Abstract

The rapid proliferation of cloud computing enables users to access computing resources and storage space over the internet, but it also presents challenges in terms of security and privacy. Ensuring the security and availability of data has become a focal point of current research when utilizing cloud computing for resource sharing, data storage, and querying. Public key encryption with equality test (PKEET) can perform an equality test on ciphertexts without decrypting them, even when those ciphertexts are encrypted under different public keys. That offers a practical approach to dividing up or searching for encrypted information directly. In order to deal with the threat raised by the rapid development of quantum computing, researchers have proposed post-quantum cryptography to guarantee the security of cloud services. However, it is challenging to implement these techniques efficiently. In this paper, a compact PKEET scheme is pro-posed. The new scheme does not encrypt the plaintext’s hash value immediately but embeds it into the test trapdoor. We also demon-strated that our new construction is one-way secure under the quantum security model. With those efforts, our scheme can withstand the chosen ciphertext attacks as long as the learning with errors (LWE) assumption holds. Furthermore, we evaluated the new scheme’s performance and found that it only costs approximately half the storage space compared with previous schemes. There is an almost half reduction in the computing cost throughout the encryption and decryption stages. In a nutshell, the new PKEET scheme is less costly, more compact, and applicable to cloud computing scenarios in a post-quantum environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Because of the rapid growth of information technology and mobile Internet technology, global data is rising explosively. That brings up the issue of how to store and process all of the newly incoming data on digital devices efficiently. Cloud computing, as a new type of computing, offers a wide range of potential applications. Specifically, it can provide convenient data storage, remote access, and resource sharing. Cloud computing offers dependable, high quality cloud services to a huge number of users. Users can store large amounts of data on cloud servers and obtain outsourced computing from them, relieving the traffic pressure on local servers. However, in order to ensure cloud data privacy, users prefer to keep their sensitive information in an encrypted manner. As cloud servers are unable to do computations on encrypted data, it becomes a significant difficulty for cloud servers to manage them in this case.

Downloading the encrypted data and decrypting it before searching is an easy way to address the aforementioned issue. But this idea is so inefficient and expensive that it is impractical for large datasets. Therefore, researchers aim to find ways to execute calculations directly without decryption. Fortunately, technologies such as Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE)1, Searchable Encryption (SE)2, and Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) offer effective solutions. Searchable encryption is proposed in 2004. In a SE scheme, users create trapdoors from unencrypted keywords and upload them to the cloud together with ciphertext. With two correlative trapdoors, one can determine whether keywords k and k ′ are equal. The SE technique allows the cloud server to categorize ciphertexts using plaintext keywords, but all the ciphertexts must be encrypted using the same key.

Searchable encryption schemes are no longer practical in some situations, such as medical systems and spam filtering. They are required to classify encrypted information with different keys. In CT-RSA 2010, Yang et al.3 proposed the PKEET for the first time. It enables the user to detect whether two ciphertexts are from the same plaintext, and the two ciphertexts can be encrypted by different keys. That makes it very useful in some scenarios, e.g., in cloud-assisted vehicular networks.

Figure 1 shows a typical application scenario of PKEET in the cloud environment for the Internet of Vehicles system. In this system, when a cloud user (vehicle terminal) encounters special road conditions such as road construction, traffic congestion, or emergencies, they can query other users with similar experiences to share experiences and obtain useful information. PKEET can ensure that these users obtain the required information without sacrificing privacy, greatly enhancing the information exchange and mutual assistance ability between users. Furthermore, vehicles can not only share data with roadside devices, but also upload data to the traffic control center’s servers for backup4. Users can retrieve the relevant data from the cloud server as proof in the event of a traffic accident5.

In addition to efficiency, security is another important aspect of cloud computing. So far, Shor6 has claimed that a huge quantum computer can successfully resolve most of the traditional hard problems, including the discrete logarithm and the large integer factorization problems. Consequently, in the upcoming era of quantum computing, any PKEET schemes founded on these conventional assumptions would be considered unsafe. Because there are no quantum algorithms that can successfully solve the lattice problems effectively yet, it is generally believed that the cryptographic schemes based on lattice assumptions are safe in quantum environment. To address the threats brought by quantum technology, we try to construct the PKEET scheme on a lattice problem. This initiative aims to bolster the security of cloud computing infrastructures in anticipation of the post-quantum era.

Related works

Public key encryption with keyword search

In 2004, Boneh et al.2first introduced the concept of Public Key Encryption with Keyword Search (PEKS) and constructed the first scheme. However, in 2006, Byun et al.7 pointed out that the scheme had security issues and could suffer from keyword guessing attacks. In 2009, Tang et al.8 proposed a scheme with registered keyword search, in which the data owner registers a keyword with the data receiver before generating a ciphertext label for the keyword. And the authors prove that the security of the scheme is not affected by keyword guessing attacks. However, because the scheme involves a secure channel in the design of the keyword registration algorithm, its practical value is not high. In 2012, Xu et al.9 proposed a scheme with fuzzy keyword search, which divides ciphertext retrieval into two stages. In the first stage, fuzzy retrieval is carried out on the cloud server. Then, the data receiver performs a precise local search to obtain the required file. Since the attacker cannot obtain the exact search trapdoor, the scheme can effectively resist the keyword guessing attack.

To solve the problem of the low practicability of traditional single keyword searchable encryption10, Park et al.11 proposed two schemes with conjunctive field keyword search. One scheme is more efficient in searching and is reducible to the DBDH (Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman) problem. The other scheme has high encryption efficiency and can be reduced to the DBDHI (Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman Inversion) problem. In order to improve the flexibility of ciphertext retrieval, Boneh et al.12 used hidden vector encryption to propose a searchable encryption scheme that can support subsets, connection and comparison query paradigms. In 2013, Hu et al.13 proposed a public key encryption with ranked multi-keyword search, which enables the server to return only the most relevant k search results. In 2018, Miao et al.14 proposed a verifiable multi-keyword searchable encryption scheme supporting dynamic data owners, and demonstrated that the scheme can resist keyword guessing attacks under the standard model. Wang et al.15 proposed a Inner Product Outsourcing PEKS system (IPO-PEKS) based on LWE assumptions in IoT, which raises search efficiency and achieves more fine-grained searches.

In the above mentioned PEKS schemes, if the retrieved ciphertexts are encrypted by different public keys, the ciphertext cannot be recognized. This means that the PEKS scheme can only achieve keyword search in a single-user environment, and could not meet the practical application.

Public key encryption with equality test

Numerous PKEET schemes have been developed to improve efficiency or expand functionality after Yang et al.’s work3. Tang16,17 introduced a security-enhanced PKEET structure, which added a proxy to the system concept. If a proxy possesses a token generated interactively by two ciphertexts’ recipients, it can execute equality test on them. However, the scheme is inefficient due to the fact that it generates trapdoors through the interaction between the receiver and the tester. Subsequently, Tang18 presented the concept of all-or-nothing PKEET (AoN-PKEET). This means that each user generates authorization trapdoors independently, and the proxy authorized by the user can execute test all ciphertexts of the user. Otherwise, it does not execute tests on any ciphertexts.

Later, Ma et al.19 proposed a new construction with a delegated equality test. Only a proxy is given user authorization and can perform the equality test. Furthermore, they also proposed four types of authorization policies. Huang et al.20 independently presented a PKE structure with an authorized equality test. It enables the user to specify a message set and limits the ability of authorized agents to test ciphertexts that belong to that message set. In the standard model, Zhang et al.21 worked to reduce the computation cost in his PKEET scheme. In addition to less computation, ciphertext and trapdoor sizes have decreased. Additionally, they discuss new structures’ security that don’t rely on random oracles. It was shown that their system is safe under the assumption that the decisional bilinear Diffie-Hellman problem is hard.

Nowadays, with a large number of vehicles connecting to the network and the data volume increasing rapidly, some schemes22,23,24 for cloud-assisted IoV systems are proposed successively. Elhabob et al.22 proposed an efficient certificateless public key encryption scheme with equality test in IoV. Compared with the existing schemes, this scheme has a significant reduction in computational and communication costs. Furthermore, they23 proposed a pairing-free certificateless public key encryption with equality test based on the Diffie - Hellman assumption to solve the problems of integer management, key escrow, and pairing computation. These schemes take into account the application characteristics in the cloud-assisted IoV and the efficiency of the schemes has been improved to a certain extent. However, under the threat of potential quantum computing attacks, these schemes do not possess post-quantum security.

All the schemes mentioned above may become unsafe in a quantum computing environment, because they rely on the difficulty of number-theoretic assumptions. A PKEET scheme based on integer lattice was firstly suggested by Duong et al. in24, and it has been shown to be safe under the standard model if LWE problem still holds. Later, they continued to improve on the previous scheme and achieved CCA2 security. Besides, Duong et al. also proposed a new efficient CCA2-secure PKEET scheme in25, which based on ideal lattices. In 2022, Roy et al.26 construct quantum-safe PKEET schemes over integer lattices and ideal lattices respectively, and both implemented three types of authorization. Xiao et al.27 constructed a lattice-based PKEET scheme, which implemented two authorizations, user-level authorization and designated trusted tester authorization. And the security of the scheme is proved under two different models. Although these lattice-based schemes can resist quantum computing attacks, they all have problems such as low efficiency of algorithm operation and large storage space consumption. And it is very difficult to apply them to the cloud-assisted Internet of Vehicles system with huge amounts of data.

Table 1 summarizes the research status and characteristics of PKEET schemes in recent years from four aspects: hard assumption, security model, application background and resistance to quantum attacks. As shown in Table 1, the new scheme proposed by us is specifically designed for the cloud-assisted Internet of Vehicles system and can achieve post-quantum security.

Motivation and contribution

The historical breakthrough in computing performance brought by quantum computing will break the security of traditional cryptosystems and cause the renewal of cryptographic algorithms. The main objective of this research is to address the issue of secure data sharing among multiple users in cloud computing. Based on lattice cryptography, this paper designs a more compact post-quantum secure lattice cryptography algorithm for data security and privacy protection in the cloud-assisted Internet of Vehicles scenario. The scheme is designed based on the LWE problem on integer lattices and realizes the function of ciphertext equivalence testing, providing a solution for managing encrypted data on the cloud. Furthermore, the study focuses on enhancing algorithmic efficiency and minimizing storage requirements.

A new compact post-quantum secure PKEET scheme for cloud computing is proposed, which is proved to be secure under lattice assumption. Our contribution can be listed into the three categories below:

-

1) In comparison to earlier PKEET schemes, it is compact. Instead of encrypting plaintext’s hash value immediately, we create a less storage cost lattice-based PKEET scheme by incorporating the plaintext’s hash value in the test trapdoor.

-

2) Under the LWE assumption, the new scheme is proved to be secure under the chosen ciphertext attack. Taking the quantum security model into consideration, we also discuss its one-way secure. Because no effective algorithm can solve the LWE problem so far, our approach is characterized as post-quantum safe. In addition, our security model gives the adversary access to quantum computing, which is more powerful than traditional ones. With such efforts, our PKEET scheme provides the possibility for cloud services to resist quantum attacks.

-

3) In order to better illustrate its effectiveness, we implement our new scheme and compare it with a few other lattice-based PKEET schemes. The new scheme uses roughly half the storage space, and the computational overhead during encryption and decryption is cut in half.

Paper organization

In preliminary section, definitions as well as some practical theorems are displayed. In the description of PKEET section, we introduced the system model, formal definition and security model of PKEET. We proposed our new scheme, analyzed its correctness, and proved its security in the proposed lattice-based PKEET scheme section. We evaluate the performance of our constructions based on computational and storage costs. And we also do some comparisons with other schemes in performance evaluation section. Finally, we provided a conclusion in conclusions section.

Preliminaries

Basic notations

Let n, m, q denote positive integers, \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}\) represent the integer ring and \({\mathbf{\mathbb{R}}}\) be the real number. \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q} = {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}/q{\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}\) be the residue class ring. We use bold lowercase letters to represent column vectors. vi represents the i-th entry of a vector v. Bold capital letters represent matrices. For a matrix \({\varvec{A}} \in {\mathbf{{\mathbb{Z}}\ominus }}_{q}^{n \times m}\), it means that a \(m \times n\) matrix on the integer ring. Use \({ \lfloor } \cdot { \rfloor },{ \lceil } \cdot { \rceil },{ \lfloor } \cdot { \rceil }\) to denote downward rounding, upward rounding, and rounding operations respectively. \(x \leftarrow \chi\) denotes a sample from distribution \(\chi\) and \(x\xleftarrow{\$ }\chi\) means sampling randomly. \(\left\| \cdot \right\|\) indicates Euclidean paradigm and \(poly(n)\) indicates a polynomial in n.

Lattice

Definition 1

(Lattice) Given \(n\) linearly independent vectors \({\varvec{b}}_{1} ,{\varvec{b}}_{2} , \cdots {\varvec{b}}_{n} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{m} (m \ge n)\), the lattice is a linear combination of all its integer coefficients, and can be defined as.

\({\varvec{b}}_{1} ,{\varvec{b}}_{2} , \cdots {\varvec{b}}_{n}\) is called as a basis matrix of \({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}})\).

The dimension and rank of lattice \({\mathcal{L}}\) are denoted by the letters m and n, respectively. If m = n, we denote it as a full rank lattice. We consider full rank lattices with \(q{\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}^{m}\), called q-ary lattices. For an integer modulus q and a given matrix \({\varvec{A}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times m}\), they are defined as following:

For an arbitrary \({\varvec{e}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n}\), another construction of \({\mathcal{L}}_{q}^{ \bot } (A)\) is

Definition 2

(Gaussian distribution). For a lattice \({\mathcal{L}} \subseteq {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}^{m}\), for two n-dimensional vectors \(\user2{c,s} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{R}}}^{m}\) and \(\sigma> 0\), we define two equations:

We can define the discrete Gaussian distribution over \({\mathcal{L}}\) centered at c with parameter \(\sigma\) as

where \(\forall {\varvec{x}} \in {\mathcal{L}}.\)

Ajtai28 first proposed an ideal to generate a random lattice \({\mathcal{L}}_{q}^{ \bot } ({\varvec{A}})\) together with an associated small basis of it. The further study in29 improved this algorithm, which we can know in the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Ref29. Let \(q \ge 3\) be odd and \(m: = \left\lceil {6n\log q} \right\rceil .\) \({TrapGen}(q,n)\) denotes a probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) algorithm and outputs \({\varvec{A}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}^{n \times m}\), \({\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{m \times m}\). A is a uniform matrix in \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times m}\) and \({\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}}\) denotes a small basis for \({\mathcal{L}}_{q}^{ \bot } ({\varvec{A}})\) such that \(\left\| {{\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}} } \right\| \le O(\sqrt {n\log q} )\) and \(\left\| {\tilde{\user2{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}} } \right\| \le O(\sqrt {n\log q} )\) in most cases.

Theorem 2

Ref30. Let \(\user2{A,B} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}^{n \times m}\), where \(q> 2,m> n\), and \({\varvec{B}}\) is rank n.\({\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}}\) and \({\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{B}}}\) are basis of \({\mathcal{L}}_{q}^{ \bot } ({\varvec{A}})\) and \({\mathcal{L}}_{q}^{ \bot } ({\varvec{B}})\) correspondingly. Then for \({\varvec{U}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times t}\), there are some useful results:

-

1) For \({\varvec{R}}_{1} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{{n \times m_{1} }}\) and \(\sigma \ge \left\| {\tilde{\user2{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}} } \right\| \cdot \omega (\sqrt {\log (m + m_{1} )} )\), let \({\varvec{F}}_{1} \user2{ = }[\user2{A|R}_{{\varvec{1}}} ]\). There exists a PPT algorithm \({SampleLeft}({\varvec{A}},{\varvec{R}}_{{\varvec{1}}} \user2{,T}_{A} ,{\varvec{U}},\sigma )\) whose output \({\varvec{E}}_{1} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}^{{(m + m_{1} ) \times t}}\), distributes close to \({\mathcal{D}}_{{{\mathcal{L}}_{q}^{{\varvec{u}}} (F_{1} ),\sigma }}\), and satisfies the equation \({\varvec{F}}_{1} \cdot {\varvec{E}}_{1} \user2{ = U }{mod }q\).

-

2) Let \({\varvec{F}}_{2} \user2{ = }\left[ {\user2{A|AR}_{2} \user2{ + B}} \right]\) and \({\varvec{S}}_{{{\varvec{R}}_{2} }} : = \sup_{\left\| x \right\| = 1} \left\| {{\varvec{R}}_{2} {\varvec{x}}} \right\|\), for any matrix \({\varvec{R}}_{2} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{k \times m}\) and \(\sigma> \left\| {\tilde{\user2{T}}_{{\varvec{B}}} } \right\| \cdot S_{{R_{2} }} \cdot \omega (\sqrt {\log m} )\), a PPT algorithm \({SampleRight}({\varvec{A}},\user2{B,R}_{{\varvec{2}}} \user2{,T}_{B} ,{\varvec{U}},\sigma )\) can generate a matrix \({\varvec{E}}_{2} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}^{(m + k) \times t}\) where \({\varvec{S}}_{{{\varvec{R}}_{2} }} : = \sup_{\left\| x \right\| = 1} \left\| {{\varvec{R}}_{2} {\varvec{x}}} \right\|\). The matrix \({\varvec{E}}_{2}\) follows \({\mathcal{D}}_{{{\mathcal{L}}_{q}^{{\varvec{u}}} (F_{2} ),\sigma }}\), and \({\varvec{F}}_{2} \cdot {\varvec{E}}_{2} \user2{ = U }{mod }q\).

If \({\varvec{R}}_{2}\) randomly distributes in \(\left\{ { - 1,1} \right\}^{m \times m}\) then \({\varvec{S}}_{{{\varvec{R}}_{2} }} < O(\sqrt m )\) with overwhelming probability.

Definition 3

(Approximate Shortest Vector Problem (SVPγ)). The SVPγ is to search a nonzero vector \({\varvec{x}} \in {\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}})\), satisfying \(\left\| {\varvec{x}} \right\| \le \gamma \cdot \lambda_{1} ({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}}))\).

Definition 4

(Approximate Shortest Independent Vector Problem (SIVPγ)). The SIVPγ is to search k liner independent \({\varvec{X}} = \left\{ {x_{1} , \cdots ,x_{k} } \right\}\) in \({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}})\), satisfying the formula \(\left\| {{\varvec{x}}_{i} } \right\| \le \gamma \cdot \lambda_{k} ({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}}))\), where \(i = 1,2, \cdots ,k\). And \(\lambda_{k} ({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}}))\) means the \(k{ - }th\) consecutive minimal in lattice \({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}})\).

SVPγ is the core problem of lattice cryptography. For any random lattice \({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}})\), \(\lambda_{1} ({\mathcal{L}}({\varvec{B}}))\) represents the length of the shortest nonzero vector. \(\gamma = \gamma (n) \ge 1\) is an approximation.

Regev31 initially introduced the LWE problem and subsequently developed the first public-key encryption scheme grounded on it. He also provided a quantum reductio ad absurdum argument highlighting the formidable nature of this problem. Our scheme is regarded as secure under the assumption that solving the LWE problem poses significant challenges.

Definition 5

(LWE Distribution31,32). Let prime \(q> 2\), set \(\chi\) as a distribution over \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}\). Consider uniformly s from \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n}\) as a secret, and the LWE distribution \({\mathcal{A}}_{{{\varvec{s}},\chi }}\) is defined as following: \(e\xleftarrow{\$ }\chi\), and output (\({\varvec{a}},b = \left\langle {\user2{a,s}} \right\rangle + {\varvec{e}}\bmod q\)) where vector \({\varvec{a}}\xleftarrow{\$ }{\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n}\).

The search version and the decision version are two distinct forms of LWE. The decision version refers to the distinction between the LWE distribution and the uniform random distribution, while another version means to recover the secret from the LWE sampling. Generally, more samples are needed to determine the unique s.

The rationality of the LWE assumption is based on the difficult problem on the lattice, the SVPγ, SIVPγ problem described previously. It can be argued that the average-case decision LWE problem is polynomially equivalent to its worst-case search version with a certain \(q\)33,34,35. Additionally, the challenge of the decision-version LWE determines how secure our PKEET system is.

Definition 6

(LWE Problem). For a random secret \({\varvec{s}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n}\), choosing m independent samples \({(}{\varvec{a}}_{i} ,b_{i} )\), the \({LWE}_{n,m,q,\alpha }\) problem is to distinguish whether each sample comes from a LWE distribution or a uniform distribution.

In32,36, it was showed that, on average, solving the LWE is at least as difficult as SVPγ and SIVPγ under the quantum reduction model. And its hardness is given by the following Lemma.

Lemma 1

Ref32,36. Consider a discrete Gaussian distribution \(\chi\) whose \(\sigma \ge 2\sqrt m\). For any \(m = poly(n)\), \(q \le 2^{poly(n)}\) and \(\gamma = (n/\alpha )\), SVPγ and SIVPγ on arbitrary n-dimension lattice can be solved if the adversary could address the \({LWE}_{n,q,\chi ,m}\) problem.

The description of PKEET

System model

In the cloud-assisted vehicular environment, in order to ensure safe driving, some users (vehicle terminals) often want to query some useful road information from other users. PKEET technology can ensure that users can obtain the information they need without sacrificing their privacy, which greatly improves the exchange of information and mutual assistance between users. Figure 2 shows the PKEET system model for in cloud-assisted vehicular networks. It contains four main bodies: key generation center, vehicle, users, and cloud server, and each of them performs the functions as described below:

-

• Key Generation Center (KGC): It is primarily used to create and send private keys for users and vehicles securely.

-

• Vehicles: Vehicles receive the keys generated by the KGC. To ensure that no information is exposed, every vehicle encrypts their privacy information firstly, then uploads it to the server. Moreover, vehicles also need to create and upload their own test trapdoors as well.

-

• Users: Users have private keys given by the KGC. When a user in the PKEET system wants to query certain data, he can send an encrypted keyword with a matching trapdoor to the cloud server.

-

• The Cloud Server: It mainly stores the encrypted data of vehicles and perform equality tests when the user queries it. It may compare the data that the user required with the data that is already stored on the server, and feedback the results to the user.

Definition of PKEET

Suppose that there are N users in the PKEET system and each user is indexed by \(i(1 \le i \le N).\) The following five algorithms listed below make up a PKEET system.

-

1) \((pk,sk) \leftarrow {Setup}(\lambda ):\) Give a security parameter \(\lambda\), it outputs a user’s public key \(pk\) and secret key \(sk.\)

-

2) \(c \leftarrow {Enc}(m,pk):\) With the public key \(pk\), it encrypts the plaintext m and generates the ciphertext as c.

-

3) \(m^{\prime} \leftarrow {Dec}(c,pk,sk):\) The input of the decrypt algorithm are public key \(pk\), secret key \(sk\) and ciphertext c, it outputs the decrypted message \(m^{\prime}\) or ⊥.

-

4) \(t_{i} \leftarrow {Td}(pk,sk_{i} ,c):\) For the user \(U_{i}^{{}} ,\) with its secret key \(sk{}_{i}\), public key \(pk\) and the ciphertext c, it outputs a trapdoor \(t_{i}\).

-

5)\(result \leftarrow {Test}(t_{i} ,t_{j} ,c_{i} ,c_{j} ):\) Given two trapdoors \(t_{i}\), \(t_{j}\) and their corresponding ciphertexts \(c_{i}\), \(c_{j}\).

The algorithm can perform equality test and output 1 or 0.

If all the following three conditions are met, we consider a PKEET system to be valid.

1) Let \((pk_{i} ,sk_{i} ) \leftarrow {Setup}(\lambda )\), for any user \(U_{i}^{{}} ,\) and plaintext m, the equation

is satisfied in overwhelming probability.

2) For any user \(U_{i}^{{}}\) and \(U_{j}^{{}} ,\) m is a message, we get \(c_{j} ,t_{j}\) from \((pk_{i} ,sk_{i} ) \leftarrow {Setup}(\lambda )\),\(c_{i} \leftarrow {Enc}(pk_{i} ,m)\) and \(t_{i} \leftarrow {Td}(pk,sk_{i} ,c_{i} ).\) The \(c_{j} ,t_{j}\) are generated by the same algorithms for \(U_{j}^{{}}\). The formula

holds in overwhelm.

3) For any security \(\lambda\) and two different messages \(m_{i} ,m_{j}\), we get \(c_{i} ,c_{j}\) from \(c_{i} \leftarrow {Enc}(pk_{i} ,m_{i} )\) and \(c_{j} \leftarrow {Enc}(pk_{j} ,m_{j} )\). Trapdoors \(t_{i} ,t_{j}\) are generated through the Td algorithm. The formula

holds in negligible.

The security model

The chosen-ciphertext attack in the quantum secure model will be considered here. For this type, an adversary \({\mathcal{A}}\) has access to quantum computing could ask a target user’s trapdoor. Hence it may execute a ciphertext equality test using the test trapdoor. After communicating with the challenger \({\mathcal{C}}\),\({\mathcal{A}}\) seeks to obtain some information from the challenge ciphertext. And we describe a series of interactions called games between \({\mathcal{C}}\) and \({\mathcal{A}}\). If \({\mathcal{A}}\) initiates an attack against the target user \(U_{\theta }\), it will act as following process.

1) Setup: First,\({\mathcal{C}}\) executes \({Setup}(\lambda )\) to receive \((pk_{i} ,sk_{i} )\), where \(i = 1,2, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,N\), and forwards \(pk_{i}\) to \({\mathcal{A}}\) while keeping \(sk_{i}\) itself.

2) Query Phase: \({\mathcal{A}}\) can make the following inquiries adaptively in polynomial times.

\({\mathcal{O}}^{sk}\): An oracle that output the secret key \(sk_{i}\) of \(U_{i}\) when given an index \(i\), and \(i\) is different from \(\theta\).

\({\mathcal{O}}^{Dec}\): When a decryption query is issued, the decryption result can be obtained by entering a random ciphertext \(c_{i}\), the public key \(pk_{i}\) and the secret key \(sk_{i}\) with the algorithm \({Dec}(c_{i} ,pk_{i} ,sk_{i} )\).

\({\mathcal{O}}^{t}\): Given the secret key \(sk_{i}\) of \(U_{i}^{{}}\), public key \(pk_{i}\) and ciphertext \(c_{i}\), \({\mathcal{O}}^{t}\) returns \(t_{i}\) by executing Td algorithm.

3) Challenge: By choosing m randomly, \({\mathcal{C}}\) runs algorithm \(c_{\theta }^{*} \leftarrow {Enc}(pk_{\theta } ,m)\) and gives \(c_{\theta }^{*}\) to \({\mathcal{A}}\).

4) Guess: After receiving the ciphertext \(c_{\theta }^{*}\) from the target \(U_{\theta }\), \({\mathcal{A}}\) outputs its guess \(m^{\prime}\). When \(m = m^{\prime}\), we consider the quantum adversary \({\mathcal{A}}\) has won the OW-CCA game. And the following equation represents the probability of a successful attack issued by \({\mathcal{A}}\).

Consequently, if the quantum adversary \({\mathcal{A}}\) has a negligible chance of succeeding in the game described above, a PKEET system can be considered post-quantum secure under an OW-CCA attack.

The proposed lattice-based PKEET scheme

We introduce an efficient PKEET scheme under integer lattice and analyze its correctness in this subsection. Additionally, using the quantum security model, we demonstrate that the construction is one-way secure and can withstand the chosen ciphertext attacks under LWE assumption.

Proposed construction

\({Setup}(\lambda ):\) Let \(\lambda ,n,m\) and \(q\) be defined as in Theorem 1.

1)\({TrapGen}(q,n)\) generates a uniformly random matrix \({\varvec{A}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}^{n \times m}\) together with a trapdoor \({\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{m \times m}\).

2) Sample matrices \({\varvec{A}}_{1} \user2{,B}\) from \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times m}\) uniformly random.

3) Sample a matrix \({\varvec{U}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{{^{n \times k} }}\) randomly.

4) Choose hash function \(H:\left\{ {0,1} \right\}^{*} \to \left\{ {0,1} \right\}^{k}\).

5) Output \(\user2{pk = }\left\{ {\user2{A,A}_{1} \user2{,B,U}} \right\}\),\(\user2{sk = T}_{{\varvec{A}}}\).

\({Enc}({\varvec{m}},{\varvec{pk}}):\) With \(\user2{pk = }\left\{ {\user2{A,A}_{1} \user2{,B,U}} \right\}\), \({\varvec{m}} \in \left\{ {0,1} \right\}^{k}\).

1) Keep sampling \({\varvec{s}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n}\) randomly, until its first component \(s_{1} \ne 0\).

2) Choose \({\varvec{R}} \in \left\{ { - 1,1} \right\}^{m \times m}\) randomly.

3) Select \({\varvec{x}}\xleftarrow{\$ }{\mathcal{D}}_{\updelta }^{k}\) and \({\varvec{y}}\xleftarrow{\$ }{\mathcal{D}}_{\updelta }^{m}\) with the deviation \(\delta> 0\). \({\mathcal{D}}_{\updelta }^{k}\) and \({\mathcal{D}}_{\updelta }^{m}\) are discrete Gaussian distribution.

4) Set \(\user2{F = }\left( {\user2{A|A}_{{\varvec{1}}} + {\varvec{B}}} \right) \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times 2m}\).

5) Compute

6) Output the ciphertext \({\varvec{c}}\) as \(\left( {{\varvec{c}}_{1} ,{\varvec{c}}_{2} ,s_{1} } \right)\).

\({Dec(}\user2{pk,sk,c}):\) On input \(\user2{pk = }\left\{ {\user2{A,A}_{1} \user2{,B,U}} \right\}\), \(\user2{sk = T}_{{\varvec{A}}}\) and a ciphertext \({\varvec{c}}\) as \(\left( {{\varvec{c}}_{1} ,{\varvec{c}}_{2} ,s_{1} } \right)\), it does:

1) Run \({SampleLeft}({\varvec{A}},{\varvec{A}}_{1} \user2{ + B,T}_{A} ,{\varvec{U}},\sigma )\) to generate \({\varvec{E}}_{1} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{2m \times k}\), satisfying \({\varvec{F}} \cdot {\varvec{E}}_{1} \user2{ = U }{mod }q\).

2) Compute \({\varvec{v}} = {\varvec{c}}_{1} - {\varvec{E}}_{1}^{T} \cdot {\varvec{c}}_{2} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{k}\).

3) For each \(i = 1,2, \cdots ,k\), compare \(v_{i}\) and \({ \lfloor }\frac{q}{2}{ \rfloor }\). If the value \(\left| {v_{i} - { \lfloor }\frac{q}{2}{ \rfloor }} \right| < \frac{q}{4}\), \(m_{i} = 1\), otherwise \(m_{i} = 0\).\(v_{i}\) is the i-th component of \({\varvec{v}}\).

4) Output the plaintext as \({\varvec{m}}\).

\({Td(}\user2{pk,sk,c,}H{(}{\varvec{m}})):\) With \(\user2{pk = }\left\{ {\user2{A,A}_{1} \user2{,B,U}} \right\}\), \(\user2{sk = T}_{{\varvec{A}}}\), \({\varvec{c}}{ = }\left( {{\varvec{c}}_{1} ,{\varvec{c}}_{2} ,s_{1} } \right)\), phrase \(H({\varvec{m}})\user2{ = }(H({\varvec{m}})_{1} , \cdots ,H({\varvec{m}})_{k} ) \in \left\{ {0,1} \right\}^{k}\).

1) Compute \(w_{i} \user2{ = }H({\varvec{m}})_{i} \cdot { \lfloor }\frac{q}{2}{ \rceil } \cdot s_{{_{1} }}^{ - 1} { mod }q\).

2) Let \({\varvec{W}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times k}\) be \(\user2{W = }\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {w_{1} } & {w_{2} } & \cdots & {w_{k} } \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ \end{array} } \right)\).

3) Run \({SampleLeft}({\varvec{A}},{\varvec{A}}_{1} \user2{ + B,T}_{A} ,{\varvec{W}},\sigma )\) and obtain \({\varvec{E}}_{2} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{2m \times k}\), such that \({\varvec{F}} \cdot {\varvec{E}}_{2} \user2{ = W }{mod }q\).

4) Output trapdoor as \({\varvec{E}}_{2} { }\).

\({Test(}\user2{t,t^{\prime},c,c^{\prime}}):\) On input ciphertexts \(\user2{c = }\left( {{\varvec{c}}_{1} ,{\varvec{c}}_{2} ,{\varvec{s}}_{{\varvec{1}}} } \right)\), \(\user2{c^{\prime} = }\left( {{\varvec{c}}_{1}^{\user2{^{\prime}}} ,{\varvec{c}}_{2}^{\user2{^{\prime}}} ,{\varvec{s}}_{1}^{\user2{^{\prime}}} } \right)\) and trapdoors \(\user2{t = E}_{2}\), \(\user2{t^{\prime} = E}_{{_{2} }}^{\user2{^{\prime}}}\) from different users.

1) Compute \(\user2{hv = E}_{{\varvec{2}}}^{T} \cdot {\varvec{c}}_{{\varvec{2}}}\) and \(\user2{hv^{\prime} = E}_{{\varvec{2}}}^{{\user2{^{\prime}}T}} \cdot {\varvec{c}}_{{\varvec{2}}} \user2{^{\prime}}\).

2) For \(i = 1,2, \cdots ,k\), \({\varvec{hm}}\) is generated by the following way: set \(hm_{i} = 0\) if the value \(\left| {hv_{i} - { \lfloor }\frac{q}{2}{ \rceil }} \right|\) is less to \(\frac{q}{4}\) and \(hm_{i} = 1\) otherwise. \({\varvec{hm}}^{\prime}\) can be created in a similar manner.

3) Output 1 when \(\user2{hm = hm}^{\prime}\), 0 otherwise.

Correctness

Due to the adoption of a collision-resistant hash function in the encryption process, the PKEET scheme can effectively decrypt and perform ciphertext equivalence testing operations. The following elucidates this in terms of decryption correctness and testing validity.

Theorem 3

If H used in our PKEET scheme is collision resistant hash function and parameters are selected as above, the construction is correct.

Proof

As v is rewritten in a certain way, it can be.

where \({\varvec{x}} - {\varvec{E}}_{1}^{T} \cdot \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\varvec{y}} \\ {{\varvec{y}}^{\prime}} \\ \end{array} } \right)\) is the error term. When related parameters are selected felicitously, it has been proved that the error norm is always less than \({ \lfloor }\frac{q}{5}{ \rceil }\) in most cases in30. Therefore, the algorithm usually outputs the correct plaintext.

Then, we account for the correctness of the equality test.

For \(w_{i} \user2{ = }H({\varvec{m}})_{i} \cdot { \lfloor }\frac{q}{2}{ \rceil } \cdot s_{{_{1} }}^{ - 1} { mod }q\), we defined a matrix as.

\(\user2{W = }\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {w_{1} } & {w_{2} } & \cdots & {w_{k} } \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ \end{array} } \right)\).

For \(\user2{hv = E}_{{\varvec{2}}}^{T} \cdot {\varvec{c}}_{{\varvec{2}}} = {\varvec{W}}^{T} \cdot {\varvec{s}} + {\varvec{E}}_{2}^{T} \cdot \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\varvec{y}} \\ {{\varvec{y}}^{\prime}} \\ \end{array} } \right),\) the equation can be rewritten as

Because \({\varvec{E}}_{2}^{T}\) is generated in the same way as \({\varvec{E}}_{1}^{T}\), the norm of \({\varvec{E}}_{2}^{T} \cdot \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\varvec{y}} \\ {{\varvec{y}}^{\prime}} \\ \end{array} } \right)\) is less to \({ \lfloor }\frac{q}{5}{ \rceil }\) under the same parameters. Moreover, in Test algorithm, the calculation of \({\varvec{hm}}\) is equal to \(H({\varvec{m}})\), as well as \(\user2{hm^{\prime}}\). Because the hash function is a collision resistant, we will have \(\user2{hm = hm^{\prime}}\) only when \(\user2{m = m^{\prime}}\).

Security analysis

We discuss the post-quantum security of our lattice-based PKEET scheme in this part. Before that, we first revisited a useful result called the leftover hash lemma37.

Lemma 2

Ref37. Let \(q> 2\) be a prime, \(k = poly(n)\) and \(m> (n + 1)\log q + w(\log n)\), \((\user2{A,B,R}^{T} {\varvec{e}})\) distributes closely to \((\user2{A,AR,R}^{T} {\varvec{e}})\) if we sample uniformly \(\user2{A,B} \leftarrow {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times m}\), \({\varvec{R}} \leftarrow \left\{ { - 1,0,1} \right\}^{m \times k}\) at random, and e sampled from \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{m}\) randomly.

Remark

As is introduced in18, we considered \(h_{{{\varvec{A}}({\varvec{x}})}} \user2{ = Ax }\bmod q\) as a universal hash function. Moreover, Agrawal et al.30 has also proved it is hard to distinguish between \((\user2{A,AR})\) and \((\user2{A,B})\) for any PPT adversary, although some information as \({\varvec{R}}^{T} {\varvec{e}}\) is revealed.

Theorem 4

Ref38. The lattice-based PKEET scheme proposed above is OW-CCA secure when it fulfills the following two conditions:

-

• LWE assumption holds.

-

• H is a one-way hash function.

Proof

We will use several games to prove that the adversary with quantum computing could not distinguish one game from another in PPT. Otherwise, neither the LWE problem assumption nor Lemma 1 won’t hold.

Game 0: This is the original OW-CCA game defined as the security model before. And it is between a quantum attacker \({\mathcal{A}}\) and an OW-CCA challenger \({\mathcal{C}}\).

Game 1: Let \(i^{*} \in \left[ {1,t} \right]\) denote the target user’s index. After answering some inquiries from \({\mathcal{A}}\), \({\mathcal{C}}\) samples R* from \(\left\{ { - 1,1} \right\}^{m \times m}\) randomly and generates the challenge ciphertext c*. Then it obtains matrices A, \({\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{A}}}\), and B by algorithm \({Setup}(\lambda )\) as in Game 0. In this game, we made some modifications to change the method of constructing the matrix \({\varvec{A}}_{1}\) as \({\varvec{A}}_{1} \leftarrow {\varvec{A}} \cdot {\varvec{R}}^{*}\). And the remainder part is identical to the Game 0.

According to the encryption algorithm described above, \(\user2{y^{\prime}}\) is calculated from equation \(({\varvec{R}}^{*} )^{T} \cdot {\varvec{y}}\). Because on the Lemma 2, \((\user2{A,AR}^{*} ,\user2{y^{\prime}})\) distributes closely to \((\user2{A,A^{\prime}},\user2{y^{\prime}})\), and \(\user2{A^{\prime}}\) is a random matrix in \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times m}\). In that case, \({\varvec{AR}}^{*}\) distributes closely to uniform distribution, so does \({\varvec{A}}_{1}\). The adversary can hardly distinguish them, which means that Game 1 is identical to Game 0 in an adversary’s view. Furthermore, it indicates that \({\mathcal{A}}\) could not distinguish between two games by non-negligible advantage.

Game 2: It behaved the same as Game 1 except \({\mathcal{C}}\) generate a special public key for the target user. Concretely speaking, the way to generate matrix \({\varvec{A}}\) and \({\varvec{B}}\) is different. \({\mathcal{C}}\) generates \((\user2{B,T}_{{\varvec{B}}} )\) by running the algorithm \({TrapGen}\), while \({\varvec{A}}\) is sampled from \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times m}\) randomly. \({\varvec{A}}_{1}\) is generated the same as Game 1.

With these changes, \({\mathcal{C}}\) can answer user’s queries on \({\varvec{sk}}\). When asked for \({\varvec{sk}}\) of the target user \(i^{*}\), \({\mathcal{C}}\) returns trapdoor \({\varvec{T}}_{{\varvec{B}}}\). When asked for other user’s \({\varvec{sk}}\), \({\mathcal{C}}\) chooses to output the trapdoor \({\varvec{T}}_{i}\) by execute algorithm \({SampleRight}\), where

In this situation, the challenger \({\mathcal{C}}\) will run the algorithm \({SampleRight}({\varvec{A}},\user2{B,R}^{*} \user2{,T}_{B} ,\sigma )\) to generate \({\varvec{T}}_{i}\). Although the way that \({\mathcal{C}}\) generates the target user’s private key is different in the above two games, it is hard for an attacker to notice this modification. The reason is the output of algorithm \({SampleLeft}\) and \({SampleRight}\) follows the same distribution. Hence, any PPT adversary can hardly distinguish Game 1 from Game 2.

Game 3: Let \(\left( {{\varvec{c}}_{1}^{*} ,{\varvec{c}}_{2}^{*} ,s_{1} } \right)\) be random independent element in \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{t} \times {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{2m} \times \left\{ {{\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q} \backslash \left\{ 0 \right\}} \right\}\), which is different from Game 2. The remaining parts are unchanged from the previous game. Under the circumstances, the probability of successfully guessing the plaintext m is very small, about \(1/2^{t}\). Furthermore, there is even less advantage than it to win the OW-CCA game for \({\mathcal{A}}\).

Finally, we will show that any PPT adversary even though it may have access to quantum computers, could hardly notice the difference between the last two games. Or else, LWE assumption won’t hold any more.

Reduction from LWE. Suppose \({\mathcal{A}}\user2{^{\prime}}\) has a non-negligible advantage in distinguishing the last two games. By making \({\mathcal{A}}\user2{^{\prime}}\) as an oracle, we construct an efficient solver \({\mathcal{B}}\). By given \((m + t)\) samples \(\left( {{\varvec{u}}_{{_{i} }}{\prime} ,w_{i}{\prime} } \right) \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n - 1} \times {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}\), if \({\mathcal{B}}\) can judge these samples are from LWE distribution or truly random distribution for some fixed secret s. Assuming \({\mathcal{B}}\) solves the LWE problem, it works as follows:

Setup. \(\left( {{\varvec{u}}_{{_{i} }}{\prime} ,w_{i}{\prime} } \right) \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n - 1} \times {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}\) are all LWE samples for \(i = 1,2, \cdots ,m,m + 1, \cdots m + k\).\({\mathcal{A}}\user2{^{\prime}}\) chooses its target user’s index \(\theta (1 < \theta < N)\) and send it to \({\mathcal{B}}\). By using those \((m + k)\) samples, the generation of \({\varvec{pk}}_{\theta }\) is changed into:

-

1) Choose \(u_{i} ,s_{1} \leftarrow {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}\) randomly and \(s_{1} \ne 0\), define \({\varvec{u}}_{i} = (u^{i} \user2{|u}_{{_{i} }}{\prime} ) \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{{_{q} }}^{n}\) and \(v_{{^{i} }} = v_{i}{\prime} + u_{i} s_{1}\).

-

2) The random matrix \({\varvec{A}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times m}\) is generated as \({\varvec{A}} = \left[ {{\varvec{u}}_{1} ,{\varvec{u}}_{2} , \cdots ,{\varvec{u}}_{m} } \right]\).

-

3) The random matrix \({\varvec{U}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n \times k}\) is denoted as \({\varvec{U}} = \left[ {{\varvec{u}}_{m + 1} , \cdots ,{\varvec{u}}_{m + k} } \right]\).

-

4)\({\varvec{A}}_{1} \user2{,B}\) is constructed the same as in Game 2.

-

5) Set \({\varvec{pk}}_{\theta } = \left\{ {\user2{A,A}_{1} \user2{,B,U}} \right\}\) to \({\mathcal{A}}\user2{^{\prime}}\).

Queries. In order to response the queries of \({\varvec{sk}}_{i}\) for every user, \({\mathcal{B}}\) executes the same procedure as in Game 2.

Challenge. In response to the user’s private key query, \({\mathcal{B}}\) simply need to executes algorithm \({SampleRight}\) as in Game 2. For the target plaintext \({\varvec{m}}^{*} \in \left\{ {0,1} \right\}^{k}\), the challenge ciphertext \({\varvec{ct}}^{*}\) is constructed as below.

1) For \(i = 1,2, \cdots ,m,\)\({\varvec{w}}^{*} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{m}\) is generated as \({\varvec{w}}^{*} = \left[ {{\varvec{w}}_{1} , \cdots ,{\varvec{w}}_{m} } \right]\).

2) For \(i = m + 1, \cdots ,m + k,\)\({\varvec{w}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{t}\) is generated as \({\varvec{w}} = \left[ {{\varvec{w}}_{m + 1} , \cdots ,{\varvec{w}}_{m + k} } \right]\).

3) Choose the matrix \({\varvec{R}}^{*}\) the same as in Game 2.

Compute \({\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,1}^{*} = \user2{w + m}^{*} { \lfloor }\frac{q}{2}{ \rceil }\) and \({\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,2}^{*} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\varvec{w}}^{*} } \\ {({\varvec{R}}^{*} )^{T} {\varvec{w}}^{*} } \\ \end{array} } \right).\)

4)\({\varvec{s}}_{1}^{*}\) and \({\varvec{s}}_{1}\) are set up the same.

5) Let \(b\xleftarrow{\$ }\left\{ {0,1} \right\}\). If \(b = 0\), set \({\varvec{ct}}^{*}\) as random element in \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{t} \times {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{2m} \times \left\{ {{\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q} \backslash \left\{ 0 \right\}} \right\}\). Or else, set \({\varvec{ct}}^{*}\) as \(({\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,1}^{*} ,{\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,2}^{*} ,s_{1}^{*} )\). Then, send \({\varvec{ct}}^{*}\) to \({\mathcal{A}}{\prime}\).

Let \({\varvec{y}}\xleftarrow{\$ }{\mathcal{D}}_{\updelta }^{m}\) and \(\user2{s = }\left( {s_{{1}} |\user2{s^{\prime}}} \right)\), the equation \({\varvec{w}}^{*} = {\varvec{A}}^{T} \user2{s + y}\) will hold if \(\left\{ {{\varvec{u}}_{{_{i} }}{\prime} ,v^{i} } \right\}_{i = 1}^{{m{ + }t}}\) are all sampled from LWE distribution. Since \({\varvec{F}}_{\theta }^{*} \user2{ = }(\user2{A|AR}^{*} )\), \({\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,2}^{*}\) can be rewrote as

The vector \({\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,1}^{*}\) is equal to \({\varvec{U}}^{T} \cdot \user2{s + x + m} \cdot \frac{q}{2}\) and \({\varvec{x}}\) denotes the error term of the last \(t\) LWE samples. Thus, \({\varvec{ct}}_{\theta }^{*} \left( {{\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,1}^{*} ,{\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,2}^{*} ,s_{1}^{*} } \right)\) is identical to that in Game 2.

If \(\left\{ {{\varvec{u}}_{{_{i} }}{\prime} ,v^{i} } \right\}_{i = 1}^{{m{ + }t}} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n - 1} \times {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}\) distributes randomly, \({\varvec{c}}_{\theta ,2}^{*} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{2m}\) constructed above is also randomly distributed because of the Lemma 2. Therefore, \({\varvec{ct}}_{\theta }^{*}\) is also uniform and independent, which is the same as Game 3.

Guess. After receiving the challenge ciphertext \({\varvec{ct}}_{\theta }^{*}\) and making some queries, the adversary \({\mathcal{A}}\) will guess which game it is interacting with. In the end, B will answer the LWE problem according to \({\mathcal{A}}\user2{^{\prime}}\) guess.

Given that the assumptions of the LWE problem and the residual hash lemma hold, the adversary is unable to distinguish between the two games in probabilistic polynomial time. Therefore, the aforementioned scheme is OW-CCA secure.

Performance evaluation

The scheme presented in24 represents the first lattice-based PKEET scheme, while the scheme in26 and27 stand out as prominent choices in recent years. By comparing our PKEET scheme based on integer lattices with these references, we can clearly observe that our system is computationally less expensive and requires smaller parameter sizes.

Computation cost

We compare the computational efficiency of the schemes from two aspects: theoretical calculations and actual running time of algorithms. Before the theoretical analysis, we define several symbols as follows.

-

•\(T_{SL}\): It represents the computation cost of the algorithm \({SampleLeft}\).

-

•\(T_{SD}\): It represents the computation cost of the algorithm \({SampleD}\).

-

•\(T_{H}\): It represents the cost of executing hash operation on m.

-

•\(T_{\delta }\): The time cost on sampling a vector from \({\mathcal{D}}_{\delta }^{m}\).

-

•\(T_{A}\): It represents the cost taken for the addition operation between vectors.

-

•\(T_{M}\): It denotes the computational time consumed by multiplication operations between a matrix and a vector.

Four lattice-based PKEET schemes are computed and analyzed using the above defined symbols. The computational overheads of each scheme in the encryption phase, decryption phase, and testing phase are shown in Table 2. The analysis of the PKEET scheme shows that the designed new scheme needs to perform two Gaussian samples, four modulo additions and three modulo multiplications in the encryption phase. In the decryption phase, only need to run the SampleLeft algorithm once, followed by one modular addition and one modular multiplication. Compared with the schemes in References24,26 and27, the computational consumption of the newly proposed scheme in the encryption and decryption stages is reduced by more than half. The rest comparisons are also depicted in Table 2. In the testing phase, the performance of the new scheme still needs to be further evaluated through experiments.

For different application scenarios, the selection of parameter values determines the performance and security of schemes. Here, n denotes the lattice dimension, which is associated with the key length. Generally, a larger n enhances security, but an excessively large n may reduce efficiency. m represents the number of samples, typically requiring m>n. In order to facilitate the subsequent experimental comparison between various schemes, the recommended parameter choices under different security strengths are shown in Table 3. The values of these parameters are only general recommendations, and in actual application, comprehensive consideration is needed based on other conditions.

The performance analysis are carried out on a personal computer (windows 10 pro operating system with Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-13900 CPU @2.20 GHz and 32GB RAM and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU@8GB). Using the recommended parameter values under different security in Table 3, each algorithm is implemented and the running time is calculated by python programming. Given algorithmic variability, results in Table 4 reflect the average of 1,000 runs (in milliseconds).

From the experimental results in Table 4, it can be observed that the execution time of each algorithm increases with the growth of n. Under equivalent security levels, the encryption and decryption algorithms of our scheme demonstrate higher efficiency and the shortest execution times among all compared schemes. Specifically, our scheme outperforms the one in Ref24. by approximately 74.75% and 50% in encryption and decryption efficiency, respectively, and surpasses the scheme in Ref27. by around 69.93% and 72.47%.

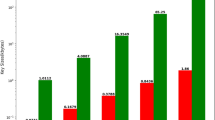

To more clearly compare the efficiency of encryption, decryption, and testing algorithms across different schemes, the experimental data in Table 4 is visualized as a bar chart. Figures 3, 4, and 5 illustrate the actual execution times of each algorithm in various schemes when n is set to 64, 128, and 256, respectively. It is clear that the scheme proposed herein achieves the minimum execution time for both encryption and decryption processes, showcasing higher algorithmic efficiency.

Storage Cost

By computing the quantity of elements in \({\mathbf{\mathbb{Z}}}_{q}^{n}\), we compare these scheme’s space cost and analyze each parameter’s size. As is shown in Table 5, most of the parameter sizes including \(pk\),\(sk\) and \(ct\) of ours are much smaller than those in the others’ scheme. To be specific, the size of ciphertext is about half the storage space compared to Duong et al.’s scheme24, which is also smaller than another lattice-based schemes. When we focus on the secret key, it is about half smaller than Duong et al.’s scheme24 and Roy et al.’s scheme26.

In order to make a more intuitive comparison of the storage space consumed by different schemes, we assign values to each parameter as shown in Table 3. Since \(l\) is a positive integer, we assume \(l \ge 3\). The storage space consumed in our scheme can be estimated by the following calculation. When n = 64, we estimated the public key \(pk\) by \((3mn + nk)\left\lceil {\log q} \right\rceil = 0.29\) Mb, the secret key \(sk\) by \(m^{2} \left\lceil {\log q} \right\rceil = 1.74\) Mb, and the ciphertext \(ct\) by \((2m + k + 1)\left\lceil {\log q} \right\rceil = 3.12\) Kb.

The consumption of storage space for the other three schemes is also evaluated in this way for the calculation. The final results are summarized in Table 6. When compared with the integer lattice-based schemes in Refs24. and26, the proposed scheme demonstrates the smallest storage overhead for public keys, private keys, and ciphertexts across all tested values of n. The private key size of our scheme is approximately half that of the schemes in Refs24. and26, though slightly larger than that in Ref27.. It also indicates that the storage consumption of our scheme is minimized for ciphertext. Notably, the sizes of public keys, private keys, and ciphertexts in all schemes increase as the security level rises.

Conclusions

In order to improve efficiency, meet practical application requirements, and resist quantum computing attacks, we presented a compact lattice-based PKEET scheme. By embedding the hash value of the plaintext into the test trapdoor, its ciphertext size is smaller, and the storage space is greatly saved. We proved that our new scheme could resist the chosen ciphertext attacks and is one-way secure in the quantum secure model. Furthermore, we evaluated the performance of the new scheme. The results indicate that the ciphertext and key size of the new scheme are smaller, and the execution time of the encryption and decryption phases is reduced by nearly half. Through comparison, it is found that our scheme has significant advantages in the integer lattice - based PKEET scheme.

In future work, our PKEET scheme can be further improved through the following methods. The ideal lattice is a lattice defined based on the polynomial ring algebraic structure. When converting the algorithm, each element of the integer vector in the original algorithm needs to be mapped to a polynomial in the polynomial ring according to certain rules. For each step in the encryption algorithm, corresponding adjustments need to be made according to the characteristics of the ideal lattice. For example, the output of the hash function needs to be converted into a polynomial to adapt to the ideal lattice structure. After the algorithm expansion is completed, the security of the new algorithm based on the ideal lattice also needs to be verified. By means of reduction proof, it is reduced to the learning with errors problem on the ideal lattice. Overall, converting the integer lattice - based PKEET algorithm in this paper into an ideal lattice - based algorithm is theoretically feasible. It can bring improvements in algorithm efficiency and storage consumption. Expanding the scheme in this paper to the ideal lattice is the goal of our next step of work.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Gentry C (2009) Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices. In: Proceedings of the forty-first annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, Bethesda, USA, 31 May, (2009).

Boneh D, Crescenzo G D, Ostrovsky R, Persiano G (2004) Public key encryption with keyword search. In: Advances in Cryptology-EUROCRYPT, Interlaken, Switzerland, 2–6 May, (2004).

Yang G, Tan C H, Huang Q, Wong D S (2010) Probabilistic public key encryption with equality test. In: Topics in Cryptology-CT-RSA, San Francisco, USA, 1–5 March, (2010).

Zhao, Y., Hou, Y., Chen, Y., Kumar, S. & Deng, F. An efficient certificateless public key encryption with equality test toward Internet of Vehicles. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 33(5), e3812 (2022).

Bellare, M., Namprempre, C. & Neven, G. Efficient Certificateless Public Key Cryptography with Equality Test for Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Access 7, 68957–68969 (2019).

Shor P W (1994) Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In: Proceedings 35th annual symposium on foundations of computer science, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–22 November, (1994).

Byun J W, Rhee H S, Park H A, Lee D H (2006) Off-Line Keyword Guessing Attacks on Recent Keyword Search Schemes over Encrypted Data. In: Workshop on secure data management, Seoul, Korea, 10–11 September, (2006).

Tang Q, Chen L (2009) Public-Key Encryption with Registered Keyword Search. In: European public key infrastructure workshop, Berlin, Pisa, Italy, 10–11 September, (2009).

Xu, P., Jin, H. & Wu, Q. Public-Key Encryption with Fuzzy Keyword Search: A Provably Secure Scheme under Keyword Guessing Attack. IEEE Trans. Comput. 62(11), 2266–2277 (2012).

Chang Y C, Mitzenmacher M (2004) Privacy Preserving Keyword Searches on Remote Encrypted. In: International conference on applied cryptography and network security, New York, NY, USA, 7–10 June, (2004).

Park D J, Kim K, Lee P J (2004) Public key encryption with conjunctive field keyword search. In: International Workshop on Information Security Applications, Jeju Island, Korea, 23–25 August, (2004).

Boneh D, Waters B (2007) Conjunctive, subset, and range queries on encrypted data. In: 4th Theory of Cryptography Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 21–24 February, (2007).

Hu C, Liu P (2013) Public key encryption with ranked multi-keyword search. In: 5th International Conference on Intelligent Networking and Collaborative Systems, Xi’an, China, 9–11 September, (2013).

Miao, Y., Ma, J. & Liu, X. Verifiable multi-keyword search over encrypted cloud data for dynamic data-owner. Peer-to-peer Netw. Appl. 11(2), 287–297 (2018).

Wang, M., Sun, L., Cao, Z. & Dong, X. IPO-PEKS: Effective inner product outsourcing public key searchable encryption from lattice in the IoT. IEEE Access 12, 28926–28937 (2024).

Tang Q (2011) Towards public key encryption scheme supporting equality test with fine-grained authorization. In: Australasian conference on information security and privacy, Melbourne, Australia, 11–13 July, (2011).

Tang, Q. Public key encryption schemes supporting equality test with authorisation of different granularity. Int. J. Appl. Cryptogr. 2(4), 304–321 (2012).

Tang, Q. Public key encryption supporting plaintext equality test and user-specified authorization. Secur. Commun. Netw. 5(12), 1351–1362 (2012).

Ma, S., Zhang, M., Huang, Q. & Yang, B. Public key encryption with delegated equality test in a multi-user setting. Comput. J. 58(4), 986–1002 (2015).

Huang K; Chen Y C; Tso R (2015) Semantic secure public key encryption with filtered equality test (PKE-FET). In: 12th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications, Colmar, France, 20–22 July, (2015).

Zhang, K., Chen, J., Lee, H. T., Qian, H. & Wang, H. Efficient public key encryption with equality test in the standard model. Theoret. Comput. Sci. 755, 65–80 (2019).

Elhabob, R., Zhao, Y., Sella, I. & Xiong, H. Efficient certificateless public key cryptography with equality test for internet of vehicles. IEEE Access 7, 68957–68969 (2019).

Elhabob, R. et al. Pairing-free certificateless public key encryption with equality test for Internet of Vehicles. Comput. Electr. Eng. 116, 109140 (2024).

Duong D H, Fukushima K, Kiyomoto S, Roy P S, Susilo W (2019) A Lattice-Based Public Key Encryption with Equality Test in Standard Model. In: 24th Australasian Conference on Information Security and Privacy, Christchurch, New Zealand, 3–5 July, (2019).

Duong, D. H. et al. Chosen-ciphertext lattice-based public key encryption with equality test in standard model. Theoret. Comput. Sci. 905, 31–53 (2022).

Roy, P. S. et al. Lattice-based public-key encryption with equality test supporting flexible authorization in standard model. Theoret. Comput. Sci. 929, 124–139 (2022).

Xiao, K., Chen, X., Huang, J., Li, H. & Huang, Q. A lattice-based public key encryption scheme with delegated equality test. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 87, 103758 (2024).

Ajtai M (1999) Generating hard instances of the short basis problem. In: Automata, Languages and Programming: 26th International Colloquium, Prague, Czech Republic, 11–15 July, (1999).

Alwen J, Peikert C (2009) Generating shorter bases for hard random lattices. In: 26th International Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Computer Science, Freiburg, Germany, 26–28 February, (2009).

Agrawal S, Boneh D, Boyen X (2010) Efficient lattice (H)IBE in the standard model. In: 29th Annual International Conference on Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Riviera, French, 30 May-3 June, (2010).

Regev O (2005) On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography. In: 37th annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, Baltimore, MD, USA, 22–24 May, (2005).

Regev, O. On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography. J. ACM 56(6), 1–40 (2009).

Ateniese G, Camenisch J, Joye M, Tsudik G (2000) A practical and provably secure coalition-resistant group signature scheme. In: 20th Annual International Cryptology Conference Santa Barbara, California, USA, 20–24 August, (2000).

Camenisch J; Lysyanskaya A (2004) Signature schemes and anonymous credentials from bilinear maps. In: 24th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, California, USA, 15–19 August, (2004).

Canetti R, Halevi S, Katz J (2004) Chosen-ciphertext security from identity-based encryption. In: International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Interlaken, Switzerland, 2–6 May, (2004).

Gordon S D, Katz J, Vaikuntanathan V (2010) A group signature scheme from lattice assumptions. 16th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Singapore, 5–9 December, (2010).

Dodis, Y., Ostrovsky, R., Reyzin, L. & Smith, A. Fuzzy extractors: How to generate strong keys from biometrics and other noisy data. SIAM J. Comput. 38(1), 97–139 (2008).

Yang, Z., He, D., Qu, L. & Ye, Q. An Efficient Identity-Based Encryption with Equality Test in Cloud Computing. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 11(3), 2983–3299 (2023).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 62202490, 62276273, and 62102440.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junfei He: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Original draft preparation. Qing Ye: Resources, Writing-Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. Zhichao Yang: Conceptualization, Verifica-tion, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Shixiong Wang: formal analysis, funding acquisition. Jiasheng Wang: data curation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, J., Ye, Q., Yang, Z. et al. A compact public key encryption with equality test for lattice in cloud computing. Sci Rep 15, 27426 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12018-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12018-2