Abstract

This study explore the dynamics of malaria transmission utilizing a novel fractional nonlinear coupled malaria model with a beta derivative, intending to expand our understanding of the complex factors that drive disease spread. By using the General Exponential Rational Function Method (GERFM), the fractional nonlinear partial differential equations are transformed into nonlinear ordinary differential equations, yielding a range of complex traveling wave solutions, including kink, anti-kink, and dark solitons. The physical behavior of these attained solutions is illustrated through detailed 2D and 3D graphs. The analysis shows key outcomes such as the occurrence of bifurcation analysis, quasi-periodic and chaotic patterns, as well as multi-stability and sensitivity within the model, underscoring the elaborate nature of malaria transmission dynamics. These findings offer new understanding into the modeling of disease spread and provide a strong structure for future research in malaria control. Finally, the study contributes to the development of more accurate predictive models with potential applications in the biomedical sciences, extending the role of fractional calculus in comprehension complex biological systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear partial differential equations (NLPDEs) are mathematical models that describe complex systems where the relationship between variables and their partial derivatives is nonlinear. Unlike linear equations, NLPDEs can involve powers, products, or nonlinear functions of unknown variables, making them more challenging to analyze and solve. NLPDEs play a vital role in modelling real-world phenomena across fields, such as fluid dynamics, heat and mass transfer, biological processes, nonlinear optics, general relativity, quantum mechanics, and financial mathematics1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Their ability to capture intricate behaviours like turbulence, wave propagation, waveguide, diffusion, and pattern formation makes them essential tools in theoretical and applied sciences11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Similarly, deep learning models, which themselves are often based on nonlinear functions, have shown great promise in the medical field, espically in the classification and estimation of complex patterns. For instance, Joshi and Singh19 developed a deep learning model for multi-class classification and proportion estimation of abnormal brain cells, a task that involves capturing complex, nonlinear relationships in data. Additionally, they explored the advancements and challenges in applying deep learning techniques to brain lesion classification using MRI, a method that, much like NLPDEs, aims to analyze and model intricate structures and behaviors within the human body20.

Recently, many efficient techniques have been applied to attained to travelling wave solution of NLPDEs. For instance, Kamruzzaman et al.21 analyze the travelling wave solutions of the (1+1)-dimensional cKdV–mKdV equation and the sinh-Gordon equation through Bernoulli Sub-ODE technique as well as the phase portrait. Islam et al.22 find the optical soliton solutions of paraxial nonlinear Schrödinger equation through modified extended auxiliary equation method. Shakeel et al.23 derived the novel soliton solution of fractional gKdV-ZK equation by utilizing \(\left( \frac{1}{G^{\prime }}\right) , \left( \frac{G^{\prime }}{G^{2}}\right)\)-expansion method and the Kudryashov method. Arafat et al.24 investigated nonlinear optical solitons in the fractional Biswas-Arshed model using the enhanced \(\left( \frac{G^{\prime }}{G^{2}}\right)\)-expansion method, revealing diverse soliton structures with practical relevance to optical fiber communications. Bentout and Djilali25 studied a nonlocal dispersal SIR epidemic model with treatment-age effects, identifying conditions for global stability and demonstrating how treatment influences the extinction or persistence of diseases in heterogeneous environments. Godey et al.26 conducted a stability analysis of the Lugiato-Lefever model for Kerr optical frequency combs, focusing on the anomalous dispersion regime. Their findings, extending prior research on normal dispersion, underscore the critical role of stability in the dynamics of solitons within optical resonators. Qiong et al.27 derived exact soliton solutions of the \((n+1)\)-dimensional generalized Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation through the generalized unified and improved F-expansion methods, highlighting their applicability in fields such as optics, fluid dynamics, and plasma physics. Kopçasız and Yaşar28 explored the modified complex Ginzburg–Landau model using an extended auxiliary equation method, producing a variety of soliton solutions and conducting sensitivity and multistability analyses relevant to optics, fluid dynamics, and quantum mechanics. Islam29 performed a bifurcation analysis and obtained diverse exact wave solutions for the nano-ionic currents equation by using generalized auxiliary and extended hyperbolic function methods, emphasizing their usefulness in nonlinear science and engineering applications. In another study, Bentout30 examined the global dynamics of an age-structured epidemic model incorporating nonlocal dispersal and distributed delays, establishing global stability through Lyapunov functions and reinforcing the theoretical analysis with numerical simulations. Kopçasız and Yaşar31 extended their investigation to two-dimensional optical solitons within the context of the fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Further contributions by Rizvi et al.32 and Hossain et al.33 expanded the scope of bifurcation analysis in optical soliton systems the former analyzing the CNLSE-BP, and the latter focusing on the Hamiltonian amplitude equation. Their findings reveal intricate connections between chaotic behavior, bifurcation structures, and soliton dynamics, highlighting the importance of sensitivity analysis in assessing the stability of these nonlinear wave solutions.

The GERFM is utilized in this study due to its capability to effectively solve nonlinear partial differential equations (NLPDEs), espicially those involving fractional derivatives, which are common in models of complex systems like malaria transmission. GERFM enables for the derivation of exact analytical solutions, incorporating traveling wave solutions such as kink, anti-kink, and dark solitons, contributing valuable part into the dynamics of the system. One of its important advantages is its flexibility in handling strong nonlinearities and fractional derivatives, making it useful to a wide range of problems. It is also simple, smooth and more direct than many other methods,presenting clear physical understandings of the solutions. However, GERFM has limitations, containg its applicability being limited to diverse types of nonlinear equations, and its complexity increases when handling with higher-dimensional or multi-variable systems. Moreover, the method effectiveness can depend on the choice of initial supposition or trial functions. Despite these limitations, GERFM remains a powerful tool for attaining exact solutions in complex, nonlinear systems.

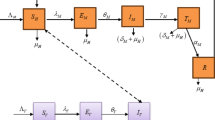

The malaria model used in this research is one of the most effective models for studying the dynamics of malaria infection. However, this model has not been fully explored through analytical techniques. In this study, we apply the General Exponential Rational Function Method (GERFM) with a fractional beta derivative. This technique is straightforward and direct, yielding various types of traveling wave solutions, including kink, anti-kink, and dark solitons. These solutions are the main novelty of the study, as they provide key insights into abrupt shifts in the transmission dynamics. Such shifts may occur due to the implementation of new control strategies, the development of medication resistance, or changes in human behavior. The application of this model has been thoroughly discussed, emphasizing how it contributes to the understanding of disease spread by utilizing a novel fractional nonlinear coupled malaria model. We also address the existing research gap, which involves the lack of accurate predictive models that capture the complex, nonlinear dynamics of malaria transmission. The primary aim of this study is to enhance our understanding of malaria dynamics and develop a more accurate predictive framework, which can be used for future research and applications in malaria control. Based on this motivation, we consider the following model34,

The fractional nonlinear coupled malaria model explore the dynamics of malaria infection, where \(M(t)\), \(X(t)\), and \(V(t)\) shows the quantities of free merozoites (malaria parasites), infected red blood cells (RBCs), and uninfected RBCs, respectively. The functions \(M = M(x, t)\), \(X = X(x, t)\), and \(V = V(x, t)\) are unknown functions, and \(\Upsilon\), \(\gamma\), \(\sigma\) are unknown parameters. The model employs fractional derivatives to explore the complex, memory-dependent dynamics of parasite growth and spread. Free merozoites \(M(t)\) infect uninfected RBCs \(V(t)\), causing to an increase in infected RBCs \(X(t)\). The evolution of each population is affected by interactions such as parasite propagation, immune response, and the natural death or extraction of infected cells. Nonlinear terms use for density-dependent growth, feedback loops, and the complex biological processes taking part in malaria transmission. The fractional derivatives reveal anomalous dynamics, such as delayed responses or long-range interactivity, which better understand the real-world complexities of malaria spread and progression.

The article is structured as follows: Beta derivative with it characteristics are listed in section 2. In section 3 we present a methodology. Section 4 for traveling wave solutions. Section 5 contains the outcome and discussion. Section 6 represents the qualitative dynamics behavior behaviour of proposed model. Section 7 provides the conclusion to this article.

Beta derivative

Let \(H_{1}(t)\) be a function defined for all non-negative t. The Beta derivative of \(H_{1}(t)\) is expressed as35

Theorem 1

If \(0 < \beta \le 1\), \(b_1, b_2 \in {\mathbb {R}}\), and \(H_1\) are different functions of order \(\beta\) with \(t > 0\).

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Methodology

The Generalized Exponential Rational Function (GERFM) is one of the main methods used to solve complex nonlinear PDEs. The main steps are given as follows36,37:

Step-1

Assume the following NPDEs,

where H(x, t) is an unknown function. To attain the nonlinear ODE, we consider the following travelling wave transformation,

When we substitute Eq. (5) into Eq. (4), then we have

Step-2

Supposed that the solution of Eq. (7) as,

The unknown values \(a_0, a_{n}\), and \(b_n\) are to be determined later. The function \(\phi (\eta )\) is defined as

Step-3 We ause the homogeneous balance technique (HBT) to the higher-order linear and nonlinear terms to get the value of \(N\) in Eq. (6).

Step-4 Putting Eq. (7) with Eq. (8) into Eq. (6), then we get the system of algebraic equations. The obtained system is solved by using Mathematica 11 software. Finally, the solution of Eq. (4) is achieved.

Complex travelling wave solutions

Consider the following complex transformation,

Putting above complex transformation into supposed malaria model (,,), then we get

Assume that the relationship between the malaria model and the inside of its victim’s body

Putting Eq. (13) into Eq. (12), then we have

Now we utilized the balancing technique on Eq. (12), then we get \(N=1\). Utilizing \(N=1\) into Eq. (7), then we have

where \(a_0, a_1\), and \(b_1\) are unknown constants to be determined. The solution of Eq. (4) is discussed as,

Case-1 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[1, -1, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[1, -1, 1, -1]\), then Eq. (8) become

When we substitute Eqs. (15) and (16) into Eq. (14), then we get a set of simple linear algebraic equations. Travelling wave solutions are obtained by solving those system of equations.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (17) with Eq. (16) into Eq. (15) to become,

The solution of Eq. (4) is given by:

where, \(\eta = x - \frac{\xi }{\beta }\left( t+\frac{1}{\Gamma (\beta )}\right) ^{\beta }\).

Set-2

Putting Eq. (20) with Eq. (16) in Eq. (15) yields,

Then solution of (4) is given as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (23) with Eq. (16) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is given by:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (26) with Eq. (16) into Eq. (15) yields,

Then solution of Eq. (4) yield as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (29) with Eq. (16) into Eq. (15) to become,

Then solution of Eq. (4) is give as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (32) with Eq. (16) into Eq. (15) yields,

Then solution of Eq. (4) is given by:

Case-2 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[i, -i, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[i, -i, i, -i]\), then Eq. (8) become as:

Equations (15) and (35) can be substituted into Eq. (14) to produce a set of basic linear algebraic equations. Solving those system of equations collectively reveals following travelling wave solutions.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (36) with Eq. (35) into Eq. (15) yields,

Then solution of Eq. (4) is given by:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (39) with Eq. (35) into Eq. (15) to become,

Then solution of Eq. (4) is given as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (42) with Eq. (35) into Eq. (15) yields,

As, solution of Eq. (4) is given below,

Set-4

Putting Eq. (45) with Eq. (35) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally solution of Eq. (4) is given below,

Set-5

Putting Eq. (48) with Eq. (35) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is given as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (51) with Eq. (35) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is given as:

Case-3 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[1+i, 1-i, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[i, -i, i, -i]\), then Eq. (8) become,

Equations (13) and (54) can be substituted into Eq. (8) to produce a set of basic linear algebraic equations. Solving those system of equations collectively reveals travelling wave solutions.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (55) with Eq. (54) into Eq. (15) yields,

The solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (58) with Eq. (54) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (61) with Eq. (54) into Eq. (15) yields,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (64) with Eq. (54) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (67) with Eq. (54) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (70) with Eq. (54) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Case-4 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[2+i, 2-i, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[i, -i, i, -i]\), then Eq. (8) become,

When Eqs. (15) and (73) are substituted into Eq. (13), a set of algebraic linear equations is achieved. The following set of travelling wave solutions can be obtained by simultaneously solving those system of equations.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (74) with Eq. (73) into Eq. (15) yields,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (77) with Eq. (73) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (80) with Eq. (73) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (83) with Eq. (73) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (86) with Eq. (73) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (89) with Eq. (73) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Case-5 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[2, 1, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[1, 0, 1, 0]\), then Eq. (8) become,

When Eqs. (15) and (92) are substituted into Eq. (13), a set of algebraic linear equations is achieved. Using those system of equations simultaneously, we can obtain the travelling wave solutions as follows:

Set-1

Putting Eq. (93) with Eq. (92) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (96) with Eq. (92) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (99) with Eq. (92) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (102) with Eq. (92) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of (4) is written as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (105) with Eq. (92) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (108) with Eq. (92) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Case-6 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[2, 0, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[-1, 0, 1, -1]\), then Eq. (8) become,

When Eqs. (45) and (111) are substituted into Eq. (13), a set of algebraic linear equations is obtained. Solving those system of equations simultaneously provides the following set of solutions for travelling waves.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (112) with Eq. (111) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (115) with Eq. (111) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (118) with Eq. (111) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (121) with Eq. (111) into Eq. (15) yields,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (124) with Eq. (111) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (127) with Eq. (111) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Case-7 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[-3, -1, -1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[-1, 1, -1, 1]\), then Eq. (8) become,

When Eqs. (15) and (130) are substituted into Eq. (13), then algebraic linear equations are acquired. We obtain the following set of solutions when those system of equations are solved simultaneously.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (131) with Eq. (130) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (134) with Eq. (130) into Eq. (15) yields,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (137) with Eq. (130) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (140) with Eq. (130) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (143) with Eq. (130) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (146) with Eq. (130) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Case-8 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[-3, -2, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[0, 1, 0, 1]\), then (8) become,

When Eqs. (53) and (149) are substituted into Eq. (13), a set of algebraic linear equations is achieved. Solving those system of equations, then we attain the following travelling wave solutions.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (150) with Eq. (149) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (153) with Eq. (149) into Eq. (15) yields,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (156) with Eq. (149) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (159) with Eq. (149) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (162) with Eq. (149) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (165) with Eq. (149) in Eq. (15) yields,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Case-9 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[-1,-2, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[1, 0, 1, 0]\), then Eq. (8) become,

When Eqs. (15) and (168) are substituted into Eq. (13), a set of algebraic linear equations is achieved. By using those equations simultaneously, we can obtain the travelling wave solutions in the following way:

Set-1

Putting Eq. (169) with Eq. (168) into Eq. (15) yields,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (172) with Eq. (168) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (175) with Eq. (168) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (178) with Eq. (168) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (181) with Eq. (168) into Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (184) with Eq. (168) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Case-10 If \(\left[ \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \sigma _3,\sigma _4 \right] =[2, 1, 1, 1]\) and \([\mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3, \mu _4]=[1, 0, 1, 0]\), then Eq. (8) become,

When Eqs. (15) and (187) are substituted into Eq. (13), a set of algebraic linear equations is achieved. The travelling wave solutions can be obtained by simultaneously solving those system of equations.

Set-1

Putting Eq. (188) with Eq. (187) in Eq. (15) to become,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-2

Putting Eq. (192) with Eq. (187) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-3

Putting Eq. (194) with Eq. (187) into Eq. (15) yields,

finally, solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-4

Putting Eq. (197) with Eq. (187) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Set-5

Putting Eq. (200) with Eq. (187) into Eq. (15) yields,

Finally, solution of Eq. (4) is proceed as:

Set-6

Putting Eq. (203) with Eq. (187) into Eq. (15) to become,

then solution of Eq. (4) is written as:

Results and discussion

The purpose of this section is to discuss the results obtained by utilizing the GERF method and the applications of the Malaria models, which are mathematical representations of the disease’s transmission and community infection. The models are used to define the dynamics of the illness and predict the effects of therapeutic interventions such as medication and insect repellent. These models can help public health experts create effective malaria control programs and make financially sound decisions about money allocation. Recently, Ali et al.34 have attained periodic, kink, dark, and bright soliton solutions with the help of \(\left( \frac{G^{\prime }}{G^{2}}\right) -\) expansion method. However, we applied the first-time GERF method to the malaria model in the current research. Then, we attained diverse types of soliton solutions, the applications of which are discussed below.

-

Figure 1 shows the dark type of soliton solutions due to localized areas of low parasite density within a population or a vector population (e.g. mosquitoes). In real-world application, this correspond to areas where strategies such as insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying, or mass drug administration have successfully suppressed transmission. The parameters \(\xi = 0.1\) and \(\gamma = 0.2\) affect the depth and width of the soliton, indicating how the strength and spatial scale of control rate affect transmission dynamics. For example, a deeper dip might represent a more effective intervention, while a broader dip could reflect a wider geographic coverage of the control strategy. The dark soliton thus yield a mathematical illustration of how localized interventions can create “cold spots” in malaria transmission, even in endemic regions.

-

Figure 2 shows the anti-kink behaviour because the phase changes in the opposite direction. Anti-kink soliton solutions simulate changes in epidemiological states or regimes in malaria modelling. Such behavior in the model sudden shifts in transmission intensity, such as the emergence of drug-resistant parasite strains, which can reverse previous gains in malaria control. On the other hand, it could show a rapid decline in cases due to a highly efficient intervention, like the introduction of a new vaccine. The parameter \(\xi = 0.1\) governs the steepness of this transition, with higher values potentially representing faster or more drastic changes. Analysis of anti-kink dynamics is important for predicting tipping points in malaria epidemiology, where small variation in control efforts or parasite genetics could lead to large-scale shifts in disease burden.

-

Figure 3 indicate the dark and kink behaviour together with different values of parameter. The dark soliton component represent pockets of low transmission due to targeted interventions, while the kink soliton reflects a sudden, large-scale transition, such as a climate-driven expansion of mosquito habitats or a policy change affecting vector control. The parameter \(\xi = 0.5\) plays an important role in modulating these effects, finding how sharply the system shifts between distinct transmission states. This dual behavior indicates the need for integrated malaria control approaches that address both localized transmission hot spots and broader environmental or societal factors affecting disease spread.

-

The kink soliton in Fig. 4 is indicating by a sudden phase shift, which could show an abrupt change in malaria transmission dynamics. Its include the fast adoption of a new intervention (e.g., widespread distribution of a new antimalarial drug) or a sudden environmental change (e.g., flooding leading to a surge in mosquito breeding sites). The parameter \(\xi = 0.1\) and the small value of \(\delta = 0.001\) show that even minor perturbations can trigger significant shifts in the system, showing the sensitivity of malaria dynamics to external factors.

Remark

The 2D plots for each figure represent how the fractional parameter \(\beta\) affect the soliton solutions. As \(\beta\) decreases, the wave profile spreads farther from the center, representing a slower, more dispersed propagation of transmission impact. In epidemiological terms, this could indicates delays in the impact of interventions due to factors like gradual immune response buildup or slow-acting vector control measures. When \(\beta = 1\), the system behaves predictably, but for \(\beta < 1\), the dynamics exhibit memory effects and anomalous diffusion, reflecting real-world complexities such as lingering immunity or spatially heterogeneous transmission. Understanding these fractional effects is important for accurately modeling malaria dynamics and optimizing the timing and scale of interventions.

Graphical view of (91) with the parameter \(\xi =0.1\) and \(\gamma =0.2\).

Graphical view of (95) with the parameter \(\xi =0.1\).

Graphical view of (133) with the parameter \(\xi =0.5\).

Graphical view of (148) with the parameter \(\xi =0.1\) and \(\delta =0.001\).

Qualitative dynamics behavior

In this part, we will explore the qualitative dynamical behavior of the system under proposed study. This will contain an analysis of bifurcations, quasi-periodic and chaotic patterns, sensitivity to initial conditions, and the phenomenon of multi-stability.

Bifurcation analysis

By applying the Galilean transformation to Eq. (14) and assuming that \(\Omega ' = V\), along with \((\gamma - \sigma ) = {\mathfrak {H}}\), we attain the following dynamical system:

To calculate the equilibrium points of the system (206), we set the system equal to zero and solve for the corresponding values \(\Omega\).

As a result, system (207) has three equilibrium points:

The Jacobian matrix for system (207) is expressed as:

We discuss the phase portraits in two different cases.

Case 1: \({\mathfrak {H}}>0\).

We take different values for the parameters, \(\gamma = 2\) and \(\sigma = 1\), which result in three equilibrium points: \((0,0)\), \((1,0)\), and \((-1,0)\). As shown in Fig. 5, \((0,0)\) is a center, and \((1,0)\) is a saddle point.

Case 2: \({\mathfrak {H}}<0\).

We take different values for the parameters, \(\gamma = 1\) and \(\sigma = 4\), which result in three equilibrium points: \((0,0)\), \((\sqrt{3} i,0)\), and \((-\sqrt{3} i,0)\). As shown in Fig. 6, \((0,0)\) is a saddle, and \((-\sqrt{3} i,0)\) is a center point.

Quasi-periodic and chaotic patterns

Quasi-periodic and chaotic patterns play an important role in investigation for the dynamics of malaria transmission models, which often used in complex interactions between the human host, mosquitoes, and environmental factors. These patterns can yield deep analysis into the spread of the disease, control strategies, and the underlying system’s long-term behavior. Applying the Galilean transformation to (14), where \(\Omega ' = V\), we attain the following dynamical system with a perturbation term:

In system 210, the parameters \(A\) and \(F\) indicates the magnitude and frequency, respectively. We investigate the behavior of quasi-periodic and chaotic patterns by varying the parameter values. Fig. 7 represents that the system exhibits quasi-periodic behavior with the parameter values \(\xi = 0.01\), \(\sigma = 5\), \(\gamma = 0.03\), \(A = 0.03\), \(F = 0.5\), and initial conditions \((0, 0.2)\). Furthermore, when keeping the other parameters fixed and varying the magnitude and frequency to \(A = 3\) and \(F = 2\), Fig. 8 shows the system’s chaotic behavior.

The 3D phase portrait presenting trajectories that follow complex, non-repetitive paths, showing two competing oscillations, relevant to the seasonal transmission cycles of malaria or changing human behavior patterns in response to disease. Figure 7b indicates cycles in the malaria dynamics such as the interaction between the biting rate of mosquitoes and the growth rate of the parasite within humans. The time series plot in Fig. 7 represents regular oscillations, indicative of seasonal changes in malaria transmission. This indicates the periodic fluctuations in the number of malaria cases over time, affected by environmental factors like temperature, rainfall, or mosquito activity.

3D phase portrait indicates an intricate, erratic path, suggesting that small changes in initial conditions (the initial number of infected individuals or mosquito population size) can lead to big different outcomes. This is important in malaria transmission models, where unpredictable fluctuations in the number of infected individuals or mosquitoes can result from seemingly small changes in factors like environmental conditions or human behavior. phase portrait indicates to a scenario in which multiple feedback loops in the malaria transmission cycle (mosquito population dynamics, human immunity, treatment rates, and intervention strategies) interact in a way that produces unpredictable and irregular dynamics. The time series plot here indicates erratic, unpredictable fluctuations in the number of malaria cases, which can be interpreted as the system entering a chaotic regime. Small changes in environmental factors, intervention strategies, or the mosquito population can cause large, unpredictable changes in malaria transmission.

Dynamics of the Lyapunov exponent (\(LE_1\), \(LE_2\), \(LE_3\)) over time for the studied system. The evolution shows that \(LE_1\) (red) starts with a high positive value before gradually stabilizing near zero, indicating initial sensitivity to perturbations with eventual convergence towards a non-divergent state. \(LE_2\) (blue) and \(LE_3\) (magenta) remain near zero and negative, respectively, confirming that the system tends toward stability without chaotic behavior. The stabilization of Lyapunov exponents over time suggests the absence of exponential divergence in the system’s trajectories as shown in Fig. 9.

Lyapunov exponent of dynamical system (211) with parametric values \(\xi =-1, \gamma=-0.02, \sigma =5, A=1, F=4\) and initial condition (0.1, 0.1, 0.1).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis quantifies the impact of input parameter uncertainty on the model’s output. This study emphasizes the importance of minor input variations by presenting results for the following parameter values: \(\xi =0.01\), \(\gamma=0.03\), \(\sigma =5\), \(A=0.03\), and \(F=0.5\). We analyze two sets of initial conditions to assess the model’s sensitivity. Figures 10 and 11 illustrate how minor adjustments in the initial conditions lead to only slight variations in system behaviour (210). A small effect reflects low sensitivity, while a significant change indicates high sensitivity. This type of sensitivity analysis is important for understanding how robust the model is to initial fluctuations in malaria transmission, and it can provide insights into how sensitive the malaria system is to intervention strategies. Initial conditions often include the number of susceptible individuals, infected individuals, and mosquitoes. A higher initial number of infected individuals (showing by the red curve) could lead to faster disease spread, while a lower initial count of infected individuals (blue curve) result in slower transmission dynamics. Consequently, we conclude that the proposed system does exhibit sensitivity, though not excessively.

Multistability

Multistability in the malaria model, as shown in Fig. 12, showing how the system can settle into different stable states depending on initial conditions, such as the number of infected individuals or mosquito population. In Fig. 12a, the phase portraits represents two different attractors, reflecting possible outcomes of malaria transmission: one with high infection levels and another with lower. Similarly, Fig. 12b indicates that different initial conditions (green and yellow) can lead to different steady states, highlighting the system’s sensitivity to early conditions. This multistability suggests that malaria can either remain endemic or be controlled based on factors like intervention techniques, mosquito density, and human immunity. Understanding this behavior is very important for designing effective malaria control programs, as interventions must be tailored to the specific initial conditions and local dynamics to push the system towards a low-prevalence state.

Conclusion

This research work makes a significant contribution to nonlinear bio-mathematics by analyzing a novel fractional nonlinear malaria model with a beta derivative. By utilizing GERF method, we attained new and complex traveling wave solutions, including kink, anti-kink, and dark solitons, which reveal key dynamics of malaria transmission. Our study highlights bifurcation behavior, quasi-periodic and chaotic patterns, as well as multi-stability and sensitivity, highlighting the complexity of disease spread. These findings provide valuable insights for future malaria control approaches and highlight the potential for applying fractional calculus to other biological systems. Our results contribute to more accurate predictive models, which can aid in understanding the factors influencing malaria transmission and intervention outcomes, offering a solid foundation for future research in both malaria modeling and epidemic dynamics.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Change history

09 November 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Acknowledgements section. The Acknowledgements section now reads: This research is funded by “Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-733), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia”. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Samad, A., Siddique, I. & Khan, Z. A. Meshfree numerical approach for some time-space dependent order partial differential equations in porous media. AIMS Math. 8, 13162–13180 (2023).

Kopçasız, B. Exploration of soliton solutions and modulation instability analysis for cold bosonic atoms in a zig-zag optical lattice in quantum physics. Nonlinear Dyn. 1–16 (2025).

Soufiane, B. & Touaoula, T. M. Global analysis of an infection age model with a class of nonlinear incidence rates. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 434(2), 1211–1239 (2016).

Rayhanul Islam, S. M., Yiasir Arafat, S. M. & Inc, M. Exploring novel optical soliton solutions for the stochastic chiral nonlinear Schrödinger equation: Stability analysis and impact of parameters. J. Nonlinear Opt. Phys. Mater. 34, 2450009 (2025).

Arafat, S. M., Saklayen, M. A. & Islam, S. M. Analyzing diverse soliton wave profiles and bifurcation analysis of the (3+1)-dimensional mKdV–ZK model via two analytical schemes. AIP Adv. 15, 1 (2025).

Golchha, N. C. & Nighojkar, A. & Nighojkar, S. A Review on the Current Strategies, Tools, and Applications. (Medinformatics, Bacterial Pangenome, 2024).

Sağlam, F. N. K., Kopçasız, B. & Tariq, K. U. Optical solitons and dynamical structures for the zig-zag optical lattices in quantum physics. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 64, 40 (2025).

Shakeel, M., Bibi, A., Chou, D. & Zafar, A. Study of optical solitons for Kudryashov’s quintuple power-law with dual form of nonlinearity using two modified techniques. Optik 273, 170364 (2023).

Shakeel, M., Bibi, A., Zafar, A. & Sohail, M. Solitary wave solutions of Camassa-Holm and Degasperis-Procesi equations with Atangana’s conformable derivative. Comput. Appl. Math. 42(2), 101 (2023).

Djilali, S., Bentout, S., Kumar, S. & Touaoula, T. M. Approximating the asymptomatic infectious cases of the COVID-19 disease in Algeria and India using a mathematical model. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 13(04), 2250028 (2022).

Djilali, S., Chen, Y. & Bentout, S. Dynamics of a delayed nonlocal reaction–diffusion heroin epidemic model in a heterogenous environment. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 48(1), 273–307 (2025).

Arafat, S. Y., Rahman, M. M., Karim, M. F. & Amin, M. R. Wave profile analysis of the (2+1)-dimensional Konopelchenko-Dubrovsky model in mathematical physics. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 8, 100573 (2023).

Sağlam, F. N. K. New analytical wave structures for the (2+1)-dimensional Chaffee-Infante equation. Univ. J. Math. Appl. 8, 41–55 (2025).

Kopçasız, B. & Yaşar, E. Inquisition of optical soliton structure and qualitative analysis for the complex-coupled Kuralay system. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2450512 (2024).

Tang, S., Feng, X., Wu, W. & Xu, H. Physics-informed neural networks combined with polynomial interpolation to solve nonlinear partial differential equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 132, 48–62 (2023).

Kopçasız, B. Qualitative analysis and optical soliton solutions galore: scrutinizing the (2+1)-dimensional complex modified Korteweg–de Vries system. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 21321–21341 (2024).

Bentout, S., Chekroun, A. & Kuniya, T. Parameter estimation and prediction for coronavirus disease outbreak 2019 (COVID-19) in Algeria. AIMS Public Health 7, 306–318 (2020).

Abdullah, Khan, N. M. & Pan, K. Advanced numerical analysis of Casson MHD nanofluid flow with bioconvection and Marangoni convection on an inclined surface. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 8, 197 (2025).

Joshi, M. & Singh, B. K. Proportion estimation and multi-class classification of abnormal brain cells. Medinformatics 1(2), 79–90 (2024).

Joshi, M. & Singh, B. K. Deep learning techniques for brain lesion classification using various MRI (from 2010 to 2022): Review and challenges. Medinformatics (2024).

Khan, K., Mudaliar, R. K. & Islam, S. M. R. Traveling waves in two distinct equations: The (1+1)-dimensional cKdV–mKdV equation and the sinh-Gordon equation. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math 9, 21 (2023).

Islam, S. M. R. et al. Some optical soliton solutions with bifurcation analysis of the paraxial nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56, 379 (2024).

Shakeel, M., Zafar, A., Alameri, A., Junaid U Rehman, M., Awrejcewicz, J., Umer, M. et al. Noval soliton solution, sensitivity and stability analysis to the fractional gKdV-ZK equation. Sci. Rep. 14, 3770 (2024).

Arafat, S. Y., Islam, S. R., Rahman, M. M. & Saklayen, M. A. On nonlinear optical solitons of fractional Biswas-Arshed Model with beta derivative. Results Phys. 48, 106426 (2023).

Bentout, S. & Djilali, S. Asymptotic profiles of a nonlocal dispersal SIR epidemic model with treat-age in a heterogeneous environment. Math. Comput. Simul. 203, 926–956 (2023).

Godey, C., Balakireva, I. V., Coillet, A. & Chembo, Y. K. Stability analysis of the spatiotemporal Lugiato-Lefever model for Kerr optical frequency combs in the anomalous and normal dispersion regimes. Phys. Rev. A 89, 063814 (2014).

Xu, Gui-Qiong. & Wazwaz, Abdul-Majid. A new (n+1)-dimensional generalized Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation: Integrability characteristics and localized solutions. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 9495–9507 (2023).

Kopçasız, B. & Yaşar, E. Soliton solutions, sensitivity analysis, and multistability analysis for the modified complex Ginzburg-Landau model. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 140, 216 (2025).

Islam, S. R. Bifurcation analysis and exact wave solutions of the nano-ionic currents equation: Via two analytical techniques. Results Phys. 58, 107536 (2024).

Bentout, S. Analysis of global behavior in an age-structured epidemic model with nonlocal dispersal and distributed delay. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 47, 7219–7242 (2024).

Kopçasız, B. & Yaşar, E. Novel exact solutions and bifurcation analysis to dual-mode nonlinear Schrödinger equation. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. (2022).

Rizvi, S. T. R. & Mustafa, B. Optical soliton and bifurcation phenomena in CNLSE-BP through the CDSPM with sensitivity analysis. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56, 393 (2024).

Hossain, M. N., Miah, M. M., Duraihem, F. Z., Rehman, S. & Ma, W. X. Chaotic behavior, bifurcations, sensitivity analysis, and novel optical soliton solutions to the Hamiltonian amplitude equation in optical physics. Phys. Scr. 99, 075231 (2024).

Ali, A., Ahmad, J. & Javed, S. Stability analysis and novel complex solutions to the malaria model utilising conformable derivatives. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138, 1–17 (2023).

Younas, T. & Ahmad, J. Dynamical analysis and soliton solutions of Kraenkel-Manna-Merle system with beta time derivative. Opt. Quantum Electron. 57, 84 (2025).

Afrin, F. U. Solitary wave solutions and investigation of the effects of different wave velocities of the nonlinear modified Zakharov-Kuznetsov model for wave propagation in nonlinear media. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 8, 100583 (2023).

Ouahid, L. Abundant soliton solutions on the fractional Kraenkel Manna Merle model (FKMM) via a new extension of the generalized exponential rational function approach (GERFA). Phys. Scr. 99, 065243 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by “Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-733), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB: Investigation, writing and editing of the original draft, formal analysis; MS: Writing and editing, reviewing, methodology, software development, investigation; SM: Reviewing, formal analysis, validation; HGA: Reviewing, formal analysis, validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdullah, Shakeel, M., Muhammad, S. et al. Complex travelling wave solutions of fractional nonlinear coupled malaria model: bifurcation, chaos, and multistability. Sci Rep 15, 30420 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12167-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12167-4