Abstract

Inflammation has been recognized as a pivotal factor in the pathophysiology of diabetes. The aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) has recently been proposed as a novel biomarker for evaluating inflammatory status and predicting clinical outcomes. However, evidence on the association between AISI and mortality in diabetic patients remains limited. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to investigate the association between AISI and mortality risk from cardio-cerebrovascular disease (CCD) and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients. We analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES, 2001–2018). Multivariable-adjusted Cox models revealed strong associations between elevated AISI levels and CCD mortality (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.11–1.26) as well as malignant neoplasm mortality (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.10–1.30). Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that higher AISI was associated with lower survival in diabetic patients for both CCD and malignant neoplasms. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis demonstrated an increased risk of mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients with elevated AISI levels. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings. In adults with diabetes, elevated AISI levels are strongly associated with an increased risk of mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The sustained increase in diabetes prevalence represents a significant challenge to global public health1. According to International Diabetes Federation (IDF) projections, approximately 783 million adults aged 20–79 years worldwide will have diabetes by 20452. Cardiovascular disease remains the predominant cause of mortality in diabetic patients3. Improved management of cardiovascular risk factors has revealed malignant neoplasms as an increasingly important contributor to mortality in this population4. Early identification of risk factors is critical for developing targeted interventions to reduce mortality in diabetic patients.

Chronic low-grade inflammation contributes significantly to diabetes pathogenesis, disease progression, and mortality risk5. The Aggregate Index of Systemic Inflammation (AISI) establishes a novel approach for assessing systemic inflammation through algorithmic integration of multiple hematological parameters. This composite metric demonstrates stronger clinical predictive performance than conventional single-parameter markers6,7. AISI shows clinically meaningful associations with disease progression in hypertension6 and pulmonary fibrosis8. Furthermore, AISI has demonstrated prognostic value for mortality risk in multiple cancers, including prostate9, esophageal10, and gastric11, establishing its potential as a clinically useful inflammatory marker. However, evidence regarding the association between AISI and mortality in diabetic populations remains limited. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to investigate the relationship between AISI and mortality risk from both cardio-cerebrovascular disease (CCD) and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

This study utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a cross-sectional survey conducted nationwide by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in the United States12. Demographic, socioeconomic, dietary, and health-related data were collected using questionnaires, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. These assessments include anthropometric measurements and laboratory assessments. The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approved all NHANES protocols, and all participants provided written informed consent. As this study analyzed de-identified, publicly available NHANES data, additional institutional review board approval was not required. All NHANES data and documentation are publicly available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx).

We analyzed data from nine consecutive NHANES cycles (2001–2018) to ensure adequate sample size and representativeness. The merged dataset incorporated demographic data, questionnaire responses, laboratory test results, and anthropometric measurements. The detailed process for variable selection and handling is provided in Supplementary Table S1. We included participants aged ≥ 20 years who met any of the following diagnostic criteria for diabetes13,14:

-

1.

Self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes;

-

2.

Current use of antidiabetic medications or insulin therapy;

-

3.

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level ≥ 6.5%;

-

4.

Fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L;

-

5.

2-h glucose (OGTT) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L.

The exclusion criteria were as follows.

-

1.

Pregnant women;

-

2.

Participants lacking survival data;

-

3.

Individuals without available peripheral blood lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, or platelets.

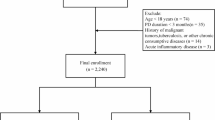

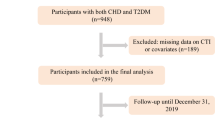

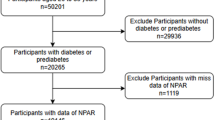

This study ultimately enrolled 8333 participants. The detailed screening process is depicted in Figure 1.

Outcome variables

Mortality status and cause of death were ascertained through linkage with the National Death Index (NDI) records up to December 31, 2019, using standardized protocols established by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)15. Detailed linkage methodology and documentation are publicly available through the NCHS (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality.htm).

The primary outcomes were mortality from cardio-cerebrovascular diseases and malignant neoplasms. The codes for CCD mortality in the NCHS 2019 Public Use-Related Mortality File Codebook are 001 and 005. The code for malignant neoplasm mortality is 002. The NHANES database employs unique identifiers (SEQN) to match participant data with NDI death records, adhering to CDC-established data linkage protocols. The follow-up duration for each participant was determined from the date of their NHANES baseline interview until the date of death or the end of follow-up on December 31, 2019.

Independent variables

The NHANES Laboratory Technologists Procedures Manual (LPM) outlines the protocols for blood sample collection and processing. Complete blood count (CBC) was determined using the Coulter® method for cell counting and sizing and an automated device for sample mixing and dilution. CBC analyses were conducted on all blood samples by using a Beckman Coulter MAXM instrument. The AISI was calculated using the formula16:

Covariates

Standardized questionnaires administered during household interviews were used to collect data on age, sex, race, educational level, marital status, family income-to-poverty ratio, smoking status, medical conditions, and medication use. The questionnaires were administered by trained medical personnel. Races were categorized as Mexican American, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or other. Educational level was classified into three categories: less than high school, high school or equivalent, and college or higher. Marital status was categorized as partnered or unpartnered. Smoking status was divided into two categories: never smoker and smoker. Alcohol status was categorized into two categories: never drinker and drinker. The family income-to-poverty ratio was categorized into three ranges: ≤ 1.0, 1.0 < PIR ≤ 3.0, and > 3.0. Medical examinations and subsequent laboratory assessments were conducted at the mobile examination center to obtain anthropometric measurements and biochemical variables. Body mass index (BMI) was determined by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared and categorized as ≤ 25.0 kg/m2, 25.0 < BMI ≤ 30.0 kg/m2, and > 30.0 kg/m2.

Missing value management

Researchers initially excluded variable with over 10% missing data, including those related to systolic and diastolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and insulin levels. Multiple imputation methods were used to estimate other missing values (The percentage of imputed data is detailed in Supplementary Table S2). The random forest algorithm, implemented in the “mice” package of R software and trained on available variables, was used for multiple imputations.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Non-normally distributed variables are summarized as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). Group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA for normally distributed variables and Kruskal–Wallis tests for non-normal distributions. To determine the predictive value of the AISI for outcomes (CCD mortality and malignant neoplasm mortality), a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was employed. To control for potential confounding factors, three models were developed, Model 1 as the unadjusted model; Model 2 included adjustments for age, sex, and race; Model 3 included adjustments for age, sex, race, family income-to-poverty ratio, uric acid, albumin, smoking status, red blood cell count, insulin use, oral hypoglycemic agent use, diabetes duration, HbA1c, and AST. Furthermore, an RCS curve was used to explore the relationship between AISI and mortality risk, adjusting for confounding factors. Kaplan–Meier survival curves (stratified by AISI quartiles) were compared using log-rank tests. Subgroup analyses were conducted to assess whether the effect of AISI on mortality risk differed across subgroups, including age, sex, education, family income-to-poverty ratio, alcohol consumption, BMI, comorbid hypertension, glycosylated hemoglobin levels, and cardiovascular disease. Heterogeneity across subgroups was assessed using the Cochran’s Q test. We performed four sensitivity analyses to assess robustness. First, we excluded participants who died within the first two years of follow-up to mitigate potential reverse causality. Second, multiple imputation was conducted for variate with missing values. Then, the relationship between AISI and mortality was validated in the 10 imputed complete datasets. Third, we conducted additional sensitivity analyses were conducted adjusting for CKD, chronic bronchitis, and rheumatoid arthritis to account for potential confounding by these conditions. Finally, AISI was categorized into tertiles to further confirm the relationship between AISI tertiles and mortality. All analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.2; R Foundation). Statistical significance was defined as two-tailed p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

The analysis included 8,333 patients with diabetes, of whom approximately 51.3% were males. During a mean follow-up period of 90.2 ± 54.5 months, there were 718 deaths from CCD and 388 from malignant neoplasms. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics stratified by AISI quartiles (Q1: ≤ 169.77, Q2: 169.77 < AISI ≤ 266.80, Q3: 266.80 < AISI ≤ 414.10, Q4: > 414.10). Over half (54.9%) of the cohort were obese, defined as having a BMI of 30 or above. Patients with higher AISI levels exhibited showed white blood cell, monocyte, and platelet counts, alongside reduced lymphocyte counts. Additionally, higher AISI levels were associated with higher proportions of men, non-Hispanic whites, unmarried individuals, smokers, as well as greater prevalence of CKD, arthritis, and chronic bronchitis. Furthermore, diabetes duration was longer among individuals with higher AISI levels. Mortality rates from CCD and malignant neoplasms strongly increased with higher AISI levels.

Association of AISI with CCD mortality and malignant neoplasm mortality in diabetes

The Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed a strong association between AISI and CCD mortality; specifically, per 1-SD increase in AISI, the HR was 1.29 (5% CI 1.21 –1.37). A similar association was observed for malignant neoplasm mortality, with an HR of 1.31 (95% CI 1.20–1.42). After adjusting for potential confounders such as age, sex, race, family income-to-poverty ratio, serum albumin, uric acid, AST, red blood cell count, insulin use, use of oral hypoglycemic agents, diabetes duration, HbA1c, and smoking status, these dose-dependent associations remained robust, with HRs of 1.18 (95% CI 1.11–1.26) for CCD mortality and 1.20 (95% CI 1.10–1.30) for malignant neoplasm mortality. When AISI was categorized into quartiles, exhibited strong associations with mortality compared to Q1 group in the unadjusted model: CCD mortality (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.49–2.25) and malignant neoplasm mortality (HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.49–2.66). Even after comprehensive adjustments, the Q4 group maintained associations with mortality risks: CCD mortality (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.22–1.86) and malignant neoplasm mortality (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.27–2.29). These results indicate that AISI is positively associated with CCD and malignant neoplasm mortality in patients with diabetes. Table 2 provides a detailed overview of the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis results.

RCS analysis and survival analysis

RCS analysis indicated that mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients increased with higher AISI values (Fig. 2). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were utilized to assess the association between AISI quartiles and mortality outcomes for CCD and malignant neoplasms. Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed differences in mortality between the Q4 group and the Q1 group, as shown by the log-rank test (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

RCS curve of AISI with CCD mortality (A) and malignant neoplasm mortality (B) in diabetic patients. Adjusted for age, gender, race, poverty income ratio, serum albumin, smoking status, serum uric acid, red blood cell count, insulin user, oral hypoglycemic agent use, diabetes duration, HBA1C, and AST. The solid and red shadow represents the estimated values and their 95% CIs, respectively. Linear relationships were observed in all Figures.

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated clinically relevant survival differences between Q4 group and Q1 group.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup and interaction analyses were performed across variables including gender, marital status, education, family income-to-poverty ratio, age (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years), smoking status, alcohol status, arthritis, chronic bronchitis, and CKD. The stratified results were consistent with the overall findings; in all subgroups, AISI was consistently associated with mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasm in patients with diabetes (Fig. 4). There was no significant interaction between the AISI and the stratified variables. Additionally, heterogeneity tests indicated low heterogeneity across most subgroups (Supplementary Table S6).

Sensitivity analysis

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, excluding participants who died within the first two years of follow-up did not alter the results, addressing potential protopathic bias (Supplementary Table S3). Second, Cox regression analyses using AISI tertile groups remained consistent, further validating our findings (Supplementary Table S5). Third, multiple imputations with 10 datasets confirmed that the association between AISI and mortality was robust to missing data (Supplementary Fig. 1). Finally, additional adjustments for CKD, chronic bronchitis, and rheumatoid arthritis in sensitivity analyses did not change the observed associations (Supplementary Table S4). Collectively, these analyses confirm the reliability and validity of our results across different scenarios.

Discussion

Our study evaluated the relationship between AISI and mortality due to CCD and malignant neoplasms in patients with diabetes. The principal findings were as follows: (1) AISI was strongly associated with an increased risk of mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients, even after adjusting for potential confounders. The Cox regression results showed that a 1-SD increase in AISI was associated with a 29% increase in the risk of CCD mortality (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.21–1.37) and a 31% increase in the risk of malignant neoplasm mortality (HR 1.31, 95% CI 1.20–1.42). (2) The RCS curve indicated a positive correlation between AISI and mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms. The risk of mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms increased with higher AISI values, and stratified and sensitivity analyses in diabetic patients confirmed the consistency and robustness of this association.

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most prevalent and rapidly growing diseases globally, with cardiovascular disease identified as the leading cause of death in patients with diabetes 17. Studies have demonstrated that malignant tumors represent a significant cause of mortality among diabetic patients, along with cardiovascular disease, and diabetes has been shown to elevate the risk of specific cancers,including pancreatic, liver, breast, colorectal, urinary, and gynecological tumors18,19,20. Furthermore, malignant neoplasms mortality risk increases with elevated glucose levels21. Current research concludes that chronic low-grade inflammation is associated not only with the development of diabetes but also with a poor prognosis22.

Chronic low-grade inflammation in patients with diabetes may contribute to atherosclerosis, thereby increasing the risk of death from CCD23,24,25. Extensive evidence consistently supports these findings, showing that elevated monocyte and neutrophil counts and reduced lymphocyte levels are positively associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease26,27,28,29. A systematic meta-analysis evaluating hematological variables in patients with diabetes and healthy controls demonstrated that patients with diabetes had significantly higher monocyte, relative neutrophil, and basophil counts. Conversely, the relative lymphocyte count decreased30.

Current evidence suggests that chronic inflammation is closely linked to all stages of tumorigenesis, including proliferation, infiltration, metastasis, and apoptosis31. Studies have also indicated that a heightened inflammatory state is typically associated with a poorer prognosis in patients with cancer32. A high proportion of peripheral lymphocytes before treatment has been reported as an independent favorable prognostic factor for various tumors33. Additionally, lymphocytes are involved in tumor infiltration and play a crucial role in the tumor immune environment34,35.

Chronic low-grade inflammation is associated with the development and adverse outcomes of many chronic diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and cancer36. Inflammatory biomarkers are widely used to guide the diagnosis and prognosis of diseases. For instance, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have been extensively studied in relation to diabetes37. Elevated levels of hs-CRP, NLR, or PLR are associated with increased mortality in diabetic patients38,39. Studies have shown that in patients with T2DM, NLR is an inflammatory marker more closely related to the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than hs-CRP37. It is speculated that hs-CRP is more strongly associated with acute inflammatory responses. In contrast, NLR may better indicate chronic inflammatory states relevant to CVD risk. Compared with these established markers, the AISI is a novel composite index that integrates three white blood cell subtypes plus platelets. This unique combination allows AISI to comprehensively assess systemic inflammation and reflect the interplay between thrombocytosis, inflammation, and immunity in more comprehensively than markers like hs-CRP or NLR. Therefore, AISI may serve as a powerful and reliable indicator of inflammatory status. Zinellu et al. found that AISI predicted four-year survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) more effectively than other inflammatory indices such as NLR and PLR40. Huang et al. also demonstrated that AISI had better accuracy in identifying CKD and low eGFR compared to lymphocyte count and PLR41. These findings further support the potential clinical application of AISI. Studies have shown that AISI is associated with the occurrence of IPF8, COVID-1942, certain cancers9,10, hypertension6, and rheumatoid arthritis7. AISI can also predict adverse outcomes. Fan et al. found that AISI is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)43. Additionally, AISI has been shown to predict mortality in patients with coronavirus disease44, as well as survival and progression-free survival in cancer patients11,45. Elevated AISI levels have been identified as an independent predictor of all-cause mortality46. However, it is important to note that while AISI offers a more comprehensive assessment of systemic inflammation, it also has limitations. Unlike well-established markers with extensive clinical validation, AISI is a newer index and may require further validation in diverse patient populations.

Our research demonstrates a positive correlation between AISI and CCD mortality, as well as malignant neoplasm mortality in diabetic patients. The findings indicate that a 1-SD increase in AISI is associated with a 29% increase in the risk of CCD mortality and a 31% increase in the risk of malignant neoplasm mortality. These findings underscore the clinical significance of AISI as a marker of systemic inflammation and its potential utility in identifying patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes. Incorporating AISI measurement into routine clinical practice aid in risk stratification and identification of high-risk populations. Furthermore, it assists clinicians in devising personalized treatment strategies. For instance, when selecting hypoglycemic medications for patients with elevated AISI, priority should be given to those with anti-inflammatory properties, such as SGLT-247 and GLP-148,49, as these medications can both lower blood glucose levels and potentially reduce adverse outcomes50, further prospective studies are needed to confirm these recommendations before widespread clinical application. In our study, Beginning from the Q2 group (AISI range: 169.77–266.80), we observed elevated mortality risks for both malignant neoplasms and CCD compared to the Q1 group. This threshold range for Q2 group aligns with previous research. For example, Huang et al. found that AISI is graded associated with the prevalence of CKD when the index exceeds 181.2741. Additionally, Su et al. revealed a non-linear relationship between AISI and T2DM, with a notable inflection point at an AISI value of 21016. In clinical practice, routine measurement of AISI in patients with diabetes could be clinically useful for risk stratification and timely intervention to prevent adverse outcomes.

The potential mechanisms underlying the positive correlation between AISI and mortality have not been fully elucidated. The following are some of the possible mechanisms. AISI levels increase in diabetic patients due to chronic low-grade inflammation, thereby increasing mortality risk. Neutrophils play a critical role in the inflammatory response associated with atherosclerosis51,52. They cause endothelial cell damage and tissue ischemia by releasing various inflammatory mediators, chemotactic agents, and reactive oxygen species53. Monocytes can infiltrate tissues, differentiate into macrophages, and participate in immune defense and repair processes54,55. Platelet activation also plays a key role in atherosclerotic thrombosis in diabetes56. Patients with impaired glucose metabolism exhibit increased platelet activation and TX synthesis, as demonstrated in previous studies56. Consequently, platelets may induce metabolic disturbances and subsequent vascular damage in diabetic patients57. In contrast, lymphocytes play a regulatory role in inflammation and may exert an inhibitory effect on atherosclerosis58.

In the context of cancer, neutrophils are highly active innate immune cells with tumor-promoting properties59,60,61. They facilitate cancer progression by stimulating angiogenesis, inducing immunosuppression, and enhancing metastasis62. Neutrophils also create an inflammatory microenvironment that supports cancer cell proliferation and spread through the release of cytokines and growth factors63,64. Platelets are closely associated with malignant tumor progression, metastasis, immune evasion, and chemotherapy resistance65. They can adhere to tumor cells, forming microaggregates that protect cancer cells from immune surveillance. Platelets also assist in the adhesion of cancer cells to the endothelium and their subsequent dissemination to distant organs. High platelet counts in cancer patients may indicate a higher metastatic potential. Lymphocytes are crucial for cancer immunity, and a high pre-treatment peripheral lymphocyte percentage is an independent favorable prognostic factor for various tumors66. Thus, elevated platelet counts may reflect higher metastatic potential, while lymphocytes represent one of the most critical effector mechanisms in cancer immunity.

This study had several strengths. First, it utilized a large, nationally representative sample to establish a plausible association between AISI and mortality in diabetic patients. Second, numerous potential confounders were controlled through multivariate-adjusted Cox regression analysis, stratified analysis, and interaction analysis, thereby reducing bias and enhancing the reliability of our findings.

However, this study has limitations. Firstly, as an observational study, a causal relationship between AISI and mortality could not be established despite the large sample size; this should be further explored in future research with larger cohorts. Secondly, although various methods were employed to minimize bias, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Therefore, large randomized controlled trials are necessary to validate these findings. Thirdly, our sample was drawn from a U.S. database, which may limit the generalizability of our results to other populations or ethnic groups. We suggest that future studies aim to replicate our analysis in diverse populations to assess the robustness of our findings across different ethnic groups and geographical regions.

Conclusion

AISI is a valuable marker for evaluating inflammation in diabetic patients. Our research shows that higher AISI levels are strongly linked to greater mortality risk from CCD and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients. Thus, AISI could serve as a useful prognostic tool in diabetes management. However, more randomized clinical trials are needed to confirm these results.

Data availability

Data availability: Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Khunti, K. et al. Diabetes and multiple long-term conditions: A review of our current global health challenge. Diabetes Care 46, 2092–2101. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci23-0035 (2023).

Hossain, M. J., Al-Mamun, M. & Islam, M. R. Diabetes mellitus, the fastest growing global public health concern: Early detection should be focused. Health Sci. Rep. 7, e2004. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.2004 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. The combined effects of arteriosclerosis and diabetes on cardiovascular disease risk. Intern. Emerg. Med. 19, 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-023-03478-3 (2024).

Pearson-Stuttard, J. et al. Trends in predominant causes of death in individuals with and without diabetes in England from 2001 to 2018: An epidemiological analysis of linked primary care records. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 9, 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(20)30431-9 (2021).

Weinberg Sibony, R., Segev, O., Dor, S. & Raz, I. Overview of oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetes. J. Diabetes 16, e70014. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.70014 (2024).

Xiu, J. et al. The aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI): A novel predictor for hypertension. Front Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1163900. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1163900 (2023).

Yin, X., Zou, J. & Yang, J. The association between the aggregate index of systemic inflammation and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: Retrospective analysis of NHANES 1999–2018. Front Med. 11, 1446160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1446160 (2024).

Zinellu, A. et al. Blood cell count derived inflammation indexes in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung 198, 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-020-00386-7 (2020).

Xie, W. et al. A novel Nomogram combined the aggregate index of systemic inflammation and PIRADS score to predict the risk of clinically significant prostate cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2023, 9936087. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9936087 (2023).

Wang, H. K. et al. Clinical usefulness of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and aggregate index of systemic inflammation in patients with Esophageal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer Cell Int. 23, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-023-02856-3 (2023).

Feier, C. V. I. et al. An exploratory assessment of pre-treatment inflammatory profiles in gastric cancer patients. Diseases https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12040078 (2024).

Akinbami, L. J. et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2017-March 2020 prepandemic file: Sample design, estimation, and analytic guidelines. In Vital and health statistics. Ser. 1, Programs and Collection Procedures 1–36 (2022).

Zhang, Q., Xiao, S., Jiao, X. & Shen, Y. The triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: Evidence from NHANES 2001–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 279. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02030-z (2023).

Xu, F., Earp, J. E., Adami, A., Weidauer, L. & Greene, G. W. The relationship of physical activity and dietary quality and diabetes prevalence in US adults: Findings from NHANES 2011–2018. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163324 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Body roundness index and all-cause mortality among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2415051. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051 (2024).

Su, Z. et al. Obesity indicators mediate the association between the aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Lipids Health Dis. 24, 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-025-02589-4 (2025).

Strain, W. D. & Paldánius, P. M. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 17, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0703-2 (2018).

Vigneri, P., Frasca, F., Sciacca, L., Pandini, G. & Vigneri, R. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 16, 1103–1123. https://doi.org/10.1677/erc-09-0087 (2009).

Nicolucci, A. Epidemiological aspects of neoplasms in diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 47, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-010-0187-3 (2010).

Herrigel, D. J. & Moss, R. A. Diabetes mellitus as a novel risk factor for gastrointestinal malignancies. Postgrad. Med. 126, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2014.10.2825 (2014).

Ling, S. et al. Association of type 2 diabetes with cancer: A meta-analysis with bias analysis for unmeasured confounding in 151 cohorts comprising 32 million people. Diabetes Care 43, 2313–2322. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-0204 (2020).

Pellegrini, V. et al. Inflammatory trajectory of type 2 diabetes: Novel opportunities for early and late treatment. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13191662 (2024).

Keeter, W. C., Moriarty, A. K. & Galkina, E. V. Role of neutrophils in type 2 diabetes and associated atherosclerosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 141, 106098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2021.106098 (2021).

Lontchi-Yimagou, E., Sobngwi, E., Matsha, T. E. & Kengne, A. P. Diabetes mellitus and inflammation. Curr. Diab. Rep. 13, 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-013-0375-y (2013).

Poznyak, A. et al. The diabetes mellitus-atherosclerosis connection: The role of lipid and glucose metabolism and chronic inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21051835 (2020).

Ye, Z. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index as a potential biomarker of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 933913. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.933913 (2022).

Kong, F. et al. System inflammation response index: A novel inflammatory indicator to predict all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in the obese population. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 15, 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01178-8 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Dynamic status of SII and SIRI alters the risk of cardiovascular diseases: Evidence from Kailuan cohort study. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 5945–5957. https://doi.org/10.2147/jir.S378309 (2022).

Chen, X., Li, A. & Ma, Q. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and systemic immune-inflammation index as predictors of cardiovascular risk and mortality in prediabetes and diabetes: A population-based study. Inflammopharmacology 32, 3213–3227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-024-01559-z (2024).

Bambo, G. M. et al. Changes in selected hematological parameters in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med. 11, 1294290. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1294290 (2024).

Elinav, E. et al. Inflammation-induced cancer: Crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 759–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3611 (2013).

Greten, F. R. & Grivennikov, S. I. Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 51, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025 (2019).

Iseki, Y. et al. The impact of the preoperative peripheral lymphocyte count and lymphocyte percentage in patients with colorectal cancer. Surg. Today 47, 743–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-016-1433-2 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. The prognostic and biology of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy of cancer. Br. J. Cancer 129, 1041–1049. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-023-02321-y (2023).

Bai, Z. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer: The fundamental indication and application on immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 12, 808964. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.808964 (2021).

Minihane, A. M. et al. Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: current research evidence and its translation. Br. J. Nutr. 114, 999–1012. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114515002093 (2015).

Hoes, L. L. F. et al. Relationship of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, in addition to C-reactive protein, with cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 213, 111727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111727 (2024).

Parrinello, C. M. et al. Six-year change in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Am. Heart J. 170, 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.017 (2015).

Liu, W. Y. et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio: A novel prognostic factor for prediction of 90-day outcomes in critically ill patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Medicine 95, e2596. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000002596 (2016).

Zinellu, A. et al. The aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI): A novel prognostic biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184134 (2021).

Huang, D. & Wu, H. Association between the aggregate index of systemic inflammation and CKD: Evidence from NHANES 1999–2018. Front Med. 12, 1506575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1506575 (2025).

Zinellu, A., Paliogiannis, P. & Mangoni, A. A. Aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI), disease severity, and mortality in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144584 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. The prognostic value of hematologic inflammatory markers in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 28, 10760296221146184. https://doi.org/10.1177/10760296221146183 (2022).

Nooh, H. A. et al. The role of inflammatory indices in the outcome of COVID-19 cancer patients. Med. Oncol. 39, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-021-01605-8 (2021).

Shen, X. et al. Evaluation of peripheral blood inflammation indexes as prognostic markers for colorectal cancer metastasis. Sci. Rep. 14, 20489. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68150-y (2024).

Bai, X. et al. The aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality in congestive heart failure patients: Results from NHANES 1999–2018. Sci. Rep. 15, 18282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01196-8 (2025).

Bendotti, G. et al. The anti-inflammatory and immunological properties of SGLT-2 inhibitors. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 46, 2445–2452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-023-02162-9 (2023).

Bendotti, G. et al. The anti-inflammatory and immunological properties of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Pharmacol. Res. 182, 106320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106320 (2022).

Alharbi, S. H. Anti-inflammatory role of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and its clinical implications. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 15, 20420188231222370. https://doi.org/10.1177/20420188231222367 (2024).

Mehdi, S. F. et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1: A multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent. Front Immunol. 14, 1148209. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1148209 (2023).

Zhang, X., Kang, Z., Yin, D. & Gao, J. Role of neutrophils in different stages of atherosclerosis. Innate Immun. 29, 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/17534259231189195 (2023).

Hartwig, H., Silvestre Roig, C., Daemen, M., Lutgens, E. & Soehnlein, O. Neutrophils in atherosclerosis. A brief overview. Hamostaseologie 35, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.5482/hamo-14-09-0040 (2015).

Luo, J., Thomassen, J. Q., Nordestgaard, B. G., Tybjærg-Hansen, A. & Frikke-Schmidt, R. Neutrophil counts and cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 44, 4953–4964. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad649 (2023).

Jaipersad, A. S., Lip, G. Y., Silverman, S. & Shantsila, E. The role of monocytes in angiogenesis and atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.019 (2014).

Libby, P. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Vascul. Pharmacol. 154, 107255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vph.2023.107255 (2024).

Beckman, J. A., Creager, M. A. & Libby, P. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. JAMA 287, 2570–2581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.19.2570 (2002).

El Haouari, M. Platelet oxidative stress and its relationship with cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Curr. Med. Chem. 26, 4145–4165. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867324666171005114456 (2019).

Mehu, M., Narasimhulu, C. A. & Singla, D. K. Inflammatory cells in atherosclerosis. Antioxidants https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11020233 (2022).

Wu, L., Saxena, S. & Singh, R. K. Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1224, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35723-8_1 (2020).

Giese, M. A., Hind, L. E. & Huttenlocher, A. Neutrophil plasticity in the tumor microenvironment. Blood 133, 2159–2167. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-11-844548 (2019).

Zheng, Z., Xu, Y., Shi, Y. & Shao, C. Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment and their functional modulation by mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Immunol. 379, 104576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2022.104576 (2022).

Jablonska, J., Rist, M., Lang, S. & Brandau, S. Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment-foes or friends?. HNO 68, 891–898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-020-00928-8 (2020).

Li, M. O. et al. Innate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 39, 725–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2021.05.016 (2021).

Que, H., Fu, Q., Lan, T., Tian, X. & Wei, X. Tumor-associated neutrophils and neutrophil-targeted cancer therapies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1877, 188762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188762 (2022).

Roweth, H. G. & Battinelli, E. M. Lessons to learn from tumor-educated platelets. Blood 137, 3174–3180. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019003976 (2021).

Shanta, K. et al. Prognostic value of peripheral blood lymphocyte telomere length in gynecologic malignant tumors. Cancers https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12061469 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund (82060337),the Shenzhen City Science and Technology Plan Project Basic Research Surface Project (JCYJ20220531092412028, JCYJ20230807121306012), the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region(2025MS08169), the Inner Mongolia Public Hospital research joint fund Science and Technology Project (2024GLLH0605) and the Baotou City Health Science and Technology Project (wsjkkj2022057).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Hongwei Zhu, Guo Shao. Formal analysis: Hongwei Zhu, Zhihui Li, Peng Wang and Hua Li. Investigation: Wei Xie and Guo Shao. Methodology: Hongwei Zhu, Zhihui Li, Peng Wang and Hua Li. Software: Zhihui Li and Peng Wang. Supervision: Hongwei Zhu and Zhihui Li. Validation: Zhihui Li, Hua Li and Peng Wang. Resources: Hongwei Zhu and Guo Shao. Funding Acquisition: Hongwei Zhu, Guo Shao. Writing—original draft preparation: Hongwei Zhu and Wei Xie. Writing—review and editing: Zhihui Li, Hua Li, Peng Wang, Hongwei Zhu and Guo Shao. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

Studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHNES). The patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

li, Z., Li, H., Wang, P. et al. Relationship between aggregate index of systemic inflammation and mortality from CCD and malignant neoplasms in diabetic patients. Sci Rep 15, 26545 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12094-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12094-4