Abstract

This article focused on the coking characteristics of aromatic oils derived from coal tar. The study examines fresh and degraded lighter oils with a density up to 1045 kg/m³ and a naphthalene content below 7%, as well as heavier oils with a density above 1055 kg/m³ and a naphthalene content exceeding 10%. The coke residue yield was assessed and the component composition was determined via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Results showed that light oil exhibited a higher tendency to form coke compared to heavy oil. Oxidation products formed during oil operation within a concentration range of 0.1–0.3%, with a higher concentration of these products observed in light oil. Thermogravimetric analysis confirms that light oil residue degrades in a more controlled manner, resulting in higher coking ability due to rapid decomposition and favorable coke precursor kinetics. In contrast, heavy oil undergoes slower, more complex decomposition, forming denser, more graphitic coke. FTIR confirms that light oil has higher coking ability due to its aliphatic content and reactive groups (C = O, OH), with a 9.0% C = O peak at 1771–1772 cm⁻¹ absent in heavy oil. In contrast, heavy oil forms denser coke with lower yield due to its stable aromatic nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coking ability of oils is an essential parameter in industrial applications, particularly in refining and petrochemical processes. Understanding the thermal and catalytic behavior of different oils is essential for optimizing production efficiency, minimizing undesirable byproducts, and reducing the environmental footprint of industrial operations. Coal tar oils, which are complex mixtures rich in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)1,2, exhibit distinct coking behaviors that significantly influence processes such as distillation and thermal cracking3,4. These behaviors are critical in determining the operational efficiency and longevity of industrial equipment, as well as the quality of the final products.

Coal tar wash oil, widely used as an absorbent for benzene hydrocarbons in coke oven gas, undergoes repeated heating and cooling cycles during its operational life. These thermal cycles adversely affect its properties, particularly viscosity, density5,6, and coke residue yield. The coking ability of coal tar wash oil is a key indicator of oxidation and polymerization processes, which are influenced by factors such as the presence of corrosion products7, resins, sulfur-containing compounds, and salts introduced via coke oven gas aerosols (e.g., sulfates) or formed through oxidation (e.g., thiocyanates, thiosulfates)8. The coking tendency is further exacerbated by the presence of aromatic hydrocarbons, with the thermal stability of individual components following the order: acenaphthene > α-methylnaphthalene > β-methylnaphthalene > fluorene > phenanthrene > diphenyl > naphthalene9.

Coke formation, the process by which solid carbon residues are generated from hydrocarbon compounds, plays a dual role in industrial applications. While it is advantageous in processes such as petroleum coke production10, it is detrimental when coke deposits form on catalysts or reactor surfaces, leading to reduced equipment efficiency11. Coke formation is also a critical factor in the combustion of petroleum fuels12 and the performance of motor oils13. The mechanism of coke formation is complex and influenced by the nature of the oil, heating conditions, and the presence of catalysts14. Under slow heating, selective breakdown of weaker bonds (e.g., unsaturated compounds, methyl groups) occurs, whereas accelerated heating leads to random bond breakage, including stronger bonds, due to material overheating.

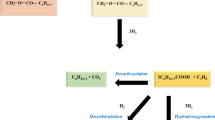

Aromatic hydrocarbons with alkyl substituents undergo reactions such as dealkylation, dehydrogenation, and condensation, which contribute to coke formation. In oxidizing environments, low-temperature oxidation processes produce oxygen-containing compounds15,16 that initiate polymerization17. Recent studies have explored coke formation from coal tar fractions, primarily focusing on pyrolysis conditions typical of coke chambers18. These studies have shown that coke yield is temperature-dependent, with significant increases observed above 500 °C. Anthracene and wash oil fractions exhibit the highest coke yields, correlating with their high concentrations of three- and four-ring aromatic hydrocarbons. Phenol content in wash oil remains stable up to 550 °C, with only slight decreases at higher temperatures, a behavior also observed in naphthalene and anthracene oil fractions.

Despite these advancements, significant research gaps remain. While the thermal stability and coking behavior of coal tar-derived oils have been studied, the influence of impurities from coke oven gas, particularly fog tar, on the coking behavior of different oil types has not been systematically investigated. Furthermore, the extent to which polymer formation and other factors affect coking behavior across various oil types remains poorly understood. This study addresses these gaps by comparing the coking ability of light (imported) and heavy (domestic) oils, with a focus on identifying the factors that contribute to the observed differences in coking behavior. The findings provide valuable insights into optimizing industrial processes and improving the quality of petroleum-derived products.

While previous studies have explored the thermal stability and coking behavior of coal tar-derived oils, there is a lack of comprehensive understanding regarding the influence of coke oven gas impurities, particularly fog tar, on the coking behavior of different oil types. Additionally, the role of polymer formation and other factors in coking behavior across various oil types has not been systematically investigated. This study aims to address these gaps by comparing the coking ability of light (imported) and heavy (domestic) oils, providing new insights into the factors driving coking behavior and its implications for industrial applications.

Research objectives

The primary objective of this study was to investigate and compare the propensity for coke formation between two main types of wash oils: (1) lighter oils, characterized by a density of up to 1045 kg/m³ and a naphthalene content of less than 7%, and (2) heavier oils, with a density above 1055 kg/m³ and a naphthalene content exceeding 10%. Addressing this issue holds significant practical importance, particularly in the context of selecting an optimal absorbent that requires minimal replenishment during operation. This is especially critical given the current oil shortages in Ukraine, where efficient resource utilization is paramount. Furthermore, this study aims to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of oil thickening and coke formation, which are influenced by factors such as polymerization, oxidation, and the presence of aromatic hydrocarbons. By providing a deeper understanding of these processes, the findings will contribute to the development of improved methods for controlling polymerization and optimizing the operational properties of wash oils in industrial applications.

Materials and methods

Characteristic of wash oil

Wash oils from two benzene recovery plants were selected for this study. One plant was charged with a relatively “light” oil from an imported supplier following a complete replacement and thorough cleaning of the existing equipment. After three months of operation, samples of fresh oil, operating oil, and spent polymers were collected for analysis. The second benzene recovery unit used fresh oil produced in-house from coal tar, and corresponding samples were collected for the study. The operating conditions and performance parameters of the two units were generally comparable.

The quality indicators of the oils were evaluated in accordance with the standards outlined in the normative document19. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 1.

Coke residue yield

The coke residue yield was evaluated using a standardized method for the quality control of coal oils. The coke yield was determined by eliminating volatile components from a sample of the analyzed product in a closed porcelain crucible (outer diameter 35 mm, lid inner diameter 38 mm), heated at 850 ± 10 °C for 10 min. The mass of the resulting coke residue was then measured following the guidelines20. The limits of total relative measurement error are ± 20% with a confidence probability of P = 0.95; the normative control values for convergence and reproducibility are 0.2% and 0.3%, respectively.

In the context of this study, the coking yield was used to evaluate the potential of wash oils to form coke, which can lead to operational issues such as the blockage of furnace tubes. Thus, the coking yield value provides a valuable tool to compare and select wash oils with minimal coking tendencies, helping to mitigate such problems.

To assess the coking tendency of the wash oils, 6% coal tar was added. This concentration was experimentally identified as the threshold at which a significant increase in the coke residue (coking number) was observed, indicating the onset of reactive condensation processes and establishing it as the minimum effective concentration for wash oil polymerization. The coke residue yield was determined as described in8. Narrow fractions were also isolated from the spent working oil (spent polymers after oil regeneration) and tested for coking propensity using the same methodology. To obtain reliable data, the coke residue yields are averaged from at least five closely related determinations.

Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

The component composition of the oil was determined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. To identify the substances within the mixture, sample aliquots were prepared by dissolving the weighed samples in an organic solvent, specifically dichloromethane, and then chromatographed. The chemical analysis of the samples was performed using an Agilent 7890 A GC System coupled with a 5975 C Inert mass-selective detector. The separation of mixture components was achieved using a HP-5MS (5% diphenyl) capillary column (30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm). The method provides measurements of the components in wash oil with a relative total measurement error of ± δ, not exceeding 25% at a confidence level of P = 0.95 for the entire range of measurements.

The data were obtained by analyzing the Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC) outputs generated through Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. The relative abundances of the components were determined by integrating the specific peaks corresponding to the identified compounds and calculating their areas as a percentage of the total peak area. These peaks were matched with the NIST 08 electronic library to ensure accurate identification. The GC-MS method specifications, including the conditions for peak integration and library matching, are provided in Table 2.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

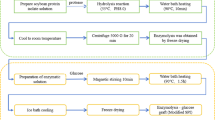

Coke formation from the non-boiling residue of working oils was investigated using a Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA701, Leco Corporation, St. Joseph, Missouri, USA). Solid oil residue was obtained by evaporation in open air and subsequently ground to achieve a homogeneous state. Programmed heating was conducted up to the temperature at which coke formation was complete (900 °C). The experiment was performed under the following conditions: an inert nitrogen atmosphere was maintained throughout the heating program using a flow rate of approximately 3.0 L/min; heating rate of 10 °C/min; a total heating duration of 1 h and 19 min.

A commonly used approach to describe the kinetics of solid-state reactions, including decomposition, pyrolysis, and other thermal processes, is the reaction-order model:

where α represents the extent of conversion, and n is the reaction order. The rate equation for this model is given by21:

where: k is the reaction rate constant and t is time. The rate constant k follows the Arrhenius equation, which, in logarithmic form, is expressed as:

where: k is the reaction rate constant, A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature (Kelvin)22.

The reaction rate constant k was obtained by fitting experimental TGA data to the reaction-order model (1), where the derivative dα/dt was calculated numerically from the α vs. time curve. The temperature-dependent values of k were then used to construct an Arrhenius plot for determination of the activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (A).

Infrared spectroscopic analysis

IR spectroscopy was used to analyze both fresh and operational oil samples. To prepare solid samples from the waste oil, the oil was distilled in a glass flask until a solid, non-volatile residue was obtained. The IR spectra of the samples were recorded in the range of 4000 cm⁻¹ to 400 cm⁻¹, with a resolution of 1 cm⁻¹, using a Shimadzu FTIR-8400 S spectrometer. Spectrum processing was performed using IR Solutions software.

X-ray fluorescence analysis

The identification and quantification of sulfur and metal concentrations in the distillate residues of spent oils were carried out using an ElvaX ProSpector 2 X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Ukraine). The device analyzes elements ranging from Mg (Z = 12) to U (Z = 92) utilizing an X-ray tube with a W-anode (maximum voltage: 40 kV, maximum current: 100 µA) and a thermoelectrically cooled PIN-diode detector (active area: 6 mm², energy resolution: <180 eV at 5.9 keV).

Results and discussion

Molecular composition and coking behaviour of the was oils

The provided data (Table 1) indicate that fresh oils can be categorized into ‘light’ oils, characterized by lower density, higher distillate content below 285°C, and reduced naphthalene content, and relatively ‘heavy’ oils. During operation, an increase in density is observed, along with the saturation of the oil with naphthalene, a reduction in the content of methyl homologs of naphthalene, and a decrease in the most valuable fraction of the oil, which distils below 270 °C. These degradation processes of wash oil during operation are also reflected in changes to the oil’s component composition. Figure 1 presents the distribution of components based on molecular weight, as determined by GC-MS analysis.

Figure 1 illustrates the key changes in the component composition, highlighting an overall increase in the average molecular weight. This shift is marked by a decrease in methylnaphthalenes and a rise in the concentrations of dibenzofuran, fluorene, anthracene, and phenanthrene. Additionally, there is an accumulation of indene and naphthalene from coke oven gas in the operating oil.

As follows from mass-spectrometry data, light oil absorbs much more unsaturated hydrocarbons (indene and styrene) and naphthalene during operation. This is due to the narrower boil-off interval of the oil, as the naphthalene content in fresh ‘light’ oil is 6.8% (Table 1). Therefore, concentrations of indene (MW = 116 Da) and naphthalene (MW = 128 Da) in fresh oil are below the equilibrium values obtained at saturation of operating oil with naphthalene- and indene-containing coke gas.

Mass spectrometry data also showed that oxidation products of the oil components, including 1-Acenaphthenone, 1-Phenylethan-1-one, 2,2-Dimethyl-1-acenaphthenone, 1-(3-Methylphenyl)ethan-1-one, were absent in the fresh oils and were also detected in the operating oil within a concentration range of 0.1–0.3%.

Table 3 presents data on determination of coking behaviour of samples of fresh and operational oil, as well as fractions of used oil including those with additive initiating coking (coal tar).

Estimating coke residue yield of operating oils for two installations it should be noted that they are high enough and close enough in values, according to our observations, the range of change of these values for different installations of Ukraine is 3 ÷ 18%. Values of coke yields of fresh oils are typical for the majority of fresh oils supplied for replenishment of benzene units23.

The coke residue yield for the light oil indicates a relatively higher coking tendency compared to the heavy oil. The light wash oil contains more reactive components across all temperature fractions. These include lighter aromatic compounds in the lower fractions and larger PAHs in the higher fractions, both of which contribute to increased coke formation. This is reflected in consistently higher coke residue yield values across the temperature ranges, especially in the 270–310 °C fraction.

The heavy wash oil, although denser, appears to be composed of more stable hydrocarbons that do not readily form coke. This is particularly evident in the 270–310 °C fraction, where despite having more high-boiling components, its coke yield remains low. This indicates that the heavy oil is less prone to the polymerization and cracking reactions that lead to coke.

Coal tar components with boiling points above 360 °C were introduced into the oil. These high-boiling fractions typically produce 28–45% coke residue under high-temperature coking conditions24.

According to our data, the maximum observed increase in the coke residue yield when testing fresh oils of different production with the addition of coal tar was + 2.8%.

The results also showed that the narrow fraction 250–270 °C shows the lowest tendency to coke formation, and the fractions less than 250 °C and more than 270 °C show the highest tendency.

The experimental data suggest that the light oil’s reactivity increases significantly when coal tar is added (as indicated by the higher coke yields), while the heavy oil shows limited synergistic behavior. This could be because the light oil contains more reactive PAHs that interact with the coal tar, leading to greater coke formation. Table 4 shows the data on the content of highly reactive compounds in the investigated oils obtained by GC-MS method.

As can be seen from the above data in ‘light’ fresh and operational oil the content of unsaturated aromatic hydrocarbons and hydrocarbons containing functional groups is higher than in ‘heavy’ oils, which gives ‘light’ oils increased reactivity.

The reactivity of the listed components is due to the presence of groups such as hydroxyl (-OH), alkyl (-CH₃), isopropenyl group (-CH = CCH₃) and vinyl (-CH = CH₂), which activate the ring in electrophilic substitution reactions. Electron-donating groups make the ring more nucleophilic and increase its reactivity in reactions such as Friedel-Crafts alkylation or other electrophilic aromatic substitutions.

Ethenylbenzene, 1 H-Indene, 1-Methyl-1 H-indene, 2-Methyl-1 H-indene, 2,3-Dihydro-1 H-inden-1-one, 3-(Naphthalen-2-yl)prop-2-enal, 1-Acenaphthylenone, 1-(Phenylmethylidene)-1 H-indene – play unique roles as dienophiles or dienes in Diels-Alder-type reactions, which are not characteristic of most coal wash oil compounds.

Substances such as 2,3-Dihydro-1 H-inden-1-one, 1-Acenaphthylenone, 2,2-Dimethylacenaphthen-1-one can undergo condensation polymerization via their carbonyl groups and participate in aldol condensation. Oxidation can convert the carbonyl group into a carboxylic acid or cause more extensive ring cleavage, depending on the oxidation conditions.

Indene has the highest concentration in operating oil. Indene can act as a dienophile in Diels–Alder reactions and undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution due to its aromatic structure. Figure 2 shows the scheme of such interaction with the formation of a higher molecular complex structure.

Compounds with double and triple bonds, nitriles (C ≡ N), xanthogenates (C ≡ S), azo compounds (-N = N-), ketones and quinones (C = O), which are highly reactive, are known to be identified in coal tar25. Such components are easily involved in copolymerisation and condensation reactions with high boiling coal tar components. Due to this the coking ability of oils increases, this phenomenon is similar to the addition of highly reactive plasticiser additives to coal tar pitch also to improve the coking ability26.

Thus, the thermal instability of wash light oil and its fractions is explained by the fact that the light oil contains more reactive PAHs that interact with the coal tar, leading to greater coke formation.

Adding coal tar does not lead to a proportional increase in coke yield. Coal tar as it is known includes oil fractions with boiling range < 180–360 °C, and non-boiling residue – pitch, in which the precursors of coking – multi-ring PAHs are concentrated. Therefore, the introduction of wash oil into the tar dilutes the multi-ring coke precursors and can both enhance and weaken the coking process, depending on the oil composition and process conditions. Oils can act as solvents, reducing the concentration of active hydrocarbons and thus reducing coke formation. On the other hand, oils containing reactive hydrocarbons and longer alkyl chains can promote coke formation through destructive polymerisation processes.

Based on the above theoretical justifications of coke formation processes in oils it can be noted that in order to reduce these processes it is necessary to maintain an optimal temperature regime to minimise excessive cracking and polymerisation; to reduce the concentration of aromatic hydrocarbons in the feedstock; to eliminate catalysts prone to coke formation.

Determination of the coke residue yield of fresh wash oil when a coke-initiating additive is introduced can be the basis for predicting the behaviour of the oil in the working cycle. To obtain informative data, the coking ability of different oils should be compared with the addition of coal tar of the same quality.

Kinetics of the decomposition of wash oil residues

Residues from distillation of operating oils were powdered and analysed by thermogravimetric method. The mass loss curves for the solid residues of light and heavy oils are presented in Fig. 3.

Thermogravimetric analysis determined the coke yield from the distillation residue to be 48.8% for the light oil and 45.5% for the heavy oil. Light oil decomposes more rapidly at lower temperatures, yielding more coke due to polymerizable aromatics or resin-like compounds. A sharp peak in the DTA curve of light oil around 400 °C indicates rapid mass loss, attributed to the thermal decomposition of lighter and more volatile components in the residue. The secondary shoulder observed on the curve corresponds to a temporary mass increase, suggesting that the residual material underwent secondary reactions such as gas-phase incorporation, cross-linking, or polymerization, rather than simple volatilization or decomposition of an additional component. In contrast, heavy oil decomposes gradually at higher temperatures, indicating the presence of more thermally stable aromatic compounds, which contribute to reduced coke formation.

Light oil residue likely contains reactive bicyclic aromatics (e.g., indene, coumarone), which readily polymerize at moderate temperatures, forming coke even though they have lower initial thermal stability. In comparison, heavy oil, with a higher proportion of tricyclic aromatics, undergoes more gradual thermal degradation, producing smaller molecular fragments and exhibiting a lower tendency toward solid-phase polymerization.

The reaction order was determined by analyzing the kinetic equations corresponding to different orders. The quality of the linear fit was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2), which quantifies the goodness of fit and reflects the agreement between the observed data and the theoretical model.

To determine the most appropriate kinetic model for each thermal decomposition stage, experimental mass loss data were fitted to reaction-order models of first (n = 1), second (n = 2), and selected non-integer orders (n, fitted numerically). The goodness of fit for each model was quantified using the coefficient of determination (R²). Higher R² values indicate better conformity between the experimental data and the kinetic model.

Table 5 summarizes the fitting results for three temperature ranges (Stages 1–3), corresponding to distinct phases in the thermal behavior of light and heavy wash oils. For each stage, R² values are provided for fixed reaction orders (n = 1 and n = 2), as well as for the order n that gave the best fit, along with its corresponding R² value.

The reactions of oil vaporization follow a zeroth-order kinetic model for both light and heavy oil, as indicated by the best-fitting order (n = 0). However, in solid-state reactions a pure zero-order process is uncommon, as these reactions often depend on the available reactive surface or diffusion constraints and the reaction rate is controlled by a factor other than the remaining reactant concentration, such as a constant heat flux or a uniform decomposition mechanism.

The second stage represents the primary decomposition of hydrocarbons, including cracking reactions. Light oil follows a third-order kinetic model, indicating a complex reaction mechanism. Heavy oil exhibits a mixed behavior, where second-order kinetics (n = 2) also provide a good fit (R² = 0.95), but the best fit corresponds to a fractional order (n = 0.77, R² = 0.98), suggesting variations in molecular weight distribution and reactivity.

On the final coking phase, both light and heavy oils follow a third-order reaction mechanism (n = 3). However, light oil maintains a higher R² value (0.96), while heavy oil exhibits a lower fit (0.78), indicating a more complex decomposition pathway with less uniform behavior.

This analysis confirms that light oil residue follows a more controlled and predictable degradation pathway, whereas heavy oil exhibits a wider distribution of reaction mechanisms due to its higher molecular weight and aromatic content. This aligns with the fact that heavy oil contains more high-molecular-weight fractions, leading to more complex reactions.

Table 6 presents the kinetic parameters of the Arrhenius equation determined for different stages of coking in the investigated oil samples.

The activation energy values obtained for the first and second stages of the process are consistent with those reported for petroleum oils analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis in an inert atmosphere (13–53 kJ/mol)27.

During the initial volatile release stage, light oil has a significantly higher pre-exponential factor than heavy oil, indicating a faster rate of volatile loss. Additionally, the activation energy of light oil is higher, suggesting that the decomposition of initial volatiles requires more energy.

In the main decomposition and coke precursor formation stage, light oil follows third-order kinetics (n = 3), while heavy oil follows a fractional order (n = 0.77), indicating a more complex and gradual decomposition process in heavy oil. Light oil also exhibits higher values of both the pre-exponential factor and activation energy, pointing to a much more rapid reaction rate. This suggests that its decomposition involves breaking stronger chemical bonds, likely within aromatic and polycyclic structures.

During the final coking stage, the pre-exponential factor (A) for light oil is higher than that for heavy oil, suggesting a faster coke formation rate. Light oil also has a higher activation energy (Ea), implying that coke formation occurs through more energy-intensive pathways, likely involving polyaromatic growth and cross-linking.

Overall, light oil exhibits a higher coking ability due to its rapid decomposition, higher activation energy, and more favorable kinetics for coke precursor formation. In contrast, heavy oil decomposes more gradually due to a lower apparent activation energy barrier, resulting in a slower coking process. The resulting residue, based on visual inspection, appeared denser and more cohesive, suggesting the formation of a more structurally ordered, graphitic-type coke.

Evolution of chemical functionalities in the wash oils

Table 7 presents the results of IR spectroscopy of samples of fresh and operational oils, as well as residues from distillation of operational oils.

To evaluate the degree of aromaticity of the studied samples, the following index was used28:

where D3030 represents the optical density of the 3030 cm− 1 band, which characterizes the presence of aromatic structures, and D2910 represents the optical density of the 2910 cm− 1 band, which characterizes aliphatic C–H valence vibrations.

As expected, the heavy oil has a higher aromaticity index (η = 1.7) compared to the light oil (η = 1.2). During the process, the light oil becomes enriched with naphthalene, resulting in an increase in its aromaticity index to η = 1.4. Interestingly, the viscous residue (pitch) obtained from the stripping (regeneration) process exhibits lower aromaticity values for both oils compared to the fresh oils. This suggests that polymerization processes involving branched aromatic derivatives dominate over the condensation processes of aromatics.

In the 3418–3434 cm− 1 region, a significant increase in absorbance is observed in the residues (0.98% for light oil and 0.9% for heavy oil), suggesting the formation of hydroxyl-containing species during operation, likely due to oxidation and polymerization reactions. Hydroxyl groups are commonly associated with polar compounds, which can contribute to coking through hydrogen bonding and subsequent condensation reactions29.

In the 1771–1772 cm− 1 range, the light fresh oil shows a prominent C = O peak (9.0%) that is absent in the heavy oil. The drastic reduction or complete disappearance of these peaks in operating oils and residues indicates the transformation of carbonyls into larger structures. Carbonyl-containing compounds, such as aldehydes and ketones, are highly reactive intermediates involved in coking and condensation reactions30.

For light oil, the higher initial aliphatic content and more pronounced changes in hydroxyl and carbonyl groups indicate that it undergoes more significant condensation and polymerization reactions, resulting in a higher coke yield.

For heavy oil, the greater aromatic stability and the presence of pre-formed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) contribute to slower condensation but lead to the formation of a denser coke residue.

FTIR results confirm that light oil exhibits a higher coking ability due to its higher aliphatic content, the presence of reactive functional groups (C = O, OH), and significant transformations during operation. In contrast, heavy oil produces a denser but lower coke yield, attributed to its stable aromatic nature and lower content of reactive aliphatic components.

X-ray fluorescence assessment of sulfur and metal levels in operating oils

Assessment of the differences in sulphur and metal content that accumulate in the working oil during operation was performed using the X-ray fluorescence method. The results are presented in Table 8.

As the obtained data show, the compared oil samples contain approximately equal amounts of iron, silicon, and aluminium. This indicates that corrosion products and coal particles carried over from the coke oven did not influence the polymerisation of the oil. The higher sulphur content in light oil suggests the influence of hydrogen sulphide on coke formation processes. Moreover, it indicates a higher absorption capacity of light oil for hydrogen sulphide.

Conclusion

This study aimed to compare the behavior of light and heavy wash oils during operation, with a focus on their reactivity, stability, and coking tendencies. The analysis revealed that light oil possesses a higher content of unsaturated and functionalized aromatic hydrocarbons, making it more chemically reactive than heavy oil. This increased reactivity is reflected in its higher affinity for contaminants such as indene and naphthalene, which equilibrate during operation with the coke oven gas stream.

During operation, light oil accumulates more oxidation products (0.1–0.3%), which, along with its elevated content of polymerizable aromatics, explains its greater tendency to undergo structural degradation and coke formation. The thermogravimetric analysis showed that light oil decomposes more rapidly and at lower temperatures, following third-order kinetics with a higher activation energy. These conditions favor faster but more energy-intensive coke formation, often involving resin-like intermediates.

In contrast, heavy oil is characterized by a higher content of thermally stable tricyclic aromatics and a lower concentration of reactive aliphatic compounds. It decomposes more gradually at elevated temperatures, with fractional-order kinetics and lower activation energy, forming a denser but smaller quantity of coke.

When coal tar was introduced as a coking initiator, it was found that the 250–270 °C fraction exhibited the lowest coke yield, while fractions below 250 °C and above 270 °C were more reactive and prone to polymerization and coke formation. This confirms that coking behavior is fraction-dependent and closely linked to the molecular structure of the oil components.

Overall, the greater coking tendency of light oil is attributed to its chemical composition, faster degradation kinetics, and stronger interaction with coal tar, whereas heavy oil, although more stable, produces denser coke due to its gradual and more ordered breakdown.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GC-MS:

-

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- MW:

-

Molecular weight

- PAHs:

-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- P:

-

Confidence probability

- FTIR:

-

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

- TGA:

-

Thermogravimetric Analysis

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

- A:

-

Pre-exponential factor

- Ea:

-

Activation energy

References

Jihao, C. et al. Study on lightening of coal Tar with metal oxide supported γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Sci. Rep. 13, 18366 (2023).

Bannikov, L. P. et al. Evaluation of demulsifiers efficiency for coal Tar dehydration according to the value of its viscosity reduction. Him Fiz. Technol. Poverhni. 14 (1), 102–112 (2023).

Eagan, N. M. et al. Chemistries and processes for the conversion of ethanol into middle-distillate fuels. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 223–249 (2019).

Peng, Y. et al. Diamondoids and thiadiamondoids generated from hydrothermal pyrolysis of crude oil and TSR experiments. Sci. Rep. 12, 196–201 (2022).

Bannikov, L. P. & Miroshnichenko, D. V. Adjustment and interpretation of coefficients for coal Tar viscosity/temperature equations. Pet. Coal. 65 (1), 173–182 (2023).

Bannikov, L. et al. Coke quenching plenum equipment corrosion and its dependents on the quality of the biochemically treated water of the coke-chemical production. Chem. Chem. Technol. 16 (2), 328–336 (2022).

Bannikov, L. P., Miroshnichenko, D. V. & Bannikov, A. L. Evaluation of the effect of resin forming components on the quality of wash oil for benzene recovery from coke oven gas. Pet. Coal. 65 (2), 387–399 (2023).

Bannikov, A. L. & Karnozhytskyi, P. V. Quality control of absorbent oil for capturing benzene hydrocarbons by coke residue yield. Journ Coal Chem. 3, 27–31 (2023).

Kovalev, Y. T. Nauchnyye osnovy i tekhnologiya pererabotki vysokokipyashchikh fraktsiy kamennougol’noy smoly s polucheniyem politsiklicheskikh uglevodorodov (Kontrast, 2001).

Santos, A. R. et al. Analysis of petroleum coke consumption in some industrial sectors. JPSR 3 (1), 1–7 (2015).

Guisnet, M. & Magnoux, P. Organic chemistry of coke formation. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 212 (1–2), 83–96 (2001).

Liu, D. et al. Coke yield prediction model for pyrolysis and oxidation processes of low-asphaltene heavy oil. ENERG. FUEL. 6, 1–59 (2019).

Cheng, Y. et al. Oxidative and pyrolytic coking characteristics of supercritical-pressure n-decane and its influence mechanism on heat transfer. Fuel 362, 130874–130878 (2024).

Kok, M. V. et al. Thermal characterization of crude oils in the presence of limestone matrix by TGA-DTG-FTIR. J. Pet. Eng. 154, 495–501 (2017).

Pu, W. et al. Comparison of different kinetic models for heavy oil oxidation characteristic evaluation. ENERG. FUEL. 31 (11), 12665–12676 (2017).

Chen, Z. et al. High-pressure air injection for improved oil recovery: low-temperature oxidation models and thermal effect. ENERG. FUEL. 27 (2), 780–786 (2013).

Khansari, Z. et al. Low-temperature oxidation of Lloydminster heavy oil: kinetic study and product sequence Estimation. Fuel 115, 534–538 (2014).

Jin, X. et al. Insights into coke formation during thermal reaction of six different distillates from the same coal Tar. FPT 211, 10659–10669 (2021).

TU U 20. 1-00190443-117:2017. Coal Oil Absorbent51 (SE ‘UKHIN’, 2017).

TU U 20.1-00190443-123:2017. Coke-chemical Feedstock for the Production of Carbon Black42 (SE ‘UKHIN’, 2017).

Vyazovkin, S. et al. ICTAC kinetics committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim Acta. 520 (1–2), 1–19 (2011).

Zhao, Y. et al. A thermal characteristics study of typical industrial oil based on thermogravimetric-differential scanning calorimetry (TG-DSC). Fire. 7, 401–420 (2024).

Miroshnichenko, D. et al. Composition and polymerisation products influence on the viscosity of coal Tar wash oil. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 27322–27336 (2024).

Smagulova, N. T. et al. Coke Prod. Coal Tar Fractions Coke Chem 65, 531–534 (2022).

Ma, Z. H. et al. Value-added utilization of high-temperature coal tar: A review. Fuel 292, 119954 (2021).

Kovalev, E., Cheshko, F. & Ponomarenko, N. The use of Coke-Chemical materials to the regulation of the electrode coal Tar pitch quality. Pet. Coal. 63 (2), 317–323 (2021).

Murugan, P. et al. Pyrolysis and combustion kinetics of Fosterton oil using thermogravimetric analysis. Fuel 88, 1708–1713 (2009).

Shin, S. M., Park, J. K. & Jung, S. M. Changes of aromatic CH and aliphatic CH in In-situ FT-IR spectra of bituminous coals in the thermoplastic range. ISIJ Int. 55 (8), 1591–1598 (2015).

Gunka, V. et al. Chemical modification of road oil bitumens by formaldehyde. Pet. Coal. 62, 420–429 (2020).

Patty, D. J. & Lokollo, R. R. FTIR spectrum interpretation of lubricants with treatment of variation mileage. APTA 52, 13–20 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M. was involved in conceptualization, methodology and editing. L.B. took part in performing the experiments and writing. O.B. took part in methodology. E.R. took part in investigation and result interpretation. V. T. was involved in contribution of reagents, materials, analysis tools and data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

The author consents to participate.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miroshnichenko, D., Bannikov, L., Borisenko, O. et al. Kinetic analysis and comparison of the coking behavior of coal Tar oil. Sci Rep 15, 34042 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12119-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12119-y