Abstract

The firing stage is a critical phase in ceramic tile production, where the interplay of raw material composition and thermal treatment determine essential properties such as water absorption (WA) and bending strength (BS). This study employs advanced machine learning (ML) models to accurately predict these properties by capturing their complex nonlinear relationships. A robust dataset of 312 ceramic samples was analyzed, including variables such as particle size distribution, chemical and mineralogical composition, and firing temperatures ranging from 1000 to 1300 °C. Among the four ensemble ML models evaluated, CatBoost demonstrated the highest predictive performance. Model accuracy was assessed using multiple evaluation metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R²), root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). To enhance interpretability, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were used, revealing that clay mineral content and SiO₂ concentration were the most influential factors for WA, contributing approximately 40% and 30%, respectively. For BS, firing temperature (35%) and Al₂O₃ content (25%) were identified as the key predictors. Partial dependence plots further illustrated critical thresholds, such as a significant drop in WA above 62% SiO₂ and optimal BS values near 1200 °C, dindings that align with known ceramic processing principles while offering new, data-driven formulation insights. These results demonstrate the value of explainable artificial intelligence (AI) in enabling real-time process optimization, enhancing product consistency, and supporting energy-efficient ceramic manufacturing. Future work will focus on extendingthe dataset to include a wider variety of clay compositions and investigating hybrid modeling approaches for further improve predictive performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ceramic tile industry plays a pivotal role in modern construction, supplying durable, aesthetically versatile, and functionally diverse materials for architectural and building applications worldwide. Despite centuries of empirical optimization, the firing stage remains a crucial bottleneck in the production. Minor variations in raw material composition or thermal treatment can cause significant deviations in final product quality1. Accuratelly predicting key performance indicators such as water absorption (WA) and bending strength (BS) remains a persistent challenge due to complex, nonlinear relationships among numerous compositional, granulometric, and processing variables2. Traditional quality control approaches rely heavily on post-firing testing which often entails energy-intensive trial-and-error procedures, material waste, and inconsistent product performance3,4,5. These inefficiencies not only reduce manufacturing efficiency but also complicate compliance with standardized quality benchmarks. As a result, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into ceramic production is gaining momentum, offering promising avenues for real-time monitoring, improved energy efficiency, and enhanced product consistency6.

Previous studies7,8,9,10,11 have addressed aspects of this challenge using a range of analytical and computational techniques. Early studies12,13,14,15 investigated empirical correlations, such as the influence of clay plasticity on drying behavior – but were generally limited to narrow compositional tanges and lacked generalizability. Later, more sophisticated models including finite element simulations of heat transfer and kinetic analyses of phase transformations were introduced16,17. While these approaches advanced theoretical understanding, they often required highly specific input parameters that are impractical to obtain consistently in industrial settings. In recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool for material behavior prediction, with applications spanning from sintering dynamics to mechanical property estimation in non-oxide ceramics18. ML has also been used to optimize drying processes and predict the firing behavior of bricks using artificial neural networks (ANNs)19. However, few studies have applied ML to fully capture the complexity of the firing-stage for ceramic tiles produced from heterogeneous raw clays, a gap this study aims to address.

The current study introduces a comprehensive ML-based framework specifically designed for predictiong firing-stage outcomes in ceramic tile manufacturing. In contrast to earlier studies that employed single algorithms or small datasets, this research evaluates four ensemble learning models - CatBoost, XGBoost, GBM, and AdaBoost- across the broad, representative dataset. The dataset includes 19 input features encompassing chemical and mineralogical composition, particle size distribution, and firing temperature. This multi-model approach enhances prediction robustness and enables for a direct comparison of algorithm performance under identical conditions. Moreover, to improve transparency and interpretability, the study employs SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), a cutting-edge texhnique that elucidates the contribution of each input variable to the model`s predictions. For instance, the SHAP analysis reveals a strong nonlinear relationship between the SiO₂ content and WA, where a concentration exceeding 62% SiO₂ is associated with a notable improvement in vitrification, a trend that conventional linear models might overlook. By bridging the gap between fundamental materials science and industrial practice, the study contributes both practical tools for manufacturers and a scientific framework for understanding the firing process. The developed models are particularly significant for current industrial challenges, including the adoption of alternative aluminosilicate raw materials and the design of low-energy firing cycles, both of which are critical for advancing sustainability in ceramic production.

The novelty of this work lies in three core contributions: (1) the first comprehensive implementation of ensemble ML techniques for predicting firing-stage outcomes across diverse ceramic formulations; (2) the use of interpretable ML tools to extract actionable insights for process optimization; and (3) the establishment of performance benchmarks that can guide future research in traditional ceramic processing. Overall, the findings support the transition toward smarter, more adaptive manufacturing—an essential step toward achieving Industry 4.0 in the ceramics sector.

Experimental details: samples and methodology

Sample Preparation and characterization

The study examined 312 ceramic tile samples, selected to reflect industrial conditions and sourced from various geological locations to maximize compositional diversity. These samples primarily consisted of quartz and illite/kaolinite clay minerals, which are known to exhibit favorable ceramic-forming characteristics, as demonstrated in previous studies2,20,21. All samples underwent preparation steps to eliminate moisture and achieve homogeneous chemical, mineralogical, and granulometry composition. The raw materials were dried at about 105 °C for 24 h to remove free moisture, then pulverized using a planetary ball mill with zirconia grinding media. The resulting powder was sieved through a 0.5 mm mesh, with any retained particles reprocessed to guarantee complete size reduction and uniformity.

Chemical characterization was performed using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) spectroscopy (Spectro Xepos instrument), applying the fired pressed pellet method. Certified reference materials were used to calibrate the instrument and validate measurement accuracy. A critical aspect of the chemical analysis involved determining the loss on ignition (LOI) at 1000 °C, which accounts for the decomposition of clay minerals (dehydroxylation), combustion of organic matter, and decomposition of carbonates. This parameter proved essential for the accurate calculation of oxide concentrations in the final chemical analysis22.

Particle size distribution was quantified through a standardized combination of wet and dry sieving techniques23,24, providing detailed classification of sand (20–2000 μm), silt (2–20 μm), and clay (< 2 μm) fractions. Mineralogical composition was characterized using X-ray diffraction (Philips 1050 diffractometer) with the PDF-2 database for phase identification. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using Rietveld refinement, with results categorized into three primary groups: clay minerals (illite, kaolinite, smectite), quartz and feldspars, and carbonates. This comprehensive characterization approach ensured complete documentation of all factors significantly influencing firing behavior and the final product quality.

Dataset characteristics and feature analysis

The experimental dataset included 312 ceramic tile samples fired at various temperatures under the same firing regime, with comprehensive characterization of their composition and firing behavior. For the modelling, 80% of the data is used for training, and 20% is used for testing for both targets (WA and BS). Also, 5-fold cross-validation was adopted for the modelling. This strategy was selected to ensure both reliability and efficiency in model evaluation. The 80/20 split provides a robust test set for assessing performance on unseen data, while the 5-fold cross-validation within the training set offers a comprehensive estimate of model generalization. This combination mitigates overfitting risks and supports consistent parameter tuning across all models without incurring excessive computational costs. As detailed in Table 1, the particle size distribution showed sand content ranging from 3 to 63% (mean 20.50%), silt from 19 to 69% (mean 49.68%), and clay from 11 to 64% (mean 29.82%). Chemical analysis revealed SiO₂ as the dominant oxide that significantly varied in the composition of the tested raw clays (48.85–72.05%, mean 62.94%), followed by Al2O3 (18.94–29.18%, mean 22.39%), with Fe2O3 content between 1.03 and 3.33% (mean 1.81%). Minor oxides, including CaO (0.08–1.96%), MgO (0.57–2.14%), and K2O (0.57–4.24%), showed substantial variation across samples. Chemical components like SiO2 and Al2O3 exhibited approximately normal distributions, while minor oxides (e.g., SO3, MnO) showed right-skewed distributions due to their typically low concentrations. The chemical composition mainly showed satisfying chemical compositions expected to be applicable in the ceramic tile production25,26,27.

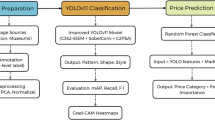

The mineralogical composition, determined through XRD analysis, featured high variability of the share of clay minerals from 22.35 to 83.00% (mean 48.38%) and quartz + feldspars between 20.50 and 68.20% (mean 47.59%). Carbonate content was low (0–2.50%, mean 0.15%), consistent with the raw materials’ kaolinitic and illitic nature. The flowchart of the analysis is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The database encompasses a broad and diverse range of raw clay compositions, supporting the model’s ability to generalize across a wider spectrum of ceramic systems, since it includes a wide span of chemical, mineralogical, and granulometric characteristics, such as SiO2 (48.8–72.0%), Al2O3 (18.9–29.2%), Fe2O3 (1.0–3.3%), LOI (2.7–16.2%), clay-sized fraction (11.0–64.0%), and clay minerals content (22.4–83.0%). While model generalization beyond the database to raw clays with entirely different input ranges may still be limited, this study demonstrates a clear methodology for selecting and applying machine learning models, as well as for analysing how raw clay properties influence ceramic tile quality. Given that all the selected machine learning models are tree-based and inherently robust to feature scale and variance, no feature scaling or normalization was applied. Furthermore, no prior feature selection techniques (e.g., PCA or filter-based methods) were implemented. Instead, the full set of 19 input variables was retained to allow the models’ internal learning mechanisms and subsequent SHAP-based interpretation to reveal the most influential predictors based on raw material composition and processing parameters. It is concluded that the database has the potential to represent various clays from around the world and predict their fired properties, provided they are processed in a similar manner to the samples studied here.

Firing temperatures spanned from 1000 °C to 1300 °C (mean 1190 °C), covering the wide typical industrial range for ceramic tile production28,29,30. Figure 2 presents the correlation heatmap of the relationships between the studied parameters. SiO2 showed a strong negative correlation with Al2O3 (r ≈ -0.8) and a positive correlation with quartz + feldspars content (r ≈ 0.7), confirming its association with non-clay mineral phases. The clay mineral content correlated positively with Al2O3 (r ≈ 0.6) and Fe2O3 (r ≈ 0.5), reflecting their presence in clay mineral structures31. The heatmap also identified partly unexpected relationships, such as the moderate positive correlation between LOI and Fe2O3 (r ≈ 0.5), proving that iron oxides, as fluxing agents, influence thermal decomposition behavior32.

The input distribution (Fig. 2) clustered most samples around 50% silt content, with sand and clay fractions displaying broader distributions. The firing temperature was evenly distributed across the experimental range, ensuring balanced representation in the modeling dataset.

Output parameters also demonstrated significant variation, with water absorption (WA) ranging from 0.10 to 12.14% (mean 5.09%) and bending strength (BS) in the range of 2.11–53.60 MPa (mean 28.96 MPa). Preliminary analysis suggested non-linear relationships between composition and performance metrics33, particularly for samples with extreme values in clay mineral content or firing temperature, motivating the use of machine learning approaches capable of capturing these complex interactions.

Theoretical framework and performance evaluation

Machine learning model architectures

CatBoost algorithm

CatBoost (Categorical Boosting) represents an advanced gradient boosting implementation designed to handle categorical features without extensive preprocessing34. The model employs ordered boosting, a permutation-driven approach that prevents target leakage, and innovative handling of categorical variables through target statistics35,36. During training, CatBoost builds symmetric decision trees (or oblivious trees) where each level uses the same splitting criterion, enhancing model robustness while reducing overfitting. The algorithm incorporates a novel gradient estimation scheme called Ordered Target Statistics, which processes examples in a random permutation order to calculate target statistics for each categorical feature value37. The CatBoost objective function combines the loss function L with regularization terms:

Where

T = number of leaves.

w = leaf weights.

\(\gamma ,\lambda =regularization~coefficients\)

Ordered boosting implements a modified gradient calculation:

Where gradients are computed using only the preceding samples in a random permutation.

XGBoost algorithm

The eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) implements a regularized gradient boosting framework that combines weak learners (decision trees) in an additive manner38. The algorithm distinguishes itself through several innovations: (1) a second-order Taylor approximation of the loss function that provides more accurate gradient estimates, (2) a novel tree pruning method based on the gain of splits rather than depth, and (3) efficient handling of sparse data patterns common in ceramic composition datasets. XGBoost’s objective function incorporates both prediction error minimization and model complexity control through terms for L1 (alpha) and L2 (lambda) regularization39. The grow policy parameter allows depth-wise or loss-guided tree development, while the colsample_bytree and subsample parameters enable stochastic feature and instance sampling, respectively. The regularized objective function at step t:

Where

The optimal weight \(w_{j}^{*}\) for leaf j:

Gradient boosting machine (GBM)

The Gradient Boosting Machine follows Friedman’s original gradient boosting framework, iteratively combining weak prediction models to create a strong ensemble40. Each new tree in GBM is fit to the negative gradient (pseudo-residuals) of the loss function from the current model ensemble. Key characteristics include: (1) adaptive boosting through shrinkage (learning rate parameter), which controls the contribution of each tree, (2) stochastic gradient boosting via subsampling of both training instances and features, and (3) flexible loss functions suitable for both regression (squared error) and probabilistic outputs. GBM employs a stagewise additive modeling approach, where each new tree corrects the errors of the existing ensemble41, making it particularly effective for capturing complex non-linear relationships between ceramic composition and the products` performance metrics. The interaction depth parameter controls whether the trees model simple main effects (depth = 1) or higher-order interactions between features.

At each iteration m, the algorithm fits a weak learner hm to pseudo-residuals:

The line search finds optimal \({\gamma _m}\):

The model update:

Where v is the learning rate.

AdaBoost algorithm

Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) operates by sequentially applying a base learner (typically decision stumps) to reweighted versions of the training data42. After each iteration, AdaBoost increases the weights of misclassified instances, forcing subsequent learners to focus on harder cases43. For regression tasks like ceramic property prediction, AdaBoost.R2 modifies this approach by weighting instances based on the magnitude of prediction errors. The algorithm combines weak learners through weighted majority voting, where each learner’s weight depends on accuracy. While less complex than gradient boosting variants, AdaBoost demonstrates effectiveness when dealing with certain types of ceramic data outliers and can serve as a valuable benchmark for more sophisticated ensemble methods. The n_estimators parameter controls the number of boosting iterations, while the learning rate adjusts the contribution of each weak learner.

For regression (AdaBooast. R2), the weighted median is computed:

Where \({\beta _m}=~{\epsilon _m}/\left( {1 - {\epsilon _m}} \right)\) and \({\epsilon _m}\) is the normalized error:

With Dm as the maximum error over all instances. The instance weights update:

Where Li is the loss for instance i.

Hyperparameter tuning strategy

To ensure optimal model performance, hyperparameter tuning was performed for all ensemble algorithms. For CatBoost, XGBoost, and GBM, a grid search method was applied across carefully selected parameter grids. The grids included parameters such as learning rate, maximum depth, number of estimators, subsample ratio, and column sampling rate, with ranges adapted to each algorithm’s recommended practices. For instance, CatBoost was tuned using learning rates ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 and tree depths between 4 and 10. However, for the AdaBoost model, being less computationally intensive, a random search approach was employed to efficiently explore a broader hyperparameter space. All hyperparameter tuning procedures were embedded within a 5-fold cross-validation loop on the training set to prevent overfitting and to validate model robustness. This approach ensured consistency in performance evaluation and allowed the selection of optimal configurations for each model prior to final testing.

Performance evaluation of the models

Various strategies are implemented to lower the risk of overfitting in machine learning models, a widely accepted guideline suggests using a dataset with at least ten times as many samples as input parameters44. The dataset used for modeling in this study has largely met this criterion, thereby avoiding the issue of overfitting. While the models developed in this study cannot be directly generalized to raw clays with input ranges beyond those represented in the current dataset, it nonetheless provides a clear framework for selecting and applying machine learning techniques. Moreover, the findings offer valuable insights into how the properties of raw clays influence the final quality of ceramic tiles, contributing meaningfully to methodology and practical understanding.

The performance of predictive models CatBoost, XGBoost, GBM, and AdaBoost was evaluated using four metrics: R2, MAPE, MAE, and RMSE. Each metric measures different aspects of accuracy and generalization. Higher R2 values indicate better model fit, while lower MAPE, MAE, and RMSE reflect improved prediction accuracy and reduced errors. The low level of errors proves the validity of the models.

Computational Efficiency Metrics, including training duration (in seconds) and inference rate (predictions per second), were additionally monitored to evaluate the practicality of deploying the models. While not direct measures of prediction accuracy, these metrics become critical when considering real-time process control applications in ceramic manufacturing environments. The trade-off between model complexity and computational requirements was evaluated through comparative analysis across the four algorithms employed.

Model interpretation techniques

SHAP (SHapley additive exPlanations)

SHAP values provide a unified measure of feature importance based on cooperative game theory45. SHAP values allocate the difference between the predicted outcome and the base value (average prediction) across the input parameters. This method ensures three key properties: (1) local accuracy, where the SHAP values sum up to match the prediction output), (2) missingness (features not present in the model get no attribution), and (3) consistency (if a model changes to rely more on a feature, its attribution cannot decrease). In ceramic property prediction, SHAP analysis reveals how specific compositional ranges (e.g., 60–65% SO2) influence WA and BS differently than other ranges.

Partial dependence plots (PDP)

PDPs visualize the marginal effect of one or two features on the predicted outcome after accounting for the average effect of all other features46. For continuous variables like firing temperature, PDPs show the expected change in WA or BS as temperature varies from 1000 °C to 1300 °C, holding other factors constant. These plots help identify critical thresholds (e.g., the temperature where BS improvement is achieved) and nonlinear relationships that inform ceramic processing conditions.

Permutation feature importance

This technique measures feature importance by calculating the increase in prediction error after randomly shuffling each feature’s values. Unlike SHAP values, which explain individual predictions, permutation importance provides a global view of which ceramic composition factors most affect model accuracy when their information is corrupted. The metric helps validate whether the models rely on scientifically plausible relationships between inputs and ceramic properties.

This robust framework enables comprehensive model performance evaluation while maintaining interpretability, a crucial factor for effective industrial deployment in ceramic manufacturing. By integrating diverse metrics with explanation techniques, this approach offers a multifaceted view of model behavior, spanning overall accuracy to intricate feature-outcome relationships. By implementing the best-behaved model in the future industrial practise, and also by employing a soft sensing technology, that would continually record and follow process parameters, the transition to industries 4.0 and 5.0 will be enabled.

Results and discussions

Comparison of the experimental and predicted values

The comparative analysis of the four ensemble models, CatBoost, XGBoost, GBM, and AdaBoost, revealed significant differences in their predictive capabilities for water absorption (WA) and bending strength (BS). As summarized in Table 2, CatBoost demonstrated superior performance, achieving an R2 of 0.9662 for WA and 0.9577 for BS, indicating that it explains over 95% of the variance in both target variables. The model’s low RMSE values (0.4549 for WA and 1.8661 for BS) further confirmed its precision, with minimal deviation between predicted and experimental values. XGBoost closely followed, with R2 values of 0.9613 (WA) and 0.9576 (BS), suggesting that its tree-pruning and regularization techniques also effectively captured the complex relationships in the dataset47. While slightly less accurate (R2 ~ 0.95), the GBM model still provided robust predictions, reinforcing the utility of gradient boosting for the fired ceramic properties modeling. In contrast, AdaBoost exhibited substantially higher errors, particularly for BS (RMSE: 3.4546), likely due to its reliance on weak learners and limited capacity to model high-order feature interactions. Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 illustrate the highlighted findings. The scatter plots for CatBoost (Figs. 3 and 7) display a near-perfect alignment between predicted and experimental values, with data points tightly clustered along the unity line. This consistency held across the full range of WA (0.10–12.14%) nd BS (2.11–53.60 MPa), demonstrating the model’s reliability even for extreme compositions. XGBoost (Figs. 4 and 8) displayed comparable patterns, though with slightly greater variability at higher WA values (> 8%),potentially due to its approach to sparse data. GBM (Figs. 5 and 9) tended to underestimate BS in the mid-range (20–35 MPa), indicating potential improvements through hyperparameter optimization. On the other hand, AdaBoost (Figs. 6 and 10) consistently overpredicted BS for high-strength samples (> 40 MPa), exposing its limitations in capturing nonlinear sintering effects. These findings highlight the critical role of model selection, with CatBoost and XGBoost standing out as top contenders for the future industrial use cases demanding precise accuracy.

Partial dependence plot for the best model for BS prediction

The partial dependence plot (PDP) for CatBoost (Fig. 11) provides critical insights into the relationship between firing temperature and BS, independent of other variables. The plot reveals a nonlinear, sigmoidal trend: BS increases gradually from 1000 to 1150 °C, then rises sharply until 1200 °C, after which the improvements diminish. This behavior aligns with known ceramic sintering dynamics, where temperatures below 1150 °C are often insufficient for complete densification, while those above 1200 °C yield diminishing returns due to overfiring risks (e.g., excessive glass phase formation)30,48. The inflection point at 1180 °C is particularly noteworthy, as it marks an optimal thermal threshold for maximizing strength without incurring excess energy use.

Furthermore, the PDP highlights the interplay between the firing temperature and chemical composition. For instance, samples with high Al₂O₃ (> 24%) showed steeper BS gains at lower temperatures (1100–1175 °C), likely due to accelerated mullite crystallization, which begins at 1000 °C (primary mullite), but its quantity further increases with temperature49. Conversely, SiO2-rich formulations (> 65%) equired higher temperatures (1225–1300 °C) to achieve comparable strength, reflecting their reliance on glass-phase sintering. These findings provide a basis for manufacturers to tailor firing schedules to raw material compositions, thereby reducing energy demand while ensuring consistent product quality.

Sensitivity analysis for the best model – CatBoost

The sensitivity analysis provided profound insights into how compositional and processing variables influence the key ceramic properties of water absorption and bending strength. Figures 12 and 13 present the sensitivity analysis for WA using CatBoost and BS using CatBoost, respectively.

For the water absorption parameter, clay mineral content proved the most influential factor, contributing approximately 40% to the model’s predictive accuracy. This dominant role reflects the fundamental importance of clay-sized particles and mineralogy in determining the pore structure evolution during firing50. The analysis identified a pronounced nonlinear pattern, showing that samples with more than 50% cay particle content experienced a sharp exponential decline in water absorption. This highlights how fine clay particles efficiently occupy interparticle spaces during the sintering process.

Silicon dioxide concentration showed the second strongest influence, contributing to about 30% of the water absorption predictions. The sensitivity analysis uncovered a critical compositional threshold at 62% SiO2, beyond which water absorption values dropped sharply. This phenomenon correlates well with ceramic engineering principles, where sufficient silica content promotes extensive glass phase formation, effectively sealing surface porosity. Conversely, an excessive proportion of SiO2 indicates a scarcity of clay minerals and the use of unsuitable clays for ceramic tile production. The remaining 30% of predictive influence was distributed among various minor components, with iron oxide and alkali metals showing modest but measurable effects through their fluxing actions during firing51.

For BS, the sensitivity analysis painted a different but equally informative picture. Firing temperature dominated the predictions with a 35% contribution, displaying a characteristic sigmoidal relationship where strength gains accelerated between 1150 and 1200 °C before plateauing at higher temperatures, which was seen previously. Al2O3 content followed closely in importance at 25%, with the analysis revealing two optimal concentration ranges near 20% and 25% that correspond to different stages of mullite crystallization49. The influence of magnesium oxide, accounting for about 5% o the predictions, may be attributed to its role in forming high-temperature spinel phases that reinforce the ceramic matrix or its act as a flux.

Taylor diagram for standard deviation and correlation

The Taylor diagrams (Figs. 14 and 15) provide a holistic assessment of model performance by comparing simulated and observed variability52. For WA (Fig. 14), CatBoost and XGBoost nearly overlapped at the ideal point (correlation: 0.98–0.99; standard deviation ratio: 0.97–1.02), confirming their ability to replicate both the magnitude and distribution of experimental data. GBM showed a slight overestimation of variability (ratio: 1.08), while AdaBoost’s low correlation (0.85) and inflated standard deviation (1.35) revealed systematic prediction errors.

For BS (Fig. 15), the results were even more pronounced. CatBoost achieved near-perfect alignment (correlation: 0.99; ratio: 1.01), whereas AdaBoost’s poor fit (correlation: 0.82; ratio: 1.42) underscored its unsuitability for strength prediction.

SHAP feature importance

The SHAP analyses (Figs. 16, 17, 18 and 19) serve as a powerful interpretability tool, translating the CatBoost model’s complex, high-dimensional outputs into chemically and technologically meaningful insights. By attributing predictive importance to individual features, these analyses provide a transparent understanding of how input variables influence key ceramic properties, thereby fostering trust in machine learning predictions while deepening our comprehension of composition–property relationships in ceramic materials. Figure 16 illustrates the dominant influence of firing temperature on bending strength. The SHAP values increase linearly up to 1200 °C, beyond which they plateau, a trend that closely aligns with the partial dependence plot and confirms the existence of an optimal thermal processing window. This behavior supports the empirical understanding that thermal activation up to a certain threshold enhances densification and phase development, beyond which further heating yields diminishing returns. The observed plateau thus signifies not only the thermodynamic limit of strength gains but also points to a practical energy-efficiency boundary in industrial processing30.

In Fig. 17, the SHAP value distribution for aluminium oxide reveals a more intricated response, with prominent peaks at 20 and 25% concentrations. These concentrations correspond to critical transitions in the firing process: the onset of kaolinite decomposition around 20%, and the formation of needle-like mullite crystals near 25%, which are well-documented contributions to mechanical reinforcement in ceramics2,53. This dual-peak behavior substantiates the relevance of Al2O3 as a structural optimizer and quantitatively supports its role as a key lever in tuning mechanical performance21, validating long-standing ceramic knowledge with data-driven evidence.

Turning to water absorption, Fig. 18 underscores the critical role of silicon dioxide content. Below 60%, SHAP values remain near-neutral, but a sharp negative trend emerges above 62%, indicating that higher SiO2 concentrations significantly reduce water absorption. This threshold effect is associated with enhanced glass-phase formation and pore closure during sintering, both of which are critical for producing low-porosity ceramic bodies54. Notably, this finding emphasizes the delicate balance required: while adequate silica promotes vitrification, excess levels can dilute structural components or introduce defects if not properly controlled-offering a refined target for silica optimization. Figure 19 complements this by revealing the significant contribution of clay minerals, particularly the dominance of illite-rich raw materials21. Samples with clay mineral contents exceeding 55%, partcularly those with a high illite fraction, show strong negative SHAP values for water absorption, indicating a superior ability to limit porosity. This effect may be attributed to illite`s moderate plasticity and its high fluxing behavior2. However, it is important to acknowledge that the model`s conclusions are shaped by the composition of the underlying database, which dominantly features illitic clays. Future expansions of the dataset to include more samples containing more kaolinite, smectite, or mixed-layer clays would help test the generalizability of these trends.

Beyond individual variable effects, SHAP interaction values offer deeper into synergistic or antagonistic relationships between features. For example, Fig. 16 reveals that the positive impact of high firing temperatures on strength is enhanced in samples with elevated Al2O3 content55, suggesting that thermal and compositional optimization must be co-considered for maximum performance. Similarly, in Fig. 18, the sharp SiO2 threshold effect becomes more pronounced in raw clays with finer particle size distributions, indicating that granulometry modulates vitrification efficiency and pore sealing. The strength-enhancing effect of firing temperature is significantly amplified when Al₂O₃ content exceeds 23%, suggesting that thermal activation and mullite crystallization work in tandem to boost mechanical performance. Such multidimensional interactions are challenging to detect through conventional experimental approaches, but emerge clearly through SHAP visualizations. For instance, the data support prioritizing silica control for floor tile applications where water resistance is paramount, while simultaneously guiding structural ceramic producers to focus on Al2O3 adjustments within the identified optimal ranges.

These findings have significant implications for ceramic process engineering. The ability to identify precise compositional thresholds and synergistic effects enables the development of more targeted, high-performance formulations. For instance, producers of moisture-resistant floor tiles can focus on fine-tuning silica levels while maintaining optimal granulometry, whereas refractory ceramic applications may benefit more from Al2O3 optimization within the identified effective ranges. The interpretability afforded by SHAP thus not only validates the model but also enhances formulation strategies in ways that align with both scientific principles and manufacturing constraints.

In conclusion, the SHAP analysis achieves two critical outcomes. First, it confirms that the machine learning model’s predictions are grounded in established ceramic science, reinforcing confidence in its applicability. Second, it expands the domain of ceramic knowledge by uncovering nonlinearities and interaction effects that are difficult, if not impossible, to isolate through traditional experimentation. This integrative approach bridges the gap between advanced data analytics and practical ceramic engineering, paving the way for the widespread adoption of machine learning in industrial quality control, material selection, and process optimization. Crucially, the ability to trace model decisions back to tangible material characteristics marks a substantial advancement toward explainable, data-driven ceramic design.

Conclusions

The firing stage, a pivotal phase in ceramic tile production, influences key metrics like water absorption and bending strength through the complex interplay of raw material composition and thermal treatment. To tackle challenges in predicting these properties, advanced machine learning (ML) models, CatBoost, XGBoost, GBM, and AdaBoost, were developed using a dataset of 312 samples covering particle size distribution, chemical composition, mineralogy, and firing temperatures (1000–1300 °C). CatBoost showed superior accuracy, while SHAP analysis highlighted the significant roles of clay mineral content, SiO2 concentration, firing temperature, and Al2O3 levels. Partial dependence plots pinpointed critical thresholds, such as reduced WA at 60–62% SiO2 and optimal BS at around 1200 °C. These findings not only deepen the understanding of performance factors but also support manufacturers in optimizing processes for consistent quality and energy efficiency. Integrating the ML models into industrial practices could revolutionize ceramic production while paving the way for future advancements through expanded datasets and hybrid models.

Although the current dataset spans a wide range of illitic and kaolinitic raw clays, it does not fully encompass all possible regional clay chemistries. To extend model applicability, future research should focus on expanding the dataset to include diverse clay types from other geographic regions, such as smectite- or chlorite-rich systems. Additionally, the current modeling framework can support transfer learning or fine-tuning approaches, where new data are used to adapt pre-trained models without requiring complete retraining. This adaptability, combined with SHAP-driven interpretability, can facilitate localized process optimization, enabling manufacturers in different regions to adopt similar data-driven strategies even with varying raw material sources. SHAP analysis validates the machine learning model’s consistency with ceramic science principles while deepening our understanding of composition-property relationships. It highlights nonlinear effects and interactions beyond the scope of lab experiments, establishing a solid foundation for data-driven ceramic design. This approach enhances interpretability, connecting advanced machine learning techniques with practical ceramic engineering and enabling progress in industrial quality control and process optimization.

Key actionable insights for ceramic tile manufacturers and practitioners:

-

Optimize firing temperatures around 1180–1200 °C to maximize strength without overfiring or wasting energy.

-

Target SiO₂ contents above 62% and clay mineral contents above 50% to significantly reduce water absorption through enhanced vitrification.

-

Use Al2O3 levels around 20–25% to promote mullite crystallization and boost mechanical performance.

-

Consider SHAP-based interpretation in digital quality control systems to monitor feature contributions in real time.

-

Apply the developed CatBoost/XGBoost models for formulation screening prior to full-scale production, minimizing trial-and-error and material waste.

-

Expand local datasets and retrain the model periodically to adapt predictions to regional clay variability.

-

Combine the modeling framework with soft sensing tools to support real-time feedback in Industry 4.0 environments.

Future works:

Several promising strategies can help broaden the applicability of the developed models. Transfer learning may allow the adaptation of pretrained models to new datasets with limited regional samples, improving efficiency in data-scarce scenarios. Data augmentation, including synthetically generated compositions based on domain constraints, can enhance model robustness and balance underrepresented classes. Additionally, physics-informed machine learning (PIML) offers an emerging framework to embed ceramic processing laws (e.g., sintering kinetics or phase transformation rules) directly into model training. Integrating these techniques will strengthen both the accuracy and reliability of AI tools for global ceramic tile production systems.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lakhdar, Y., Tuck, C., Binner, J., Terry, A. & Goodridge, R. Additive manufacturing of advanced ceramic materials. Prog Mater. Sci. 116, 100736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100736 (2021).

Vasić, M. V., Radovanović, L., Pezo, L. & Radojević, Z. Raw kaolinitic–illitic clays as high-mechanical-performance hydraulically pressed refractories. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 148, 1783–1803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-022-11848-w (2023).

Coskun, H., Yi̇ği̇t, T. & Üncü, İ. S. Integration of digital quality control for intelligent manufacturing of industrial ceramic tiles. Ceram. Int. 48, 34210–34233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.05.224 (2022).

Jovic, F., Jovic, A. & Krmpotic, D. Quality control engineering in automated ceramic tile production using a signal information content approach. Adv. Eng. Inform. 27, 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2012.11.007 (2013).

Murugesan, R., Ragul, T., Edison, J. & Vinoth, T. Automated quality monitoring system for ceramic tiles. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 912, 032027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/912/3/032027 (2020).

Gallareta, J. G., González-Menorca, C., Muñoz, P. & Vasic, M. V. Advancements in soft sensor technologies for quality control in process manufacturing: a review. IEEE Sens. J. 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2025.3549596 (2025).

Yang, A., Romanyk, D. & Hogan, J. D. High-velocity impact study of an advanced ceramic using finite element model coupling with a machine learning approach. Ceram. Int. 49, 10481–10498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.11.234 (2023).

Chen, J., Cheng, Y. & Guo, Q. Evaluation method and the influence of visual comfort of ceramic tiles in indoor Environment—a study based on the Delphi and AHP. Buildings 14, 2829. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092829 (2024).

Jayaweera, J. M. N., Narayana, M. & Adikary, S. U. Numerical Modeling of Drying Behavior of Ceramic Tiles with High Silica Content of Kaolin, in: 2023 Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference (MERCon) 592–597 (IEEE, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/MERCon60487.2023.10355459.

Mandal, A. & Rajput, S. P. S. Computational optimization of ceramic Waste-Based concrete mixtures: a comprehensive analysis of machine learning techniques. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10233-8 (2025).

Tiscar, J. M., Escrig, A., Mallol, G., Boix, J. & Gilabert, F. A. DEM-based modelling framework for spray-dried powders in ceramic tiles industry. Part I: calibration procedure. Powder Technol. 356, 818–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2019.08.053 (2019).

Andrade, F. A., Al-Qureshi, H. A. & Hotza, D. Measuring the plasticity of clays: a review. Appl. Clay Sci. 51, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2010.10.028 (2011).

Zaccaron, A., de Souza Nandi, V., Dal Bó, M., Arcaro, S. & Bernardin, A. M. The behavior of different clays subjected to a fast-drying cycle for traditional ceramic manufacturing. J. King Saud Univ. - Eng. Sci. 36, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksues.2022.05.003 (2024).

Nandi, V. S. et al. Plastic behaviour of clay materials for the manufacture of fast-drying red ceramics. Clay Min. 58, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1180/clm.2023.9 (2023).

de Andrade, F. A., Al-Qureshi, H. A. & Hotza, D. Measuring and modeling the plasticity of clays. Mater. Res. 13, 395–399. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-14392010000300019 (2010).

Raether, F., Klimera, A. & Baber, J. In situ measurement and simulation of temperature and stress gradients during sintering of large ceramic components. Ceram. Int. 34, 385–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2006.10.025 (2008).

Amorós, J. L., Blasco, E., Moreno, A. & Feliu, C. Kinetics of the transformations occurring during the firing process of an industrial spray-dried porcelain stoneware body. Ceram. Int. 48, 17611–17620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.03.031 (2022).

Song, W. et al. Data-driven prediction of sintering and deformation behavior of ZrO2 ceramics. Ceram. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.03.411 (2025).

Saif, S., Mubin, S., Abbass, W., Aslam, F. & Alyousef, R. Utilizing machine learning to integrate silica-based production waste material in ceramic tiles manufacturing: progressing toward sustainable solutions. Ceram. Int. 50, 18880–18906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.02.377 (2024).

Mijatović, N., Vasić, M., Miličić, L., Radomirović, M. & Radojević, Z. Fired pressed pellet as a sample Preparation technique of choice for an energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence analysis of Raw clays. Talanta 252, 123844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2022.123844 (2023).

Vasić, M. V. et al. What is the most relevant method for water absorption determination in ceramic tiles produced by illitic-kaolinitic clays? The mystery behind the gresification diagram. Boletín De La. Sociedad Española De Cerámica Y Vidrio. 61, 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2020.11.006 (2022).

Cordoba, G., Rossetti, A., Falcone, D. & Irassar, E. F. Sulfate and Alkali-Silica Performance of Blended Cements Containing Illitic Calcined Clays 117–123 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1207-9_19.

SRPS U.B1.018. Testing of soils—determination of particle size distribution (2005).

Vasić, M. V., Radomirović, M., Velasco, P. M. & Mijatović, N. Geochemical profiles of deep sediment layers from the Kolubara district (Western Serbia): Contamination Status and Associated Risks of Heavy Metals. Agronomy 14, 3009. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14123009 (2024).

Strazzera, B., Dondi, M. & Marsigli, M. Composition and ceramic properties of tertiary clays from Southern Sardinia (Italy). Appl. Clay Sci. 12, 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-1317(97)00010-0 (1997).

Galos, K. Composition and ceramic properties of ball clays for porcelain stoneware tiles manufacture in Poland. Appl. Clay Sci. 51, 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2010.11.004 (2011).

Rodrigues, L. & De Holanda, J. Valorization of municipal waterworks sludge to produce ceramic floor tiles. Recycling 3, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling3010010 (2018).

Sremac, S., Backalic, Z., Petrovic, V., Jovanovic, D. & Vasic, M. Shortening of fast firing in the ceramic tile production by inorganic additives - an upscale to the industry. Sci. Sinter. 4, 4. https://doi.org/10.2298/SOS231213004S (2024).

Castellano, J., Sanz, V., Cañas, E. & Sánchez, E. Effect of firing temperature on humidity self-regulation functionality in a ceramic tile composition. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 42, 6236–6243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2022.05.058 (2022).

Martínez-Martínez, S., Pérez-Villarejo, L., Garzón, E. & Sánchez-Soto, P. J. Influence of firing temperature on the ceramic properties of illite-chlorite-calcitic clays. Ceram. Int. 49, 24541–24557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.11.077 (2023).

Murray, H. H. Chap. 2 Structure and Composition of the Clay Minerals and their Physical and Chemical Properties 7–31 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-4352(06)02002-2.

Li, Y., Zhao, L., Wang, Y. & Cang, D. Effects of Fe2O3 on the properties of ceramics from steel slag. Int. J. Minerals Metall. Mater. 25, 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-018-1586-7 (2018).

Scott, D. J., Coveney, P. V., Kilner, J. A., Rossiny, J. C. H. & Alford, N. M. N. Prediction of the functional properties of ceramic materials from composition using artificial neural networks. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 27, 4425–4435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2007.02.212 (2007).

Sobolewski, R. A., Tchakorom, M. & Couturier, R. Gradient boosting-based approach for short- and medium-term wind turbine output power prediction. Renew. Energy. 203, 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.12.040 (2023).

Malashin, I., Tynchenko, V., Gantimurov, A., Nelyub, V. & Borodulin, A. Boosting-Based machine learning applications in polymer science: a review. Polym. (Basel) 17 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17040499. (2025).

Nguyen, N. & Ngo, D. Comparative analysis of boosting algorithms for predicting personal default. Cogent Econ. Finance. 13, 523. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2025.2465971 (2025).

Chen, Y., Chen, B. & Shayilan, A. Combining categorical boosting and Shapley additive explanations for Building an interpretable ensemble classifier for identifying mineralization-related geochemical anomalies. Ore Geol. Rev. 173, 106263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2024.106263 (2024).

Chakraborty, A. & Tsokos, C. P. An AI-driven predictive model for pancreatic Cancer patients using extreme gradient boosting. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 22, 262–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44199-023-00063-7 (2023).

Mauer, P. & Paszkiel, S. Tabular data models for predicting Art auction results. Appl. Sci. 14, 11006. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142311006 (2024).

AlShourbaji, I. et al. An efficient churn prediction model using gradient boosting machine and metaheuristic optimization. Sci. Rep. 13, 14441. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41093-6 (2023).

Khan, A. A., Chaudhari, O. & Chandra, R. A review of ensemble learning and data augmentation models for class imbalanced problems: combination, implementation and evaluation. Expert Syst. Appl. 244, 122778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122778 (2024).

de Giorgio, A., Cola, G. & Wang, L. Systematic review of class imbalance problems in manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 71, 620–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2023.10.014 (2023).

Hussain, S. S. & Zaidi, S. S. H. AdaBoost ensemble approach with weak classifiers for gear fault diagnosis and prognosis in DC motors. Appl. Sci. 14, 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14073105 (2024).

Alwosheel, A., van Cranenburgh, S. & Chorus, C. G. Is your dataset big enough? Sample size requirements when using artificial neural networks for discrete choice analysis. J. Choice Modelling. 28, 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocm.2018.07.002 (2018).

Zong, X. et al. Advanced ceramics with integrated structures and functions: machine learning prediction and experimental verification. Ceram. Int. 50, 24126–24138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.04.144 (2024).

Molnar, C. et al. Relating the Partial Dependence Plot and Permutation Feature Importance to the Data Generating Process 456–479 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44064-9_24.

Xia, Y., Jiang, S., Meng, L. & Ju, X. XGBoost-B-GHM: an ensemble model with feature selection and GHM loss function optimization for credit scoring. Systems 12, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12070254 (2024).

Contartesi, F., Melchiades, F. G. & Boschi, A. O. Anticipated overfiring in porcelain tiles: effects of the firing cycle and green bulk density. Boletín De La. Sociedad Española De Cerámica Y Vidrio. 58, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2018.07.001 (2019).

Chargui, F. et al. Mullite fabrication from natural Kaolin and aluminium slag. Boletín De La. Sociedad Española De Cerámica Y Vidrio. 57, 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2018.01.001 (2018).

El-Fadaly, E. A., Askar, A. S., Aly, M. H. & Ibrahim, D. M. Rheological, physico-mechanical and microstructural properties of porous mullite ceramic based on environmental wastes. Boletín De La. Sociedad Española De Cerámica Y Vidrio. 61, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2020.08.002 (2022).

Goltsman, B. M. & Yatsenko, E. A. Modern fluxing materials and analysis of their impact on silicate structures: a review. Open. Ceram. 17, 100540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceram.2024.100540 (2024).

Ghorbani, M. A. et al. The Taylor diagram with distance: a new way to compare the performance of models. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civil Eng. 49, 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01477-8 (2025).

Zhang, Q. et al. Preparation of porous mullite ceramics consisting of needle-like mullite whiskers. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 120, 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/17436753.2021.1924569 (2021).

Purnawan, I., Prabowo, A. T. & Rudiatin, S. E. The effect of clay and SiO2 composition on the physical properties of wall tile ceramic body. In AIP Conference Proceedings 070003 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0181074.

Varışli, S. Ö., Taşkıran, F., Öztürk, B. & Çiçek, B. Effect of SiO2/Al2O3 ratio on the whiteness of ceramic tile engobes with low Zircon content. Cerâmica 69, 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1590/0366-69132023693913465 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge help and support from the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract number 451-03-136/2025-03/ 200012). The authors are grateful to University North, Croatia, for financial support within the “Circular Economy in the Construction Industry” project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MVV - Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Review and editing, POA - Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, writing original draft, Review and editing, OGF- Methodology, investigation, Review and editing , IB - Methodology, investigation, Review and editing, ING - Methodology, investigation, Review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vasić, M.V., Awoyera, P.O., Fadugba, O.G. et al. Advanced machine learning models for the prediction of ceramic tiles’ properties during the firing stage. Sci Rep 15, 31397 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12011-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12011-9