Abstract

Persea americana (avocado) is widely recognized for its nutritional and therapeutic value; however, its leaves, abundant and often discarded, remain underexplored. With growing interest in plant-derived bioactives, comprehensive phytochemical profiling of avocado leaves is essential to validate their pharmacological and nutraceutical potential. Fresh leaves of P. americana collected in Uganda were shade-dried and extracted by cold maceration using ethanol and ethyl acetate. Phytochemical characterization was conducted using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) to identify functional groups and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to detect bioactive constituents. Extraction conditions and analytical parameters were optimized for reproducibility. FT-IR spectra revealed functional groups characteristic of phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and esters, including hydroxyl (–OH), carbonyl (C=O), alkenes (C=C), aromatic (C–H), methylene (C–H₂), methyl (C–H₃), and esters (C–O). GC-MS showed distinct solvent-dependent profiles: the ethanolic extract (PA-ETH) contained major compounds such as 13-Octadecenal (35.90%), Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester (10.50%), and linoleic acid ethyl ester (7.02%), noted for antioxidant and cardioprotective properties. The ethyl acetate extract (PA-ETHYL) exhibited higher compound diversity, including 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- (1.12%), 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl-, (Z,E)- (12.31%), and Caryophyllene oxide (1.48%), linked to anti-inflammatory, Hypocholesterolemic, and anticancer activities. Notably, some compounds with no previously reported pharmacological activity may represent novel bioactives. Solvent polarity significantly influenced phytochemical composition, with ethanol favoring polar antioxidants and ethyl acetate enhancing extraction of non-polar bioactives. This study highlights the therapeutic promise of P. americana leaves and establishes a robust chemical foundation for future bioactivity-guided isolation, pharmacological validation, and natural product drug discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persea americana (avocado) is globally valued for its nutritional and therapeutic properties and is known by various names across cultures, such as, Mparachichi (Swahili), Ovakedo (Uganda), Maluma (South Africa), Paya (Twi), Pia (Yoruba), Avocatier or Zaboka (French), and Pagua (Spanish)1. While the fruit is widely consumed for its rich content of healthy fats, vitamins, and antioxidants2,3, increasing scientific attention is now turning to the pharmacological potential of its non-edible parts, particularly the leaves. In traditional medicine systems across Africa and Latin America, avocado leaves have long been used to manage ailments such as diabetes, hypertension, and inflammatory disorders4,5,6. Despite their ethnomedicinal relevance and environmental abundance, the leaves are often discarded as agricultural waste and remain underutilized in scientific research relative to the fruit.

Avocado leaves are widely available, non-commercialized, and typically discarded, making them a sustainable and low-cost resource for therapeutic exploration, particularly in low-resource settings. They are known to contain a diverse spectrum of phytochemicals, including flavonoids, polyphenols, terpenoids, and fatty acid derivatives, which have been linked to antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic effects1. Understanding their composition through phytochemical profiling is therefore crucial for both validating traditional claims and identifying potential drug leads.

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy are established tools in natural product chemistry. GC-MS provides detailed resolution of volatile and semi-volatile compounds7,8, while FT-IR enables rapid identification of functional groups characteristic of bioactive phytochemical classes such as phenolics, alkaloids, and glycosides9,10. Used in combination, these techniques offer a comprehensive approach to plant compound characterization.

Although previous studies have used GC-MS to investigate P. americana leaf extracts11,12,13,14, few have examined the comparative influence of solvent polarity on extractable constituents. Moreover, no published work has systematically compared ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of P. americana leaves using an integrated GC-MS and FT-IR approach. These two solvents differ markedly in polarity, which directly impacts the type and quantity of phytochemicals recovered. Furthermore, the phytochemical profile of P. americana leaves grown in Uganda, a country with diverse agroecological zones, remains underexplored and may yield distinct chemotypic signatures.

The aim of this study is to characterize and compare the phytochemical content of ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of avocado (P. americana) leaves collected from Uganda using both FT-IR and GC-MS. By linking functional groups and compound identities to known pharmacological effects, this work seeks to assess how solvent polarity influences phytochemical extraction, identify compounds of potential therapeutic relevance, and provide foundational data to guide future bioactivity studies, including antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory screening.

This research addresses a current gap in phytochemical profiling literature and emphasizes the value of underutilized plant parts as a sustainable resource for natural product drug discovery.

Materials and methodology

Collection, identification, and preparation of plant specimens

Fresh leaves of Persea americana (avocado) were collected from the botanical premises of Kampala International University (KIU), Ishaka, Uganda. The plant was taxonomically identified and authenticated by Dr. Eunice of the Biology Department, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, and a voucher specimen (ID: AOM-2024-001) was deposited for reference.

The leaves were rinsed with distilled water to remove surface dust and contaminants, and then shade-dried in a well-ventilated space at ambient temperature for 14 days to preserve heat-sensitive phytochemicals and minimize microbial contamination. The dried material was pulverized using a high-speed electric blender and sieved to a fine powder for uniform extraction efficiency.

Extraction methods (cold maceration)

Two solvents of varying polarity, ethanol (polar) and ethyl acetate (semi-polar), were used to extract phytoconstituents to evaluate solvent-specific extraction efficiency.

Sample preparation

The finely blended powdered avocado leaves were weighed using an analytical balance, and the reading was recorded at equilibrium.

Exactly 600 g of powdered avocado leaves was separately soaked in 3000 mL of ethanol or ethyl acetate (1:5 w/v) in sterile glass containers. The mixtures were kept at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 72 h with occasional shaking/stirring every 6–12 h to facilitate solute diffusion.

Filtration and concentration

After maceration (72 h), the extracts were filtered through double-layered muslin cloth followed by Whatman No. 1 filter paper to remove residual plant debris.

The combined filtrates (ethanol and ethyl acetate) were concentrated at lower pressure using a rotary evaporator at temperatures below the solvent boiling points (ethanol: 40 °C; ethyl acetate: 35 °C) to prevent thermal degradation. Final drying was performed using a vacuum oven at 40 °C. Extract yields were calculated as; 49.72 g (8.29% yield) for Ethanolic extract and 32.38 g (5.40% yield) for Ethyl acetate extract.

The concentrated crude extracts were stored in sealed amber bottles at 4 °C for further analysis.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis

GC-MS principle

The model of the instrument used for the analysis is Agilent technologies 7890 GC system and the model of the detector is Agilent technologies 5975 MSD (Mass Spect. Detector). The principle behind the GC analysis is separation techniques. In separation techniques, there are two phases-the mobile and the stationary phase. The mobile phase is the carrier gas (Helium, 99.99% purity), while the stationary phase is the column. The model of the column is HP5 MS with length 30 m, internal diameter 0.320 mm, while the thickness is 0.25 µm. The oven temperature program is initial temperature of 80 °C to hold for 1 min. It increases by 10° per minute to the final temperature of 240 °C to hold for 6 min. The injection volume is 1 µl and the heater or detector temperature is 250 °C.

Operation: The sample extracted was put in a vial bottle and the vial bottle was placed in auto injector sample compartment. The automatic injector injects the sample into the liner. The mobile phase pushes the sample from the liner into the column where separation takes place into different components at different retention time. The MS interpret the spectrum MZ (mass to charge ratio) with molar mass and structures.

Compound identification

The extract’s bioactive compounds were identified by analyzing their retention times on an HP-5MS column using gas chromatography (GC) and by comparing their mass spectra with the NIST 14 library installed in the MassHunter software (Agilent Technologies), with a match threshold of ≥ 80%.

FTIR spectroscopy procedure

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) analysis was performed using a Buck Scientific M530 spectrophotometer (USA) equipped with a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector and a potassium bromide (KBr) beam splitter, as described by Dike et al.15. A 1.0 g portion of the extract was homogenized with 0.5 mL of Nujol and mounted onto a salt pellet for transmission analysis using the KBr pellet method. Spectra were recorded in the range of 4000 to 600 cm⁻1 with a resolution of 4 cm⁻1 and 32 co-added scans. Spectral data were processed using the Gramme A1 software and interpreted in transmittance mode15,16.

The analysis focused primarily on the functional group region (4000–1000 cm⁻1), which includes distinct absorption bands characteristic of major phytochemical groups such as flavonoids, polyphenols, glycosides, and terpenoids. Although peaks below 1000 cm⁻1 (fingerprint region) were not emphasized due to spectral complexity and overlap, future comparative studies incorporating spectral libraries may improve compound specificity in this region.

Results

Extract yield

Table 1 illustrates the percentage yield, calculated using the formula; Yield (%) = (Mass of Extract Obtained/Mass of Plant Material Used) × 100, based on an initial plant material weight of 600 g. Under the same extraction conditions, the ethanolic extract yielded 8.29%, while the ethyl acetate extract yielded 5.40%.

Given: Mass of extract obtained = 49.72 g, Mass of plant material used = 600 g

Given: Mass of extract obtained = 32.38 g.

Mass of plant material used = 600 g

Tables 2 and 3 below presents the list of phytochemical constituents identified in the extracts of ethanol and ethyl acetate of avocado leaves through Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, with each compound’s molecular formula, molecular weight, and retention time (RT) given.

A comparative analysis of the major phytochemicals in the ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts is provided in Table 4, with the presence or absence of key compounds noted, offering insights into the solvent-dependent extraction of bioactive metabolites.

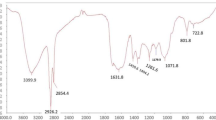

Table 5 summarizes the functional groups detected in the ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of avocado leaves using FT-IR spectroscopy. The distinctive absorption peaks and their corresponding functional groups are listed, indicating the presence of various bioactive compounds.

Table 6 summarizes the comparative interpretation of FT-IR spectral bands in ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of Persea americana leaves. The wavenumbers, assigned functional groups, and inferred phytochemical classes indicate the presence of diverse bioactive constituents including flavonoids, terpenoids, fatty acids, esters, and polyphenols in both extracts, with certain spectral differences attributed to solvent polarity.

Figure 1 (Related Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 and Supplementary Figures S1–S6) and Fig. 8 (Related Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 and Supplementary Figures S7–S31) show the GC-MS chromatogram and identified bioactive compounds in the ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of avocado (Persea americana) leaves. The x-axis displays the retention time (RT) in minutes, while the y-axis represents the relative abundance of the detected compounds. Each peak corresponds to a distinct phytochemical compound, with variations in peak height reflecting the relative concentration of each component. The chromatographic profile illustrates the diversity of bioactive compounds present in the extract, which were subsequently identified based on their retention times using an HP-5MS capillary column and matched against the NIST 14 spectral library in MassHunter software (Agilent Technologies) with a match threshold of ≥ 80%. “Expanded visual data and experimental outputs not included in the main text are available in Supplementary Figs. S1–S31.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 1 in the ethanol extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 2.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 2 in the ethanol extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 2.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 3 in the ethanol extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 2.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 4 in the ethanol extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 2.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 5 in the ethanol extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 2.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 6 in the ethanol extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 2. Additional data supporting peaks 7–12 in the ethanolic extract of Persea americana leaves are provided in Supplementary Figs. S1–S6. The corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 2.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 1 in the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 3.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 2 in the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 3.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 3 in the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 3.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 4 in the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 3.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 5 in the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 3.

Representative mass spectrum and library identification for Peak 6 in the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves. Corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 3. Additional data supporting peaks 7–31 in the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves are provided in Supplementary Fig. S7–S31. The corresponding compound identities are presented in Table 3.

The FT-IR spectrum of the extracts of ethanol and ethyl acetate Persea americana (avocado) leaves is shown in Figs. 15 and 16. It displays characteristic absorption peaks corresponding to various functional groups present in the extract. The x-axis represents the wavenumber (cm⁻1), while the y-axis indicates transmittance (%). Prominent peaks observed in the spectrum suggest the presence of functional groups such as hydroxyl (−OH), carbonyl (C=O), alkene (C=C), and aromatic compounds, which are indicative of phytochemical constituents including flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, and phenolic compounds.

Discussion

This study investigated the phytochemical composition of Persea americana (avocado) leaves using FT-IR and GC-MS, focusing on the influence of two solvents, ethanol and ethyl acetate, on extractable bioactive compounds. While the ethanolic extract had a higher extraction yield (8.29%) than the ethyl acetate extract (5.40%), GC-MS analysis revealed a greater number and diversity of compounds in the ethyl acetate extract (31 peaks) compared to (12 peaks) in the ethanolic extract. This underscores that extraction yield alone does not directly equate to phytochemical richness and highlights the importance of solvent polarity and analytical sensitivity in natural product research.

GC-MS is well-recognized for its sensitivity and precision in profiling volatile and semi-volatile phytochemicals, offering reliable compound identification through spectral matching and retention data7,8. In this study, the ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts shared several major functional groups, such as hydroxyl (−OH), carbonyl (C=O), and aromatic (C=C), alkenes (C=C), methylene (C–H₂), methyl (C–H₃), and esters (C–O) as revealed by FT-IR spectroscopy, a distinct absence of C–H stretching vibrations in the ethanolic extract indicated a lower abundance of aliphatic hydrocarbon chains. This suggests a subtle variation in lipophilic content between the two extracts. In contrast, GC-MS analysis showed more pronounced qualitative differences in compound profiles; although a few compounds, such as caryophyllene and 13-Octadecenal, were present in both extracts, the majority of identified constituents were unique to each solvent. This divergence highlights the differential solubility of volatile and semi-volatile phytochemicals depending on solvent polarity, even when the overall functional group landscape appears similar1,53,54.

GC-MS profiling of ethanolic extract of Persea americana leaves (PA-ETH) identified key constituents such as 13-Octadecenal (Z) (35.9%), which has reported antimicrobial, antibacterial, and antioxidant activity.55,56,57, and Phytol (2.32%), a diterpene alcohol known for its anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects29,30,31. Additional compounds, linoleic acid ethyl ester, hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, and 5, 8-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester, are known for lipid-lowering, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antibacterial effects25,26,27,28,58,59,60,61,62. Notably, 13-Oxabicyclo [10.1.0] tridecane (10.69%) was present in substantial quantity but lacks reported pharmacological activity, suggesting its novelty or underexploration in phytomedicine.

In contrast, the ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves (PA-ETHYL) showed a broader spectrum of bioactive compounds. These included 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl-, (Z,E) (12.31%), Hexadecane (1.14%), 13-Tetradece-11-yn-1-ol (3.23%), and Z,Z-5,16-Octadecadien-1-ol acetate (3.59%), which have reported antimicrobial, antifungal, Hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, and sedative activities21,34,38,41,46,52. Eicosane (0.96%), also found in this extract, has demonstrated anticancer and analgesic properties as reported by Tiloke et al. and Okechukwu63,64. Additionally, several compounds detected in the ethyl acetate extract, such as Succinic acid, tridec-2-yn-1-yl ester (1.43%), 3-Eicosyne (1.54%), 1,8,11-Heptadecatriene, (Z,Z) (1.12%), 2-Nonadecanone, O-methyloxime (15.76%), 2-Tridecanone, O-methyloxime (2.95%), 1,5-Heptadiene, 2,6-dimethyl- (1.06%), Cyclopentane, 1-isobutylidene-3-methyl- (4.50%), 1,4-Hexadiene, 3,3,5-trimethyl- (4.54%), 7-Tetradecyne (1.12%), and E-2-Methyl-3-tetradecen-1-ol acetate (1.49%), currently lack documented pharmacological functions. These findings highlight a pool of underexplored constituents with potential therapeutic value that warrant further investigation.

Notably, caryophyllene was detected in both extracts, whereas its oxidized derivative, caryophyllene oxide, was exclusive to the ethyl acetate extract. Both compounds are well documented for their potent anti-inflammatory effects, primarily mediated via CB₂ receptor activation, as reported by Bagher et al. and Klauke et al.65,66. In addition, they exhibit anticancer and neuroprotective activities, supported by findings from Dougnon (2021) and Alghareeb et al.67,68. Similarly, 9, 12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z) (3.66%), identified in the ethyl acetate extract, has been associated with anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective62,69,70.

When compared with previous phytochemical studies on P. americana leaves from various geographical regions, such as Brazil (Lima et al.)11, Turkey (Uysal et al.)12, Egypt (Abd Elkader et al., Mahmoud et al.)13,53, Cameroon (Njateng et al.)14, and Nigeria (Oboh et al.)71, our findings reveal notable consistencies and distinctions. Several compounds detected in our study including, linoleic acid derivatives, and phytol, have also been reported in these studies, suggesting a shared core phytochemical profile across regions. Furthermore, FT-IR analysis confirmed overlapping functional groups such as hydroxyl (−OH), carbonyl (C=O), and aromatic (C=C), which are commonly associated with phenolics, flavonoids, and terpenoids as documented in earlier works.

However, variations in compound abundance and chemical diversity suggest that Uganda’s unique agroecological conditions may influence plant metabolite profiles. This regional variation highlights the importance of localized phytochemical profiling in validating ethnopharmacological uses and informing plant-based drug discovery.

These findings also reinforce that solvent polarity plays a critical role in shaping the phytochemical landscape of P. americana leaf extracts, with ethanol favoring antioxidant-rich compounds, and ethyl acetate yielding greater chemical diversity with broader bioactive potential.

FT-IR and GC-MS integration

FT-IR spectra supported the presence of phenolic and flavonoid-like compounds through bands corresponding to hydroxyl (−OH), carbonyl (C=O), alkene (C=C), and ester (C–O) functional groups. However, many flavonoids and phenolic acids are non-volatile and thermolabile, making them poorly detectable via GC-MS. This explains why such classes, though indicated by FT-IR, were underrepresented in the GC-MS profile. This also illustrates the strength of a dual-platform approach: FT-IR offers class-level functional group identification, while GC-MS confirms molecular identities of thermally stable components.

Implications and future directions

While GC-MS offers a robust semi-quantitative overview of extractable volatile compounds, its limitations must be acknowledged. The detected peak areas do not reflect absolute concentrations, and many non-volatile bioactives, particularly flavonoids and glycosides, remain undetected without prior derivatization. Thus, for a complete phytochemical fingerprint, future studies should incorporate high-resolution techniques such as UPLC-MS/MS or HPLC for flavonoid and polyphenol quantification.

Furthermore, bioassay-guided fractionation, in vitro/in vivo validation, and toxicological studies are needed to establish safety, dose–response, and therapeutic mechanisms. These steps will help link compound profiles to real-world bioactivity, including antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant potential.

Conclusion

This study provides the first combined FT-IR and GC-MS phytochemical profiling of Persea americana leaves from Uganda, revealing a rich diversity of bioactive constituents influenced by solvent polarity. Both ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts contained overlapping functional groups, including phenolics, flavonoids, and esters, with subtle differences in lipophilic content. While ethanol yielded a higher extract weight, ethyl acetate revealed greater chemical diversity by GC-MS, particularly in compounds associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activity. These solvent-dependent variations underscore the importance of extraction strategy in natural product research.

These findings highlight the therapeutic promise of avocado leaves, an underutilized and accessible plant material with potential applications in managing oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic disorders. This work lays a foundation for future studies involving UPLC-MS/MS profiling, bioassay-guided isolation, and pharmacological validation, and supports the development of avocado leaf-based nutraceuticals in sustainable drug discovery.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PA-ETH:

-

Ethanolic extract of Persea americana leaves

- PA-ETHYL:

-

Ethyl acetate extract of Persea americana leaves

- GC-MS:

-

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- FT-IR:

-

Fourier transform infrared

- RT:

-

Retention time

References

Agunloye, M. O. et al. The role of avocado plant and its derivatives in the management of diabetes mellitus: A natural approach to glycemic control. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 24(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-024-01551-y (2025).

Dreher, M. L. & Davenport, A. J. Hass avocado composition and potential health effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 53(7), 738–750 (2013).

Agunloye, M. O. et al. Avocado Persea americana in diabetes management: A systematic review of preclinical evidence and its translational potential. F1000Research. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.162807.1 (2025).

Miñón-Hernández, D. et al. Avocado creole peel ameliorates metabolic alterations caused by a high sucrose fat diet in a wistar rats model. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 76, 12–19 (2021).

Brai, B. I., Odetola, A. A. & Agomo, P. U. The hypoglycemic and hypocholesterolemic potential of Persea americana leaf extracts. J. Med. Food 10(2), 356–360 (2007).

Kouamé, N. G. et al. Comparative antidiabetic activity of aqueous, ethanol, and methanol leaf extracts of Persea americana and their effectiveness in type 2 diabetic rats. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 1, 5984570. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5984570 (2019).

de Souza, A. L. et al. Chromatographic methods for separation and identification of bioactive compounds. Drug Dis. Des. Using Nat. Prod. 29, 153–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35205-8_6 (2023).

Mutha, R. E., Kalaskar, M. & Khan, Z. G. Modern analytical techniques for quality control and chemical identification of phytochemicals. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 13, 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394203680.ch09 (2025).

Dar, R. A. et al. Exploring the diverse bioactive compounds from medicinal plants: A review. J. Phytopharm. 12(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.31254/phyto.2023.12307 (2023).

Johnson, J. B. et al. The use of infrared spectroscopy for the quantification of bioactive compounds in food: A review. Molecules 28(7), 3215. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28073215 (2023).

Lima, C. R. et al. Anti-diabetic activity of extract from Persea americana mill. leaf via the activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.026 (2012).

Uysal, S. et al. Fatty acid composition, total sugar content and anti-diabetic activity of methanol and water extracts of nine different fruit tree leaves collected from Mediterranean region of Turkey. Int. J. Food Prop. 18(10), 2268–2276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2014.973964 (2015).

Abd Elkader, A. M. et al. Phytogenic compounds from avocado (Persea americana L.) extracts antioxidant activity, amylase inhibitory activity, therapeutic potential of type 2 diabetes. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29(3), 1428–1433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.11.031 (2022).

Njateng, G. S. et al. Antidiabetic potential of methanol extracts from leaves of Piper umbellatum L. and Persea americana mill. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 8(3), 160–165 (2018).

Dike, C. S. et al. GC-MS and FTIR analyses of bioactive compounds present in ethanol leaf extract of Sida acuta from Imo State Nigeria. GSCBPS 25(02), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.30574/gscbps.2023.25.2.0500 (2023).

VanderWeerd, J., Heeren, R. M. A. & Boon, J. J. Preparation methods and accessories for the infrared spectroscopic analysis of multi-layer paint. Stud. Conserv. 49, 193–210 (2004).

Francomano, F. et al. β-Caryophyllene: A sesquiterpene with countless biological properties. Appl. Sci. 9(24), 5420. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245420 (2019).

Dahham, S. S. et al. In vivo anti-inflammatory activity of β-caryophyllene, evaluated by molecular imaging. Mol. Med. Chem. https://doi.org/10.14800/mmc.1001 (2015).

Kaplan, A. & Çelikoğlu, U. Evaluation of phytochemical constituents in the whole plant parts of hexane extract of some traditional medicinal plants by GC-MS analysis. Middle East J. Sci. 6(2), 57–67 (2020).

Musa, A. M. et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of hexane leaf extract of Anisopus mannii (Asclepiadaceae). J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 4(2), 129. https://doi.org/10.5455/jice.20150106124652 (2015).

Kanimozhi, M. & Rose, C. Screening and evaluation of potential antifungal plant extracts against skin infecting fungus trichophyton rubrum. Res. Pharmacogn. https://doi.org/10.5530/pres.15.2.035 (2023).

Aldulaimi, A. K. et al. Gcms analysis and biological activities of Iraq zahdi date palm Phoenix dactylifera l volatile compositions. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 13(11), 5207–5209. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-360X.2020.00910.5 (2020).

Chen, J. Toxicity and efficacy of two emulsifiable concentrates of 2-tridecanone against red imported fire ants. Adv. Entomol. 4(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.4236/ae.2016.41006 (2015).

Hichri, A. O. et al. Study of chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Rapistrum rugosum L. essential oils from flowers, leaves, and stems. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 22(5), 1416–1426. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060X.2019.1682682 (2019).

Shaaban, M. T., Ghaly, M. F. & Fahmi, S. M. Antibacterial activities of hexadecanoic acid methyl ester and green-synthesized silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Basic Microbiol. 61(6), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.202100061 (2021).

Jalalvand, A. R. et al. Chemical characterization and antioxidant, cytotoxic, antibacterial, and antifungal properties of ethanolic extract of Allium saralicum RM fritsch leaves rich in linolenic acid, methyl ester. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. Biol. 192, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.01.017 (2019).

Kolar, M. J. et al. Linoleic acid esters of hydroxy linoleic acids are anti-inflammatory lipids found in plants and mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 294(27), 10698–10707 (2019).

Elwekeel, A. et al. Comparative gc/ms analysis, antioxidant and anticholinesterase study for the alcoholic extracts of leaves, flowers and bark of Terminalia arjuna (Roxb). Pharm. Chem. J. 58(1), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11094-024-03124-y (2024).

P Costa, J. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of phytol using non-and pre-clinical models. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 17(14), 1278–1284 (2016).

de Alencar, M. V. et al. Anticancer effects of phytol against sarcoma (S-180) and human leukemic (HL-60) cancer cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30(33), 80996–81007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28036-4 (2023).

Ghaneian, M. T. et al. Antimicrobial activity, toxicity and stability of phytol as a novel surface disinfectant. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. 2(1), 13–16 (2015).

Shabana, S. M. et al. βcaryophyllene oxide induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation of A549 lung cancer cells. Med. Oncol. 40(7), 189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-023-02022-9 (2023).

Karakaya, S. et al. A caryophyllene oxide and other potential anticholinesterase and anticancer agent in Salvia verticillata subsp. amasiaca (Freyn & Bornm.) Bornm (Lamiaceae). J. Essent. Oil Res. 326(6), 512–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2020.1813212 (2020).

Khan, I. H. & Javaid, A. Antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant components of ethyl acetate extract of quinoa stem. Plant Prot. 3(3), 125–130. https://doi.org/10.33804/pp.003.03.0150 (2019).

Abate, S. G. et al. Integrated analysis of Zehneria scabra leaf extract: Phytochemical screening, GC–MS, FT-IR spectroscopy, and antibacterial activity evaluation. Nat. Prod. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2025.2491117 (2025).

Bittencourt, M. L. et al. Metabolite profiling, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Brazilian propolis: Use of correlation and multivariate analyses to identify potential bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 76, 449–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2015.07.008 (2015).

Verma, A., Joshi, S. & Singh, D. Imidazole: Having versatile biological activities. J. Chem. 1, 329412. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/329412 (2013).

Adeyemi, M. A. et al. Phytochemical analysis and GC-MS determination of Lagenaria breviflora R. fruit. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 9(7), 1045–1050. https://doi.org/10.25258/phyto.v9i07.11178 (2017).

Bhardwaj, M. et al. Neophytadiene from Turbinaria ornata suppresses LPS-induced inflammatory response in RAW 264.7 macrophages and sprague dawley rats. Inflammation 43, 937–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-020-01179-z (2020).

Abdel-Hady, H. et al. Identification and evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Penicillium islandicum and Aspergillus tamarii ethyle acetate extracts. Pharmaceuticals. https://doi.org/10.20959/wjpps20169-7674 (2016).

Amaechi, D. et al. Phytochemical profiling (GC-MS) of the leaf extract of Mangifera indica and its hypolipidemic effect on serum lipid profile in streptozotocin-induced diabetic wistar rats. Asian Sci. Bul. 2, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.3923/asb.2024.17.23 (2024).

Firdaus, M., Kartikaningsih, H. & Sulifah, U., Sargassum spp. extract inhibits the growth of foodborne illness bacteria. In AIP Conference Proceedings Vol. 2202, no. 1 (AIP Publishing, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5141696.

Bhat, M. P. et al. Eicosane: An antifungal compound derived from streptomyces sp. KF15 exhibits inhibitory potential against major phytopathogenic fungi of crops. Environ. Res. 251, 118666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.118666 (2024).

Ayoola, A. A. et al. Phytochemicals analysis and GC-MS determination of ethanolic extracts of Azadirachta indica and Mangifera indica stem bark and their biological potentials. Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 21(1), 219–222 (2020).

Perry, P. L., Wang, Y. & Lin, J. Analysis of honeydew melon (Cucumis melo var. inodorus) flavour and GC–MS/MS identification of (E, Z)-2, 6-nonadienyl acetate. Flavour Fragr. J. 24(6), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/ffj.1947 (2009).

Narayanamoorthi, V. et al. GC MS determination of bioactive components of Peperomia pellucida (L.) Kunth. Biosci. Discov. 6(2), 83–88 (2015).

Chan, W. K. et al. Nerolidol: A sesquiterpene alcohol with multi-faceted pharmacological and biological activities. Molecules 21(5), 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21050529 (2016).

Segaran, G. R. et al. Phytochemical profiles, in vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities of Terminalia catappa. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 55(2), 51–59 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. Aroma and taste analysis of pickled tea from spontaneous and yeast-enhanced fermentation by mass spectrometry and sensory evaluation. Food Chem. 442, 138472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138472 (2024).

Fatunla, O. et al. Antibiosis and GC-MS of secondary metabolites of rhizosphere bacteria from manatee foodplants in the humic freshwater ecosystem of Eniong river Nigeria. Recent Adv. Nat. Sci. https://doi.org/10.61298/rans.2024.2.1.68 (2024).

Das, S. K. et al. In vitro α-amylase and αglucosidase inhibition, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory activity and GC-MS profiling of Avicennia alba blume. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen 23(9), 945–954 (2020).

Özer, N., Coşkuntuna, A. & Şabudak, T. Trichoderma harzianum-induced defense in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) against Plasmopara halstedii with changes in metabolite profiling of roots. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 31(12), 1403–1418. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2021.1963417 (2021).

Mahmoud, A. H. et al. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry profiling and analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and antihyperglycemic potentials of Persea americana. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 24(5), 641–649. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2021.53390.12016 (2021).

Okezu, O. P., Mamza, U. T. & Adawara, S. N. GC-MS analysis of n-hexane fruit peel extract of Persea americana (Lauraceae). Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 4(4), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.26538/tjnpr/v4i4.6 (2020).

Ajanaku, C. et al. In vitro antibacterial, phytochemical, antimycobacterial activities and GC-MS analyses of Bidenspilosa leaf extract. J. Microbiol. Biotecnol. Food Sci. 8(1), 721–725 (2018).

Noshad, M., Behbahani, B. A. & Nikfarjam, Z. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity and antioxidant activity of Citrus bergamia essential oil: Molecular docking simulations. Food Biosci. 50, 102123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2022.102123 (2022).

Manikandan, S. et al. Characterization of Commiphora caudata and its ability to combat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J. Mycopathol. Res. https://doi.org/10.57023/JMycR.61.2.2023.245 (2023).

Roy, A. C. et al. Anticancer effect of antioxidant-rich methanolic extract of Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) benth. ex kurz leaves in HepG2 and HeLa cells: A mechanistic insight. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2023.102674 (2023).

Ogunlesi, M. et al. Medicinal and pesticidal potentials of the constituents of the essential oil from Adenia cissampeloides leaves. Kem U Ind. 68, 7–21. https://doi.org/10.15255/KUI.2018.027 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Phytol increases adipocyte number and glucose tolerance through activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in mice fed high-fat and high-fructose diet. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 489(4), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.160 (2017).

An, J. Y. et al. A phytol-enriched diet activates PPAR-α in the liver and brown adipose tissue to ameliorate obesity-induced metabolic abnormalities. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 62(6), 1700688. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201700688 (2018).

Kusar, S. et al. GCMS and HPLC profiling, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Crotalaria medicaginea Lamk. S. Afr. J. Bot. 168, 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2024.03.014 (2024).

Okechukwu, P. N. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic effects of Eicosane, pentadecane, octadecane and heneicosane. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 13(4), 29–35 (2020).

Tiloke, C., Anand, K., Gengan, R. M. & Chuturgoon, A. A. Moringa oleifera and their photo nanoparticles: Potential antiproliferative agents against cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 108, 457–466 (2018).

Bagher, A. M. Intraplantar β-caryophyllene alleviates pain and inflammation in STZ-induced diabetic peripheral neuropathy via CB2 receptor activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26(9), 4430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26094430 (2025).

Klauke, A. L. et al. The cannabinoid CB2 receptor-selective phytocannabinoid beta-caryophyllene exerts analgesic effects in mouse models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 24(4), 608–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.10.008 (2014).

Dougnon, G. & Ito, M. Essential oil from the leaves of Chromolaena odorata, and sesquiterpene caryophyllene oxide induce sedative activity in mice. Pharmaceutical. 14(7), 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14070651 (2021).

Alghareeb, S. A., Alfhili, M. A. & Alsughayyir, J. Stimulation of hemolysis and eryptosis by β-caryophyllene oxide. Life 13(12), 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13122299 (2023).

Umoh, U. F. et al. GC-MS chemical profiling and anti-inflammatory effects of dichloromethane fractions from Dracaena arborea (Willd) link Asparagaceae in mice. NIJOPHASR 13(2), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.60787/nijophasr-v13-i2-559 (2024).

Zhong, R. F. et al. Identification of anti-inflammatory constituents from Kalimeris indica with UHPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS/MS and GC–MS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 165, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.034 (2015).

Oboh, G. et al. Inhibition of key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes and sodium nitroprusside induced lipid peroxidation in rats’ pancreas by phenolic extracts of avocado pear leaves and fruit. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 10(3), 208–216 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AOM contributed to conceptualization, and initial draft, AOM,OUD, OO, UNF, and OMO, contributed to writing, data analysis, data arrangement, editing, and final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Agunloye, M.O., Owu, D.U., Onaadepo, O. et al. Phytochemical characterization of ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of avocado Persea americana leaves by FT-IR and GC-MS reveals potential bioactive compounds. Sci Rep 15, 27035 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12150-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12150-z