Abstract

Optimizing solar radiation and daylighting performance is a fundamental concern in architectural design, as these factors are directly linked to enhancing building energy efficiency and environmental comfort. This study seeks to balance solar radiation and daylighting performance through architectural geometry optimization, includes building’s length, width, height, orientation, and mass distribution. Parametric modeling based on the additive and subtractive design generation algorithms included in EvoMass on the Grasshopper platform, with the goal of minimizing the solar radiation variation between summer and winter on building envelopes and maximizing useful daylight illuminance (UDI). A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm named Steady-State Island Evolutionary Algorithm (SSIEA) was applied to optimize the building geometry, ultimately yielding the Pareto front optimal solution. When compared to the reference building, the optimized design enables the building to achieve a more balanced solar radiation distribution across different seasons, resulting in a 26.89% improvement in performance. Additionally, the building’s daylighting performance is enhanced by 19.85%. The results demonstrate that leveraging the Pareto front in the early stages of building geometric form design provides architects with effective strategies and solutions for geometry optimization, enabling performance-based design decisions in subsequent stages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to carbon emissions from human activities, climate change has become a pressing global issue. The building sector is responsible for approximately 40% of global carbon emissions, with public buildings contributing to 42% of total building energy consumption1,2. Growing awareness is emerging regarding the significant impact of buildings on the climate, given their high energy consumption and carbon emissions. Solar radiation, a critical consideration in architectural design, plays a vital role in enhancing indoor comfort, human health, and energy efficiency3. However, solar radiation alone cannot address all design factors; natural daylighting is another essential element. It influences not only the comfort of indoor lighting environments but also serves as a key indicator of a building’s energy performance. Research has shown that optimal natural lighting has a positive effect on human health4.

Therefore, in sustainable building design, architects can enhance both a building’s energy performance and environmental comfort through architectural geometry optimization5,6. However, many architects tend to overlook local climate conditions and the surrounding environment in their designs7. Effective architectural geometry design can harness passive solar energy8natural daylighting9and natural ventilation7all of which contribute to improving building performance. Currently, most architects rely on experience and case studies when designing sustainable buildings. However, these approaches are inefficient in finding optimal performance solutions, thereby failing to align with the need for efficiency and extensive exploration during the early design phase10. In contrast, numerical optimization methods, which automate the iterative process of solution generation through computer programming, are more efficient in achieving optimal solutions with less time and labor during the early design phase11. Although substantial research has been conducted on passive design strategies for building envelopes and heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems12the application of numerical optimization techniques to optimize building geometry during the early design phase still holds considerable untapped potential.

Daylight, as the visible portion of solar radiation, accounts for approximately 50% of the total solar radiation. While daylight provides interior illumination, solar radiation enters the building as heat through the envelope. Controlling the balance between solar radiation and daylight directly influences both the light and thermal environments inside the building13. As a result, the building geometry has become a critical factor in architectural design, influencing aspects such as solar radiation absorption, natural daylighting, and heat transfer9. In recent years, researchers worldwide have explored building geometry optimization to enhance overall building performance14. For example, Zhu et al. optimized the daylighting and thermal load of rural buildings with three different courtyard geometries in China, achieving the optimal layout solution15. Zhang et al. investigated the geometric forms of various configurations in school buildings, using solar radiation to minimize heating and lighting energy consumption, reduce summer discomfort hours, and maximize UDI16. Wu et al. analyzed the impact of geometric parameters of building courtyards on both lighting and thermal environments. They optimized the thermal environment without compromising natural daylight conditions and determined the optimal skylight-to-courtyard ratio17. Ge et al. proposed a two-stage optimization framework for the solar energy utilization process on the roofs of large public buildings. The roof passive solar heating fraction for flat roofs, pitched roofs, and arched roofs increased by 2.8%, 111.4%, and 18.4%, respectively, while the UDI for flat roofs improved by 3.2%18. Wu et al. optimized the geometry and envelope of residential buildings in hot summer and cold winter (HSCW) regions. Compared to the baseline model, the thermal comfort index was reduced by 10.9%, while daylighting performance increased by 1.7%19. A review of the literature reveals that much of the research on building geometry optimization focuses on specific elements such as atriums, roofs, or facades, often using strategies like tilting or rotating geometries. While effective, these approaches typically result in limited variations in building geometry. Consequently, they may not be suitable for the early design phase, which requires a broader exploration of geometry variables. To ensure a more comprehensive design process, the range of architectural geometry variables should be expanded, allowing for greater flexibility and innovation during the early design stages.

When designing buildings, architects often face a trade-off between architectural design and performance optimization20. For instance, when balancing solar heat gain with indoor daylighting requirements, designers may reduce window sizes and apply coatings to minimize solar radiation, but this could negatively impact indoor lighting and views. Detailed exploration methods are typically feasible only when dealing with a limited set of design variables. However, in the early stages of architectural design, architects are confronted with an exponential increase in the number of possible variable combinations21. Consequently, when multiple variables are in conflict, it is more appropriate to identify the global Pareto optimal solution through multi-objective optimization (MOO) methods22. Once the Pareto optimal solutions are identified, architects can select the one that best aligns with both project and personal needs23. An increasing number of scholars are investigating MOO techniques to balance the various factors in architectural design. For example, Zhang et al. optimized the building geometry in China’s cold zone by focusing on three objectives: maximizing solar radiation gain, maximizing spatial efficiency, and minimizing the shape factor24. Similarly, Konis et al. optimized the geometry of office buildings across four different locations (Helsinki, New York, Mexico City, and Los Angeles), considering factors such as daylighting, passive solar energy use, and natural ventilation. The optimized designs were compared with ASHRAE 90.1 compliant reference models, confirming that energy use intensity could be reduced by 4–17%, while daylighting performance could improve by 27–65% 7. Mo et al. optimized the architectural geometry and envelope of residential buildings to better adapt to the unique climate characterized by high radiation and low temperatures. The results showed that MOO improved the building’s adaptability to this distinct climate. The optimal solution resulted in an annual thermal load of 59.12 W/m225. Jalali et al. optimized the facade of office buildings in Tehran using a genetic algorithm. The optimization enhanced usable space, reduced thermal load, and improved natural lighting within the building26. While most current research focuses on buildings in hot summer and warm winter zone, cold zone, and the mild zone, the climate conditions in HSCW zone are more complex and variable than in the other zone. In these areas, buildings may require conflicting performance characteristics across different seasons. Therefore, balancing optimization indicators for building performance to adapt to these varied climatic conditions is essential. Further research into architectural geometry optimization for HSCW zone is required.

In the process of MOO, the selection of the optimization algorithm significantly impacts both the efficiency and the outcomes of the optimization process27. The primary optimization algorithms currently in use include Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Simulated Annealing (SA), Differential Evolution (DE), and Hybrid Algorithms (HA)27,28. Among these, the GA is the most widely used, accounting for 56% of applications29. Since Schaffer first introduced MOO algorithms in the mid-1980s30they have rapidly become a research focus in various fields. For instance, Delgarm et al. used the PSO algorithm to optimize building geometry and building envelopes, improving the building’s thermal load and daylighting performance31. Junghans et al. utilized Simulated SA to improve the reliability of GA in building optimization32. Yan et al. employed a combination of GA and XGBoost to optimize thermal and lighting performance in office buildings33. Xue et al. applied the GA to optimize the natural daylighting quality of commercial buildings in cold regions, obtaining optimal design parameters through the Pareto solution set34. Howerer, applying these optimization algorithms to optimize building design in the early design phase remains challenging. Two primary issues exist: first, optimization algorithms are prone to premature convergence, which limits the diversity of results27. Second, optimization algorithms tend to be inefficient, requiring substantial time, making them unsuitable for the extensive search required in the early design phase35,36. Some researchers have combined multiple algorithms to form HA, enhancing the strengths of individual algorithms while overcoming their limitations22. For example, Vera et al. combined PSO and Hooke-Jeeves (HJ) algorithms, with the hybrid PSO/HJ algorithm demonstrating high efficiency and stability during the optimization process37. This study employs a hybrid evolutionary algorithm proposed by Wang et al., which integrates the steady-state replacement strategy with an island-based evolutionary model—collectively referred to as the Steady-State Island Evolutionary Algorithm (SSIEA)38. This algorithm is implemented within the EvoMass platform. The island model divides the overall population into multiple relatively independent subpopulations that evolve in parallel while periodically exchanging information to promote genetic diversity and avoid premature convergence. Concurrently, the steady-state replacement strategy enhances convergence efficiency by replacing only a small fraction of individuals in each generation and promptly introducing high-quality candidates into the population39. In comparison with other optimization algorithms available in the Grasshopper—such as Radial Basis Function Optimization (RBFOpt), Hypervolume-based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (HypE), Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES), and DIviding RECTangles algorithm (DIRECT)—some alternatives may outperform SSIEA in terms of either design diversity or search efficiency. Nevertheless, the core advantage of SSIEA lies in its ability to strike a robust balance between these two objectives, making it particularly well-suited for complex multi-objective design problems40. While traditional optimization algorithms are effective in identifying high-performance solutions, their application in early-stage design remains limited. Further research is needed to critically examine the selection, adaptability, and integration of optimization strategies during the initial phases of architectural design.

The building geometry significantly influences its performance during the early stages of design. However, the complex and variable climate characteristics of HSCW regions may result in negative correlations among different performance parameters, thereby complicating the task of architects in optimizing building performance. The primary objective of this study is to improve the passive sustainable performance of buildings by optimizing building geometry during the early design phase. This optimization is driven by solar radiation and daylighting data, which are derived from site-specific and climatic conditions. The goal is to refine the building geometry and orientation to maximize its environmental performance. To illustrate the effectiveness of this approach, a case study of a public building in Hangzhou, China, is presented. The primary contributions of this study are threefold. First, it utilizes the geometric form generation tool embedded in EvoMass to systematically explore building morphology under architectural constraints such as floor area and number of stories. This process identifies massing strategies suitable for performance-driven early-stage design. Unlike conventional parametric modeling tools frequently employed in previous studies—which tend to generate relatively rigid geometries—this approach better supports the exploratory demands of early design development. Second, the study implements the SSIEA, a hybrid evolutionary optimization method, to balance the competing objectives of solar radiation and daylighting in HSCW regions. This facilitates a comprehensive investigation of geometric transformation patterns and their potential for performance enhancement under MOO scenarios. While most existing studies primarily adopt GA, this research expands the algorithmic toolkit for addressing MOO challenges in architectural contexts. Finally, the study establishes a versatile simulation-based optimization workflow specifically tailored to the massing design of public buildings in HSCW climates. This framework significantly extends current research, which has predominantly focused on public buildings in exclusively hot or cold regions, by offering new insights into MOO in climatically underrepresented contexts.

Methodology

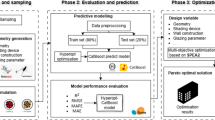

Three main steps are taken to simulate and optimize the performance of the building (Fig. 1), the first step extracts the variables of the building geometry for parametric modeling. The second step conducts performance simulation focusing on solar radiation and daylighting as two critical metrics. Finally, establishing a performance fitness function for MOO, followed by performing MOO simulation and data analysis.

Case and environmental analysis

The case study focuses on the geometry optimization process of a public building located on a university campus in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. The figure below (Fig. 2) shows the basic layout and surrounding conditions of the building. The site is an irregular trapezoid with a total area of approximately 27,500 m2. Moreover, the climatic characteristics of Hangzhou are shown in the figure below (Fig. 3). China is primarily divided into five climate zones: the severe cold zone, cold zone, HSCW zone, hot summer and warm winter zone, and temperate zone41. Hangzhou is a typical HSCW zone city (120°E, 30°N), with complex climatic variations throughout the year. These parameters are crucial for the planning, design, and construction of buildings in the region, ensuring that they can effectively adapt to the local climate conditions.

Environmental analysis, based on the environmental conditions of the above case, is the prerequisite for architectural geometry optimization and is divided into two parts. The first part includes the natural conditions of the region, such as dry bulb temperature, relative humidity, and solar radiation. Therefore, the weather file for the city of Hangzhou, where the case is located, is input into the optimization program. The second part involves the urban context, including surrounding buildings and topography, as these factors can influence the solar radiation benefits and daylighting efficiency of the target building. Based on the surrounding buildings and topography of the case site, simplified modeling was conducted as shown in Fig. 3, and these elements were integrated into the optimization program, allowing the optimized building to respond to the shadows cast by them.

Parametric modeling

EvoMass allows architects to set custom parameters based on their specific needs (Fig. 4). The first set of parameters includes basic building attributes, such as building height and number of floors, column grid dimensions, target floor area, and façade type. In the subtractive algorithm, designers can set the number and size of volumes to be removed, while in the additive algorithm, they can define the number and size of volumes to be added. These parameters determine whether the resulting building geometry will be cohesive or fragmented. In addition to the basic parameters for generating the building geometry, advanced options are also available. These include controlling volume separation, configuring the plinth level, selecting site boundaries and external volumes, as well as setting the building orientation.

The parameters of the optimized building are kept consistent with those of the reference building. The main parameters are as follows: the column grid system is 13 × 10 in the X and Y directions, with a column spacing of 8 m. The building consists of 4 to 6 floors, with a floor height of 4.4 m, a window-to-wall ratio of 0.5, and a target floor area of 25,000 m2. Additionally, the building orientation is referenced to true south, with an angular deviation range from − 15° to 15°, with a variation increment of 1°. Besides, The thermal-optical properties of building materials are applied using the default parameter values from Ladybug and Honeybee. The settings for the subtractive and additive design generation algorithms are detailed in Table 1.

Solar radiation and daylighting simulation

To ensure the accuracy and efficiency of solar radiation simulation, this study employs the Grasshopper plugin Ladybug to calculate the amount of solar radiation received (Fig. 5). Ladybug simulates daylight radiation for a specific location by extracting meteorological data from the EnergyPlus weather file. The total solar radiation incident on the test model and the radiation received at each test point on the surface are accumulated42. The accuracy of the simulation results using Ladybug has been extensively validated43,44. Since the study area is located in HSCW zone, it is inadequate to consider heat gain or heat loss in isolation; both factors must be addressed to meet climatic requirements. High-performance buildings demand lower solar radiation in the summer and higher radiation in the winter to minimize both cooling and heating loads. Therefore, the evaluation criterion for solar radiation is defined as the difference between the solar radiation received by the building surface in the summer and that in the winter. In other words, the smaller the difference, the greater the building’s adaptability to the climate. The formula is as follows45:

Where RA is the difference in solar radiation per unit area of the building envelope between summer and winter (kWh/m2); RAsummer is the solar radiation per unit area of the building envelope in the summer (kWh/m2); and RAwinter is the solar radiation per unit area of the building envelope in the winter (kWh/m2).

The Grasshopper plugins Ladybug and Honeybee are employed to conduct annual daylighting simulations (Fig. 5). To quantify and evaluate annual daylighting performance, UDI is used as the metric. UDI is defined as the percentage of time that natural daylight illuminance within a specified range is present in a work area, relative to the total working hours throughout the year. According to the lighting standards in the “Code for Lighting Design of Buildings” (GB50033-2013), the required illuminance for reading and writing in indoor spaces ranges from 300 lx to 2000 lx. Therefore, it is assumed that when UDI falls below 300 lx, indoor lighting does not meet the needs of the occupants, and additional artificial lighting is needed; when UDI exceeds 2000 lx, glare occurs, necessitating the use of artificial lighting46. In addition, the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America recommends a design illuminance of 300 lx for offices, classrooms, and libraries. Since the reference building is located within a university campus, its primary functions include offices and classrooms47. Consequently, this study uses the percentage of time that UDI falls within the 300 lx to 2000 lx range, relative to the total working hours, as the daylighting performance indicator. The point grid for evaluating UDI is positioned 0.7 m above the ground with a 5-meter spacing.

Performance fitness function and MOO simulation

After completing the building’s solar radiation and daylighting performance simulation, two performance optimization objective functions need to be defined.The optimization objectives include minimizing the difference between the summer and winter solar radiation received by the building envelope, while maximizing the annual UDI. With these two objectives, Pareto optimization is used in this case study, as it effectively avoids falling into local optima. In addition to the two building performance objectives, the total floor area of the generated building is also included as a constraint in the optimization algorithm. Any deviation from the target area will affect the building’s final fitness, while buildings with similar floor areas allow for a comparative evaluation of their performance optimization. The final fitness evaluation function for the two objectives is defined as follows:

Where RA is the difference in solar radiation per unit area of the building envelope between summer and winter (kWh/m2), RAsummer represents the solar radiation per unit area of the building envelope in the summer (kWh/m2), RAwinter represents the solar radiation per unit area of the building envelope in the winter (kWh/m2), UDI represents the Useful Daylight Illuminance (%), GFAactual represents the actual floor area of the building (m2), and GFAtarget represents the target floor area of the building (m2).

Solar radiation and daylighting serve as performance evaluation metrics, and since they have different units of measurement, it is difficult to control the optimization direction using a single objective function as in a typical single-objective optimization (SOO) problem. Therefore, data preprocessing is required. Since the solar radiation objective is to minimize the value, while the daylighting objective is to maximize it, the minimization data must first be normalized, followed by a non-dimensionalization of both metrics. The process is as follows:

If x is a large-scale attribute, such as maximizing daylighting in this study,

Where min(xj) is the minimum value of the metric, max(xj) is the maximum value of the metric, and similarly for other metrics. After standardization, the minimum value of the metric is 0 and the maximum value is 1.

If x is a small-scale attribute, such as solar radiation in this study,

After standardization, the minimum value of the metric is 0 and the maximum value is 1.

The optimization design process is implemented using the SSIEA. The building geometry parameters serve as independent variables, with the additive and subtractive design algorithms generating the geometry freely based on these parameters. The two performance fitness functions, as defined above, act as dependent variables, evaluating the performance of the generated solutions. The specific parameter settings of SSIEA provided in Table 2. Five subpopulations are set for optimization, with each subpopulation containing 15 individuals. The mutation rate is set to 0.35 in the initial stages to encourage a broader and more diverse exploration of the optimization space, and later reduced to 0.1 for a deeper exploration. The competition set size is 8, meaning that 8 design individuals are selected from the subpopulations for the next evolution step. The competition selection rate is 0.5, and the number of iterations is set to 50.

The final stage of the workflow is the MOO (Fig. 5). Various algorithms can be used to optimize building performance. In this study, we employ SSIEA to find solutions, which offers higher accuracy and more diverse optimization results compared to traditional evolutionary algorithms38. The optimization process includes weather data, form generation, performance simulation, objective functions, and optimization algorithms. In this study, the Pareto method is employed for optimization, effectively preventing convergence to local optima. The essence of Pareto optimization is the identification of the optimal frontier. Points along this frontier represent Pareto optimal solutions. All Pareto optimal solutions collectively form a scatter set, and when connected, they define the Pareto optimal frontier.

Result

Reference building

To validate the optimization results, we created a simplified model of the existing building on the site (Fig. 6). The building is a four-story, enclosed structure with a total area of approximately 25,000 m2. Inserting a central atrium is a common feature for public buildings in the HSCW climate zone in China. Independent solar radiation and daylighting simulations were conducted for the reference building. Using typical meteorological year data for Hangzhou, we evaluated the percentage of time within the 300 lx to 2000 lx range for UDI over the course of the year. The simulation results indicate that the average time during which indoor illuminance falls within the 300–2000 lx range is 51.82%. Time below 300 lx accounts for 26.18%, while time above 2000 lx is 22%.

Similarly, using the same weather file for meteorological data, we simulated the solar radiation received by the building in the summer from May 1 to August 30, calculating solar radiation from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. The reference building received 363.34 kWh/m2 of solar radiation during the summer. The winter solar radiation simulation period was from December 1 to February 28, with solar radiation also calculated from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., yielding 175.16 kWh/m2. The difference between summer and winter solar radiation is 188.18 kWh/m2.

Analysis of the pareto front

To obtain more comparable optimization results, six different optimization schemes were conducted. Initially, SOO for solar radiation and daylighting were performed, each with 25 iterations, using both additive and subtractive geometry generation methods. Subsequently, MOO for solar radiation and daylighting were carried out, each with 50 iterations, based on the same geometry generation techniques. The numerical overview of optimization provided in Table 3. The goal of this approach was to provide a clearer understanding of architectural design strategies under different performance metrics, offering more comprehensive guidance for future building geometry optimization.

The MOO results for the subtractivee and additiv algorithms are presented in Figs. 7 and 8. A total of 1,075 optimized solutions were generated by each algorithm, with an approximate computation time of 15 h. The horizontal and vertical axes represent the fitness values for daylighting and solar radiation, respectively. The overall trend in the optimization scatter plots is as follows: the generated samples tend to converge toward the maximum daylighting value, while the solar radiation toward the minimum. The red line represents the Pareto frontier, offering a more intuitive view of the optimal solutions’ trends. This indicates that the MOO method effectively balances multiple performance metrics. Upon examining the Pareto front, we found that it was not clearly observable. We summarized the factors that influenced the results. Firstly, this could be related to the parameter settings in the optimization algorithm, as the population size and the operations of selection, crossover, and mutation play a critical role in the diversity of solutions found. Secondly, the number of samples or evaluation iterations may have been insufficient. It is also possible that the geometry generation algorithm, guided by performance optimization objectives, failed to provide sufficient diversity in the building geometry. For instance, the subtractive algorithm generally adopts similar geometry strategies. If the above operations do not generate enough diversity, the algorithm may focus on specific regions and fail to explore the entire solution space, resulting in an unclear Pareto front. Based on the results, the geometries generated by the additive algorithm show better performance in solar radiation, while those generated by the subtractive algorithm generally perform better in daylighting.

Figure 9 presents a line chart that illustrates the performance improvements of samples using the subtractive algorithm. The horizontal and vertical axes represent the number of iterations and the performance ratio, respectively. Each line represents the average performance of each population at different iteration stages. It is evident that the performance metrics of most design samples steadily improve after optimization and gradually level off, demonstrating significant progress compared to the building performance at the initial optimization stage. Figure 10 shows the distribution of the optimal solutions, with the horizontal and vertical axes representing the number of iterations and the performance ratio, respectively. The line connecting the points illustrates the optimal solutions at each iteration throughout the optimization process. As the number of iterations increases, the performance of the optimal solutions steadily improves. Figure 11 provides a distribution of performance metrics based on subtractive design algorithm. The horizontal axis includes building area, UDI, summer and winter solar radiation, the penalty factor for building area, and the fitness values for solar radiation and daylighting, while the vertical axis represents performance values. The trend in changes across various performance indicators during the optimization process is clearly visible. Extensive exploration was conducted to identify the optimal solution among these performance metrics, spanning a range of nearly 70%. However, given that the actual design process is influenced by multiple factors, aside from solar radiation and daylighting efficiency, numerous other factors must also be considered.

Analysis of SOO results

After obtaining the optimization results, we compared the higher-performing outcomes with those of lower performance to summarize the morphological characteristics of different architectural geometries and to derive concrete morphological strategies for performance enhancement. The results of passive solar optimization based on the subtractive and additive algorithms are illustrated in Figs. 12 and 13. Overall, individuals generated by the additive algorithm exhibited superior performance. The top three schemes reduced solar radiation by 81.18 kWh/m2, 64.17 kWh/m2, and 63.12 kWh/m2, respectively, in comparison with the reference building, with an average reduction of 71.82 kWh/m2. This corresponds to a decrease of 43.13%, 34.10%, and 33.54%, with an average reduction of 36.92%. For the subtractive algorithm, the top three high-performance geometries achieved reductions of 52.31 kWh/m2, 47.75 kWh/m2, and 47.49 kWh/m2, with an average of 49.18 kWh/m2, corresponding to a decrease of 27.79%, 25.37%, and 25.23%, and an average reduction of 26.13%.

In regions characterized by HSCW, summer is often humid and sultry, while winter tends to be cold and damp. Accordingly, architectural design must accommodate solar shading and natural ventilation during the summer months, while ensuring effective thermal insulation in winter. Among the high-performance geometric forms generated by the subtractive algorithm, prominent features include expansive elevated floors and cantilevered volumes that extend outward from the primary mass. These strategies promote self-shading, thereby reducing thermal loads. However, the incorporation of large-scale atriums increases the building’s surface exposure to solar radiation, resulting in elevated solar gains during both summer and winter. In particular, the episodic occurrence of extremely high solar radiation in summer intensifies seasonal variations in solar exposure. This heightened seasonal fluctuation is a key factor contributing to the inferior performance of the subtractive algorithm relative to the additive one. Given the solar exposure from the east and west in HSCW climates, the building mass is rotated towards the west and east to reduce direct solar incidence. The additive algorithm similarly adopts elevated floors and cantilevered volumes, utilizing geometric articulation to enhance self-shading. This method proves to be a significant strategy for mitigating solar radiation through the manipulation of the building’s geometry. Furthermore, the additive algorithm tends to generate more compact and clustered volumes, which facilitate mutual shading among adjacent building masses and help reduce solar gain during summer. Additionally, by reducing building mass on the eastern and western façades, and through strategic projection or recession of those elements, the additive algorithm minimizes radiation on these vulnerable surfaces. The rotation of the overall building mass toward the east and west further strengthens this effect, effectively mitigating both western and eastern solar exposure. The reduction in west-facing area is compensated by newly introduced cantilevered volumes, which simultaneously serve as shading devices. Hence, the additive algorithm not only produces geometry with better average adaptability but also demonstrates more effective solar control strategies through geometric compactness and rational massing articulation.

Figures 14 and 15 present the daylighting optimization results based on subtractive and additive algorithms. The findings indicate that the subtractive algorithm’s morphological strategy yields superior average fitness. The top three optimized schemes under this approach improved daylighting performance by 16.57%, 11.56%, and 10.82%, respectively, compared to the reference building, with an average increase of 12.98%. In contrast, the top three additive-algorithm schemes reduced daylighting performance by 1.61%, 1.87%, and 3.23%, averaging a decline of 2.23%.

Hangzhou’s geographical location receives an annual average daylight illuminance of 30–35 klx, with relatively limited sunlight. To address this constraint, the subtractive algorithm employs shallow floor plates that facilitate deeper penetration of natural light into interior spaces, thereby significantly improving indoor daylighting performance. It also incorporates design strategies such as elevated floors and large-scale atriums, which reduce mutual shading between building volumes and ensure favorable daylight access for most of the day. In response to shading caused by adjacent structures, high-performing design solutions generated by the subtractive algorithm frequently adopt elevated ground floors to mitigate obstruction from foreground buildings. Conversely, the additive algorithm, constrained by its inherent generative logic, struggles to produce shallow plans or expansive atriums as effectively as the subtractive approach. Instead, it generates elongated geometry and creates atriums to increase the spacing between building volumes, thereby improving daylight conditions. However, the overall average fitness of the geometry generated by the additive algorithm is lower than that of the subtractive algorithm. Nevertheless, the additive algorithm offers greater flexibility in massing configurations. For instance, stepped terraces on rooftops serve as effective means of increasing solar access, allowing light to filter through spatial gaps between volumes. Like its subtractive counterpart, the additive algorithm also employs elevated ground floors to mitigate shading from nearby structures. Seasonal solar variation further influences the optimization of building orientation. Although south-facing facades receive more sunlight during summer, the high solar altitude angle reduces both the depth and duration of light penetration into interior spaces. In contrast, during winter, the lower solar altitude allows sunlight to penetrate deeper and remain longer within south-facing rooms. Consequently, both algorithms typically generate buildings with a south-facing orientation, which reduces sun exposure in the summer and maximizes winter daylighting utilization.

Analysis of MOO results

Figures 16 and 17 show the optimization results combining the two objectives of solar radiation and daylighting. Nine different geometries, ranked by their comprehensive performance from highest to lowest, are displayed, with the bolded-numbered geometry representing the Pareto optimal solutions. Tables 4 and 5 quantify the performance variations of the excellent results generated by the two algorithms. The top three solutions in the comprehensive ranking generated by the additive algorithm show a reduction in solar radiation of 47.17 kWh/m2, 45.73 kWh/m2, and 57.91 kWh/m2, with an average reduction of 50.27 kWh/m2, corresponding to an average decrease of 26.71%. The UDI decreased by 0.89%, 2.27%, and 4.57%, with an average decrease of 5.02%. For the solutions ranked in the comprehensive ranking by the subtractive algorithm, the solar radiation reduced by 54.43 kWh/m2, 53.62 kWh/m2, and 53.95 kWh/m2, with an average reduction of 53.00 kWh/m2, reflecting decreases of 26.89%, 28.49%, and 28.66%, respectively, with an average decrease of 28.01%. The UDI increased by 10.18%, 6.48%, and 5.57%, with an average increase of 7.41%.

The optimization results balance the performance of both objectives, integrating prior design strategies. The building geometries identified by the optimization resembles those found in SOO. In the subtractive algorithm, characteristics such as shallow floor plans and atriums emerged, which are effective methods for enhancing daylighting. However, compared to the daylight-optimized configurations from SOO, the depth of the floor plans increased, and the atrium size decreased. This change was made to balance solar radiation performance, as these two geometric features, while improving interior daylight, significantly increase the exposed surface area to solar radiation. For buildings in HSCW climates, the primary challenge is to meet the need for heat dissipation and ventilation for cooling in summer. The observed geometric adjustments clearly aim to address this constraint. Elevated ground floors and cantilevered volumes were incorporated as self-shading strategies, effectively reducing thermal loads by limiting solar exposure. However, due to the limitations of the generative logic employed in the geometric algorithm, the resulting geometries lack diverse recesses or projections that could further improve self-shading performance. Moreover, the presence of nearby buildings reduces the sunlight entering the optimized building while also casting shadows that reduce solar radiation. Therefore, compared to the extensive use of elevated floors in SOO of daylighting, these strategies was reduced in MOO, eflecting a strategic compromise between competing performance goals.

The additive algorithm also integrated geometry strategies from the SOO, including staggered building geometry, cantilevered volumes, elevated floors, and smaller west and east façades, all of which improve solar radiation performance. By utilizing geometric articulations such as projections and recesses, the additive algorithm enhances self-shading, thereby mitigating the impact of excessive solar exposure on building performance in HSCW climates. However, compared to the results from the solar radiation-only optimization, the distance between buildings significantly increased. This adjustment was necessitated by the inclusion of daylighting as a concurrent optimization objective, since overly compact massing would obstruct interior access to natural light. As a result, atriums were introduced into the design, though they were often irregular in geometry and limited in scale. This geometric compromise is the primary reason the additive algorithm underperforms the subtractive algorithm in terms of daylighting efficiency. In response to the shading from nearby buildings, the additive algorithm frequently retained the elevated floor approach as in the SOO of daylighting. This continued reliance reflects the algorithm’s limited capacity to further enhance daylighting performance under multi-objective conditions. Consequently, geometries that modestly improved daylight access were selected through a trade-off process balancing conflicting performance metrics. In terms of building orientation, the two algorithms adopted distinct strategies based on their respective optimization priorities. The subtractive algorithm oriented buildings westward or eastward to reduce solar heat gain on the most exposed façades, while the additive algorithm favored a due-south orientation to maximize daylighting potential.

Overall, the geometries generated by the two algorithms exhibit distinct advantages and limitations in addressing solar radiation and daylighting performance. The additive algorithm, characterized by its varied massing with protrusions and recesses, enables a broader range of effective self-shading strategies, offering a comparative advantage in mitigating solar radiation. Conversely, the subtractive algorithm excels in enhancing daylighting performance; its shallow floor plans and large-scale atriums substantially improve interior daylight quality. In HSCW climates, the subtractive algorithm demonstrates greater alignment with local environmental conditions by achieving a more balanced optimization of both solar radiation control and daylight access. The geometries generated by this approach also exhibit higher average fitness compared to those produced by the additive algorithm. In practice, many public buildings in HSCW regions incorporate atriums not only to enhance daylighting but also to harness wind-induced pressure differentials for natural ventilation, thereby improving the thermal environment of the internal spaces. However, if the climate shifts to a cold region, the atrium strategy of the subtractive algorithm would become less effective, as cold climates require lower surface-area-to-volume ratios to minimize heat loss. Therefore, the choice of which geometry generation algorithm to use must be adapted to local conditions. Additionally, building design is closely related to aesthetic considerations, and the geometry generated by both algorithms offer a wider range of design options.

Conclusions

This study proposes a method for optimizing solar radiation and daylighting by altering the building geometry during the early design phase. First, parametric modeling is conducted using EvoMass’s design generative algorithm, followed by building performance simulations based on two key performance metrics: solar radiation and daylighting. Finally, MOO is performed using the Pareto method and a performance fitness function to generate solutions that meet both performance and functional requirements. To demonstrate the applicability of this optimization method, a case study of a public building on a school campus in Hangzhou, China, is presented, comparing the original building with the optimized one. The study’s conclusions are as follows:

-

1.

The additive and subtractive geometry generation algorithms in EvoMass can generate a diverse range of building geometry. Additionally, by utilizing the SSIEA algorithm in EvoMass for optimization, the optimized designs are able to balance solar radiation and daylighting, achieving multi-objective equilibrium. This provides a specific workflow for engineering problems similar to early-stage architectural design.

-

2.

Considering the climatic characteristics of HSCW regions, the optimization results indicate that a moderate atrium scale, shallow floor depth, south orientation, self-shading geometry (such as cantilevers and elevated floors), and the utilization of shading generated by surrounding buildings can significantly improve the building’s solar radiation and daylighting performance. These strategies offer valuable references for passive design in similar climate regions.

-

3.

Both geometry generation algorithms perform differently depending on the specific performance goals and climate characteristics. In this study, the subtractive algorithm is more effective in improving daylighting, while the additive algorithm excels in enhancing solar radiation. Moreover, the subtractive algorithm demonstrates stronger adaptability to the HSCW climate, with superior optimization results for these performance metrics.

It should be noted that the optimization process does not include constraints related to the vegetation shading in the environment, which could result in overestimated performance in comparison to actual conditions. Additionally, factors such as building materials, window-to-wall ratio, and shading devices significantly influence solar radiation and daylighting performance, but were not incorporated into the optimization process in this study. Future work aims to integrate these influencing factors into the optimization process. Additionally, the optimization algorithm parameters, such as mutation rate, population size, and number of iterations, require further refinement to improve the diversity of generated solutions. At present, the Pareto front remains insufficiently defined, indicating potential limitations in solution variety and convergence. Lastly, due to constraints in computational resources and software capability, the current study optimized only two objectives. In contrast, real-world design scenarios typically involve a broader set of performance criteria, which may result in a divergence between the optimized forms and those required in actual architectural practice.

The MOO design workflow proposed in this study offers a valuable approach for generating building geometry that respond to the climatic characteristics of HSCW regions. However, further research is needed on other building performance optimization problems. For example, this study only considered solar radiation and daylighting as performance objectives. Many other performance objectives are worth exploring, such as indoor and outdoor thermal comfort, building energy consumption, and natural ventilation. To enhance the practical applicability of the workflow, future studies should consider its extension to a wider range of building typologies, including residential, educational, commercial, healthcare, and senior living facilities. Moreover, testing the adaptability of the workflow across diverse climatic zones will be essential for establishing robust, climate-responsive design guidelines. As the field of computer-aided architectural design continues to evolve, future research should explore the integration of real-time meteorological data and machine learning techniques to support dynamic, adaptive optimization models. Equally important is the development of architect-friendly, interactive design tools that embed the optimization process within early-stage workflows, thereby promoting the seamless application of performance-based design strategies in practice.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cabello-López, T., Carranza-García, M., Riquelme, J. C. & García-Gutiérrez, J. Forecasting solar energy production in spain: A comparison of univariate and multivariate models at the National level. Appl. Energy. 350, 121645 (2023).

2022 Research Report of China Building Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions. Architecture 02, 57–69 (2023).

Ne’Eman, E., Craddock, J. & Hopkinson, R. G. Sunlight requirements in buildings—I. Social survey. Build. Environ. 11, 217–238 (1976).

Jiang, Y., Li, N., Yongga, A. & Yan, W. Short-term effects of natural view and daylight from windows on thermal perception, health, and energy-saving potential. Build. Environ. 208, 108575 (2022).

Brown, G. Z. Sun, wind, and light. Architectural design strategies. (Wiley, 1985).

Sun, C., Han, Y. & Feng, H. Multi-objective building form optimization method based on GANN-BIM model. Next Generation Building. 2, 1 (2015).

Konis, K., Gamas, A. & Kensek, K. Passive performance and building form: an optimization framework for early-stage design support. Sol. Energy. 125, 161–179 (2016).

Kämpf, J. H. & Robinson, D. Optimisation of building form for solar energy utilisation using constrained evolutionary algorithms. Energy Build. 42, 807–814 (2010).

Evins, R. A review of computational optimisation methods applied to sustainable building design. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 22, 230–245 (2013).

Negendahl, K. Building performance simulation in the early design stage: an introduction to integrated dynamic models. Autom. Constr. 54, 39–53 (2015).

Talami, R., Wright, J. & Howard, B. Evaluating the effectiveness, reliability and efficiency of a multi-objective sequential optimization approach for Building performance design. Energy Build. 329, 115242 (2025).

Tian, Z. et al. Towards adoption of building energy simulation and optimization for passive building design: A survey and a review. Energy Build. 158, 1306–1316 (2018).

Guo, Y. & Bart, D. Optimization of design parameters for office buildings with climatic adaptability based on energy demand and thermal comfort. Sustainability 12, 3540 (2020).

Shi, X., Tian, Z., Chen, W., Si, B. & Jin, X. A review on building energy efficient design optimization rom the perspective of architects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 65, 872–884 (2016).

Zhu, L., Wang, B. & Sun, Y. Multi-objective optimization for energy consumption, daylighting and thermal comfort performance of rural tourism buildings in North China. Build. Environ. 176, 106841 (2020).

Zhang, A. et al. Optimization of thermal and daylight performance of school buildings based on a multi-objective genetic algorithm in the cold climate of China. Energy Build. 139, 371–384 (2017).

Wu, P., Zhou, J. & Li, N. Influences of atrium geometry on the lighting and thermal environments in summer: CFD simulation based on-site measurements for validation. Build. Environ. 197, 107853 (2021).

Ge, B., Fan, Z. & Liu, J. Two-stage multi-objective optimization of solar roof design for railway-station represented large-space public buildings considering thermal efficiency, carbon emissions, and daylighting. Build. Environ. 280, 113084 (2025).

Wu, C., Pan, H., Luo, Z., Liu, C. & Huang, H. Multi-objective optimization of residential building energy consumption, daylighting, and thermal comfort based on BO-XGBoost-NSGA-II. Build. Environ. 254, 111386 (2024).

Cruz, A. S., Caldas, L. R., Mendes, V. M., Mendes, J. C. & Bastos, L. E. G. Multi-objective optimization based on surrogate models for sustainable Building design: A systematic literature review. Build. Environ. 266, 112147 (2024).

Machairas, V., Tsangrassoulis, A. & Axarli, K. Algorithms for optimization of building design: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 31, 101–112 (2014).

Pan, Y. et al. Building energy simulation and its application for building performance optimization: A review of methods, tools, and case studies. Adv. Appl. Energy. 10, 100135 (2023).

Van Veldhuizen, D. A. & Lamont, G. B. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: analyzing the state-of-the-art. Evolution. Comput. 8, 125–147 (2000).

Zhang, L., Zhang, L. & Wang, Y. Shape optimization of free-form buildings based on solar radiation gain and space efficiency using a multi-objective genetic algorithm in the severe cold zones of China. Sol. Energy. 132, 38–50 (2016).

Mo, W. et al. Towards sustainable living in high radiation cold climates: A two-phase genetic algorithm approach for residential Building optimization. Build. Environ. 266, 112133 (2024).

Jalali, Z., Noorzai, E. & Heidari, S. Design and optimization of form and facade of an office building using the genetic algorithm. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 26, 128–140 (2020).

Nguyen, A. T., Reiter, S. & Rigo, P. A review on simulation-based optimization methods applied to building performance analysis. Appl. Energy. 113, 1043–1058 (2014).

Touloupaki, E. & Theodosiou, T. Performance simulation integrated in parametric 3D modeling as a method for early stage design optimization—A review. Energies. 10, 637 (2017).

Wang, Z. & Sobey, A. A comparative review between genetic algorithm use in composite optimisation and the state-of-the-art in evolutionary computation. Compos. Struct. 233, 111739 (2020).

Schaffer, J. D. Multiple Objective Optimization with Vector Evaluated Genetic Algorithms (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1985).

Delgarm, N., Sajadi, B., Kowsary, F. & Delgarm, S. Multi-objective optimization of the building energy performance: A simulation-based approach by means of particle swarm optimization (PSO). Appl. Energy. 170, 293–303 (2016).

Junghans, L. & Darde, N. Hybrid single objective genetic algorithm coupled with the simulated annealing optimization method for building optimization. Energy Build. 86, 651–662 (2015).

Yan, H., Yan, K. & Ji, G. Optimization and prediction in the early design stage of office buildings using genetic and XGBoost algorithms. Build. Environ. 218, 109081 (2022).

Xue, Y. & Liu, W. A study on parametric design method for optimization of daylight in commercial building’s atrium in cold regions. Sustainability 14, 7667 (2022).

Wang, W., Zmeureanu, R. & Rivard, H. Applying multi-objective genetic algorithms in green building design optimization. Build. Environ. 40, 1512–1525 (2005).

Zhang, J. H. Research of improved simulated annealing optimization algorithm based on the global harmony search mechanism. Adv. Mater. Res. 482, 2500–2503 (2012).

Vera, S., Uribe, D., Bustamante, W. & Molina, G. Optimization of a fixed exterior complex fenestration system considering visual comfort and energy performance criteria. Build. Environ. 113, 163–174 (2017).

Wang, L., Janssen, P. & Ji, G. Optimization-based design exploration of Building massing typologies—EvoMass and a typology-oriented computational design optimization method for early-stage performance-based building massing design. Front. Architectural Res. 13, 1400–1422 (2024).

Wang, L., Zhang, H., Liu, X. & Ji, G. Exploring the synergy of building massing and façade design through evolutionary optimization. Front. Architectural Res. 11, 761–780 (2022).

Wang, L., Janssen, P. & Ji, G. SSIEA: a hybrid evolutionary algorithm for supporting conceptual architectural design. AI EDAM. 34, 458–476 (2020).

Mao, Y. & Chen, W. On the revision of the code for design of residential buildings GBJ96-86. Sino-foreign Archit. 05, 54–55 (1996).

Freitas, S., Catita, C., Redweik, P. & Brito, M. C. Modelling solar potential in the urban environment: State-of-the-art review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 41, 915–931 (2015).

Poon, K. H., Kämpf, J. H., Tay, S. E. R., Wong, N. H. & Reindl, T. G. Parametric study of URBAN morphology on building solar energy potential in Singapore context. Urban Clim. 33, 100624 (2020).

Liao, W., Heo, Y. & Xu, S. Simplified vector-based model tailored for urban-scale prediction of solar irradiance. Sol. Energy. 183, 566–586 (2019).

Wang, L., Chen, K. W., Janssen, P. & Ji, G. Algorithmic generation of architectural massing models for Building design optimisation: parametric modelling using subtractive and additive form generation principles. CAADRIA. 2020, 385–394 (2020).

Zhao, J. The new version of standard for daylighting design of buildings GB50033 is issued and implemented. J. Lighting Eng. 24, 1–4 (2013).

Lin, X., Fan, Y., Zhang, N., Xue, P. & Luo, T. Daylighting efficacy: A new metric for solar radiation utilization and daylighting design. Sol. Energy. 293, 113456 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all our colleagues and coauthors for their very valued contributions to this work. The authors are also very appreciative of the reviewers’ comments, which helped better the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52108257); Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. LTGS24E080006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., X.L.: Conceptualization, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. G.Z., Y.Z.: Methodology, Validation, Supervision. Z.C., Z.G.: Formal analysis, Visualization. R.W., L.F.: project administration. Y.Z., B.L.: investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lou, S., Luo, X., Chen, Z. et al. Multi-objective optimization of daylighting performance and solar radiation for building geometry using a hybrid evolutionary algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 26644 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12165-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12165-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Daylighting assessment of window layouts and architectural elements in early design stages

Scientific Reports (2025)