Abstract

Little exploration of the impact of environmental penalties on climate-friendly technology innovation (CFTI). This paper explores the impact of environmental penalties, set within an institutional context, on the promotion of climate-friendly technological innovation. Employing a qualitative analysis grounded in signaling theory and challenge/threat theory, this study utilizes data from various Chinese cities and applies city- and year-specific two-way fixed effects models to assess the effects of environmental penalties on climate-friendly technological innovations. The findings reveal that environmental penalties have an inverted ‘U-shaped’ nonlinear effect on such innovations. There is a critical inflection point where environmental penalties shift from promoting to inhibiting these innovations. Additionally, the study finds that environmental penalties also impact the development levels of the digital economy and financial technology, both of which support climate-friendly technological innovation. Therefore, it can be inferred that environmental penalties indirectly influence climate-friendly technological innovation through their effects on the digital economy and financial technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The imposition of administrative penalties for violations of the legal regime for environmental protection (i.e., EPP) is an important policy tool for addressing climate change. The existing literature on EPP has reached two opposed conclusions. One conclusion suggests that EPP creates peer and short-term governance effects, reducing violations by penalized firms and encouraging the adoption of green technology innovations among their peers1,2 Another conclusion is that EPP cause penalized firms to pass on the costs of penalties to consumers with no effect on themselves3 and even deteriorate firms’ environmental performance4. China’s EPP in the early years were too lenient to be effective as penalties5. However, in recent years, Chinese city governments have significantly increased EPP. Our statistics indicate that in 2008, a total of 1,649 EPP were imposed by cities nationwide, rising to 644,096 in 2022. This represents a rapid increase of 389.60 times over 14 years. CFTI is a crucial measure to combat climate change6 and is considered a key aspect of corporate environmental performance. How exactly do rapidly increasing EPP affect CFTI? There is no consistent conclusion in the existing literature on this question. Therefore, this paper is based on signal transmission theory and challenge/threat theory.

The level of CFTI is the dependent variable in this paper. Climate-friendly technologies are those that mitigate or adapt to climate change7,8,9. The Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC), jointly published by the European Patent Office and the US Patent Office in 2013, with the Y02 classification is defined as technologies for mitigating or adapting to climate change. To this end, we collected data on patent applications and granted patents under the Y02 classification in each city from 2008 to 2020, obtained from Wisdom Buds, which sources its data from the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO). We then followed the methodologies of Lu et al.10, and Li & Yang11, calculating the ratio of climate-friendly patent applications to the number of enterprises, and the ratio of granted patents to enterprises, to derive the CFTI and rCFTI, which are used as proxy variables for the level of CFTI in cities. Environmental protection penalty is an independent variable in this paper. In China, according to the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the responsible department for enforcing EPP is the environmental protection department at the county level and above. For this reason, we take the city where the penalized enterprises are located as the main line and collect the number of penalties imposed by the environmental protection department on enterprises in each city in each year from Shanghai Da Zhi Cai Hui Data Technology Co., Ltd, whose data comes from administrative organs, to obtain Envadmin, and then divide Envadmin by the number of enterprises in the city EPAP, as a proxy variable for the strength of EPP in the city, and at the same time, standardize Envadmin by the extreme value standardization method to get rEPAP, as another proxy variable for the strength of EPP in the city.

Based on the independent and dependent variables being constructed, we investigate the direct impact of EPP on CFTI with a city and year two-way fixed effects model. Then, drawing on Chen et al.12, and Chen (2023)13, we test the indirect effect of EPP on CFTI using the level of digital economy development and the level of fintech development as the mediating variables. We find that, first, EPP has an inverted “U”-shaped nonlinear effect on CFTI; there is an inflection point in the strength of EPP, and on both sides of the inflection point, EPP promotes and inhibits CFTI, respectively. The reason is that the signalling theory, which originated with Spence (1973)14, suggests that people’s behaviour sends signals to the outside, and that these signals bring about impacts on the recipients. According to the signalling theory, city governments send signals to the market for increased regulation through EPP, which puts regulatory pressure on enterprises. The challenge/threat theory, which originated from Lazaru (1991)15, suggests that when people are faced with less pressure, they perceive it as a challenge and vice versa as a threat. Challenges improve performance, while threats reduce performance. According to the theory, when regulatory pressure is moderate, enterprises see it as a challenge and improve their CFTI; however, when the pressure becomes too great, it is perceived as a threat, which is detrimental to CFTI. Second, the mechanism study shows that EPP also has an inverted “U” non-linear effect on the level of digital economy development and the level of fintech development, both of which are conducive to CFTI. In other words, EPP also indirectly affects CFTI through the level of digital economy and financial technology development.

First, our study can provide a relatively innovative method for measuring environmental regulation in subsequent research. Environmental penalties belong to environmental regulation. Some scholars have used compliance expenditures16, regulatory expenditures17, and pollution costs18 to measure environmental regulation intensity. Some scholars have also used keywords such as ‘ecology’ and ‘environmental protection’, collecting their frequencies from the Government Work Reports of Chinese cities as proxy variables for environmental regulatory intensity19. The former method only reflects a certain aspect of the city government’s implementation of the governance environment, and it is difficult to measure the whole picture of the city government’s environmental governance policy20. The latter method more closely reflects the city government’s attitude and preference towards environmental protection, yet it does not fully capture the effectiveness of the city’s implementation of environmental regulation. According to the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the environmental protection departments at the county level and above are authorized to impose EPP for violations of the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China within their jurisdiction. This implies that the administrative penalties imposed by the environmental protection departments better reflect the strength of EPP. Therefore, our study adopts a more reasonable and novel approach to measuring environmental regulation.

Second, our study contributes to some of the literature on CFTI. Concerning CFTI, recent studies have centered around people’s climate-friendly behaviors9, financial support6,8, social spillovers from learning and imitation21, social norms7 and international cooperation22,23, among others. For instance, a major challenge in implementing CFTI is securing financing for these projects, yet the venture capital financing available for CFTI has been declining6. In developing countries, the financial sector tends to be particularly hesitant about CFTI projects8. Through learning and imitation, social spillovers can drive climate-friendly technology innovations and applications such as solar panels and hybrid cars (Carattini et al., 2020)21. In addition, cultural diversity can also promote green technology innovation, which may benefit CFTI24. However, little literature has explored the impact of EPP on CFTI. Our study provides new evidence to promote CFTI and enriches the literature related to CFTI. CFTI is a green technology innovation, and our research has refined green finance innovation into CFTI.

Finally, our study contributes to the emerging literature related to EPP. Scholars have studied the economic consequences of EPP, focusing on firms’ financial and environmental effectiveness. In terms of financial effectiveness, EPP increase the cost of debt financing and the cost of equity financing for firms25, and reduce firms’ cash flow25. In terms of environmental effectiveness, EPP has a peer effect, which promotes the quantity and quality of green technology innovation of the penalized firm’s peer firms2 and EPP only has a short-term effect, which reduces the violations of the penalized firms in the short term1. However, China’s EPP are too lenient and the amount of penalties is low5,26, which makes it difficult to achieve the effect of pollution control26. Increased penalties may deteriorate firms’ environmental performance4. In addition, firms may pass on the cost of penalties to consumers, with no impact on themselves3. Overall, there is no consensus in the existing literature on the effectiveness of environmental protection. Our study enriches the literature on EPP by synthesizing, to some extent, the findings of existing studies on environmental effectiveness.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: sect. “Testable hypotheses” clarifies our testable hypothesis. Section “Models, variables and data” describes our research methodology. Section “Results” discusses our main empirical results with robustness tests. Section “Conclusion, implications, and outlook” conducts transmission mechanism tests. Section 6 provides a discussion. Finally, the paper provides a summary.

Testable hypotheses

Institutional context

Administrative penalties serve as an important means for Chinese governments at all levels to enforce administrative management and are a key tool in ensuring the implementation of the legal system. The Chinese legislature enacted the Administrative penalty Law of the People’s Republic of China in 1996, subsequently amending it in 2009, 2017, and 2021. The Law defines administrative penalties as acts by administrative organs that, during administrative management, punish citizens, legal persons, or other organizations for violating administrative orders by limiting their rights or increasing their obligations, as per the law.” Authorities imposing administrative penalties encompass administrative organs, organizations authorized by laws to manage public affairs, and organizations delegated by administrative organs to exercise specific administrative penalty powers. In 1989, China’s legislature enacted the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Environmental Protection, which was amended in 2014. The Law provides that the competent environmental protection authorities of the people’s governments at or above the county level are authorized to impose administrative penalties for violations of the PRC Environmental Protection Law. The competent environmental protection authorities here are the ecological and environmental departments at all levels of government. The Law of the People’s Republic of China on Administrative Penalties provides that “[a] dministrative penalties shall be under the jurisdiction of the administrative organ in the place where the violation occurred.” Accordingly, in practice, the vast majority of violations of the PRC Environmental Protection Law are subject to EPP imposed by ecological and environmental departments at the county and prefectural levels. China is a vast country with unbalanced development, and cities have different cultural concepts, social inclusiveness, and philosophies about penalizing violations. This results in the strength of administrative penalties varying across cities. This provides a good research scenario for examining the issue of CFTI from the perspective of EPP.

Hypotheses

Chen&Zhang (2025)27 proposed a hypothesis at the urban level after analyzing individual behavior at the micro level. In this section, we draw on their approach and use the challenge/threat theory for theoretical analysis.

Direct impact of EPP on CFTI

Enterprises are the principal agents of CFTI6, and government behavior profoundly affects CFTI6,21. As an important government behavior, EPP, through the “information disclosure” system, can send signals to the market and exert regulatory pressure on firms28. This external pressure may be perceived as a challenge by individuals or a threat by firms. For this reason, we analyze the direct impact of administrative penalties on CFTI based on signaling theory and challenge/threat theory.

First, EPP will send a strong signal to enterprises and exert regulatory pressure on their managers. Firstly, there exists an information asymmetry between the government and enterprises regarding the enforcement strength of the environmental protection legal system. Signaling theory suggests that information asymmetry occurs when “different people know different things” and when the parties to a decision do not have the same quantity and quality of information29. Information asymmetry is widespread but can be mitigated through the transmission of various “signals”30. Signaling involves signal senders, signal receivers, and signals31,32. China has developed a comprehensive legal system for environmental protection, but “no law is enough”. Although the Chinese legislature enacted the Administrative Penalty Law of the People’s Republic of China in 1996, a total of 1,649 EPP were imposed by cities across the country in 2008, and this figure rises to 644,096 by 2022. This shows that the real implementation of the legal system of environmental protection is not a quick fix. It also shows that there is a serious information asymmetry between the government and businesses in terms of the extent to which the environmental legal system is actually enforced as it should be. Second, EPP is a high-value signaling behavior with wide dissemination. The implementation of EPP by the government can be regarded as a kind of signaling behavior, in which the government is the signal sender and the enterprise is the signal receiver, and the signal transmitted is the degree to which the environmental protection legal system is strictly enforced. Signaling theory suggests that the stronger the signal, the more attention it will garner from the target audience33. Compared to press releases, holding conferences, and releasing policies, the government imposes EPP on non-compliant companies with stronger signals, which are more likely to attract the attention of the market. According to signaling theory, the more costly the signal is to send and the harder it is to fake, the greater its value to the receiver tends to be32,34.The imposition of EPP by the government on non-compliant companies requires repeated on-site investigations. It strives to achieve conclusive evidence, and also requires confirmation of the fact of violation and public announcement of administrative penalties, etc.; when the violating firms do not accept the penalties, they will also file an administrative reconsideration with a higher level of government. Therefore, compared to other forms, EPP sends high-cost signals that cannot be forged, offering the greatest value to the market. In short, according to the signal theory, the government implements EPP, which is a widespread, high value signaling behavior. Third, the signal transmitted by EPP will create regulatory pressure on business managers. From 2008 to 2022, the strength of EPP imposed by Chinese city governments is gradually increasing. Administrative penalties have a deterrent effect2, which will deter penalized firms and their peer firms and create regulatory pressure. According to the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, all enterprises are required to undertake environmental protection obligations. This means that EPP will have a deterrent effect on all enterprises and bring regulatory pressure. The stronger the EPP, the more frequent the penalties, and the more often they are imposed, the greater the regulatory pressure felt by the enterprises. Business decisions are made by business managers as individuals. Environmental penalties send out the signal formed by the regulatory pressure is bound to have an impact on business managers.

Second, business managers may view regulatory pressure from EPP as a challenge or threat. Individual decision-making depends on both internal and external factors. Stress is an important external factor that affects individual decision-making35, influencing individuals’ decisions at work36, study37,38, and sport39 and many other aspects of performance. In terms of the relationship between stress and performance, scholars have developed the challenge-threat theory based on the cognitive appraisal theories established by Lazarus & Alfert40, Lazarus et al. (1965)41, and other pioneers37,41,42.

Challenge/threat theory suggests that in the face of stress, individuals engage in situational demand assessment and assessment of their own resources18,37,39,42,43,44. Situational requirements assessment is a Primary appraisal, which corresponds to the resources required for stress in terms of the three dimensions of required effort, uncertainty, and danger; and the own resources assessment is a Secondary appraisal (Secondary appraisal), which is used by individuals to assess the resources for coping with stress45,46. Based on the assessment results, individuals appraise stress as a challenge and vice versa as a threat when they believe that their own resources meet or exceed the demands of the situation39,43,47. For example, when athletes assess that their resources meet or exceed greater than the situational demands, they enter the challenge state, and vice versa, the threat state39. Students enter the challenge state when they assess that their resources can meet the demands of the learning task37,38. Subsequent studies have also concluded that individuals appraise stress as a challenge and vice versa as a threat when the resources they possess meet, exceed, or fall slightly short of what is required48.

According to challenge/threat theory, regarding regulatory pressure from EPP on business managers, business managers will also conduct an assessment of situational requirements and an assessment of their own resources. When EPP are low, the effort required to cope with regulatory pressure is low, and the accompanying uncertainties and dangers are low. As a result, business managers perceive their resources as being more than, or at most slightly less than, what is required, and thus appraise this lesser regulatory pressure as a “challenge”. Conversely, when EPP are higher, the effort required to cope with higher regulatory pressures is greater, and so are the uncertainties and dangers. Firm managers perceive that the resources they hold are significantly lower than the resources they need, and thus appraise this higher regulatory pressure as a “threat”. In short, when regulatory pressure is low, business managers will appraise it as a “challenge” and vice versa.

Finally, regulatory pressure can lead to an inverted “U”-shaped non-linear relationship between EPP and CFTI. Challenge/threat theory suggests that challenges and threat assessments influence an individual’s subsequent behavior49and are important predictors of future performance50. Challenge leads to a large increase in the amount of blood circulating per minute, a shortening of the time between successive heartbeats, an increase in positive affect, a well-adjusted tendency to lead to high performance, better performance on cognitive and behavioral tasks49, and a tendency for challenge appraisers to use positive coping styles in stressful situations44. Numerous studies have concluded that challenge facilitates good performance43,47. In contrast, threats result in no significant change in the amount of blood circulating per minute and the time between consecutive heartbeats (Wormwood et al., 2019)47, and threat assessors respond negatively44, a maladaptive tendency that contributes to mediocre performance. Thus, threats are not conducive to improved performance43,47. For example, subjects who received a challenge instruction performed better in a bean bag tossing task43, higher ratings of challenge produce favorable physiological and psychological responses thereby favoring dancers’ performances, and challenge leads to better competition performance in athletes compared to ratings as a threat43,50; challenging evaluators are more likely to improve their job performance51; and challenges lead to better student achievement compared to threats37,38,52.

Climate-friendly technology is the most important measure to realize the carbon reduction task, and enterprises are the main body of CFTI6. Since 2008, enterprises in China have started to implement CFTI. In this process, the regulatory pressure generated by EPP affects the CFTI of enterprises. As mentioned above, when EPP are small, business managers will appraise them as “challenges”, which is favorable to the implementation of CFTI. On the other hand, when EPP are too strong, enterprise managers will appraise them as “threatening”, which is not conducive to the implementation of CFTI. Consequently, an inverted U-shaped non-linear relationship exists between EPP and CFTI. For this reason, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1: There is an “inverted U” relationship between EPP and the level of CFTI.

Analysis of digital economy based role channels

Since 2008, the deep integration of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data with the economy has pushed the digital economy to a new level. Enterprises across various industries implement digital innovations, leveraging technologies like artificial intelligence and big data, to advance the digital economy12. Environmental penalties acting on the development of the digital economy can influence CFTI as follows.

There is an inverted “U”-shaped non-linear relationship between EPP and the level of development of the digital economy. Using digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data, enterprises can promote digital innovation based on reconfiguring and integrating digital resources and capabilities to create new products, services, processes, procedures, and business models53,54,55. In addition to CFTI, corporate digital innovation can reduce energy consumption and is also an important means to achieve carbon reduction tasks56,57. Since 2008, Chinese firms have begun to implement digital innovations in droves, thereby driving the development of China’s digital economy at a macro level12. At the same time, China’s environmental protection authorities have rapidly strengthened environmental protection enforcement and implemented increasingly severe EPP. In the process, the regulatory pressure generated by EPP may likewise affect corporate digital innovation. Implementing digital innovation in enterprises requires managers to make a series of decisions. As discussed earlier, when EPP are low, business managers who implement digital innovation appreciate them as a ‘challenge’, which is conducive to the implementation of digital innovations to reduce carbon emissions. On the other hand, when EPP are too strong, business managers who implement digital innovation will appreciate them as a ‘threat’, which is not conducive to the implementation of digital innovation, and thus not conducive to the reduction of carbon emissions. Consequently, an inverted “U-shaped” non-linear relationship exists between EPP and digital innovation. At the macro level, this is reflected in the inverted “U” non-linear relationship between the strength of EPP and the level of development of the digital economy. When EPP are low, they can promote the development of the digital economy; when they are too high, they are detrimental to the development of the digital economy.

The development of the digital economy can contribute to CFTI. This is because, first, reducing business risks promotes CFTI. In the digital economy, firms continue to implement digital innovations. Enterprise digitization significantly reduces the costs of information collection and communication58, and enterprises can collect a large amount of information about key businesses and links at low cost, and then carry out effective management changes, accelerate business model innovation, improve the scientific and rational nature of long-term and short-term decision-making, and reduce business risks55. CFTI, this kind of innovation activity, is considered high-risk behavior59. The reduction of operational risk is conducive to the implementation of such high-risk behaviors as climate-friendly innovation. Second, improving the operational efficiency of enterprises promotes CFTI. In the process of digital economy development, enterprises continuously implement digital innovation. The latter can reduce marginal costs, increase positive economies of scale58, and accelerate the speed of information transfer within the enterprise, according to which the enterprise can carry out more accurate strategic target decomposition, investment, and financing decisions, and market segmentation strategies, thus enhancing the enterprise’s operational efficiency60. Enhanced operational efficiency can improve business performance and financially support the implementation of CFTI. Third, accelerating knowledge accumulation promotes CFTI. Data is the core element of the digital economy, which not only helps to produce new products and services but also can be used for knowledge creation61, helping enterprises accumulate the knowledge needed for CFTI. At the same time, the digital economy facilitates the dissemination of information and knowledge, reduces the flow cost of information technology, and alleviates the problem of information asymmetry12,62, which makes it more convenient for technological cooperation, learning and training, and exchange of talents between regions, and accelerates the flow of knowledge62, which can help enterprises accelerate the accumulation of knowledge required for CFTI. This knowledge accumulation is crucial for CFTI, thereby fostering its development.

In summary, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Environmental penalties indirectly affect CFTI based on an inverted “U” nonlinear impact on the digital economy.

Analysis of fintech based role channels

Since 2008, the integration of digital technologies, including artificial intelligence and big data, with finance has led to the emergence of fintech12. Financial enterprises carry out fintech innovation based on digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data to promote fintech development. Environmental penalties acting on FinTech development can affect CFTI as follows.

There is an inverted “U”-shaped non-linear relationship between EPP and the level of fintech development. Fintech is a financial innovation driven by digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data63. Fintech facilitates the digital transformation of financial institutions, which is conducive to the transfer of offline economic activities to online64 and promotes the consumption of renewable energy resources65, which reduces carbon emissions, and is an important means of realizing the mandate of carbon reduction64,66. Since 2008, Chinese financial firms have begun to implement fintech innovations in droves, thus promoting fintech development in China at the macro level. The fintech innovation of financial enterprises requires a series of decisions made by their managers regarding such innovation. China’s environmental protection authorities have rapidly strengthened environmental protection enforcement and implemented increasingly severe EPP. EPP brings pressure to managers of financial enterprises implementing fintech innovation: firstly, from carbon reduction mandates, and secondly, from secondary pressure on brick-and-mortar firms arising from EPP that adversely affect the repayment ability of the financial firms’ loan customers. As mentioned above, when the EPP are small, the managers of financial firms will appraise them as “challenges”, which will facilitate the implementation of fintech innovations to reduce carbon emissions. On the other hand, when EPP are too strong, financial managers will appraise them as a “threat”, which is not conducive to the implementation of fintech innovations. Consequently, an inverted “U-shaped” non-linear relationship exists between EPP and fintech innovation. At the macro level, this is reflected in the inverted “U” non-linear relationship between the strength of EPP and the level of fintech development. When EPP are low, they can promote fintech development; when they are too high, they are detrimental to fintech development.

Fintech development can promote CFTI. The reasons for this are: first, easing financing constraints promotes CFTI. In China’s bank-led financial system, the primary financing channels for enterprises heavily depend on banks. Therefore, Chinese real enterprises generally face financing constraints. The information asymmetry between banks and real enterprises is the main reason why Chinese enterprises face financing constraints. Based on digital technologies such as big data, fintech can alleviate information asymmetry67, which in turn expands the boundaries of financial services68 and improves the accessibility of financial services69, thus alleviating the financing constraints of real enterprises. In addition, fintech intensifies competition among banks and increases their risk-taking level12, which prompts banks to increase credit investment in real enterprises, thus alleviating the financing constraints of real enterprises. A major challenge in CFTI is securing project financing6. By alleviating the financing constraints of brick-and-mortar enterprises, FinTech can provide funding for climate-friendly innovation projects, thus promoting their development. Second, enhancing the operational efficiency of enterprises promotes CFTI. Based on digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data, financial enterprises have digitized, data-enabled and online financial operations, thus reducing transaction costs such as the cost of information acquisition between financial enterprises and real enterprises68, and improving the speed of transactions between real enterprises and financial enterprises and the efficiency of operations70, which in turn improves the operational efficiency of real enterprises, improves the operational performance of real enterprises and provides financial support for enterprises to implement CFTI. In addition, financial technology can encourage energy consumption from fossil fuels to shift towards clean energy, which may also prompt companies to implement CFTI to utilize clean energy71.

In summary, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Environmental penalties indirectly influence CFTI through their inverted ‘U’-shaped nonlinear impact on fintech.

The relationship between the three hypotheses is shown in Fig. 1.

Models, variables and data

Models

Modeling of direct impacts

China is a geographically vast and unevenly developed country, as noted by Chen et al. (2022, 2023). Each city in China has unique characteristics that impact its CFTI, and these characteristics remain stable over time. To account for this variable, we include city-fixed effects in our study. In addition, China follows a government-led economic structure, wherein the central government annually executes initiatives to promote various technical advancements, including CFTI, throughout all cities. These policies have a pervasive effect on every city and undergo annual modifications. To account for this factor, our study is informed by relevant scholarly works on China, including publications by Chen et al. in 2022 and 2023. Based on this, we establish bidirectional fixed effects for both year and city.

where i and t are city and year subscripts, respectively; \({\alpha }_{i}\) is to capture city fixed effects;\({\lambda }_{t}\) is capturing year-fixed effects, and \(\varepsilon_{i,t}\) is the random error term.\({CFTI}_{it}\) is the dependent variable, i.e., the level of CFTI in year t for city i.\({EPAP}_{it}\) is the independent variable, i.e., the level of EPP in year t for city i.\({EPAP2}_{it}\) is its squared term.\({\beta }_{2}\) is the coefficient of the squared term, if it is significantly negative, the relationship between the EPP and the level of CFTI is “inverted U”. x is a control variable.

Modeling of channels of action

The analysis in Sect. “Hypotheses” shows that EPP indirectly affects CFTI by influencing the development of the digital economy and FTCH. The level of digital economy development (DECO) and financial technology (FTCH) are the mediating variables required to conduct the mechanism test in this section.

To this end, we design the following model by referring to the existing literature that studies the transmission mechanism through multivariate regression (e.g., Chen et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023)2.

\({\text{M}}_{\text{it}}\), the mediating variable, represents the level of digital economy development (DECO) or financial technology (FTCH) in the ith city during the tth year. In Eq. (3), X represents the control variable, identical to that in Eq. (1). Similarly, X is also the control variable in Eq. (2). Drawing from existing literature, such as Chen et al. (2022), we control for factors including economic development, foreign investment, industrial structure, financial development, fiscal decentralization, government technology investment, human capital (and its quadratic term), household consumption, urbanization rate, population size, and population density. Household consumption is calculated as the total retail sales of consumer goods in the city divided by the city’s GDP.

The test procedure is as follows: First, estimate Eq. (2) to determine the impact of EPP on the mediating variables. Second, after incorporating the mediating variable, estimate Eq. (3). If the coefficient of EPP in Eq. (2) and the coefficient of the mediating variable in Eq. (3) are both significant, it indicates the presence of a mediating effect. If the coefficient of EPP in Eq. (3) remains significant, this suggests a partial mediating effect; if not, it implies a complete mediating effect. Fourth, if only one of the coefficients in Eqs. (2) and (3) is significant, the mediating effect should be further examined using the Sobel test.

Variables

Referring to the existing literature, this study was designed with the following independent, dependent, mediating, and control variables (see Appendix A.1 for detailed references).

Dependent variables

The dependent variable in this paper is the level of CFTI (CFTI). Lu et al. (2021), and Li & Yang (2018) measure the level of innovation at the regional level in terms of the number of patent applications and the number of granted patents per capita. Enterprises are the main body of CFTI6. Therefore, we average the number of patent applications and the number of granted patents for climate-friendly technologies by the number of enterprises in the city. To this end, we obtain CFTI by the number of patent applications for climate-friendly technologies/number of enterprises in the city as a proxy variable for the level of CFTI, and we obtain rCFTI by the number of patents granted for climate-friendly technologies/number of enterprises in the city as another proxy variable for the level of CFTI.

Independent variables

The independent variable in this paper is the EPP strength (EPAP). Based on the rationale in Sect. “Introduction”, we obtain EPAP by Envadmin/number of firms in the city as a proxy variable for the strength of EPP. Here, ‘Envadmin’ represents the frequency of penalties imposed on firms within the city by the environmental protection department. In addition, rEPAP is obtained after normalizing Envadmin based on the extreme value normalization method as another proxy variable for the strength of EPP.

Control variables

Referring to the existing literature12, this paper controls for various factors including the level of economic development, industrial structure, foreign direct investment, carbon emission intensity, financial development, financial efficiency, fiscal decentralization, human capital, urbanization rate, population density, and population size.

Mediating variables

Digital Economy (DECO) is measured by constructing a digital economy index using factor analysis. See Appendix A.2 for variable settings.

Financial Technology (FTCH). Following Li et al. (2020)72, we construct keywords for search and calculation to determine the level of FinTech development in each city, and the variable setting is shown in Appendix A.3.

Data

Data sources

Carbon reduction regulation in China, which dates back to 2008, is reflected in the China Urban Statistical Yearbook, updated through 2020. For this reason, this paper empirically analyzes the data of Chinese cities from 2008 to 2020. In this paper, the data are processed as follows: (1) missing samples are eliminated; (2) the China Urban Statistical Yearbook no longer reports FDI in cities in 2020, so FDI in 2020 is linearly interpolated; (3) taking the natural logarithm eliminates the effect of outliers. To mitigate the effect of outliers, this paper applies the upper and lower 1% Winsorize shrinkage treatment to continuous variables, except those transformed by the natural logarithm. Finally, we obtained 3,293 annual-city observations.

The number of patent applications and the number of granted patents for climate-friendly technologies are from Wisdom Sprout, whose data comes from the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) but is easier to access. Data on EPP and the number of enterprises are obtained from Shanghai Da Zhi Cai Hui CFTI Technology Co., Ltd, with the CFTI data originating from the State Administration for Market Regulation. Carbon emissions are from the China Carbon Accounting Database (CEADs). Other data are from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook, the People’s Bank of China, and the Wind database.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for the variables are shown in Appendix B.

Results

Results of direct impacts

Univariate regression

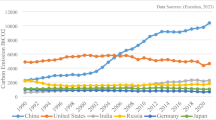

Figure 2 shows the scatterplot and univariate regression line of the level of CFTI and EPP. It demonstrates a relatively clear inverted ‘U’ relationship between administrative penalties and CFTI. As administrative penalties increase, the level of CFTI first increases and then decreases.

Multivariate regression

Controlling for year-fixed effects and city-fixed effects, we estimate Eq. (1) with CFTI as the dependent variable and EPAP as the independent variable with progressively increasing control variables, and we estimate Eq. (1) with the fixed effects model FE, and the results are shown in Table 1. Table 1 shows that the coefficients of the secondary terms of EPP are significantly negative at the 1% or 5% significance level, while the coefficients of the primary terms are significantly positive. This indicates a significant inverted “U” non-linear relationship between EPP and the level of CFTI. Our nonlinearity test using utest based on the estimation in column (5) shows that the null hypothesis of the linear or U-shaped relationship between EPAP and CFTI is rejected (p-value = 0.0175). The inflection point calculated by column (5) is 0.7194. Therefore, the relationship between EPAP and CFTI is inverted U-shaped. The empirical results support hypothesis H1. According to Table B1, the mean of EPAP is 0.1222, and the maximum value is 1.3165. Therefore, from a national perspective, environmental penalties are still in the stage of promoting CFTI, but the maximum value has exceeded the turning point, indicating that some cities have entered the stage of suppressing CFTI.

Environmental penalties are an important environmental regulatory measure. Du et al. (2021)73, Johnstone et al. (2010)74, and Jaffe& Palmer (1997)16 found that environmental rules can facilitate firms to increase R&D investment, which in turn facilitates green technological innovation. Lee et al. (2011)17 argued that government intervention through technology regulation can drive firms to invest in technological innovation, and automakers and component suppliers in the U.S. have innovated to introduce more advanced emission control technologies for automotive applications. Ouyang (2020)75, on the other hand, found that in the short term, environmental regulations have an “offsetting effect” on the research and innovation capacity of China’s industrial sector, and that the deepening of environmental regulations has forced the sector to reduce pollution control costs by improving the technological innovation capacity to reduce the cost of pollution control. Therefore, the relationship between environmental regulation and firm innovation is positively “U-shaped” and nonlinear. Based on signaling theory and challenge/threat theory, we find an inverse “U” shaped nonlinear relationship between EPP and CFTI using city-level macro data. This finding is relatively novel. In addition, based on the challenge/threat theory, Zhang et al. (2020)35found that the pressure generated by consumers’ awareness of the rule of law leads to an inverted U-shaped nonlinear relationship between consumers’ awareness of the rule of law and the level of fintech innovation. To some extent, our study is consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. (2020)35. In addition, political stability is conducive to the transition of economies towards clean energy76, thereby promoting CFTI from the demand side. A politically stable government will pay more attention to environmental and livelihood issues, and thus actively implement environmental penalties. The formulation of environmental regulations can promote the transformation of economies towards green electricity77, and in this process, CFTI will be derived. Therefore, our conclusion is somewhat consistent with the conclusion of Xu et al.

Robustness checks

Robustness tests, which addressed endogeneity, varied the measures of CFTI and EPP, controlled for mediating variables, and altered the estimation method, confirmed the robustness of the conclusion for H1. The results of these tests are presented in Appendix C.

Results based on the channels of the digital economy

The relationship between EPP, the development level of the digital economy, and the level of innovation in climate-friendly technologies is detailed in Appendix D.1.

With DECO as the mediator variable and EPAP as the independent variable, we use FE to estimate Eq. (2), and the results are shown in Table 2 Panel A column (1). Replacing the independent variable with rEPAP, we use FE to estimate Eq. (2), and the results are shown in Table 2 Panel A column (2). Fintech promotes the digital economy12, we control for the level of fintech development (FTCH) and use FE to estimate Eq. (2), which results in column (3) of Table 2 Panel A. To rule out endogeneity, we refer to Sect. “Results based on channels of fintech action” and use IV to estimate Eq. (2) based on the instrumental variables in Sect. “Results based on channels of fintech action”, which results in column (4) of Table 2 Panel A. From Table 2 Panel A, there is an inverted “U”-shaped non-linear relationship between EPP and the level of digital economy development.

We use CFTI as the dependent variable, DECO as the mediator variable, and EPAP as the independent variable, and we use FE to estimate Eq. (3), which results in column (1) of Panel B of Table 2. We use the year-end number of post offices in a city (ivDEFN) as an instrumental variable. In the digital economy’s early stages, urban and rural residents in China primarily used telephones at post offices for communication and early internet access. A higher number of post offices typically indicated more developed early-stage digital economies in cities. The development of the digital economy has a certain degree of inertia. Therefore, the number of post offices at the end of the year in a city ivDEFN is correlated with DECO, and ivDEFN satisfies the “correlation” condition. In addition, the number of telephones operated by the post office can hardly influence firms to implement CFTI, and ivDEFN satisfies the “exogeneity” condition. For this reason, based on the instrumental variables in Sect. “Results based on channels of fintech action”, together with ivDEFN, we estimate Eq. (3) using IV. Then, we conduct a weak instrumental variable test using weakiv. The results show that the chi-square statistic of the AR test is 24.02, p < 0.0001; and the chi-square statistic of the Wald test is 17.61, p = 0.0005. Therefore, ivEPAP, ivEPAP2, and ivDEFN rejected the hypothesis of weak instrumental variables, and ivEPAP, ivEPAP2, and ivDEFN are valid instrumental variables.

With CFTI as the dependent variable and ivEPAP, ivEPAP2, and ivDEFN as instrumental variables, we re-estimated Eq. (3) using the instrumental variable method (IV), and the results are shown in Table 2 Panel B column (2). Dependent variables were replaced with rCFTI, and we used FE to estimate Eq. (3), and the results are shown in Table 2 Panel B column (3). The independent variable is replaced with rEPAP and we use the FE estimating Eq. (3), which results in column (4) of Table 2 Panel B. From Table 2 Panel B, digital economic development favors CFTI.

Table 2 Panel A and Panel B show that there is an inverted “U”-shaped nonlinear relationship between EPP and the level of development of the digital economy, with the latter favoring CFTI. Therefore, hypothesis H2 is valid and robust.

Results based on channels of fintech action

The relationship between EPP, fintech, and the level of innovation in climate-friendly technologies is shown in Appendix D.2.

Using FTCH as the mediator variable and EPAP as the independent variable, we applied FE to estimate Eq. (2). The results are displayed in Table 3, Panel A, column (1). Substituting EPAP with rEPAP, we use FE to estimate Eq. (2), and the results are shown in Table 3 Panel A column (2). The digital economy promotes fintech development (Chen et al., 2022b), we control for the level of development of the digital economy (DECO), and we use FE to estimate Eq. (2), which results in Table 3 Panel A column (3). To rule out endogeneity, we refer to Sect. “Results based on channels of fintech action” and use IV to estimate Eq. (2) based on the instrumental variables in Sect. “Results based on channels of fintech action”, resulting in Table 3 Panel A column (4). From Table 3 Panel A, there is an inverted “U” shaped non-linear relationship between EPP and the level of fintech development.

We use CFTI as the dependent variable, FTCH as the mediator variable, and EPAP as the independent variable, and we use FE to estimate Eq. (3), which results in column (1) of Panel B of Table 3. As outlined in Sect. 4.3.1, we computed the natural logarithm of the average fintech development in other cities within the same year to derive the instrumental variable ivFTCH. For this analysis, we combined ivFTCH with the instrumental variables from Sect. “Results based on channels of fintech action” to estimate Eq. (3) using the IV method. Then, we conduct a weak instrumental variable test using weakiv. The results show that the chi-square statistic of the AR test is 43.44, p < 0.0001; and the chi-square statistic of the Wald test is 19.45, p = 0.0002. Therefore, ivEPAP, ivEPAP2, and ivFTCH reject the hypothesis of weak instrumental variables, and ivEPAP, ivEPAP2, and ivFTCH are valid instrumental variables.

With CFTI as the dependent variable and ivEPAP, ivEPAP2, and ivFTCH as instrumental variables, we re-estimated Eq. (3) using the instrumental variable method (IV), and the results are shown in Table 3 Panel B column (2). Dependent variables were replaced with rCFTI, and we estimated Eq. (3) using FE, and the results are shown in Table 3 Panel B column (3). The independent variable is replaced with rEPAP and we use FE to estimate Eq. (3), which results in column (4) of Table 3 Panel B. From Table 3 Panel B, FinTech development favors CFTI.

Table 3 Panel A and Panel B show that there is an inverted “U” nonlinear relationship between EPP and the level of fintech development, with the latter favoring CFTI. Therefore, hypothesis H3 is valid and robust.

Conclusion, implications, and outlook

Conclusion

Our paper studies the impact of administrative penalties on CFTI. We theoretically analyze the path of EPP affecting CFTI in terms of direct and indirect effects. Based on data from 281 Chinese cities from 2008 to 2020, we tested this using a city and year two-way fixed effects model. We found that the relationship between EPP and CFTI is an inverted “U”-shaped nonlinear relationship, and the impact of EPP on CFTI is more complicated. In addition, EPP also affects CFTI through the digital economy and financial technology, and a non-linear relationship exists between the impact mechanisms as well.

Our paper conducted research based on the actual situation in China. Unlike federal countries such as the United States, China is a unitary state. This means that after the central government establishes an action plan, local governments will actively implement the action plan according to the deployment of the central government. In order to achieve better political achievements, local governments will also compete to implement the action plan, without any negative or negligent situations. In terms of environmental quality, after the central government established the “Blue Sky and White Cloud Defense Campaign” action plan, local governments have focused on improving the environment and increasing environmental penalties in order to improve environmental quality as soon as possible. In this way, local governments in various cities will increase the implementation of environmental penalties, and physical and financial enterprises within the city cannot avoid the pressure brought by environmental penalties through relocation and other means. On the contrary, for federal countries, local governments have greater autonomy and may not necessarily act in unison. In this way, companies can avoid the pressure brought by environmental penalties by relocating and other means. Therefore, the research conclusions of this article have better reference significance for unitary countries, but may not be applicable to federal countries.

Revelations

Our findings have the following theoretical and practical implications. First, our findings imply that environmental penalties should be moderate for policy makers.Climate-friendly technologies can mitigate or adapt to climate change6,7, which has positive implications for combating global climate change. Our study finds an inverted “U”-shaped non-linear relationship between EPP and CFTI. This implies that to promote CFTI, governments should follow the principle of “moderation” when implementing environmental regulations and imposing EPP. As such, it is advisable not to excessively increase penalties to promote CFTI. Second, our findings provide new evidence for countries to promote the development of the digital economy. Digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence and big data, are the technological drivers of the digital economy, and many countries, including China, have introduced many policies to promote the development of the digital economy, especially policies to promote the development of digital technologies. Our study finds that EPP also influence the digital economy’s development, exhibiting an inverted ‘U’-shaped non-linear effect. This implies that environmental authorities in all countries also have a responsibility to promote the digital economy and need to consider the impact on the digital economy when imposing EPP. Finally, our study provides new evidence for countries to promote fintech development. Fintech is expected to reconfigure the global financial system and is the focus of future competition among countries. For this reason, both developed countries and a wide range of developing countries are promoting fintech development. Our study finds that EPP has an inverted “U”-shaped non-linear effect on fintech. This means that the promotion of FinTech is not only the responsibility of financial regulators, but also the EPP imposed by the environmental protection authorities have an impact on FinTech. Therefore, to promote the development of fintech, financial regulators need to establish a communication and coordination mechanism with environmental protection departments to prevent EPP from lowering the level of fintech development.

Outlook

There may be other pathways for the effect of EPP on CFTI, which we did not study. This is the shortcoming of this paper and one of the future research directions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Barrett, K. L., Lynch, M. J., Long, M. A. & Stretesky, P. B. Monetary penalties and noncompliance with environmental laws: a mediation analysis. Am. J. Crim. Justice 43, 530–550 (2018).

Chen, X. & Zhan, M. Does environmental administrative penalty promote the quantity and quality of green technology innovation in China? Analysis based on the peer effect. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1070614 (2022).

Aproskie, J. & Goga, S. I. Administrative penalties-impact and alternatives. J. Econ. Fin. Sci. 4, 133–146 (2011).

Heyes, A. Implementing environmental regulation: enforcement and compliance. J. Regul. Econ. 17(2), 107–129 (2000).

Dong, H. Why does environmental compliance cost more than penalty? —A legal analysis on environmental acts of enterprises in China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 1, 434–442 (2007).

Nguyen, Q. L., Nguyen, M. H., La, V. P., Bhatti, I. & Vuong, Q. H. Enterprise’s strategies to improve financial capital under climate change scenario–evidence of the leading country. Npj Climate Act. 3, 38 (2023).

Carattini, S., Levin, S. & Tavoni, A. Cooperation in the climate commons. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 13(2), 227–247 (2019).

Fischer, C., Torvanger, A., Shrivastava, M. K., Sterner, T. & Stigson, P. How should support for climate-friendly technologies be designed?. Ambio 41, 33–45 (2012).

Otte, P. P. What makes people act climate-friendly? A decision-making path model for designing effective climate change policies. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 52, 132–139 (2021).

Lu, J., Yang, S. & Ma, C. Fiscal decentralization, financial decentralization and technological innovation. South China J. Econ. 06, 36–50 (2021).

Li, Z. & Yang, S. Fiscal decentralization, government innovation preferences and regional innovation efficiency. J. Manag. World 34(12), 29–42 (2018).

Chen, X., Teng, L. & Chen, W. How does FinTech affect the development of the digital economy? Evidence from China. North Am. J. Econ. Finance 61, 101697 (2022).

Chen, X. Information moderation principle on the regulatory sandbox. Econ. Change Restruct. 56(1), 111–128 (2023).

Spence, M. l. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355-374. (The MIT press, 1973).

Lazarus, R. S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 46(8), 819–834 (1991).

Jaffe, A. B. & Palmer, K. Environmental regulation and innovation: a panel data study. Rev. Econ. Stat. 79(4), 610–619 (1997).

Lee, J., Veloso, F. M. & Hounshell, D. A. Linking induced technological change, and environmental regulation: Evidence from patenting in the US auto industry. Res. Policy 40(9), 1240–1252 (2011).

Kneller, R. & Manderson, E. Environmental regulations and innovation activity in UK manufacturing industries. Resour. Energy Econ. 34(2), 211–235 (2012).

Chen, Z., Kahn, M. E., Liu, Y. & Wang, Z. The consequences of spatially differentiated water pollution regulation in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 88, 468–485 (2018).

Zou, W. Can environmental regulation promote urban green innovation?. Econ. Survey 40(02), 24–33 (2023).

Carattini, S., Gosnell, G. & Tavoni, A. How developed countries can learn from developing countries to tackle climate change. World Dev. 127, 104829 (2020).

Halleck-Vega, S., Mandel, A. & Millock, K. Accelerating diffusion of climate-friendly technologies: A network perspective. Ecol. Econ. 152, 235–245 (2018).

Golombek, R. & Hoel, M. International cooperation on climate-friendly technologies. Environ. Resour. Econ. 49, 473–490 (2011).

Xu, R., Farooq, U., Alam, M. M. & Dai, J. How does cultural diversity determine green innovation? New empirical evidence from Asia region. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 106, 107458 (2024).

Ding, X. & Shahzad, M. Effect of environmental penalties on the cost of equity-the role of corporate environmental disclosures. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 31(2), 1073–1082 (2022).

Zheng, X. Introspections and suggestions on the amount fixing of administrative penalty for environmental pollution. Comput. Water Energy Environ. Eng. 2(2), 56–60 (2013).

Chen, X. & Zhang, H. How does city group risk-taking affect climate-friendly technology innovation in cities? Evidence from China. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2025.23366 (2025).

Yu, Y., Xia, L. & Duan, S. Market regulation and enterprise growth: Empirical analysis based on administrative penalties data. China Ind. Econ. 08, 118–136 (2023).

Stiglitz, J. E. Information and the change in the paradigm in economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 92(3), 460–501 (2002).

Saxton, G. D., Gómez, L., Ngoh, Z., Lin, Y. P. & Dietrich, S. Do CSR messages resonate? Examining public reactions to firms’ CSR efforts on social media. J. Bus. Ethics 155, 359–377 (2019).

Ernst, B. A. et al. Virtual charismatic leadership and signaling theory: A prospective meta-analysis in five countries. Leadersh. Q. 33(5), 101541 (2022).

Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 87(3), 355–374 (1973).

Mirowska, A. & Mesnet, L. Preferring the devil you know: Potential applicant reactions to artificial intelligence evaluation of interviews. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 32(2), 364–383 (2022).

Bafera, J. & Kleinert, S. Signaling theory in entrepreneurship research: A systematic review and research agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 47, 10422587221138488 (2022).

Zhang, H., Chen, X. & Liu, C. Consumers’ awareness of the rule of law: Promoting orconstraining FinTech innovation in China——evidence from P2P network loan. Econ. Theory Business Manag. 10, 65–82 (2020).

Mitchell, M. S., Greenbaum, R. L., Vogel, R. M., Mawritz, M. B. & Keating, D. J. Can you handle the pressure? The effect of performance pressure on stress appraisals, self-regulation, and behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 62(2), 531–552 (2019).

Martin, A. J. et al. Challenge and threat appraisals in high school science: Investigating the roles of psychological and physiological factors. Educ. Psychol. 41(5), 618–639 (2021).

Putwain, D. W., Symes, W. & Wilkinson, H. M. Fear appeals, engagement, and examination performance: The role of challenge and threat appraisals. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 87(1), 16–31 (2017).

Aydın, M. & Sarı, İ. The relationship between coach-created motivational climate and athletes’ challenge and threat perceptions. Qual. Sport 7(2), 24–37 (2021).

Lazarus, R. S. & Alfert, E. Short-circuiting of threat by experimentally altering cognitive appraisal. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 69(2), 195–205 (1964).

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (Springer publishing company, 1984).

Jones, M., Meijen, C., McCarthy, P. J. & Sheffield, D. A theory of challenge and threat states in athletes. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2(2), 161–180 (2009).

Turner, M. J., Jones, M. V., Sheffield, D., Barker, J. B. & Coffee, P. Manipulating cardiovascular indices of challenge and threat using resource appraisals. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 94(1), 9–18 (2014).

Tomaka, J., Blascovich, J., Kibler, J. & Ernst, J. M. Cognitive and physiological antecedents of threat and challenge appraisal. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 73(1), 63–72 (1997).

Vail, K. E. III., Reed, D. E., Goncy, E. A., Cornelius, T. & Edmondson, D. Anxiety buffer disruption: Self-evaluation, death anxiety, and stressor appraisals among low and high posttraumatic stress symptom samples. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 39(5), 353–382 (2020).

Loewenstein, K., Barroso, J. & Phillips, S. The experiences of parents in the neonatal intensive care unit: an integrative review of qualitative studies within the transactional model of stress and coping. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 33(4), 340–349 (2019).

Wormwood, J. B. et al. Physiological indices of challenge and threat: A data-driven investigation of autonomic nervous system reactivity during an active coping stressor task. Psychophysiology 56(12), e13454 (2019).

Wright, R. A. & Kirby, L. D. Cardiovascular correlates of challenge and threat appraisals: A critical examination of the biopsychosocial analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 7(3), 216–233 (2003).

Mansell, P. C. Stress mindset in athletes: Investigating the relationships between beliefs, challenge and threat with psychological wellbeing. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 57, 102020 (2021).

Moore, L. J., Vine, S. J., Wilson, M. R. & Freeman, P. The effect of challenge and threat states on performance: An examination of potential mechanisms. Psychophysiology 49(10), 1417–1425 (2012).

Majeed, M. & Naseer, S. Is workplace bullying always perceived harmful? The cognitive appraisal theory of stress perspective. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 59(4), 618–644 (2021).

Seery, M. D., Weisbuch, M., Hetenyi, M. A. & Blascovich, J. Cardiovascular measures independently predict performance in a university course. Psychophysiology 47(3), 535–539 (2010).

Fichman, R. G., Dos Santos, B. L. & Zheng, Z. Digital innovation as a fundamental and powerful concept in the information systems curriculum. MIS Q. 38(2), 329-A15 (2014).

Nambisan, S., Lyytinen, K., Majchrzak, A. & Song, M. Digital innovation management: reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Q. 41(1), 223–238 (2017).

Ding, H., & Cheng, Q. Digital innovation, entrepreneurship and green development of manufacturing enterprises. Science Research Management: 1–14. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1567.G3.20231016.0918.006.html. (2023).

Cheng, X. & Chen, X. The digital economy and power consumption: empirical analysis based on consumption intensity in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26, 1–23 (2023).

Chen, X., Chen, W. & Lu, K. Does an imbalance in the population gender ratio affect FinTech innovation?. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 188, 122164 (2023).

Loebbecke, C. & Picot, A. Reflections on societal and business model transformation arising from digitization and big data analytics: A research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 24(3), 149–157 (2015).

Chen, X. & Zhang, H. Taoism and green technology innovation: evidence from China. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 37, 1–14 (2023).

Cyron, T., Steigenberger, N. & Achtenhagen, L. The construction of social performance in digital communication channels. In Academy of Management Proceedings (eds Cyron, T. et al.) (Briarcliff Manor, 2019).

Cong, L. W., Xie, D. & Zhang, L. Knowledge accumulation, privacy, and growth in a data economy. Manag. Sci. 67(10), 6480–6492 (2021).

Duan, D. & Feng, Z. The impact of digital development on low carbon green performance in countries along the belt and road. Inquiry Econ. Issues 05, 158–176 (2023).

FSB. Fintech: Describing the landscape and a framework for analysis. https://www.fsb.org/. (2016).

Cheng, X., Yao, D., Qian, Y., Wang, B. & Zhang, D. How does fintech influence carbon emissions: Evidence from China’s prefecture-level cities. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 87, 102655 (2023).

Firdousi, S. F., Afzal, A. & Amir, B. Nexus between FinTech, renewable energy resource consumption, and carbon emissions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(35), 84686–84704 (2023).

Tao, R., Su, C. W., Naqvi, B. & Rizvi, S. K. A. Can Fintech development pave the way for a transition towards low-carbon economy: A global perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 174, 121278 (2022).

Cong, L. W. & He, Z. Blockchain disruption and smart contracts. Rev. Fin. Stud. 32(5), 1754–1797 (2019).

Di Castri, S., & Plaitakis, A. Going beyond regulatory sandboxes to enable FinTech innovation in emerging markets. SSRN 3059309. (2018).

Ryu, H. S. What makes users willing or hesitant to use Fintech?: the moderating effect of user type. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 118(3), 541–569 (2018).

Fuster, A., Plosser, M., Schnabl, P. & Vickery, J. The role of technology in mortgage lending. Rev. Fin. Stud. 32(5), 1854–1899 (2019).

Xu, R., Chen, X. & Dong, P. Nexus among financial technologies, oil rents, governance and energy transition: Panel investigation from Asian Economies. Resour. Policy 90, 104746 (2024).

Li, C. T., Yan, X. W., Song, M. & Yang, W. Fintech and corporate innovation——evidence from Chinese NEEQ-listed companies. China Ind. Econ. 01, 81–98 (2020).

Du, K., Cheng, Y. & Yao, X. Environmental regulation, green technology innovation, and industrial structure upgrading: The road to the green transformation of Chinese cities. Energy Econ. 98, 105247 (2021).

Johnstone, N., Haščič, I. & Popp, D. Renewable energy policies and technological innovation: evidence based on patent counts. Environ. Resour. Econ. 45, 133–155 (2010).

Ouyang, X., Li, Q. & Du, K. How does environmental regulation promote technological innovations in the industrial sector? Evidence from Chinese provincial panel data. Energy Polic. 139, 111310 (2020).

Xu, R., Murshed, M. & Li, W. Does political (De) stabilization drive clean energy transition?. Politická Ekonomie 72(2), 357–374 (2024).

Xu, R., Pata, U. K. & Dai, J. Sustainable growth through green electricity transition and environmental regulations: do risks associated with corruption and bureaucracy matter?. Politická Ekonomie 72(2), 228–254 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Lanyue Zhang, Hongwei Zhang. Data curation: Hongwei Zhang. Formal analysis: Lanyue Zhang, Hongwei Zhang. Funding acquisition: Lanyue Zhang, Hongwei Zhang. Methodology: Lanyue Zhang, Hongwei Zhang. Resources: Lanyue Zhang, Hongwei Zhang. Software: Lanyue Zhang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Zhang, H. & Yang, Q. A study on the promoting effect of environmental penalties on climate-friendly technological innovation in China. Sci Rep 15, 36143 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11939-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11939-2