Abstract

Self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS) is associated with infrequent seizures but may cause behavioral problems and require more acceptable and effective intervention options. We aimed to compare the efficacy, adherence and safety of different levetiracetam administration methods for SeLECTS. We conducted a prospective, open-label and non-inferiority study; 192 children with SeLECTS were randomized into three groups: Group A (65 patients) received 2/3 of the daily dose in the evening and 1/3 in the morning; Group B (62 patients) took a single night-time dose; and Group C (65 patients) received equal split doses twice daily. After 6- and 12-months of treatment, Groups A and B were non-inferior to Group C in terms of seizure control and electroencephalogram normalization rate. Group B required the lowest effective dose, while Group C had higher blood drug concentrations (P < 0.05). Group B had lower Conners Parent Symptom Questionnaire scores for conduct problems, psychosomatic problems and anxiety compared to Group C (P < 0.05). Groups A and B had higher levels of satisfaction and adherence than Group C (P < 0.05), with no difference in adverse events. Collectively, these results demonstrated that for SeLECTS patients, a night-time single administration of levetiracetam ensures efficacy and improves both medication adherence and satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS), previously known as benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, is the most prevalent idiopathic focal epilepsy syndrome in children. SeLECTS has an estimated prevalence of 10 per 210,000 and constitutes roughly 10–20% of all pediatric epilepsy cases. Disease onset typically occurs around 3–13 years-of-age, and most cases resolve naturally before 16 years-of-age1,2. Seizures exhibit distinctive characteristics, typically occurring shortly after falling asleep or just before awakening in the early morning, with partial seizures representing the predominant form. These are characterized by focal sensorimotor symptoms, including mouth deviation to one side, facial twitching, drooling and gurgling sounds in the throat, which may rapidly generalize into tonic-clonic seizures with impaired consciousness3.

Since SeLECTS is usually associated with a low frequency of seizures and tends to resolve spontaneously, the necessity for antiepileptic treatment in SeLECTS has been the source of much debate historically4. Recent studies, however, have questioned this traditionally benign perception, revealing associations with cognitive deficits, particularly in terms of language and executive functioning, alongside increased risks of behavioral difficulties, social impairments, and psychiatric comorbidities5,6,7,8. The neurobiological basis of cognitive dysfunction in children with SeLECTS has yet to be fully clarified. Epileptic seizures can cause neuronal damage, thus affecting the stability of cell membranes and leading to functional deficits in the nervous system. The increased excitability of neurons can result in sleep disturbances, irreversible cognitive and behavioral impairments, the disruption of cortical functionality, and negatively impact brain development9,10. Therefore, there is a need for clinicians to carefully consider how we might strike a balance between the acceptability and efficacy of treatment.

Levetiracetam (LEV) is one of the most used drugs for the treatment of SeLECTS. This antiepileptic agent works through a novel mechanism involving SV2A binding, which appears to modify the dynamics of presynaptic neurotransmitter release11. Moreover, LEV demonstrates additional pharmacological effects involving the modulation of intracellular calcium signaling, GABAergic neurotransmission, and AMPA receptor-mediated excitatory pathways, and is known for its favorable pharmacokinetic properties, effectiveness, tolerability and safety profile12.

Traditional antiepileptic drug regimens are developed primarily based on the half-life of the drug. The total daily dose is typically divided into 2–3 portions, with the patient taking the medication at evenly spaced intervals to maintain a relatively stable blood concentration within the body13. However, certain types of epilepsy, such as SeLECTS, are associated with the onset of seizure during the night14. For patients with this type of epilepsy, traditional medication regimens may lack specificity. High blood concentrations are favorable against the night seizure flare but may increase the risk of adverse effects during the day15.

Over recent years, with the continuous development and exploration of chronopharmacology, the traditional concepts of equally spaced dosing based on the half-life of a drug are gradually being changed. This theory suggests administering medications during the active phase of the disease to achieve peak drug concentration, followed by dose reduction or discontinuation during the inactive phase. This approach aims to effectively treat the disease while minimizing the risk of adverse drug reactions and improving adherence16,17. LEV and valproic acid could be used to control status epilepticus with intravenous loading infusion, suggesting their safety in a single high-dose administration18. In a randomized controlled trial conducted by Chen Lijuan et al., a night-time large dose of sodium valproate was shown to help control epileptic discharge and improve cognitive function in 45 children with SeLECTS19. However, there are no reports on different LEV administration methods for treating SeLECTS. Therefore, this study aims to objectively investigate the efficacy and safety of different LEV administration methods for the treatment of SeLECTS.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

This was a prospective, parallel, open-label, non-inferiority and randomized controlled trial that included 210 children undergoing primary treatment for SeLECTS at the Department of Pediatric Neurology of West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, from January 2021 to December 2023. This trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry Website (https://www.chictr.org.cn/; first posted: January 8, 2021; Registration number: ChiCTR2100041861). The study protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the Chinese Ethics Committee of Registering Clinical Trials [no. ChiECRCT20210008]. All parents/guardians provided written informed consent before screening. This research was conducted in strict accordance with the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

(1) Diagnosis met the SeLECTS criteria established by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) in 202220.

(2) Given the self-limiting nature of SeLECTS in some children during adolescence, which may affect the assessment of treatment efficacy, this study included patients with an age of onset between four and 13 years-of-age.

(3) More than two seizure episodes per year before enrollment.

(4) Electroencephalogram (EEG) findings were consistent with normal background activity, with repetitive spikes, sharp waves, spike-slow waves, or sharp-slow waves in the central and/or temporal regions, with significant increases during sleep.

(5) The family agreed to take medication regimens and signed an informed consent form.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Presence of brain lesions, vascular malformations, or other neurological disorders.

(2) Coexisting severe cardiac, hepatic, or renal insufficiency.

(3) Poor treatment compliance.

Methods

A total of 210 children were assessed for eligibility, and four were excluded because they declined to participate. All 206 children were treated with LEV (Keppra®, UCB Pharma S.A., Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium). The dosing regimen was as follows: LEV was initiated at 10–20 mg/kg/day, with gradual titration to the minimum dose for seizure control and a maximum dose not to exceed 60 mg/kg/day. Using the online tool Research Randomizer (https://www.randomizer.org/), participants were randomly assigned to the following three groups:

Group A (n = 69): Two-thirds of the daily dose was administered at bedtime, and the remaining one-third in the morning.

Group B (n = 65): The children received a single daily dose before bedtime.

Group C (n = 72): The children were given 1/2 of the total daily dose in the morning and 1/2 before bedtime (Fig. 1).

Follow-up

The children in all three groups were followed up for one year. Follow-up was conducted by telephone calls and return to the hospital for review. Patients returned to the hospital for follow-ups in months 3, 6 and 12; telephone follow-ups were conducted once a month.

Observation indicators

Baseline data

We recorded key clinical data from all patients, including baseline information such as gender, age, age at first seizure onset, and age at the start of treatment. In addition, we documented the timing and frequency of seizures, seizure type, baseline EEG, and the results of several surveys, including Conners Parent Symptom Questionnaire (PSQ)21the Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (DSM-5), Swanson, Nolan and Pelham-IV rating scales (SNAP-IV) and Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS).

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome was the proportions of patients with seizure control after six and 12 months of treatment in three groups.

Secondary outcome

(1) The sleep EEG (> 4 h) normalization rate after six and 12 months of treatment.

(2) Treatment satisfaction: The Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) was used to measure the satisfaction of guardians22. The TSQM covers three dimensions: effectiveness, side effects, convenience and global satisfaction. The questionnaire employs a Likert 5-level scoring system, with 5 points recorded for complete satisfaction and 1 point recorded for dissatisfaction, for a total of 100 points.

(3) Compliance: The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 (MMAS-8) was used to assess the compliance scores of the three groups23. The total score of this scale is 10. The higher the score, the better the adherence.

(4) Mean effective drug dosage and blood trough concentration collected before night-time administration. Blood drug concentrations were collected from a total of 130 pediatric patients.

(5) Non-systematic adverse reactions reported by family members, such as drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness and decreased appetite.

(6) Co-morbidity assessment: Behavioral problems were evaluated before and after treatment using PSQ, SNAP-IV, DSM-5 and YGTSS.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software(SPSS Statistics; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Measurement data are described as mean ± standard deviation (X̅ ± SD) or median (interquartile range). Efficacy evaluation was conducted using non-inferiority testing24. Categorical data are described using frequencies and percentages. The scientific committee defined the non-inferiority margin for the difference in cure rates between groups as 15%. Previous studies showed efficacy estimations with LEV in a range of 64–83%25,26,27. Based on an assumed 75% efficacy rate in the control group, a non-inferiority margin of 15%, and a similar dropout rate in the three groups, we determined that at least 132 participants (44 per group) was needed to determine non-inferiority with a power of 80% at an alpha error of 5% (one-sided test). Satisfaction, compliance, and medication-related adverse reactions were analyzed by difference testing. Group comparisons were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for measurement data that followed a normal distribution. The rank-sum test was used for group comparisons for data that did not follow a normal distribution. Categorical data comparisons between groups were conducted using the chi-squared test. The study protocol did not include any sub-group or sensitivity analyses, as all statistical comparisons were strictly limited to the a priori defined primary and secondary outcomes. There were no missing data in the primary outcome for the three groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of general data

Patients were recruited from January 2021 to December 2023. Follow-up for efficacy and adverse reactions ended in December 2024. During the trial, four patients in Group A, three patients in group B, and seven patients in Group C discontinued their allocated intervention due to adverse effects; these patients changed to another treatment and were lost to follow-up. Consequently, the final analysis included 65 participants in Group A, 62 in Group B, and 65 in Group C (Fig. 1). The three groups were compared in terms of gender, age, age at first seizure onset, age at the start of treatment, seizure type, seizure frequency and duration before treatment, and EEG discharge locations. Differences between groups for these variables were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). For detailed information, refer to Supplementary Table S1.

Efficacy evaluation after six and 12 months of treatment

After six and 12 months of treatment with different medication regimens, there were no statistically significant differences between the three groups in terms of seizure control rates (Table 1). In the non-inferiority test, the seizure control rate in Group A and Group B were non-inferior to those in Group C after six months of treatment. However, after 12 months of treatment, the seizure control rates in Group A could not be considered non-inferior to Group C, while the seizure control rate in Group B was still non-inferior to Group C (Supplementary Table S2).

Comparison of EEG changes after treatment

EEG normalization rates between the three groups after six or 12 months of treatment did not differ significantly (P > 0.05). The EEG normalization rate after six months of treatment was significantly lower than that after 12 months (P < 0.05), thus suggesting that the EEG normalization rate increased as treatment extended (Table 1). The EEG normalization rates in Group A and Group B after both 6 and 12 months of treatment were non-inferior to those in Group C (Supplementary Table S3).

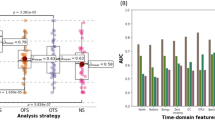

Mean effective drug dose and blood drug concentration

Analysis of the mean effective drug dose indicated that Group B required a significantly lower dose than Groups A and C (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Furthermore, the blood trough concentration of children was monitored as medication dosages were adjusted. An upwards trend in blood concentrations was observed with increasing dosages in all three groups, in which the overall blood drug concentration in Group C was significantly higher than that in Groups A and B (P < 0.05, Fig. 2).

Survey of treatment satisfaction and compliance scores after 12 months

After 12 months of treatment, analysis of the TSQM scale scores for the three groups revealed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in effectiveness, side effects, convenience, and global satisfaction. Statistical comparison of MMAS-8 compliance scores revealed that children in Groups A and B had significantly higher compliance scores than those in group C (P < 0.05). See Table 3.

Comparison of PSQ, DSM-5, SNAP-IV and YGTSS scores

Changes in the PSQ score after 12 months of treatment is shown in Table 4. Group A showed increased impulsive hyperactive problem scores after treatment. Group B showed a reduction in both conduct problem scores and hyperactivity index, while Group C showed a reduction in conduct problems but an increase in psychosomatic scores; these changes were all statistically significant (P < 0.05). Except for the hyperactivity index, no significant differences were observed between the three groups in terms of PSQ scores before treatment (P > 0.05). After 12 months of treatment, Group B showed lower scores in conduct problems, psychosomatic problems, and anxiety when compared to Group C. However, Group C had lower scores for learning problems and impulsive hyperactive problems when compared to Groups A and B; these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

No statistically significant differences were observed in terms of the DSM-5, SNAP-IV, or YGTSS scores between the three groups at either baseline or post-treatment assessments. After treatment, the DSM-5 hyperactivity/impulsivity score, DSM-5 total score, SNAP-IV hyperactivity/impulsivity score, SNAP-IV oppositional defiant score, and YGTSS score were significantly reduced (P < 0.05). The YGTSS impairment scale before and after treatment was mild. The DSM-5/SNAP-IV inattention scores were significantly reduced in Group C after treatment (P < 0.05), while the other two groups were not (see Supplementary Table S4-S6 and Figure S1-S3).

Comparison of adverse events

The reported adverse reactions were drowsiness (n = 12), dizziness (n = 11), headache (n = 8), gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 6) and mood disorders (n = 6). No serious adverse events were reported. The incidence of adverse events in Groups A, B, and C did not differ significantly (P > 0.05). However, the incidence rate in Group B was 11.3%, which was noticeably lower than that of Group A (20.0%) and Group C (26.2%). Refer to Table 5.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that nocturnal single-dose levetiracetam were non-inferior to traditional split-dose administration in terms of seizure control and EEG normalization after six and 12 months of treatment. Notably, Group B achieved comparable efficacy with a significantly lower effective dose (29.3 mg/kg/day vs. 40.4 mg/kg/day in Group C, P < 0.05) and reduced blood drug concentrations, thus suggesting optimized pharmacokinetics. Group B also showed superior behavioral outcomes, with lower PSQ scores in conduct problems, psychosomatic issues, and anxiety, alongside higher treatment satisfaction and adherence. These findings support night-time single dosing as a viable strategy to balance efficacy, safety, and practicality in SeLECTS management.

SeLECTS tends to start during school age, and children at this stage have weak medication-taking autonomy, especially those who are not under parental supervision (e.g., boarding at school). For parents, sporadic seizures tend to cause a relaxation of vigilance, coupled with concerns about the impact of nerve drugs on their children’s daytime performance; medication administration twice or more a day is often difficult to adhere to. Previous studies have compared the different dosing schedules of lithium for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Despite inducing substantial fluctuations in plasma lithium concentrations, once-daily dosing regimens demonstrate comparable therapeutic efficacy to multiple daily doses while potentially offering additional benefits, including reduced nephrotoxicity risk and improved medication adherence28,29. Our research results suggested that all three treatment regimens are effective in controlling seizures and improving abnormal EEG discharges in children with SeLECTS. It is worth noting that in terms of 12-month seizure control rates, Group A lost non-inferiority to Group C, whereas Group B maintained it. While sample size and confounding factors (e.g., dosing adjustments) may have influenced these outcomes, the sustained efficacy of once-daily nocturnal dosing suggests superior long-term tolerability or therapeutic consistency, thus supporting its role as a viable alternative to traditional regimens.

Pelzl et al. compared the efficacy and pharmacokinetics of valproic acid administered as a single daily dose versus divided doses thrice daily. Following a once-daily evening dose, the plasma VPA reached a maximal value around 2 a.m. and presented equal clinical efficacy30. Also, in our study, we showed that the mean effective dose and blood concentration with a single daily dose were significantly lower than divided doses. This suggests that administering a single dose of LEV at night may allow the plasma concentration to peak at midnight, thus ensuring efficacy while reducing the overall effective drug dosage.

The PSQ scores for the three groups showed that administering once daily at bedtime for SeLECTS patients helped to regulate conduct problems and hyperactivity, and improved conduct problems, psychosomatic problems, and anxiety when compared to the traditional delivery mode. All three regimens were equally effective in improving tics. Research evidence suggests a remarkably high comorbidity rate between SeLECTS and ADHD, with prevalence estimates reaching up to 60% in some clinical studies31. The behavioral problems observed in SeLECTS patients are closely related to epileptic discharges during sleep. Previous studies have found that SeLECTS comorbid with ADHD had a statistically longer duration of a single episode, a higher proportion of seizures both after falling asleep and before awakening, and higher spike wave frequency in EEG than a non-ADHD group32. One theory suggests that epileptiform discharges may disrupt normal sleep architecture. These sleep disturbances could potentially trigger allostatic overload, thereby impairing neural plasticity, emotional processing, immune function and endocrine pathways which collectively contribute to the development of neuropsychiatric comorbidities5,33. For SeLECTS patients with sleep disorders or behavioral problems, single night-time dosing could be a better choice than split-dose administration. However, Group A had increased impulsive hyperactive problem scores, and Group C had an increased psychosomatic score after treatment. This may be attributed to adverse drug reactions since a systematic review previously revealed that children using LEV have a higher risk of developing aggression, hostility, and nervousness11. Another possibility is that the pathological mechanisms associated with cognitive impairment are not completely blocked by antiepileptic drugs. Recent evidence suggests that synaptic dysfunction may underlie both ADHD and epilepsy, indicating a possible shared pathogenic mechanism related to abnormal brain development34,35. In our research, traditional administration appears to be better in improving inattention based on DSM-5/SNAP-IV results. This needs to be adopted with caution as there was no significant difference in the inattention scores of the three groups after treatment; a study with a larger sample size is needed to verify this point.

With regards to adverse reactions, the incidence in Group B was lower than in Group A and Group C, though this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). This suggests that single-dose LEV may have a potential advantage in reducing adverse events, but further validation is needed.

This study was a controlled trial with a limited sample size and was performed in a single center. It is important to consider the potential impact of sample bias and potential confounders on outcomes, such as differences in patient adherence due to regional and cultural differences. Future studies should incorporate more comprehensive brain function assessments, such as teacher questionnaires, intelligence tests, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Long-term EEG and regular blood concentration monitoring of hospitalized patients could further confirm the efficacy and safety of once-daily dosing at night. Considering the natural remission characteristics of children with SeLECTS after puberty, long-term follow-up research could be made to observe the prognosis of patients’ cognition and behavior after discontinuation of the medication. With the advancement of modern medicine, individualized therapy is receiving increasing levels of attention from scholars and society. However, larger sample sizes with multicenter randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these findings.

In conclusion, for SeLECTS patients, nighttime single administration improves medication adherence and satisfaction. It ensures efficacy and may better ameliorate conduct, psychosomatic, and anxiety problems in children, which may help adapt the current treatment regimen.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Lacey, A. S. et al. Epidemiology of self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS): A population study using primary care records. Seizure 122, 52–57 (2024).

Ross, E. E., Stoyell, S. M., Kramer, M. A., Berg, A. T. & Chu, C. J. The natural history of seizures and neuropsychiatric symptoms in childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (CECTS). Epilepsy Behav. 103(Pt A), 106437 (2020).

Galicchio, S. et al. Self-limited epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes: A study of 46 patients with unusual clinical manifestations. Epilepsy Res. 169, 106507 (2021).

Henzi, B. C. & Datta, A. N. Self-limited focal epilepsies from the parietal and occipital lobes in childhood. Z. Epileptol. 34 (1), 67–77 (2021).

Ragab, O. A., Deeb, F. A. E., Belal, A. A. & Al-Malt, A. M. Sleep, cognitive functions, behavioral, and emotional disturbance in self-limited focal childhood epilepsies. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiat Neurosurg. 60 (1), 1–13 (2024).

Kim, S. E., Lee, J. H., Chung, H. K., Lim, S. M. & Lee, H. W. Alterations in white matter microstructures and cognitive dysfunctions in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Eur. J. Neurol. 21 (5), 708–717 (2014).

Yin, Y. et al. Abnormalities of hemispheric specialization in drug-naïve and drug-receiving self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsy Behav. 136, 108940 (2022).

Garcia-Ramos, C. et al. Cognition and brain development in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsia 56 (10), 1615–1622 (2015).

Wickens, S., Bowden, S. C. & D’Souza, W. Cognitive functioning in children with self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia 58 (10), 1673–1685 (2017).

Yue, X. et al. The efficacy and cognitive impact of perampanel monotherapy in patients with Self-Limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A retrospective analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 19, 1263–1271 (2023).

Halma, E. et al. Behavioral side-effects of Levetiracetam in children with epilepsy: a systematic review. Seizure 23 (9), 685–691 (2014).

Contreras-García, I. J. et al. Levetiracetam mechanisms of action: from molecules to systems. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 15 (4), 475 (2022).

Gidal, B. E., Ferry, J., Reyderman, L. & Piña-Garza, J. E. Use of extended-release and immediate-release anti-seizure medications with a long half-life to improve adherence in epilepsy: A guide for clinicians. Epilepsy Behav. 120, 107993 (2021).

Borggraefe, I. & Neubauer, B. A. Self-limited focal epilepsies of childhood syndromes (SeLFEs)-an overview. Clin. Epileptol. 37, 3–8 (2024).

Nersesjan, M. et al. Evaluation of antiseizure medication concentration ranges in blood samples using an automated big data approach. Epilepsia.66(6),1888-1898(2025).

Lemmer, B. Chronobiology, drug-delivery, and chronotherapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 59 (9–10), 825–827 (2007).

Sousa, E., Pinto, M., Ferreira, M. & Monteiro, C. Neurocognitive and psychological comorbidities in patients with self-limited centrotemporal Spike epilepsy. A case-control study. Rev. Neurol. 76 (5), 153–158 (2023).

Glauser, T. et al. Evidence-Based guideline: treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children and adults: report of the guideline committee of the American epilepsy society. Epilepsy Curr. 16 (1), 48–61 (2016).

Chen, L. J. & Zhang, Q. S. Treatment of night large dose of sodium valproate on benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A report of 45 cases (in Chinese). Her Med. 35 (9), 951–954 (2016).

Specchio, N. et al. International league against epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood: position paper by the ILAE task force on nosology and definitions. Epilepsia 63 (6), 1398–1442 (2022).

Al-Awad, A. M. & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. The application of the Conners’ Rating Scales to a Sudanese sample: an analysis of parents’ and teachers’ ratings of childhood behaviour problems. Psychol Psychother 75(Pt 2), 177-187 (2002).

Atkinson, M. J. et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a National panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual. Life Out. 2, 12 (2004).

Morisky, D. E., Ang, A., Krousel-Wood, M. & Ward, H. J. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J. Clin. Hypertens. 10 (5), 348–354 (2008).

Silva, G. T. D., Logan, B. R. & Klein, J. P. Methods for equivalence and noninferiority testing. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 15 (1), 120–127 (2009).

Li, J., Xiao, N. & Chen, S. Efficacy and tolerability of Levetiracetam in children with epilepsy. Brain Dev. 33 (2), 145–151 (2011).

Zhao, T. et al. Long-term safety, efficacy, and tolerability of Levetiracetam in pediatric patients with epilepsy in uygur, china: A retrospective analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 120, 108010 (2021).

Tekgül, H., Gencpinar, P., Çavuşoğlu, D. & Dündar, N. O. The efficacy, tolerability, and safety of Levetiracetam therapy in a pediatric population. Seizure 36, 16–21 (2016).

Malhi, G. S. & Tanious, M. Optimal frequency of lithium administration in the treatment of bipolar disorder: clinical and dosing considerations. CNS Drugs. 25 (4), 289–298 (2011).

Carter, L., Zolezzi, M. & Lewczyk, A. An updated review of the optimal lithium dosage regimen for renal protection. Can. J. Psychiatry. 58 (10), 595–600 (2013).

Pelzl, G. & Mamoli, B. Einmaltagesdosis Mit valproinsäure. Eine Pharmakodynamische und klinische studie [A single daily dose with valproic acid. A pharmacodynamic and clinical study]. Wien Klin. Wochenschr. 104 (10), 286–289 (1992).

Aricò, M., Arigliani, E., Giannotti, F. & Romani, M. ADHD and ADHD-related neural networks in benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 112, 107448 (2020).

Wang, M. Y. et al. A clinical study on children with self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder comorbidity (in Chinese). Chin. J. Neuromed. 23 (6), 552–559 (2024).

Peter-Derex, L. et al. Sleep disruption in epilepsy: ictal and interictal epileptic activity matter. Ann. Neurol. 88 (5), 907–920 (2020).

Lepeta, K. et al. Synaptopathies: synaptic dysfunction in neurological disorders - a review from students to students. J. Neurochem. 138 (6), 785–805 (2016).

He, Z. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors. Epilepsia Open. 9 (4), 1148–1165 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients and caregivers who collaborated in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82071686) and a Grant from the clinical research fund of West China Second University Hospital(No. KL115 and KL072).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.F., Y.S., J.Z. and X.W. contributed to the acquisition of data by enrolling patients and to the interpretation of the data. Y.L., X.R., H.L., J.C., J.W, X.G., and X.T. responsible for analyzing and verifying the data reported in the manuscript. J.Z., J.G., and R.L. contributed to the concept or study design. All authors had full access to study data, reviewed, edited, and provided final approval of the manuscript content, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. *Lijuan Fan and Yajun Shen contribute equally to this work.

Ethical approval

The study protocol, amendments and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the Chinese Ethics Committee of Registering Clinical Trials [no. ChiECRCT20210008]. All parents/guardians provided written informed consent before screening. The study conforms with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Supplementary Information

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, L., Shen, Y., Zhang, J. et al. Safety and efficacy of one-dose nocturnal levetiracetam for the treatment of self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 15, 34302 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11906-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11906-x