. Next, the hyper-modal representation and language modality features are jointly modeled through the cross-modal exchange fusion layer. Finally, contextual language features are combined and input into the classifier to obtain sentiment analysis results.

Modality embedding module

This paper employs the RoBERTa25 model for text feature extraction. For images and audio, OpenFace26 and Librosa27/Opensmile28 are used as feature extractors, respectively. This module is designed for feature extraction and noise reduction from raw multimodal input. Let the input modality sequence be \(U_m\), where \(m \in \left\{ {c,t,v,a} \right\}\), with c being the text from the previous time step, t being the text modality at the current time step, v being the visual modality, and a being the audio modality. First, the modalities are mapped to a unified dimensional space through a linear projection layer:

where \(U_m^0\in \mathbb {R}^{N\times d}\). Subsequently, a learnable low-dimensional embedding vector \(H_m^0\in \mathbb {R}^{k\times d}\) is introduced and fused with the projected modality sequence through concatenation to obtain the embedded features:

where concat denotes the concatenation operation, \(E_m^0\) is a Transformer layer, d is the feature dimension, N is the number of time steps, and k is a hyperparameter. Positional encoding is also added when passing through the Transformer layer. Through this embedding module, redundant information is removed, irrelevant features in each modality input are reduced, and the difficulty of cross-modal alignment is decreased.

This module references the input processing mechanism and modality embedding idea of the Vision Transformer (ViT)29. ViT divides an image into several fixed-size patches and maps each patch to a low-dimensional vector space through a linear transformation. These vectors, along with positional encoding, form the input sequence for the Transformer. This process unifies the original high-dimensional, structurally complex image data into a sequence with consistent structure and clear semantic representation.

To suppress redundant information and condense features, ViT adds an initialized token before all patches (similar to the low-dimensional embedding vector \(H_m^0\) in this module). Through the self-attention mechanism, this token continuously aggregates information from all patches in each layer, ultimately forming a global semantic representation of the entire image. This mechanism not only achieves information fusion but also effectively suppresses redundant content in the image. Since original images often contain a large amount of non-target regions such as edges and backgrounds, direct modeling can often introduce interference. However, ViT, through learning attention weights, adaptively highlights key regions and ignores irrelevant information, thereby improving the compactness and discriminative power of the semantic representation.

Multi-scale language feature extraction module

To obtain high-quality and compact emotional representations from the language modality, this paper uses 2 Transformer layers to extract medium and high-scale language features from \(H_t^1\). Different levels of features contain diverse information from local syntax to global semantics. The processing is as follows:

where \(i\in \left\{ 2,3\right\}\), and \(E_t^i\) is the i-th layer Transformer layer.

Hyper-modal exchange fusion module

First, initialize an adaptively updated hyper-modal representation \(H_{hyper}^0\), and then combine the language modality, visual modality, and auditory modality to update the adaptive hyper-modal representation. The hyper-modal representation reduces the inconsistency of information between modalities, making the model more stable in processing multimodal input and improving the accuracy and generalization ability of sentiment analysis. The structure is shown in Figure 2, and the specific process is as follows:

In the Transformer architecture, the 0th token (often a special token like [CLS] or an initialized learnable embedding) serves as a crucial anchor for aggregating sequence-level semantics. Its self-attention weights, specifically the attention scores it assigns to other tokens in the sequence (\(A_m[0, j]\) for \(j> 0\)), implicitly quantify the relevance or contribution of each local feature (token j) to the overall global context captured by the 0th token. The exchange mechanism leverages this principle: it interprets the attention score \(A_m[0, j]\) as an indicator of the j-th token’s emotional salience or contribution within its modality. When this score falls below a dynamically determined threshold \(\theta\), it suggests that the local feature represented by token j provides insufficient emotional information relative to the global context. This threshold \(\theta\) is determined based on a hyperparameter \(\phi \in [0, 1]\), which specifies the proportion of tokens with the lowest attention scores (excluding the 0th token) to be selected for exchange. Specifically, \(\theta\) corresponds to the attention score at the \(\phi\)-th percentile of the sorted scores \(A_m[0, j]\) for \(j> 0\). To address this, the mechanism performs cross-modal supplementation by replacing the feature vector of this low-contribution token \(\hat{H}_m[j]\) with an enhanced representation. This enhanced representation is formed by adding the original token’s feature \(\hat{H}_m[j]\) to the averaged feature vector derived from the corresponding scale of the language modality (\(\frac{1}{n}\sum _{i=0}^{n-1} H_t^u[i]\)). Crucially, the 0th token itself is never replaced, preserving it as a stable anchor point for grounding the cross-modal interactions and maintaining the integrity of the global representation derived from the original modality. This targeted exchange enhances modality representations by infusing complementary information precisely where local cues are weak, while retaining strong local features and the overall sequence structure.

In each exchange layer, the attention weights and outputs of the audio and visual modalities are calculated through multi-head attention, respectively:

Then, cross-modal exchange is performed. Taking the attention score of the 0th token of each modality as a reference, tokens that contribute less to the global context are selected to exchange with the language modality, that is, tokens with smaller attention scores \(A_m\left[ 0,j\right]\) are selected for exchange. For each selected token, its feature vector is added with the average value of the medium and high-scale features of the text to achieve information supplementation.

Conditional replacement is performed according to the first token attention score \(\alpha _j=A_m\left[ 0,j\right]\):

where \(m\in \left\{ v,a\right\}\), n is the sequence length, u represents the u-th layer, and \(0<j<n\).

Then update \(H_{hyper}^u\):

where \(\oplus\) represents feature concatenation, and \(W_g^u\) is a learnable parameter.

Context extraction module

Contextual information in language expression is crucial for understanding human emotions and intentions. Therefore, this paper inputs the previous moment’s text of the current text as additional contextual features into the model. The model structure is the same as the multi-scale language feature extraction module, and the two-layer Transformer can obtain efficient historical emotional representations. The processing flow is as follows:

where \(i\in \left\{ 2,3\right\}\), and \(E_c^i\) is the Transformer layer.

Cross-modal exchange fusion module

The language modality feature \(H_l^u\) interacts with the hyper-modal representation \(H_{hyper}^3\), which can effectively capture emotional information and achieve fine-grained token-level interaction. The cross-modal exchange fusion layer structure is shown in Figure 3. The hyper-modal representation \(H_{hyper}^3\) and the language modality feature \(H_l^u\) are updated by exchange fusion to update \(H_l^u\):

where \(u\in \left\{ 1,2\right\}\), u represents the u-th layer, \(0<j<n\), and \(H_l^1\) is equal to \(H_t^3\).

Sentiment prediction module

Inputting the language modality feature \(H_l^3\) and the context feature \(H_c^3\) into the classifier can obtain the sentiment prediction result:

Since it is a regression task, the task loss can be calculated by the mean square loss:

where \(N_b\) is the total number of samples.

Experiments

Datasets

This study selected three representative multimodal sentiment analysis benchmark datasets for experimental verification: MOSI30, MOSEI31, and SIMS32.

MOSI dataset contains movie review video clips posted by 89 speakers on the YouTube platform. Among these 89 people, 48 are male and 41 are female, with an age range of 20 to 30 years old. The dataset has a total of 2199 independent clips, with an average clip length of about 4.8 seconds. The data covers three modalities: text, visual, and audio. The sentiment labels range from −3 (strongly negative) to +3 (strongly positive), and there are also seven categories of sentiment classification labels.

MOSEI is an expanded version of MOSI, which extends the sample size to 23,453 opinion slices, including 1,000 different speakers. The dataset contains 3,228 videos from 250 different topics, covering a variety of themes, such as reviews, debates, and consultations. The gender distribution in the dataset is 57% male and 43% female. In addition to basic sentiment polarity annotations, this dataset introduces 7 emotion categories, supporting multi-label classification tasks.

CH-SIMS is a Chinese multimodal sentiment analysis dataset containing 2,281 video clips. The videos in the dataset come from movies, TV series, and variety shows. The dataset considers the diversity of real-world scenarios, with clips featuring different actors, different age groups, and different emotional expressions. Each video clip includes not only unified multimodal sentiment labels, but also sentiment annotations for text, audio, and visual modalities, respectively. The sentiment labels are divided into five categories: negative, relatively negative, neutral, relatively positive, and positive, with each category corresponding to a different sentiment value.

Evaluation criteria

In this experiment, the evaluation metrics employed are binary classification accuracy (Acc2), F1-score (F1), Pearson correlation coefficient (Corr), and mean absolute error (MAE).

Baselines

To validate the model’s performance, this paper conducted comparative experiments with several excellent models under the MMSA framework. The specific models compared include: MFN15, EF-LSTM33, TFN17, LMF18, Mult8, Self-MM34, MISA10, BBFN35, EMT-DLFR24, CENet36, TETFN37, UniMse38, HCIL39 and MTAMW40.

Performance comparison

Table 1 and Table 2 present the experimental results of the baseline methods and the proposed approach in this section on the MOSI, MOSEI, and CH-SIMS datasets.

Experiments have demonstrated that AMTE significantly outperforms other models on the MOSEI dataset across all metrics, and also exceeds other methods on the MOSI dataset in most metrics. AMTE achieved binary classification accuracies of 88.28% and 89.18% on these two datasets, respectively, representing improvements of 0.62% and 2.28% compared to the best baseline model, UniMSE. Furthermore, on the more complex SIMS dataset, AMTE’s binary classification accuracy and F1 score surpassed other baseline models, with a 0.66% increase in binary classification accuracy compared to the second-best baseline model, TETFN. The results from these four datasets indicate that AMTE’s adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module significantly reduces distribution differences between modalities and further improves the accuracy of sentiment prediction through the cross-modal fusion module. By reducing redundancy, mitigating heterogeneity, and enhancing the ability to supplement emotional information, AMTE exhibits strong advantages in handling complex emotional expressions.

Ablation study and analysis

Effects of different fusion methods

AMTE employs an exchange-based multimodal fusion approach. To validate its effectiveness, this section conducted comparative experiments on the MOSEI and SIMS datasets using different fusion methods, with the results shown in Table 3. Specifically, we compared our proposed cross-modal exchange fusion with several alternative strategies for integrating the language modality features and the hyper-modal representation. These include: (1) Addition, which performs element-wise summation of the two feature vectors; (2) Concatenation, which joins the two feature vectors end-to-end; (3) Cross-modal Attention, where the language modality features serve as the Query (Q), and the hyper-modal representation acts as both Key (K) and Value (V) within a standard attention mechanism; and (4) Low-rank Multimodal Fusion (LMF)18, a representative tensor-based fusion technique. LMF is included in the comparison as it is a widely recognized method capable of capturing complex inter-modal interactions through low-rank tensor decomposition, providing a strong baseline for evaluating advanced fusion strategies like ours. These comparisons aim to demonstrate the relative advantages of the exchange mechanism over simpler fusion operations and established attention/tensor-based approaches in this specific fusion context. It is important to note that this ablation study focuses on the fusion mechanism within the Cross-Modal Exchange Fusion Module, where the final integration of language and hyper-modal information occurs before sentiment prediction.

From Table 3, it is evident that cross-modal exchange fusion excels in key metrics such as binary classification accuracy, F1 score, and MAE, particularly in Acc2, which outperforms other fusion methods. Compared to the second-best cross-modal attention method, cross-modal exchange fusion’s Acc2 leads by 0.33% and 1.32% on MOSEI and SIMS, respectively, demonstrating its superior performance. The addition-based method may lose some modality-specific information during fusion, resulting in lower Acc2 and higher MAE compared to cross-modal exchange fusion, indicating poor performance. The cross-modal attention method’s metrics are close to those of our cross-modal exchange fusion, but still fall short, suggesting that cross-modal exchange fusion ensures deep information exchange between modalities through a meticulous layer-by-layer replacement mechanism during multi-level fusion, providing more accurate sentiment prediction results.

Further analysis reveals the limitations of alternative methods compared to exchange fusion. The concatenation-based approach, for instance, fails to fully leverage the complementarity of cross-modal features; when text descriptions are semantically ambiguous, the potential supplementary role of visual and auditory features is difficult to activate through simple concatenation. While the cross-modal attention mechanism optimizes feature interaction via dynamic weight allocation, its performance in binary classification accuracy, F1 score, and correlation metrics does not reach the level of exchange fusion. This might stem from the attention mechanism’s susceptibility to generating spurious correlations under noisy conditions. In contrast, the proposed exchange fusion mechanism achieves more refined information compensation. Firstly, the threshold-based filtering using first-token attention weights refines the granularity of modal interaction from the sequence level to the token level. This allows for the adaptive identification of feature segments with lower emotional contribution within each modality and targeted supplementation with features from other modalities. Secondly, the design involving conditional residual connections mitigates potential semantic disruptions caused by feature replacement, thereby preserving modality-specific characteristics while facilitating effective fusion.

Effects of different modalities

To explore the differences in emotional representation capabilities between different modalities, this section conducted experiments on the MOSEI and SIMS datasets, with the results shown in Table 4. Specifically, we evaluated several variants of the AMTE model: (1) w/o audio, where the audio modality is entirely removed from the model; (2) w/o vision, where the visual modality is removed; (3) Audio-dominant fusion, where the roles of the text and audio modalities are swapped throughout the fusion process, making audio the primary modality guiding the integration; (4) Visual-dominant fusion, similar to the audio-dominant setup, but with the visual modality taking the leading role in fusion; and (5) Hyper-modal representation-dominant fusion, where in the final Cross-Modal Exchange Fusion Module, the hyper-modal representation, rather than the language modality, serves as the dominant feature stream guiding the exchange fusion. These ablation studies aim to quantify the contribution of each modality and validate the design choice of using text as the dominant modality in AMTE’s fusion architecture.

On the MOSEI and SIMS datasets, the absence of audio and visual modalities leads to a decline in model performance, with a more significant drop when the visual modality is missing, especially in accuracy (Acc2) and F1 score. The experiments demonstrate that both audio and visual modalities provide valuable emotional cues in multimodal sentiment analysis, and removing any of them affects the model’s overall performance. The visual modality’s contribution to sentiment analysis tasks is more significant than that of the audio modality. Meanwhile, AMTE, by combining all modalities, leverages the complementary advantages of each modality, enhancing the precision of sentiment analysis.

Additionally, to validate the feasibility of text-dominant multimodal fusion, this section conducted comparative experiments on the MOSEI and SIMS datasets with audio, visual, and hyper-modal representation-dominant fusion, with the results shown in Table 4.

The experimental results show that performance declines when audio modality dominates fusion. In contrast, the model performs relatively well when visual modality dominates fusion. This further indicates that the visual modality’s emotional representation capability is stronger than that of the audio modality.

The text-dominant AMTE model achieves the best results in Acc2 and F1 score on both datasets, with improvements of 1.1% and 1.13% (MOSEI) and 1.97% and 1.96% (SIMS) compared to the second-best hyper-modal representation-dominant fusion. This suggests that while hyper-modal representation can effectively fuse information from different modalities, the language modality can more clearly convey emotional information and incorporate historical semantics, thereby enhancing the model’s overall performance. Comparing text-dominant fusion with other modality-dominant fusion verifies that text-dominant fusion exhibits optimal performance on both datasets.

Effects of different modules

In sentiment classification tasks, AMTE’s adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module, context learning module, and cross-modal exchange fusion module all play crucial roles. To investigate the impact of different modules, this section conducted comparative experiments on the MOSEI and SIMS datasets, with the results shown in Table 5.

Removing the adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module results in the most significant performance decline, especially in accuracy and F1 score, with decreases of 1.19% and 1.15% on MOSEI, and 4.6% and 4.6% on the SIMS dataset, respectively. Removing the cross-modal exchange fusion module also leads to a decline in all metrics, indicating that this module deeply integrates the text modality and hyper-modal representation, forming a unified multimodal representation and improving overall performance. The adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module’s impact is the most significant, as it optimizes the exchange and integration of audio and visual modality information, unifies distribution differences between modalities, and effectively enhances the accuracy of sentiment analysis. Removing the context module on the MOSEI dataset results in a slight performance decline, revealing that historical context contributes to the granularity and overall performance of sentiment analysis.

Visualization of different representations

To study the effectiveness of the adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module, this section visualized the adaptive hyper-modal representation \(H_{hyper}^3\), audio representation \(H_a^1\), and visual representation \(H_v^1\) in a 3D feature space using t-SNE on the SIMS dataset, as shown in Figure 4.

The experiments show that there are modality distribution gaps between audio and visual features, as well as gaps within each modality. However, the hyper-modal representation learned through exchange with audio and visual features, dominated by the text modality, clusters within the same distribution. This indicates that the hyper-modal representation can reduce inter-modal and intra-modal distribution differences between audio and visual representations, exhibiting higher compatibility and reducing the difficulty of subsequent exchange fusion.

Effects of different hyperparameters

The AMTE model incorporates two key hyperparameters: the exchange ratio controller \(\phi\) and the cross-modal fusion depth, denoted as Depth. The hyperparameter \(\phi \in [0, 1]\) determines the threshold for token exchange within both the Hyper-modal Exchange Fusion Module and the Cross-Modal Exchange Fusion Module, effectively controlling the proportion of tokens selected for feature supplementation based on their attention scores relative to the 0th token. Depth specifies the number of layers employed in the Cross-Modal Exchange Fusion Module. To investigate the sensitivity of AMTE to these parameters, we conducted experiments on the MOSEI dataset by varying \(\phi\) and Depth. The results are presented in Figure 5.

The experimental findings indicate that optimal performance is achieved when \(\phi\) is set to 0.2 and Depth is set to 3. A suboptimal value of \(\phi\) (i.e., too low) prevents sufficient supplementation for tokens carrying weak emotional cues, as fewer tokens meet the exchange threshold. Conversely, an excessively high \(\phi\) leads to the replacement of a larger fraction of tokens, potentially overwriting valuable modality-specific features with information from other modalities, which can be detrimental. Regarding Depth, a smaller value limits the extent of interaction and learning between the language modality and the hyper-modal representation within the cross-modal fusion stage. Conversely, increasing the Depth beyond the optimal value introduces computational redundancy without yielding further performance gains, potentially leading to overfitting or performance degradation.

Conclution

Addressing the core challenges of modal distribution differences, inefficient cross-modal interaction, and insufficient contextual modeling in multimodal sentiment analysis, this paper proposes an Adaptive Multimodal Transformer based on Exchanging (AMTE) model. This model utilizes an innovative exchange fusion mechanism to enhance cross-modal local features through dynamic feature compensation, while preserving the specificity of each modality. Firstly, redundant information and noise in each modality’s features are removed through an embedding module. In the adaptive hyper-modal exchange fusion module, AMTE generates a distribution-consistent hyper-modal representation by exchanging and fusing multi-level text features with visual and audio modalities, effectively reducing distribution differences between modalities. In the cross-modal exchange fusion stage, the language modality dominates the integration of emotional information, and the accuracy of sentiment analysis is improved by combining contextual information. Experimental results demonstrate that AMTE performs excellently in sentiment classification tasks on multiple multimodal sentiment datasets such as MOSEI, MOSI, and SIMS, significantly outperforming existing baseline models. This proves the effectiveness of AMTE in improving the efficiency of cross-modal information fusion and enhancing the understanding of emotional expressions.

Data availability

Access to our datasets is openly provided. CMU-MOSI can be downloaded from https://multicomp.cs.cmu.edu/resources/cmu-mosi-dataset/. CMU-MOSEI can be downloaded from http://multicomp.cs.cmu.edu/resources/cmu-mosei-dataset/. CH-SIMS can be downloaded from https://github.com/thuiar/MMSA.

References

Kaur, R. & Kautish, S. Multimodal sentiment analysis: A survey and comparison. Research anthology on implementing sentiment analysis across multiple disciplines 1846–1870 (2022).

Baltrušaitis, T., Ahuja, C. & Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.41, 423–443 (2018).

Das, R. & Singh, T. D. Multimodal sentiment analysis: A survey of methods, trends, and challenges. ACM Comput. Surv.55, 1–38 (2023).

Lai, S., Hu, X., Xu, H., Ren, Z. & Liu, Z. Multimodal sentiment analysis: A survey. Displays 80, 102563 (2023).

Ghorbanali, A. & Sohrabi, M. K. A comprehensive survey on deep learning-based approaches for multimodal sentiment analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev.56, 1479–1512 (2023).

You, Q., Cao, L., Jin, H. & Luo, J. Robust visual-textual sentiment analysis: When attention meets tree-structured recursive neural networks. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 1008–1017 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Learning language-guided adaptive hyper-modality representation for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 756–767 (2023).

Tsai, Y.-H. H. et al. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. In Proceedings of the conference. Association for computational linguistics. Meeting, vol. 2019, 6558 (2019).

Han, W., Chen, H. & Poria, S. Improving multimodal fusion with hierarchical mutual information maximization for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 9180–9192 (2021).

Hazarika, D., Zimmermann, R. & Poria, S. Misa: Modality-invariant and-specific representations for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM international conference on multimedia, 1122–1131 (2020).

Wu, Z., Gong, Z., Koo, J. & Hirschberg, J. Multimodal multi-loss fusion network for sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 3588–3602 (2024).

Zhu, L., Zhu, Z., Zhang, C., Xu, Y. & Kong, X. Multimodal sentiment analysis based on fusion methods: A survey. Inf. Fusion95, 306–325 (2023).

Poria, S., Cambria, E. & Gelbukh, A. Deep convolutional neural network textual features and multiple kernel learning for utterance-level multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2015 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2539–2544 (2015).

Pérez-Rosas, V., Mihalcea, R. & Morency, L.-P. Utterance-level multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 973–982 (2013).

Zadeh, A. et al. Memory fusion network for multi-view sequential learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 32 (2018).

Morvant, E., Habrard, A. & Ayache, S. Majority vote of diverse classifiers for late fusion. In Structural, Syntactic, and Statistical Pattern Recognition: Joint IAPR International Workshop, S+ SSPR 2014, Joensuu, Finland, August 20-22, 2014. Proceedings, 153–162 (Springer, 2014).

Zadeh, A., Chen, M., Poria, S., Cambria, E. & Morency, L.-P. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.07250 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Efficient low-rank multimodal fusion with modality-specific factors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.00064 (2018).

Xiao, L., Wu, X., Wu, W., Yang, J. & He, L. Multi-channel attentive graph convolutional network with sentiment fusion for multimodal sentiment analysis. In ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 4578–4582 (IEEE, 2022).

Lin, Z. et al. Modeling intra-and inter-modal relations: Hierarchical graph contrastive learning for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 29th international conference on computational linguistics, vol. 29, 7124–7135 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022).

Zhao, T. et al. A graph convolution-based heterogeneous fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. Appl. Intell.53, 30455–30468 (2023).

Tang, J., Ni, B., Yang, Y., Ding, Y. & Kong, W. Mecg: Modality-enhanced convolutional graph for unbalanced multimodal representations. J. Supercomput.81, 319 (2025).

Zhou, M. et al. Tcan: Text-oriented cross attention network for multimodal sentiment analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.04545 (2024).

Sun, L., Lian, Z., Liu, B. & Tao, J. Efficient multimodal transformer with dual-level feature restoration for robust multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput.15, 309–325 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 (2019).

Baltrušaitis, T., Robinson, P. & Morency, L.-P. Openface: an open source facial behavior analysis toolkit. In 2016 IEEE winter conference on applications of computer vision (WACV), 1–10 (IEEE, 2016).

McFee, B. et al. librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in python. SciPy 2015, 18–24 (2015).

Eyben, F., Wöllmer, M. & Schuller, B. Opensmile: the munich versatile and fast open-source audio feature extractor. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 1459–1462 (2010).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Zadeh, A., Zellers, R., Pincus, E. & Morency, L.-P. Mosi: multimodal corpus of sentiment intensity and subjectivity analysis in online opinion videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.06259 (2016).

Zadeh, A. B., Liang, P. P., Poria, S., Cambria, E. & Morency, L.-P. Multimodal language analysis in the wild: Cmu-mosei dataset and interpretable dynamic fusion graph. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2236–2246 (2018).

Yu, W. et al. Ch-sims: A chinese multimodal sentiment analysis dataset with fine-grained annotation of modality. In Proceedings of the 58th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics, 3718–3727 (2020).

Williams, J., Kleinegesse, S., Comanescu, R. & Radu, O. Recognizing emotions in video using multimodal dnn feature fusion. In Proceedings of Grand Challenge and Workshop on Human Multimodal Language (Challenge-HML), 11–19 (2018).

Yu, W., Xu, H., Yuan, Z. & Wu, J. Learning modality-specific representations with self-supervised multi-task learning for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 35, 10790–10797 (2021).

Han, W. et al. Bi-bimodal modality fusion for correlation-controlled multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 international conference on multimodal interaction, 6–15 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Cross-modal enhancement network for multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Transactions on Multimed. 25, 4909–4921 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Tetfn: A text enhanced transformer fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. Pattern Recognit.136, 109259 (2023).

Hu, G. et al. Unimse: Towards unified multimodal sentiment analysis and emotion recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.11256 (2022).

Fu, Y., Zhang, Z., Yang, R. & Yao, C. Hybrid cross-modal interaction learning for multimodal sentiment analysis. Neurocomputing 571, 127201 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Multimodal transformer with adaptive modality weighting for multimodal sentiment analysis. Neurocomputing572, 127181 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Guangdong University of Science and Technology (GKY-2024BSQDK-13/14) and the National Language Commission (YB145-122).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.T.: Term, Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing-Review, Supervision and Project administration and Funding acquisition. F.F.: Term, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Visualization and Formal analysis. M.W.:Term, Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing-Review, Supervision and Project administration and Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tuerhong, G., Fu, F. & Wushouer, M. Adaptive multimodal transformer based on exchanging for multimodal sentiment analysis. Sci Rep 15, 27265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11848-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11848-4