Abstract

Silver nanoparticles (Ag°/glucose) were synthesized based on glucose as a natural reducing agent, aiming to develop an eco-friendly catalytic system. The characteristics of the produced Ag°/glucose were confirmed using standard nanomaterial characterization techniques. The optimum conditions for eliminating p-nitrophenol (PNP) and methylene blue (MB) from artificial polluted water using Ag°/glucose were systematically explored. Various kinetic and isotherm models were applied to elucidate the sorption mechanism and behavior. The synthesized Ag°/glucose exhibited a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak at 430 nm, with an average particle size ranging from 21 to 31 nm, and a zeta potential recorded as − 16 mV. The final concentration of Ag°/glucose was determined to be 1.2 × 10− 6 mol/L. During the first 15 min of incubation, a dose of 20 µL/mL Ag°/glucose achieved 53% and 74% removal of the targeted PNP and MB, respectively. Increasing the dose to 30 µL/mL showed a complete removal of both pollutants. Kinetic analysis revealed that the pseudo-second-order model was the best fitting model for both PNP and MB adsorption processes. Isothermal data showed a superior appropriateness of the present results to the Langmuir and Freundlich model for describing sorption behavior, with maximum adsorption capacities (qmax) of 2.5 E + 3and 1.0 E + 3 mg/g for PNP and MB, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing progress of industrialization and rapid urban development, a growing volume of hazardous wastewater is being discharged into the environment, particularly into water bodies, with minimal or no treatment. Clean water is essential for sustaining life; however, maintaining its quality for various applications has become increasingly challenging due to the significant amounts of waste generated from industrial, municipal, and residential sources1. Recently, the discharge of organic dyes and nitro compounds into aquatic environments has emerged as a significant environmental concern, as these toxic chemicals pose a serious threat to all forms of life on the planet. Furthermore, dyes like MB are examples of non-biodegradable organic pollutants that have an adverse effect on water quality by producing an unpleasant odor, blocking light penetration, raising the demand for chemical oxygen, lowering the concentration of dissolved oxygen, and ultimately killing aquatic life2. Therefore, efficient and pointed manners for removing organic dyes from water systems is a critical worldwide concern for treating wastewater3. Also, one of the worst types of organic contaminants originating from industrial and agricultural activities is the p-nitrophenol (PNP), which is listed by the US Environmental Protection Agency4,5 as one of 129 compounds that may cause cancer.

Reverse osmosis, photochemical, biological, coagulation-flocculation, chemical oxidation, adsorption, membrane separation, electrochemical, aerobic, and anaerobic microbial degradation are some of the different techniques for removing organic pollutants. Adsorption is the most successful physicochemical technique for eliminating organic pollutants from wastewater, hence it involves using of a variety of sorbed materials1,6,7.

In the environmental pollution domain, nanotechnology has several applications, such as cleanup, monitoring, detection, and prevention8. Nanomaterials can be used to get rid of these pollutants because of their unique properties. This technology is inexpensive, safe, and ecologically benign. Numerous research on the potential of nanomaterials for water body remediation has been conducted recently. Many promising nanoparticles, including nickel oxide9 carbon nanotubes10 silver nanoparticles6 and zero-valent iron11 have been employed in wastewater treatment.

Compared to those of typical materials, nanostructures, especially silver nanoparticles, have a larger surface area, which enhances their potential for environmental remediation and lowers the overall cost of eliminating pollutants12,13. Therefore, silver nanoparticles are excellent catalysts for a variety of catalytic reduction processes14,15.

Silver nanoparticles were synthesized according to different reduction approaches, depending on chemicals, physical, or green reducing agents like plant extract, ascorbic acid, sodium borohydride, hydrazine, sodium citrate, glucose, and polyvinyl alcohol. The presence of natural antioxidants, such as alkaloids, phenols, citric acid, polyphenols, terpenes, ascorbic acid, flavonoids, proteins, amino acids, carbohydrates, saponins, flavonoids, chromones, steroids, saturated-unsaturated fatty acids, terpenoids, and other components, is crucial for the synthesis process, and essential for improving the physical and chemical properties of the Ag nanoparticles16,17,18, –19. This is one of the most important reasons for the efficiency variances of different formulas in their catalytic activities. For example, green silver nanoparticles observed successful removing for methylene blue and p-nitrophenol4,20 methyl orange, methyl red, and congo red21 and hexavalent chromium6 from contaminated water.

In the present study, silver nanoparticles were greenly synthetized depending on D-glucose for reducing silver ions to metallic silver, and through this process, it oxidizes itself to gluconic22,23. Here, the present study aimed to: (1) greenly synthesis Ag° using glucose as a natural reductant, (2) examine the Ag°/glucose catalytic activity and figured out the optimum operating conditions for removing PNP and MB, and (3) conducting kinetic and isothermal studies to explore the removal mechanism and behavior.

Materials and methods

Ag°/glucose green synthesis and characterization

Ag°/glucose was synthesized using the procedure previously outlined by Darroudi et al.22 as follows: (1) 1% gelatin was dissolved in 10 mL of AgNO3 (1 M) solution. (2) 10 mL of NaOH (1 M) was added to the AgNO3/ gelatin solution, (3) 10 mL of a glucose solution (2 M) was added to the mixture after it had heated up to 60 °C, and the reaction was then allowed to proceed for 15 min.

Several routine tests were conducted to confirm the success of the green synthesis process21:

-

1.

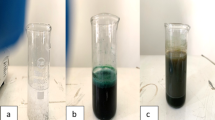

Primarily, the reduction process was seen visually by observing the color shift from yellow to brownish yellow to deep brown.

-

2.

An Alpha 1502 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Laxco, Inc., Bothell, WA 98021, USA) was used to scan the obtained Ag°/glucose at 50 nm intervals between 250 and 750 nm in order to verify the reduction process.

-

3.

Using scanning electron microscopy (MODEL JSM-IT200), the Ag°/glucose surface shape and particle size were investigated and characterized.

-

4.

FTIR spectroscopy was used to investigate the chemical components that led to the reduction of silver ions and the capping agent of silver nanoparticles (PerkinElmer Spectrum IR Version 10.6.0).

-

5.

The Ag°/glucose zeta potential was examined using the Malvern Zeta Sizer.

-

6.

The Ag°/glucose final concentration was theoretically calculated24.

Batch sorption experiments

The best operating parameters for removing PNP (99% purity) and MB (70% purity) in a single liquid state from artificially polluted water by employing Ag°/glucose as a sorbent material were investigated by a set of sorption studies3,20,25. In these tests, the concentration of pollutants (2, 5, and 10 µg/ml) was examined, along with the contact time (15–60 min) and Ag°/glucose dose (10, 20, and 30 µL/mL). Every test was conducted three times, and the mean values were used as the results. For the PNP samples, 300 µL/mL NaBH4 (0.5 mM) was added. The PNP and MB removal percentages (Eq. 1) and quantity of sorbed pollutant (Eq. 2) were determined using a UV–Visible spectrophotometer at 400 and 665 nm, respectively, and calculated according to equations illustrated in Table 1.

Kinetics model-based data analysis

Four kinetic models (Table 1) were used to properly explain the PNP and MB adsorption mechanism: the pseudo-first order (Eq. 3), pseudo-second order (Eq. 4), Elovich (Eq. 5), and intra-particle diffusion (Eq. 6) models26,27. Since the adsorption features of both pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order methods partially explain the adsorption mechanism, they do not offer sufficient systematic values. Considering the complexity of the kinetic process, it is necessary to evaluate several models, particularly the Elovich model and intra-particle diffusion, in order to get an accurate and thorough assessment of the entire kinetic investigation28,29,30,31.

Isothermal model-based data analysis

In this section the PNP and MB sorption equilibrium data were applying to the linear form of three isothermal models (Table 1): Langmuir (Eq. 7), Freundlich (Eq. 8), and Temkin (Eq. 9) adsorption isotherm models allowed for the provision of important insights into the surface properties and affinity of the sorbent6.

Results and discussion

Ag°/glucose synthesis and characterization

Ag°/glucose nanoparticles were synthesized using a natural polymeric matrix, silver nitrate (silver precursor), gelatin (stabilizer), glucose (redacting agent), and sodium hydroxide (accelerator). Once silver ions were distributed throughout the gelatin matrix, the process of reduction was carried out as follows: gelatin reacted with Ag+ to create a stable silver-gelatin complex [Ag(gel)]+, which then reacted with OH− to form silver metal because the reduction of silver ions was caused by the oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid22. This mechanistic insight was explained other studies, colloidal silver nanoparticles was synthesized using ‘green’ reducing agents either from different types of honey, or β-d-glucose. They explain the mechanism of the synthesis process as follows reduction of Ag + is assisted by the addition of NaOH. The alkaline environment facilitates the opening of the glucose ring by the abstraction of the α-proton of the ring oxygen, and following glucose is oxidized to gluconic acid32. Also, glucose can be oxidized to gluconic acid and reduce silver cations to AgNPs in an alkaline medium, and this mechanism is accelerated by heating33. As mentioned by Darroudi et al.22 the possible chemical equation for preparing the Ag-NPs is:

Surface plasmon resonance data from the spectroscopic scan (Fig. 1a) and visual inspection were utilized to verify the synthesis and stabilization of the green-synthesized Ag°/glucose. Previous studies observed changes in the color of Ag° colloidal solutions from yellow to dark brown due to the excitement of Ag° surface plasmon resonance. Such color transformation indicates a uniform dispersion of spherical Ag° particles34,35 where the absorption peaks ought to be situated between 400 and 450 nm21. A sharp plasmon with a λmax at 430 nm appeared for the synthetized Ag°/glucose nanoparticles, is reported. Ag°/glucose’s surface morphology was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) at a magnification of 35,000X and a 500 nm scale (Fig. 1b). The results demonstrated that the particle sizes of Ag°/glucose ranged from 21 to 31 nm, and the morphology form was almost spherical shape. The surface potential known as zeta potential is linked to the surface electrical charge and influences various aspects of material particles in suspension, such as surface contact, precipitation, and particle complexation36. The zeta potential of Ag°/glucose was recorded using Malvern Zeta Sizer instrument to measure the effective electric charge on the nanoparticle surface. Whereas, the zeta potential value is a crucial particles characteristic as it can influence both particles stability and properties. Theoretically, more pronounced zeta potential values, being positive or negative, tend to stabilize particle suspension. The electrostatic repulsion between particles with the same electric charge prevents the aggregation of the sphere37,38,39.

The recent data (Fig. 1c) showed that the Ag°/glucose nanoparticles have a negative surface charge of − 16mV. Remarkably, Ag°/glucose’s negative charge and ability to stabilize dispersed particles while preventing the formation of aggregates or precipitations seem to make it advantageous for uptake of cationic contaminants such as PNP and MB40. The FTIR spectrum of D-glucose shows the existence of a strong and broad absorption peak at 3391 cm− 1indicating the presence of v(OH) group stretching vibration. A small peak at 2920 cm− 1 was attributed to the absorption peak of v(CH2) group, and the bands at 1475 cm− 1 and 1328 cm− 1 were assigned to the bending vibration of v(CH). The v(C–O) and v(C–C) stretching bands were observed at 1132 and 1007 cm− 1, respectively41. While after the green synthesis of Ag°/glucose the FTIR spectrum shows different peaks at 3879.83, 3846.88, 3725.18, 3398.68, 2929.67, 1640.66, 1383.90, 1075.44, 1034.11, and 563.68 cm− 1 (Fig. 1d).

p-nitrophenol and methylene blue removal

The two studied organic aromatic compounds PNP and MB have significant harmful effects on the aquatic ecosystem. As these compounds are essential to produce numerous medications, insecticides, phytochemicals, synthetic colors, and pharmaceutical raw materials, they are widely utilized and dispersed in laboratories and industrial processes. Because such compounds are difficult to decompose, even extremely low concentrations of them pose substantial hazards to aquatic habitats42. In this study, the effects of different major parameters (Ag°/glucose dose, contact time, and pollutant concentrations) on either PNP or MB removal efficiency from synthetic contaminated water were extensively investigated.

Effect of Ag°/glucose dose

The operating conditions were: pollutant concentration is 10 µg/mL, contact time is 30 min, and temperature is maintained at the ambient room temperature (22° C). The Ag°/glucose nanoparticles doses were 10, 20, and 30 µl/mL from the liquid formula. Increasing Ag°/glucose dose from 10 to 30 µl/mL raised the PNP removal percentages from 30 up to 100% (Fig. 2a) and from 46 to 100% when MB is the target (Fig. 2b). The earlier research clarifies increasing in pollutant removal percentage with increasing Ag°/glucose dose occurred because a greater mass provided more active sites for bio-sorption43,44. Also, increasing the Ag°/glucose dose may be causing a rise in active surfaces that are available for use as adsorption sites45,46. From the data in the current section, 20 µL/mL Ag°/glucose liquid formula was chosen as the adsorbent dose for further experiments.

Effects of the contact time on the removal potency

The operating conditions were: pollutant concentration is 10 µg/mL, contact time from 15 to 60 min, Ag°/glucose dose is 20 µL/mL, and temperature maintained at the ambient room temperature. During the first 15 min, the optical density of the PNP (Fig. 3a) and MB (Fig. 3b) solutions decreased remarkably because of the addition Ag°/glucose nanoparticles to the target contaminated samples. Thus, the incubation of pollutants for 15 min with Ag°/glucose would be the optimum contacting time and will be used for the remaining experiments. A lot of studies were conducting to assess the catalytic potentials of silver nanoparticles and they concluded that, PNP could be rapidly decreased by green silver nanoparticles4 also 98.3% of PNP was eliminated in 11 min when green nano silver was utilized25 silver nanoparticles have a useful catalytic ability to degrade and reduct PNP in the presence of aqueous sodium borohydride35 and in less than 5 min of incubation with silver nanoparticles greenly synthesized, by Hordeum vulgare L. could be suitable to eliminate the same two tested pollutants either in single or mixed states20.

Kinetic studies

Removal rates of the studied pollutants and their controlling mechanisms were examined at different ratios of sorbed/sorbent as part of the kinetics studies. Pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, and intra-particle diffusion kinetic models were employed to describe the mechanism of p-nitrophenol and methylene blue removal by Ag°/glucose. The parameters obtained for the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, and intra-particle diffusion kinetic models are presented in Table 2; Fig. 4a- f. The operating conditions used for the two target pollutants were Ag°/glucose doses of 10, 20, and 30 µl/mL; target pollutant (PNP or MB) concentrations of 2, 5, and 10 µg/mL; intervals ranging from 15 to 60 min; and temperature maintained at the ambient temperature.

The effects of Ag°/glucose concentrations (10, 20, and 30 µl/mL) on the PNP and MB kinetic parameters are presented in Fig. 4 (a & c), respectively, and Table 2. Depending on the R2 values, the most efficient results were recorded when the Ag°/glucose dose was 20 µl/mL. At such dose (20 µl/mL), pseudo-second order was the best fit kinetic model for the two tested pollutants (PNP and MB). Additionally, the similarities between the experimentally determined and calculated q values confirmed that the pseudo-second-order model effectively described the PNP and MB equilibrium kinetics.

The same kinetic mechanism was confirmed when PNP or MB was applied at different concentrations (2, 5, and 10 µg/mL), Table 2; Fig. 4 (b & d). These findings confirmed that the best-fit kinetic model was a pseudo-second-order model. The reliability of the kinetic models was determined by the coefficient value (R2), where the best fit model must have a R2 value closest to 1. Furthermore, the model effectively describes equilibrium kinetics, as evidenced by the similarities between the computed and experimental data1 as illustrated in Fig. (4 e & f). The sorption of PNP and MB onto Ag°/glucose appears to be limited by chemical sorption, which is influenced by the adsorbent’s active sites at room temperature, as indicated by the rise in total PNP and MB sorption in the pseudo-second-order model47. According to this model, which is consistent with the current data, a rapid response eventually finds equilibrium, followed by a sluggish reaction that can go on for a long time48. Many studies have been conducted to determine the best kinetic model for describing the absorption of PNP and MB, for example, for the absorption of MB by agar/κ-carrageenan hydrogels49 for the removal of PNP using activated biochar47and for the removal of PNP-MB mixtures by green silver nanoparticles20. These studies confirmed that the pseudo-second order is the most suitable kinetic model for removing MB and PNP, which is in agreement with the current findings. Furthermore, when the value of computed α > β in the Elovich model, the adsorption process proceeded more quickly than the desorption process50 which is consistent with our results (Table 2).

Pseudo-second-order plot: (a) effect of Ag°/glucose dose on PNP kinetic parameters, (b) effect of PNP concentration on PNP removal kinetic parameters, (c) effects of Ag°/glucose dose on MB kinetic parameters, and (d) effect of MB concentration on MB removal kinetic parameters. The dots represent the experimental data however the lines represent the Pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetic model. (e) Effects of time on the adsorption capacity of PNP (g/g), (f) Effects of time on the adsorption capacity of PNP (g/g). The error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Effect of initial pollutant concentrations

The relationship between concentrations of either PNP or MB and their removal percentages are presented in Fig. 5a & b, respectively. The operating conditions were contact time is 15 min, Ag°/glucose dose is 20 µl/mL, pollutant concentrations are 2, 5, and 10 µg/mL, and temperature maintained at ambient temperature. As shown in Figs. 5a & b, when the pollutants concentration increased from 2 to 10 µg/mL, the removal percentages decreased from 100 to 72 and 53% for PNP, and from 100 to 89 and 74% for MB. Similar findings were observed by Hassan et al.,51 and they provided the following explanation: at lower initial pollutant concentrations, there were relatively few pollutant molecules compared to the huge number of accessible active sites, which led to a quick uptake by the sorbent. However, a progressive decline in the proportion of removed pollutants was noted when the starting concentrations of pollutants increased; this could be because all possible active sites had been reached.

Isothermal studies

An explicit examination of the relationship between the concentration and sorbed amount of PNP or MB was done using the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Tempkin isothermal models. Parameters that were obtained from the plots are displayed in Table 3; Fig. 6. Based on the correlation coefficient (R2), the model that best explains the adsorption process was selected. The best-fit model for explaining the adsorption of PNP and MB on Ag°/glucose nanoparticles was the Langmuir isotherm, according to a comparison of R2 (1) PNP: Langmuir (0.997) > Tempkin (0.995) > Freundlich (0.958), (2) MB; Freundlich (0.999) > Langmuir (0.971) > Tempkin (0.964). According to an analysis of the Langmuir plot, the maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) for Ag°/glucose being 2500 and 10,000 mg/g for PNP and MB, respectively. The value of RL indicates the favorability of the adsorption and can be classified into three ranges: irreversible (RL = 0), linear (RL = 1), or unfavorable (RL > 1)6. Based on the current results (Table 3), the adsorption process was beneficial as indicated by the RL(PNP) = 0.141 and RL(MB) = 0.365.

A suggested removal mechanism

The impact of the interaction between the Ag°/glucose functional groups and the sorbed pollutants was investigated using FTIR analysis before and after sorption (Figs. 7 and 8). It was found that the Ag°/glucose’s primary functional groups were 3879.83, 3846.88, 3725.18, 3398.68, 2929.67, 1640.66, 1383.90, 1075.44, 1034.11, and 563.68 cm⁻¹. Hence, after PNP sorption, some peaks that represent O-H, N-H, C-H, C= N, and C-I groups at 2930, 3399, 3930, 1640.66, and 563.68 cm-¹ disappeared. This is explained by the structure of PNP, which has both a hydroxyl group and a nitro group on opposite sides of the benzene ring. These groups can form hydrogen bonds with oxygen-containing functional groups (like -OH groups) on the Ag°/glucose surface52. As well as the nitrogen atom in the N-H group on the Ag°/glucose surface can act as a hydrogen bond acceptor, while the hydrogen atom in the -OH group of PNP can act as a hydrogen bond donor53. Also, at certain pH levels, PNP can exist as a negatively charged phenolate ion. This can lead to electrostatic interactions with positively charged sites on the Ag°/glucose surface, including those associated with C = N groups54. Finally, the iodine atom in the C-I bond can be displaced by the oxygen atom of the phenolic group in p-nitrophenol through a nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction55. In the case of MB sorption, peaks representing O-H, N-H, C =N, C=C, N=C=S, C-Cl-, C-Br, and C-I disappear. Because MB is a cationic dye, when dissolved in water, it dissociates into a positively charged ion, and Ag°/glucose with negatively charged surfaces or functional groups containing nitrogen (like amines or amides) can attract and bind to the MB56. Additionally, the hydroxyl groups on the Ag°/glucose nanoparticles surface can form hydrogen bonds with MB molecules. This involves the sharing of hydrogen atoms between the hydroxyl group and specific atoms (nitrogen and sulfur) in the MB molecule57,58. Likewise, the nitrogen atom in the imine group (C= N) can act as a hydrogen bond acceptor, creating a hydrogen bond with hydrogen atoms in the MB dye59. Finally, the interaction of the sorbed component (PNP and MB) with the active sites of the sorbents (Ag°/glucose) might be responsible by hydrogen bonding, electrostatic contacts, the π–π interaction, and the hydrophobic interaction are the primary suggested interactions between PNP, MB, and Ag°/glucose, as seen in the FTIR scheme60.

Lab scale cost

From an economic standpoint, estimating the cost of producing Ag°/glucose is crucial. Consequently, the lab scale cost performance for synthesizing 100 milliliters of the current nanomaterial is summarized in Table 4. Herein, we must consider the following points:

-

The Ag°/glucose using in traces doses (20µL/mL).

-

The maximum adsorption capacity value was 2.5E + 3, and 10E + 3 mg/g for PNP and MB, respectively.

-

The possibility for reuse and regeneration and its positive impact on the coast will be examined in subsequent research.

We can summarize that the cost of remediating five liters containing 10 mg/L from PNP or MB by Ag°/glucose is almost equal to ~ 20 $. In comparison to the cost of poisonings, particularly those that occur in low- or middle-income countries or that affect children, this expense is negligible. According to one South African study, hospitalization for poisoning costs at least US$1.4 million annually in direct expenses61. Medical treatment accounted for nearly 9% of the nearly $400 million lifetime cost of poisonings in children under the age of fifteen. Including medical costs, lost earnings, and lost quality of life, this yields a conservative estimate of US$ 1780, on average, for each poisoning case62.

Comparative analysis with other greenly synthesized nanoparticles

Table 5. summarized a comparison between Ag°/glucose and other greenly silver nanoparticles according to their sources, characteristics, and catalytic efficiencies.

Novelty and future scope of the current study

The introduced qmax of the studied pollutants is extremely high and enables the current formula Ag°/glucose to be used on a large-scale wastewater remediation, even for different categories of pollutants. In the current study, the catalysis Ag°/glucose was used as an aqueous colloidal solution in a laboratory experiment to get a primary understanding of its efficiency as a catalyst. The priority in further studies is to immobilize the Ag°/glucose on an eco-friendly carrier and transfer it to a manufacturing scale.

Conclusions

This study introduces a promising green silver nanoparticle (Ag°/glucose) as a tool to remediate PNP or MB from synthetically contaminated water. From the presented data, it can be concluded that the features of Ag°/glucose are as follows: (1) simple and fast synthesis method. (2) distinctive characterizations (λ max at 430 nm, 21 to 31 nm diameter, and zeta potential equal to -16 mV). (3) time required for removing PNP and MB was observed as fifteen minutes when 20 µL/mL of Ag°/glucose was applied. (4) the pseudo-second order model describes adequately the kinetic data. (5) the Elovich model suggests that the initial rate constant was greater than the desorption constant for both PNP and MB. (6) Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models provides the good correlation for the PNP and MB equilibrium data, respectively. (7) the RL value was lower than one for both target pollutants. According to the research, Ag°/glucose has the potential to be an advantageous resource for treating wastewater, particularly when it comes to the organic materials pollutants.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are introduced and available within the manuscript.

References

Azeez, L., Lateef, A., Adebisi, S. A. & Oyedeji, A. O. Novel biosynthesized silver nanoparticles from cobweb as adsorbent for Rhodamine B: equilibrium isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Appl. Water Sci. 8, 1–12 (2018).

Khan, I. et al. Review on methylene blue: its properties, uses, toxicity and photodegradation. Water 14 (2), 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020242 (2022).

Albukhari, S. M., Ismail, M., Akhtar, K. & Danish, E. Y. Catalytic reduction of nitrophenols and dyes using silver nanoparticles@ cellulose polymer paper for the resolution of waste water treatment challenges. Colloids Surf., A. 577, 548–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.019.05.058 (2019).

Rajegaonkar, P. S. et al. Catalytic reduction of p-nitrophenol and methylene blue by microbiologically synthesized silver nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 93, 623–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.018.08.025 (2018).

Zhang, J., Chen, L. & Zhang, X. Removal of p-nitrophenol by nano zero valent iron-cobalt and activated persulfate supported onto activated carbon. Water 14:1387. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/w14091387(2022).

Mansee, A. H., Ebrahim, A. M. & Koreish, E. A. Simultaneous effective silver/Hordeum vulgare L. nanocomposite for treated wastewater contaminated with hexavalent chromium. J. Water Process. Eng. 65, 105805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.105805 (2024a).

Mansee, A. H., Ebrahim, A. M. & Koreish, E. A. Sustainable Indigenous bio-mixture for restoration the soil point source pollution with special reference to Chlorpyrifos. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196 (4), 363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-12494-5 (2024b).

Ganie, A. S., Bano, S., Khan, N., Sultana, S., Rehman, Z., Rahman, M. M., … Khan,M. Z. (2021). Nanoremediation technologies for sustainable remediation of contaminated environments: Recent advances and challenges. Chemosphere, 275, 130065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130065.

Samiey, B. & Farhadi, S. Kinetics and thermodynamics of adsorption of Fuchsin acid on nickel oxide nanoparticles. Acta Chim. Slov. 60 (4), 763–773 (2013).

Yang, K. & Xing, B. Adsorption of organic compounds by carbon nanomaterials in aqueous phase: Polanyi theory and its application. Chem. Rev. 110 (10), 5989–6008 (2010).

Satapanajaru, T., Chompuchan, C., Suntornchot, P. & Pengthamkeerati, P. Enhancing decolorization of reactive black 5 and reactive red 198 during nano zerovalent iron treatment. Desalination 266 (1–3), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.010.08.030 (2011).

Fouad, D. E. et al. Effects of sono-assisted modified precipitation on the crystallinity, size, morphology, and catalytic applications of hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles: A comparative study. Ultrason. Sonochem. 59, 104713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.019.104713 (2019).

Kalpana, D. et al. Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Torreya nucifera and their antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 12 (7), 1722–1732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.08.016 (2019).

Karki, H. P., Ojha, D. P., Joshi, M. K. & Kim, H. J. Effective reduction of p-nitrophenol by silver nanoparticle loaded on magnetic Fe3O4/ATO nano-composite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 435, 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.017.11.166 (2018).

Liao, G. et al. Ag-Based nanocomposites: synthesis and applications in catalysis. Nanoscale 11 (15), 7062–7096. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NR01408J (2019).

Demchenko, V., Riabov, S., Kobylinskyi, S., Goncharenko, L., Rybalchenko, N., Kruk,A., … Shut, M. (2020). Effect of the type of reducing agents of silver ions in interpolyelectrolyte-metal complexes on the structure, morphology and properties of silver-containing nanocomposites.Scientific Reports, 10(1), 7126.

Roto, R., Rasydta, H. P., Suratman, A. & Aprilita, N. H. Effect of reducing agents on physical and chemical properties of silver nanoparticles. Indonesian J. Chem. 18 (4), 614–620 (2018).

Haldar, A. G. M., Mahapatra, D. K., Dadure, K. M. & Chaudhary, R. G. Jordan journal of physics. Jordan J. Phys. 15 (1), 67–79 (2022).

Abada, E., Mashraqi, A., Modafer, Y., Al Abboud, M. A. & El-Shabasy, A. Review green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by using plant extracts and their antimicrobial activity. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 103877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2023.103877 (2023).

Mansee, A. H., Ebrahim, A. M. & Koreish, E. A. A promising sustainable green nanosilver formula for p-nitrophenol and methylene blue remediation from wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 14 (9), 205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-024-02258-4 (2024c).

Chand, K., Cao, D., Fouad, D. E., Shah, A. H., Dayo, A. Q., Zhu, K., … Dong, S. (2020).Green synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic application of silver nanoparticles synthesized by various plant extracts. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 13(11), 8248–8261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.020.01.009.

Darroudi, M., Ahmad, M. B., Abdullah, A. H., Ibrahim, N. A. & Shameli, K. Effect of accelerator in green synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11 (10), 3898–3905. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11103898 (2010).

Manimegalai, G., Shanthakumar, S. & Sharma, C. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis and application in mineralization of pesticides using membrane support. Int. Nano Lett. 4, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40089-014-0105-8 (2014).

Attatsi, I. K. & Nsiah, F. Application of silver nanoparticles toward Co (II) and Pb (II) ions contaminant removal in groundwater. Appl. Water Sci. 10, 152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-01240-0 (2020).

Devi, B. & Ahmaruzzaman, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Coccinia grandis fruit extract and its application toward the reduction of toxic nitro compounds. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 25, 475–841 (2018).

Dinh, V. P., Le, H. M., Nguyen, V. D., Dao, V. A., Hung, N. Q., Tuyen, L. A., … Tan,L. V. (2019). Insight into the adsorption mechanisms of methylene blue and chromium(III) from aqueous solution onto pomelo fruit peel. RSC advances, 9(44), 25847–25860.

Tang, X., Ran, G., Li, J., Zhang, Z. & Xiang, C. Extremely efficient and rapidly adsorb methylene blue using porous adsorbent prepared from waste paper: kinetics and equilibrium studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 402, 123579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.020.123579 (2021).

Guo, X. & Wang, J. A general kinetic model for adsorption: theoretical analysis and modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 288, 111100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.019.111100 (2019).

Hu, Q., Pang, S. & Wang, D. In-depth insights into mathematical characteristics, selection criteria and common mistakes of adsorption kinetic models: A critical review. Sep. Purif. Reviews. 51 (3), 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/15422119.2021.1922444 (2022).

Hu, Q. et al. Insights into mathematical characteristics of adsorption models and physical meaning of corresponding parameters. J. Mol. Liq. 254, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.018.01.073 (2018).

Simonin, J. P. On the comparison of pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws in the modeling of adsorption kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 300, 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.016.04.079 (2016).

Siddiqui, M. N. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and study of their antimicrobial properties. J. Polym. Environ. 26, 423–433 (2018).

Abed, M. S., Abed, A. S. & Othman, F. M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from natural compounds: glucose, Eugenol and thymol. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 60 (1), 95–111 (2019).

Chartarrayawadee, W. et al. Green synthesis and stabilization of silver nanoparticles using Lysimachia foenum-graecum hance extract and their antibacterial activity. Green. Process. Synthesis. 9 (1), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1515/gps-2020-0012 (2020).

Shimoga, G., Palem, R. R., Lee, S. H. & Kim, S. Y. Catalytic degradability of p-nitrophenol using ecofriendly silver nanoparticles. Metals 10 (12), 1661. https://doi.org/10.3390/met10121661 (2020).

Hossain, N. et al. Synthesis and characterization of rice husk Biochar via hydrothermal carbonization for wastewater treatment and biofuel production. Sci. Rep. 10, 18851 (2020).

Khan, I., Sadiq, M., Khan, I. & Saeed, K. Manganese dioxide nanoparticles/activated carbon composite as efficient UV and visible-light photocatalyst. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 5140–5154 (2019).

Singh, S. et al. Synthesis of Bi4Ti3O12-BaTiO3 nanocomposite, manifesting high dielectric and unique magnetic nature applicable in heterogeneous photocatalytic activity for degradation of Rhodamine B dye. Mater. Technol. 36 (8), 476–491 (2021).

Alabdullah, Z. T., Altameemi, I. A. & Sadda, A. M. A new comparison between Ag-Nano adsorbent and walnut shell adsorbent. Egypt. J. Chem. 64 (8), 4017–4026 (2021).

Hong, M., Zhang, L., Tan, Z. & Huang, Q. Effect mechanism of biochar’s zeta potential on farmland soil’s cadmium immobilization. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 26, 19738–19748 (2019).

Yusoff, N. F. M. et al. Investigation on the electrochemical performances of Mn2O3 as a potential anode for Na-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 9207 (2020).

Gul, S., Rehan, Z. A., Khan, S. A., Akhtar, K., Khan, M. A., Khan, M. I., … Khan,S. B. (2017). Antibacterial PES-CA-Ag2O nanocomposite supported Cu nanoparticles membrane toward ultrafiltration, BSA rejection and reduction of nitrophenol. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 230, 616–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.016.12.093.

Alencar, W. S. et al. Application of Mangifera indica (mango) seeds as a biosorbent for removal of victazol orange 3R dye from aqueous solution and study of the biosorption mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 209, 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.012.08.053 (2012).

Tural, B., Ertaş, E., Enez, B., Fincan, S. A. & Tural, S. Preparation and characterization of a novel magnetic biosorbent functionalized with biomass of Bacillus subtilis: kinetic and isotherm studies of biosorption processes in the removal of methylene blue. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5 (5), 4795–4802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.017.09.019 (2017).

Inyinbor, A. A., Adekola, F. A. & Olatunji, G. A. Liquid phase adsorptions of Rhodamine B dye onto Raw and Chitosan supported mesoporous adsorbents: isotherms and kinetics studies. Appl. Water Sci. 7, 2297–2307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-016-0405-4 (2017).

Bayuo, J., Pelig-Ba, K. B. & Abukari, M. A. Adsorptive removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution unto groundnut shell. Appl. Water Sci. 9 (4), 107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-0987-8 (2019).

Mansee, A. H., Abdelgawad, D. M., El-Gamal, E. H., Ebrahim, A. M. & Saleh, M. E. Influences of Mg-activation on sugarcane Bagasse Biochar characteristics and its PNP removing potentials from contaminated water. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 19153. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46463-8 (2023).

Adebayo, M. A. & Areo, F. I. Removal of phenol and 4-nitrophenol from wastewater using a composite prepared from clay and Cocos nucifera shell: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 3, 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resenv.021.100020 (2021).

Duman, O., Polat, T. G., Diker, C. Ö. & Tunç, S. Agar/κ-carrageenan composite hydrogel adsorbent for the removal of methylene blue from water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 160, 823–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.020.05.191 (2020).

Egbosiuba, T. C. et al. Ultrasonic enhanced adsorption of methylene blue onto the optimized surface area of activated carbon: adsorption isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 153, 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.019.10.016 (2020).

Hassan, W., Farooq, U., Ahmad, M., Athar, M. & Khan, M. A. Potential biosorbent, haloxylon recurvum plant stems, for the removal of methylene blue dye. Arab. J. Chem. 10, S1512–S1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.013.05.002 (2017).

Liu, L., Deng, G. & Shi, X. Adsorption characteristics and mechanism of p-nitrophenol by pine sawdust Biochar samples produced at different pyrolysis temperatures. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 5149 (2020).

Wasilewska, M., Marczewski, A. W., Deryło-Marczewska, A. & Sternik, D. Nitrophenols removal from aqueous solutions by activated carbon–temperature effect of adsorption kinetics and equilibrium. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9 (4), 105459 (2021).

Haydar, S., Ferro-Garcıa, M. A., Rivera-Utrilla, J. & Joly, J. P. Adsorption of p-nitrophenol on an activated carbon with different oxidations. Carbon 41 (3), 387–395 (2003).

Ewis, D. et al. Adsorption of 4-nitrophenol onto iron oxide bentonite nanocomposite: process optimization, kinetics, isotherms and mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Res. 16 (2), 23 (2022).

Bih, N. L. et al. Adsorption of phenol and methylene blue contaminants onto high-performance catalytic activated carbon from biomass residues. Heliyon, 11(1). (2025).

Akhi, A. A., Hasan, A., Saha, N., Howlader, S., Bhattacharjee, S., Dey, K., … Ganguli,S. (2024). Ophiorrhiza mungos-mediated silver nanoparticles as effective and reusable adsorbents for the removal of methylene blue from water. ACS omega, 9(4), 4324–4338.

Ren, Y. et al. Studies on kinetics, isotherms, thermodynamics and adsorption mechanism of methylene blue by N and S co-doped porous carbon spheres. Nanomaterials 11 (7), 1819 (2021).

Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Al-Absi, R. S. Mechanistic Understanding of the adsorption and thermodynamic aspects of cationic methylene blue dye onto cellulosic Olive stones biomass from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 15928 (2020).

Hamadeen, H. M., Elkhatib, E. A., Badawy, M. E. & Abdelgaleil, S. A. M. Green low cost nanomaterial produced from Moringa oleifera seed waste for enhanced removal of Chlorpyrifos from wastewater: mechanism and sorption studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105376 (2021).

Danseco, E. R., Miller, T. R. & Spicer, R. S. Incidence and costs of 1987–1994 childhood injuries: demographic breakdowns. Pediatrics 105 (2), e27–e27 (2000).

Durkin, M. S., Davidson, L. L., Kuhn, L., O’Connor, P. & Barlow, B. Low-income neighborhoods and the risk of severe pediatric injury: a small-area analysis in Northern Manhattan. Am. J. Public Health. 84 (4), 587–592 (1994).

Essa, W. K. Methylene blue removal by copper oxide nanoparticles obtained from green synthesis of Melia azedarach: kinetic and isotherm studies. Chemistry 6 (1), 249–263 (2024).

Gowda, S. A., Goveas, L. C. & Dakshayini, K. Adsorption of methylene blue by silver nanoparticles synthesized from Urena lobata leaf extract: kinetics and equilibrium analysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 288, 126431 (2022).

Abdelgawad, D. M., Ebrahim, A. M. & Mansee, A. H. Instant and efficient Greenly silver nanoparticles for remediating atrazine and methylene blue from contaminated water. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196 (12), 1–16 (2024).

Filsara, M., MokhtariHosseini, Z. B. & Mansoori-Rashvanloo, M. In situ green synthesis of iron nanoparticles on PVA nanofiber and its application in adsorptive removal methylene blue. Polym. Bull. 81 (18), 16827–16852 (2024).

dos S. Francisco, W., Rapachi, D., Igansi, A. V., Ruas, C. P., Pavan, F. A., Pinto,L. A., … Gelesky, M. A. (2024). Adsorption of silver nanoparticles by activated carbon from Eragrostis plana Nees: kinetics, equilibrium, and catalytic application in the degradation of 4-nitrophenol. Adsorption, 30(6), 925–933.

Khomeyrani, S. F. N., Ghalami-Choobar, B., Azqhandi, M. H. A. & Foroughi, M. An enhanced removal of para-nitrophenol (PNP) from water media using CaAl-layered double hydroxide-loaded magnetic g-CN nanocomposite. J. Water Process. Eng. 46, 102516 (2022).

Mishra, S., Yadav, S. S., Rawat, S., Singh, J. & Koduru, J. R. Corn husk derived magnetized activated carbon for the removal of phenol and para-nitrophenol from aqueous solution: interaction mechanism, insights on adsorbent characteristics, and isothermal, kinetic and thermodynamic properties. J. Environ. Manage. 246, 362–373 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Adsorption and co-adsorption mechanisms of p-nitrophenol and Pb (ii) on magnetic carbon aerogel in water. Environ. Science: Water Res. Technol. 8 (4), 820–835 (2022).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived and designed by A.H. M. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by A. M. E. and D. M. A. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A H. M., and all the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose, financially or otherwise.

Ethical approval

The ethical standards were followed precisely during this study. Additionally, at every stage of the research, the authors confirm the following: No person or animal was exposed to any component of the materials used in the research, so that any harm would occur. The authors did not use any live plants in this investigation. Components or materials were not used in the research in a manner or concentration that would cause direct or indirect harm to the individuals carrying out the research or those in charge of the various measurement processes. All the tools used in the research were applied in a scientific, healthy and accurate manner, which involved ensuring the safety of individuals and places in accordance with the governing local rules and laws.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mansee, A.H., Abdelgawad, D.M. & Ebrahim, A.M. Influence of glucose as a natural reductant on silver nanoparticles synthesis for decontamination of p-nitrophenol and methylene blue from wastewater. Sci Rep 15, 27085 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11974-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11974-z